ABSTRACT

Background: The death of a child of any age can be traumatic and can leave bereaved parents experiencing negative psychological outcomes. Recent research has shown the potential utility for understanding more about the development of post-traumatic growth following bereavement.

Objective: This paper sought to identify the aspects of post-traumatic growth experienced by bereaved parents and the factors that may be involved in facilitating or preventing post-traumatic growth.

Methods: A systematic search of peer-reviewed articles with a primary focus on positive personal growth in bereaved parents was conducted. Thirteen articles met the inclusion criteria, and were analysed and synthesized according to common and divergent themes.

Results: Bereaved parents were able to experience elements of growth proposed by the post-traumatic growth model (changes in self-perception, relationships, new possibilities, appreciation of life and existential views). The papers also indicated that (1) mothers appeared to experience more growth than fathers, (2) cultural variation may impact on some participants’ experience of growth, and (3) participants were able to identify growth only once some time had passed. Potential facilitators of post-traumatic growth involved making meaning, keeping ongoing bonds with the child, being with bereaved families, and family and personal characteristics. Social networks were identified as having the potential to be either a facilitator or a barrier to growth.

Conclusions: In addition to experiencing grief, bereaved parents may experience aspects of post-traumatic growth, and a variety of factors have been identified as potential facilitators and barriers of these changes. The findings may have implications for support services (e.g. expert-by-experience services).

KEYWORDS: Personal growth, bereavement, grief, mothers, fathers, death of a child

HIGHLIGHTS: • In addition to experiencing grief, bereaved parents may experience aspects of post-traumatic growth.• Potential facilitators of post-traumatic growth involved making meaning, keeping ongoing bonds, being with bereaved families, and family and personal characteristics.• It would appear that there are gender differences in the experience of growth, with women reporting more growth than men. The process of growth takes time to occur, and cultural variation may impact on how growth is experienced.

Antecedentes: La muerte de un niño de cualquier edad puede ser traumática y provocar resultados psicológicos negativos a los padres en duelo. Investigaciones recientes han demostrado la utilidad potencial de comprender más sobre el desarrollo del crecimiento postraumático luego del duelo.

Objetivo: Este artículo buscó identificar los aspectos del crecimiento postraumático experimentados por los padres en duelo y los factores que pueden estar involucrados en facilitar o prevenir el crecimiento postraumático.

Métodos: se realizó una búsqueda sistemática de artículos revisados por pares con un enfoque principal en el crecimiento personal positivo en padres en duelo. Trece artículos cumplieron los criterios de inclusión y se analizaron y sintetizaron de acuerdo con temas comunes y divergentes.

Resultados: Los padres en duelo fueron capaces de experimentar los elementos de crecimiento propuestos por el modelo de crecimiento postraumático (cambios en la autopercepción, relaciones, nuevas posibilidades, apreciación de la vida y perspectivas existenciales). Los artículos también indicaron que (i) las madres parecían experimentar más crecimiento que los padres, (ii) la variación cultural puede afectar la experiencia de crecimiento de algunos participantes, y (iii) los participantes solo pudieron identificar el crecimiento una vez que pasó el tiempo. Los posibles facilitadores del crecimiento postraumático incluían encontrar significado, mantener lazos constantes con el niño, estar con familias en duelo y las características familiares y personales. Se identificó que las redes sociales tienen el potencial de ser tanto un facilitador como una barrera para el crecimiento.

Conclusiones: Además de experimentar dolor, los padres en duelo pueden experimentar aspectos de crecimiento postraumático, y se han identificado una variedad de factores como posibles facilitadores y barreras de estos cambios. Los hallazgos pueden tener implicaciones para los servicios de apoyo (por ejemplo, servicios de expertos por experiencia).

PALABRAS CLAVES: Crecimiento personal, pérdida, duelo, madres, padres, muerte de un niño

背景:任何年龄的儿童死亡都是创伤性的,并且可能给丧子父母带来负性的心理结果。最近的研究已表明,更好认识丧亲之后创伤后成长的发展具有潜在效用。

目的:本文旨在识别丧子父母所经历的创伤后成长的不同方面,及其可能的促进或阻碍因素。

方法:对主要关注丧亲父母的正面个人成长的同行评审文章进行系统检索, 13篇文章符合纳入标准,并根据主题相似和相异进行分析和综合。

结果:丧亲父母能够体验创伤后成长模型提出的成长要素(自我感知,关系,新可能性,感恩生活和存在主义观点的变化)。这些论文还指出,(i)母亲似乎比父亲经历更多的成长,(ii)文化差异可能影响一些被试的成长经历,(iii)参与者只有在一段时间过去才能出现成长。创伤后成长的潜在促进因素有:赋予意义,与逝世孩子保持持续的联结,与丧亲家庭一起,以及一些家庭和个人特征。社交网络有可能是促进或者阻碍成长的因素。

结论:除了悲痛之外,丧亲父母可能会经历创伤后成长的各个方面,并且识别了对成长有潜在促进和障碍作用的因素。研究结果可能对支持性服务产生影响(例如经验专家服务expert-by-experience services)。

关键词: 个人成长, 丧亲之痛, 哀伤, 母亲, 父亲, 儿童死亡

1. Background

The death of a child can lead to parents experiencing long-term negative psychological responses, such as increased depressive symptoms (Rogers, Floyd, Seltzer, & Hong, 2008), anxiety (Buchi et al., 2007), and complicated grief (Zetumer et al., 2015). Bereaved parents have also been found to experience relationship difficulties (Rogers et al., 2008) and poorer physical health (Li, Hansen, Bo Mortensen, & Olsen, 2002). In a study of bereavement outcomes, Gamino, Sewell, and Easterling (2000) highlighted that one of the factors associated with increased experiences of grief was younger age of the deceased. Even if the child is an adult at the time of the death, bereaved parents are likely to experience the death as unnatural and untimely, and are faced with the seemingly incomprehensible task of trying to find some way of continuing to live without their child (Wheeler, 2002).

Post-traumatic growth proposes that in the struggle to cope with one’s trauma, and in addition to experiencing negative outcomes, positive personal changes are possible (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). It is theorized that post-traumatic growth can manifest over five domains: self-perception, relating to others, new possibilities, appreciation of life, and existential change (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). Post-traumatic growth has been identified in many populations of individuals who have experienced a traumatic event (Helgeson, Reynolds, & Tomich, 2006). Understanding how individuals experience post-traumatic growth is important in guiding holistic support (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995).

Gamino and colleagues (2000) suggested that, in addition to understanding the many negative responses to bereavement, it is valuable to understand more about adaptive responses to death and the importance of understanding response to loss as on a continuum. Furthermore, Gamino and colleagues (2000) asserted that these more holistic understandings may provide new opportunities in therapeutic settings (e.g. being aware of possible re-framing opportunities). The notion of post-traumatic growth has been applied to bereavement research (Calhoun, Tedeschi, Cann, & Hanks, 2010); however Calhoun and colleagues (2010) are keen to emphasize that the identification of growth does not mean that distress is eliminated and, often, both experiences will co-occur. Michael and Cooper (2013) conducted a systematic review of post-traumatic growth in bereaved populations, which demonstrated that post-traumatic growth can be experienced by bereaved individuals. They identified potential mediators in the emergence of growth, which included social support, time since death, religion, and active cognitive coping strategies (Michael & Cooper, 2013). The death of a child is a unique experience which is often associated with many negative outcomes. Therefore, it is important to explore and understand post-traumatic growth in this population in the hope it may guide improved support.

1.1. Objectives

The established literature regarding the negative potential outcomes for bereaved parents in combination with emerging research for the potential utility of understanding more about post-traumatic growth in bereaved populations was the rationale for this systematic review, which set out to understand:

What aspects of post-traumatic growth are experienced by bereaved parents?

What factors appear to be associated with facilitating or preventing post-traumatic growth in bereaved parents?

What are the gaps in the current understanding of bereaved parents’ experiences of post-traumatic growth?

2. Method

2.1. Search strategy

Current literature informed the development of a protocol which guided the review. Five electronic academic databases (Web of Science, PsychARTICLES, PsychINFO, CINAL, and MEDLINE with full text) were used to retrieve articles in October 2015. A second search was conducted in July 2017 but no further articles met the criteria to be included during this search. The search terms combined ‘growth terms’ (post-traumatic growth, positive growth, benefit finding, stress related growth, positive change, PTG, adjustment, positive adaptation), ‘parent terms’ (parent*, mother*, father*) and ‘death of a child terms’ (neonatal death, bereavement, grief, loss).

2.2. Selection of articles

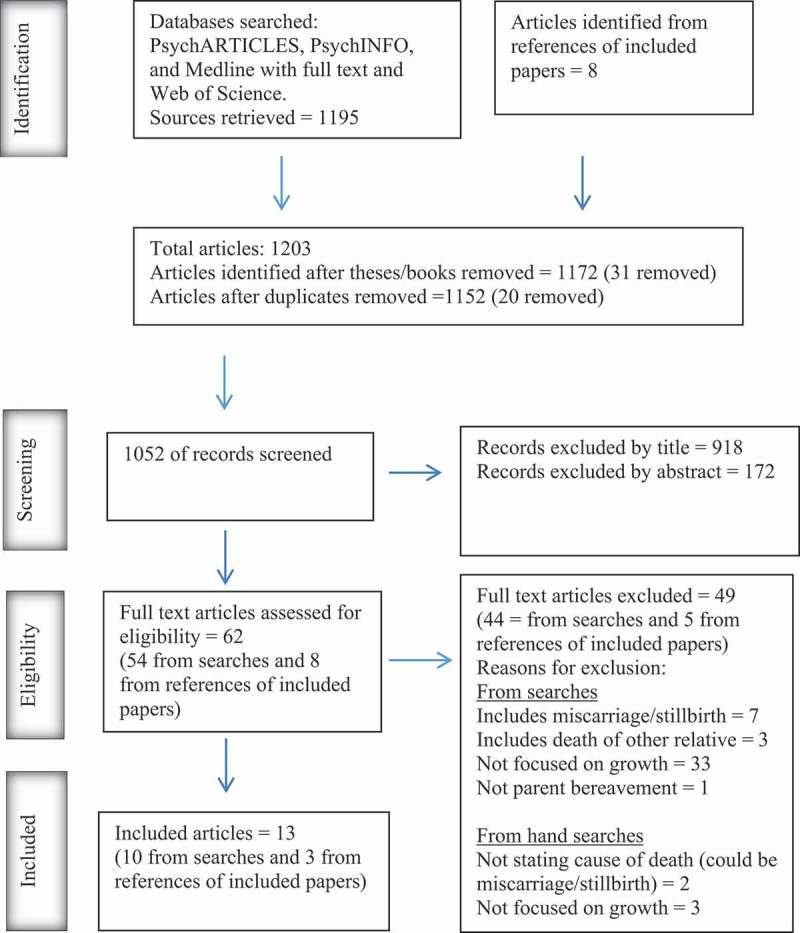

All retrieved articles were screened using the following pre-determined criteria (see Figure 1). Articles were included if they were peer reviewed (excluding theses, reviews, commentaries, conference abstracts, and books), published in English at any time, reporting primary research with a focus on parents’ experience of post-traumatic growth, positive personal change, or benefit-finding following the death of their child of any age, including adult children, from any cause of death. Articles were excluded if they included experiences of other family members (e.g. siblings), or if they included miscarriage or stillbirth. Two raters (AW and LH) independently screened all retrieved articles and subsequently discussed and agreed on articles to be included in the review; there was unanimous agreement on papers to be included.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram to illustrate identification, screening, and inclusion of articles.

2.3. Analysis

Included articles were quality assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Pluye et al., 2011; Table 1). Subsequently, a pre-determined checklist guided data extraction and facilitated the identification of common themes pertaining to the review question. Initial groupings on how papers related to aspects of post-traumatic growth were proposed by the first author and discussed with second and third authors leading to a consensus decision regarding synthesis.

Table 1.

Quality analysis.

| Screen | Qualitative | Quantitative non randomized | Quantitative descriptive | Mixed methods | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study reference | Are there clear research questions? | Do the data address the research question? | Are the sources of qualitative data relevant to address the research question? | Is the process for analysing qualitative data relevant to address the research question? | Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to the context? | Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to researchers’ influence? | Are participants recruited in a way that minimizes selection bias? | Are measurements appropriate regarding the exposure/intervention and outcomes? | In the groups being compared, are the participants comparable, or do researchers take into account the difference between these groups? | Are there complete outcome data (80% or above), and, when applicable, an acceptable response rate (60% or above), or an acceptable follow-up rate for cohort studies? | Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the quantitative research question? | Is the sample representative of the population understudy? | Are measurements appropriate? | Is there an acceptable response rate (60% or above)? | Is the mixed methods research design relevant to address the qualitative and quantitative research questions? | Is the integration of qualitative and quantitative data relevant to address the research question? | Is appropriate consideration given to the limitations associated with this integration? |

| Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster (2014) | y | y | y | y | y | n | y | y | y | y | y | y | n | ||||

| Brabant, Forsyth, and McFarlain (1997) | y | y | y | n | n | n | |||||||||||

| Buchi et al. (2007) | y | y | y | y | n/a | y | |||||||||||

| Engelkemeyer and Marwit (2008) | y | y | y | y | n/a | Information unavailable | |||||||||||

| Gerrish and Bailey (2012) | y | y | y | y | y | n | |||||||||||

| Gerrish et al. (2010) | y | y | y | y | y | n | y | n/a | y | n/a | y | y | n | ||||

| Gerrish et al. (2014) | y | y | y | y | y | n | y | n/a | y | n/a | y | y | y | ||||

| Jenewein et al. (2008) | y | y | y | y | y | y | |||||||||||

| Moore et al. (2015) | y | y | n | y | y | n | |||||||||||

| Parappully et al. (2002) | y | y | y | y | n | n | |||||||||||

| Polatinsky and Esprey (2000) | y | y | y | y | y | y | |||||||||||

| Reilly et al. (2008) | y | y | y | y | y | y | |||||||||||

| Riley et al. (2007) | y | y | y | y | n/a | Information unavailable | |||||||||||

3. Results

3.1. Overview of included papers

Thirteen articles published between July 1997 and June 2017 met the inclusion criteria; a summary of study characteristics is provided in Table 2 and a summary of the aims and findings is provided in Table 3.

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

| Authors | Type of study | Country | Ethnicity/religion | Sample | Marital status | Type of death | Age of child | Time since death | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster (2014) | Mixed methods | Austria | Not reported | 30 Female (21) Male (9) |

Married (66.7%) Divorced (13.3%) Single (6.7%) Other (13.3%) |

Illness (50%) Accident (30%) Suicide (16.7%) Homicide (3.3%) |

M = 10.2 years (years) SD = 9.4 Range = 4 days–40 years |

M = 9.73 years SD = 7.8 Range = 1–26. |

Interviews. Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI). Complicated grief module. |

| Brabant, Forsyth, and McFarlain (1997) | Qualitative | USA (USA) | Not reported | 14 Female (8) Male (6) |

Not reported | Accidents (6) Illness (3) Surgery (1) |

Range = 1–29 years Mean = 12 |

Range 1–8 years Mean = 5 years |

Interviews |

| Buchi et al. (2007) | Quantative | Switzer-land | Not reported | 54 Female (27) Male (27) |

Married (100%) | Neonatal death | Not reported | Not reported | Munich Grief Scale. PTGI. Pictorial Representation of Illness and Self-Measure (PRISM). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). |

| Engelkemeyer and Marwit (2008) | Quantative | USA | Caucasian (97%) Christian (52%) Catholic (27%) Jewish (7%) Other (14%) |

111 Gender not reported |

Married (72%) Widowed (10%) Divorced (15%) Single (3%) |

Homicide (41) Accident (35) Illness (35) |

M = 15 years SD = 7.5 |

Range = 1–372 months (months) Mean = 84.3 months SD = 89.9 months |

PTGI. World Assumptions Scale. Revised Grief Experiences Inventory. |

| Gerrish and Bailey (2012) | Case study | Not reported | Not reported | 1 Female | Married | Leukaemia | Not reported | 6 years | Biographical Grid Method (BGM). |

| Gerrish et al. (2010) | Case studies | Not reported | Caucasian (100%) | 2 Females | Married (100%) | Cancer | 9 & 22 years | 7 years & 5 years | BGM. HGRC. |

| Gerrish et al. (2014) | Mixed methods | Not reported | Caucasian (100%) | 13 Females | Married (11) Separated (1) Widowed (1) |

Cancer | Range 2–35 years M = 14.8 |

M = 4.5 years Range = 0.80–9.3 |

Interviews. BGM. Hogan Grief Reaction Checklist (HGRC). PTGI. |

| Jenewein et al. (2008) | Quantative | Switzer-land | Not reported | 92 Female (48) Male (44) |

Not reported | Neonatal death | Not reported | Not reported | HADS. PTGI. Bayley Scales of Infant Development |

| Moore et al. (2015) | Quantative | USA | Not reported | 154 Female (137) Male (17) |

Married (65.1%) Divorced (24.3%) Never married (3.3%) Widowed (3.9%) Other (3.3%) |

Death by suicide | Not reported | Not reported | PTGI. The Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R). Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Five Factor Inventory. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. Prolonged grief disorders measure. Ruminative Response Scale. Resilience scale. |

| Parappully et al. (2002) | Qualitative | USA | Caucasian (12) Hispanic (2) African American (1) Russian (1) |

16 Female (13) Male (3) |

Other (12) Divorced (4) |

Murder | Range: 7–41 years Median: 21 years |

Range = 15 months–23years Median = 6 years |

Semi-structured interviews. |

| Polatinsky and Esprey (2000) | Quantative | South Africa | Caucasian (100%) | 67 Female (49) Male (18) |

Married (73%) Divorced (13%) Single (4%) Widowed (10%) |

Motor accidents (38%) Suicide (42%) Homicide (11%) Illness (5%) Other (4%) |

Not reported | Range = 6months–8 years | Contextual information about the death. PTGI |

| Reilly et al. (2008) | Qualitative | UK | English (7) Scottish (1) Welsh (1) |

9 Female | Not reported | Illness (8) Feeding complication (1) |

Range = 23months–18 years M = 10.64 SD = 2.79 |

M = 4.2 years. Range = 10 months–10 years SD = 2.79 |

Semi-structured interviews |

| Riley et al. (2007) | Quantative | USA | Caucasian (92%) | 35 Female | Married (90%) | Accident (58%) Neonatal death (12.5%) |

M = 12 years | M = 15.7 months SD = 8.4 | LOT-R. Dispositional version of the COPE. Inventory of Social Support. HGRC with growth subscale. Inventory of Complicated Grief. PTGI. |

Table 3.

Summary of findings.

| Authors | Aims | Findings in relation to personal growth |

|---|---|---|

| Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster (2014) |

|

|

| Brabant, Forsyth, and McFarlain (1997) |

|

|

| Buchi et al. (2007) |

|

|

| Engelkemeyer and Marwit (2008) |

|

|

| Gerrish and Bailey (2012) |

|

|

| Gerrish et al. (2010) |

|

|

| Gerrish et al. (2014) |

|

|

| Jenewein et al. (2008) |

|

|

| Moore et al. (2015) |

|

|

| Parappully et al. (2002) |

|

|

| Polatinsky and Esprey (2000) |

|

|

| Reilly et al. (2008) |

|

|

| Riley et al. (2007) |

|

|

3.2. Quality appraisal

All studies utilized a cross-sectional design, which does not allow the results to be understood in terms of any developmental process of post-traumatic growth, or cause and effect of particular factors. Overall the methods were clearly described, with the exception of Brabant, Forsyth, and McFarlane’s (1997) study, which provided limited information about their method and analysis. Quantitative studies provided acceptable information regarding the reliability and validity of their chosen measures, and described rationales and procedures for data analysis. In qualitative studies, with the exception of Brabant et al. (1997), the procedures for data analysis were clearly described. However, apart from the study by Reilly, Huws, Hastings, and Vaughan (2008), qualitative papers did not comment on their consideration of researchers’ influence, either during the data collection or the analysis; this is important as biases may not be acknowledged. Three mixed methods studies were included, two of which were case studies (e.g. Gerrish & Bailey, 2012); however, further information regarding the consideration of combining these methodologies within these studies would have been helpful. Participants were typically female and reported being married, Caucasian, and from middle to high socioeconomic background, limiting the generalizability of the data.

3.3. Methods used to collect post-traumatic growth data

A variety of methods were used to collect data pertaining to post-traumatic growth as experienced by bereaved parents. Qualitative studies detailed the use of semi-structured interviews (e.g. Reilly et al., 2008).

Quantative measures predominately used the Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996), which is a 21-item Likert scale designed to assess post-traumatic growth across five domains (new possibilities, relating to others, personal strength, spiritual change, and appreciation of life). The PTGI inventory is widely used in post-traumatic growth research and has been demonstrated to show good validity and reliability (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Two studies utilized the Hogan Grief Scale (HGRC; Hogan, Greenfield, & Schmidt, 2001), which is a 61-item self-report measure consisting of six factors (despair, panic, blame and anger, detachment, disorganization, and personal growth), designed to measure the multidimensional aspects of bereavement. It has been shown to have good validity and reliability (Hogan et al., 2001).

Three studies reported the use of an alternative method, the Biographical Grid Method (BGM) (e.g. Gerrish & Bailey, 2012). Based on a social constructionist, repertory grid method, it involves participants identifying personally salient constructs defining ‘who they were’ during a variety of major life events across the lifespan. This approach was used to identify how parents’ self-constructs and overall self-narrative had been affected by their loss.

3.4. Paradox of post-traumatic growth

Despite the primary focus of the included articles being positive growth, many authors also reported parents’ experience of ongoing sadness. Reilly et al.’s (2008) participants reported many grief symptoms, including anger and despair after their child’s death. They concluded that, although the grief persisted, it became easier to manage over time. In addition to reports of growth, Buchi and colleagues (2007) highlighted that 80% of parents still showed signs of grief and 19% indicated ongoing suffering, two to six years after their premature baby had died. Gerrish and colleagues (2014) found that despite mothers being able to recognize personal growth, they also experienced enduring sadness. They reported that all of their participants demonstrated a combination of ‘complicated’ and ‘adaptive’ grief (Gerrish et al., 2014).

3.5. Grief and post-traumatic growth

Three studies identified the experience of intense grief as an important factor in the development of post-traumatic growth. Buchi et al. (2007) found a positive association between grief and growth scores, when the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores were controlled. In a hierarchical multiple regression analysis, Engelkemeyer and Marwit (2008) found that grief intensity accounted for only 4% of the variance of post-traumatic growth scores in their study. Gerrish et al. (2014) reported that women who experience high, but not overwhelming, levels of grief also experienced more growth. Additionally, Jenewein et al. (2008) found that bereaved parents had higher (but not significantly) PTGI scores overall, when compared to PTGI scores of parents whose pre-term baby had survived.

3.6. Domains of post-traumatic growth

Within the reviewed papers, all five domains of post-traumatic growth could be identified as parts of parental experiences (Calhoun et al., 2010).

3.6.1. Self-perception

In Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster’s (2014) study, personal improvement themes were the most commonly identified; participants reported ‘personal growth’, ‘being more tolerant’, and ‘developing personal potential’. All of Brabant et al.’s (1997) participants expressed a fundamental change in themselves, particularly in relation to feeling ‘more sensitive’, while Parappully and colleagues’ (2002) participants reported becoming more compassionate. Similarly, Buchi and colleagues’ (2007) participants provided the highest scoring items on the PTGI for ‘stronger than I thought I was’ and ‘knowing I can handle difficulties’. In Moore et al.’s (2015) study, parents did not score as highly on the domain on personal strength on the PTGI (19% endorsed this item), compared to other domains on the inventory. Furthermore, Gerrish and Bailey (2012) used the BGM to illustrate how a mother construed change in the self in relation to being stronger and at the same time more vulnerable, illustrating again how post-traumatic growth may coexist with psychological difficulties.

3.6.2. Changed relationships

‘Changed relationships’ was the most frequently reported theme of growth. In Brabant et al.’s (1997) study, 10 participants reported an increased desire to help others. Similarly, in a paper of higher methodological quality by Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster (2014), one-third of participants described a desire to help others, especially other bereaved individuals. In Buchi et al.’s (2007) study, high scoring factors on the PTGI for bereaved parents included ‘having compassion for others’ and ‘knowing I can count on people in times of trouble’, seemingly indicating that how parents respond to, and offer help, can change. In Jenewein et al.’s (2008) study, bereaved participants scored significantly higher on the PTGI subscale of ‘relating to others’ compared to any other domain. Similarly, 40% of Moore et al.’s (2015) participants most strongly endorsed the ‘relating to others’ subscale of the PTGI.

3.6.3. New possibilities

Buchi and colleagues (2007) documented that 78% of bereaved mothers and 44% of bereaved fathers reported discovering new priorities related to ‘what is important in life’, since the death of their baby. This theme was also identified by Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster (2014) and Brabant et al.’s (1997) participants, who reported having a reduced focus on work and financial issues, and an increased focus on family life. However, parents bereaved by suicide did not score as highly on the domain of new possibilities on the PTGI (18%), compared to other domains on the inventory (Moore et al., 2015).

3.6.4. Appreciation of life

This was one of the least frequently mentioned themes. Eleven of the 30 participants in Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster’s (2014) study reported a greater appreciation of life. In particular, participants reported having a heightened appreciation of life, living in the moment, and not taking things for granted. One of Brabant et al.’s (1997) participants reported an understanding of how precious life is. Furthermore, Moore and colleagues’ (2015) participants indicated an increased appreciation for life on the PTGI (33%).

3.6.5. Existential elements

Existential growth refers to changes in how living in the world is viewed and understood; this can encompass changes in religious views, spirituality, or meaning of life. In Moore et al.’s (2015) study, parents reported spiritual change on the PTGI (34%). Participants in Brabant et al.’s (1997) paper placed a greater emphasis on turning to religion and feeling more spiritual than before the death.

3.7. Similarities and contrasts

3.7.1. Cultural variations

Despite the studies being conducted across many countries, the samples typically reported similar demographics. The only factor that appeared to differentiate the articles in terms of demographic or cultural characteristics was religious beliefs. The studies conducted in America which explored experiences of growth found that participants discussed religion in terms of their personal growth (Brabant et al., 1997; Parappully et al., 2002). A majority (68%) of Parappully and colleagues’ (2002) participants specifically mentioned prayer and rituals as an important resource. Similarly, Brabant and colleagues’ (1997) participants discussed ‘finding God’ or ‘being more spiritual’. Conversely, studies conducted outside of America exploring the experience of growth placed very little or no emphasis on religion contributing to, or being a component of, personal growth. Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster (2014) noted that their participants did not discuss the death of their child in terms of it being ‘God’s will’; they suggested that this might be a reflection of the prevalence of religious faith in America compared with European countries. Only one study conducted outside of America mentions religion. It reported that women who already had religion in their lives, questioned, but did not change, their beliefs; women who did not have religious faith prior to the death of their child, did not turn to religion (Reilly et al., 2008).

3.7.2. Gender differences

Buchi et al. (2007) indicated that bereaved mothers in their study had higher grief scores, but also higher growth scores. Jenewein et al. (2008) reported that mothers experienced more post-traumatic growth than fathers, and that there was a significant interaction between bereavement and gender in the PTGI subscale ‘relating to others’; indicating that bereaved mothers were found to be experiencing more post-traumatic growth particularly in the area of relationships. Furthermore, some mothers reflected on how they felt they were coping differently to their husbands, which made emotion-focused activities difficult (e.g. looking at photographs) (Reilly et al., 2008). However, despite mothers demonstrating higher mean scores on four out of five of the PTGI domains, Polatinsky and Esprey (2000) suggested their study had insufficient evidence of gender differences. They suggested that, potentially, individuals who had chosen to engage in support networks may not be representative of fathers who do not chose to engage in social support networks (Polatinsky & Esprey, 2000). Similarly, some authors reported that PTGI scores (Engelkemeyer & Marwit, 2008) or reports of benefit-finding (Bogensperger & Lueger-Schuster, 2014) did not differ between mothers and fathers.

3.7.3. Time since the death

Brabant et al.’s (1997) study described how one parent reported feeling like a failure; the authors suggested that this may have been due to this individual experiencing the shortest time since the death of their child. Reilly et al. (2008) reported that mothers whose child had died more recently had greater difficulty identifying growth. Polansky and Esprey (2000) reported that time since death was significantly positively correlated with PTGI scores; in particular with factors of ‘new possibilities’ and ‘relating to others’. Moore and colleagues (2015) suggested that their participants’ scores of growth were lower than expected and proposed that this may have been due to their study including only parents bereaved within the previous two years, and that perhaps that was a barrier for them in measuring growth. Engelkemeyer and Marwit’s (2008) study found that time since death of child significantly predicted PTGI scores and accounted for 8% of the variance.

3.7.4. Nature of death

The mothers in Gerrish et al.’s (2014) study discussed how having the opportunity to prepare for their child’s death from cancer facilitated adaptation. Similarly, Polansky and Esprey (2000) reported that the mean PTGI score was higher for parents whose child died from an illness; however, their sample size was too small to determine significance. Furthermore, mothers in Reilly et al.’s (2008) study reported that some perceived positive experiences were related to the mothers’ relief that their child was no longer suffering from illness.

3.8. Facilitators and barriers of post-traumatic growth

3.8.1. Cognitive processes

Gerrish and colleagues (2010) presented two case studies which utilized the BGM. They illustrated how one woman had been able to appraise and integrate the experience of her child’s death into her overall identity, which enabled her to accept difficult events and live adaptively, e.g. seeing new possibilities. A contrasting case study featured a woman who was unable to re-narrate her assumptions of the world to integrate her child’s death and, thus, continued to experience high levels of distress.

3.8.2. Making sense of the death

Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster (2014) reported a positive relationship between meaning reconstruction and post-traumatic growth. In total, Bogensperger and Lueger-Schuster (2014) identified 20 sense-making themes, the most common of which included the purpose of the child’s life and death, and biological explanations. They reported that participants often provided multiple sense-making explanations. This was reiterated by Parappully and colleagues’ (2002) participants: 93.75% reported the importance of being able to find meaning in their child’s murder in order to facilitate growth. Parappully et al.’s (2002) participants reported that finding meaning included drawing on spirituality (e.g. belief in an afterlife) and hypothesizing worse things that might have happened.

3.8.3. Continuing bonds

All of the mothers in Gerrish et al.’s (2014) study reported continuing bonds with their children; they highlighted the importance of visiting the cemetery and speaking aloud to their child. Continuing bonds also emphasized maintaining relationships and community work (e.g. cancer awareness), drawing on the legacy of the child, which facilitated the experience of post-traumatic growth. Likewise, Parappully et al.’s (2002) participants described how continuing bonds with their child were important in their transformation and experiences of growth. Participants described many ways that bonds were continued, including focusing on their continued love for their child, having mementos (e.g. photos), and the perspective that their child would have wanted them to enjoy life again.

3.8.4. Other bereaved families

Parappully et al.’s (2002) participants described how reaching out in compassion and being able to focus their energies on supporting others, in a variety of capacities (e.g. supporting family, forming organizations), was the most common way that facilitated their healing and personal transformation. A similar finding was reported in a paper of greater methodological quality by Reilly and colleagues (2008), who found that participants gained benefit from being with other bereaved mothers, detailing that they were the only people who really understood. Additionally, all mothers in Reilly et al.’s (2008) study reported involvement with charities or services, and stated that using their experience to support others was helpful.

3.8.5. Social support

The articles demonstrated how the social environment has the potential to be supportive and facilitative of post-traumatic growth (e.g. Gerrish et al., 2014), or unhelpful for bereaved parents (e.g. Gerrish & Bailey, 2012). The mother in Gerrish and Bailey’s (2012) article highlighted how the social environment occasionally failed to respond empathetically or adequately. Mothers in Reilly et al.’s (2008) study reported developing the ability to mask their emotions when it did not feel appropriate to talk about their child, despite wanting to. Similarly, the women in Gerrish et al.’s (2014) study detailed the importance of non-judgemental listening. Additionally, in Riley et al.’s (2007) paper, perceived social support was strongly correlated with perceived personal growth. Participants in Parappully et al.’s (2002) study described a range of individuals who provided a source of social support (e.g. friends, family, clergy, or professionals).

3.8.6. Family and personal characteristics

Gerrish et al. (2014) reported that the only mother included in their study whose only child had died was also the only participant to have reported becoming suicidal and having been admitted to a psychiatric hospital. The authors proposed that having other children may be a protective factor (Gerrish et al., 2014). In Gerrish et al.’s (2010) case study, the participant described how previous difficult life events had helped her to cope with the death of her child; this was echoed by participants in Parappully et al.’s (2002) study. Moore and colleagues (2015) documented that participants who did report new possibilities were predicted by personality traits of openness to experience, neuroticism, and resilience. Similarly, Riley and colleagues (2007) reported that more personal growth was associated with dispositional factors such as active coping and support seeking.

4. Discussion

Thirteen articles were identified following the application of inclusion criteria to the search results. Post-traumatic growth is a relatively recent area of empirical study (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995) and conducting research with bereaved parents is a sensitive area; this explains the small number of articles identified. Prior to conducting the final search, scoping searches established the appropriateness of the search terms and inclusion criteria. Furthermore, the reference lists of all included papers were searched; this generates confidence that the review conclusions are based on a synthesis of all available research.

The findings indicate that bereaved parents included in these studies were able to experience aspects of post-traumatic growth in the domains of changes in self-perception, changed relationships, appreciation of life, changed priorities, and existential changes. There appeared to be gender and cultural differences in the experiences of growth. Furthermore, time since death appeared to be an important consideration associated with growth; perhaps greater time since death allowed parents the opportunity to experience more aspects of post-traumatic growth facilitators (e.g. time for sense making to occur). However, it was not possible to identify whether the nature of the death impacted on the experience of growth. Additionally, the results suggest multiple factors associated with facilitating or preventing post-traumatic growth including cognitive processes, social networks, other bereaved families, continuing bonds, making sense, and personal characteristics.

4.1. Previous literature

The findings support the proposals from Tedeschi and Calhoun (1995) that individuals need to experience distress in order to realize post-traumatic growth. However, it was not possible to establish whether extreme distress could inhibit the development of post-traumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995). Included studies identified post-traumatic growth in the domains proposed by Tedeschi and Calhoun (1995) and are consistent with a recent systematic review identifying post-traumatic growth in bereaved populations (Michael & Cooper, 2013). Furthermore, this review supports the importance of models of grief which account for adaptation (e.g. Dual Process Model of Bereavement, Stroebe & Schut, 1999; Meaning Reconstruction Model of Bereavement, Neimeyer, 2016).

These findings are consistent with the results of a recent meta-analytic study of post-traumatic growth after a variety of traumatic events (Helgeson et al., 2006), which reported that women typically perceive more benefits from a traumatic event; potentially, this is related to how women cope with the experience. The importance of time since death in relation to identifying post-traumatic growth is also potentially supported by Helgeson and colleagues (2006), who identified that benefit-finding was strongly related to less depression and greater positive affect when considering parents two years after a trauma. There is no documentation of whether the same relationship occurs at times closer to the event. Furthermore, this review supports Helgeson et al.’s (2006) findings which documented that it was not possible, based on current evidence, to draw conclusions in relation to the nature of the stressor in understanding benefit-finding. Perhaps this is because understanding how individuals make sense of the experience is more important than the event itself.

The findings are consistent with the results of a systematic review, in which meaning-making and ongoing bonds were identified as key themes in facilitating post-traumatic growth following bereavement (Michael & Cooper, 2013). The novel insights this review identifies, with regards to the experiences of bereaved parents, include the importance of being with others who have experienced the death of a child, the importance of others respecting and supporting continued bonds with the deceased child, and the potential of having other children to be a protective factor. Furthermore, the findings are consistent with literature which describes the potential for social networks to be either facilitative or disenfranchising (Doka, 1999) and a barrier to growth. A notion described by the Social Constructionist Model of Grief which posits that an individual’s experiences of grief are nested within a social context and that depending on the concordance with the individuals grief, social support can become either helpful or a hindrance (Neimeyer, Klass, & Dennis, 2014). The finding that dispositional optimism predicted growth (Reilly et al., 2008) was also found by Helgeson et al. (2006).

4.2. Evaluation of studies

All of the studies utilized cross sectional designs, therefore causal inferences about the process of post-traumatic growth cannot be made. It was encouraging to see the studies which provided comparisons with a group of parents whose baby had survived (Buchi et al., 2007; Jenewein et al., 2008).

Mothers are overrepresented in the studies and small sample sizes limited the researchers’ abilities to generalize (e.g. Jenewein et al., 2008). Additionally, although the studies were conducted worldwide, the majority of the participants were Caucasian and in the middle brackets of socioeconomic status. Furthermore, almost all of the parents in the included studies were recruited from support groups; consequently, participants are individuals who wish to discuss their experience. The question remains whether those who do not access support groups are those who experience the least post-traumatic growth (and therefore it is potentially an over-represented phenomenon), or those who experience the most post-traumatic growth and thus do not seek additional support.

4.3. Review evaluation: strengths and limitations

This review benefited from two researchers separately applying the inclusion criteria to all sources retrieved from the database searches and assessing the quality of the included papers. The review was conducted systematically; search terms and inclusion criteria were generated based on extant literature and discussion within the research team. Due to time and resource limitations, it was not possible to include papers not published in English or grey literature, which may have enhanced the review. However, a hand-search of the references of included papers provided reassurance that available studies which met the inclusion criteria were identified. The variety of approaches published within the relatively small sample of papers created some challenges with regard to comparing and contrasting the different epistemological approaches to data collection.

The findings should be viewed in the context of the limitations of the studies and the idiosyncratic experiences of bereaved parents. Every individual will vary in terms of prior mental wellbeing, social support, and subsequent potential for post-traumatic growth. Although there may be indications of growth and potential ways in which this may be facilitated or prevented, these findings cannot be generalized. However, the limited pool of studies and small samples indicate that further research would be beneficial in order to understand this phenomenon.

4.4. Clinical and research implications

Clinicians should be aware of the potential for long-lasting positive and negative changes after the death of a child (Buchi et al., 2007). These findings may help to identify parents who are at greater risk following the death of their child (e.g. limited support networks). Recognition of the value of being with other bereaved families has the potential to encourage the development of expert-by-experience services (Foot et al., 2014). Furthermore, Calhoun and colleagues (2010) discuss ‘expert companionship’; a model of working with bereaved individuals to facilitate post-traumatic growth. They describe this approach as a clinical stance which includes respect, tolerating oscillating emotions, and appreciation of the paradox.

In order to understand how post-traumatic growth occurs, a longitudinal approach would facilitate an understanding of the process of change. Recruiting from clinical settings would eliminate potential biases that may be occurring from recruiting participants from support groups. There are potential ethical dilemmas in utilizing robust research methodologies (e.g. recruiting parents at time of death). However authors have described how parents value talking about their child, even when it is painful (Dyregrov & Dyregrov, 1999), and hope that their participation will help others (Reilly et al., 2008). Furthermore, this review encourages the importance of triangulation of research methods in order to obtain results that may be generalizable, but also to capture the context and nuances of parents’ experience (Dyregrov & Dyregrov, 1999). However, future research should be cautious that changes that occur in parents’ lives after the death of a child are not merely assumed to be positive growth.

The question of whether and how gender and culture shapes experiences of post-traumatic growth is an important one. Representativeness of samples (i.e. including more fathers) and cultural differences will be important to address in future studies, particularly as this may inform how to improve support. Understanding parents’ previous mental health status would be useful (Gamino et al., 2000; Moore et al., 2015), although methodologically challenging to investigate. It was not possible to establish parental experience of post-traumatic growth with regards to parental relationships, age of the child, or the nature of the death (i.e. ‘natural’ causes such as illness versus accidents, suicide, or murder), which future research could address.

Only two articles focused on post-traumatic growth following the death of a neonatal baby and two studies included death of infants in their samples; however, these studies were primarily quantitative. Given the complex nature of post-traumatic growth and the underrepresentation in the literature of parents who have experienced a neonatal death, future research should explore the post-traumatic growth experiences in this population.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review synthesizes the existing research relating to bereaved parents’ experience of post-traumatic growth. The results indicate that in addition to experiencing distress, some bereaved parents are also able to experience positive growth resulting from the struggle with their loss. It would appear that there are gender differences in the experience of growth, with women reporting more growth than men. The review indicates that the process of growth takes time to occur, and that cultural variation – in particular religion – may impact on how growth is experienced. However, it was not possible to establish from these studies whether the nature of the death impacted on the experience of growth. The review has identified some of the factors which may facilitate the development of personal growth. These include the importance of supportive networks, continued bonds with the child, and an ability to make sense of the experience. Furthermore, personal and family characteristics may influence the experience of post-traumatic growth in both helpful and unhelpful ways. This review offers novel insights with particular relevance to bereaved parents, including the importance of being with others who have experienced the death of a child, the importance of other respecting and supporting continued bonds with the deceased child, and the potential of having other children to be a protective factor. The findings may have implications for service provision (e.g. development of expert-by-experience groups). However, included papers have limitations which reduce the generalizability of the findings. Future research would benefit from longitudinal, mixed methods research with larger and more diverse samples. Furthermore, there is a need for future research to focus upon more rigorous qualitative research, which in particular explores parental experiences of post-traumatic growth after the death of a baby.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Lyndsey Holt for independently screening all retrieved articles.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Bogensperger J., & Lueger-Schuster B. (2014). Losing a child: Finding meaning in bereavement. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5, 22910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabant S., Forsyth C., & McFarlain G. (1997). The impact of the death of a child on meaning and purpose in life. Journal of Personal & Interpersonal Loss, 2(3), 255–14. [Google Scholar]

- Buchi S., Mörgeli H., Schnyder U., Jenewein J., Hepp U., Jina E., … Sensky T. (2007). Grief and post-traumatic stress in parents 2-6 years after the death of their extremely premature baby. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 76, 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun L., Tedeschi R., Cann A., & Hanks E. (2010). Positive outcomes following bereavement: Paths to post-traumatic growth. PsychologicaBelgica, 50(1&2), 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Doka K. (1999). Disenfranchised grief. Bereavement care. 18(3), 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dyregrov A., & Dyregrov K. (1999). Long-term impact of sudden infant death: A 12-to 15- year follow up. Death Studies, 23, 635–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelkemeyer S., & Marwit S. (2008). Post-traumatic growth in bereaved parents. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(3), 344–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foot C., Gilburt H., Dunn P., Jabbal J., Seale B., Goodrich J., … Taylor J. (2014). People in control of their own health and care: The state of involvement. Retrieved fromhttp://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/people-in-control-of-their-own-health-and-care-the-state-of-involvement-november-2014.pdf

- Gamino L., Sewell K., & Easterling L. (2000). Scott and white grief study phase 2: Toward an adaptive model of grief. Death Studies, 24, 633–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish N., & Bailey S. (2012). Using the biographical grid method to explore parental grief following the death of a child. Bereavement Care, 31(1), 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish N., Neimeyer R., & Bailey S. (2014). Exploring maternal grief: A mixed-methods investigation of mothers’ responses to the death of a child from cancer. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 27(3), 151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish N., Steed L., & Neimeyer R. (2010). Meaning reconstruction in bereaved mothers: A pilot study using the biographical grid method. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 23(2), 118–142. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson V., Reynolds K., & Tomich P. (2006). A meta-analytic review of benefit-finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(5), 797–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan N., Greenfield D., & Schmidt L. (2001). Development and validation of the Hogan Grief reaction checklist. Death Studies, 25(1), 1–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenewein J., Moergeli H., Fauchere J., Bucher U., Kraemer B., Wittman L., … Buchi S. (2008). Parents’ mental health after the birth of an extremely preterm child: A comparison between bereaved and non-bereaved parents. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 29(1), 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Hansen D., Bo Mortensen P., & Olsen J. (2002). Myocardial infarction in patients who lost a child: A nationwide prospective cohort study in Denmark. American Heart Association. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000031569.45667.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael C., & Cooper M. (2013). Post-traumatic growth following bereavement: A systematic review of the literature. Counselling Psychology Review, 28(4), 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Moore M., Cerel J., & Jobes D. (2015). Fruits of trauma? Post-traumatic growth among suicide bereaved parents. Crisis, 36(4), 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer R. (2016). Meaning reconstruction in the wake of loss: Evolution of a research program. Behaviour Change, 33(2), 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer R., Klass D., & Dennis M. (2014). A social constructionist account of grief: Loss and the narration of meaning. Death Studies, 38, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parappully J., Rosenbaum R., Van Den Daele L., & Nzewi E. (2002). Thriving after trauma: The experience of parents of murdered children. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 42(1), 33–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pluye P., Robert E., Cargo M., Bartlett G., O’Cathain A., Griffiths F., ... Rousseau, M.C. (2011). Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool systematic mixed studies reviews. Retrieved fromhttp://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com

- Polatinsky S., & Esprey Y. (2000). An assessment of gender differences in the perception of benefit resulting from the loss of a child. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(4), 709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly D., Huws J., Hastings R., & Vaughan F. (2008). ‘When your child dies you don’t belong in that world any more’ – Experience of mothers whose child with an intellectual disability had died. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 21, 546–560. [Google Scholar]

- Riley L., LaMontagne L., Hepworth J., & Murphy B. (2007). Parental grief responses and personal growth following the death of a child. Death Studies, 31, 277–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C., Floyd F., Seltzer M., & Hong J. (2008). Long term effects of the death of a child on parents adjustment in midlife. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(2), 203–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., & Schut H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23, 197–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R., & Calhoun L. (1995). Transformation and trauma: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. London: Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R., & Calhoun L. (1996). The post-traumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R., & Calhoun L. (2004). Post-traumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler I. (2002). Parental bereavement: The crisis of meaning. Death Studies, 25, 51–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetumer S., Young I., Shear M., Skritskaya N., Lebowitz B., Simon N., & Zisook S. (2015). The impact of losing a child on the clinical presentation of complicated grief. Journal of Affective Disorders, 170, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]