Abstract

Objectives

Children’s exposure to racism via caregiver experience (vicarious racism) is associated with poorer health and development. However, the relationship with child healthcare utilisation is unknown. We aimed to investigate (1) the prevalence of vicarious racism by child ethnicity; (2) the association between caregiver experiences of racism and child healthcare utilisation; and (3) the contribution of caregiver socioeconomic position and psychological distress to this association.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of two instances of the New Zealand Health Survey (2006/2007: n=4535 child–primary caregiver dyads; 2011/2012: n=4420 dyads).

Main outcome measures

Children’s unmet need for healthcare, reporting no usual medical centre and caregiver-reported dissatisfaction with their child’s medical centre.

Results

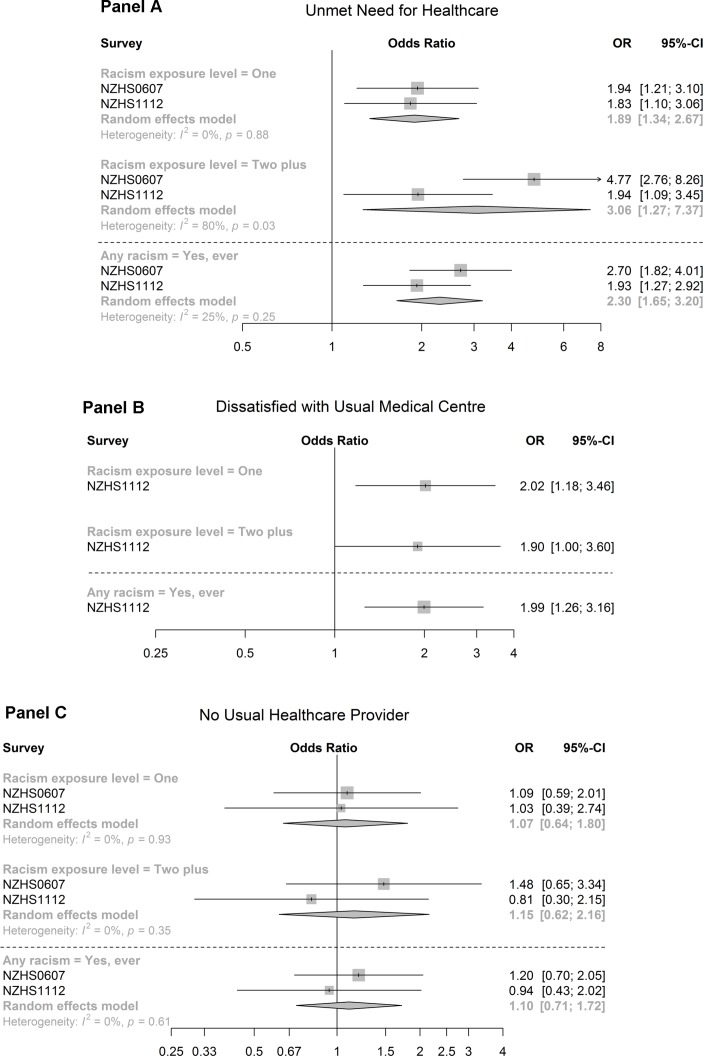

The prevalence of reporting ‘any’ experience of racism was higher among caregivers of indigenous Māori and Asian children (30.0% for both groups in 2006/2007) compared with European/Other children (14.4% in 2006/2007). Vicarious racism was independently associated with unmet need for child’s healthcare (OR=2.30, 95% CI 1.65 to 3.20) and dissatisfaction with their child’s medical centre (OR=2.00, 95% CI 1.26 to 3.16). Importantly, there was a dose–response relationship between the number of reported experiences of racism and child healthcare utilisation (eg, unmet need: 1 report of racism, OR=1.89, 95% CI 1.34 to 2.67; 2+ reports of racism, OR=3.06, 95% CI 1.27 to 7.37). Adjustment for caregiver psychological distress attenuated the association between caregiver experiences of racism and child healthcare utilisation.

Conclusions

Vicarious racism is a serious health problem in New Zealand disproportionately affecting Māori and Asian children and significantly impacting children’s healthcare utilisation. Tackling racism may be an important means of improving inequities in child healthcare utilisation.

Keywords: racism, health care utilisation, child, indigenous, inequities

What is already known on this topic?

Inequities in healthcare utilisation between children of different racial/ethnic groups have been widely documented.

Perceived experience of racism is associated with lower healthcare utilisation in adults.

The impact of caregiver experiences of racism on child healthcare utilisation is currently unknown.

What this study adds?

Caregiver experiences of racism are independently associated with measures of poorer child healthcare utilisation.

Psychological distress in caregivers may partially mediate this association.

Tackling racism may be an important means of improving healthcare utilisation for children from minoritised ethnic groups, including indigenous and migrant children.

Introduction

Access to high-quality healthcare is enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child1 and is associated with better health outcomes for children. However, racial/ethnic and socioeconomic inequities in healthcare utilisation (‘HCU’) exist,2 even in settings of universal healthcare such as Australia3 and Canada.4 New Zealand (total population: ~4.8 million) currently offers publicly funded, free or low-cost primary care services for children under 13 years and delivery of some services by indigenous Māori and Pacific healthcare organisations.5 Despite this, Māori and Pacific children have higher unmet need for primary healthcare and are more likely to have unfilled prescriptions than children from Asian or European ethnic groups,6–8 suggesting factors other than cost and service delivery/location are involved.

Racism is internationally recognised as a pervasive social determinant of child health.9 10 Although direct forms of racism incur significant health risks for children, emergent evidence suggests that exposure to ‘vicarious’ racism, via parent/caregiver experience, can have detrimental consequences on child health. For example, in the UK Millennium Cohort Study, maternal experiences of racism were associated with greater socioemotional difficulties and poorer spatial ability among their children.11 12 Similarly, in a survey of Australian indigenous communities, caregiver experiences of racism increased the odds of children having at least two recent illnesses in the previous fortnight.13 In New Zealand, maternal experiences of racism in healthcare were associated with subsequent increased risk of infant hospitalisation for infectious diseases.14 Vicarious racism has been defined as ‘…hearing about or seeing another person’s experience of racism15 16 as well as carers or close family members experiencing discrimination that may or may not be witnessed by children and adolescents’ (p1672).17 Although the exact pathways through which vicarious racism influences child health are not fully understood, a recent systematic review suggested that racism degrades family relationships and increases parenting stress, which in turn might influence parental practices and coping strategies.10 Vicarious racism could also influence child HCU given that parents/caregivers make the majority of healthcare decisions for their children.10 18 However, research on this relationship is scant, with none on indigenous children.9 10

This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of vicarious racism for children (0–14 years), and to investigate the association between vicarious racism and measures of low child HCU. We also explored the contribution of two potential pathway variables in the relationship: socioeconomic position (SEP), given associations with racism19 and low HCU,7 20 and caregiver psychological distress, given associations between racism and poor mental health in adults9 21 and associations between caregiver mental health (eg, depression, parenting stress, anxiety) and low HCU in their children.22–24

Methods

We analysed cross-sectional data from the New Zealand Health Survey (NZHS), which used multistage, stratified, probability-proportional-to-size sampling design, with three steps used to achieve the area-based sample. Increased sampling of Māori, Pacific and Asian ethnic groups was undertaken to improve statistical precision of estimates for these groups.25 One adult (≥15 years, usually resident at that dwelling) and up to one child (0–14 years, usually resident at that dwelling at least 50% of the time) were selected from each household (full methodology reported elsewhere25 26). We used data from the two most recent instances of the NZHS to include a racism module in the adult questionnaire (2006/2007 and 2011/2012).

Analytical sample restriction

Child questionnaires were completed by their primary caregiver; however, the adult respondent sampled from the house was not always the primary caregiver. For example, in 2006/2007, 35.2% of children did not have their primary caregiver included in the adult sample, which means there were no racism data for their caregiver, since proxy respondents did not complete the racism module. Consequently, this analysis was restricted to those children whose primary caregiver was also in the adult survey. As adult respondents were randomly selected within a household, those caregivers completing the adult survey should not systematically differ from those caregivers who did not complete the adult survey, which should prevent selection bias in the paired sample. The analysis included 4535 child–primary caregiver dyads in the 2006/2007 NZHS (92.2% of children matched to caregiver) and 4420 dyads in the 2011/2012 NZHS (97.0% of children matched).

Outcome variables

Three outcome measures were investigated. Having access to a usual healthcare provider was determined by asking if the child had a general practitioner (‘GP’) or medical centre they would usually go to if unwell (modelled outcome was ‘no’). Unmet need was measured by asking if there had been any time in the last 12 months when their child needed to see a GP but could not see one at all (modelled outcome was ‘yes’). Caregiver satisfaction with child’s usual medical centre was determined for those children who had visited their usual healthcare provider in the previous 12 months (n=3049 child–primary caregiver dyads, 2011/2012 NZHS only), with responses dichotomised as ‘very dissatisfied/dissatisfied/neither satisfied or dissatisfied’ (the modelled outcome) versus ‘satisfied/very satisfied’.

Exposure variables

Two measures of vicarious racism based on the caregiver’s experience were used (further detail on racism measures and coding can be found in online supplementary appendix A): any racial discrimination ever in a person’s lifetime (exposure defined as answering yes to any of the five questions in the racism module, regardless of time frame); and level of racial discrimination (count of yes responses across the racism module, regardless of time frame: no reports, 1 report or 2+ reports).27

archdischild-2017-313866supp001.docx (18.3KB, docx)

Covariates

Ethnicity was measured using the 2001 NZ Census ethnicity question, which allows respondents to self-identify with one or more ethnic groups.28 The question provides several ethnic group response options, an ‘Other’ category and a free-text field. The 2011/2012 NZHS data set provided ethnicity categories aggregated as Māori, Pacific, Asian and a European/Other grouping, which could not be disaggregated; therefore, we used the combined European/Other as a comparator group for both NZHS data sets for consistency. In the 2006/2007 NZHS data, the European/Other group was predominantly European (99%), with approximately 1% in the ‘Other’ category.

Caregiver gender (male vs female) and age group (25–44, 45–64, 65–74, ≥75 years vs 15–24 years) were included in all models. When the outcome of interest was ‘caregiver satisfaction with their child’s medical centre’, we also controlled for caregiver satisfaction with their own medical centre (very dissatisfied/dissatisfied/neither satisfied or dissatisfied vs satisfied/very satisfied).

Potential pathway variables

Caregiver SEP was measured using their highest educational qualifications (no qualifications vs at least secondary school qualifications) and neighbourhood deprivation (New Zealand Deprivation Index 2006 (NZDep06) quintiles: 1=least deprived and 5=most deprived29). Caregiver mental health was measured using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale,30 a 10-item scale that provides a global measure of psychological distress in the previous 4 weeks (K10, treated as a continuous variable).

Data analysis

Unadjusted prevalence estimates were calculated for outcomes and exposures, for the total Māori, Pacific and Asian groupings and the mutually exclusive European/Other grouping. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to investigate the independent association between caregiver experiences of racism and each child HCU measure, adjusted for caregiver ethnicity, gender, age group, SEP and satisfaction with usual medical centre (for models investigating child dissatisfaction with care). In multiple regression analyses, ethnicity was prioritised as Māori, Pacific, Asian and European/Other.28

To investigate how caregiver SEP and psychological distress influenced the association between vicarious racism and child HCU, we built several models adding covariates sequentially as follows: caregiver racism measures (baseline model, M0); caregiver ethnicity, gender, age group (M1); caregiver dissatisfaction with care (M2a, where the outcome was satisfaction with child’s usual healthcare provider); caregiver SEP (M2b); and psychological distress (M3). The complex sample structure of the NZHS was handled in analysis by accounting for stratification, clusters and inverse sampling weights (using the child’s sampling weight in the NZHS data set).

Results from the two surveys were combined using random-effects meta-analysis. This calculated a pooled estimate for each parameter (ie, each log OR and associated SE), with random-effects weightings based on the inverse variance of the parameter estimates from each survey instance. The survey data sets were analysed using SAS V.9.4; meta-analysis was conducted in R V.3.2 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) using the ‘meta’ package. OR and 95% CI for the racism variables and each covariate included in the full models can be found in online supplementary tables.

archdischild-2017-313866supp002.docx (38.8KB, docx)

Results

Caregivers of Māori and Pacific children were younger, over-represented in the most deprived neighbourhoods (NZDep06 quintile 5) and more likely to report no secondary school qualifications compared with caregivers of European/Other children. Most primary caregivers were female (table 1). The prevalence of ‘any’ experience of racism was higher among caregivers of Māori (30.0% in 2006/2007; 26.7% in 2011/2012; table 2) and Asian children (30.0% in 2006/2007; 30.1% in 2011/2012) compared with those of European/Other children (14.4% in 2006/2007; 9.0% in 2011/2012). Caregivers of Māori and Asian children were also more likely to report two or more experiences of racism than caregivers of European/Other children (table 2).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile of children with matched caregiver data in the 2006/2007 NZHS (n=4535) and 2011/2012 NZHS (n=4420), by child ethnicity*

| Sociodemographic variables | Māori children | Pacific children | Asian children | European/Other children | ||||

| 2006/2007 n=1769 |

2011/2012 n=1558 |

2006/2007 n=732 |

2011/2012 n=715 |

2006/2007 n=703 |

2011/2012 n-427 |

2006/2007 n=1619 |

2011/2012 n=1986 |

|

| Unweighted % (95% CI) | Unweighted % (95% CI) | Unweighted % (95% CI) | Unweighted % (95% CI) | Unweighted % (95% CI) | Unweighted % (95% CI) | Unweighted % (95% CI) | Unweighted % (95% CI) | |

| Total | 39.0 (37.6 to 40.4) |

35.3 (33.8 to 36.7) |

16.1 (15.1 to 17.2) |

16.2 (15.1 to 17.3) |

15.5 (14.5 to 16.6) |

9.7 (8.8 to 10.5) |

35.7 (34.3 to 37.1) |

44.9 (43.5 to 46.4) |

| Child gender | ||||||||

| Female | 47.4 (45.0 to 49.7) |

49.0 (46.5 to 51.5) |

45.4 (41.8 to 49.0) |

48.4 (44.7 to 52.1) |

48.4 (44.7 to 52.1) |

46.1 (41.4 to 50.9) |

47.3 (44.9 to 49.8) |

47.7 (45.5 to 49.9) |

| Male | 52.6 (50.3 to 55.0) |

51.0 (48.5 to 53.5) |

54.7 (51.1 to 58.3) |

51.6 (47.9 to 55.3) |

51.6 (47.9 to 55.3) |

53.9 (49.1 to 58.6) |

52.7 (50.3 to 55.1) |

52.3 (50.1 to 54.5) |

| Child age group (years) | ||||||||

| 0–4 | 37.5 (35.3 to 39.8) |

42.1 (39.7 to 44.6) |

35.4 (31.9 to 38.9) |

42.2 (38.6 to 45.9) |

37.7 (34.1 to 41.3) |

45.7 (40.9 to 50.4) |

31.0 (28.7 to 33.2) |

38.6 (36.5 to 40.8) |

| 5–9 | 31.2 (29.1 to 33.4) |

26.6 (24.4 to 28.8) |

31.7 (28.3 to 35.1) |

28.4 (25.1 to 31.7) |

28.6 (25.3 to 31.9) |

27.2 (22.9 to 31.4) |

28.9 (26.7 to 31.1) |

29.2 (27.2 to 31.2) |

| 10–14 | 31.3 (29.0 to 33. 4) |

31.3 (29.0 to 33.6) |

32.9 (29.5 to 36.3) |

29.4 (26.0 to 32.7) |

33.7 (30.2 to 37.2) |

27.2 (22.9 to 31.4) |

40.2 (37.8 to 42.5) |

32.2 (30.2 to 34.2) |

| Caregiver ethnicity* | ||||||||

| Māori | 85.0 (83.3 to 86.6) |

76.5 (74.4 to 78.6) |

22. 7 (19.6 to 25.7) |

23.1 (20.0 to 26.2) |

5.3 (3.6 to 6.9) |

4.7 (2.7 to 6.7) |

2.1 (1.4 to 2.8) |

2.8 (2.1 to 3.6) |

| Pacific | 7.9 (6.7 to 9.2) |

7.8 (6.4 to 9.1) |

77.9 (74.9 to 80.9) |

76.4 (73.2 to 79.5) |

2.4 (1.3 to 3.6) |

6.6 (4.2 to 8.9) |

0.4 (0.1 to 0.7) |

0.4 (0.1 to 0.7) |

| Asian | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.4) |

1.5 (0.9 to 2.1) |

3.1 (1.9 to 4.4) |

3.1 (1.8 to 4.3) |

91.51 (89.4 to 93.5) |

84.1 (80.6 to 87.6) |

0.5 (0.2 to 0.8) |

0.6 (0.3 to 0.9) |

| European/Other | 10.3 (8.9 to 11.8) |

19.0 (17.1 to 21.0) |

5.6 (3.9 to 7.3) |

7.7 (5.7 to 9.6) |

3.7 (2.3 to 5.1) |

9.6 (6.8 to 12. 4) |

97.2 (96.4 to 98.0) |

96.2 (95.4 to 97.1) |

| Caregiver gender | ||||||||

| Female | 67.8 (65.7 to 70.0) |

71.3 (69.1 to 73.6) |

64.2 (60.7 to 67.7) |

72.2 (68.9 to 75.5) |

60.2 (56.6 to 63.8) |

57.4 (52.7 to 62.1) |

59.9 (57.5 to 62.2) |

62.6 (60.4 to 64.7) |

| Male | 32.2 (30.0 to 34.3) |

28.7 (26.4 to 30.9) |

35.8 (32.3 to 39.3) |

27.9 (24.6 to 31.1) |

39.9 (36.2 to 43.5) |

42.6 (37.9 to 47.3) |

40.2 (37.8 to 42.5) |

37.5 (35.3 to 39.6) |

| Caregiver age group (years) | ||||||||

| 15–24 | 20.2 (18.4 to 22.1) |

19.1 (17.1 to 21.0) |

20.1 (17.2 to 23.0) |

21.7 (18.7 to 24.7) |

10.4 (8.1 to 12.6) |

8.9 (6.2 to 11.6) |

9.8 (8.4 to 11.3) |

11.3 (9.8 to 12.6) |

| 25–34 | 34.3 (32.1 to 36.5) |

29.9 (27.6 to 32.2) |

31.4 (28.1 to 34.8) |

30.5 (27.1 to 33.9) |

22.5 (19.4 to 25.6) |

26.9 (22.7 to 31.1) |

21.7 (19.7 to 23.8) |

22.8 (21.0 to 24.7) |

| 35–44 | 28.5 (26.4 to 30.6) |

31.6 (29.3 to 33.9) |

30.1 (26.7 to 33.4) |

26.2 (22.9 to 29.4) |

45.2 (41.6 to 48.9) |

41.0 (36.3 to 45.7) |

46.0 (43.5 to 48.4) |

43.8 (41.6 to 45.9) |

| 45–54 | 12.4 (10.8 to 13.9) |

13.2 (11.5 to 14.9) |

13.4 (10.9 to 15.9) |

14.6 (12.0 to 17.1) |

15.7 (13.0 to 18.3) |

15.2 (11.8 to 18.6) |

19.6 (17.7 to 21.5) |

18.4 (16.7 to 20.1) |

| 55–64 | 3.3 (2.5 to 4.1) |

4.8 (3.7 to 5.8) |

3.6 (2.2 to 4.9) |

5.7 (4.0 to 7.4) |

3.6 (2.2 to 4.9) |

4.7 (2.7 to 6.7) |

1.9 (1.2 to 2.5) |

2.6 (1.9 to 3.3) |

| 65–74 | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.1) |

1.0 (0.5 to 1.5) |

0.8 (0.2 to 1.5) |

1.3 (0.4 to 2.1) |

2.4 (1.3 to 3.6) |

2.1 (0.8 to 3.5) |

0.8 (0.4 to 1.2) |

0.9 (0.5 to 1.3) |

| ≥75 | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.0) |

0.5 (0.1 to 0.8) |

0.7 (0.1 to 1.3) |

0.1 (0.0 to 0.4) |

0.3 (0.0 to 0.7) |

1.2 (0.2 to 2.2) |

0.3 (0.0 to 0.5) |

0.4 (0.1 to 0.6) |

| Caregiver neighbourhood socioeconomic deprivation (NZDep06 index) | ||||||||

| Quintile 1 | 8.3 (7.0 to 9.5) |

6.3 (5.0 to 7.4) |

5.9 (4.2 to 7.6) |

4.3 (2.8 to 5.8) |

14.4 (11.8 to 17.0) |

13.6 (10.3 to 16.8) |

26.3 (24.1 to 28.4) |

23.3 (21.5 to 25.2) |

| Quintile 2 | 11.1 (9. 7 to 12.6) |

7.9 (6.6 to 9.2) |

7.8 (5.9 to 9.7) |

6.3 (4.5 to 8.1) |

16.1 (13.4 to 18.8) |

20.4 (16.6 to 24.2) |

22.2 (20.2 to 24.3) |

21.1 (19.3 to 22.8) |

| Quintile 3 | 16.0 (14.3 to 17.7) |

14.8 (13.1 to 16.6) |

14.1 (11.6 to 16.6) |

10.1 (7.9 to 12.3) |

20.5 (17.5 to 23.5) |

16.9 (13.3 to 20.4) |

21.9 (19.9 to 23.9) |

24.1 (22.2 to 26.0) |

| Quintile 4 | 21.7 (19.7 to 23.6) |

22.5 (20.5 to 24.6) |

18.4 (15.6 to 21.3) |

21.4 (18.4 to 24.4) |

30.4 (27.0 to 33.8) |

23.2 (19.2 to 27.2) |

18.6 (16.7 to 20.5) |

18.2 (16.5 to 19.9) |

| Quintile 5 | 43.0 (40.7 to 45.3) |

48.5 (46.0 to 51.0) |

53.8 (50.2 to 57.4) |

57.9 (54.3 to 61.5) |

18.6 (15.8 to 21.5) |

26.0 (21.8 to 30.2) |

11.0 (9.5 to 12.5) |

13.4 (11.9 to 14.9) |

| Caregiver highest educational qualification | ||||||||

| No secondary school | 42.3 (40.0 to 44.6) |

40.3 (37.9 to 42.8) |

34.4 (30.9 to 37.8) |

29.1 (25.7 to 32.4) |

9.7 (7.5 to 11.9) |

12.5 (9.4 to 15.7) |

17. 8 (15.9 to 19.7) |

18.0 (16.4 to 19.6) |

| Secondary school or higher | 57.7 (55.4 to 60.0) |

59.7 (57.3 to 62.1) |

65.6 (62.2 to 69.1) |

71.0 (67.6 to 74.3) |

90.3 (88.1 to 92.5) |

87.5 (84.4 to 90.7) |

82.2 (80.3 to 84.1) |

82.0 (80.4 to 83.6) |

*Self-identified ethnicity data were classified as total Māori, total Pacific, total Asian and prioritised European/Other. The ‘total’ ethnic categories allow for individuals to be counted once in each ethnic grouping they identify with. These categories, therefore, may overlap.

NZDep06, New Zealand Deprivation Index 2006; NZHS, New Zealand Health Survey.

Table 2.

Weighted prevalence of key exposure and outcome variables in the 2006/2007 and 2011/2012 New Zealand Health Survey, by child ethnicity*

| Māori children | Pacific children | Asian children | European/Other children | |||||

| 2006/2007 | 2011/2012 | 2006/2007 | 2011/2012 | 2006/2007 | 2011/2012 | 2006/2007 | 2011/2012 | |

| Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | Weighted % (95% CI) | |

| Key outcome variables | ||||||||

| Child health service utilisation | ||||||||

| No usual healthcare provider | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.1) |

2.9 (1.7 to 4.2) |

1.6 (0.4 to 2.8) |

2.4 (1.1 to 3.8) |

8.0 (5.6 to 10.4) |

4.7 (2.4 to 6.9) |

1.8 (1.0 to 2.6) |

2.6 (1.7 to 3.4) |

| Unmet need for healthcare | 6.6 (5.0 to 8.2) |

6.9 (5.2 to 8.5) |

4.1 (2.6 to 5.6) |

7.1 (4.9 to 9.4) |

4.0 (2.0 to 6.0) |

4.6 (2.3 to 6.8) |

3.1 (2.2 to 4.1) |

4.1 (2.9 to 5.3) |

| Dissatisfied with child’s medical centre† | NA | 10.5 (8.3 to 12.7) |

NA | 8.0 (5.4 to 10.6) |

NA | 9.2 (3.9 to 14.5) |

NA | 6.7 (5.1 to 8.4) |

| Key exposure variables | ||||||||

| Caregiver perceived racism (‘ever’) | ||||||||

| Any racial discrimination | 30.0 (27.2 to 33.0) |

26.7 (23.6 to 29.8) |

21.1 (17.5 to 24.7) |

22.0 (17.7 to 26.3) |

30.0 (26.0 to 34.0) |

30.1 (24.8 to 35.3) |

14.4 (12.5 to 16.3) |

9.0 (7.5 to 10.5) |

| Level of racial discrimination (‘ever’) | ||||||||

| 1 report | 18.8 (16.3 to 21.3) |

16.4 (13.6 to 19.3) |

14.7 (11.3 to 18.0) |

13.1 (9.9 to 16.3) |

19.3 (16.1 to 22.6) |

16.8 (13.2 to 20.5) |

11.4 (9.6 to 13.1) |

6.4 (5.2 to 7.7) |

| 2 or more reports | 11.2 (9.3 to 13.2) |

10.0 (8.0 to 11.9) |

6.4 (4.5 to 8.3) |

8.4 (5.7 to 11.0) |

10.6 (8.1 to 13.1) |

12.4 (7.8 to 17.1) |

3.1 (2.2 to 4.0) |

2.5 (1.6 to 3.3) |

*Self-identified ethnicity data were classified as total Māori, total Pacific, total Asian and prioritised European/Other. The ‘total’ ethnic categories allow for individuals to be counted once in each ethnic grouping they identify with. These categories, therefore, may overlap.

†This variable was only available for those children who had visited their usual medical centre in the previous 12 months, 2011/2012 NZHS. Response options were categorised as ‘very dissatisfied/dissatisfied/neither satisfied or dissatisfied’ versus ‘very satisfied/satisfied’.

NA, not applicable.

figure 1 presents the findings from the models used to investigate the independent association between vicarious racism and child healthcare utilisation. Children of caregivers who reported ‘any’ racism had higher odds of unmet need for healthcare (pooled OR=2.30, 95% CI 1.65 to 3.2; figure 1, bottom third of panel A) and dissatisfaction with usual medical centre (OR=1.99, 95% CI 1.26 to 3.16; figure 1, bottom third of panel B) in fully adjusted models.

Figure 1.

Forest plots with ORs and 95% CI of the association between caregiver experiences of racism and (panel A) unmet need for healthcare, (panel B) caregiver dissatisfaction with child’s usual medical centre and (panel C) reporting no usual healthcare centre. Models adjusted for caregiver ethnicity, gender, age, socioeconomic position and caregiver dissatisfaction with own care (panel B only). NZHS, New Zealand Health Survey.

Vicarious racism was independently associated with child HCU in models that used the three-level racism variable (figure 1, upper two-thirds of panels A–C). For example, the odds of reporting dissatisfaction with their usual medical centre were OR=2.02 for children whose caregivers reported one racism experience (top third of panel B) and OR=1.90 for those reporting ≥2 experiences in fully adjusted models (middle third of panel B). Meta-analysis revealed a dose–response relationship between the ‘level’ of racism reported and child unmet need for healthcare in the fully adjusted random-effects model (1 report of racism: pooled OR=1.89, 95% CI 1.34 to 2.67; 2+ reports of racism: pooled OR=3.06, 95% CI 1.27 to 7.37; panel A). There was no strong evidence of association between vicarious racism and having a usual healthcare provider.

Table 3 shows the impact of caregiver SEP and psychological distress on the association between vicarious racism and child HCU. Vicarious racism was strongly associated with unmet need for care in unadjusted (M0: OR=2.53, 95% CI 1.68 to 3.80) and ethnicity/gender/age-adjusted models (M1: OR=2.34, 95% CI 1.65 to 3.32). While adjustment for SEP had negligible impact on this relationship (M2b: OR=2.30, 95% CI 1.65 to 3.20), there was a substantial reduction in the association following adjustment for K10 (M3: OR=1.89, 95% CI 1.14 to 3.12). This pattern of greater relative attenuation of the OR after adjustment for K10 than for SEP was apparent for each HCU measure (table 3). Caregiver psychological distress also influenced the dose–response relationship between the ‘level’ of vicarious racism and child HCU (lower half of table 3).

Table 3.

Association between caregiver experiences of racism and child health service utilisation, with findings presented for unadjusted models (M0) to models that are adjusted for potential confounders and pathway variables

| Dissatisfied with child’s medical centre*† | No usual healthcare provider | Unmet need for healthcare | ||

| OR (95% CI) | Pooled OR (95% CI) | Pooled OR (95% CI) | ||

| Model for any racial discrimination (‘ever’) | ||||

| M0: unadjusted | 2.48 (1.62 to 3.81) | 1.23 (0.81 to 1.90) | 2.53 (1.68 to 3.80) | |

| M1: ethnicity, gender and age | 2.39 (1.56 to 3.65) | 1.10 (0.71 to 1.72) | 2.34 (1.65 to 3.32) | |

| M2a: caregiver satisfaction with own health service | 1.98 (1.25 to 3.14) | NA | NA | |

| M2b: neighbourhood deprivation, highest educational qualification | 2.00 (1.26 to 3.16) | 1.11 (0.71 to 1.72) | 2.30 (1.65 to 3.20) | |

| M3: psychological distress | 1.76 (1.11 to 2.79) | 1.07 (0.67 to 1.71) | 1.89 (1.14 to 3.12) | |

| Model for level of racial discrimination | Level | |||

| M0: unadjusted | 1 report 2+ reports |

2.40 (1.53 to 3.76) 2.60 (1.23 to 5.51) |

1.18 (0.71 to 1.98) 1.28 (0.61 to 2.67) |

2.07 (1.48 to 2.91) 3.38 (1.22 to 9.35) |

| M1: ethnicity, gender and age | 1 report 2+ reports |

2.29 (1.42 to 3.68) 2.55 (1.26 to 5.17) |

1.08 (0.64 to 1.81) 1.15 (0.61 to 2.15) |

1.93 (1.38 to 2.71) 3.09 (1.23 to 7.72) |

| M2a: caregiver satisfaction with own health service | 1 report 2+ reports |

1.94 (1.14 to 3.30) 2.00 (1.03 to 3.88) |

NA NA |

NA NA |

| M2b: neighbourhood deprivation, highest educational qualification | 1 report 2+ reports |

2.02 (1.18 to 3.46) 1.90 (1.00 to 3.60) |

1.07 (0.64 to 1.80) 1.15 (0.62 to 2.16) |

1.89 (1.34 to 2.67) 3.06 (1.27 to 7.37) |

| M3: psychological distress | 1 report 2+ reports |

1.81 (1.08 to 3.04) 1.67 (0.84 to 3.35) |

1.04 (0.61 to 1.78) 1.05 (0.47 to 2.35) |

1.60 (1.12 to 2.29) 2.43 (0.84 to 6.99) |

*This variable was only available for the 2011/2012 New Zealand Health Survey; thus, meta-analytical techniques were note used. These models were additionally adjusted for caregiver satisfaction with own health service (M2a).

†Response options were categorised as ‘very dissatisfied/dissatisfied/neither satisfied or dissatisfied’ versus ‘very satisfied/satisfied’.

NA, not applicable.

Discussion

The present study identified strong associations between caregiver experiences of racism and unmet need and caregiver-reported dissatisfaction with their child’s usual medical centre. These relationships were independent of caregiver ethnicity, age, gender and (in some models) dissatisfaction with their own medical centre. Furthermore, findings suggest that the association between vicarious racism and child HCU may be operating via higher levels of psychological distress among caregivers. This finding is important and aligns with evidence from longitudinal studies showing that caregiver mental health mediates the association between racism and child health outcomes.12 13

The dose–response relationship between the level of vicarious racism reported and child HCU is novel and should be understood with consideration of the patterning of racism in NZ society. Prior research has shown that Māori adults are almost 10 times more likely than Europeans to report multiple types of racism.31 We extend this by documenting a higher prevalence of multiple types of racism among Māori caregivers than European/Others. Furthermore, we show that Māori and Asian children are more likely to be exposed to multiple types of racism than European/Other children. Together, evidence suggests that Māori children will be disproportionately affected by the relationships between vicarious racism and low HCU.

Emergent research suggests that caregiver mental health problems and parenting stress are associated with lower preventive care and higher emergency department utilisation among their children,22–24 with explanations including inability to seek needed healthcare and negative attitudes towards the healthcare system (eg,32). We question the utility of this view for informing interventions to improve child HCU because they disregard the systems within which health services are configured and racism is constructed and maintained. It is possible that caregivers who experience racism and/or psychological distress might distrust systems of power or be reluctant to engage with health services, particularly if they have been a site of discrimination.33 However, our findings do not suggest greater health system disengagement, but instead show that caregivers who experience racism face difficulties obtaining care and are dissatisfied with the care their child receives. This aligns with findings from the NZ Youth Survey, which showed that Pacific youth (13–17 years) who reported experiences of unfair treatment by a health professional due to their ethnicity were three times more likely to report unmet need for care than those who did not.34 The findings highlight the extensive reach of racism into child HCU and suggest that interventions to improve child HCU require action targeted at the health system rather than caregivers.

Strengths of the study include the use of national survey data, large sample sizes and the use of meta-analytical techniques for associational models. Moreover, we have addressed gaps in the literature by documenting experiences of racism outside of the USA and among indigenous children.9 10 Estimation of prevalences for the major ethnic groupings in NZ is noteworthy. However, preaggregation of ethnicity data in 2011/2012 NZHS prevented separation of the ‘Other’ from the European grouping. Although using European/Other in analysis may have underestimated associations, the impact is likely small since this grouping largely consisted of Europeans. The cross-sectional study design hampered causal interpretations and prevented formal mediation analyses. Nonetheless, we identified potential variables for future exploration. To improve precision of estimates and generalisability, we prioritised variables that were available in both surveys and applicable across the entire age range (0–14 years). However, this approach restricted the outcome measures investigated. Future studies could investigate this relationship using other measures of child HCU, including in relation to specific types of healthcare (eg, oral healthcare). Low prevalence of unfair treatment by a health professional among caregivers prevented specific analysis of this racism measure (data not shown). However, racism more broadly has been linked to HCU in adults,35 including in NZ.36 Although the NZHS uses self-report measures, it provided a range of confounders and potential pathway variables for analysis. The negligible impact of caregiver SEP on the associations between vicarious racism and child HCU was unexpected. It is possible that controlling for ethnicity in an earlier step in our models captured some of this potential effect. Residual confounding may also be relevant with only two caregiver SEP measures available.

This study suggests that policy interventions and service improvements should be contextualised within the experiences of indigenous and ethnically minoritised families and target all forms of racism in society. Strengthening cultural competency of the child healthcare system and increasing diversity of the workforce is necessary.37 Training healthcare providers on issues of race/ethnicity and racism will be critical and beneficial, with a recent evaluation of antiracism training among child healthcare professionals in the UK showing this is well accepted and results in positive behaviour change (by health professionals).38 Findings highlight a need to better identify and provide support for mental health issues among caregivers of children, and that this must work for minoritised ethnic groups who appear to be at higher risk.

Vicarious racism may be an important determinant of ethnic inequities in child HCU. That up to one-third of indigenous Māori children were exposed to vicarious racism is a significant breach of their indigenous rights to be free from discrimination. We challenge the view that low child HCU reflects poor parenting,24 and instead argue for interventions that target all forms of racism in society.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participants of all surveys used in this paper, and Statistics New Zealand and the Ministry of Health for assisting with data access. Thanks also to Ruruhira Rameka for administrative support and our external advisors for their advice on the wider project.

Footnotes

Contributors: DC and RH are the principal investigators of this research and led the conceptualisation of this study. S-JP conducted the analysis, led the literature review and was responsible for writing the first draft of the manuscript. JS supervised the analysis and undertook the meta-analysis. All authors contributed to the development of the study design and analytical plan, interpretation of findings and revisions of the manuscript, and approved the final version.

Funding: This research is funded by the New Zealand Ministry of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval for this analysis was granted by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (Health, reference: HD16/006).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Access to the data used in this study was provided by Statistics New Zealand under conditions designed to keep individual information secure in accordance with the requirements of the Statistics Act 1975.

References

- 1. United Nations General Assembly. Convention on the Rights of the Child. New York, NY: United Nations, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Flores G, Lin H. Trends in racial/ethnic disparities in medical and oral health, access to care, and use of services in US children: has anything changed over the years? Int J Equity Health 2013;12:10 10.1186/1475-9276-12-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ou L, Chen J, Hillman K, et al. The comparison of health status and health services utilisation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous infants in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2010;34:50–6. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00473.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brandon AD, Costanian C, El Sayed MF, et al. Factors associated with difficulty accessing health care for infants in Canada: mothers' reports from the cross-sectional Maternity Experiences Survey. BMC Pediatr 2016;16:192 10.1186/s12887-016-0733-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ellison-Loschmann L, Pearce N. Improving access to health care among New Zealand’s Maori population. Am J Public Health 2006;96:612–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Health Utilisation Research Alliance (HURA). Ethnicity, socioeconomic deprivation and consultation rates in New Zealand general practice. J Health Serv Res Policy 2006;11:141-9 10.1258/135581906777641721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministry of Health. Annual Update of Key Results 2015/16: New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ministry of Health. The Health of Māori Adults and Children, 2011–2013. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Priest N, Paradies Y, Trenerry B, et al. A systematic review of studies examining the relationship between reported racism and health and wellbeing for children and young people. Soc Sci Med 2013;95:115–27. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heard-Garris NJ, Cale M, Camaj L, et al. Transmitting Trauma: A systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Soc Sci Med 2018;199:230–40. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kelly Y, Becares L, Nazroo J. Associations between maternal experiences of racism and early child health and development: findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2013;67:35–41. 10.1136/jech-2011-200814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bécares L, Nazroo J, Kelly Y. A longitudinal examination of maternal, family, and area-level experiences of racism on children’s socioemotional development: Patterns and possible explanations. Soc Sci Med 2015;142:128–35. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Priest N, Paradies Y, Stevens M, et al. Exploring relationships between racism, housing and child illness in remote indigenous communities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:440–7. 10.1136/jech.2010.117366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hobbs MR, Morton SM, Atatoa-Carr P, et al. Ethnic disparities in infectious disease hospitalisations in the first year of life in New Zealand. J Paediatr Child Health 2017;53:223–31. 10.1111/jpc.13377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mansouri F, Jenkins L. Schools as sites of race relations and intercultural tension. Austr J Teach Educ 2010;35:93–108. 10.14221/ajte.2010v35n7.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: implications for the well-being of people of color. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2000;70:42–57. 10.1037/h0087722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Priest N, Perry R, Ferdinand A, et al. Experiences of racism, racial/ethnic attitudes, motivated fairness and mental health outcomes among primary and secondary school students. J Youth Adolesc 2014;43:1672–87. 10.1007/s10964-014-0140-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Children’s Health, the Nation’s Wealth: Assessing and Improving Child Health. Washington, DC: Committee on Evaluation of Children’s Health. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, et al. Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1186:69–101. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Filc D, Davidovich N, Novack L, et al. Is socioeconomic status associated with utilization of health care services in a single-payer universal health care system? Int J Equity Health 2014;13:115 10.1186/s12939-014-0115-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0138511 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sills MR, Shetterly S, Xu S, et al. Association between parental depression and children’s health care use. Pediatrics 2007;119:e829–e836. 10.1542/peds.2006-2399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Minkovitz CS, Strobino D, Scharfstein D, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and children’s receipt of health care in the first 3 years of life. Pediatrics 2005;115:306–14. 10.1542/peds.2004-0341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Serbin LA, Hubert M, Hastings PD, et al. The influence of parenting on early childhood health and health care utilization. J Pediatr Psychol 2014;39:1161–74. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ministry of Health. New Zealand Health Survey Methodology Report. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ministry of Health. Methodology Report for the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harris R, Tobias M, Jeffreys M, et al. Racism and health: the relationship between experience of racial discrimination and health in New Zealand. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1428–41. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ministry of Health. Ethnicity Data Protocols for the Health and Disability Sector. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Salmond C, Crampton P, Atkinson J. NZDep2006 Index of Deprivation. Wellington: Department of Public Health, University of Otago, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 2002;32:959–76. 10.1017/S0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harris R, Tobias M, Jeffreys M, et al. Effects of self-reported racial discrimination and deprivation on Māori health and inequalities in New Zealand: cross-sectional study. Lancet 2006;367:2005–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68890-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Raphael JL, Zhang Y, Liu H, et al. Parenting stress in US families: implications for paediatric healthcare utilization. Child Care Health Dev 2010;36:216–24. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01052.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Auslander WF, Thompson SJ, Dreitzer D, et al. Mothers' satisfaction with medical care: perceptions of racism, family stress, and medical outcomes in children with diabetes. Health Soc Work 1997;22:190–9. 10.1093/hsw/22.3.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Teevale T, Denny S, Percival T, et al. Pacific secondary school students' access to primary health care in New Zealand. N Z Med J 2013;126:58-68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burgess DJ, Ding Y, Hargreaves M, et al. The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2008;911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harris R, Cormack D, Tobias M, et al. Self-reported experience of racial discrimination and health care use in New Zealand: results from the 2006/07 New Zealand Health Survey. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1012–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C. The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff 2002;21:90–102. 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Webb E, Sergison M. Evaluation of cultural competence and antiracism training in child health services. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:291–4. 10.1136/adc.88.4.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

archdischild-2017-313866supp001.docx (18.3KB, docx)

archdischild-2017-313866supp002.docx (38.8KB, docx)