Abstract

Background: Patients with decompensated cirrhosis (DC) and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have a high symptom burden and mortality and may benefit from palliative care (PC) and hospice interventions.

Objective: Our aim was to search published literature to determine the impact of PC and hospice interventions for patients with DC/HCC.

Methods: We searched electronic databases for adults with DC/HCC who received PC, using a rapid review methodology. Data were extracted for study design, participant and intervention characteristics, and three main groups of outcomes: healthcare resource utilization (HRU), end-of-life care (EOLC), and patient-reported outcomes.

Results: Of 2466 results, eight were included in final results. There were six retrospective cohort studies, one prospective cohort, and one quality improvement study. Five of eight studies had a high risk of bias and seven studied patients with HCC. A majority found a reduction in HRU (total cost of hospitalization, number of emergency department visits, hospital, and critical care admissions). Some studies found an impact on EOLC, including location of death (less likely to die in the hospital) and resuscitation (less likely to have resuscitation). One study evaluated survival and found hospice had no impact and another showed improvement of symptom burden.

Conclusion: Studies included suggest that PC and hospice interventions in patients with DC/HCC reduce HRU, impact EOLC, and improve symptoms. Given the few number of studies, heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes, and high risk of bias, further high-quality research is needed on PC and hospice interventions with a greater focus on DC.

Keywords: : cirrhosis, liver disease, palliative care, rapid review, symptoms, utilization

Introduction

In the United States, over 600,000 patients have cirrhosis, and it is one of the leading causes of death in the United States in adults older than the age of 25 years.1,2 There is also a growing population of persons with chronic liver disease, especially with the rise in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and Hepatitis C infection. Liver transplantation is the only cure for cirrhosis once complications of liver disease have developed; 6000–7000 transplants are performed annually in the United States based on the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network data.3 In addition, the number of patients delisted from the transplant list nearly doubled from 2009 to 2011,4 leaving a large proportion of patients with progressive liver disease who continue to suffer without the opportunity for a cure.

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis (DC) with ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, jaundice, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are in the final stages of disease, termed end-stage liver disease (ESLD), with a 1-year survival of ∼50%.5 These patients have the greatest palliative care (PC) needs for symptom management and advanced care planning for end-of-life care (EOLC).6–13

Early, concurrent involvement of PC versus usual care in chronic illnesses has been shown to lead to a better quality of life (QOL) and overall patient satisfaction.14 In other diseases like cancer and heart failure, PC has been shown to improve symptoms, EOLC, and healthcare resource utilization (HRU).15–18 To our knowledge, there are no published systematic or rapid reviews of PC interventions in DC and HCC and their impact on outcomes. Our aim in this study was to search published literature for PC interventions in DC and HCC and their impact on HRU, EOLC, and patient-reported outcomes (PRO) and synthesize the results. Given the dearth of evidence in application of PC in DC/HCC and to conduct this review in a time-efficient manner, we utilized a rapid review methodology.

Methods

Rapid review methodology

A rapid review of literature was completed over a 5-month period in 2017. Rapid reviews are used to streamline systematic review methods to synthesize evidence in a short timeframe, especially in topics that are understudied. Similar to a systematic review, it consists of a structured methodology to search literature, extract and synthesize data, and assess risk of bias, but the degree of comprehensiveness for each step can vary.19,20 Our approach was comprehensive and only differs from a systematic review in not having each step conducted by two independent reviewers to expedite the timeframe. Our review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42017054763), an international registry of systematic reviews before search.

Literature search strategy

Relevant publications in English were located through a search of literature from January 3rd to 9th, 2017 and subsequent weekly autosearches on PubMed. To address our research question of PC and hospice interventions in DC/HCC, a combination of database-specific subject headings and keywords was used in the search strategies (Table 1), covering the concepts of PC in DC and HCC. No date limits were applied. Specific study types (systematic reviews, clinical trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, and case reports) were incorporated into the search strategies for PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO. Gray literature was also searched in the database Clinicaltrials.gov. Exact search strategies used for each database are available upon request.

Table 1.

General Search Terms

| “palliative care” [subject term] OR “hospice care” [subject term] OR “terminally ill” [subject term] OR “palliat*” OR “hospice” OR “terminal*” [keywords] AND end-stage liver disease (“liver disease” [subject term] OR “liver failure” [subject term] OR “liver” [keywords] OR “hepatic” [keywords] AND “end-stage” [keywords] OR “cirrhosis” [keywords] OR “hemorrhage*” [keywords] OR “failure” [keywords] OR “portal hypertension” [keywords] OR “insufficiency” [keywords] OR “jaundice” [keywords]). |

| “palliative care” [subject term] OR “hospice care” [subject term] OR “terminally ill” [subject term] OR “palliat*” OR “hospice” OR “terminal*” [keywords] AND “hepatocellular carcinoma” [subject term] OR “hepatocellular carcinoma*” [keywords] OR “hepatocarcinoma*” [keywords] OR “liver carcinoma*” [keywords] OR “liver cell cancer” [keywords] OR “liver cell carcinoma*” [keywords] OR “hepatoma*” [keywords] |

Study selection

Two reviewers (S.K.M. and N.A.H.) divided the initial search results for screening (S.K.M.—Embase, Clinicaltrials.gov, N.A.H.—PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane). We screened results by reviewing titles and abstracts while applying inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 2). The decision to include HCC was made during the screening process because it commonly occurs in the setting of cirrhosis and has a similar or worse trajectory and symptom burden. Since this decision was made after the initial search findings, we repeated the search, including terminology for HCC (Table 1). One author (S.K.M.) screened the HCC search results. After initial searches were completed, weekly autosearches continued for PubMed.

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Study type: Systematic reviews, clinical trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, quality improvement studies | Interventions: Pharmacological (chemotherapy) or procedural (radiation, surgery, ablation, embolization) |

| Population: Decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma | Population: Metastatic disease with liver involvement, systemic diseases with hepatic involvement due to the variations in pathophysiology, disease trajectory, and symptom burden |

| Dates: No date limits applied | Comparator: If no comparator group in study |

| Interventions: Studies with palliative care or hospice intervention (what would typically be provided by a specialty palliative care provider or hospice team, such as communication regarding patient values, prognosis, understanding of disease process, in combination with symptom management and EOLC with multidisciplinary support) | Outcomes: Receipt of palliative care or hospice |

| Comparator: Usual or routine care | |

| Outcomes: HRU, EOLC, PRO | |

| Language: Published in English |

HRU, healthcare resource utilization; EOLC, end-of-life care; PRO, patient-reported outcomes.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (S.K.M., C.E.B.) extracted data independently for study design, population, and liver disease participants, intervention, comparison group, and outcomes of interest. Our main outcomes of interest included HRU, EOLC, PRO, and survival. HRU included emergency department (ED) visits, hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, hospital and ICU lengths of stay (LOS), and total cost of hospitalization. EOLC outcomes included presence of advanced directives, goals of care conversations, concordance of care with expressed wishes, resuscitation status, and location of death (home, hospital, etc.). PRO include symptoms, QOL, and patient satisfaction.

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (S.K.M., C.E.B.) performed risk of bias assessment independently and discrepancies were discussed as a team (S.K.M., C.E.B., and A.D.M.). We used the National Institutes of Health (NIH) risk of bias assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.21 Key components of the tool include assessment of internal validity with respect to study population, exposures, and outcomes, risks of selection, information and measurement biases, confounding and measures taken to address this, and appropriateness of statistical analysis. For quality improvement (QI) studies, we used the QI study minimum quality criteria with the following domains; Organizational Motivation, Intervention Rationale, Intervention Description, Organizational Characteristics, Implementation, Study Design, Comparator Description, Data Sources, Timing, Adherence/Fidelity, Health Outcomes, Organizational Readiness, Penetration/Reach, Sustainability, Spread, and Limitations.22 Each article's risk of bias assessment is available upon request.

Results

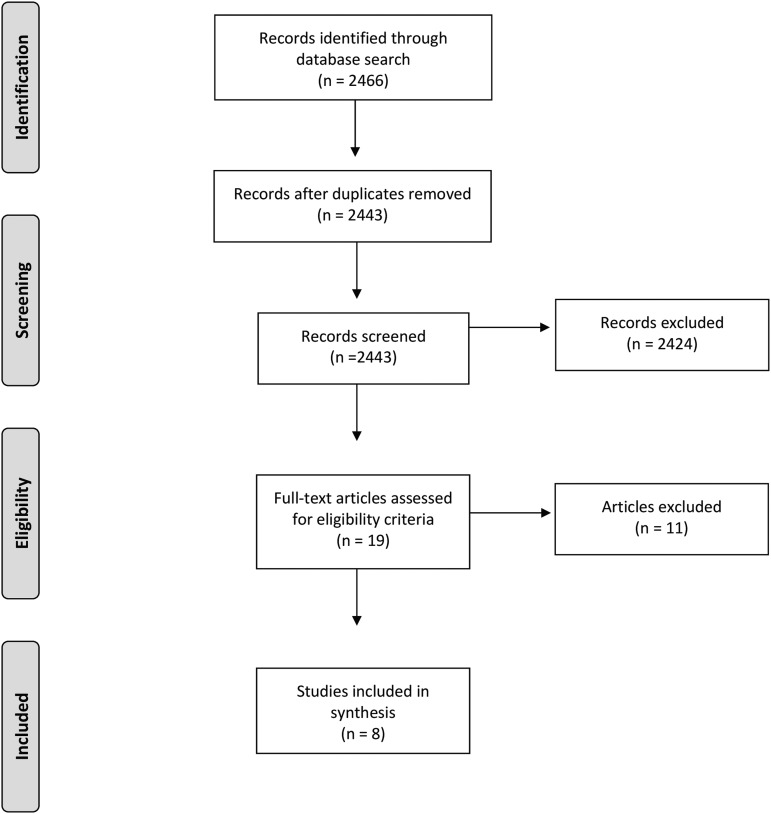

We identified a total of 2466 articles using our search strategy. After removing duplicates (23), from the remaining 2443 citations, we selected 19 for full-text screening and identified 8 for inclusion in our review (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Literature review flowchart.43

Study designs, participants, and settings

Our results included six retrospective cohort studies, one prospective cohort, and one QI study (Table 3). Most (7) included specifically patients with HCC or liver cancer.23–29 Two out of eight studies included patients with cirrhosis without malignancy26,29 and one study included critically ill surgical ICU patients with ESLD who were both pre- and post-transplant.30 Three studies designated their study population as patients with liver cancer, but did not specify if this was HCC.23,24,28 In general, we defined hospice and PC interventions as a multidisciplinary, comprehensive assessment, and management of symptoms and goals of care by trained clinical providers. Four studies evaluated hospice23–25,28 and four evaluated PC interventions26,27,29,30 in various settings (inpatient, outpatient, and home). Two studies evaluated inpatient and home hospice settings, but the authors noted that home hospice was not as well established in Taiwan, so the majority of hospice services were provided in the inpatient setting.24,28 One study evaluated an outpatient PC consultation as part of the liver transplantation evaluation.29 Another study developed and evaluated an inpatient PC program, where transplant surgeons were trained in PC and delivered this with a multidisciplinary team.30

Table 3.

Overview of Included Studies

| Study (author, year of publication) | Study design | Disease process | Intervention or exposure | Setting (inpatient, outpatient, home, both, unknown) | No. of patients (control, experimental) | Outcome measured (HRU, EOLC, PRO, Survival) | Impact on outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies with low risk of bias | Liver cancer | Hospice | Inpatient | 729 | 729 | HRU | Hospice care group had decreased total cost, number of procedures, ICU admissions. | |

| (Hwang et al., 2013)23 | Retrospective cohort | EOLC | Hospice care group had less CPR, defibrillation/cardioversion, and epinephrine injection. | |||||

| (Sanoff et al., 2017)25 | Retrospective cohort | HCC | Hospice | Unknown | 5056 | 2936 | HRU | Less likely to be hospitalized, have an ICU stay. |

| EOLC | Less likely to die in the hospital. | |||||||

| Studies with mod. risk of bias | Quality improvement | DC and HCC | Palliative care consultation | Outpatient | 30 | 30 | PRO | Improvement of symptom burden and depressive symptoms. |

| (Baumann et al., 2015)29 | ||||||||

| Studies with high risk of bias | Liver cancer | Hospice | Both | 644 | 206 | HRU | Hospice was associated with lower costs in the last month of life. | |

| (Chiang and Kao, 2015)28 | Retrospective cohort | Survival | No difference in survival between getting hospice and usual care. | |||||

| (Kao and Chiang 2015)24 | Retrospective cohort | Liver cancer | Hospice | Both | 462 | 2630 | EOLC | Hospice group with less CPR in the last month of life. |

| No difference in receiving chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life. | ||||||||

| Hospice group with fewer ICU admissions. | ||||||||

| HRU | Short-hospice group (<1 month) had more ER visits and hospital admissions. | |||||||

| (Lamba et al., 2012)30 | Prospective cohort, pre/post study | Pre and post-transplant liver disease in surgical ICU | Palliative care program | Inpatient | 79 | 104 | EOLC | Intervention showed an increase in goals of care conversations on physician rounds, increased DNR status, and increase in withdrawal of life support before death. |

| HRU | No difference in ICU or hospital LOS. | |||||||

| (Patel et al., 2017)26 | Retrospective cohort | DC and HCC | Palliative care encounter | Inpatient | 17,358 | 42,328 | HRU | Lower overall costs with palliative care. |

| (Riolfi et al. 2013)27 | Retrospective cohort | HCC | Palliative care service | Home | 11 | 15 | HRU | No difference in mean days in the hospital in last 2 months of life, mean number of hospitalizations in last 2 months of life. |

| EOLC | Patients who received palliative care at home, tended to die more at home. | |||||||

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; DC, decompensated cirrhosis; liver cancer, did not designate specifically HCC; LOS, lengths of stay; ICU, intensive care unit, HRU, healthcare resource utilization; EOLC, end-of-life care; PRO, patient-reported outcomes; CPR, cardiopulmonary resusciation; ER, emergency room; DNR, do-not-resuscitate.

Outcomes

HRU outcomes

Seven out of eight studies examined HRU outcomes.23–28,30 Of these, five studies were found to have high risk of bias. Four studies demonstrated a decrease in utilization with hospice and/or PC.23,25,26,28 Of these, one study examined patients with HCC in National Cancer Institute's SEER—Medicare linkage database from 2004 to 2011 found that the relative risk (RR) of hospitalization for patients who received hospice compared with patients who did not receive hospice was 0.16 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.14–0.19). In addition, the RR of ICU stays for patients on hospice was also lower than patients who did not receive hospice (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.09–0.14).25 Another study examined patients with DC during their terminal hospitalization through the national inpatient sample and found that patients who had PC consultation had lower overall costs of hospitalization when adjusting for all other covariates, with a mean average cost reduction of $9733.26

One study evaluated the effect of hospice in advanced stage liver cancer patients in Taiwan through a national health insurance database from 2000 to 2011. They divided patients into subgroups of patients on hospice for <1 month (short-hospice group) or >1 month (long-hospice group). They show that the short-hospice group had more HRU (ED visits, hospital admissions) compared with the group not on hospice.24 The same authors published another study separately evaluating cost and found that the odds of receiving high-cost care, defined as >$5422 USD in the last month of life, was three times greater (odds ratio [OR] 3.06, 95% CI 2.09–4.60) for patients who did not receive hospice than patients who were on hospice.28

One study evaluated the impact of hospice on geriatric patients with HCC in the national health insurance database in Taiwan from 2001 to 2004. They found that patients on hospice had significantly fewer procedures, including urinary catheterizations, nasogastric tube placement, central venous catheter insertion, endotracheal intubation, abdominal drainage, hemodialysis, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and drainage, chest drainage, esophageal balloon insertion, and total parenteral nutrition (p < 0.001 for all). Patients on hospice also had fewer ICU admissions (0.1% vs. 21.8%, p < 0.001) and shorter LOS for hospitalizations (8 ± 7.7 days vs. 14.1 ± 14.3 days, p < 0.001) compared to those not on hospice.23 Two studies found that PC did not have a statistically significant impact on HRU (mean number of hospitalizations, ICU, and hospital LOS).27,30

End-of-life care

Five of eight studies examined EOLC outcomes and found that PC or hospice have a statistically significant impact.23–25,27,30 Of these, three studies were found to have a high risk of bias. Two studies evaluated location of death and found that the RR of dying in the hospital was lower for patients who received hospice (RR 0.06, 95% CI 0.05–0.07)25 and that patients who received home-based PC more frequently died at home (41.75% vs. 0%, p = 0.007).27 Three studies evaluated resuscitation at the end of life. One study found that patients on hospice received less cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) at the end of life (0.1% vs. 16.6%, p < 0.001),23 and another study found the same effect despite differentiating patients that were on hospice for more than 1 month (OR 0.21) and <1 month (OR 0.09) compared with patients not on hospice (p < 0.001 for both).24 The third study found that their PC program led to an improvement in the number of goals of care conversations held on physician rounds compared to before the intervention (2% vs. 38%, no p-value given). In addition, there was increased documentation of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) status (52%–81%, p = 0.03), withdrawal of life-support measures, including ventilator (11%–43%, p = 0.019), vasopressors (38%–82%, p = 0.008), and artificial nutrition (0%–64%, p = 0.006) after the intervention.30

Patient-reported outcomes

Only one study of eight included evaluated PRO and was found to have moderate risk of bias.29 They found that an outpatient PC consultation as part of standard liver transplant evaluation led to improvement of overall symptoms in 50% of patients with baseline moderate–severe symptoms (p < 0.05) and an improvement of depressive symptoms in 43% of patients (p = 0.003). Overall symptoms were measured by a modified liver-specific Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale and depressive symptoms by Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale. In addition, patients who had more symptoms showed a greater improvement in depressive symptoms (p = 0.001).29

Survival

Only one study evaluated survival and found no difference between the group receiving hospice and the group receiving usual care.24 This study was found to have a high risk of bias.

Discussion

To our knowledge, there have been no other rapid reviews conducted investigating the evidence for PC and hospice intervention in DC/HCC. We found a limited number of studies reporting relevant outcomes for PC and hospice interventions especially in patients with cirrhosis. A majority of studies (seven of eight) examined HCC. They had a variety of study designs, and importantly, no randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A majority had moderate to high risk of bias due to not addressing or adjusting for confounding factors. Most reported reduction in HRU, including total cost of hospitalization, decreased number of hospitalizations, ED visits, and ICU admissions. Our review highlights the need for higher quality clinical trials investigating PC and hospice interventions in these populations.

Of the included studies, compared to HRU, fewer studies examined EOLC (5), PRO (1), and survival (1). The studies that reported EOLC characteristics revealed that patients had less resuscitation and more withdrawal of life support at the end of life, had more goals of care discussions, more comfort-focused care at the end of life, and were more likely to die at home.23–25,27,30 The one study that evaluated PRO showed improvement in symptom burden and depressive symptoms.29 Finally, the one study that evaluated survival found no difference in survival between patients on hospice and without hospice.24

When we examined existing literature, one review by Aslakson et al. found that PC interventions decreased hospital and ICU LOS similar to our review. In addition, they found that this either decreased or did not affect mortality.31 Regarding EOLC, similar to our results, a Cochrane review by Gomes et al. found that PC interventions increased the odds of dying at home and also had a small effect on reducing symptom burden.16 While our review only had one study that evaluated PRO, other reviews have also found a similar effect on PRO. One review by Gaertner et al. examined the effect of specialist PC services on QOL in adults with advanced incurable illness and found in a meta-analysis a small positive effect on QOL and the greatest effect on patients with cancer who received the intervention early.18 A Cochrane review by Haun et al. on early PC interventions in advanced cancer found that they improve QOL and symptom intensity.17 Finally, a review by Kavalieratos et al. found that after adjusting for low risk of bias, there was no significant association between PC intervention and survival, a result similar to our review.15

Our review differs from previously published literature in study characteristics and outcomes. We were unable to locate any RCTs in ESLD. Thus, compared to other reviews, we were not able to perform a meta-analysis and with most studies having moderate to high risk of bias, we are not able to draw broad conclusions. With respect to outcomes, most reviews focus on PRO, and we only had one study that examined this in the DC/HCC population. In addition, we did not find any studies that evaluated caregiver outcomes. Only one study in our review examined the duration of hospice and its impact on outcomes, and in contrast, two of the reviews mentioned above evaluated early PC in cancer patients and found improvement in PRO.17,18 This highlights the need for investigation of both the optimal timing and necessary components of palliative interventions for patients with liver disease. While there are similarities, patients with liver disease differ from other types of cancer and heart failure in the unique trajectory, symptom profile from the point of decompensation to the end of life, decision-making surrounding transplantation and other procedures, and comorbidities, including substance abuse and caregiver burden. Thus, a specific intervention for this population's needs is essential.

Limitations and challenges

With a rapid review methodology, there is higher risk of selection bias, publication bias, and language of publication bias compared to systematic reviews. Selection bias is introduced with not having two reviewers for each step with the expedited timeframe. Publication bias and language of publication bias are introduced with searching published studies in English and limited number of databases. To address this, we searched six databases and included gray literature.

The heterogeneity of interventions and study designs as well as the lack of RCTs are limitations of this rapid review. Therefore, we were not able to conduct a meta-analysis and instead descriptively reported findings from the studies with corresponding risk of bias assessment. We hypothesized that there would be a low number of studies to answer our question and thus were inclusive of all study designs. This led to an overall higher risk of bias and results of these studies should be interpreted with caution. While this makes synthesis of the evidence difficult, it also highlights the gaps of high-quality research in DC/HCC.

We also chose to include studies that had a broader population with respect to disease (cancer, chronic illnesses) if they had specific information on patients with DC/HCC. While reviewing the full texts of articles, a number of them did not have subgroup analysis for patients with DC/HCC and the impact of PC/hospice on outcomes for patients. We attempted to contact a few of the authors to get this information, but we were not successful and due to the nature of this being a rapid review, did not pursue additional data for all the studies that did not include a subgroup analysis.31–37 Other studies were excluded on full-text review if the intervention, comparison group, or examined outcomes did not match our criteria (Table 2).32–42 Another challenge was defining the ESLD study population. This is not well defined in the literature and does not easily translate into clinical practice and research with ICD codes and so on. In general, this means DC defined by having complications of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, and HCC. For the purposes of this review, both DC and HCC are encompassed under ESLD, but we do differentiate the two as related but separate processes. Thus, after starting the initial screening process, we decided to include HCC. To be comprehensive, we repeated the search, and thus, we feel that the question regarding the HCC population was adequately addressed. Short of having each abstract and full-text article reviewed for inclusion/exclusion criteria by two independent authors, we followed the usual process applied in systematic reviews, and thus, despite our methodology being more expedited, it was a rigorous and comprehensive approach.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Our review findings suggested that PC and hospice interventions in patients with DC/HCC reduce healthcare utilization, influenced EOLC, and also improved symptoms. With relatively low number of studies included and heterogeneity of interventions and outcomes, a broader conclusion is difficult to derive. This review does highlight the need for future studies to conduct high-quality RCTs investigating tailored PC and hospice interventions in patients with DC and HCC with outcomes related to HRU, characteristics of EOLC, and PRO. In addition, a greater emphasis is needed for patients with DC (vs. HCC) in future studies.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank University of Alabama at Birmingham Lister Hill Library, specifically, Carolyn Holmes and Geeta Malik for assistance in the search process. This work was supported, in part, by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-37011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. S.K.M. is supported by a T32 in Health Services and Outcomes Research (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ] T32HS013852). The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the NIH or AHRQ.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. : The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States: A population-based study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:690–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Deaths: Final Data for 2014. https://cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/liver-disease.htm (last accessed November30, 2017) [PubMed]

- 3.Transplants by Donor Type: U.S. Transplants Performed January 1, 1998–November 30, 2017. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data (Last accessed November30, 2017)

- 4.Kim WR, Stock PG, Smith JM, et al. : OPTN/SRTR 2011 annual data report: Liver. Am J Transplant 2011;13:73–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L: Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: A systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44:217–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stewart KE, Hart RP, Gibson DP, et al. : Illness apprehension, depression, anxiety, and quality of life in liver transplant candidates: Implications for psychosocial interventions. Psychosomatics 2014;55:650–658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madan A, Barth KS, Balliet W, et al. : Chronic pain among liver transplant candidates. Prog Transplant 2012;4:379–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen L, Leo MC, Chang M, et al. : Symptom distress in patients with end-stage liver disease toward the end of life. Gastroenterol Nurs 2015;38:201–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poonja Z, Brisebois A, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, et al. : Patients with cirrhosis and denied liver transplants rarely receive adequate palliative care or appropriate management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:692–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nardelli S, Pentassuglio I, Pasquale C, et al. : Depression, anxiety and alexithymia symptoms are major determinants of health related quality of life (HRQoL) in cirrhotic patients. Metab Brain Dis 2013;28:239–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bianchi G, Marchesini G, Nicolino F, et al. : Psychological status and depression in patients with liver cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis 2005;37:593–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SH, Oh EG, Lee WH: Symptom experience, psychological distress, and quality of life in Korean patients with liver cirrhosis: A cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2006;43:1047–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth K, Lynn J, Zhong Z, et al. : Dying with end stage liver disease with cirrhosis: Insights from SUPPORT. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000;48(5 Suppl):S122–S130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strand JJ, Mansel JK, Swetz KM: The growth of palliative care. Minn Med 2014;97:39–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. : Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2104–2114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. : Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:1–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. : Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017:1–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaertner J, Siemens W, Meerpohl JJ, et al. : Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital, hospice, or community settings: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2017;358:j2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tricco AC, Antony J, Zarin W, et al. : A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med 2015;13:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H: Expediting systematic reviews: Methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci 2010;5:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, National Institutes of Health U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington DC, https://nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort (Last accessed January31, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hempel S, Shekelle PG, Liu JL, et al. : Development of the quality improvement minimum quality criteria set (QI-MQCS): A tool for critical appraisal of quality improvement intervention publications. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:796–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang SJ, Chang HT, Hwang IH, et al. : Hospice offers more palliative care but costs less than usual care for terminal geriatric hepatocellular carcinoma patients: A nationwide study. J Palliat Med 2013;16:780–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kao YH, Chiang JK: Effect of hospice care on quality indicators of end-of-life care among patients with liver cancer: A national longitudinal population-based study in Taiwan 2000–2011. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanoff HK, Chang Y, Reimers M, et al. : Hospice utilization and its effect on acute care needs at the end of life in Medicare beneficiaries with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Oncol Pract 2017;13:188–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel AA, Walling AM, May FP, et al. : Palliative care and healthcare utilization for patients with end-stage liver disease at the end of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1612–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riolfi M, Buja A, Zanardo C, et al. : Effectiveness of palliative home-care services in reducing hospital admissions and determinants of hospitalization for terminally ill patients followed up by a palliative home-care team: A retrospective cohort study. Palliat Med 2014;28:403–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiang JK, Kao YH: The impact of hospice care on survival and cost saving among patients with liver cancer: A national longitudinal population-based study in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:1049–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumann AJ, Wheeler DS, James M, et al. : Benefit of early palliative care in end-stage liver disease patients awaiting liver transplantation. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:882–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamba S, Murphy P, McVicker S, et al. : Changing end-of-life care practice for liver transplant service patients: Structured palliative care intervention in the surgical intensive care unit. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;44:508–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aslakson R, Cheng J, Vollenweider D, et al. : Evidence-based palliative care in the intensive care unit: A systematic review of interventions. J Palliat Med 2014;17:219–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Podymow T, Turnbull J, Coyle D: Shelter-based palliative care for the homeless terminally ill. Palliat Med 2006;20:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sano M, Fushimi K: Association of palliative care consultation with reducing inpatient chemotherapy use in elderly patients with cancer in Japan: Analysis using a nationwide administrative database. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2017;34:685–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kao CY, Wang HM, Tang SC, et al. : Predictive factors do-not-resuscitate designation among terminally ill cancer patients receiving care from a palliative care consultation service. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:271–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loke SS, Rau KM: Differences between inpatient hospice care and in-hospital nonhospice care for cancer patients. Cancer Nurs 2011;34:E21–E26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hung YS, Chen CH, Yeh KY, et al. : Potential benefits of palliative care for polysymptomatic patients with late-stage nonmalignant disease in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2013;112:406–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chou WC, Hung YS, Kao CY, et al. : Impact of palliative care consultative service on disease awareness for patients with terminal cancer. Suppor Care Cancer 2013;21:1973–1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walling AM, Schreibeis-Baum H, Pimstone N, et al. : Proactive case finding to improve concurrently curative and palliative care in patients with end-stage liver disease. J Palliat Med 2015;18:378–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelly SG, Campbell TC, Hillman L, Said A, et al. : The utilization of palliative care services in patients with cirrhosis who have been denied liver transplantation: A single center retrospective review. Ann Hepatol 2017;16:395–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mor V, Joyce NR, Coté DL, et al. : The rise of concurrent care for veterans with advanced cancer at the end of life. Cancer 2016;122:782–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng SY, Dy S, Fang PH, et al. : Evaluation of inpatient multidisciplinary palliative care unit on terminally ill cancer patients from providers' perspectives: A propensity score analysis. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2013;43:161–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perri GA, Bunn S, Oh YJ, et al. : Attributes and outcomes of end stage liver disease as compared with other noncancer patients admitted to a geriatric palliative care unit. Ann Palliat Med 2016,5:76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]