Dear Editor:

Often, healthcare decisions, particularly those at the end of life, are made by surrogate decision-makers.1 In the United States, statutes pertaining to decision making are state-specific, and a recent study found significant variability in both statutory ordering of surrogates and procedures to establish decision-makers.2 In theory, tools such as advance directive (AD) forms help guide patients, families, and healthcare providers through the process of decision making. However, the ability of providers to use such tools may be complicated by differences in terminology used, accessibility of forms, and concerns about forms' validity. Consequently, we sought to examine current state-level variability in terminology and accessibility of AD forms.

AD forms for all states (including the District of Columbia) were obtained from the American Association of Retired Persons (www.aarp.org). From them, we abstracted key information, including the following: (1) terms used for the designated decision-maker (DDM; person chosen by the patient to make healthcare decisions), (2) terms used for the statutory default substitute (SDS; person to whom the decision defaults in the absence of a DDM), (3) existence of a filing location, and (4) the length of time that the form is valid. We quantified the percentage of states using particular terms for the DDM/SDS. To quantify the potential impact of existing variability on providers and patients, we calculated the percentage of physicians practicing outside of the state, in which they were trained using data from the 2015 Medicare Physician Compare dataset (https://data.medicare.gov) and the 2016 American Association of Medical Colleges Physician Specialty Data Report (www.aamc.org), as well as the percentage of people dying outside of their state of residence using death certificate data for 2015 (Multiple Cause-of-Death Mortality Data, National Center for Health Statistics). This study was declared exempt by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

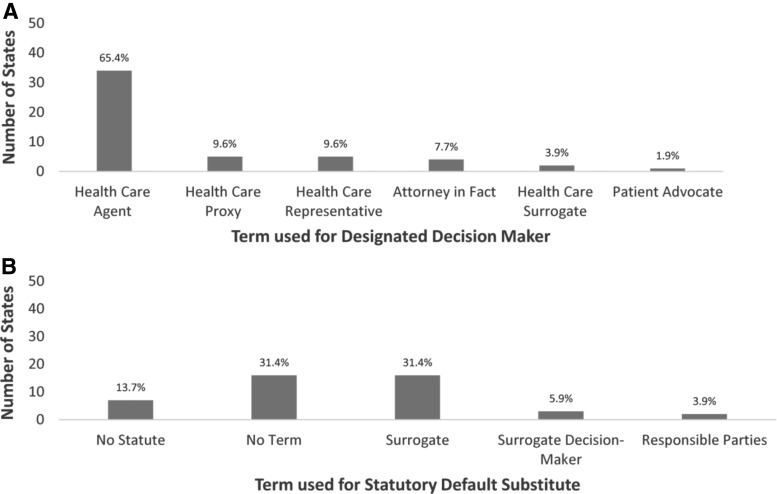

The most common term for the DDM used in AD forms was “healthcare agent” (n = 34), with “healthcare proxy” (n = 5), “healthcare representative” (n = 5), “attorney-in-fact” (n = 4), “healthcare surrogate” (n = 2), and “patient advocate” (n = 1) comprising the rest (Fig. 1). Substantial variability also existed in terms for the SDS, with many states not specifying a term (n = 16), and “surrogate” or “surrogate decision-maker” being the most common term used (n = 18) (Fig. 1). The majority of states did not have a place to file AD forms with only 11 states specifying a location (AD registry available, n = 9; state government office, n = 2). There was no variability in length of time that the AD form is valid (until revoked). The majority of physicians do not practice in the same state where they completed medical school (61.5%, n = 575,064) or postgraduate training (52.7%, n = 813,711). In 2015, 3.1% of people died outside their state of primary residence (n = 83,973).

FIG. 1.

Variability of terminology used in surrogate decision making in the United States. Panel (A) lists terms used for the designated decision-maker in an advance directives form throughout the United States, including the District of Columbia. Panel (B) lists terms used for the statutory default substitute. For panel (B), additional terms used include “proxy,” “proxy decision-maker,” “next of kin,” “family members,” “healthcare representative,” “appropriate individual” and “substituted consent” (n = 1 for all).

At the national level, inconsistent terminology for DDMs and SDSs and the lack of filing locations for AD forms may create unnecessary stress and confusion for providers as they navigate an already fraught process.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hua is supported by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award K08AG051184 from the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research.

References

- 1.Torke AM, Sachs GA, Helft PR, et al. : Scope and outcomes of surrogate decision making among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:370–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeMartino ES, Dudzinski DM, Doyle CK, et al. : Who decides when a patient can't? Statutes on alternate decision makers. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1478–1482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]