Abstract

Objective

To calculate pooled risk estimates for combinations of cytology result, human papillomavirus (HPV) 16/18 genotype, and colposcopy impression to provide a basis for risk-stratified colposcopy and biopsy practice.

Data source

A PubMed search was conducted on June 1, 2016, and a ClinicalTrials.gov search was conducted on June 9, 2018, using key words such as “uterine cervical neoplasms,” “cervical cancer,” “mass screening,” “early detection of cancer” and “colposcopy.”

Methods of Study Selection

Eligible studies must have included colposcopic impression and either cytology results or HPV16/18 partial genotype results as well as a histologic biopsy diagnosis from adult women. Manuscripts were reviewed for the following: cytology, HPV status, and colposcopy impression, as well as age, number of women, and number of CIN2, CIN3, and cancer cases. Strata were defined by the various combinations of cytology, genotype, and colposcopic impression.

Tabulation, Integration, and Results

Of 340 abstracts identified, 9 were eligible for inclusion. Data were also obtained from three unpublished studies, two of which have since been published. We calculated the risk of CIN2+ and CIN3+ based on cytology, colposcopy, and HPV16/18 test results. We found similar risk patterns across studies in the lowest risk groups such that risk estimates were similar despite different referral populations and study designs. Women with a normal colposcopy impression (no acetowhitening), <HSIL cytology, and HPV16/18 negative were at low risk of prevalent precancer. Women with at least two of the following: HSIL cytology, HPV16 or HPV18 positive, high-grade colposcopic impression were at highest risk of prevalent precancer.

Conclusions

Our results support a risk-based approach to colposcopy and biopsy with modifications of practice at the lowest and highest risk levels.

Introduction

Effective cervical cancer screening programs have greatly reduced the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States 1. A key component is identifying and appropriately managing women with abnormal screening results following cytology or HPV tests. Frequently, this involves referral to colposcopy where the cervix is visualized under magnification and biopsies are collected for histologic diagnosis, enabling identification of high-risk women in need of treatment and lower risk women in need of follow-up.

Although all women referred for colposcopy have had an abnormal screening result, their underlying risk of cervical cancer varies greatly depending on the type of test(s) and corresponding result(s) leading to their referral. Risk also varies according to colposcopic findings. Combined, these factors can be used to estimate a woman’s risk of precancer, and in turn guide colposcopy practice and appropriate next steps, including whether to treat immediately or take biopsies, and the appropriate number of biopsies to take.

Despite its key role in cervical cancer screening, colposcopy is subjective and imprecise 2. In light of this, the American Society for Colposcopy & Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) established several working groups to review current colposcopy practices in the US and develop consensus recommendations to standardize colposcopy practices and ensure a complete exam3–7. This entailed establishing risk estimates to guide management recommendations at the time of colposcopy. To do so, a literature review and meta-analysis was conducted evaluating risk strata based on combinations of cytology, HPV 16/18 genotyping, and colposcopy impression that may impact colposcopy and biopsy practice.

Sources

An extensive literature review was conducted and data were pooled from published and unpublished studies for a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the risk of precancer in various strata based on cytology, HPV testing, and colposcopy impression. The following search terms were used in PubMed on June 1, 2016: (((“uterine cervical neoplasms”[MeSH Terms] OR (“uterine”[All Fields] AND “cervical”[All Fields] AND “neoplasms”[All Fields]) OR “uterine cervical neoplasms”[All Fields] OR (“cervical”[All Fields] AND “cancer”[All Fields]) OR “cervical cancer”[All Fields]) AND (“diagnosis”[Subheading] OR “diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “screening”[All Fields] OR “mass screening”[MeSH Terms] OR (“mass”[All Fields] AND “screening”[All Fields]) OR “mass screening”[All Fields] OR “screening”[All Fields] OR “early detection of cancer”[MeSH Terms] OR (“early”[All Fields] AND “detection”[All Fields] AND “cancer”[All Fields]) OR “early detection of cancer”[All Fields])) AND “female”[MeSH Terms] AND “adult”[MeSH Terms]) AND ((“Colposcopy/methods”8 OR “Colposcopy/statistics and numerical data”8 OR “Colposcopy/utilization”8) AND “female”[MeSH Terms] AND “adult”[MeSH Terms]) AND (“female”[MeSH Terms] AND “adult”[MeSH Terms]). The following search terms were used in ClinicalTrials.gov on June 9, 2018: ((“uterine” AND “cervical” AND “neoplasms”) OR (“cervical” AND “cancer”) )AND (“diagnosis” OR “screening” OR (“early” AND “detection” AND “cancer”)) AND “female” AND “adult” AND “colposcopy”.

Study Selection

The PubMed search was performed on June 1, 2016 and yielded 340 manuscripts. An additional search of ClinicalTrials.gov on June 9, 2018 did not yield any additional results. The search results were divided among eight co-authors and abstracts were reviewed and screened for relevance. One hundred ninety-six references were divided among eight co-authors and read in their entirety to determine eligibility and the availability of relevant data for analysis. Twenty-five percent of articles had a second review to ensure consistency. In order to calculate absolute risk estimates in the various risk strata, an abstraction sheet was developed to capture information on the following: Cytology (<HSIL vs HSIL+), HPV status with partial genotyping (HPV16 or HPV18 positive vs HPV16 and HPV18 negative), and colposcopy impression (normal, metaplasia/acetowhitening not suspicious for intraepithelial lesion, low-grade, or high-grade), as well as age, number of women in different risk strata, and number of CIN2, CIN3, and cancer. A normal colposcopic impression was defined as no acetowhitening or other abnormalities. Metaplasia/acetowhitening not suspicious for intraepithelial lesion (hereafter referred to as acetowhitening) is denoted as a separate category, since normal squamous metaplasia can have a mild acetowhite appearance, which is considered by many colposcopists to be benign. Study identification of CIN2+ and CIN3+ endpoints included both targeted and random biopsies as well as excisional procedures (LEEP/conization). Biopsy procedures varied by study—no specified number of biopsies was required.

References were excluded if they did not contain colposcopic impression along with either cytology or HPV16/18 partial genotyping. Nine references met the criteria for inclusion and risk information was abstracted from the full manuscript 9–17. Bias was assessed in these studies using an adapted QUADAS tool 18. All studies were found to have a low to uncertain risk of bias, so all were included in the analysis. In addition, unpublished primary data were obtained from three studies (ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study 19, The Biopsy Study 20, and the BD Onclarity trial) and included in the meta-analysis. Two of these studies have since been published 21,22. Details about included studies can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary data from included studies by strata

| Strata | Manuscript first author | Year | Age Group | N | CIN2+ | CIN3+ | Proportion CIN2+ | Proportion CIN3+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-grade colpo and HSIL+ | Sadan | 2007 | NS | 79 | 56 | 0.7089 | ||

| Aue-aungkul | 2011 | 25+ | 110 | 102 | 0.9273 | |||

| Bosgraaf | 2013 | 17+ | 1543 | 1473 | 0.9546 | |||

| Errington | 2006 | NS | 448 | 372 | 0.8304 | |||

| Szurkus | 2003 | NS | 34 | 24 | 0.7059 | |||

| Vanseviciute | 2003 | 23+ | 33 | 30 | 0.9091 | |||

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 155 | 122 | 92 | 0.7871 | 0.5935 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 17 | 13 | 10 | 0.7647 | 0.5882 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 108 | 81 | 28 | 0.7500 | 0.2593 | |

| High-grade colpo and <HSIL | Aue-aungkul | 2011 | 25+ | 40 | 23 | 0.5750 | ||

| Bosgraaf | 2013 | 17+ | 256 | 181 | 0.7070 | |||

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 206 | 75 | 39 | 0.3641 | 0.1893 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 150 | 24 | 10 | 0.1600 | 0.0667 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 99 | 48 | 14 | 0.4848 | 0.1414 | |

| Low-grade colpo and HSIL+ | Errington | 2006 | NS | 117 | 59 | 0.5043 | ||

| Szurkus | 2003 | NS | 58 | 34 | 0.5862 | |||

| Aue-aungkul | 2011 | 25+ | 23 | 17 | 0.7391 | |||

| Bosgraaf | 2013 | 17+ | 238 | 170 | 0.7143 | |||

| Hedge | 2011 | 20+ | 11 | 8 | 6 | 0.7273 | 0.5455 | |

| Vanseviciute | 2003 | 23+ | 15 | 4 | 0.2667 | |||

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 229 | 121 | 75 | 0.5284 | 0.3275 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 67 | 41 | 19 | 0.6119 | 0.2836 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 80 | 42 | 10 | 0.5250 | 0.1250 | |

| Low-grade colpo and <HSIL | Bosgraaf | 2013 | 17+ | 297 | 79 | 0.2660 | ||

| Aue-aungkul | 2011 | 25+ | 19 | 6 | 0.3158 | |||

| Hedge | 2011 | 20+ | 25 | 1 | 1 | 0.0400 | 0.0400 | |

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 1259 | 173 | 65 | 0.1374 | 0.0516 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 1830 | 200 | 80 | 0.1093 | 0.0437 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 248 | 74 | 12 | 0.2984 | 0.0484 | |

| Acetowhite/Metaplasia colpo and HSIL+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 15 | 5 | 1 | 0.3333 | 0.0667 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 15 | 3 | 1 | 0.2000 | 0.0667 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 17 | 5 | 2 | 0.2941 | 0.1176 | |

| Acetowhite/Metaplasia colpo and <HSIL | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 182 | 24 | 8 | 0.1319 | 0.0440 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 943 | 45 | 21 | 0.0477 | 0.0223 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 56 | 4 | 0 | 0.0714 | 0.0000 | |

| Normal colpo and <HSIL | Huh | 2014 | 2106 | 42 | 17 | 0.0199 | 0.0081 | |

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 503 | 5 | 3 | 0.0099 | 0.0060 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 1766 | 37 | 17 | 0.0210 | 0.0096 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 42 | 3 | 0 | 0.0714 | 0.0000 | |

| Normal colpo and HSIL+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 21 | 1 | 1 | 0.0476 | 0.0476 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 34 | 8 | 4 | 0.2353 | 0.1176 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| High-grade colpo and HPV16/18+ | Zaal | 2012 | 18 | 17 | 14 | 0.9444 | 0.7778 | |

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 182 | 133 | 103 | 0.7308 | 0.5659 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 31 | 19 | 13 | 0.6129 | 0.4194 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 83 | 65 | 29 | 0.7831 | 0.3494 | |

| High-grade colpo and HPV16/18− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 182 | 63 | 28 | 0.3462 | 0.1538 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 136 | 18 | 7 | 0.1324 | 0.0515 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 131 | 69 | 17 | 0.5267 | 0.1298 | |

| Low-grade colpo and HPV16/18+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 463 | 180 | 107 | 0.3888 | 0.2311 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 287 | 98 | 58 | 0.3415 | 0.2021 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 85 | 51 | 16 | 0.6000 | 0.1882 | |

| Low-grade colpo and HPV16/18− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 1040 | 119 | 36 | 0.1144 | 0.0346 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 1610 | 153 | 41 | 0.0950 | 0.0255 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 250 | 69 | 7 | 0.2760 | 0.0280 | |

| Acetowhite/metaplasia colpo and 16/18+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 48 | 11 | 5 | 0.2292 | 0.1042 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 137 | 15 | 11 | 0.1095 | 0.0803 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 15 | 3 | 1 | 0.2000 | 0.0667 | |

| Acetowhite/metaplasia colpo and 16/18− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 150 | 18 | 4 | 0.1200 | 0.0267 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 821 | 33 | 11 | 0.0402 | 0.0134 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 62 | 6 | 1 | 0.0968 | 0.0161 | |

| Normal colpo and HPV16/18+ | Huh | 2014 | 221 | 19 | 9 | 0.0860 | 0.0407 | |

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 110 | 2 | 2 | 0.0182 | 0.0182 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 203 | 17 | 9 | 0.0837 | 0.0443 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Normal colpo and HPV16/18− | Huh | 2014 | 1885 | 23 | 8 | 0.0122 | 0.0042 | |

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 423 | 4 | 2 | 0.0095 | 0.0047 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 1597 | 28 | 12 | 0.0175 | 0.0075 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 45 | 3 | 0 | 0.0667 | 0.0000 | |

| High-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 105 | 90 | 75 | 0.8571 | 0.7143 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 9 | 8 | 6 | 0.8889 | 0.6667 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 57 | 45 | 19 | 0.7895 | 0.3333 | |

| High-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 49 | 31 | 17 | 0.6327 | 0.3469 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 8 | 5 | 4 | 0.6250 | 0.5000 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 50 | 35 | 9 | 0.7000 | 0.1800 | |

| High-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 75 | 43 | 28 | 0.5733 | 0.3733 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 22 | 11 | 7 | 0.5000 | 0.3182 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 24 | 18 | 9 | 0.2400 | 0.3750 | |

| High-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 131 | 32 | 11 | 0.2443 | 0.0840 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 128 | 13 | 3 | 0.1016 | 0.0234 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 75 | 30 | 5 | 0.4000 | 0.0667 | |

| Low-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 116 | 78 | 57 | 0.6724 | 0.4914 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 22 | 17 | 10 | 0.7727 | 0.4545 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 27 | 19 | 9 | 0.7037 | 0.3333 | |

| Low-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 112 | 42 | 18 | 0.3750 | 0.1607 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 45 | 24 | 9 | 0.5333 | 0.2000 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 53 | 23 | 1 | 0.4340 | 0.0189 | |

| Low-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 340 | 98 | 48 | 0.2882 | 0.1412 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 265 | 81 | 48 | 0.3057 | 0.1811 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 58 | 32 | 7 | 0.5517 | 0.1207 | |

| Low-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 915 | 75 | 17 | 0.0820 | 0.0186 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 1565 | 119 | 32 | 0.0760 | 0.0204 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 188 | 42 | 5 | 0.2234 | 0.0266 | |

| Acetowhite/metaplasia colpo and HSIL+ and HPV+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0.3333 | 0.1111 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.1667 | 0.1667 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0.3333 | 0.1667 | |

| Acetowhite/metaplasia colpo and HSIL+ and HPV− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0.3333 | 0.0000 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0.2222 | 0.0000 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 11 | 3 | 1 | 0.2727 | 0.0909 | |

| Acetowhite/metaplasia colpo and <HSIL and HPV+ | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 39 | 8 | 4 | 0.2051 | 0.1026 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 131 | 14 | 10 | 0.1069 | 0.0763 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0.1250 | 0.0000 | |

| Acetowhite/metaplasia colpo and <HSIL and HPV− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 141 | 16 | 4 | 0.1135 | 0.0284 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 812 | 31 | 11 | 0.0382 | 0.0135 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 48 | 3 | 0 | 0.0625 | 0.0000 | |

| Normal colpo and HSIL+ and HPV+ | ALTS | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | ||

| BD | 9 | 5 | 3 | 0.5556 | 0.3333 | |||

| Biopsy | -- | -- | -- | |||||

| Normal colpo and HSIL+ and HPV− | ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 25 | 3 | 1 | 0.1200 | 0.0400 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Normal colpo and <HSIL and HPV+ | Huh | 2014 | 221 | 19 | 9 | 0.0860 | 0.0407 | |

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 100 | 1 | 1 | 0.0100 | 0.0100 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 194 | 12 | 5 | 0.0619 | 0.0258 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Normal colpo and <HSIL and HPV− | Huh | 2014 | 660 | 15 | 6 | 0.0227 | 0.0091 | |

| ALTS | 2017 | 18+ | 402 | 4 | 2 | 0.0100 | 0.0050 | |

| BD | 2017 | 25+ | 1572 | 25 | 11 | 0.0159 | 0.0070 | |

| Biopsy | 2017 | 18+ | 38 | 3 | 0 | 0.0789 | 0.0000 |

The proportion of women in each of the risk strata were calculated using the three studies with complete data across all 32 risk strata (BD, Biopsy, ALTS). Pooled risks of CIN2 and CIN3 using all 12 studies were calculated using available data for each strata using metaprop_one 23 in Stata 14.2 (College Station, TX, USA). Metaprop was designed as an addition to the metan command specifically for binomial data. The Freeman-Tukey double arc-sine transformation was used to stabilize the variance and account for studies with zero events to ensure confidence intervals remained within plausible bounds (0–1) 23. I2 was used as a measure of heterogeneity, and random effects models were used to account for the variability in the studies. This paper will present the meta-analysis results for CIN2+ risk estimates as more data were available for this outcome; however, the meta-analysis results for CIN3+ risk estimates are included in Appendix 1–3, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

Results

We considered risk estimates based on all combinations of the results a woman could have at the time of colposcopy that included colposcopic impression and could affect management: 8 strata of colposcopy impression and cytology results; 8 strata of colposcopy impression and HPV16/18 status; 16 strata of colposcopy impression, cytology result, and HPV16/18 status. The specifics of these risk strata are detailed in Box 1. A minimum of three studies per strata were required for the meta-analysis, and all but one stratum (normal colposcopy, HSIL+ and HPV16/18+) met this criterion.

Box 1. List of Risk Strata.

| Colposcopy & Cytology |

|---|

| High-grade colpo and HSIL+ |

| High-grade colpo and <HSIL |

| Low-grade colpo and <HSIL |

| Low-grade colpo and HSIL+ |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and HSIL+ |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and <HSIL |

| Normal colpo and <HSIL |

| Normal colpo and HSIL+ |

| Colposcopy & HPV16/18 |

|---|

| High-grade colpo and HPV16/18+ |

| High-grade colpo and HPV16/18− |

| Low-grade colpo and HPV16/18+ |

| Low-grade colpo and HPV16/18− |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and 16/18+ |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and 16/18− |

| Normal colpo and HPV16/18+ |

| Normal colpo and HPV16/18− |

| Colposcopy & Cytology & HPV16/18+ |

|---|

| High-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18+ |

| High-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18− |

| High-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18+ |

| High-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18− |

| Low-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18+ |

| Low-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18− |

| Low-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18+ |

| Low-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18− |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and HSIL+ and 16/18+ |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and HSIL+ and 16/18− |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and <HSIL and 16/18+ |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and <HSIL and 16/18− |

| Normal colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18+ |

| Normal colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18− |

| Normal colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18+ |

| Normal colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18− |

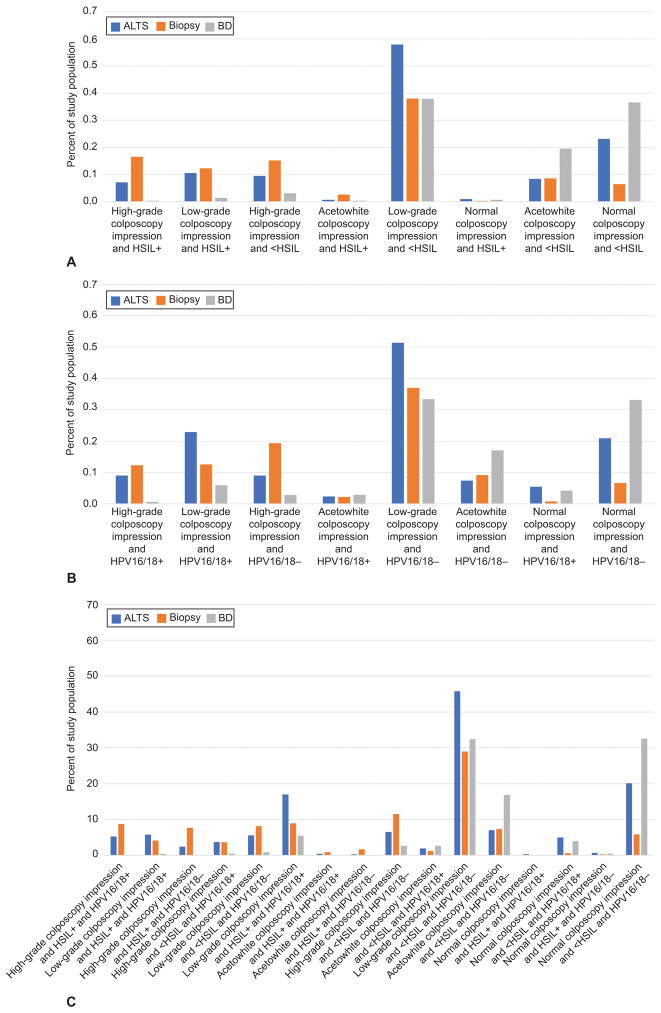

Complete data for all possible combinations of risk strata were available from three of the twelve included studies 19,20,24), and were used to estimate the proportion of women expected to fall within each stratum. These distributions are summarized in Figure 1. The pattern was more similar between ALTS and the Biopsy study (cytology-referral populations) than between either of those studies and the BD Study (HPV-referral population), although the three studies were largely in agreement on the largest and smallest strata. Based on colposcopy and cytology results, between 40–60% of the women seen in colposcopy clinic could be expected to have a low-grade colposcopy impression and <HSIL cytology, while 1% or less will have high-grade cytology and a normal colposcopy impression. Similarly, when colposcopic impression and HPV16/18 status are known, 30–50% could be expected to have low-grade colposcopy and HPV16/18 negative results, while 6% or less would have normal colposcopies, but be HPV16/18 positive. For clinics using cytology and HPV16/18 genotyping along with colposcopy impression, the largest proportion of women (35–65%) would be expected to have normal or low-grade colposcopic impression, <HSIL cytology and HPV16/18 negative. In contrast, <2% of women with HSIL+ had a normal or acetowhite colposcopy. Exact numeric estimates for the three studies can be found in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Population distribution of risk strata combinations. Colposcopy and cytology (A), colposcopy and HPV16/18 (B), and colposcopy, cytology, and HPV16/18. HPV, human papillomavirus; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; BD, Becton Dickinson; ALTS, ASCUS/LSIL Triage Study.

Table 2.

Population distribution of risk strata combinations

| Colposcopy & Cytology

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALTS | Biopsy | BD | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| High-grade colpo and HSIL+ | 155 | 7.1% | 108 | 16.6% | 17 | 0.4% |

| Low-grade colpo and HSIL+ | 229 | 10.5% | 80 | 12.3% | 67 | 1.4% |

| High-grade colpo and <HSIL | 206 | 9.5% | 99 | 15.2% | 150 | 3.1% |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and HSIL+ | 15 | 0.7% | 17 | 2.6% | 15 | 0.3% |

| Low-grade colpo and <HSIL | 1259 | 58.0% | 248 | 38.0% | 1830 | 38.0% |

| Normal colpo and HSIL+ | 21 | 1.0% | 2 | 0.3% | 34 | 0.7% |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and <HSIL | 182 | 8.4% | 56 | 8.6% | 943 | 19.6% |

| Normal colpo and <HSIL | 503 | 23.2% | 42 | 6.4% | 1766 | 36.6% |

|

| ||||||

| Total Population | 2570 | 652 | 4822 | |||

| Colposcopy & HPV16/18

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALTS | Biopsy | BD | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| High-grade colpo and HPV16/18+ | 182 | 9.0% | 83 | 12.3% | 31 | 0.6% |

| Low-grade colpo and HPV16/18+ | 463 | 22.9% | 85 | 12.6% | 287 | 6.0% |

| High-grade colpo and HPV16/18− | 182 | 9.0% | 131 | 19.4% | 136 | 2.8% |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and 16/18+ | 48 | 2.4% | 15 | 2.2% | 137 | 2.8% |

| Low-grade colpo and HPV16/18− | 1040 | 51.4% | 250 | 37.0% | 1610 | 33.4% |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and 16/18− | 150 | 7.4% | 62 | 9.2% | 821 | 17.0% |

| Normal colpo and HPV16/18+ | 110 | 5.4% | 5 | 0.7% | 203 | 4.2% |

| Normal colpo and HPV16/18− | 423 | 20.9% | 45 | 6.7% | 1597 | 33.1% |

|

| ||||||

| Total Population | 2598 | 676 | 4822 | |||

| Colposcopy & Cytology & HPV16/18+

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALTS | Biopsy | BD | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| High-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18+ | 105 | 5.3% | 57 | 8.8% | 9 | 0.2% |

| Low-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18+ | 116 | 5.8% | 27 | 4.2% | 22 | 0.5% |

| High-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18− | 49 | 2.5% | 50 | 7.7% | 8 | 0.2% |

| High-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18+ | 75 | 3.8% | 24 | 3.7% | 22 | 0.5% |

| Low-grade colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18− | 112 | 5.6% | 53 | 8.2% | 45 | 0.9% |

| Low-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18+ | 340 | 17.0% | 58 | 8.9% | 265 | 5.5% |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and HSIL+ and 16/18+ | 9 | 0.5% | 6 | 0.9% | 6 | 0.1% |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and HSIL+ and 16/18− | 6 | 0.3% | 11 | 1.7% | 9 | 0.2% |

| High-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18− | 131 | 6.6% | 75 | 11.6% | 128 | 2.7% |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and <HSIL and 16/18+ | 39 | 2.0% | 8 | 1.2% | 131 | 2.7% |

| Low-grade colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18− | 915 | 45.8% | 188 | 29.0% | 1565 | 32.5% |

| Metaplasia/Acetowhite colpo and <HSIL and 16/18− | 141 | 7.1% | 48 | 7.4% | 812 | 16.8% |

| Normal colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18+ | 7 | 0.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 0.2% |

| Normal colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18+ | 100 | 5.0% | 4 | 0.6% | 194 | 4.0% |

| Normal colpo and HSIL+ and HPV16/18− | 14 | 0.7% | 2 | 0.3% | 25 | 0.5% |

| Normal colpo and <HSIL and HPV16/18− | 402 | 20.1% | 38 | 5.9% | 1572 | 32.6% |

|

| ||||||

| Total Population | 2561 | 649 | 4822 | |||

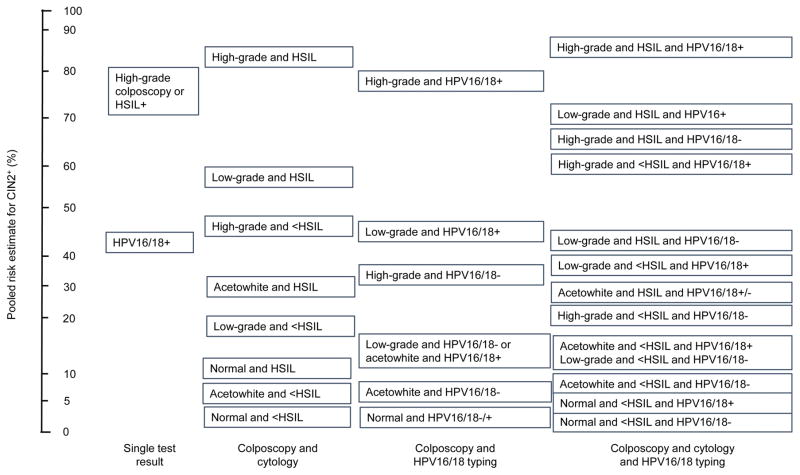

CIN2+ pooled risk estimates were first calculated for a positive result on each of the three tests and then for all possible combinations of colposcopy impression, cytology, and HPV16/18 genotyping results (Figure 2). High-grade colposcopy impression and high-grade cytology results yielded similar risk estimates (0.73 (95% CI: 0.53–0.89) and 0.75 (95% CI: 0.64–0.85), respectively). The CIN2+ risk associated with a positive HPV16/18 result alone was 0.43 (95% CI: 0.24–0.63).

Figure 2.

Pooled risk estimates by test result. Rank ordered pooled risk estimate of CIN2+ by strata of test results. HPV, human papillomavirus. HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.

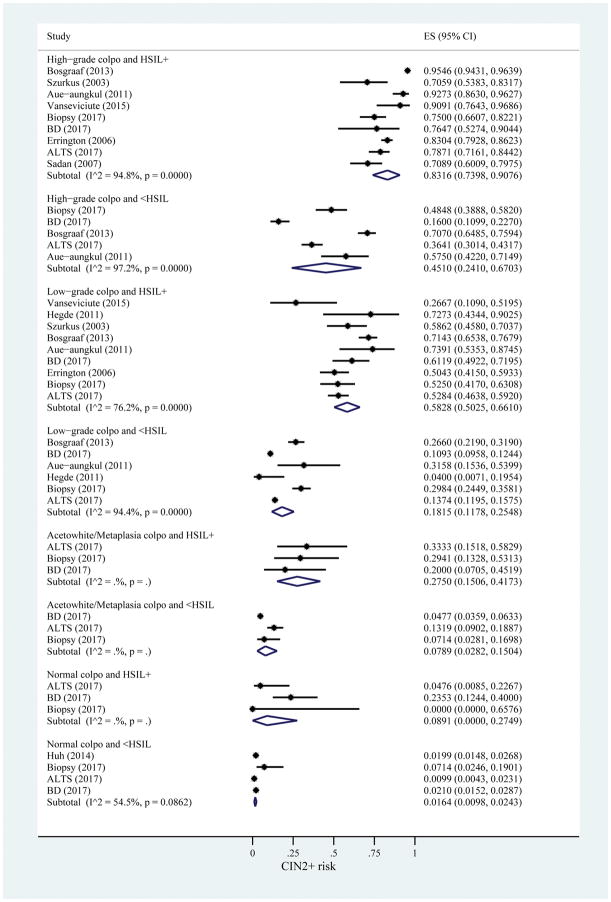

All twelve included data sources providing data for at least one of the risk strata using colposcopy impression and cytology result as risk markers for CIN2+. In this set of data, there was a range of risk estimates from 0.83 (95% CI: 0.74–0.91) at the high end for high-grade colposcopy with HSIL+ to 0.02 (95% CI: 0.01–0.02) at the low end for normal colposcopy and <HSIL (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Risk estimates for CIN2+ based on colposcopy impression and cytology result. I2 only calculated when number of studies is greater than 3. ES, estimated risk of CIN2+; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; BD, Becton Dickinson; ALTS, ASCUS/LSIL Triage Study.

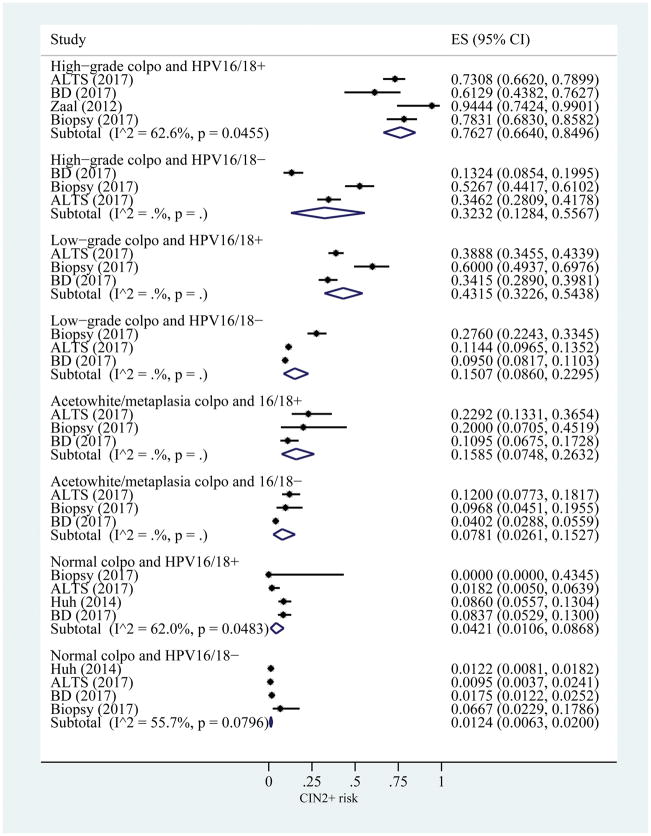

The CIN2+ risk estimates using colposcopy and HPV16/18 status, ranged from 0.76 (95% CI: 0.66–0.85) for high-grade colposcopy impression and HPV16/18+ to 0.01 (95% CI: 0.01–0.02) for normal colposcopy impression and HPV16/18− (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Risk estimates for CIN2+ based on colposcopy impression and HPV16/18 status. I2 only calculated when number of studies is greater than 3. ES, estimated risk of CIN2+; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HPV, human papillomavirus; ALTS, ASCUS/LSIL Triage Study; BD, Becton Dickinson.

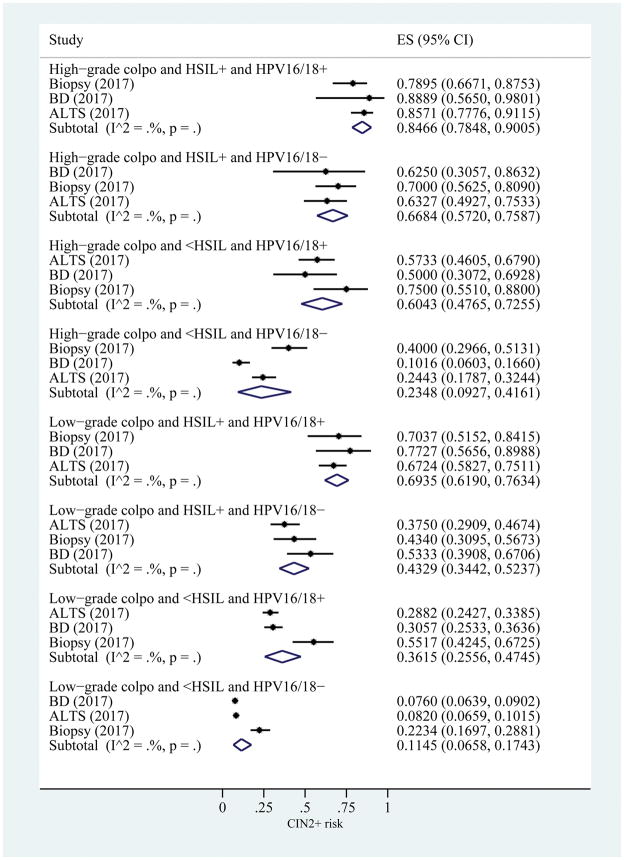

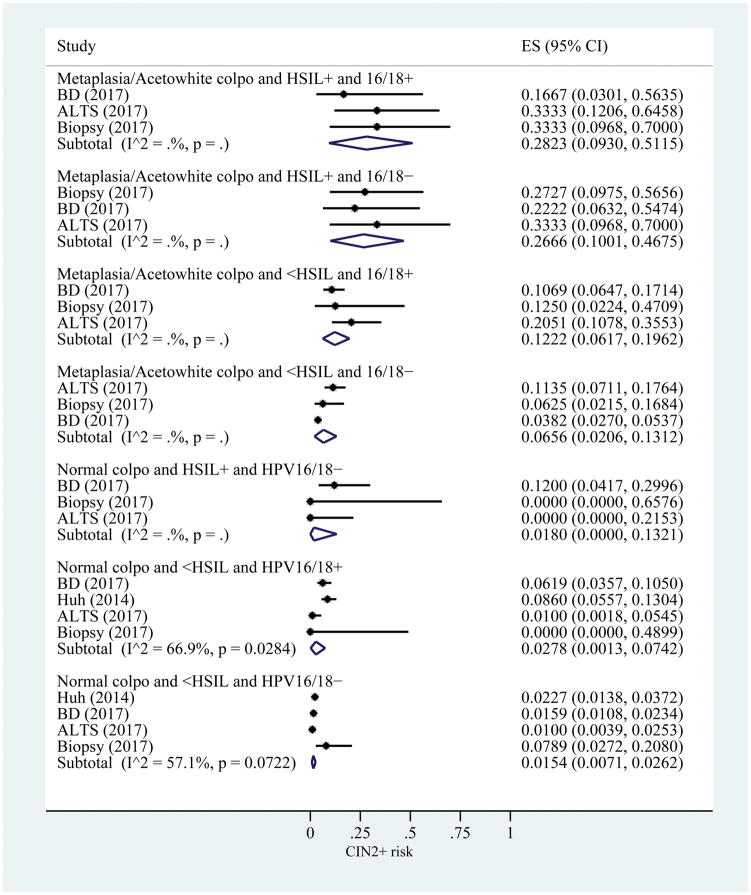

For the CIN2+ risk estimates including all 3 results, the range was 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78–0.90) for those with a high-grade colposcopy impression, HSIL+, and HPV16/18 positive to 0.015 (95% CI: 0.007–0.026) for those with a normal colposcopy impression, <HSIL cytology, and HPV16/18 negative (Figure 5). Four strata had pooled risked estimates above 60%: high-grade colposcopy impression, HSIL+, and HPV16/18 positive; high-grade colposcopy impression, HSIL+, and HPV16/18 negative; high-grade colposcopy impression, <HSIL, and HPV16/18 positive, and low-grade colposcopy impression, HSIL+, and HPV16/18 positive.

Figure 5.

Risk estimates for CIN2+ based on colposcopy impression, cytology result, and HPV16/18 status. I2 only calculated when number of studies is greater than 3. B is a continuation of A. ES, estimated risk of CIN2+; CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HSIL, high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions; HPV, human papillomavirus; BD, Becton Dickinson; ALTS, ASCUS/LSIL Triage Study.

Pooled risk estimates for CIN3+ can be found in Appendixes 1–3 (http://links.lww.com/xxx), and demonstrate a reduction in heterogeneity of risk estimates for this higher-grade outcome compared to CIN2+, both across and within risk strata. Pooled risk estimates for CIN3+ exhibited similar patterns to CIN2+, but lower absolute risks were seen for all strata. CIN3+ risk estimates for colposcopy/cytology risk strata can be found in Appendix 1 (http://links.lww.com/xxx), for colposcopy/HPV16/18 risk strata in Appendix 2 (http://links.lww.com/xxx), and for colposcopy, cytology and HPV16/18 in Appendix 3 (http://links.lww.com/xxx).

Comment

Colposcopy, biopsy and subsequent management following abnormal Pap smears have played a critical role in our ability to prevent cervical cancer by identifying and treating precancers. Yet, as screening shifts to Pap/HPV cotesting or primary HPV testing and the vaccinated population ages into screening, the volume and underlying risk of women referred to colposcopy will change dramatically. To prevent overburdening the health system and over-treating women at low-risk, a risk-based approach to triage and management is needed that accounts for varying levels of risk among a colposcopy referral population. We calculated pooled risk estimates for combinations of cytology, HPV, and colposcopy impression of all currently available data to support recommendations for risk-based colposcopy and biopsy practice.

Importantly, we found a similarity in risk patterns across studies in the lowest risk groups such that risk estimates were similar within a stratum despite different referral populations and study designs. Greater heterogeneity was seen at the highest risk groups, though all estimates in those categories would still be considered high-risk. With fine risk stratification, differences between populations can be addressed to a certain point. Our results also demonstrated the rarity of extreme combinations such as normal or acetowhite colposcopies with HPV16/18+ or HSIL+, regardless of the referral strategy, though these data come from trained colposcopists in trial settings, and may not be generalizable to the national population of providers performing colposcopy.

We focused primarily on results for CIN2+ due to the limited number of studies presenting data for CIN3+. However even with the small sample size, the pooled risk estimates for CIN3+ were much less heterogeneous than the CIN2+ results, likely reflecting the known variability and lack of reproducibility of CIN2 diagnoses 25,26, and suggesting the need for separation of CIN2 from CIN3+ when presenting clinical outcomes of cervical cancer screening, triage, and management. The reduced homogeneity and consistency of risk estimates for these true precancer outcomes supports the use of a risk-based approach to cervical cancer screening and management.

The ASCCP recently issued new colposcopy standards and risk-based management guidelines for the lowest and highest risk groups of women based on available test results (cytology, HPV, and colposcopy impression). Our results support the recommendation against non-targeted (random) biopsies for women with a normal colposcopy impression (no acetowhitening), <HSIL cytology, and HPV16/18 negative, due to their low risk of prevalent precancer, estimated to be under 2% for CIN2+ and under 0.5% for CIN3+. This modification in protocols can eliminate unnecessary biopsies for anywhere between 6 and 33% of women undergoing colposcopy depending on the measures used for initial referral to colposcopy.

The new ASCCP recommendations also suggest immediate excisional treatment for the highest risk women (at least two of the following: HSIL cytology, HPV16 or HPV18 positive, high-grade colposcopic impression) as an alternative to colposcopic biopsy7, as is currently allowed for HSIL cytology alone27. Again, our calculations support this, showing risks of prevalent CIN2+ ranging from 60% to 85% and CIN3+ risks of 29% to 57% for most women with at least 2 high-grade results. We estimate this new guideline could allow immediate treatment for 2–25% of women (depending on the measures used for referral), reducing cost and emotional distress for the patient as well as the need for an additional visit and potential loss to follow-up.

A limitation of this analysis worth noting is the variability in how colposcopy impression is defined and identified by individual providers. This may lead to some added heterogeneity or misclassification in colposcopy impression across studies. Widespread implementation of the newly established colposcopy standards can aid in reducing the variability of colposcopy. These guidelines create a set of standardized terminology and standardized procedures for conducting and documenting colposcopy and also developed quality improvement recommendations. A second limitation is that as HPV-vaccinated women mature into screening, we expect risk estimates for colposcopic impression and cytology to decline, so the estimates generated here may require updating in the future. Differences in referral populations may influence risk estimates, particularly in an HPV screened population, where women may be referred for colposcopy for two consecutive HPV positive NILM Pap smears, who wouldn t be found in a cytology referral population. These women likely will have smaller lesions, which are harder to detect by colposcopy.

While colposcopy procedures will change for women at the highest and lowest risks of cervical precancer and cancer, the majority of women referred to colposcopy (60–80%) will present with intermediate risk levels (at least one risk factor: high-grade colposcopy, HSIL cytology, or HPV16/18 positive), and these women should continue to be managed according to standard protocol including at least two and up to four biopsies of acetowhite lesions to determine appropriate next steps7,27. It is among this group of intermediate-risk results where identification of additional biomarkers for cervical cancer will be most beneficial, allowing increased precision for risk estimation and tailored management recommendations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The National Cancer Institute has received cervical cytology and HPV testing results for independent NCI-directed studies at reduced or no cost from Roche and Becton Dickinson.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Andrews, Dr. Cooper, and Dr. Parvu and are full-time employees of BD (Becton Dickinson & Company). Dr. Massad has received personal fees from malpractice firms for consultation on cases alleging missed cervical cancer, honoraria, and expenses for development of guidelines (2012 ACS cervical screening, 2013 ASCCP management) from ASCCP. He served on FDA advisory panel that recommended approval of primary HPV screening by Roche assay. He has not had financial relationships with companies involved in manufacture/marketing of HPV assays or HPV vaccine or diagnostic equipment or therapies. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented in part at the ASCCP Annual Meeting, April 19–21, 2018, Las Vegas, Nevada.

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

References

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2014 National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD: posted to the SEER website April 2017 [updated Based on November 2016 SEER data submission. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massad LS, Jeronimo J, Schiffman M, et al. Interobserver agreement in the assessment of components of colposcopic grading. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1279–84. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816baed1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan MJ, Werner C, Darragh TM, et al. ASCCP Colposcopy Standards: Role of colposcopy, benefits, potential harms, and terminology for colposcopic practice. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayeaux EJ, Novetsky AP, Chelmow D, et al. ASCCP Colposcopy Standards: Colposcopy Quality Improvement Recommendations for the United States. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waxman AG, Conageski C, Silver MI, et al. ASCCP Colposcopy Standards: How Do We Perform Colposcopy? Implications for Establishing Standards Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2017;21(4):235–41. doi: 10.1097/lgt.0000000000000336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wentzensen N, Massad LS, Mayeaux EJJ, et al. Evidence-Based Consensus Recommendations for Colposcopy Practice for Cervical Cancer Prevention in the United States. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2017;21(4):216–22. doi: 10.1097/lgt.0000000000000322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Silver MI, et al. ASCCP Colposcopy Standards: Risk-based colposcopy practice. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017 doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankaranarayanan R, Basu P, Wesley RS, et al. Accuracy of visual screening for cervical neoplasia: Results from an IARC multicentre study in India and Africa. International Journal of Cancer. 2004;110(6):907–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadan O, Yarden H, Schejter E, et al. Treatment of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: A “see and treat” versus a three-step approach. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2007;131(1):73–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aue-aungkul A, Punyawatanasin S, AN, et al. “See and Treat” Approach is Appropriate in Women with Highgrade Lesions on either Cervical Cytology or Colposcopy. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(7):1723–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosgraaf RP, Mast P-P, Struik-van der Zanden PHTH, et al. Overtreatment in a See-and-Treat Approach to Cervical Intraepithelial Lesions. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;121(6):1209–16. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318293ab22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Errington CA, Roberts M, Tindle P, et al. Colposcopic management of high-grade referral smears: a retrospective audit supporting ‘see and treat’? Cytopathology. 2006;17(6):339–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2006.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szurkus DC, Harrison TA. Loop excision for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion on cytology: Correlation with colposcopic and histologic findings. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188(5):1180–82. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vansevičiūtė R, Venius J, Žukovskaja O, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic-acid-based fluorescence spectroscopy and conventional colposcopy for in vivo detection of cervical pre-malignancy. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15:35. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0191-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hegde D, Shetty H, Shetty P, et al. Diagnostic value of acetic acid comparing with conventional Pap smear in the detection of colposcopic biopsy-proved CIN. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics. 2011;7(4):454–58. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.92019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaal A, Louwers JA, Berkhof J, et al. Agreement between colposcopic impression and histological diagnosis among human papillomavirus type 16-positive women: a clinical trial using dynamic spectral imaging colposcopy. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2012;119(5):537–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huh WK, Sideri M, Stoler M, et al. Relevance of Random Biopsy at the Transformation Zone When Colposcopy Is Negative. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2014;124(4):670–78. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000000458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, et al. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2003;3(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiffman M, Adrianza ME. ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study. Design, methods and characteristics of trial participants Acta Cytol. 2000;44(5):726–42. doi: 10.1159/000328554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(1):83–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.9948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoler MH, Wright TC, Parvu V, et al. The Onclarity Human Papillomavirus Trial: Design, methods, and baseline results. Gynecologic Oncology. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Wentzensen N, Walker J, Smith K, et al. A prospective study of risk-based colposcopy demonstrates improved detection of cervical precancers. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2018;218(6):604e1–04.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoler M, Wright T, Parvu V, et al. The BD Onclarity Human Papillomavirus Study: design, methods, and baseline results. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.04.007. manuscript in preparation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stoler MH, Schiffman M for the Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance–Low-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion Triage Study G. Interobserver reproducibility of cervical cytologic and histologic interpretations: Realistic estimates from the ascuslsil triage study. JAMA. 2001;285(11):1500–05. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.11.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carreon JD, Sherman ME, Guillén D, et al. CIN2 Is a Much Less Reproducible and Less Valid Diagnosis than CIN3: Results from a Histological Review of Population-Based Cervical Samples. International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 2007;26(4):441–46. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0b013e31805152ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al. 2012 Updated Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;121(4):829–46. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.