Abstract

Objective

Trials of ginkgo biloba extract (GBE) for the prevention of acute mountain sickness (AMS) have been published since 1996. Because of their conflicting results, the efficacy of GBE remains unclear. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess whether GBE prevents AMS.

Methods

The Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Google Scholar and PubMed databases were searched for articles published up to 20 May 2017. Only randomised controlled trials were included. AMS was defined as an Environmental Symptom Questionnaire Acute Mountain Sickness-Cerebral score ≥0.7 or Lake Louise Score ≥3 with headache. The main outcome measure was the relative risk (RR) of AMS in participants receiving GBE for prophylaxis. Meta-analyses were conducted using random-effects models. Sensitivity analyses, subgroup analyses and tests for publication bias were conducted.

Results

Seven study groups in six published articles met all eligibility criteria, including the article published by Leadbetter et al, where two randomised controlled trials were conducted. Overall, 451 participants were enrolled. In the primary meta-analysis of all seven study groups, GBE showed trend of AMS prophylaxis, but it is not statistically significant (RR=0.68; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.04; p=0.08). The I2 statistic was 58.7% (p=0.02), indicating substantial heterogeneity. The pooled risk difference (RD) revealed a significant risk reduction in participants who use GBE (RD=−25%; 95% CI, from a reduction of 45% to 6%; p=0.011) The results of subgroup analyses of studies with low risk of bias, low starting altitude (<2500 m), number of treatment days before ascending and dosage of GBE are not statistically significant.

Conclusion

The currently available data suggest that although GBE may tend towards AMS prophylaxis, there are not enough data to show the statistically significant effect of GBE on preventing AMS. Further large randomised controlled studies are warranted.

Keywords: ginkgo biloba extract, acute mountain sickness, meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This meta-analysis is the first systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating ginkgo biloba extract as an acute mountain sickness prophylactic.

This meta-analysis was strengthened by a thorough quality assessment of each enrolled study and comprehensive subgroup analyses.

There is notable heterogeneity and the small number of studies limits the analyses, but heterogeneity decreased after excluding studies with high risk of bias.

Insufficient power may be an issue in this meta-analysis.

Further large randomised controlled studies are warranted.

Introduction

Background

Rapid ascent from low to high altitude (>2500 m above sea level) is often followed by headache, fatigue, shortness of breath, sleeplessness and anorexia, a symptom complex called acute mountain sickness (AMS).1 The Lake Louise Score (LLS) questionnaire2 and the Environmental Symptom Questionnaire III3 are two tools to diagnose and evaluate the severity of AMS. AMS is more likely to happen at altitudes higher than 2500 m,4 and worldwide studies reported an incidence of AMS of 25%–37% at 1900–3400 m.1 5 Children are more prone to develop AMS, with an incidence of 59%.6

The pathophysiology of AMS is associated with cerebral oedema, with the most compelling evidence coming from the brain MRI study of Hackett et al,7 which showed intense T2 signals in the white matter, particularly in the splenium and corpus callosum. Vasogenic leakage increases the permeability of the endothelium, causing an elevation in intravascular pressures and inducing hypoxaemia. In addition, hypoxic ventilatory response and activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system are also reported to be associated with AMS.8 The most effective method to prevent AMS is gradual ascent. The most common pharmacological agent used to prevent AMS is acetazolamide.9 However, acetazolamide can cause paresthesia, dysgeusia, and sometimes nausea or drowsiness.10 Its use is also contraindicated in patients with a history of anaphylaxis to sulfa antibiotics or acetazolamide.

Importance

Ginkgo biloba extract (GBE) is an option for those seeking a natural alternative treatment. GBE is found to decrease tissue hypoxia, induce vasodilation, and reduce free-radical production and lung leak, which may in turn prevent AMS.11–14 Roncin et al 15 in 1996 published the first study to suggest that GBE can prevent AMS. However, not all subsequent studies have shown benefit.13 16–20 To date, there is no best evidence to support the effectiveness of GBE.

Goal of this investigation

The aim of our study was to assess the effectiveness of GBE as prophylaxis for AMS by conducting a meta-analysis and systematic review of the relevant literature.

Methods

Databases and search strategy

We searched the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Google Scholar and PubMed databases for articles published up to 20 May 2017. No limits were applied to our Boolean search strategy, which included keywords (‘Ginkgo’, ‘Altitude Sickness’, ‘Mountain’), medical subject headings (‘Ginkgo biloba’, ‘Altitude Sickness’) and Emtree terms (‘Ginkgo biloba’, ‘altitude disease’). The full search strategy for database is provided in the online supplementary file. References from retrieved articles were also examined to identify other relevant articles.

bmjopen-2018-022005supp001.pdf (217.5KB, pdf)

Studies were included in the systematic review if they (1) were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of healthy non-acclimatised adult between the ages of 18 and 60 years; (2) compared GBE with placebo; (3) were conducted in humans; and (4) were studies that diagnosed AMS using the Lake Louise Score or the Environmental Symptom Questionnaire Acute Mountain Sickness-Cerebral score (AMS-C). We excluded studies with subjects who were pregnant and had symptoms consistent with AMS at baseline. Studies were also excluded if they were irrelevant to the aim of the study, were animal studies, lacked a placebo group, or were published as review articles, case reports, editorials or letters. The systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted under the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (see online online supplementary checklist).

bmjopen-2018-022005supp002.pdf (314.7KB, pdf)

Outcome measures

AMS was defined as an AMS-C score ≥0.7 or an LLS ≥3 with headache. The primary outcome was the relative risk (RR) of AMS in participants receiving GBE for prophylaxis. We only extracted data when they were available in dichotomous form. The secondary outcomes of the included studies are summarised in online supplementary table 1.

Data extraction and assessment of methodological quality

Two reviewers (T-YT and Y-CS) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all articles identified from the search strategy. Inter-reviewer disagreements concerning the inclusion or exclusion of a study were resolved by consensus and, if necessary, consultation with a third reviewer (S-HW).

The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool was used to assess the risk of selection, performance, detection, attrition and reporting biases in the included randomised trials.21 We defined studies as ‘high risk of bias’ if one or more key domains is taken as high risk in the checklist. All coauthors discussed and made the final decisions about the overall risk of bias in the included trials. If data were not readily available or clear, we contacted the first authors and the corresponding authors to get further information. If studies were found to be at high risk of bias, meta-analyses stratified by study quality were performed.

Both reviewers independently extracted data from the articles selected for inclusion. The extracted data included the name of the first author, year of publication, numbers of participants, gender, starting and final altitudes, AMS scoring definitions, prescriptions of GBE, days of treatment prior to ascent, and number of individuals with AMS in the treatment and control groups.

Data collection, data processing and primary data analysis

Pooled RRs with corresponding 95% CIs are derived for all studies and different subgroups of interest. The main outcome measure was the RR of AMS in participants receiving GBE for prophylaxis. Random-effect models with DerSimonian and Laird method were selected for these analyses. The pooled risk difference (RD) was also measured as the alternative outcome. The pooled RD is the difference between the observed risks (proportions of participants with AMS) in the two groups.

We conducted subgroup analyses based on the quality of studies, starting altitude, number of treatment days before ascending and dosage of GBE.22–24 Between-study heterogeneity was evaluated with the I2 statistic.25 The Egger regression asymmetry test and Begg adjusted rank correlation test were applied for assessment of potential publication bias.26 27 We also conducted sensitivity analysis to evaluate the influence of each study on the overall pooled estimate. In dealing with zero cells, we add 0.5 to all cells of the 2×2 table for the study. Analyses were all conducted using STATA V.11.0. All statistical tests were two-sided and were considered significant when the p value was 0.05 or less.

Patient and public involvement statement

Participants and the public sector were not directly involved in the design and conduct of this study.

Results

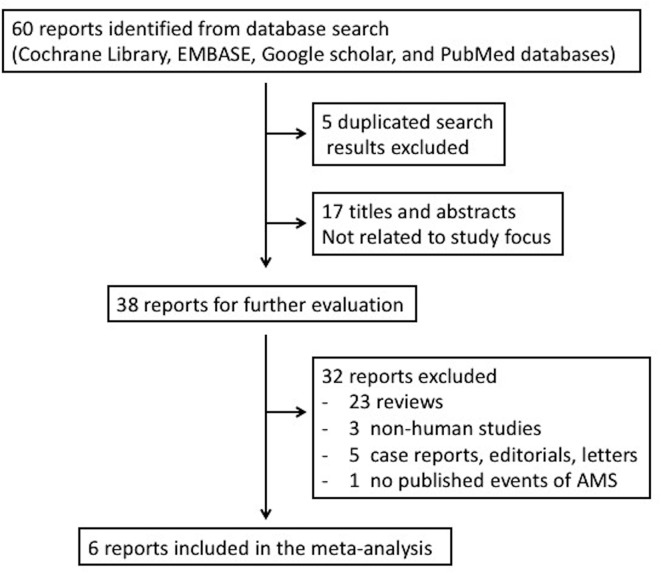

The literature search and study selection process are summarised in figure 1. After the exclusion of duplicate studies, non-relevant studies and other studies that met the exclusion criteria based on a screening of article titles and abstracts, 38 potentially relevant studies were retrieved for full review.

Figure 1.

Trial selection algorithm. AMS, acute mountain sickness.

One publication was retrieved by hand search of references. In this study, Wang et al 28 compared the prophylactic effect of GBE with that of other Chinese medications on AMS. However, the study had no placebo group design29 and had to be excluded from our meta-analysis.

In the randomised, double-blind study by Ke et al in 2013,20 AMS was reported as a secondary outcome and the number of events in each group was not reported. We contacted the first and corresponding authors by email but (as of 12 June 2018) received no response. Since the published data could not be included for analysis, we excluded this study.

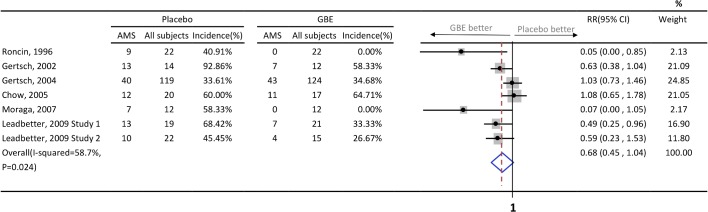

Six published articles met all eligibility criteria after a careful review process.13 15–19 In the article published by Leadbetter et al,19 two RCTs were conducted. As a result, a total of 7 study groups with 451 participants were enrolled. The characteristics of these studies and the participants are listed in table 1. Four study groups13 15 16 19 demonstrated the efficacy of GBE in preventing AMS, while three17–19 did not. All studies had small numbers of subjects except the one by Gertsch and colleagues.17 Of note, participants in the study conducted by Gertsch et al 17 published in 2004 started GBE treatment at high altitude (4280–4358 m), which was different from the other studies. Further information such as study dosage, prescription frequency, number of days prior to ascending and source of GBE is summarised in table 2. The number of AMS events and its incidence is summarised in figure 2. The quality of evidence of these studies as assessed by Cochrane Collaboration’s tool is presented in table 3. Two of six articles were not double-blinded and both of them included male participants only.13 15 The study conducted by Gertsch et al 16 in 2002 used ‘first-come first-served basis’ after receiving signed consent. Therefore, we judge it as ‘unclear random-sequence generation’. In addition, we appraised it as incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) because the study presented data on only 26 subjects when the intention was to enrol 100 subjects.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Participants (n) | Male (%) | Starting altitude (m) | Altitude reached (m) | Ascent rate (m/hour) | AMS definition | |

| Roncin et al,15 1996 | 44 | 100 | 1800 | 5400 | 15 | AMS-C>0.7 |

| Gertsch et al, 16 2002 | 26 | 46 | 0 | 4205 | 1402 | LLS≥3 with HA |

| Gertsch et al, 17 2004 | 243 | 70 | 4280–4358 | 4928 | 10–20 | LLS≥3 with HA |

| Chow et al,18 2005 | 37 | 54 | 1230 | 3800 | 1285 | LLS≥3 with HA |

| Moraga et al,13 2007 | 24 | 100 | 0 | 3696 | 435 | LLS≥3 or one symptom score ≥3 |

| Leadbetter et al,19

2009 study 1 |

40 | 45 | 2000 | 4300 | 1150 | AMS-C≥0.7 + LLS≥3 with HA |

| Leadbetter et al,19

2009 study 2 |

37 | 44 | 2000 | 4300 | 1150 | AMS-C≥0.7 + LLS≥3 with HA |

AMS, acute mountain sickness; AMS-C, the Environmental Symptom Questionnaire III Acute Mountain Sickness-Cerebral score; HA, headache; LLS, Lake Louise Score.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies, sources, dosage and duration of ginkgo biloba

| Ginkgo biloba extract source | Dose | Days of treatment prior to ascent | |

| Roncin et al,15 1996 | Tanakan DCI: EGb 761, Ipsen, Paris, France | 60 mg twice daily | 0 |

| Gertsch et al,16 2002 | GK501 Memfit, EGb 761, Pharmaton | 60 mg three times a day | 1 |

| Gertsch et al,17 2004 | GK501 International, Pharmaton | 120 mg twice daily | 1–2 |

| Chow et al,18 2005 | Ginkgo biloba 120 mg, Vegetarian NOW Foods | 120 mg twice daily | 5 |

| Moraga et al,13 2007 | EGb 761 Rokan, Andromaco Laboratories, Chile | 80 mg twice daily | 1 |

| Leadbetter et al,19

2009, study 1 |

Spectrum Quality, Laboratories Products | 120 mg twice daily | 4 |

| Leadbetter et al,19

2009, study 2 |

Technical Sourcing | 120 mg twice daily | 3 |

Figure 2.

Events of acute mountain sickness between placebo and GBE, and forest plot of meta-analysis. AMS, acute mountain sickness; GBE, ginkgo biloba extract; RR, relative risk.

Table 3.

Risk of bias in included studies

| Risk of bias domain | Roncin et al,15 1996 | Gertsch et al,16 2002 | Gertsch et al,17 2004 | Chow et al,18 2005 | Moraga et al,13 2007 | Leadbetter et al,19 2009 |

| Random-sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Blinding of participants (performance bias) | High | Low | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | High | Low | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | High | High | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Other source of bias | High | Low | High | Low | High | Low |

| Overall risk of bias | High | High | Low | Low | High | Low |

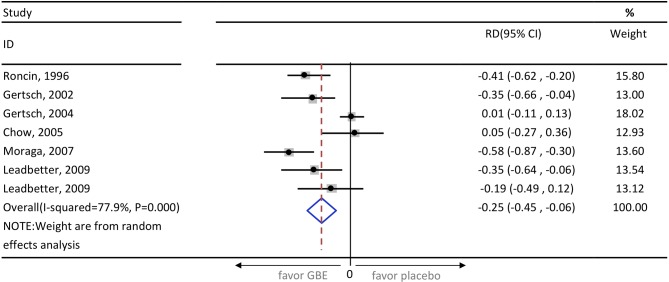

In the primary meta-analysis of all seven study groups, GBE showed trend of AMS prophylaxis, but it is not statistically significant (RR=0.68; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.04; p=0.08) (figure 2). The I2 statistic was 58.7% (p=0.02), indicating substantial heterogeneity. The pooled RD revealed a significant risk reduction in participants who use GBE (RD=−25%; 95% CI, from a reduction of 45% to 6%; p<0.001) (figure 3). After excluding three high-risk bias studies,13 15 16 the I2 statistic became 40.2% (p=0.17) and the result did not change (RR=0.84; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.21; p=0.36). In the same subgroup the pooled RD is also not statistically significant (RD=−9.7%; 95% CI, from a reduction of 27.4% to 7.9%; p=0.28). The Egger’s test and Begg’s test (p=0.22 and p=0.31, respectively) indicate the absence of statistical evidence of publication bias after excluding our presumed high-risk bias articles.

Figure 3.

Pooled risk difference of enrolled studies. GBE, ginkgo biloba extract; RD, risk difference.

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by removing one trial at a time to determine what influence each study had on the pooled analysis. The pooled result seemed to be robust. For example, removing the study conducted by Leadbetter et al in 200919 only changed the pooled estimate from 0.68 to 0.74 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.16; p=0.19; see online supplementary figure 1).

bmjopen-2018-022005supp003.jpg (225.6KB, jpg)

The results of several preplanned subgroup analyses were similar. Excluding the study by Gertsch and colleagues in 2004,17 GBE was not prophylactic when the starting altitude was below 2500 m (RR=0.56; 95% CI 0.31 to 1.01).13 15 16 18 19 Regarding the number of treatment days before ascending, GBE was not prophylactic when given ‘3–5 days prior to ascent’18 19 (RR=0.72; 95% CI 0.41 to 1.26) or ‘0–2 days prior to ascent’13 15–17 (RR=0.56; 95% CI 0.25 to 1.25). Dosage of GBE was also not prophylactic for AMS when given ‘less than 200 mg per day’13 15 16 (RR=0.16; 95% CI 0.01 to 2.57) or ‘more than 200 mg per day’17–19 (RR=0.84; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.21). Data on the number of participants and enrolled studies in each subgroup are summarised in online supplementary table 2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of RCTs evaluating GBE as an AMS prophylactic. In pooled analyses, we found that although GBE may tend towards AMS prophylaxis, it had no statistically significant prophylactic effect (RR=0.68; 95% CI 0.45 to 1.04; p=0.08). The results of several subgroup analyses were similar. GBE also failed to show benefits in preventing AMS in low-risk bias studies, studies in which the starting altitude was low, studies differing in the initial treatment regimen prior to ascent and different dosage of GBE.

The effectiveness of GBE in AMS prophylaxis has been reported.13 15 16 19 Zhang and colleagues29 in 2003 reported that GBE was the most effective of six Chinese medicines tested for AMS prophylaxis. GBE has been used primarily for the treatment of dementias (eg, Alzheimer’s disease), peripheral vascular diseases (eg, intermittent claudication) and neurosensory problems (eg, tinnitus).30 Hypotheses have been proposed to explain the possible role that GBE plays in preventing AMS. Hypoxia is a common feature of AMS. Several studies have suggested that nitric oxide (NO) may play a pathogenic role in AMS by mediating hypoxia-induced cerebral vasodilation in humans.11–13 GBE was found to be an NO scavenger. NO scavenging can result in decreased intracellular NO level.14 Furthermore, GBE may inhibit phosphodiesterase activity, thus enhancing relaxation of parietal smooth muscle cells and so lead to vasodilation of parietal vessels. Vasodilation in turn increases tissue perfusion and decreases local hypoxia.14 Other potential mechanisms include increasing endogenous antioxidants,31 reducing free-radical production32 and reducing lung leak during hypoxia.33 GBE was also shown to prevent high-altitude pulmonary oedema in a rat model.34

On the other hand, several studies failed to demonstrate the benefit of GBE in AMS prophylaxis.17 18 20 The duration of therapy before ascent, dosage of GBE and differences in the altitude at which GBE is initiated may account for the conflicts between trial results. To test these hypotheses, we conducted subgroup analyses and obtained similar results to those obtained with the original pooled data. Another explanation for the differences in efficacy may be variation in the GBE composition. For instance, Leadbetter and colleagues19 in 2009 compared GBE from two different sources and found they differed in composition as well as ability to reduce the incidence and severity of AMS following rapid ascent to high altitude. The German Federal Institute for Drugs and Medicinal Devices Commission E recommends similar specifications for standardisation of GBE. All included studies used GBE that met the German E commission standard, but most of the studies use products from different companies. As an herbal supplement, more than 60% of GBE component is not mandated by law and composition may vary considerably between manufacturers. A lack of bioequivalence has been noted between brands of GBE.35 36

Limitations

Our systematic review has several limitations. First, to limit the influence of study biases on pooled evaluation, we decided to only include RCTs. However, there were few RCTs in this field. Moreover, only four of six RCTs were double-blinded. Second, because of the difficulty in carrying out high-altitude medicine studies, many studies involved only a small number of cases. In our primary pooled analysis, a total of 451 participants were enrolled. Insufficient power may be an issue in this meta-analysis. There are not enough data to show the statistically significant effect of GBE on preventing AMS, and further studies are warranted. Third, the participants were predominantly adult men, and whether there is gender or age difference between treatment (GBE vs placebo) groups or response (no AMS vs AMS) groups is unknown. Fourth, GBE is a complex mixture of natural components. It is difficult to standardise all components. A lack of consistency between commercially available GBE preparations may explain these differing results. Finally, differences between studies in factors such as the strength, rate of ascent and other characteristics of participants may also account for inconsistent results.

Conclusion

The currently available data suggest that although GBE may tend towards AMS prophylaxis, there are not enough data to show the statistically significant effect of GBE on preventing AMS. Further large randomised control studies are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: T-YT analysed and interpreted the data and was a major contributor to writing the manuscript. S-HW interpreted the data. Y-KL supervised the study and interpreted the data. Y-CS interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, Taiwan, approved the protocol.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad Data Repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.35h13bg.

References

- 1. Honigman B, Theis MK, Koziol-McLain J, et al. . Acute mountain sickness in a general tourist population at moderate altitudes. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:587–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roach RC BP, Hackett PH, Oelz O. The Lake Louise acute mountain sickness scoring system : Sutton JR, Coates G, Huston CS, Hypoxia and molecular medicine: proceedings of the 8th international hypoxia symposium. Lake Louise, Alberta, Canada. Burlington, VT: Queen City Printer, 1993:272–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sampson JB, Cymerman A, Burse RL, et al. . Procedures for the measurement of acute mountain sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med 1983;54(12 Pt 1):1063–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Basnyat B, Murdoch DR. High-altitude illness. Lancet 2003;361:1967–74. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13591-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang SH, Chen YC, Kao WF, et al. . Epidemiology of acute mountain sickness on Jade Mountain, Taiwan: an annual prospective observational study. High Alt Med Biol 2010;11:43–9. 10.1089/ham.2009.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan CW, Lin YC, Chiu YH, et al. . Incidence and risk factors associated with acute mountain sickness in children trekking on Jade Mountain, Taiwan. J Travel Med 2016;23:tav008 10.1093/jtm/tav008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hackett PH, Yarnell PR, Hill R, et al. . High-altitude cerebral edema evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging: clinical correlation and pathophysiology. JAMA 1998;280:1920–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schoene RB. Illnesses at high altitude. Chest 2008;134:402–16. 10.1378/chest.07-0561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zafren K. Prevention of high altitude illness. Travel Med Infect Dis 2014;12:29–39. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seupaul RA, Welch JL, Malka ST, et al. . Pharmacologic prophylaxis for acute mountain sickness: a systematic shortcut review. Ann Emerg Med 2012;59:307–17. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roach RC, Hackett PH. Frontiers of hypoxia research: acute mountain sickness. J Exp Biol 2001;204(Pt 18):3161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Mil AH, Spilt A, Van Buchem MA, et al. . Nitric oxide mediates hypoxia-induced cerebral vasodilation in humans. J Appl Physiol 2002;92:962–6. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00616.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moraga FA, Flores A, Serra J, et al. . Ginkgo biloba decreases acute mountain sickness in people ascending to high altitude at Ollagüe (3696 m) in northern Chile. Wilderness Environ Med 2007;18:251–7. 10.1580/06-WEME-OR-062R2.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marcocci L, Maguire JJ, Droy-Lefaix MT, et al. . The nitric oxide-scavenging properties of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1994;201:748–55. 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roncin JP, Schwartz F, D’Arbigny P. EGb 761 in control of acute mountain sickness and vascular reactivity to cold exposure. Aviat Space Environ Med 1996;67:445–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gertsch JH, Seto TB, Mor J, et al. . Ginkgo biloba for the prevention of severe acute mountain sickness (AMS) starting one day before rapid ascent. High Alt Med Biol 2002;3:29–37. 10.1089/152702902753639522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gertsch JH, Basnyat B, Johnson EW, et al. . Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled comparison of ginkgo biloba and acetazolamide for prevention of acute mountain sickness among Himalayan trekkers: the prevention of high altitude illness trial (PHAIT). BMJ 2004;328:797 10.1136/bmj.38043.501690.7C [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chow T, Browne V, Heileson HL, et al. . Ginkgo biloba and acetazolamide prophylaxis for acute mountain sickness: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:296–301. 10.1001/archinte.165.3.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leadbetter G, Keyes LE, Maakestad KM, et al. . Ginkgo biloba does–and does not–prevent acute mountain sickness. Wilderness Environ Med 2009;20:66–71. 10.1580/08-WEME-BR-247.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ke T, Wang J, Swenson ER, et al. . Effect of acetazolamide and gingko biloba on the human pulmonary vascular response to an acute altitude ascent. High Alt Med Biol 2013;14:162–7. 10.1089/ham.2012.1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. . The cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hackett PH, Roach RC, Illness H-A. New England Journal of Medicine 2001;345:107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Patot MC, Keyes LE, Leadbetter G, et al. . Ginkgo biloba for prevention of acute mountain sickness: does it work? High Alt Med Biol 2009;10:33–43. 10.1089/ham.2008.1085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dumont L, Mardirosoff C, Tramèr MR. Efficacy and harm of pharmacological prevention of acute mountain sickness: quantitative systematic review. BMJ 2000;321:267–72. 10.1136/bmj.321.7256.267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang J, Xiong X, Xing Y, et al. . Chinese herbal medicine for acute mountain sickness: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:1–8. 10.1155/2013/732562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang HJY XZ, Ha ZD. Role of six different medicines in the symptomatic scores of benign form of acute mountain sickness. Medical Journal of National Defending Forces in Northwest China 2003;24:341–3. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sierpina VS, Wollschlaeger B, Blumenthal M. Ginkgo biloba. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:923–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Louajri A, Harraga S, Godot V, et al. . The effect of ginkgo biloba extract on free radical production in hypoxic rats. Biol Pharm Bull 2001;24:710–2. 10.1248/bpb.24.710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naik SR, Pilgaonkar VW, Panda VS. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of Ginkgo biloba phytosomes in rat brain. Phytother Res 2006;20:1013–6. 10.1002/ptr.1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu KX, Wu WK, He W, et al. . Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) attenuates lung injury induced by intestinal ischemia/reperfusion in rats: roles of oxidative stress and nitric oxide. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:299–305. 10.3748/wjg.v13.i2.299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berg JT. Ginkgo biloba extract prevents high altitude pulmonary edema in rats. High Alt Med Biol 2004;5:429–34. 10.1089/ham.2004.5.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. De Smet PA. Herbal remedies. N Engl J Med 2002;347:2046–56. 10.1056/NEJMra020398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kressmann S, Müller WE, Blume HH. Pharmaceutical quality of different Ginkgo biloba brands. J Pharm Pharmacol 2002;54:661–9. 10.1211/0022357021778970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022005supp001.pdf (217.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022005supp002.pdf (314.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022005supp003.jpg (225.6KB, jpg)