Abstract

Purpose

This study investigates the heritability of language, speech, and nonverbal cognitive development of twins at 4 and 6 years of age. Possible confounding effects of twinning and zygosity, evident at 2 years, were investigated among other possible predictors of outcomes.

Method

The population-based twin sample included 627 twin pairs and 1 twin without a co-twin (197 monozygotic and 431 dizygotic), 610 boys and 645 girls, 1,255 children in total. Nine phenotypes from the same comprehensive direct behavioral assessment protocol were investigated at 4 and 6 years of age. Twinning effects were estimated for each phenotype at each age using general linear mixed models using maximum likelihood.

Results

Twinning effects decreased from 4 to 6 years; zygosity effects disappeared by 6 years. Heritability increased from 4 to 6 years across all 9 phenotypes, and the heritability estimates were higher than reported previously, in the range of .44–.92 at 6 years. The highest estimate, .92, was for the clinical grammar marker.

Conclusions

Across multiple dimensions of speech, language, and nonverbal cognition, heritability estimates are robust. A finiteness marker of grammar shows the highest inherited influences in this early period of children's language acquisition.

Studies of children who are twins have accumulated consistent evidence of statistically significant genetic influence on children's language acquisition. The estimated strength of heritability varies by children's age (Hayiou-Thomas, Dale, & Plomin, 2012), the language phenotypes assessed (Rice, Zubrick, Taylor, Gayán, & Bontempo, 2014), and the language aptitude relative to age-level expectations (Hayiou-Thomas, Dale, & Plomin, 2014). In general, heritability estimates increase with age, are higher for grammar phenotypes compared to vocabulary phenotypes, and are higher for children at the lower levels of performance.

These patterns begin with 2-year-old twins, whose early vocabulary can be assessed by means of caregiver report on questionnaires. Heritability for early vocabulary acquisition in a full sample of twins is consistently estimated as approximately .25 across studies (Dale, Dionne, Eley, & Plomin, 2000; Dale et al., 1998; Rice et al., 2014), compared to .39 for sentence complexity scores (Dale et al., 2000), and .52 (for boys) and .43 (for girls) for an early finiteness-marking phenotype (Rice et al., 2014). For children selected for late language emergence, the heritability estimates for group deficits were .42 for vocabulary and .44 for the early finiteness phenotype (Rice et al., 2014).

At this early age, language acquisition is somewhat delayed for children who are twins compared to single-born children, an apparent “twinning effect,” which appears to be more likely for monozygotic (MZ) twins than dizygotic (DZ) twins (Rice et al., 2014). In order to identify a twinning delay for language acquisition, standardized, norm-referenced language assessments are required. Perhaps because these assessments require more time investment than twin data collection protocols for young children typically allow and longitudinal follow-up is necessary, there have been no reports on whether children who are twins “outgrow” an early twinning effect on language acquisition and, if so, at what ages this is evident. Note that an important implication for the early twinning effect is that it must be considered when identifying clinical populations of children with language impairment; standardized norms are established on single-born children, and twins who will “outgrow” their early language delays may have low levels of performance early on for reasons different from single-born children with low levels of language. This study examines possible twinning effects on language via direct assessments with age-standardized norms, as a first step toward subsequent study of children in the sample with language impairments, and evaluates possible persistence of zygosity effects.

Much of the recent literature on twin language development comes from the Twins Early Development Study (TEDS), a longitudinal study of twins born in England and Wales in 1994, 1995, and 1996 (Oliver & Plomin, 2007), which provides longitudinal estimates of language heritability over a large age span (2–12 years) based on data derived from parental questionnaires, telephone interviews, and web-based assessments. A study of 3,562 twin pairs (Hayiou-Thomas et al., 2012) used a latent factor variable derived from various language measures of vocabulary, syntax, and pragmatics. A heritability of .24 was obtained for early childhood (ages 2, 3, and 4), followed by an increase in middle childhood (7, 9, and 10 years) and early adolescence (12 years) to heritability estimates ranging from .47 to .59. They report a moderate genetic correlation of .38 between early and adolescent language skills, that is, the extent to which the same genetic factors affect variability in language at both ages, and a bivariate heritability of .32 (i.e., the proportion of the overall association between early and 12-year language attributable to genetic factors operating at both ages).

Also included in the larger TEDS study were investigations of a subsample of 4.5-year-old twins constructed to overrepresent children whose language and/or cognitive performance was low within the sample, based on parental report of vocabulary and grammar at age 4 and parental expressions of concern about speech and language development. There was a control group composed of randomly selected twin pairs who did not meet the criteria for low performance. Multiple measures of language and speech, as well as nonword repetition abilities, were obtained in direct assessments. In the first report (Kovas et al., 2005), univariate outcomes from the full sample of children (N = 1,574) were compared to an extremes analysis of children using −1 SD as the criterion for the low level of performance (the number of participants varied per measure, with most variables having Ns of 500–600). The results show moderate genetic influence for all aspects of language in the normal range and a similar pattern for children in the low group, with no sex differences. A follow-up multivariate genetic analysis for the full 4.5-year sample (Hayiou-Thomas et al., 2006) reported two latent factor phenotypes, articulation and general language. The genetic influence was estimated as 0.34 for the general language factor and 0.64 for articulation, with the genetic correlation between the two latent factors at .64, suggesting largely but not entirely overlapping genetic influence. A subsequent paper (Hayiou-Thomas, 2008) concludes there is a significant etiological distinction between speech and language, such that the dominant influences on language stem from children's shared environment whereas the dominant influences on speech are genetic.

Although the TEDS study has provided very important new insights about genetic influences on language acquisition and the etiology of language impairments in children, there are acknowledged limitations to the outcomes (Hayiou-Thomas et al., 2014). One gap is the lack of follow-up for twins assessed at 4.5 years to determine if heritability estimates are stable during the early childhood period, when speech and language are undergoing dynamic change. Another gap in the literature is a lack of detailed age-referenced descriptions for speech and language phenotypes during this period across the domains of speech, omnibus language assessments, vocabulary, and grammar. Sometimes nonstandardized measures have been used; even when standardized measures were used, a comparison with age norms was not a focus of study.

These gaps are partially filled by outcomes of two previous twin studies. A sample of 487 twins at first grade and 387 twins at second grade investigated language heritability from conversational speech sample phenotypes (DeThrone, Harlaar, Petrill, & Deater-Deckard, 2012). Of interest here is the estimate for mean length of utterance (MLU) at both times of measurement. At both times of measurement, heritability estimates were significant, .50 in first grade and .28 at second grade in ACE models. Another study (Olson et al., 2011) investigated vocabulary development as related to reading development in a sample of 997 twin pairs at preschool, Grade 2, and Grade 4. Of interest here are the vocabulary outcomes, estimated from different vocabulary tests at different age levels. The results were more environmental than heritable influences in preschool, followed by an increase in genetic influences in the two subsequent times when shared environment and heritable influence were more comparable.

In this study, we address these assessment gaps in a prospective population-based ascertainment of twin children. This study reports on language and speech outcomes at 4 and 6 years, an important growth period for language acquisition, which establishes speech and language competencies that serve as the basis for subsequent academic success. The phenotypes are comprehensive, focusing on vocabulary, morphosyntax, and general language measures, as well as speech measures. The phenotypes also are adjusted for age expectations compared to normative test scores. The study uniquely addresses whether the twinning effect at 2 years persists to 4 and 6 years. The predictive models included evaluation of potential perinatal risk indicators. Twin boys are more likely than girls to show late language emergence (Rice et al., 2014); birth weight and 1- and 5-min APGAR scores tend to be lower in twins than in single-born children (Liu & Blair, 2002), and maternal age is a predictor of birth weight in both twins and singletons (Blair, Liu, de Klerk, & Lawrence, 2005; Liu & Blair, 2002). Maternal education is a proxy index for resources in the home thought to nurture children's cognitive development (Entwisle & Astone, 1994), although it is also known to have high heritability.

The study addressed the following questions:

Are twinning effects (i.e., lower than expected standard score means) present across the nine phenotypes for language, speech, and nonverbal IQ at 4 and 6 years of age?

Are zygosity effects (i.e., lower performance by MZ twins) evident at 4 and 6 years of age?

Are effects of twin pair–level predictors (maternal education, maternal age) and individual twin–level predictors (sex, within-occasion age deviation, birth weight, 1- and 5-min APGAR scores) present across these nine phenotypes at 4 and 6 years of age?

Do these nine phenotypes show evidence of heritability at 4 and 6 years of age?

Method

Participants

The study design was a prospective cohort study of twins, primarily drawn from a total population sample frame comprising statutory notifications of all births in Western Australia in 2000–2003 (Gee & Green, 2004). The population of Western Australia is demographically similar to some states in the Midwestern United States. For example, census data show that the population of the state of Kansas is 2.7 million, and the population of Western Australia is 2.1 million. In each state, most of the population is in urban areas. The states are predominantly Caucasian (86% for Kansas, 96% for Western Australia), and the majority of the population are native speakers of English, well-educated (86% of the population has completed high school in each state), and family-oriented (in Kansas, 55% of all families are couple families with children, and 9% are sole-parent families; in Western Australia, these rates are 49% and 15%, respectively). On a wide variety of behavioral and biological assessments of children and adults, distributional outcomes conform to normative expectations for instruments normed in the United States or the United Kingdom.

There were 1,135 sets of live twins born in this time period. We were able to trace 941 (83%) of these twin families by mail, and 703 (75%) consented to participate in the study. This represents ascertainment of 62% of all twins born in Western Australia in 2000–2003. A comparison with data available for all twins born 2000–2003 showed that the participants were broadly representative of the total twin population from which it was drawn. The majority of mothers in the participant group were Caucasian, 20–34 years of age, married, and living in the metropolitan area. The participant group, compared to the nonparticipant group, contained more Caucasian mothers, married mothers, and fewer young mothers. This is consistent with other population-level studies using the same recruitment methods, drawn from the same region with similar socioeconomic status (SES) distributions (Zubrick, Taylor, Rice, & Slegers, 2007). There was no significant difference in the percentage of participants versus nonparticipants living in the metropolitan or rural regions of Western Australia.

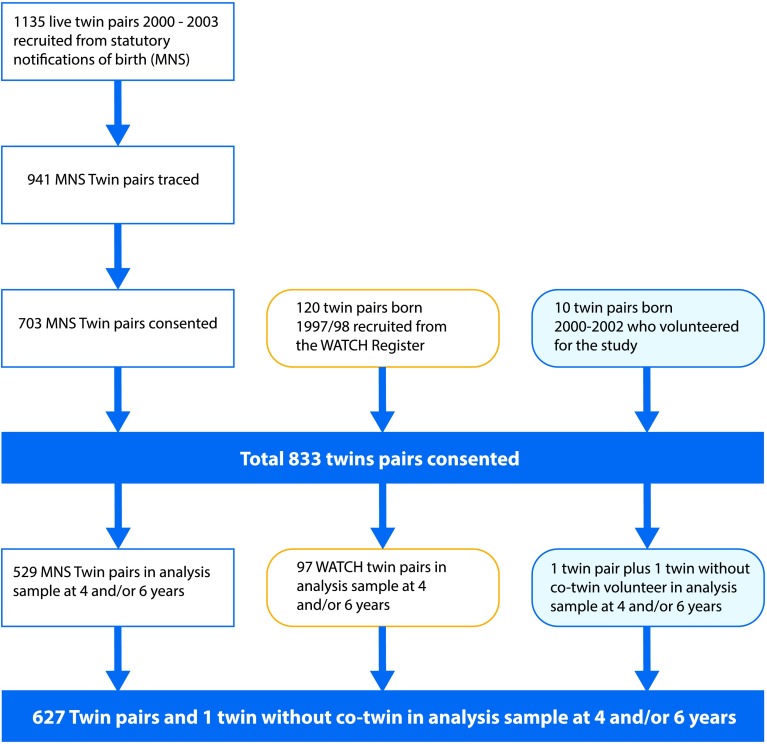

The study also included 120 twin pairs from the Western Australian Twin Child Health study, born 1997–1998 (Hansen, Alessandri, Croft, Burton, & de Klerk, 2004). Ten additional families with twins born 2000–2002, who were not recruited through the statutory notification of births, approached the study and were included in the cohort. The overall recruitment is reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Recruitment of twin sample. MNS = Midwives’ Notification System; WATCH = Western Australian Twin Child Health study.

Exclusionary criteria were applied to form the final sample. Twins with exposure to languages other than English (52 twin pairs) or twin pairs in which at least one twin had hearing impairment, neurological disorders, or developmental disorders (14 twin pairs) were later excluded from the twin sample. Exclusionary conditions included Down syndrome, Angelman syndrome, cerebral palsy, cleft lip and/or palate, agenesis of the corpus callosum, and global developmental delay. The intent was to limit the sample to children who did not have concurrent conditions likely to affect language acquisition.

The analysis sample comprised children who provided data at age 4 and/or age 6 on the outcome measures. After restricting the sample to those who had all measured outcomes and covariates (as listed below), the analysis sample comprised 1,255 children from 627 pairs and one twin without a co-twin. The twin pairs included 103 MZ girls, 93 MZ boys, 108 DZ girls, 100 DZ boys, and 223 DZ opposite sex pairs. A total of 523 pairs and one singleton had outcomes for both ages, whereas 41 and 63 pairs only had outcomes at age 4 or age 6, respectively.

At 4 years, 18 participants (1.61%) failed the hearing screening; at 6 years, 26 failed (2.08%). One child (an MZ twin) wore a hearing aid; another child was reported to be deaf in one ear (DZ twin). Both children performed in low range for most of the phenotype measurements. Other children who failed hearing screenings performed in the normal range or above in almost all the assessments and had no parental report of clinically significant hearing loss. In the sample, nonverbal IQ was normally distributed at 4 and 6 years, with a mean of 104.64 (SD = 11.81) at 4 years and a mean of 102.88 (SD = 12.63) at 6 years.

The initial sample and the analytic sample can be compared on three postal area measures of SES calculated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2001) from national census data. The measures were the Index of Socio-Economic Disadvantage, the Index of Economic Resources, and the Index of Education and Occupation. For all children where consent was given and the socioeconomic measures were available, the mean for Disadvantage was 1,008.6, the mean for Resources was 1,013.8, and the mean for Education/Occupation was 998.2. For all children in the analytic sample with available socioeconomic measures, the mean for Disadvantage was 1,009.1, the mean for Resources was 1,014.6, and the mean for Education/Occupation was 998.0. The consented and analytic samples are very similar on these measures.

Measures and Procedure

At 4 and 6 years, we followed the same protocols for speech, language, and nonverbal intelligence assessments. The protocol was designed to provide comprehensive assessment of language and speech development and to include an assessment of nonverbal intelligence for the purpose of characterizing the cognitive abilities of the sample as well as heritability estimates. Pure-tone hearing screenings (500, 1,000, 2,000, and 4,000 Hz) were conducted at each time of measurement with headphones in everyday ambient noise in field testing; a pass was defined as a participant responding to each frequency in either the right or left ear at 25 or 30 dB. Vocabulary was assessed with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition (PPVT-3; Dunn & Dunn, 1997). An omnibus assessment of language was obtained with the Test of Oral Language Development–Primary: Third Edition (TOLD-P:3; Newcomer & Hammill, 1997), which provided two subset scores for semantics and syntax. Nonverbal intelligence was assessed with the Columbia Mental Maturity Scale (CMMS; Burgemeister, Blum, & Lorge, 1972). The Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Second Edition (GFTA-2; Goldman & Fristoe, 2000) provided percentile scores for speech development. It was not necessary to adapt the assessments for Australian English; the population norms apply as in the United States, as reported in a study of 144 single-born children aged 7 years (Rice, Taylor, & Zubrick, 2008). We collected spontaneous language samples (mean number of utterances = 202.9, SD = 68.7 for 4-year samples; mean number of utterances = 215.1, SD = 84.8 for 6-year samples) and calculated MLU (Miller & Chapman, 2002; Rice, Redmond, & Hoffman, 2006; Rice et al., 2010). We evaluated the grammatical property of finiteness marking, a clinical marker of language impairment, using the Rice–Wexler Test of Early Grammatical Impairment (TEGI; Rice & Wexler, 2001). The TEGI yielded two scores of morphosyntax: Elicited Grammar Composite (tasks evaluating production of third-person singular -s, past tense, BE auxiliary and copula, and DO auxiliary in obligatory sentence contexts) and a Screening Test Score (third-person singular -s and past tense production in sentences). All outcome scores were age-adjusted standard scores. For TEGI, the standard scores were calculated from means and standard deviations provided in the manual. For GFTA-2, percentile scores were used. There were a total of nine phenotypes: vocabulary, three from omnibus language assessment (spoken language, semantics, and syntax), nonverbal IQ, speech, MLU, and two morphosyntactic measures from TEGI (finiteness grammar composite and third-person singular -s and past tense obligatory use).

Analytic Strategy

The research questions were addressed for each of the nine phenotypes obtained at 4 and 6 years of age using general linear mixed models as estimated using maximum likelihood. The significance of fixed effects was evaluated via their Wald test p values, and nested model comparisons were conducted via likelihood ratio tests (i.e., by comparing the −2 times the difference in model log-likelihood to a χ2 distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of estimated parameters). Phenotype outcomes for individual twins as Level 1 were nested within twin pairs as Level 2, and their responses at ages 4 and 6 years were predicted simultaneously as correlated multivariate outcomes within separate models for each phenotype. All variances and covariances were estimated as heterogeneous by age and zygosity given significant improvements in model fit upon doing so for most phenotypes (i.e., all but MLU for age). This mixed modeling strategy thus permits inclusion of all individual twins in all analyses given that their dependency within pairs can be properly accounted for by random effects variances and covariances (Guo & Wang, 2002). Likewise, it does not restrict the sample to those twins with outcomes at both ages 4 and 6 years. Furthermore, because inspection of the Level 1 residuals suggested plausible normality, no data transformations were needed (Hoffman, 2015; Snijders & Bosker, 2012).

As reported below, empty means (i.e., intercept only) models were first estimated to examine the extent of twinning effects (RQ1) and zygosity effects (RQ2), followed by conditional models to examine the pair-level and twin-level predictor effects (RQ3); all of these models were estimated using SAS MIXED (SAS Institute, 2017). Effect sizes for the conditional models were expressed as total R 2, which is the squared correlation between the fixed-effect predicted and obtained outcome values (Hoffman, 2015). Finally, the exact same conditional models were reestimated using structural equation software (Mplus v 7.4; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015) in order to obtain estimates, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals for the conditional models' repeated-measures correlations, intraclass correlations (ICCs), and heritability estimates (RQ4), as reported below.

Results

Unconditional Models: Twinning Effects

With respect to twinning and zygosity effects (RQ1–2), Table 1 provides the phenotype means, their standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals by age and zygosity for the nine phenotypes. As shown in the third to last column, 20 of the 36 sample means were significantly lower than expected based on population means; only three were higher than expected. This can be viewed as a persistent twinning effect across various language and speech phenotypes, ages 4 and 6, and zygosity. The last two columns of Table 1 indicate two types of significant differences at the α < .01 level: for age differences within zygosity and for zygosity differences within age. Children had higher standard scores at age 6 than at age 4 for all phenotypes, except GFTA-2 Speech, for which age 4 was higher than age 6 instead (which may be attributable to the unique psychometric properties of measuring speech development in this age range). Furthermore, although MZ twins had significantly lower scores than DZ twins at age 4 for six phenotypes (PPVT-3, TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language, TOLD-P:3 Semantics, TOLD-P:3 Syntax, TEGI Composite, and TEGI Screener), there were no significant zygosity differences at age 6 for any phenotype.

Table 1.

Standard score means, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) by phenotype, age, and zygosity.

| Phenotype | Age | Zygosity | n | Mean | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | CI excludes population mean | Age difference | Zygosity difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPVT-3 Vocabulary | 4 | DZ | 771 | 96.78 | 0.59 | 95.62 | 97.93 | − | * | |

| MZ | 357 | 93.91 | 0.91 | 92.11 | 95.70 | − | ||||

| 6 | DZ | 798 | 101.93 | 0.45 | 101.06 | 102.81 | + | * | ||

| MZ | 372 | 100.28 | 0.79 | 98.73 | 101.83 | * | ||||

| TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language | 4 | DZ | 761 | 90.52 | 0.50 | 89.53 | 91.50 | − | * | |

| MZ | 346 | 87.46 | 0.70 | 86.09 | 88.83 | − | ||||

| 6 | DZ | 800 | 93.10 | 0.56 | 92.01 | 94.20 | − | * | ||

| MZ | 373 | 91.03 | 0.93 | 89.19 | 92.87 | − | * | |||

| TOLD-P:3 Semantics | 4 | DZ | 762 | 91.03 | 0.49 | 90.07 | 92.00 | − | * | |

| MZ | 346 | 88.42 | 0.65 | 87.13 | 89.71 | − | ||||

| 6 | DZ | 800 | 93.79 | 0.54 | 92.73 | 94.86 | − | * | ||

| MZ | 373 | 91.81 | 0.87 | 90.08 | 93.53 | − | * | |||

| TOLD-P:3 Syntax | 4 | DZ | 761 | 91.29 | 0.53 | 90.26 | 92.32 | − | * | |

| MZ | 346 | 88.29 | 0.80 | 86.72 | 89.86 | − | ||||

| 6 | DZ | 800 | 93.44 | 0.58 | 92.30 | 94.59 | − | * | ||

| MZ | 373 | 91.50 | 1.01 | 89.52 | 93.49 | − | * | |||

| CMMS Nonverbal IQ | 4 | DZ | 767 | 101.78 | 0.56 | 100.68 | 102.89 | |||

| MZ | 353 | 99.85 | 0.82 | 98.23 | 101.48 | |||||

| 6 | DZ | 799 | 104.98 | 0.47 | 104.06 | 105.91 | + | * | ||

| MZ | 373 | 104.32 | 0.76 | 102.81 | 105.83 | + | * | |||

| GFTA-2 Speech | 4 | DZ | 766 | 55.67 | 0.97 | 53.77 | 57.57 | |||

| MZ | 348 | 51.85 | 1.72 | 48.45 | 55.25 | |||||

| 6 | DZ | 797 | 42.17 | 0.76 | 40.68 | 43.66 | * | |||

| MZ | 369 | 39.00 | 1.30 | 36.43 | 41.57 | * | ||||

| Mean length of utterance | 4 | DZ | 753 | 97.79 | 0.72 | 96.37 | 99.20 | − | ||

| MZ | 336 | 95.73 | 1.27 | 93.23 | 98.24 | − | ||||

| 6 | DZ | 797 | 101.30 | 0.69 | 99.96 | 102.65 | * | |||

| MZ | 369 | 100.27 | 1.08 | 98.14 | 102.40 | * | ||||

| TEGI Composite | 4 | DZ | 753 | 86.97 | 0.90 | 85.20 | 88.74 | * | ||

| MZ | 332 | 81.51 | 1.67 | 78.22 | 84.80 | |||||

| 6 | DZ | 796 | 93.12 | 0.89 | 91.36 | 94.88 | * | |||

| MZ | 371 | 88.91 | 1.75 | 85.47 | 92.36 | * | ||||

| TEGI Screener | 4 | DZ | 757 | 88.71 | 0.89 | 86.96 | 90.45 | − | * | |

| MZ | 339 | 83.94 | 1.57 | 80.83 | 87.05 | − | ||||

| 6 | DZ | 797 | 97.17 | 0.79 | 95.62 | 98.71 | − | * | ||

| MZ | 371 | 93.44 | 1.58 | 90.33 | 96.55 | − | * |

Note. + = higher sample mean, − = lower sample mean. PPVT-3 = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition; TOLD-P:3 = Test of Oral Language Development–Primary: Third Edition; CMMS = Columbia Mental Maturity Scale; GFTA-2 = Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Second Edition; TEGI = Rice–Wexler Test of Early Grammatical Impairment; DZ = dizygotic; MZ = monozygotic.

p < .01.

Conditional Models: Effects of Predictors

Strategy

Conditional models were then specified to examine predictor effects (RQ3) in accordance with their multilevel variation. That is, because maternal education and maternal age are pair-level predictors, they can only explain between-pairs (Level 2) random intercept variation. In contrast, the other twin-specific predictors—actual age at each assessment, sex, birth weight, and 1- and 5-min APGAR scores—can explain within-pair (Level 1) residual variation. However, to the extent that the twins share common variance in these predictors, they can also show a between-pairs effect as well. The extent of common variance in each predictor can be indexed by the twins' ICC, which is the proportion of total variance attributable to pair-level random intercept variation (i.e., that is due to mean differences between twin pairs). Indeed, ICCs estimated separately by zygosity and age (as needed, given that not all the same children were included at ages 4 and 6) ranged from .70 to .81 for birth weight, from .25 to .29 for 1-min APGAR, and from .37 to .45 for 5-min APGAR, indicating sizable and significant proportions of between-pairs variation in each (as given by the ICC) as well as within-pair variation (as found from 1 − ICC). Consequently, both the between-pairs and within-pair effects of these predictors were examined, as described next. Likewise, sex composition of the twin pairs was examined in addition to individual sex.

To account for imbalance in the timing of the measurement occasions, we also controlled for linear and quadratic effects of the offset of the actual assessment age from the target age of 4 or 6 years for each twin (offset M = 1.88 months, SD = 4.23, range = −5.90 to 23.18). This age offset variable had an ICC ~ 1.00, reflecting the fact that almost all of the co-twins were assessed within a few days of each other. For the 4-year-olds, 97.7% were seen within 7 days of each other; for the 6-year-olds, 95.6% were seen within 7 days of each other. Finally, given the large number of effects to be tested, an alpha level of .01 was used to declare significance for all fixed effects described below.

Table 2 provides the results from conditional models, including all predictors for each phenotype. Separate effects were estimated for ages 4 and 6, and significant differences in these unstandardized effects across age are indicated in the last column of Table 2. Preliminary analyses also examined moderation of each effect by zygosity, but none was found, and thus, all predictor effects were constrained to be equal across DZ and MZ twins. The intercept was allowed to differ by zygosity, however, as three of the phenotypes were significantly lower for MZ than DZ twins at age 4. Total R 2 ranged from a low of .068 (TEGI Composite) to a high of .151 (TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language).

Table 2.

Pair-level and twin-level predictor effects by phenotype and age.

| Parameter | Age 4 |

Age 6 |

Age difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | p < | Est | SE | p < | ||

| PPVT-3 Vocabulary (R 2 = .150) | |||||||

| DZ vs. MZ | −1.99 | 1.04 | .056 | −1.31 | 0.86 | .131 | |

| Maternal education | 1.41 | 0.20 | .001 | 1.17 | 0.16 | .001 | |

| Maternal age | 0.39 | 0.09 | .001 | 0.29 | 0.08 | .001 | |

| Boy vs. girl | 1.66 | 0.72 | .022 | 0.32 | 0.58 | .590 | |

| Linear age offset | 0.27 | 0.24 | .256 | −0.06 | 0.12 | .628 | |

| Quadratic age offset | 0.01 | 0.02 | .426 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .358 | |

| WP birth weight | 4.94 | 1.38 | .001 | 0.77 | 1.11 | .489 | * |

| BP birth weight | 0.81 | 0.95 | .399 | 0.86 | 0.75 | .252 | |

| WP 1-min APGAR | 0.45 | 0.32 | .170 | 0.34 | 0.26 | .191 | |

| BP 1-min APGAR | −0.40 | 0.50 | .423 | −0.19 | 0.38 | .625 | |

| WP 5-min APGAR | −0.59 | 0.67 | .377 | 0.32 | 0.53 | .544 | |

| BP 5-min APGAR | −0.16 | 0.88 | .858 | −0.69 | 0.67 | .307 | |

| TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language (R 2 = .151) | |||||||

| DZ vs. MZ | −2.33 | 0.80 | .004 | −1.74 | 1.04 | .096 | |

| Maternal education | 1.29 | 0.16 | .001 | 1.62 | 0.19 | .001 | |

| Maternal age | 0.30 | 0.08 | .001 | 0.35 | 0.09 | .001 | |

| Boy vs. girl | 2.93 | 0.56 | .001 | 2.90 | 0.67 | .001 | |

| Linear age offset | 0.65 | 0.19 | .001 | −0.46 | 0.14 | .001 | * |

| Quadratic age offset | −0.02 | 0.01 | .220 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .042 | |

| WP birth weight | 2.72 | 0.98 | .005 | 3.44 | 1.15 | .003 | |

| BP birth weight | 0.57 | 0.78 | .464 | 0.85 | 0.91 | .349 | |

| WP 1-min APGAR | 0.08 | 0.22 | .727 | 0.36 | 0.26 | .159 | |

| BP 1-min APGAR | −0.52 | 0.40 | .201 | −0.77 | 0.46 | .097 | |

| WP 5-min APGAR | 0.23 | 0.47 | .634 | −0.47 | 0.54 | .381 | |

| BP 5-min APGAR | 1.13 | 0.71 | .112 | 0.95 | 0.81 | .242 | |

| TOLD-P:3 Semantics (R 2 = .134) | |||||||

| DZ vs. MZ | −1.89 | 0.76 | .013 | −1.79 | 1.00 | .075 | |

| Maternal education | 1.24 | 0.16 | .001 | 1.40 | 0.19 | .001 | |

| Maternal age | 0.28 | 0.07 | .001 | 0.27 | 0.09 | .002 | |

| Boy vs. girl | 2.93 | 0.60 | .001 | 2.05 | 0.73 | .005 | |

| Linear age offset | 0.69 | 0.21 | .001 | −0.49 | 0.15 | .001 | * |

| Quadratic age offset | −0.01 | 0.02 | .334 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .229 | |

| WP birth weight | 1.61 | 1.22 | .188 | 2.46 | 1.39 | .076 | |

| BP birth weight | 0.06 | 0.75 | .933 | 0.82 | 0.89 | .359 | |

| WP 1-min APGAR | −0.06 | 0.29 | .829 | 0.58 | 0.32 | .067 | |

| BP 1-min APGAR | −0.64 | 0.39 | .105 | −0.60 | 0.45 | .189 | |

| WP 5-min APGAR | 0.41 | 0.59 | .494 | −0.07 | 0.66 | .920 | |

| BP 5-min APGAR | 1.13 | 0.69 | .105 | 0.74 | 0.79 | .348 | |

| TOLD-P:3 Syntax (R 2 = .118) | |||||||

| DZ vs. MZ | −2.38 | 0.92 | .010 | −1.52 | 1.11 | .174 | |

| Maternal education | 1.13 | 0.18 | .001 | 1.60 | 0.20 | .001 | * |

| Maternal age | 0.27 | 0.09 | .002 | 0.38 | 0.10 | .001 | |

| Boy vs. girl | 2.60 | 0.65 | .001 | 3.11 | 0.73 | .001 | |

| Linear age offset | 0.50 | 0.21 | .019 | −0.39 | 0.15 | .008 | * |

| Quadratic age offset | −0.02 | 0.02 | .290 | 0.03 | 0.01 | .037 | |

| WP birth weight | 3.72 | 1.14 | .001 | 3.91 | 1.29 | .002 | |

| BP birth weight | 1.14 | 0.86 | .186 | 0.84 | 0.97 | .390 | |

| WP 1-min APGAR | 0.32 | 0.26 | .223 | 0.12 | 0.29 | .681 | |

| BP 1-min APGAR | −0.37 | 0.45 | .413 | −0.86 | 0.50 | .084 | |

| WP 5-min APGAR | −0.06 | 0.55 | .913 | −0.80 | 0.61 | .189 | |

| BP 5-min APGAR | 0.96 | 0.79 | .225 | 1.06 | 0.87 | .220 | |

| CMMS Nonverbal IQ (R 2 = .092) | |||||||

| DZ vs. MZ | −1.14 | 0.96 | .233 | −0.31 | 0.88 | .728 | |

| Maternal education | 1.01 | 0.19 | .001 | 0.45 | 0.17 | .009 | * |

| Maternal age | 0.25 | 0.09 | .005 | 0.24 | 0.08 | .003 | |

| Boy vs. girl | 2.91 | 0.74 | .001 | 2.57 | 0.68 | .001 | |

| Linear age offset | −0.08 | 0.26 | .758 | −0.34 | 0.14 | .015 | |

| Quadratic age offset | 0.03 | 0.02 | .178 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .071 | |

| WP birth weight | 3.56 | 1.50 | .018 | −0.12 | 1.35 | .927 | |

| BP birth weight | 2.95 | 0.91 | .001 | 2.59 | 0.81 | .001 | |

| WP 1-min APGAR | 0.04 | 0.35 | .918 | 0.50 | 0.31 | .111 | |

| BP 1-min APGAR | −0.81 | 0.48 | .088 | −0.10 | 0.41 | .808 | |

| WP 5-min APGAR | 0.22 | 0.73 | .758 | −0.06 | 0.64 | .926 | |

| BP 5-min APGAR | 0.34 | 0.84 | .686 | −0.49 | 0.72 | .502 | |

| GFTA-2 Speech (R 2 = .104) | |||||||

| DZ vs. MZ | −3.78 | 1.98 | .057 | −2.72 | 1.50 | .071 | |

| Maternal education | 0.66 | 0.36 | .071 | 0.88 | 0.28 | .002 | |

| Maternal age | 0.24 | 0.17 | .164 | 0.17 | 0.14 | .207 | |

| Boy vs. girl | −0.55 | 1.44 | .702 | 0.58 | 1.16 | .616 | |

| Linear age offset | −0.21 | 0.49 | .675 | −0.18 | 0.23 | .432 | |

| Quadratic age offset | −0.02 | 0.04 | .559 | 0.01 | 0.02 | .796 | |

| WP birth weight | 2.13 | 2.76 | .441 | 1.31 | 2.30 | .570 | |

| BP birth weight | 0.78 | 1.73 | .652 | 2.47 | 1.35 | .068 | |

| WP 1-min APGAR | −0.89 | 0.64 | .165 | −0.26 | 0.53 | .624 | |

| BP 1-min APGAR | −0.17 | 0.91 | .847 | 0.19 | 0.69 | .782 | |

| WP 5-min APGAR | 1.54 | 1.33 | .247 | 1.29 | 1.09 | .238 | |

| BP 5-min APGAR | 1.00 | 1.59 | .531 | −0.55 | 1.20 | .646 | |

| Mean Length of Utterance (R 2 = .082) | |||||||

| DZ vs. MZ | −0.95 | 1.42 | .506 | −1.44 | 1.25 | .250 | |

| Maternal education | 1.49 | 0.25 | .001 | 0.94 | 0.24 | .001 | |

| Maternal age | 0.26 | 0.12 | .032 | 0.09 | 0.12 | .437 | |

| Boy vs. girl | 1.43 | 1.06 | .177 | 2.20 | 1.04 | .035 | |

| Linear age offset | −1.20 | 0.38 | .002 | −0.96 | 0.22 | .001 | |

| Quadratic age offset | 0.12 | 0.03 | .001 | 0.05 | 0.02 | .006 | |

| WP birth weight | 1.53 | 2.11 | .469 | 2.09 | 2.19 | .341 | |

| BP birth weight | 0.43 | 1.21 | .722 | 0.58 | 1.18 | .624 | |

| WP 1-min APGAR | 0.55 | 0.49 | .261 | 1.13 | 0.51 | .026 | |

| BP 1-min APGAR | −1.45 | 0.64 | .023 | −1.84 | 0.59 | .002 | |

| WP 5-min APGAR | −2.96 | 1.01 | .004 | 0.81 | 1.04 | .437 | * |

| BP 5-min APGAR | 2.41 | 1.12 | .031 | 0.46 | 1.04 | .658 | |

| TEGI Composite (R 2 = .068) | |||||||

| DZ vs. MZ | −5.19 | 1.88 | .006 | −2.97 | 1.91 | .121 | |

| Maternal education | 1.62 | 0.33 | .001 | 1.50 | 0.34 | .001 | |

| Maternal age | 0.41 | 0.16 | .011 | 0.44 | 0.16 | .006 | |

| Boy vs. girl | 1.44 | 1.16 | .216 | −0.61 | 1.29 | .638 | |

| Linear age offset | 0.37 | 0.41 | .359 | 0.45 | 0.25 | .073 | |

| Quadratic age offset | −0.04 | 0.03 | .195 | 0.02 | 0.02 | .438 | |

| WP birth weight | −1.20 | 2.04 | .555 | −2.04 | 2.28 | .372 | |

| BP birth weight | −0.82 | 1.59 | .606 | 1.65 | 1.61 | .303 | |

| WP 1-min APGAR | 0.45 | 0.47 | .338 | 0.04 | 0.51 | .930 | |

| BP 1-min APGAR | −0.92 | 0.83 | .268 | −1.20 | 0.82 | .145 | |

| WP 5-min APGAR | −0.02 | 0.97 | .985 | 0.37 | 1.07 | .734 | |

| BP 5-min APGAR | 1.72 | 1.46 | .238 | 1.66 | 1.43 | .247 | |

| TEGI Screener (R 2 = .085) | |||||||

| DZ vs. MZ | −4.12 | 1.79 | .022 | −2.69 | 1.72 | .120 | |

| Maternal education | 1.46 | 0.32 | .001 | 0.96 | 0.30 | .001 | |

| Maternal age | 0.49 | 0.15 | .001 | 0.34 | 0.14 | .017 | |

| Boy vs. girl | 1.92 | 1.15 | .096 | 0.31 | 1.16 | .790 | |

| Linear age offset | 0.05 | 0.42 | .911 | 0.48 | 0.23 | .040 | |

| Quadratic age offset | 0.00 | 0.03 | .869 | 0.02 | 0.02 | .306 | |

| WP birth weight | 2.19 | 1.96 | .266 | −0.76 | 2.26 | .738 | |

| BP birth weight | 0.09 | 1.54 | .955 | 1.51 | 1.42 | .289 | |

| WP 1-min APGAR | 0.97 | 0.45 | .032 | −0.23 | 0.53 | .668 | |

| BP 1-min APGAR | −1.48 | 0.80 | .066 | −0.60 | 0.73 | .406 | |

| WP 5-min APGAR | −1.22 | 0.95 | .198 | 1.43 | 1.08 | .183 | |

| BP 5-min APGAR | 2.31 | 1.42 | .104 | 0.73 | 1.27 | .564 | |

Note. Significant effects are in bold. Est = estimate; WP = within-pair; BP = between-pairs; PPVT-3 = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition; TOLD-P:3 = Test of Oral Language Development–Primary: Third Edition; CMMS = Columbia Mental Maturity Scale; GFTA-2 = Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Second Edition; TEGI = Rice–Wexler Test of Early Grammatical Impairment; DZ = dizygotic; MZ = monozygotic.

p < .01.

Maternal Education and Maternal Age

Both maternal predictors were included as between-pairs (Level 2) predictors, in which maternal education was centered at a value of 8 and maternal age was centered at 30 years. There was a consistent positive effect of maternal education across predictors: All nine phenotypes were significantly higher for twins from more educated mothers at age 6, and all but one phenotype was at age 4 as well (GFTA-2 Speech was the exception). Two phenotypes showed differential effects of maternal education across twin age (TOLD-P:3 Syntax and CMMS Nonverbal IQ). With respect to maternal age, there was a significant positive effect at both ages for five phenotypes (PPVT-3 Vocabulary, TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language, TOLD-P:3 Semantics, TOLD-P:3 Syntax, and CMMS Nonverbal IQ), as well as at age 6 only for TEGI Composite and age 4 only for TEGI Screener (GTFA Speech and MLU did not have significant effects of maternal age). There were no significant differences in the effect of maternal age between ages 4 and 6 years. Quadratic maternal age effects were examined but were not significant, and so only linear effects were included.

Sex and Age Offset

Girls significantly outperformed boys (as the reference group) for four phenotypes equivalently at both ages 4 and 6 years (TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language, TOLD-P:3 Semantics, TOLD-P:3 Syntax, and CMMS Nonverbal IQ), but there were no further effects of sex composition of the twin pair. Age offset (i.e., the difference in assessment age from the target age of 4 or 6 in months) had inconsistent effects across phenotypes; TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language and TOLD-P:3 Semantics had significant positive linear effects at age 4 but significant negative effects at age 6. In addition, one phenotype showed decelerating negative curves for the effect of age offset: MLU had a negative linear effect at ages 4 and 6 years paired with a positive quadratic effect.

Birth Weight and APGAR Scores

For each variable, the pair mean was included as a between-pairs (Level 2) predictor, and the within-pair deviation from the pair mean was included as the within-pair (Level 1) predictor. With respect to birth weight in kilograms, pair mean weight (centered at two) had a significant positive effect on CMMS Nonverbal IQ equivalently at ages 4 and 6 years, such that heavier-born twin pairs had greater nonverbal IQ, but no other between-pairs effects of birth weight were significant. Two phenotypes had significant positive within-pair effects of birth weight at both ages (TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language and TOLD-P:3 Syntax), as well as PPVT-3 Vocabulary at age 4, such that being heavier at birth than one's twin predicted a relatively greater phenotype than one's twin at that age. The within-pair effect of birth weight was significantly greater at age 4 than at age 6 for only one phenotype (PPVT-3 Vocabulary). With respect to 1-min and 5-min APGAR scores, their pair means were each centered at eight, but only one significant between-pairs effect was found—a negative effect for pair mean 1-min APGAR for MLU at age 6, such that pairs with greater APGAR scores 1 min after birth were predicted to have lower mean MLU phenotypes. Finally, MLU had a significant negative within-pair effect of 5-min APGAR at age 4, but no other within-pair APGAR effects were significant.

Conditional Models: Repeated Measures Correlations

The phenotype variance and covariance unaccounted for by the conditional model was then examined for correspondence across age at each level of analysis, as well as across twins. First, Table 3 provides the estimates, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals for three types of repeated measures correlations across age for each phenotype by zygosity. As shown in the first set of columns, the within-person correlations indicate the similarity across age of a child's ranking relative to his or her peers. This is a measure of the extent to which a child who scored higher than other children at age 4 also did so at age 6. That is, the within-person correlation measures the extent to which children with better language and speech maintain their advantage over age peers over time or, conversely, the extent to which children with lower levels of language and speech language development maintain a lower position relative to age peers (even though they may be learning new language and speech skills). The within-person correlations ranged across phenotypes from lows of .25 for DZ twins and .29 for MZ twins (both for MLU) to highs of .65 for DZ twins (for TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language) and .67 for MZ twins (for TEGI Composite; TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language was .66). Out of the 18 within-person correlations, 16 were .44 or above, 12 of which were .5 and higher, suggesting moderately high consistency (Cohen, 1988) of language and speech rank between 4 and 6 years across multiple phenotypes.

Table 3.

Conditional model repeated-measures correlations by phenotype and zygosity.

| Phenotype | Zygosity | Within-person correlations |

Between-pairs correlations |

Within-pair correlations |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | LCI | UCI | Est | SE | LCI | UCI | Est | SE | LCI | UCI | ||

| PPVT-3 Vocabulary | DZ | .61 | .03 | .56 | .66 | .87 | .05 | .78 | .96 | .41 | .04 | .33 | .49 |

| MZ | .61 | .04 | .53 | .68 | .95 | .05 | .86 | 1.04 | .04 | .07 | −.11 | .18 | |

| TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language | DZ | .65 | .02 | .60 | .69 | .88 | .04 | .81 | .96 | .41 | .04 | .33 | .49 |

| MZ | .66 | .04 | .58 | .73 | .82 | .04 | .74 | .90 | .09 | .07 | −.06 | .23 | |

| TOLD-P:3 Semantics | DZ | .45 | .03 | .39 | .52 | .90 | .08 | .75 | 1.04 | .20 | .05 | .11 | .30 |

| MZ | .44 | .05 | .34 | .54 | .72 | .08 | .56 | .88 | .08 | .07 | −.06 | .23 | |

| TOLD-P:3 Syntax | DZ | .62 | .02 | .57 | .66 | .86 | .04 | .77 | .94 | .41 | .04 | .33 | .49 |

| MZ | .66 | .04 | .59 | .73 | .82 | .04 | .75 | .90 | .14 | .07 | .00 | .28 | |

| CMMS Nonverbal IQ | DZ | .45 | .03 | .39 | .51 | .79 | .08 | .63 | .96 | .28 | .05 | .19 | .37 |

| MZ | .49 | .05 | .40 | .58 | .84 | .07 | .70 | .98 | .08 | .07 | −.06 | .22 | |

| GFTA-2 Speech | DZ | .51 | .03 | .46 | .57 | .67 | .09 | .49 | .85 | .45 | .04 | .37 | .53 |

| MZ | .54 | .05 | .45 | .63 | .68 | .07 | .55 | .81 | .30 | .07 | .17 | .44 | |

| Mean length of utterance | DZ | .25 | .04 | .18 | .32 | .63 | .18 | .29 | .97 | .15 | .05 | .05 | .25 |

| MZ | .29 | .06 | .17 | .40 | .48 | .10 | .28 | .68 | .06 | .08 | −.09 | .20 | |

| TEGI Composite | DZ | .59 | .03 | .54 | .64 | .85 | .06 | .74 | .95 | .42 | .04 | .33 | .50 |

| MZ | .67 | .04 | .60 | .75 | .82 | .04 | .73 | .90 | .14 | .07 | −.01 | .28 | |

| TEGI Screener | DZ | .52 | .03 | .46 | .58 | .84 | .07 | .71 | .97 | .32 | .05 | .22 | .41 |

| MZ | .61 | .04 | .53 | .70 | .78 | .05 | .68 | .88 | .14 | .08 | −.02 | .29 | |

Note. Est = estimate; LCI = lower 95% confidence interval; UCI = upper 95% confidence interval (truncated at 1); PPVT-3 = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition; TOLD-P:3 = Test of Oral Language Development–Primary: Third Edition; CMMS = Columbia Mental Maturity Scale; GFTA-2 = Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Second Edition; TEGI = Rice–Wexler Test of Early Grammatical Impairment; DZ = dizygotic; MZ = monozygotic.

However, it is important to note that the within-person correlations are an ICC-weighted function of between-pairs and within-pair correlations, as shown in the second and third set of columns in Table 3. The between-pairs (Level 2) correlations indicate the similarity across age of the rank ordering of the twin pairs (i.e., the extent to which pairs who scored higher than other pairs at age 4 also did so at age 6). Thus, this measure captures the extent to which a pair of twins maintains an advantage or disadvantage relative to their age peers. Higher values indicate consistency from 4 to 6 years in either relative advantage or disadvantage. The between-pairs correlations ranged across phenotypes from lows of .63 for DZ twins (for MLU) and .48 for MZ twins (for MLU) to highs of .90 for DZ twins (for TOLD-P:3 Semantics) and .95 for MZ twins (for PPVT-3 Vocabulary). Overall, the “pairedness” level of similarity of twin pairs was consistent across DZ and MZ twin pairs, at moderate to high levels of association, across the two times of measurement. As a pair, twins were unlikely to improve or lose their standing among age peers from 4 to 6 years of age. Last, the within-pair (Level 1) correlations indicate the similarity across age of a child's score relative to his or her own twin (i.e., the extent to which a child who scored higher than his or her twin at age 4 also did so at age 6). The within-pair correlations ranged across phenotypes from lows of .15 for DZ twins (for MLU) and .04 for MZ twins (for PPVT) to highs of .45 for DZ twins and .30 for MZ twins (both for GFTA-2 Speech). Note that if the two members of a twin pair have similar scores, this would work against a similarity in differences between the twins over time, and within the MZ twin pairs, the children are more similar in scores than within the DZ twin pairs. Consistent with this notion, the DZ within-pair correlations are uniformly higher than the MZ within-pair correlations.

Conditional Models: ICCs and Heritability Estimates

Table 4 provides conditional model ICCs for each phenotype by age and zygosity—these ICCs reflect the proportion of total variance attributable to pair-level random intercept variation (i.e., that is due to mean differences between twin pairs). The ICCs ranged across phenotypes from lows of .17 for DZ twins (for MLU) and .46 for MZ twins (for TOLD-P:3 Semantics) to highs of .54 for DZ twins and .81 for MZ twins (both for TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language). As expected from previous research, the ICCs were consistently higher for MZ than DZ twins: For the MZ twins, 13 ICCs were > .60, whereas none were for the DZ twins. ICC differences between MZ and DZ twins ranged across phenotypes from a low of .05 (for TOLD-P:3 Semantics) to a high of .46 (for TEGI Composite); 16 of the 18 ICCs were significantly higher for MZ than DZ twins. The pattern indicates greater common variance for MZ than DZ twins (or equivalently, greater correlation within pairs of MZ than DZ twins), generalizing across multiple phenotypes of speech and language.

Table 4.

Conditional model intraclass correlations by phenotype, age, and zygosity.

| Phenotype | Age | Zygosity | Est | SE | Lower CI | Upper CI | Age difference | Zygosity difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPVT-3 Vocabulary | 4 | DZ | .48 | .04 | .41 | .56 | ||

| MZ | .58 | .05 | .49 | .68 | ||||

| 6 | DZ | .40 | .04 | .32 | .48 | * | ||

| MZ | .67 | .04 | .59 | .75 | ||||

| TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language | 4 | DZ | .54 | .04 | .47 | .61 | * | |

| MZ | .74 | .03 | .68 | .81 | ||||

| 6 | DZ | .46 | .04 | .38 | .54 | * | ||

| MZ | .81 | .03 | .76 | .86 | ||||

| TOLD-P:3 Semantics | 4 | DZ | .41 | .04 | .33 | .50 | ||

| MZ | .46 | .06 | .34 | .58 | * | |||

| 6 | DZ | .33 | .05 | .24 | .41 | * | ||

| MZ | .68 | .04 | .60 | .75 | * | |||

| TOLD-P:3 Syntax | 4 | DZ | .48 | .04 | .41 | .56 | * | |

| MZ | .75 | .03 | .69 | .82 | ||||

| 6 | DZ | .44 | .04 | .36 | .52 | * | ||

| MZ | .78 | .03 | .72 | .83 | ||||

| CMMS Nonverbal IQ | 4 | DZ | .38 | .04 | .29 | .46 | ||

| MZ | .48 | .06 | .37 | .60 | ||||

| 6 | DZ | .29 | .05 | .20 | .38 | * | ||

| MZ | .59 | .05 | .49 | .68 | ||||

| GFTA-2 Speech | 4 | DZ | .35 | .05 | .26 | .44 | * | |

| MZ | .65 | .05 | .56 | .74 | ||||

| 6 | DZ | .25 | .05 | .15 | .34 | * | ||

| MZ | .60 | .05 | .51 | .70 | ||||

| Mean length of utterance | 4 | DZ | .25 | .05 | .15 | .35 | * | |

| MZ | .61 | .05 | .52 | .71 | ||||

| 6 | DZ | .17 | .05 | .07 | .26 | * | ||

| MZ | .48 | .06 | .37 | .59 | ||||

| TEGI Composite | 4 | DZ | .52 | .04 | .44 | .59 | * | * |

| MZ | .79 | .03 | .73 | .85 | ||||

| 6 | DZ | .34 | .04 | .25 | .42 | * | * | |

| MZ | .80 | .03 | .74 | .85 | ||||

| TEGI Screener | 4 | DZ | .49 | .04 | .42 | .57 | * | * |

| MZ | .81 | .03 | .76 | .87 | * | |||

| 6 | DZ | .31 | .05 | .22 | .40 | * | * | |

| MZ | .68 | .04 | .60 | .76 | * |

Note. Est = estimate; CI = confidence interval; PPVT-3 = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition; TOLD-P:3 = Test of Oral Language Development–Primary: Third Edition; CMMS = Columbia Mental Maturity Scale; GFTA-2 = Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Second Edition; TEGI = Rice–Wexler Test of Early Grammatical Impairment; DZ = dizygotic; MZ = monozygotic.

p < .01.

Finally, Table 5 provides the results with respect to the heritability of each phenotype at each age (RQ4) based on the variance components from the previously reported conditional models (see Guo & Wang, 2002). We estimated the proportion of variability in each phenotype attributable to shared genes (h 2 heritability), environmental effects common to the twin pair (c 2 common environment), and environmental factors unique to each twin (e 2 unique environment). Heritability (h 2) can be found as twice the difference of the ICC between MZ and DZ twins. Common environment (c 2) can be found as the difference between the ICC for MZ twins and the heritability estimate (constrained to be ≥ 0), and the unique environment can be found as the remainder (i.e., 1 − heritability + common environment). Note that under this formulation any twinning effects would increase c 2. The estimates, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals for each source of variance are shown for each phenotype in Table 5. The proportions of variance attributable to heritability (h 2) ranged from a low of .10 (TOLD-P:3 Semantics at age 4) to a high of .92 (TEGI Composite at age 6). Significantly greater heritability was found at age 6 than age 4 for three phenotypes: TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language, TOLD-P:3 Semantics, and TEGI Composite. The proportions of variance attributable to common environment (c 2) ranged from 0 to .38, in which zero values are the result of large differences in ICCs between DZ and MZ twins (i.e., as shown in Table 5).

Table 5.

Conditional model heritability and age differences (AD) by phenotype and age.

| Phenotype | Age |

h

2 Heritability |

c

2 Common environment |

e

2 Unique environment |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | LCI | UCI | AD | Est | SE | LCI | UCI | Est | SE | LCI | UCI | ||

| PPVT-3 Vocabulary | 4 | .20 | .13 | .00 | .45 | .38 | .09 | .20 | .56 | .42 | .05 | .32 | .51 | |

| 6 | .54 | .12 | .32 | .77 | .13 | .09 | .00 | .31 | .33 | .04 | .25 | .41 | ||

| TOLD-P:3 Spoken Language | 4 | .40 | .10 | .21 | .59 | * | .34 | .08 | .19 | .50 | .26 | .03 | .19 | .32 |

| 6 | .70 | .09 | .52 | .88 | .11 | .08 | .00 | .27 | .19 | .03 | .14 | .24 | ||

| TOLD-P:3 Semantics | 4 | .10 | .15 | .00 | .39 | * | .37 | .11 | .16 | .57 | .54 | .06 | .42 | .66 |

| 6 | .70 | .12 | .47 | .94 | .00 | .10 | .00 | .17 | .30 | .04 | .22 | .38 | ||

| TOLD-P:3 Syntax | 4 | .54 | .10 | .34 | .74 | .22 | .08 | .05 | .38 | .25 | .03 | .18 | .31 | |

| 6 | .67 | .10 | .48 | .86 | .11 | .09 | .00 | .27 | .22 | .03 | .17 | .28 | ||

| CMMS Nonverbal IQ | 4 | .21 | .15 | .00 | .50 | .27 | .11 | .06 | .48 | .52 | .06 | .40 | .63 | |

| 6 | .59 | .13 | .33 | .85 | .00 | .10 | .00 | .20 | .41 | .05 | .32 | .50 | ||

| GFTA-2 Speech | 4 | .60 | .13 | .35 | .85 | .05 | .10 | .00 | .24 | .35 | .05 | .27 | .44 | |

| 6 | .72 | .13 | .46 | .98 | .00 | .11 | .00 | .09 | .28 | .05 | .19 | .37 | ||

| Mean length of utterance | 4 | .73 | .14 | .46 | 1.00 | .00 | .11 | .00 | .10 | .27 | .05 | .18 | .37 | |

| 6 | .63 | .15 | .34 | .93 | .00 | .11 | .00 | .07 | .37 | .06 | .26 | .48 | ||

| TEGI Composite | 4 | .54 | .10 | .35 | .74 | * | .24 | .08 | .08 | .41 | .21 | .03 | .15 | .27 |

| 6 | .92 | .11 | .71 | 1.00 | .00 | .09 | .00 | .06 | .08 | .03 | .03 | .13 | ||

| TEGI Screener | 4 | .64 | .10 | .45 | .83 | .17 | .08 | .01 | .34 | .19 | .03 | .13 | .24 | |

| 6 | .73 | .12 | .49 | .97 | .00 | .10 | .00 | .14 | .27 | .04 | .19 | .35 | ||

Note. Negative c 2 estimates were replaced with 0. Est = estimate; LCI = lower 95% confidence interval (truncated at 0); UCI = upper 95% confidence interval (truncated at 1); PPVT-3 = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition; TOLD-P:3 = Test of Oral Language Development–Primary: Third Edition; CMMS = Columbia Mental Maturity Scale; GFTA-2 = Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Second Edition; TEGI = Rice–Wexler Test of Early Grammatical Impairment.

p < .01.

Discussion

For our first question, we evaluated nine different age-appropriate language and speech phenotypes with age-referenced scores to see if twinning effects persist beyond the 24-month age level, in which they were previously documented, to ages 4 and 6 years (Rice et al., 2014). For our second question, we investigated whether zygosity effects persist as well, such that the twinning effects are more evident in MZ twins. As reported in Table 1, the twinning effect persists across multiple language phenotypes, although it is not present for speech development. The good news is that the children's performance, relative to their age peers, improves from 4 to 6 years, across multiple language and nonverbal cognitive phenotypes, with the notable exception of a significant drop in speech acquisition relative to age of peers between 4 and 6 years. This drop in speech scores is likely attributable to the psychometric properties of speech acquisition, such that a few developmental speech errors that persist to 6 years is enough for a child to lose ground relative to his or her age peers, even though the child may outgrow the errors in a short time.

There is also good news about zygosity effects, given that, in this time frame, the few statistically significant zygosity effects at age 4 were no longer significant differences at age 6. These outcomes suggest that twin type differences (MZ vs. DZ) seem to resolve by 6 years of age. The ways in which twin children differ from single-born children in their readiness for early stages of language acquisition are reduced considerably or no longer evident at 6 years of age. In effect, the picture is that, on average, they outgrow much of the twinning effect between 4 and 6 years, and the disadvantage for the MZ twins with regard to language and speech acquisition is largely erased. One implication is that, to the extent that a twinning effect complicates the identification of preschool children with language impairments relative to age expectations, there is evidence that this complication is reduced between 4 and 6 years of age.

The third question led to the development of statistical models of predictor effects including twin pair–level predictors (maternal education, maternal age) and individual twin–level predictors (sex, within-occasion age deviation, birth weight, 1- and 5-min APGAR scores) for the nine speech, language, and nonverbal cognition phenotypes. This approach recognizes the complexity of evaluating the speech, language, and cognitive development of twins. Twins bring an unusual social pairing of children, shared effects in the home, biological similarities, and differences within the pair and as compared to single-born children. This is especially important in the context of a longitudinal study in the 4- to 6-year age range, when children are developing rapidly in the phenotypes of interest. Among the predictors of language and speech phenotypes, three stand out as predictors across multiple phenotypes: Maternal education, maternal age, and child sex. The two maternal variables are of interest because they may contribute in different ways to children's development. In the developmental psychology literature, maternal education is conventionally viewed as a proxy variable for the ways in which a home provides social and cognitive experiences that facilitate language and cognitive development (Entwisle & Astone, 1994). Maternal age is considered to be a biological predictor of perinatal outcomes, such as birth weight (Blair et al., 2005; Liu & Blair, 2002). In the context of heritability estimates, these three variables could work against estimates of heritability if they are on the genetic causal pathway for the phenotypes or reduce estimates of heritability if they influence environmental effects. Birth weight could also work against estimates of heritability. Most of the significant modeling outcomes were differences in weight within pairs at ages 4 and 6. Such within-pair differences in twins could be viewed as e 2 effects that would reduce heritability estimates.

Further complications arise if maternal education is viewed as an SES marker. A recent study using a genome-wide complex trait analysis on DNA from unrelated individuals reports the association between family SES and children's cognitive development is not an environmental effect alone. Instead, there is substantial genetic mediation by genetic factors (Trzaskowski et al., 2014). Because twin children share family SES and mother's education, twin methods may be insensitive to genetic influence on family SES or potential Gene × Environment interactions. If so, it would be an oversimplification to interpret the significant prediction of maternal education on children's language acquisition as an environmental influence but instead a predictor confounded with genetic influence as well.

Heritability estimates were obtained in conditional models after controlling for the aforementioned predictors. Keep in mind that any twinning effects would work against h 2 estimates, given that twinning effects increase correlations within families for both MZ and DZ pairs, thus raising shared environment estimates. The outcomes support the prediction of heritable influences on children's language acquisition. Table 5 indicates strong replication at age 6 of heritability of .5 or above across the phenotypes. Across the phenotypes, one stood out as higher than the others; the TEGI composite had an h 2 of .92. This is consistent with a previous report from the TEDS sample of twins (Bishop, Adams, & Norbury, 2006), which used a combined score of two prepublication subtests from TEGI (past tense and third-person singular -s) as a phenotype, which they called “tense marking.” The TEGI composite score is highly correlated with the combined score of these two subtests. Each of these phenotypes would be assessing the finiteness-marking property of grammar. They reported higher heritability and distinct genetic influences on this grammar clinical marker, as compared to a nonword repetition phenotype, in a study of children with language impairments. It is also consistent with the optional infinitive hypothesis proposed by Wexler (Wexler, 1996, 2003), predicting genetic influences on certain parts of the grammar. It must be noted that age 6 years is in the age range where this particular phenotype has high sensitivity to individual differences in children's acquisition of grammar. It is not psychometrically informative beyond 8;11 years of age (Rice & Wexler, 2001), although there is evidence that another measure of this domain of grammar, involving grammatical judgments of questions, does detect persistent individual differences into adolescence (Rice, Hoffman, & Wexler, 2009).

Similarity in phenotypes from the earlier study of 24-month twins (Rice et al., 2014) and similar modeling methods across the earlier study and this study allow for comparison of heritability within and across language dimensions across the ages of children. The vocabulary heritability at 24 months was .26 (c 2 = .71); at 4, for the PPVT, .20 (c 2 = .38); and at 6, .54 (c 2 = . 13). For finiteness marking, the heritability at 24 months differed by gender, with .52 (c 2 = .36) for boys and .43 (c 2 = .50) for girls. Heritability of finiteness marking on TEGI was .54 (c 2 = .24) at 4 years and .92 (c 2 = 0) at 6 years.

Another observation is that the outcomes replicate several findings in the literature with respect to the etiology of different aspects of language at the ages of interest here. The high heritability of finiteness marking, increasing with age, as measured by TEGI, is very striking and consistent with the strong hint of heritability in this dimension from the 24-month twin study, which found strong heritability for early emergence of finiteness marking in the simple sentences of young children (Rice et al., 2014). In a similar pattern, the speech phenotype had high heritability, increasing with age, with some nonshared environment (and no shared environment). In contrast, vocabulary/semantics shows a markedly different pattern, with substantial shared environmental effects in preschoolers, which diminish as genetic effects increase after age 4, which is consistent with outcomes from TEDS and the International Longitudinal Twin Study (Olson et al., 2011).

One of the limitations of this study is a relatively small sample size for a twin study. This limitation is offset by the multiple phenotypes measuring the domains of language and speech acquisition (providing evidence of replication across measures), repeated measures at 4 and 6 years of age, and the analytic power of general linear mixed models with relevant covariates and all individual twins in the models. Another possible design would be a comparison with a population-based sample of singleton children. In the study reported here, the normative data from the standardized assessments provided standard scores calculated to take into account variance around age-level means. An alternative approach was followed in an earlier study (Rutter, Thorpe, Greenwood, Northstone, & Golding, 2003) of a sample of 96 twin pairs at 36 months comparing twin pairs to singleton pairs. The primary language outcome was reported as an average of 3.1 months advantage for singletons compared to twins at 36 months, although the mean score for the twins was 1.5 months over the test norms and the mean score for the singletons was 4.7 months over test norms; performance on another language assessment showed the same pattern of higher than expected performance levels for the singleton sample and performance for the twins at age expectations for the assessment. It is not possible to compare these metrics of difference to the standard scores reported in this study, in which the means are adjusted for variance around the means for stable psychometric comparisons across age. The age-in-months scores are the mean scores for the age levels, unadjusted for variance, which can differ across ages. The months of difference may be within measurement error of the assessments or insensitive to actual differences from the population means for the assessments.

Conclusion

This study features the first epidemiologically ascertained sample of 4- and 6-year-old twins for whom there is direct behavioral assessment of a comprehensive battery of speech, language, and nonverbal cognition age-adjusted phenotypes. It is also the first report of the methods of general linear mixed models for phenotypes of direct assessments of children at ages 4 and 6 years. Perhaps because of more precisely measured phenotypes, the heritability estimates are higher than those reported earlier for children with phenotypes based on parental questionnaires and web-based short-form assessments (Hayiou-Thomas et al., 2012).

The key conclusions from this study are as follows:

Twinning effects evident at 2 years decreased between 4 and 6 years of age, with the exception of speech scores at 6 years of age. This suggests that, for some of the more difficult speech sound combinations, the twin sample is not progressing quite as fast as expected for their age.

By age 6, zygosity effects are no longer evident in any of the nine phenotypes.

The effects of covariates were minimal.

The heritability estimates at age 6 exceeded .5 for all nine of the phenotypes and were highest for the clinical grammar marker at age 6, with an estimate of .92.

All in all, the outcomes suggest that some of the special features of twins relevant for early language acquisition comprise less of the picture by 6 years of age, when speech, language, and nonverbal cognitive development demonstrates robust indications of heritable effects. In this broad domain, indications of an inherited effect on the finiteness marking requirement in grammar stands out as especially robust.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH R01DC005226 (Rice, Zubrick, and Taylor as PIs). Preparation of this paper was supported by NIH R01DC001803 (Rice, PI), NIH P30DC005803 (Rice, PI), NIH R42DC013749 (Rice as co-PI), and NIH P30HD002528 (Rice as affiliated researcher). Zubrick and Taylor were supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council (CE140100027).

The authors especially thank the children and families who participated in the study and the following members of the research team: Sarah Beveridge-Pearce, Bradley Calamel, Tanya Dickson, Julie Fedele, Lucy Giggs, Antonietta Grant, Jennifer Hafekost, Erika Hagemann, Jessica Hall, Anna Hunt, Alicia Lant, Stephanie McBeath, Megan McClurg, Alani Morgan, Virginia Muniandy, Elke Scheepers, Elke, Leanne Scott, Michaela Stone, and Kerry Van de Pol. The authors also thank Denise Perpich for data management and preliminary data summaries and the staff at the Western Australian Data Linkage Branch and the Maternal and Child Health Unit.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by NIH R01DC005226 (Rice, Zubrick, and Taylor as PIs). Preparation of this paper was supported by NIH R01DC001803 (Rice, PI), NIH P30DC005803 (Rice, PI), NIH R42DC013749 (Rice as co-PI), and NIH P30HD002528 (Rice as affiliated researcher). Zubrick and Taylor were supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council (CE140100027).

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2001). 2001 Census of Population and Housing - SEIFA 2001. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D., Adams C. V., & Norbury C. F. (2006). Distinct genetic influences on grammar and phonological short-term memory deficits: evidence from 6-year-old twins. Genes, Brain, and Behavior, 5(2), 158–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair E., Liu Y., de Klerk N., & Lawrence D. (2005). Optimal fetal growth for the Caucasian singleton and assessment of appropriateness of fetal growth: Analysis of a total population perinatal database. BMC Pediatrics, 5, 1471–2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgemeister B. B., Blum L. H., & Lorge I. (1972). The Columbia Mental Maturity Scale. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Dale P. S., Dionne G., Eley T. C., & Plomin R. (2000). Lexical and grammatical development: A behavioural genetic perspective. Journal of Child Language, 27, 619–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale P. S., Simonoff E., Bishop D. V. M., Eley T. C., Oliver B., Price T. S., … Plomin R. (1998). Genetic influence on language delay in two-year-old children. Nature Neuroscience, 1, 324–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeThrone L. S., Harlaar N., Petrill S. A., & Deater-Deckard K. (2012). Longitudinal stability in genetic effects on children's conversational language productivity. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55, 739–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L. M., & Dunn L. M. (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle D. R., & Astone N. M. (1994). Some practical guidelines for measuring youths' race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Child Development, 65(6), 1521–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Gee V., & Green T. (2004). Perinatal statistics in Western Australia, 2003: Twenty-first annual report of the Western Australian Midwives’ Notification System. Retrieved from Perth, Western Australia. Retrieved from http://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/

- Goldman R., & Fristoe M. (2000). Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Second Edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Guo G., & Wang J. (2002). The mixed or multilevel model for behavior genetic analysis. Behavior Genetics, 32(1), 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J., Alessandri P., Croft M., Burton P., & de Klerk N. (2004). The Western Australian register of childhood multiples: Effects of questionnaire design and follow-up protocol on response rates and representativeness. Twin Research, 7(2), 149–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayiou-Thomas M. E. (2008). Genetic and environmental influences on early speech, language and literacy development. Journal of Communication Disorders, 41, 397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayiou-Thomas M. E., Dale P. S., & Plomin R. (2012). The etiology of variation in language skills changes with development: A longitudunal twin study of language from 2 to 12 years. Developmental Science, 15(2), 233–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayiou-Thomas M. E., Dale P. S., & Plomin R. (2014). Language impairment from 4 to 12 years: Prediction and etiology. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57, 850–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayiou-Thomas M. E., Kovas Y., Harlaar N., Plomin R., Bishop D. V. M., & Dale P. S. (2006). Common aetiology for diverse language skills in 4 1/2-year-old twins. Journal of Child Language, 33(2), 339–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L. (2015). Longitudinal analysis: Modeling within-person fluctuation and change. New York, NY: Routledge Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Kovas Y., Hayiou-Thomas M. E., Oliver B., Dale P. S., Bishop D. V. M., & Plomin R. (2005). Genetic influences in different aspects of language development: The etiology of language skills in 4.5-year-old twins. Child Development, 76, 632–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. C., & Blair E. M. (2002). Predicted birthweight for singletons and twins. Twin Research, 5(6), 529–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J., & Chapman R. (2002). SALT for Windows. Standard version 7.0. Madison, WI: Language Analysis Laboratory, Waisman Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., & Muthén B. O. (1998–2015). Mplus user's guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Authors. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer P., & Hammill D. (1997). Test of Oral Language Development–Primary: Third Edition (TOLD-P:3-P:3). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver B. R., & Plomin R. (2007). Twins Early Development Study (TEDS): A multivriate, longitudinal genetic investigation of language, cognition and behavior problems from childhood through adolescence. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 10, 96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson R. K., Keenan J. M., Byrne B., Samuelsson S., Coventry W. L., Corley R., … Hulslander J. (2011). Genetic and environmental influences on vocabulary and reading development. Scientific Studies of Reading: The Official Journal of the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading, 20(1–2), 51–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-006-9018-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice M. L., Hoffman L., & Wexler K. (2009). Judgments of omitted BE and DO in questions as extended finiteness clinical markers of specific language impairment (SLI) to 15 years: A study of growth and asymptote. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 1417–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice M. L., Redmond S. M., & Hoffman L. (2006). MLU in children with SLI and young control children shows concurrent validity, stable and parallel growth trajectories. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49, 793–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice M. L., Smolik F., Perpich D., Thompson T., Rytting N., & Blossom M. (2010). Mean length of utterance levels in 6-month intervals for children 3 to 9 years with and without language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice M. L., Taylor C. L., & Zubrick S. R. (2008). Language outcomes of 7-year-old children with or without a history of late language emergence at 24 months. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(2), 394–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice M. L., & Wexler K. (2001). Test of Early Grammatical Impairment. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Rice M. L., Zubrick S. R., Taylor C. L., Gayán J., & Bontempo D. E. (2014). Late language emergence in 24 month twins: Heritable and increased risk for twins. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57, 917–928. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0350) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M., Thorpe K., Greenwood R., Northstone K., & Golding J. (2003). Twins as a natural experiment to study the causes of mild language delay: I: Design; twin-singleton differences in language, and obstretric risks. Journal of Child Psychlogy and Psychiatry, 44(3), 326–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. (2017). Base SAS 9.4 procedures guide: Statistical procedures (5th ed.). Cary, NC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T. A. B., & Bosker R. (2012). Multilevel analysis (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Trzaskowski M., Harlaar N., Arden R., Krapohl E., Rimfeld K., McMillan A., … Plomin R. (2014). Genetic influence on family socioeconomic status and children's intelligence. Intelligence, 42, 83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler K. (1996). The development of inflection in a biologically based theory of language acquisition. In Rice M. L. (Ed.), Toward a genetics of language (pp. 113–144). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler K. (2003). Lenneberg's dream: Learning, normal language development and specific language impairment. In Levy Y. & Schaeffer J. (Eds.), Language competence across populations: Toward a definition of specific language impairment (pp. 11–62). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Zubrick S. R., Taylor C. L., Rice M. L., & Slegers D. (2007). Late language emergence at 24 months: An epidemiological study of prevalence, predictors, and covariates. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 1562–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]