Abstract

Background

Previous studies have identified issues with the doctor–patient relationship in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) that negatively impact symptom management. Despite this, little research has explored interactions between GPs and patients with refractory IBS. National guidelines suggest cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as a treatment option for refractory symptoms.

Aim

To explore perceptions of interactions with GPs in individuals with refractory IBS after receiving CBT for IBS or treatment as usual (TAU).

Design and setting

This qualitative study was embedded within a trial assessing CBT in refractory IBS. Fifty-two participants took part in semi-structured interviews post-treatment in UK primary and secondary care.

Method

Inductive and/or data-driven thematic analysis was conducted to identify themes in the interview data.

Results

Two key themes were identified: perceived paucity of GPs’ IBS knowledge and lack of empathy from GPs, but with acknowledgement that this has improved in recent years. These perceptions were described through three main stages of care: reaching a ‘last-resort diagnosis’; searching for the right treatment through a trial-and-error process, which lacked patient involvement; and unsatisfactory long-term management. Only CBT participants reported a shared responsibility with their doctors concerning symptom management and an intention to reduce health-seeking behaviour.

Conclusion

In this refractory IBS group, specific doctor–patient communication issues were identified. Increased explanation of the process of reaching a positive diagnosis, more involvement of patients in treatment options (including a realistic appraisal of potential benefit), and further validation of symptoms could help. This study supports a role for CBT-based IBS self-management programmes to help address these areas and a suggestion that earlier access to these programmes may be beneficial.

Keywords: cognitive behavioural therapy, doctor–patient relations, irritable bowel syndrome, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic and relapsing disorder of the gastrointestinal tract characterised by abdominal pain, bloating, and changes in bowel habit. IBS is not explained by an organic abnormality and it is defined as a functional disorder: a disorder of the gut–brain interaction. IBS affects between 10–25% of individuals in community samples and approximately 11% of the global population.1,2 The national annual projected costs for treating patients with IBS in the UK range from 45.6 million GBP to 200 million GBP.3

Current diagnostic criteria4 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines 5 encourage:

a positive diagnosis of IBS, minimising the need for unnecessary investigations after assessing ‘red flag’ symptoms and relevant blood test results;

treatment concentrated in primary care, referring patients into secondary care only if ‘red flags’ are identified; and

cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or psychotherapy for those patients who do not respond to medications and dietary/lifestyle advice after 12 months.

CBT has been shown to decrease IBS symptom severity, improve quality of life, and promote patients’ ability to cope with their illness.6,7 Previous qualitative studies have identified issues with the doctor–patient relationship, with patients perceiving doctors to show a lack of empathy during IBS-related consultations, dismiss or undervalue IBS symptoms, and provide insufficient information about the nature of the condition and symptom management.8–11 Patients from the UK described the diagnostic process as confusing and the lengthy search for successful medications as frustrating, affecting their trust in the NHS.12,13

Though previous studies have interviewed long-term sufferers,12,13 little research has explored specifically the interactions between primary care doctors and individuals with refractory IBS (defined as ongoing symptoms after 12 months despite being offered appropriate medications and lifestyle advice). Patients with ongoing symptoms may vary in severity and beliefs, and are worthy of study. These patients can represent a particular challenge for doctors due to their poor response to treatments and frequent use of healthcare services.14 Therefore, the identification of aspects that either promote or hinder these interactions can provide useful resources to help GPs communicate more effectively.

As described, the available body of literature highlights insufficient person-centred care during IBS consultations. In contrast with this, CBT for IBS is based on an individual conceptualisation of patient problems aimed to improve self-management of physical symptoms and stress, and to promote a healthy lifestyle.15 Thus, exploring if CBT for IBS affects the attitudes of patients towards their GPs will generate insight into whether this approach has an impact on interactions with doctors in the context of managing refractory IBS.

How this fits in

Issues with the doctor–patient relationship in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) impact symptom management and prognosis. Despite this, little research has explored the interactions between GPs and patients with refractory IBS. These interactions can represent a particular challenge for doctors due to the poor response to treatment in refractory IBS. National guidelines suggest cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as a treatment option but current availability is limited. This study aimed to explore patients’ perceptions of interactions with their GPs after receiving either CBT for refractory IBS or usual care. A greater understanding of these interactions could enhance communication and generate insights into effects of CBT on the doctor–patient relationship.

The current qualitative study was embedded within a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) — Assessing Cognitive behavioural Therapy in Irritable Bowel syndrome (ACTIB) — assessing the clinical and cost-effectiveness of CBT in refractory IBS.16 Participants were interviewed after having received one of three treatments: therapist-delivered CBT (TCBT) plus treatment as usual (TAU); web-based CBT self-management (WCBT) plus TAU; and TAU only. The aim of this nested study was to explore, through qualitative interviews, the perceptions that individuals with refractory IBS hold of interactions with their GPs and how they view the impact of these interactions, after receiving either CBT for their IBS or TAU.

METHOD

Design

In total, 558 participants were recruited into the broader RCT from primary and secondary care in the London and Southampton areas over a period of 23 months (for further details refer to main ACTIB study).16 Before entering the ACTIB trial,16 all participants completed an online consent form and agreed to be contacted regarding an interview at 3 months post-baseline (post-treatment) and another at 12 months. This current study included all 3-month interviews.

The topic guide was developed collaboratively by the research team and included open-ended questions to explore: participant experiences during the trial; participant experiences with past IBS treatments and the care received for their IBS; and participant emotional experiences (interview questions and prompts are available from the authors on request). Participants’ reports regarding their views of interactions with GPs emerged naturally while conducting the interviews because of the inductive nature of the analysis. Only data relevant to the current study aim were analysed for this article.

Participants and recruitment

The researchers approached 100 of the 558 participants sequentially via email in the ACTIB study. Out of 100 individuals invited, 52 agreed to take part; when one participant declined the invitation and/or did not respond, another person with similar characteristics was contacted to achieve a final sample with a mix of clinical and demographic variables (sex, age, ethnic background, geographical location, study arm, symptom severity, and recruitment site). Analysis of the interviews, participant selection, and data collection proceeded in an iterative process until data saturation was reached (no new themes emerged from the data and each theme was refined within a diverse sample).

Overall, 52 interviews were conducted by two members of the research team: 10 face-to-face and 42 over the phone, based on participants’ preferences. Data collection was carried out between September 2014 and July 2016. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber, and anonymised. Interviews lasted 23–116 minutes with a mean of 56 minutes.

Data analysis

An inductive and/or data-driven thematic analysis was conducted17–20 to identify themes in the data, rather than applying a pre-existing theoretical framework. Box 1 contains a detailed description of the analytical steps implemented.21–23 NVivo (version 11) was used to facilitate data management and increase the transparency of the findings.

Box 1. Summary of analytical stages.

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Familiarisation | The first step of the analysis involved familiarisation with the data by reading and re-reading the first interview transcripts and noting early ideas |

| Generating initial codes | Initial codes were developed in Microsoft Word based on a close reading of the first 15 transcripts. These codes were then collated and defined in the first draft of a table of inductive codes, which included: code label, description, positive examples, negative examples, exceptions/restrictions. This first draft was used separately by the first author and an independent researcher to code the first 15 transcripts and eight new transcripts. Coding was compared to clarify concepts. The second draft of the table of codes was applied separately by the first author and the independent researcher to seven new transcripts and minor amendments were implemented. The final table of codes was applied by the independent researcher to 41 transcripts and by the first author to the whole dataset using NVivo (version11) |

| Searching for themes | Final codes were collated into potential themes (broader and more abstract than codes) by undertaking interpretative data analysis |

| Reviewing themes | Themes were reviewed in relation to the codes and the entire dataset to ensure that the coding units within each theme were coherent and that the differences between each theme were clear |

| Defining and naming theme | Themes were refined and named in order to generate clear definitions for each one. Between-group comparisons were made using the matrix query function in NVivo (version 11) |

The researchers worked within a contextual constructionist epistemology, which sustains that individuals interpret the world within particular cultural values and meanings.24,25 Researchers following this epistemology ground the findings in the participants’ actual descriptions and triangulation is used to get a fuller picture to increase the validity of the analysis.26 In the current study, a combination of perspectives from different disciplines (such as medicine and health psychology) enriched the interpretation of the findings.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows that the three trial groups had a similar number of participants and comparable demographic and clinical variables. This mix of characteristics within each group and in the overall sample was achieved through purposive sampling. The baseline symptom severity mean scores, which incorporate pain, distension, bowel dysfunction, and quality of life and/or global wellbeing,27 show that on average participants had moderately severe IBS symptoms.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of each trial group and overall sample

| Demographic | TCBT plus TAU (N= 17) | WCBT plus TAU (N= 17) | TAU (N= 18) | Total sample (N= 52) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female, n (%) | 13 (76.5%) | 14 (82.4%) | 13 (72.2%) | 40 (76.9%) |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity, n | ||||

| White British | 11 | 12 | 15 | 38 |

| White other | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 |

| White Asian | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Black African | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Indian | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Irish | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Other | – | 1 | – | 1 |

|

| ||||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 39.94 (11.71) | 42.41 (17.37) | 39.72 (13.23) | 40.67 (14.06) |

|

| ||||

| IBS-SSS score, mean (SD) | 283.47 (117.11) | 259.65 (124.39) | 236.83 (86.36) | 259.54 (109.61) |

|

| ||||

| Recruitment site, n | ||||

| Primary care | 11 | 13 | 11 | 35 |

| Secondary care | 6 | 4 | 7 | 17 |

|

| ||||

| Duration of symptoms on entering the study, years, mean (SD) | 15.25 (7.3) | 15.52 (9.04) | 17.92 (12.89) | 16.26 (9.96) |

|

| ||||

| Length of IBS diagnosis on entering the study, years, mean (SD) | 7.94 (7.66) | 11.82 (9.22) | 11.33 (10.76) | 10.38 (9.31) |

IBS = irritable bowel syndrome. IBS-SSS = IBS Symptom Severity Score. TAU = treatment as usual. TCBT = therapist-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy. WCBT = web-based cognitive behavioural therapy.

There were no significant differences between those participants who took part in the qualitative interviews and those who did not respond. Demographic and clinical characteristics of those participants who took part in the qualitative interviews and those who declined and/or did not respond, as well as results of independent t-tests comparing demographics of interviewees and non-responders, are available from the authors on request.

Overall description of main themes and sub-themes

Frustration and helplessness were identified as the main emotional responses elicited by at least half of the interviewees. These emotions seemed to link to two key themes:

Perceived paucity of GPs’ knowledge of IBS and its treatment; and

Perceived lack of empathy and support from doctors.

The perceived paucity of GPs’ knowledge was described in the context of three main stages in participants’ experience of IBS:

reaching a diagnosis of IBS (IBS as a ‘last-resort diagnosis’, lack of informational support);

finding the right treatment, defined as an exhausting trial and error process lacking patient involvement and significant symptom improvement; and

long-term management, mainly focused on the notion that long-term sufferers know more about IBS than doctors, though they still need to receive reassurance.

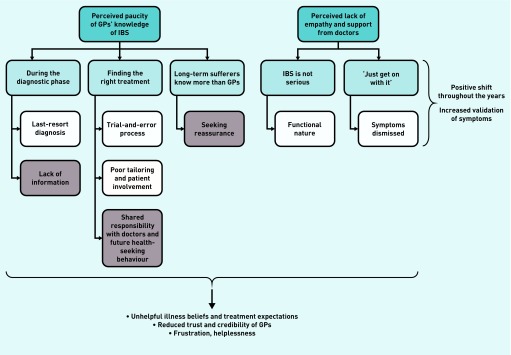

Differences between participants recruited from primary and secondary care were not identified. The themes and sub-themes are summarised in Figure 1 and are described in detail below, paying particular attention to the differences between the CBT and the TAU groups.

Figure 1.

Identified themes (dark blue) and sub-themes (lighter blue). Differences between cognitive behavioural therapy and treatment-as-usual participants were identified within the sub-themes associated with perceived paucity of GPs’ knowledge (main aspects highlighted in grey).

In all trial groups, the participants’ perceptions seem to be linked to negative emotions, illness beliefs and treatment expectations, and reduced trust in doctors. IBS = irritable bowel syndrome.

Theme 1: perceived paucity of GPs’ knowledge of IBS

Sub-theme 1a: During the diagnostic phase

a) ‘IBS is a last-resort diagnosis’. The fact that an IBS diagnosis was reached by the presence of specific physical symptoms, the assessment of red flags, and, in several cases, the exclusion of organic problems through diagnostic tests was often perceived by participants as the result of a lack of understanding of the real physical cause triggering their symptoms, a ‘last-resort diagnosis’.

Interestingly, patients were not aware that these steps, followed by many GPs, were necessary to reach a correct diagnosis, according to national guidelines, as illustrated by the following quotes:

‘Because I know that the doctors can’t find anything else wrong with you, so what they put on your results is IBS. And I find that really irritating that they sort of call it that as a last resort.’

(Patient [P] 38591,TAU, female [F], diagnosed in [D] 1999)

‘You’re in hospital, you’ve got a camera shoved up your bum and then the doctor says, “no, it’s just classic IBS symptoms”, then you kind of think that’s just a term they use when they haven’t got any other diagnosis.’

(P21339, WCBT, F, D 2008)

‘I had an endoscopy to check if I had Crohn’s disease and I didn’t. So they were pretty much like “well, there’s nothing particularly wrong with you”.’

(P20071, TAU, F, D 2009)

b) Lack of informational support. Interviewees from all groups felt that GPs provided little to no informational support after giving a diagnosis of IBS, often leading to a lack of acceptance of the received diagnosis:

‘I was just desperate […] I didn’t feel that I was getting enough support from actual GPs. I didn’t want to accept that I had IBS because my GP was telling me that I had IBS, but he actually failed to explain to me what it meant and how it would affect me.’

(P10074, WCBT, F, D 2013)

‘I haven’t had a lot of feedback from my doctor about it or advice from them […] You would be given a prescription at the doctor’s and you’re given, maybe, a bit of paper that tells you what it is, but that is it, you’ve got to go off yourself and do your own research to find out about it.’

(P21049, TAU, F, D 2011)

Box 2. Summary of findings and main group differences.

| Theme | Sub-theme | Common findings across groups | Differences across groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived paucity of GPs’ knowledge | 1a. During the diagnostic phase | IBS was perceived as a ‘last-resort diagnosis’ Poor informational support |

Only CBT participants talked about time constraints, preventing GPs from providing adequate information. Earlier access to CBT was suggested as a valuable support to GPs |

| 1b. Finding the right treatment | This stage was described as a ‘trial and error’ process lacking tailoring and patient involvement | Only CBT participants reported a shared responsibility with doctors concerning symptom management. Some CBT participants did not intend to return to their GP as they felt in control of their IBS |

|

| 1c. Long-term sufferers know more than doctors | Participants reported having more knowledge about IBS than doctors | Although TAU participants tended to report needing reassurance from doctors, CBT participants talked about receiving reassurance from their therapist or the content of the CBT programme | |

| 2. Perceived lack of empathy and support from doctors | 2a. ‘IBS is not serious’ | Participants reported a lack of empathy and support from GPs and consultants due to the functional nature of IBS | |

| 2b. ‘Just get on with your life’ | Participants reported that doctors told them at some point to ‘get on with their life’ and cope with their IBS | ||

| Some interviewees talked about a positive shift in doctors in recent years in terms of empathy and IBS awareness shown by doctors |

CBT = cognitive behavioural therapy. IBS = irritable bowel syndrome. TAU = treatment as usual.

CBT participants frequently reported how the information provided during therapy session(s) increased their understanding of IBS. Self-learning supported by the CBT programme appeared to promote an improved sense of control over symptoms (discussed in ‘Shared responsibility with doctors’ section below):

‘Every time I’ve been to the GP, he just says “oh you suffer from IBS”, but nothing explained. So reading the sessions […] has been really good because it removed that anxiety about IBS. It is completely new information that you read […] an alternative way to manage the symptoms.’

(P38910, TCBT, male [M], D 2010)

‘I found [CBT] helped me understand what’s going on, both from a physiological and psychological side of it, as well as dealing with the symptoms.’

(P25044, TCBT, F, D 2004)

Some CBT participants acknowledged that time constraints during GP consultations led to poor provision of informational support.

These interviewees suggested that offering patients earlier access to the CBT programme could actually help GPs to promote patient understanding about IBS and management options:

‘I don’t believe GPs have enough time to deal with the various issues that the study has addressed. I think that it should be an integral part of the service offered to patients with IBS.’

(P10074, WCBT, F, D 2013)

‘So everything that we worked through in the first section, I think it would be great if doctors could start sort of mentioning that. Or if there were guidance sheets on a website that you can look up. You could work through those sorts of things yourself.’

(P24547, TCBT, F, D 2005)

Sub-theme 1b: Finding the right treatment

a) ‘Trial and error process.’ Several participants reported anger or frustration when trying different unsuccessful treatments for their IBS, particularly soon after the diagnostic phase, describing this iterative phase as an exhausting ‘trial and error process’.

Frequently, this process was perceived as a result of lack of medical knowledge from their GP as opposed to a necessary transition phase to find the right fit for them. GPs did not seem to discuss the fact that there is no ‘one size fits all’ treatment:

‘I was actually expecting it to work; because it had been prescribed by the doctor I had assumed that they would know what they were prescribing me and that it should work […] I was quite livid […] I tried quite a few things, if the doctor can’t get it right — what hope have I got.’

(P20071, TAU, F, D 2009)

‘I think it’s a trial and error. From my experience of doctors, with IBS, they will prescribe you something, then that’s it […] Then you go back and you say it didn’t work, so they try something else.’

(P25119, TCBT, F, D 2014)

b) Poor tailoring and patient involvement. The absence of a tailored treatment seemed to have a detrimental effect on the active role of patients during this phase. Furthermore, participants often felt that GPs prescribed medications without sufficient explanation of how these might work:

‘If a GP doesn’t know how to deal with it and just sends me away, what am I supposed to do? It’s kind of like trying to drill down into what is for that person.’

(P45322, WCBT, F, D 2004)

‘A lot of doctors want to put you in one box and treat you for one specific thing, they don’t look at you as an individual, they say “oh, you take that medication”.’

(P45017, TAU, D 2007)

c) Shared responsibility with doctors. CBT seemed to promote a sense of shared responsibility with doctors in terms of their IBS management.

Specifically, CBT participants felt capable of coping with their IBS symptoms in a more independent way compared with individuals from the TAU group, who still relied on their doctors to look for ongoing solutions:

‘The next phase for me would be to go back to the doctor, see a different doctor to get a different take on it.’

(P29998, TAU, M, D 2014)

‘And I think the difference the CBT can make is that if we really learn to change our bad habits, it can be forever. We can control the problem always.’

(P40496, WCBT, F, D 2015)

‘You can go to the doctor, they could do lots of different things but at the end of the day, you’ve got to do it for yourself. That’s one thing that this study has actually made me do is I’ve been in control at all times. I’ve been able to take charge of my own learning.’

(P28570, WCBT, F, D 2002)

More importantly, a few participants explicitly reported that the CBT received during the trial had changed how frequently they intended to consult their GP. A sense of empowerment appeared to be the main reason underlying the patients’ intentions:

‘It’s a solution which is always in your mind and it will help cut the cost to the health service, which are too high, let’s face it. We’ve all got to do our bit to try not to go to the doctor’s so many times […] I revert to everything I’ve learnt, instead of going to the doctor.’

(P20822, TCBT, F, D 2013)

Sub-theme 1c: Long-term sufferers know more than doctors

Participants who labelled themselves ‘long-term sufferers’ usually expressed the belief that they had more knowledge about IBS symptoms and their management compared with GPs and consultants. Despite this perception, participants from the TAU group tended to report seeking reassurance from doctors, while CBT participants reported receiving reassurance when discussing their symptoms with a therapist or when reading the content of the programme:

‘I really lost total confidence with my first GP […] As a long-time sufferer with several GPs I’ve been through quite an exhaustive list of things that I can do […] often to the point where I feel I’ve known more about it than my doctors […] I’ve seen two consultants — it’s reaffirmed what I know.’

(P20774, TAU, M, D 1999)

‘And when I was saying to [therapist] about symptoms, he was sort of very reassuring.’

(P28849, WCBT, F, D 1987)

‘I think the CBT course can be quite reassuring; that’s why I’ve downloaded things.’

(P29023, WCBT, F, D 2000)

Theme 2: Perceived lack of empathy and support from doctors

Sub-themes 2a and 2b: ‘IBS is not serious’ and ‘Just get on with your life.’

Regardless of the length of the diagnosis, interviewees from all groups reported that GPs tended to embrace a dismissive and distant attitude during consultations due to the fact that IBS is a functional disorder and the poor understanding of the actual impact IBS has on patients’ quality of life:

‘I went to see my GP, they just dismissed all my symptoms and just said I just need to learn to live with it, get on with my life, even though it was like absolutely devastating, my whole life was like falling apart.’

(P40024, TAU, M, D 2013)

‘I think basically the biggest frustration was being [ignored] about your own symptoms — I mean it took a good 6 years to find a doctor that didn’t.’

(P33561, WCBT, F, D 2003)

Some long-term sufferers from all groups reported a positive shift in doctors in recent years in terms of the empathy shown during IBS consultations, as well as an increased validation of their symptoms:

‘I feel medical science is gaining awareness of it. Going back 10 years ago, I don’t think it was treated by GPs seriously at all.’

(P20774, TAU, M, D 1999)

‘My experience of GPs has been mixed. The first GP I went years ago didn’t seem to think it was that big an issue […] The most recent GP was very good and she was very sympathetic […]’

(P16045, TCBT, F, D 2003)

DISCUSSION

Summary

Two main themes emerged from exploring the views of patients with refractory IBS concerning communication issues: perceived paucity of GPs’ knowledge of IBS, and perceived lack of empathy and support from doctors. These negative perceptions seemed to be present during the entire patient journey and impacted on patients’ beliefs and expectations of their IBS and its treatment. Participants reported feeling frustration and helplessness as they neither understood their condition, nor experienced significant symptom relief.

Despite these negative experiences, participants from all groups recognised a positive shift in recent years in terms of empathy shown by doctors. Differences were identified between trial groups. Only CBT participants reported a shared sense of responsibility with doctors concerning symptom management. Some mentioned how CBT shaped their intention to reduce future healthcare seeking behaviour as they felt more capable of coping with their IBS. Only TAU participants tended to report needing reassurance from doctors. Participants from the CBT groups suggested that offering CBT self-management to patients with IBS sooner after the diagnosis could function as a valuable option for GPs to provide additional information regarding the condition and potential treatments, reassurance, and resources to self-manage symptoms.

Strengths and limitations

To the authors’ knowledge this is the first interview study using the largest sample of individuals with refractory IBS to explore perceptions of interactions with GPs. The systematic qualitative methodology in this study had strong purposive sampling, a robust audit trail, good coding rigour, and various perspectives in data interpretation. This rigorous analysis enhances validity and transferability of the findings.

It is worth noting that participants for this study had refractory IBS and had volunteered to take part in a CBT trial. Furthermore, participants were recruited from both primary and secondary care, and possibly differ from a pure GP population. This group of individuals with refractory IBS is important to study due to their ongoing symptoms and use of healthcare resources, but they may hold different views compared with patients with non-refractory IBS. Lastly, the sample was mostly composed of white British females, which resembles the sample recruited to the main trial.

Comparison with existing literature

The study’s findings resonate with previous qualitative research conducted with both individuals with IBS11, 28, 29 and GPs. Studies have found that most GPs who were interviewed conceive IBS as a diagnosis of exclusion (as opposed to a positive diagnosis) and that they infrequently ask their patients about their understanding and experiences of IBS.30–32 The present findings expanded on prior research by:

providing insight into the elements that contribute to the negative perceptions individuals with refractory IBS hold of their interactions with their GPs, particularly in terms of GPs’ knowledge of IBS;

demonstrating understanding of how these perceptions are shaped during each stage of care; and

exploring how CBT focused on self-management for IBS can affect the attitudes towards GPs.

Overall, participants in the present study seemed to have a pessimistic view of their GP relationship,13, 33 which may be related to the refractory nature of their IBS. For instance, interviewees perceived IBS as a ‘last-resort diagnosis’. This highlights the importance of providing feedback and the need to create a clear explanation of IBS at the early stage of care. Indeed, research suggests that GPs’ credibility increases when they create an explanatory framework for the condition that legitimises the symptoms.34 However, in the case of functional problems, doctors tend to either classify the symptoms as psychological in nature or ignore them.35, 36

Similar to individuals with chronic low-back pain,37 participants in this study reported that lack of information sharing occurred during both the diagnostic phase and the lengthy trial-and-error treatments process, which seemed to create unrealistic expectations of treatments and to reduce trust in doctors. A systematic review on the management of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care concluded that validating symptoms and explaining potential treatments can have a significant positive impact on the way patients understand and accept their condition, as well as their trust in GPs.38 However, the reality of time-pressured consultations may not allow GPs to cover all these aspects adequately.

Based on the accounts of interviewees in the present study, CBT-based self-management programmes could be a valuable resource to support GPs at all stages of the patient journey. Offering access to CBT soon after diagnosis could help to create a biopsychosocial conceptualisation of IBS, promote acceptance of the condition, and shape realistic appraisals concerning IBS treatments and the importance of self-management. Moreover, enhancing patient insight into how IBS is diagnosed and the fact that there is no ‘one size fits all’ treatment can reduce frustration towards doctors and positively influence the common perception of GPs’ paucity of IBS knowledge. In support of offering early access to CBT, an RCT testing a CBT-based self-management programme in individuals recently diagnosed with IBS in primary care found that this approach promoted a significant relief from symptoms up to 6 months post-treatment when compared with TAU.39

Participants in the current study reported the usefulness of CBT in providing reassurance and promoting a sense of shared responsibility with doctors regarding the management of IBS symptoms. Reassurance did not only come from talking to a therapist but also from reading the content of the CBT-based programme. Cognitive reassurance, which includes explanations and education, has been associated with higher patient satisfaction, enablement, and reduced concerns in primary care patients.40 Furthermore, the present participants’ reports highlighted the potential role of self-management interventions in reducing health-seeking behaviour. In line with this promising finding, a RCT with 420 patients with IBS recruited from primary care found that a self-help guidebook reduced primary care consultations by 60% at 1 year.41 This suggests that earlier access to self-management programmes can have promising clinical implications in primary care management of IBS, both for patients and doctors.

Implications for research and practice

The current study highlights specific areas associated with each step of care perceived by patients as problematic. Framing realistic beliefs about IBS and its treatment could increase trust in doctors and potentially reduce GP consultations.42 Providing more information to patients on the process of diagnosing IBS; presenting IBS as a positive diagnosis (including an explanatory model for their symptoms); involving patients in potential treatment options (including a realistic appraisal of potential benefit); and acknowledging the impact of IBS symptoms on patients’ lives appear to be key. A joint approach integrating GP advice and CBT self-management programmes for IBS may be a promising solution that is able to target these areas and mitigate some of the difficulties of providing this support during short GP consultations.

The efficacy of CBT interventions could be enhanced by including detailed information about how IBS is diagnosed and the lengthy trial-and-error process involved with searching for the right treatment(s). In turn, this may help to reframe the negative perceptions and attitudes towards GPs and potentially promote more collaborative doctor–IBS patient interactions. Further studies are needed to assess the role of CBT as an early intervention in IBS and its effects on doctor–patient interactions.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all the participants who took part in this study.

Funding

This research was supported by the Health Technology Assessment Programme (HTA 11/69/02). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health.

Ethical approval

This study was granted approval by the relevant National Research Ethics Service Committee on 11 June 2013 (NRES Committee South Central — Berkshire) and the interview topic guide of the semi-structured interviews was approved on 4 February 2014 (REC reference: 13/SC/0206).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:71–80. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S40245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(7):712–721.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(9):1023–1034. doi: 10.1111/apt.12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What is new in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23(2):151–163. doi: 10.5056/jnm16214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care. CG61. London: NICE; 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg61 (accessed 3 Jun 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1350–1365. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everitt H, Moss-Morris R, Sibelli A, et al. Management of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care: the results of an exploratory randomised controlled trial of mebeverine, methylcellulose, placebo and a self-management website. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jakobsson Ung E, Ringstrom G, Sjovall H, Simren M. How patients with long-term experience of living with irritable bowel syndrome manage illness in daily life: a qualitative study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(12):1478–1483. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328365abd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertram S, Kurland M, Lydick E, et al. The patient’s perspective of irritable bowel syndrome. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(6):521–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakanson C. Everyday life, healthcare, and self-care management among people with irritable bowel syndrome: an integrative review of qualitative research. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2014;37(3):217–225. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ringstrom G, Sjovall H, Simren M, Ung EJ. The importance of a person-centered approach in diagnostic workups of patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a qualitative study. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2013;36(6):443–451. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farndale R, Roberts L. Long-term impact of irritable bowel syndrome: a qualitative study. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2011;12(1):52–67. doi: 10.1017/S1463423610000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casiday RE, Hungin APS, Cornford CS, et al. Patients’ explanatory models for irritable bowel syndrome: symptoms and treatment more important than explaining aetiology. Fam Pract. 2009;26(1):40–47. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olden KW. Approach to the patient with severe, refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2003;6(4):311–317. doi: 10.1007/s11938-003-0023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radziwon CD, Lackner JM. Cognitive behavioral therapy for IBS: how useful, how often, and how does it work? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(10):49. doi: 10.1007/s11894-017-0590-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everitt H, Landau S, Little P, et al. Assessing Cognitive behavioural Therapy in Irritable Bowel (ACTIB): protocol for a randomised controlled trial of clinical-effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of therapist delivered cognitive behavioural therapy and web-based self-management in irritable bowel syndrome in adults. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7):e008622. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dey I. Qualitative data analysis: a user friendly guide for social scientists. London: Routledge; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyatzis R. Transforming qualitative information. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joffe H, Yardley L. Content and thematic analysis. In: Marks D, Yardley L, editors. Research methods for clinical and health psychology. London: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sibelli A, Chalder T, Everitt H, et al. The role of high expectations of self and social desirability in emotional processing in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome: A qualitative study. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22(4):737–762. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harvey JM, Sibelli A, Chalder T, et al. Desperately seeking a cure: treatment seeking and appraisal in irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Health Psychol. 2017 doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12304. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryant A, Charmaz K. The Sage book of grounded theory. London: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creswell JW. Research design Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaeger ME, Rosnow RL. Contextualism and its implications for psychological inquiry. Br J Psychol. 1988;79(1):63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madill A, Jordan A, Shirley C. Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. Br J Psychol. 2000;91(1):1–20. doi: 10.1348/000712600161646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(2):395–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halpert A, Godena E. Irritable bowel syndrome patients’ perspectives on their relationships with healthcare providers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(7–8):823–830. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.574729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhaliwal SK, Hunt RH. Doctor–patient interaction for irritable bowel syndrome in primary care: a systematic perspective. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16(11):1161–1166. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200411000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harkness EF, Harrington V, Hinder S, et al. GP perspectives of irritable bowel syndrome — an accepted illness, but management deviates from guidelines: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casiday RE, Hungin AP, Cornford CS, et al. GPs’ explanatory models for irritable bowel syndrome: a mismatch with patient models? Fam Pract. 2009;26(1):34–39. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raine R, Carter S, Sensky T, Black N. General practitioners’ perceptions of chronic fatigue syndrome and beliefs about its management, compared with irritable bowel syndrome: qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328(7452):1354–1357. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38078.503819.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drossman DA, Chang L, Schneck S, et al. A focus group assessment of patient perspectives on irritable bowel syndrome and illness severity. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(7):1532–1541. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0792-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mik-Meyer N, Obling AR. The negotiation of the sick role: general practitioners’ classification of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Sociol Health Illn. 2012;34(7):1025–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabo B, Joffres MR, Williams T. How to deal with medically unknown symptoms. West J Med. 2000;172(2):128–130. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.2.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Houwen J, Lucassen PL, Stappers HW, et al. Improving GP communication in consultations on medically unexplained symptoms: a qualitative interview study with patients in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2017. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Dima A, Lewith GT, Little P, et al. Identifying patients’ beliefs about treatments for chronic low back pain in primary care: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Heijmans M, Hartman TCO, van Weel-Baumgarten E, et al. Experts’ opinions on the management of medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. A qualitative analysis of narrative reviews and scientific editorials. Fam Pract. 2011;28(4):444–455. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss-Morris R, McAlpine L, Didsbury LP, Spence MJ. A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural therapy-based self-management intervention for irritable bowel syndrome in primary care. Psychol Med. 2010;40(1):85–94. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pincus T, Holt N, Vogel S, et al. Cognitive and affective reassurance and patient outcomes in primary care: a systematic review. Pain. 2013;154(11):2407–2416. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson A, Lee V, Kennedy A, et al. A randomised controlled trial of self-help interventions in patients with a primary care diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55(5):643–648. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.062901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owens DM, Nelson DK, Talley NJ. The irritable-bowel-syndrome — long-term prognosis and the physician–patient interaction. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122(2):107–112. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-2-199501150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]