Abstract

Objective

To determine whether a soft cervix identified by shear-wave elastography between 18-24 weeks of gestation is associated with increased frequency of spontaneous preterm delivery (sPTD).

Methods and Methods

This prospective cohort study included 628 consecutive women with a singleton pregnancy. Cervical length (mm) and softness [shear-wave speed: (SWS) meters per second (m/s)] of the internal cervical os were measured at 18-24 weeks of gestation. Frequency of sPTD <37 (sPTD <37) and <34 (sPTD <34) weeks of gestation was compared among women with and without a short (≤ 25mm) and/or a soft cervix (SWS <25th percentile).

Results

There were 31/628 (4.9%) sPTD < 37 and 12/628 (1.9%) sPTD < 34 deliveries. The combination of a soft and a short cervix increased the risk of sPTD < 37 by 18-fold [relative risk (RR) 18.0 (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.7–43.9); P < 0.0001] and the risk of sPTD < 34 by 120-fold [RR 120.0 (95% CI 12.3–1009.9); P < 0.0001] compared to women with normal cervical length. A soft-only cervix increased the risk of sPTD < 37 by 4.5-fold [RR 4.5 (95% CI 2.1–9.8); P = 0.0002] and of sPTD < 34 by 21-fold [RR 21.0 (95% CI 2.6–169.3); P = 0.0003] compared to a non-soft cervix.

Conclusion

A soft cervix at 18–24 weeks of gestation increases the risk of sPTD <37 and <34 weeks of gestation independently of cervical length.

Keywords: Acoustic radiation force impulse, cervical stiffness, dynamic elastography, preterm labor, short cervix, ultrasound

Introduction

A short cervix identified before 24 weeks of gestation is associated with a higher risk of preterm delivery (PTD) [1–9]. Treatment with vaginal progesterone reduces the incidence of PTD in these patients by 40% and in the neonatal morbidity and mortality of their offspring [10–16]; nevertheless, a considerable number of women will still deliver preterm.

Other cervical characteristics, such as cervical softness, might be informative about the risk of PTD [17–19]. Changes in cervical softness are related to the visco-elastic properties of the cervix that, in turn, are determined by the collagen content and structure (e.g. reduced cross-links) of the cervix and by the water content and concentration of proteoglycans in the extracellular matrix [20–25]. Sundtoft et al. [26] found that the collagen content of the cervix in cervical biopsies was significantly lower in women who had a short cervix or cervical incompetence in a pregnancy 1 year prior to the biopsy than in women who had a normal cervix.

Ultrasound elastography has been used to estimate the elastic properties of tissues [27–31]. Among different elastography modalities [32], two methods are mainly used: (1) quasistatic or strain elastography, where a mechanical force is manually applied to create the displacement of tissues; and (2) shear-wave elastography, where an acoustic force creates a mechanical impulse that generates tissue displacement in the form of shear-waves [33, 34]. Elastography techniques have been used to evaluate malignancies in the breast [35–40], prostate [41] and thyroid gland [42, 43] in women with fibroids [44] as well as in patients with liver disease [45].

Early attempts to sonographically assess cervical elasticity were performed using strain elastography, which suffered from a disadvantage: the mechanical force required to displace the cervix could not be standardized [46]. Nevertheless, by using this technique, investigators demonstrated that induction of labor was more successful in women who had a “soft” cervix, and it established an association between strain in the cervix and PTD [47–55].

Shear-wave elastography has overcome the limitations of strain elastography by automatically generating an acoustic force to displace the cervix that can be measured as speed in meters per second (m/s) or as an indirect estimate of Young’s modulus of elasticity in kilopascals [56–58]: the lower the shear-wave speed (SWS), the “softer” the cervix. Previous studies using shearwave elastography yielded encouraging results [59, 60]. Indeed, Carlson et al. [61] showed that treatment of nonpregnant cervices with prostaglandins, and induction of labor with prostaglandins, reduced the SWS in the cervix. Muller et al. [62] found that SWS was significantly reduced in women who had symptoms of preterm labor and who delivered preterm. Peralta et al. [63] reported that SWS in the cervix of pregnant ewes was progressively reduced during cervical ripening with dexamethasone. However, the question of whether cervical softness in asymptomatic women at the midtrimester can be used for the identification of patients at risk of subsequent spontaneous preterm birth is still unanswered.

Encouraged by these results, and our own early experience with strain elastography [52, 64], we addressed this question by studying a cohort of unselected women with shear-wave elastography in the midtrimester to determine whether cervical SWS can provide clinically useful information about the risk of subsequent spontaneous preterm delivery (sPTD).

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This study included an unselected cohort of 633 consecutive women with a singleton pregnancy who underwent a vaginal ultrasound examination for cervical length and shear-wave elastography between 18 and 24 weeks of gestation. The study was conducted at the Center for Advanced Obstetrical Care and Research (CAOCR) of the Perinatology Research Branch (PRB) of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS), which is housed at Hutzel Women’s Hospital and Wayne State University (WSU) School of Medicine, Detroit, MI, USA. All women were recruited onto protocols approved by the Human Investigation Committee of WSU and the Institutional Review Board of NICHD, and they provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Demographic characteristics, details of prenatal testing, labor and delivery and neonatal outcome were recorded for each patient. Gestational age was confirmed by ultrasound, and gestational age at delivery was calculated and recorded for each participant. PTD was defined as spontaneous preterm labor and delivery <34 and <37 weeks of gestation. Women found to have a short cervix on vaginal ultrasound, defined as a cervical length ≤25 mm, were treated with vaginal progesterone daily until 37 weeks of gestation or until delivery [11, 12].

Ultrasound examination

The cervix was examined using a transvaginal 12-3 MHz ultrasound endocavitary probe (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix-en-Provence, France), and the cervical length measured as previously suggested [65, 66]. Three sonographers, each of whom had more than 3 years of experience in strain and shear-wave cervical elastography, performed the cervical SWS and cervical length estimations [17].

To measure cervical SWS, cross-sectional images of the internal and external os were obtained by rotating the ultrasound probe through 90° and adjusting the elastogram box to cover the entire cross-sectional image of the cervix: cross-sectional cervical images allow better alignment between the ultrasound probe and the region to be studied [64, 67]. Minimal pressure was applied to the cervix while the ultrasound probe was kept in a fixed position to ensure that the size of the anterior and posterior cervical lips remained the same, while the patient was asked to hold her breath for a very short period of time.

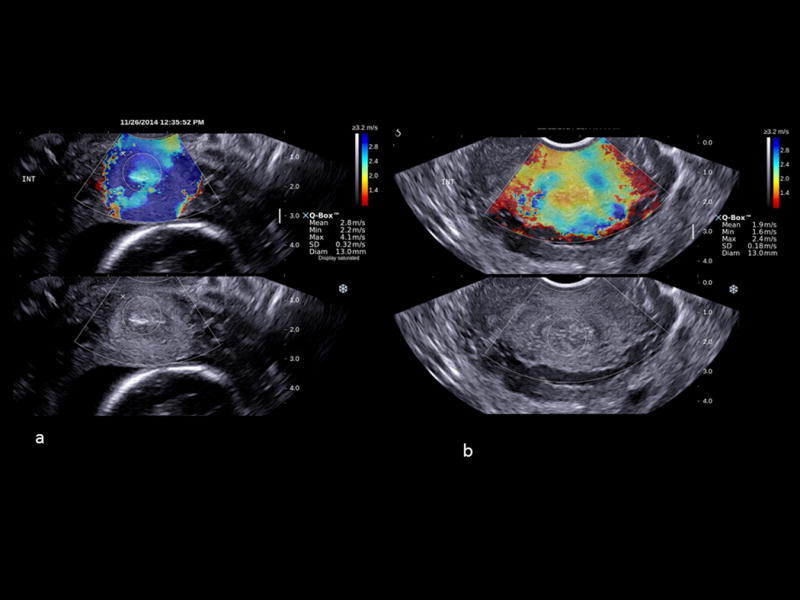

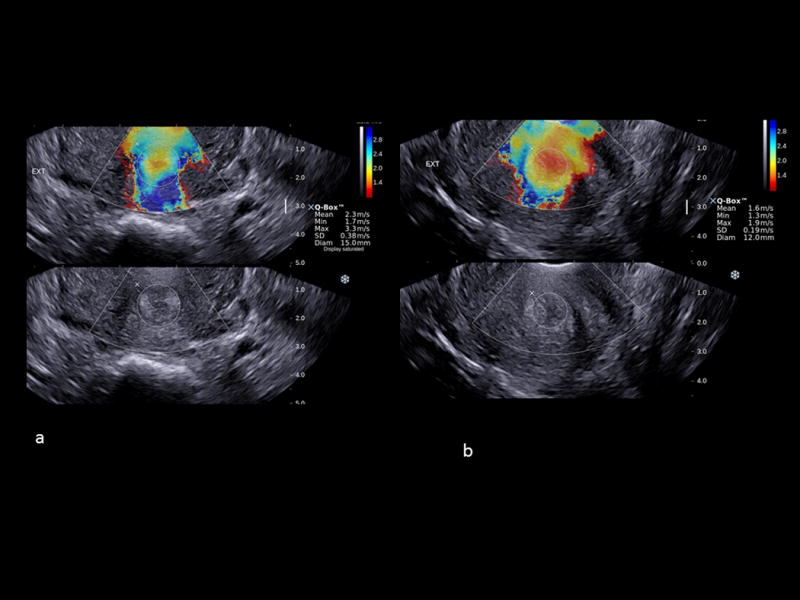

Elastography was initiated after the anatomical plane of the internal (Figure 1) or external os (Figure 2) was identified, whereupon the system automatically generated an acoustic impulse and estimated the SWS. Areas that were stiff had high SWS and appear in blue, whereas soft areas had low SWS and appear in red on the elastogram [34]. SWS, expressed as m/s, was calculated using a circular region of interest (Q-box) adjusted to include the entire cervix, and the mean of three consecutive images was taken as the patient’s cervical SWS. The obtained shear-wave speed values were specific for those two regions of the cervix. Elastogram images were used only if the standard deviation of the SWS within the region of interest was ≤30% of the mean [62, 63]. Data from five patients failed to meet this criterion, and they were excluded from the analysis, which was based on 628 patients.

Figure 1.

Shear-wave elastography in a cross-sectional plane of the internal cervical os from two patients at 19 weeks of gestation; a) a non-soft cervix (shear-wave speed (SWS) = 2.8 m/s [SWS 25th percentile =2.48 m/s]); b) a soft cervix with an SWS of 1.9 m/s (≤25th percentile). High SWS is shown in blue and low SWS in red.

Figure 2.

Shear-wave elastography in the cross-sectional planes of the external cervical os of two patients at 21 weeks of gestation; a) a non-soft cervix (shear wave speed (SWS) = 2.3 m/s [SWS 25th percentile= 1.72 m/s]); b) a soft cervix with a SWS of 1.6 m/s (≤25th percentile). High SWS is shown in blue and low SWS in red.

The 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles of SWS in the internal and external cervical os were calculated for each gestational week in the period spanning the study (18–24 weeks). A “soft” cervix was defined by an SWS <25th centile for gestational age at which elastography was performed.

Statistical analysis

Least-square multiple regression was used to examine the effects of ethnicity, maternal age, body mass index (BMI), obstetrical history and cervical length (expressed as a continuous variable) on SWS. Logistic regression was used to examine the effect of continuous variables (BMI, maternal age) on the probability of having a short or a soft cervix. Variance inflation factors (VIF) were estimated to ensure that co-linearity among variables did not affect the reliability of the estimation of the coefficients in the logistic regression model. The effects of parity, prior PTD, cervical length dichotomized as short (≤25 mm) and not short (>25 mm), cervical softness dichotomized as soft (SWS <25th centile for gestational age) and not soft (SWS ≥25th centile for gestational age), and their interactions on the risk (incidence) of sPTD <34 and <37 weeks were examined by fitting hierarchically nested log linear models to multi-way contingency tables of the data. Relative Risks were estimated using the Poisson regression model with robust estimation of the variance structure. Two-tailed Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare simple differences between proportions and 2 × 2 marginal tables. Values for statistics below the 5% significance level were accepted as statistically significant. The analyses were carried out using the R statistical language and environment (www.r-project.org).

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics and other relevant parameters for the 628 women who had an elastogram examination of the cervix. Most women were of African-American ethnicity (571/628, 91.2%) and were nonsmokers (543/628, 86.5%); 43.9% of them (276/628) had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2.

Table 1.

Demographic and other relevant statistics of the study population

| Study population N = 628 |

|

|---|---|

| Mean age, years (range) | 24 (15-41) |

| Mean BMI (range) | 28.9 (15.2-59.3) |

| Body mass index >30 Kg/m2 | 276 (43.9%) |

| African-American ethnicity (N) | 571 (91.4%) |

| Smokers (N) | 85 (13.5%) |

| First pregnancy (N) | 125 (19.9%) |

| Spontaneous miscarriages/therapeutic terminations only prior to first delivery (N) | 84 (13.4%) |

| Multipara (N) | 419 (66.7%) |

| Prior history of preterm delivery TD (N) | 116 (18.5%) |

| No prior history of preterm delivery (N) | 303 (48.2%) |

| Short cervix only (N) | 13 (2.1%) |

| Soft cervix only (N) | 150 (23.9%) |

| Short & soft cervix (N) | 15 (2.4%) |

| Neither short nor soft cervix (N) | 450 (71.7%) |

| Delivery ≥37 weeks (N) | 597 (95.1%) |

| Delivery 34-36.6 weeks (N) | 19 (3.0%) |

| Delivery <34 weeks (N) | 12 (1.9%) |

| Mean gestational age at delivery, weeks (range) | 39 (23-41) |

| Mean birthweight, grams (mean, SD) | 3069 (634.3) |

| Small for gestational age (N) | 94 (15.2%) |

| Low 5’ Apgar (<6) score (N) | 23 (3.6%) |

SD, standard deviation

Thirty-three percent (209/628) of the women were nulliparous, 19.9% (125/628) were in their first pregnancy and 13.4% (84/628) had only previous therapeutic abortion or spontaneous miscarriage. The remaining 66.7% (419/628) of the cases were multiparous: 303 (48.3%) had term deliveries (TD), and 165/303 (54.4%) also had one or more miscarriages; 116 (18.5%) had previous PTD, and 49/116 (42.2%) also had one or more previous miscarriages.

Table 2 shows the distribution of SWS at the internal and external cervical os at each gestational age studied. The three consecutive readings averaged to obtain each patient’s SWS varied by 5%–7% of the overall mean. The SWS decreased progressively with gestational age and was significantly higher at the internal than at the external cervical os at each gestational age. The SWS increased significantly with cervical length, but not with maternal age, BMI, smoking status or ethnicity. Eighty-six women showed a soft internal and a soft external cervical os, and six (6.9%) had sPTD < 34 weeks of gestation. The SWS in the external cervical os did not contribute to the prediction of preterm delivery; therefore, a soft cervix was considered only in relation to the SWS observed in the internal cervical os.

Table 2.

Shear-wave speed (SWS, meters/second [m/s]) in the internal and the external cervical os during the study period (18-24 weeks of gestation)

| Internal Cervical Os (SWS m/s) |

External Cervical Os SWS (m/s) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 95th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 95th |

| 18 (n=90) | 1.97 | 2.60 | 3.29* | 3.99 | 4.62 | 1.41 | 1.91 | 2.46 | 3.02 | 3.52 |

| 19 (n=88) | 1.88 | 2.48 | 3.14* | 3.81 | 4.41 | 1.38 | 1.84 | 2.36 | 2.88 | 3.35 |

| 20(n=107) | 1.79 | 2.36 | 3.00* | 3.64 | 4.21 | 1.35 | 1.78 | 2.27 | 2.75 | 3.19 |

| 21 (n=99) | 1.71 | 2.26 | 2.87* | 3.48 | 4.02 | 1.32 | 1.72 | 2.18 | 2.63 | 3.04 |

| 22 (n=85) | 1.64 | 2.16 | 2.74* | 3.33 | 3.85 | 1.29 | 1.67 | 2.10 | 2.52 | 2.91 |

| 23 (n=61) | 1.57 | 2.07 | 2.63* | 3.19 | 3.69 | 1.26 | 1.62 | 2.02 | 2.42 | 2.78 |

| 24 (n=98) | 1.50 | 1.98 | 2.52* | 3.06 | 3.54 | 1.24 | 1.58 | 1.95 | 2.33 | 2.67 |

p<0.001 as compared to the mean SWS in the external cervical os

From the total number of 628 participants: 28 women (4.5%) had a short cervix and 165 (26.3%) a soft cervix, 15 (2.4%) of them had a combination of a short and soft cervix, and 450 (71.7%) had neither. Women with a short cervix were twice as likely to have a soft cervix than women who did not have a short cervix [15/28 (53.4%) vs. 150/600 (25%); relative risk (RR) 2.1 (95% confidence interval, CI 1.5–3.1); P = 0.002]; conversely, women with a soft cervix were 3.2 times more likely to have a short cervix than women who did not have a soft cervix [15/165 (9.1%) vs. 13/463 (2.8%); RR 3.2 (95% CI 1.57–6.66); P = 0.002]. The probability of having a soft cervix increased significantly with maternal age (P = 0.02) but not with BMI (P = 0.87); a 10-year increase in maternal age was associated with a 1.4-fold increase in the probability of having a soft cervix. The probability of having a short cervix did not vary significantly with maternal age or BMI.

Interrelationships between cervical length, cervical softness and past obstetrical history

Table 3 shows the distribution of cervical length and cervical softness according to past obstetrical history. The test for heterogeneity of the data (counting separately those women who had only a short cervix, only a soft cervix, a short and soft cervix, or neither a short nor soft cervix) was significant [chi-square (χ2) = 22.5, df = 15; P = 0.048]. These results were related to the heterogeneous distribution of soft cervices and the combination of short and soft cervices, but not of cervices that were only short or neither short nor soft, among these six groups of women (χ2 = 13.3, df = 5; P = 0.021, and χ2 = 15.6, df = 5; P = 0.008, respectively). The underlying associations were between cervical length and cervical softness and two factors: a prior abortion and a prior PTD.

Table 3.

Distribution of cervical length and cervical softness (shear wave speed [SWS, m/s]) according to past obstetrical history

| Past Obstetrical History | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervix Evaluation | First Pregnancy | Previous Miscarriages Only | Previous Term deliveries Only | Previous Term Deliveries and Miscarriages | Only Previous Spontaneous Preterm Delivery | Previous Spontaneous Preterm Delivery and Miscarriages | Total |

| Short (≤ 25mm) | 2 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 28 |

| Soft (SWS [m/s] < 25th percentile |

23 | 23 | 37 | 42 | 16 | 24 | 165 |

| Short + Soft | 0 | (5) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (1) | (15) |

| Neither | 100 | 59 | 99 | 121 | 31 | 40 | 450 |

| Total | 125 | 84 | 138 | 165 | 49 | 67 | 628 |

Chi-square test for heterogeneity=22.5, df=15, p=0.048. The number in parentheses must be subtracted to obtain the total.

A higher proportion of women who had had only a prior preterm delivery had a short and soft cervix than those in their first pregnancy [4/49 (8.2%) vs. 0/125, RR 22.7 (95% CI 1.2–413.6); P = 0.006] and women who had prior TD [4/49 (8.2%) vs. 2/138 (1.5%), RR 5.6 (95% CI 1.1–29.8); P = 0.04]; the proportion of women who had only a soft cervix was not significantly different among these three groups of women [18/84 (21%) vs. 23/125 (18.4%) vs. 35/138 (25.4%), respectively; P = 0.4]. The proportion of short and soft cervices among women in their first pregnancy and women who had prior TD was also not significantly different.

Table 4 shows the distribution of cervical length and cervical softness among multiparous women stratified by history of prior PTD. There were 419 multiparous women; of these, 116 (27.7%) had a prior PTD. Women who had a short cervix were twice as likely to have a prior PTD than women with a normal cervix [10/28 (35.7%) vs. 106/600 (17.7%), RR 2.0 (95% CI 1.2–3.42); P = 0.009], and women who had a soft cervix were 1.5 times more likely to have had a prior PTD than women who did not have a soft cervix [40/165 (24.3%) vs. 76/463 16.4%), RR 1.5 (95% CI 1.1–2.1); P = 0.03].

Table 4.

Distribution of cervical length and cervical softness among mulitiparous women stratified by a history of prior preterm delivery

| History of prior preterm delivery | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cervix evaluation | Yes | No | Total |

| Short (cervical length ≤ 25 mm) | 10 | 9 | 19 |

| Soft (shear wave speed [m/s] <25th percentile) | 40 | 79 | 119 |

| Short + Soft | (5) | (5) | (10) |

| Neither | 71 | 220 | 291 |

| Total | 116 | 303 | 419 |

The number in parentheses must be subtracted to obtain the total number of cases.

Factors affecting the risk (incidence) of preterm delivery

Table 5 shows the proportion of women who had a short, a soft and the combination of a short and a soft cervix, or neither, and who delivered at term, between 34–36.6 weeks and <34 weeks of gestation, stratified by parity and the type of prior pregnancy and delivery. Thirty-one (4.9%; 31/628) women had a sPTD <37 weeks of gestation (sPTD < 37) and 12 (1.9%; 12/628) had a sPTD <34 weeks of gestation (sPTD < 34).

Table 5.

Preterm deliveries stratified by cervical length, cervical softness, and past obstetrical history

| Delivery | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervix Evaluation | ≥ 37 weeks | 34 – 37 weeks | < 34 weeks | |||||||||||

| Short (≤ 25 mm) |

Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||||||

| Soft (SWS [m/s] <25th percentile) |

Both | No | Yes | No | Both | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Total | |

| 1 | First Pregnancy | 0 | 2 | 22 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 125 |

| 2 | Previous miscarriages only | 1 | 2 | 16 | 58 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 84 |

| 3 | No previous preterm deliveries or miscarriages | 1 | 2 | 31 | 96 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 138 |

| 4 | No previous preterm deliveries and miscarriages | 2 | 2 | 35 | 121 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 165 |

| 5 | Only previous preterm deliveries but no miscarriages | 4 | 2 | 11 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 49 |

| 6 | Previous preterm deliveries and miscarriages | 1 | 3 | 20 | 37 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 67 |

| Total | 9 | 13 | 135 | 440 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 628 | |

Six (21.4%) of the 28 women with a short cervix delivered preterm (four sPTD < 34); all six had a soft cervix, four had prior abortion only and none had a history of prior PTD. None of the 13 women who had only a short cervix delivered preterm. Compared to women who had neither a short nor a soft cervix, women with a short cervix had a 9.6-fold increase in the risk of sPTD < 37 [6/28 (21.4%) vs. 10/450 (2.2%) RR 9.6 (95% CI 3.9–25.2); P < 0.001] and a 64-fold increase in the risk of sPTD < 34 [4/28 (14.3%) vs. 1/450 (0.2%) RR 64.3 (95% CI 7.4–556.2); P < 0.001].

Twenty-one (12.7%) of the 165 women with a soft cervix delivered preterm (21 sPTD < 37; 11 sPTD < 34); six (28.6%) had a short cervix and four had a prior PTD. Compared to women who had neither a short nor a soft cervix, women with a soft cervix had a 5.7-fold increase in the risk of sPTD < 37 [21/165 (12.7%) vs. 10/450 (2.2%) RR 5.7 (95% CI 2.8–11.9); P < 0.001] and a 30-fold increase in the risk of sPTD < 34 [11/165 (6.7%) vs. 1/450 (0.2%) RR 30.0 (95% CI 3.9–230.6); P < 0.001].

Ten (2.2%) of the 450 women who had neither a short nor a soft cervix delivered preterm (nine PTD < 37; one PTD < 34).

Both cervical length and cervical softness had a significant impact on the risk of sPTD < 37 and sPTD < 34, and there was an interaction between their effects on the risk of sPTD < 37 and sPTD < 34. Compared to a cervix that was neither short nor soft, a soft cervix alone significantly increased the risk of PTD < 37 by 4.5-fold [15/150 (10%) vs. 10/450 (2.2%) RR 4.5 (95% CI 2.1–9.8); P ≤ 0.0002] and the risk of PTD < 34 by 21-fold [7/150 (4.6%) vs. 1/450 (0.2%) RR 21.0 (95% CI 2.6–169.3); P < 0.001]; a short cervix alone did not significantly increase the risk of sPTD < 37 [0/13 vs. 10/450 (2.2%); P = 0.75] or of sPTD < 34 [0/13 vs. 1/450 (0.2%)], but a short and soft cervix increased the risk of sPTD < 37 by 18-fold [6/15 (40%) vs. 10/450 (2.2%) RR 18.0 (95% CI 7.7–43.9); P < 0.0001], and the risk of sPTD < 34 by 120-fold [4/15 (26.7%) vs. 1/450 (0.2%) RR 120.0 (95% CI 12.3–1009.9); P < 0.001]. A short and soft cervix also significantly increased the risk of sPTD < 37 by four-fold [6/15 (40%) vs. 15/150 (10%) RR 4.0 (95% CI 1.8–8.8); P = 0.005] and the risk of sPTD < 34, 5.7-fold [4/15 (26.7%) vs. 7/150 (4.7%) RR 5.7 (95% CI 1.9–17.3); P = 0.002], compared to a cervix that was only soft, and also marginally increased the risk of sPTD < 37 compared to a cervix that was only short [6/15 (40%) vs. 0/13; RR 11.4 (95% CI 0.7–184.3); P = 0.08] but the increase in the risk of sPTD < 34 did not reach statistical significance [4/15 (26.7%) vs. 0/13; P = 0.1].

Conversely, of the 31 sPTD < 37 deliveries, eight occurred in women who had never delivered before; 7/8 had prior miscarriages only and 6/7 had a soft cervix.

Of the 12 sPTD < 34 deliveries, 11 were associated with a soft cervix (n = 10), a prior PTD (n = 1), or both (n = 2). All women who delivered prior to 34 weeks had either a soft cervix or a prior PTD. All 12 women had been pregnant before, but four had had only prior miscarriages.

Parity and prior obstetrical history

The risk (incidence) of sPTD < 37 weeks was significantly associated with past obstetric history (χ2 = 11.5, df = 5; P = 0.04) but the risk sPTD < 34 weeks was not (χ2 = 6.98, df = 5; P = 0.2).

There was a significant association between the risk of sPTD < 37 and parity (χ2 = 12.6, df = 6; P = 0.0498) but not between sPTD < 34 and parity. The association was attributable to the significantly higher risk of sPTD < 37 among previously pregnant than first-time pregnant women. Previously pregnant women had a 7.5 times higher risk of sPTD < 37 than first-time pregnant women; however, the incidence of sPTD < 37 among this cohort of first-time pregnant women was only 0.8% (1/125), and the proportion of women who had a short cervix was only 1.6 (2/125). Because both of these frequencies were outliers, first-time pregnant women were not considered further and the analysis of the factors that affect sPTD < 37 and sPTD < 34 was confined to previously pregnant women.

Delivery prior to 37 and 34 weeks of gestation

The risk of sPTD < 37 weeks among previously pregnant women was not affected by a previous miscarriage, irrespective of whether the woman also had a previous term delivery or not. A history of a prior PTD increased the risk of sPTD < 37 by two-fold [10/116 (8.6%) vs. 21/512 (4.1%) RR 2.1 (95% CI 1.0–4.3); P = 0.05]. There was no difference in the prevalence of history of previous preterm delivery between sPTD < 34 weeks and term deliveries [3/12 (25%) vs. 106/473 (22.4%); P = 1.0].

Cervical length and cervical softness

Delivery prior to 37 weeks of gestation

Among previously pregnant women, a soft cervix alone significantly increased the risk of sPTD < 37 compared to women who did not have a soft cervix [14/142 (9.8%) vs. 10/361 (2.8%); P ≤ 0.001], and a combination of soft and short cervix significantly increased the risk of sPTD < 37 compared to women who had neither a short nor a soft cervix [6/15 (40%) vs. 10/350 (2.9%); P < 0.001] and compared to women who had only a short cervix (6/15 vs. 0/11; P = 0.02), but a short cervix alone did not significantly increase the risk of sPTD < 37 compared to women who did not have a short cervix [0/11 vs. 24/477 (5%); P = 0.6].

Delivery prior to 34 weeks of gestation

Among previously pregnant women, a soft cervix alone significantly increased the risk of sPTD < 34 compared to women who did not have a soft cervix [7/127 (5.5%) vs. 1/361 (0.3%); P < 0.001], and the combination of a soft and a short cervix significantly increased the risk of sPTD < 34 compared to women who had neither a short nor a soft cervix [4/15 (26.7%) vs. 1/350 (0.3%); P < 0.001] but not compared to women who had only a short cervix [4/15 vs. 0/11; P = 0.1]. The diagnostic indices of soft and short cervices are presented in Table 6. A short cervix had a sensitivity of 33.3%, specificity of 96.1%, a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 8.5, and a negative LR (LR−) of 0.7 for sPTD < 34, and a sensitivity of 19.4%, specificity of 96.3%, an LR+ of 5.2, and an LR− of 0.8 for sPTD < 37. The combination of a short and a soft cervix had a sensitivity of 33.3%, specificity of 98.2%, an LR+ of 18.5, and an LR− of 0.7 for sPTD < 34, and a sensitivity of 19.4%, specificity of 98.4%, an LR+ of 12.7, and an LR− of 0.8 for sPTD < 37.

Table 6.

Prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery <34 weeks (12/628; 1.9%) and <37 weeks of gestation (31/628; 4.9%) with a short cervix and the combination of a short and a soft cervix

| Short cervix (≤ 25 mm) (n=28/628; 4.6%) |

Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Likelihood ratio (+) (95% CI) |

Likelihood ratio (−) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous preterm delivery <34 weeks of gestation (n=12) | 33.3% (4/12) |

96.1% (592/616) |

14.3% (4/28) |

98.7% (592/600) |

8.5 (3.5-20.7) |

0.7 (0.5-1) |

| Spontaneous preterm delivery <37 weeks of gestation=31 | 19.4% (6/31) |

96.3% (575/597) |

21.4% (6/28) |

95.8% (575/600) |

5.2 (2.3-11.9) |

0.8 (0.7-1) |

| Short and soft cervix (shear wave speed [m/s] <25th percentile) (n=15/628; 2.4%) |

||||||

| Spontaneous preterm delivery <34 weeks of gestation n=12 | 33.3% (4/12) |

98.2% (605/616) |

26.7% (4/15) |

98.6% (605/613) |

18.5 (6.9-49.9) |

0.7 (0.5-1.01) |

| Spontaneous preterm delivery <37 weeks of gestation n=31 | 19.4% (6/31) |

98.4% (588/597) |

40% (6/15) |

95.9% (588/613) |

12.7 (4.8-33.6) |

0.8 (0.7-0.97) |

CI, confidence intervals.

In a logistic regression analysis (Table 7) in which all patients were included, a short cervix, following adjustment for previous PTD and a soft cervix, was an independent risk factor for sPTD < 34 [OR 7.7 (95% CI 1.8–29.6)] and for sPTD < 37 [OR 4.4 (95% CI 1.4–12.0)]. A soft cervix, following adjustment for previous PTD and a short cervix, was an independent risk factor for sPTD < 34 [OR 23.0 (95% CI 4.2–428)] and for sPTD < 37 [OR 4.8 (95% CI 2.2–11.2)]. The combination of a soft and a short cervix following adjustment for previous PTD was an independent risk factor for sPTD < 34 [OR 26.8 (95% CI 6.91–104.2)] and for sPTD < 37 [OR 14.4 (95% CI 4.7–44.3)].

Table 7.

The association of a short and/or a soft cervix (odds ratios (95% confidence intervals [CI]) with spontaneous preterm delivery <34 and <37 weeks of gestation

| Spontaneous preterm delivery <34 weeks (n=12; 1.9%) |

Spontaneous preterm delivery <37 weeks (n=31; 4.9%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| All patients (n=628) | ||

| Short cervix (≤ 25 mm) unadjusted (n=28) | 12.2 (3.1-41.7) | 6.2 (2.1-16) |

| Adjusted for previous preterm delivery and soft cervix | 7.7 (1.8-29.6) | 4.4 (1.4-12) |

| Variance inflation factors | 1.02/1.01/1.01 | 1.03/1.02/1.01 |

| Soft cervix unadjusted (shear wave speed [m/s] <25th percentile; n=165) | 33.4 (6.4-613.7) | 6.6 (3.1-15) |

| Adjusted for previous preterm delivery and short cervix | 23.0 (4.2-428) | 4.8 (2.2-11.2) |

| Variance inflation factors | 1.01/1.02/1.01 | 1.02/1.03/1.01 |

| Short and soft cervix; adjusted for previous preterm delivery (n=15) | 26.8 (6.91-104.2 | 14.4 (4.7-44.3) |

| Variance inflation factors | 1.0/1.0 | 1.0/1.0 |

|

In women with normal cervical length (>25 mm; n=600) | ||

| Soft cervix unadjusted (n=150) | 22.1 (3.9-418.8) | 4.8 (2.1-11.4) |

| Adjusted for previous preterm delivery | 16.8 (2.8-320.6) | 3.7 (1.6-8.9) |

| Variance inflation factors | 1.0/1.0 | 1.01/1.01 |

When only patients with a normal cervical length were included in the regression model, a soft cervix, following adjustment for history of previous PTD, was still an independent risk factor for sPTD < 34 [OR 16.8 (95% CI 2.8–320.6)] and for sPTD < 37 [OR 3.7 (95% CI 1.6–8.9)].

Discussion

Principal findings

(1) SWS declines progressively with gestational age between 18 and 24 weeks of gestation and was significantly higher at the internal than at the external cervical os at each gestational age; (2) women with a soft cervix were 3.3 timesmore likely to have a short cervix and 1.5 times more likely to have had a prior PTD than women who did not have a soft cervix; (3) compared to a cervix that was neither short nor soft, a soft cervix alone increased the risk of sPTD < 37 by 4.5-fold and the risk of sPTD < 34 by 21-fold; (4) the combination of a short and a soft cervix increased the risk of sPTD < 37 by 18-fold and the risk of sPTD < 34 by 120-fold; and (5) a soft cervix at 18–24 weeks of gestation increases the risk of sPTD <37 and <34 weeks independently of cervical length and a history of previous PTD.

Results in the context of what is known

A short cervix [4, 68–71], a prior PTD [72–74] and maternal age [75, 76] are well-established risk factors for preterm delivery. Preterm birth is a leading cause of perinatal mortality and long-term disabilities [77, 78]. Vaginal progesterone reduces the risk of PTD in women who have a short cervix with and without previous history of PTD [14,79–82]. This study shows that a soft cervix, defined as an SWS at the internal os <25th percentile for gestational age, is a risk factor for sPTD independently of cervical length.

SWS increased linearly with cervical length, and women with a short cervix were twice as likely to have a soft cervix compared to those with a normal cervical length. Consequently, there was a significant interaction between the effects of cervical length and cervical softness on the risk of sPTD < 37 and sPTD < 34. The risk of sPTD < 37 and sPTD < 34 were both greater for women who had a combination of a short and a soft cervix compared to women who only had a soft cervix. Nevertheless, among women who had neither a short cervix nor a history of a prior PTD, a soft cervix alone significantly increased the risk of sPTD < 37 and sPTD < 34 compared to women who did not have a soft cervix. Thus, a soft cervix is an independent risk factor for sPTD < 37 and sPTD < 34 weeks regardless of the presence of a short cervix or a history of prior preterm birth.

Our findings that a soft cervix is more prevalent with advanced maternal age may explain why the risk of sPTD increases in these women [75, 76, 83]. The probability of a woman having a soft cervix is 1.4 times greater than that of a woman who is 10 years younger. Nevertheless, the interaction between a soft cervix, maternal age and sPTD is complex, and in our study, it was not associated with a parallel increment in the prevalence of sPTD.

A novel finding in our study, among women with a short cervix who were treated with vaginal progesterone, was that those who delivered preterm had a soft cervix. Indeed, the risk of sPTD < 37 was significantly higher among women who had a combination of a short and a soft cervix compared to women who had only a short cervix [6/15 (40%) vs. 0/13, P = 0.017].

A history of PTD increased the risk of sPTD even in the absence of either a short or a soft cervix. This suggests that a prior PTD might act as an independent factor apart from a short or a soft cervix, suggesting that the cause of recurrent sPTD in these patients might not be completely related to a short cervix.

The evaluation of the elastic properties of the cervix provides important information about the risk of preterm delivery [84–86]. Shear-wave elastography, more reliable than strain elastography, is less operator-dependent and provides continuous estimates of the elasticity of the cervix, such as the speed of propagation of the acoustic impulse [46, 87]. The association between cervical ripening and SWE has been reported by several authors either by analyzing the effect of prostaglandins in human cervices [61] or steroids in experimental animals [63], or by documenting cervical changes in women with clinical symptoms of preterm labor [62]. In our study, SWS in the internal cervical os predicted sPTD better than in the external cervical os, probably because the alignment and organization of the collagen network in this region provides more reliable estimations of the velocity of shear-wave propagation. Differences in the organization of the collagen network in the cervix have been reported by Reusch et al. [18], who evaluated the structure of the cervix using non-linear optical microscopy after hysterectomy; the authors showed a longitudinal alignment of the collagen fibers near the endocervical canal and a circumferential arrangement near the edge of the cervix. The authors also noted a more dense concentration of longitudinal collagen fibers in the proximal part of the cervix.

Shear-wave elastography constitutes one alternative to evaluate the characteristics of the cervix aside from cervical length. The characteristics of the cervix might vary among populations; therefore, we have suggested a percentile cut-off value (25th percentile) of the SWS distribution instead of a fixed value to define a soft cervix. This cut-off was found to be effective in the current study for identifying patients with a soft cervix who are at risk of preterm delivery, regardless of the presence of a short cervix or a history of preterm birth.

Strengths and limitations

SWS was evaluated in a large group of asymptomatic women following a specific protocol for cervical evaluation, and the frequency of sPTD was carefully registered. The limitations of this study are that the frequency of preterm birth, especially <34 weeks, was low. Because all women who had a short cervix were treated with vaginal progesterone, the study of the interaction between a short and a soft cervix in non-treated patients was not performed; however, with the current standard of treatment, such a comparison might not be feasible. Nevertheless, because SWS was measured before treatment with vaginal progesterone, treatment could not have affected the associations between a short and a soft cervix and a history of prior sPTD.

Conclusion

A soft cervix, defined as an SWS <25th percentile for gestational age at 18–24 weeks of gestation, increases the risk of sPTD <37 and <34 weeks independently of cervical length and a history of previous PTD. The combination of a short and a soft cervix is associated with a LR+, suggestive that such a finding is clinically relevant to identify patients at increased risk of sPTD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, Division of Obstetrics and Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS), and, in part, with Federal funds from NICHD/NIH/DHHS under Contract No. HHSN275201300006C. The ultrasound experience and technical support of senior Registered Diagnostic Medical Sonographers (RDMS) Catherine Ducharme and Denise Haggerty are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Andersen HF, Nugent CE, Wanty SD, Hayashi RH. Prediction of risk for preterm delivery by ultrasonographic measurement of cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:859–867. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91084-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taipale P, Hiilesmaa V. Sonographic measurement of uterine cervix at 18-22 weeks’ gestation and the risk of preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:902–907. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heath VC, Southall TR, Souka AP, Elisseou A, Nicolaides KH. Cervical length at 23 weeks of gestation: prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;12:312–317. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.12050312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassan SS, Romero R, Berry SM, Dang K, Blackwell SC, Treadwell MC, et al. Patients with an ultrasonographic cervical length < or =15 mm have nearly a 50% risk of early spontaneous preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1458–1467. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owen J, Yost N, Berghella V, Thom E, Swain M, Dildy GA, 3rd, et al. Mid-trimester endovaginal sonography in women at high risk for spontaneous preterm birth. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286:1340–1348. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.11.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero R. Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:675–686. doi: 10.1002/uog.5174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalifeh A, Berghella V. Universal cervical length screening in singleton gestations without a previous preterm birth: ten reasons why it should be implemented. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:603.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Son M, Grobman WA, Ayala NK, Miller ES. A universal mid-trimester transvaginal cervical length screening program and its associated reduced preterm birth rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:365.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Temming LA, Durst JK, Tuuli MG, Stout MJ, Dicke JM, Macones GA, Cahill AG. Universal cervical length screening: implementation and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:523.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:462–469. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, Fusey S, Baxter JK, Khandelwal M, Vijayaraghavan J, Trivedi Y, Soma-Pillay P, Sambarey P, Dayal A, Potapov V, O’Brien J, Astakhov V, Yuzko O, Kinzler W, Dattel B, Sehdev H, Mazheika L, Manchulenko D, Gervasi MT, Sullivan L, Conde-Agudelo A, Phillips JA, Creasy GW, Trial P. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:18–31. doi: 10.1002/uog.9017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero R, Nicolaides K, Conde-Agudelo A, Tabor A, O’Brien JM, Cetingoz E, Da Fonseca E, Creasy GW, Klein K, Rode L, Soma-Pillay P, Fusey S, Cam C, Alfirevic Z, Hassan SS. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:124.e1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKay LA, Holford TR, Bracken MB. Re-analysis of the PREGNANT trial confirms that vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43:596–597. doi: 10.1002/uog.13331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R. Vaginal progesterone to prevent preterm birth in pregnant women with a sonographic short cervix: clinical and public health implications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.09.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero R, Nicolaides KH, Conde-Agudelo A, O’Brien JM, Cetingoz E, Da Fonseca E, Creasy GW, Hassan SS. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤ 34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;48:308–317. doi: 10.1002/uog.15953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vintzileos AM, Visser GH. Interventions for women with mid-trimester short cervix: which ones work? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49:295–300. doi: 10.1002/uog.17357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez-Andrade E, Hassan SS, Ahn H, Korzeniewski SJ, Yeo L, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Evaluation of cervical stiffness during pregnancy using semiquantitative ultrasound elastography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:152–61. doi: 10.1002/uog.12344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reusch LM, Feltovich H, Carlson LC, Hall G, Campagnola PJ, Eliceiri KW, et al. Nonlinear optical microscopy and ultrasound imaging of human cervical structure. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:031110. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.3.031110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H, Hwang HS. Elastographic measurement of the cervix during pregnancy: current status and future challenges. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2017;60:1–7. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2017.60.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.House M, Socrate S. The cervix as a biomechanical structure. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28:745–749. doi: 10.1002/uog.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Read CP, Word RA, Ruscheinsky MA, Timmons BC, Mahendroo MS. Cervical remodeling during pregnancy and parturition: molecular characterization of the softening phase in mice. Reproduction. 2007;134:327–340. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers KM, Paskaleva AP, House M, Socrate S. Mechanical and biochemical properties of human cervical tissue. Acta Biomater. 2008;4:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers K, Socrate S, Tzeranis D, House M. Changes in the biochemical constituents and morphologic appearance of the human cervical stroma during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;144(Suppl 1):S82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akins ML, Luby-Phelps K, Bank RA, Mahendroo M. Cervical softening during pregnancy: regulated changes in collagen cross-linking and composition of matricellular proteins in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:1053–1062. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.089599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao W, Gan Y, Myers KM, Vink JY, Wapner RJ, Hendon CP. Collagen fiber orientation and dispersion in the upper cervix of non-pregnant and pregnant women. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0166709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundtoft I, Langhoff-Roos J, Sandager P, Sommer S, Uldbjerg N. Cervical collagen is reduced in non-pregnant women with a history of cervical insufficiency and a short cervix. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017 Aug;96:984–990. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ophir J, Cespedes I, Ponnekanti H, Yazdi Y, Li X. Elastography: a quantitative method for imaging the elasticity of biological tissues. Ultrason Imaging. 1991;13:111–134. doi: 10.1177/016173469101300201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cespedes I, Ophir J, Ponnekanti H, Maklad N. Elastography: elasticity imaging using ultrasound with application to muscle and breast in vivo. Ultrason Imaging. 1993;15:73–88. doi: 10.1177/016173469301500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ophir J, Alam SK, Garra B, Kallel F, Konofagou E, Krouskop T, Varghese T. Elastography: ultrasonic estimation and imaging of the elastic properties of tissues. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 1999;213:203–233. doi: 10.1243/0954411991534933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garra BS. Imaging and estimation of tissue elasticity by ultrasound. Ultrasound Q. 2007;23:255–268. doi: 10.1097/ruq.0b013e31815b7ed6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nowicki A, Dobruch-Sobczak K. Introduction to ultrasound elastography. J Ultrason. 2016;16:113–124. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2016.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarvazyan A, Hall TJ, Urban MW, Fatemi M, Aglyamov SR, Garra BS. An overview of elastography – an emerging branch of medical imaging. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2011;7:255–282. doi: 10.2174/157340511798038684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garra BS. Elastography: current status, future prospects, and making it work for you. Ultrasound Q. 2011;27:177–186. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e31822a2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bamber J, Cosgrove D, Dietrich CF, Fromageau J, Bojunga J, Calliada F, Cantisani V, Correas JM, D’Onofrio M, Drakonaki EE, Fink M, Friedrich-Rust M, Gilja OH, Havre RF, Jenssen C, Klauser AS, Ohlinger R, Saftoiu A, Schaefer F, Sporea I, Piscaglia F. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 1: Basic principles and technology. Ultraschall Med. 2013;34:169–184. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1335205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Itoh A, Ueno E, Tohno E, Kamma H, Takahashi H, Shiina T, Yamakawa M, Matsumura T. Breast disease: clinical application of US elastography for diagnosis. Radiology. 2006;239:341–350. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2391041676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas A, Warm M, Hoopmann M, Diekmann F, Fischer T. Tissue Doppler and strain imaging for evaluating tissue elasticity of breast lesions. Acad Radiol. 2007;14:522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehrmohammadi M, Fazzio RT, Whaley DH, Pruthi S, Kinnick RR, Fatemi M, Alizad A. Preliminary in vivo breast vibro-acoustography results with a quasi-2-d array transducer: a step forward. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014;40:2819–2829. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Denis M, Mehrmohammadi M, Song P, Meixner DD, Fazzio RT, Pruthi S, Whaley DH, Chen S, Fatemi M, Alizad A. Comb-push ultrasound shear elastography of breast masses: initial results show promise. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Denis M, Bayat M, Mehrmohammadi M, Gregory A, Song P, Whaley DH, Pruthi S, Chen S, Fatemi M, Alizad A. Update on breast cancer detection using comb-push ultrasound shear elastography. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2015;62:1644–1650. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2015.007043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bayat M, Denis M, Gregory A, Mehrmohammadi M, Kumar V, Meixner D, Fazzio RT, Fatemi M, Alizad A. Diagnostic features of quantitative comb-push shear elastography for breast lesion differentiation. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dudea SM, Giurgiu CR, Dumitriu D, Chiorean A, Ciurea A, Botar-Jid C, Coman I. Value of ultrasound elastography in the diagnosis and management of prostate carcinoma. Medical Ultrason. 2011;13:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bae U, Dighe M, Dubinsky T, Minoshima S, Shamdasani V, Kim Y. Ultrasound thyroid elastography using carotid artery pulsation: preliminary study. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:797–805. doi: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehrmohammadi M, Song P, Meixner DD, Fazzio RT, Chen S, Greenleaf JF, Fatemi M, Alizad A. Comb-push ultrasound shear elastography (CUSE) for evaluation of thyroid nodules: preliminary in vivo results. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34:97–106. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2014.2346498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ami O, Lamazou F, Mabille M, Levaillant JM, Deffieux X, Frydman R, Musset D. Real-time transvaginal elastosonography of uterine fibroids. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:486–488. doi: 10.1002/uog.7358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Degos F, Perez P, Roche B, Mahmoudi A, Asselineau J, Voitot H, Bedossa P. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan and comparison to liver fibrosis biomarkers in chronic viral hepatitis: a multicenter prospective study (the FIBROSTIC study) J Hepatol. 2010;53:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maurer MM, Badir S, Pensalfini M, Bajka M, Abitabile P, Zimmermann R, Mazza E. Challenging the in-vivo assessment of biomechanical properties of the uterine cervix: A critical analysis of ultrasound based quasi-static procedures. J Biomech. 2015;48:1541–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas A. Imaging of the cervix using sonoelastography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;28:356–357. doi: 10.1002/uog.3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swiatkowska-Freund M, Preis K. Elastography of the uterine cervix: implications for success of induction of labor. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:52–56. doi: 10.1002/uog.9021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Molina F, Gomez L, Florido J, Padilla M, Nicolaides K. Quantification of cervical elastography. A reproducibility study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2012;39:685–689. doi: 10.1002/uog.11067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swiatkowska-Freund M, Traczyk-Los A, Preis K, Lukaszuk M, Zielinska K. Prognostic value of elastography in predicting premature delivery. Ginekol Pol. 2014;85:204–207. doi: 10.17772/gp/1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kobbing K, Fruscalzo A, Hammer K, Mollers M, Falkenberg M, Kwiecien R, Klockenbusch W, Schmitz R. Quantitative elastography of the uterine cervix as a predictor of preterm delivery. J Perinatol. 2014;34:774–780. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hernandez-Andrade E, Romero R, Korzeniewski SJ, Ahn H, Aurioles-Garibay A, Garcia M, Schwartz AG, Yeo L, Chaiworapongsa T, Hassan SS. Cervical strain determined by ultrasound elastography and its association with spontaneous preterm delivery. J Perinat Med. 2014;42:159–169. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2013-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fruscalzo A, Londero AP, Frohlich C, Meyer-Wittkopf M, Schmitz R. Quantitative elastography of the cervix for predicting labor induction success. Ultraschall Med. 2015;36:65–73. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1355572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lockwood CJ. Risk factors for preterm birth and new approaches to its early diagnosis. J Perinat Med. 2015;43:499–501. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2015-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Londero AP, Schmitz R, Bertozzi S, Driul L, Fruscalzo A. Diagnostic accuracy of cervical elastography in predicting labor induction success: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perinat Med. 2016;44:167–178. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2015-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sarvazyan AP, Rudenko OV, Swanson SD, Fowlkes JB, Emelianov SY. Shear wave elasticity imaging: a new ultrasonic technology of medical diagnostics. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1998;24:1419–1435. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(98)00110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shiina T, Nightingale KR, Palmeri ML, Hall TJ, Bamber JC, Barr RG, Castera L, Choi BI, Chou YH, Cosgrove D, Dietrich CF, Ding H, Amy D, Farrokh A, Ferraioli G, Filice C, Friedrich-Rust M, Nakashima K, Schafer F, Sporea I, Suzuki S, Wilson S, Kudo M. WFUMB guidelines and recommendations for clinical use of ultrasound elastography: Part 1: basic principles and terminology. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:1126–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruno C, Minniti S, Bucci A, Pozzi Mucelli R. ARFI: from basic principles to clinical applications in diffuse chronic disease-a review. Insights Imaging. 2016;7:735–746. doi: 10.1007/s13244-016-0514-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carlson LC, Feltovich H, Palmeri ML, Dahl JJ, Munoz Del Rio A, Hall TJ. Estimation of shear wave speed in the human uterine cervix. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Apr;43:452–458. doi: 10.1002/uog.12555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peralta L, Molina FS, Melchor J, Gomez LF, Masso P, Florido J, et al. Transient elastography to assess the cervical ripening during pregnancy: a preliminary study. Ultraschall Med. 2017;38:395–402. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1553325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carlson LC, Romero ST, Palmeri ML, Munoz Del Rio A, Esplin SM, Rotemberg VM, Hall TJ, Feltovich H. Changes in shear wave speed pre- and post-induction of labor: a feasibility study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46:93–98. doi: 10.1002/uog.14663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muller M, Ait-Belkacem D, Hessabi M, Gennisson JL, Grange G, Goffinet F, Lecarpentier E, Cabrol D, Tanter M, Tsatsaris V. Assessment of the cervix in pregnant women using shear wave elastography: a feasibility study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:2789–2797. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peralta L, Mourier E, Richard C, Charpigny G, Larcher T, Ait-Belkacem D, et al. In vivo evaluation of cervical stiffness evolution during induced ripening using shear wave elastography, histology and 2 photon excitation microscopy: insight from an animal model. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0133377. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hernandez-Andrade E, Garcia M, Ahn H, Korzeniewski SJ, Saker H, Yeo L, Chaiworapongsa T, Hassan SS, Romero R. Strain at the internal cervical os assessed with quasi-static elastography is associated with the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery at ≤34 weeks of gestation. J Perinat Med. 2015;43:657–666. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Burger M, Weber-Rossler T, Willmann M. Measurement of the pregnant cervix by transvaginal sonography: an interobserver study and new standards to improve the interobserver variability. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;9:188–193. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.09030188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Romero R, Yeo L, Miranda J, Hassan SS, Conde-Agudelo A, Chaiworapongsa T. A blueprint for the prevention of preterm birth: vaginal progesterone in women with a short cervix. J Perinat Med. 2013;41:27–44. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2012-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hernandez-Andrade E, Aurioles-Garibay A, Garcia M, Korzeniewski SJ, Schwartz AG, Ahn H, Martinez-Varea A, Yeo L, Chaiworapongsa T, Hassan SS, Romero R. Effect of depth on shear-wave elastography estimated in the internal and external cervical os during pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2014;42:549–557. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ, Mercer BM, Moawad A, Das A, et al. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:567–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Erez O, Kusanovic JP, Mazaki-Tovi S, Gotsch F, et al. Clinical significance of early (< 20 weeks) vs. late (20–24 weeks) detection of sonographic short cervix in asymptomatic women in the mid-trimester. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36:471–481. doi: 10.1002/uog.7673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vaisbuch E, Hassan SS, Mazaki-Tovi S, Nhan-Chang CL, Kusanovic JP, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Patients with an asymptomatic short cervix (<or =15 mm) have a high rate of subclinical intraamniotic inflammation: implications for patient counseling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:433.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharvit M, Weiss R, Ganor Paz Y, Tzadikevitch Geffen K, Danielli Miller N, Biron-Shental T. Vaginal examination vs. cervical length – which is superior in predicting preterm birth? J Perinat Med. 2017;45:977–983. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Adams MM, Elam-Evans LD, Wilson HG, Gilbertz DA. Rates of and factors associated with recurrence of preterm delivery. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283:1591–1596. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ananth CV, Getahun D, Peltier MR, Salihu HM, Vintzileos AM. Recurrence of spontaneous versus medically indicated preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Esplin MS, O’Brien E, Fraser A, Kerber RA, Clark E, Simonsen SE, et al. Estimating recurrence of spontaneous preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:516–523. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318184181a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laopaiboon M, Lumbiganon P, Intarut N, Mori R, Ganchimeg T, Vogel JP, et al. Advanced maternal age and pregnancy outcomes: a multicountry assessment. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;121:49–56. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ogawa K, Urayama KY, Tanigaki S, Sago H, Sato S, Saito S, et al. Association between very advanced maternal age and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a cross sectional Japanese study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:349. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1540-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee BH, Seri I. Prematurity. J Perinat Med. 2016;44:601–603. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sen C. Preterm labor and preterm birth. J Perinat Med. 2017;45:911–913. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2017-0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Romero R, Yeo L, Chaemsaithong P, Chaiworapongsa T, Hassan SS. Progesterone to prevent spontaneous preterm birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;19:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berghella V. What’s new in preterm birth prediction and prevention? J Perinat Med. 2017;45:1–4. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ahn KH, Bae NY, Hong SC, Lee JS, Lee EH, Jee HJ, et al. The safety of progestogen in the prevention of preterm birth: metaanalysis of neonatal mortality. J Perinat Med. 2017;45:11–20. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2015-0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, Da Fonseca E, O’Brien JM, Cetingoz E, Creasy GW, et al. Vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm birth and adverse perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations with a short cervix: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:161–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baer RJ, Yang J, Berghella V, Chambers CD, Coker TR, Kuppermann M, et al. Risk of preterm birth by maternal age at first and second pregnancy and race/ethnicity. J Perinat Med. 2018;46:539–546. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2017-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.von Schoning D, Fischer T, von Tucher E, Slowinski T, Weichert A, Henrich W, Thomas A. Cervical sonoelastography for improving prediction of preterm birth compared with cervical length measurement and fetal fibronectin test. J Perinat Med. 2015;43:531–536. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2014-0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wozniak S, Czuczwar P, Szkodziak P, Wrona W, Paszkowski T. Elastography for predicting preterm delivery in patients with short cervical length at 18-22 weeks of gestation: a prospective observational study. Ginekol Pol. 2015;86:442–447. doi: 10.17772/gp/2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oturina V, Hammer K, Mollers M, Braun J, Falkenberg MK, Murcia KO, Mollmann U, Eveslage M, Fruscalzo A, Klockenbusch W, Schmitz R. Assessment of cervical elastography strain pattern and its association with preterm birth. J Perinat Med. 2017;45:925–932. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2016-0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fruscalzo A, Mazza E, Feltovich H, Schmitz R. Cervical elastography during pregnancy: a critical review of current approaches with a focus on controversies and limitations. J Med Ultrason (2001) 2016;43:493–504. doi: 10.1007/s10396-016-0723-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]