Abstract

Clinical trial outcomes for Alzheimer’s disease are typically analyzed by using the mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) or similar models that compare an efficacy scale change from baseline between treatment arms with or without participants’ disease stage as a covariate. The MMRM focuses on a single-point fixed follow-up duration regardless of the exposure for each participant. In contrast to these typical models, we have developed a novel semiparametric cognitive disease progression model (DPM) for autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease based on the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) observational study. This model includes 3 novel features, in which the DPM (1) aligns and compares participants by disease stage, (2) uses a proportional treatment effect similar to the concept of the Cox proportional hazard ratio, and (3) incorporates extended follow-up data from participants with different follow-up durations using all data until last participant visit. We present the DPM model developed by using the DIAN observational study data and demonstrate through simulation that the cognitive DPM used in hypothetical intervention clinical trials produces substantial gains in power compared with the MMRM.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, disease progression model, mixed effects model for repeated measures, proportional treatment effect

1 | INTRODUCTION

The Alzheimer’s disease (AD) field has progressively moved to studying potential disease-modifying therapies in earlier stages of disease, including in asymptomatic stages before dementia onset. The failure to develop effective disease-modifying treatments in the later dementia stages of disease1,2 has supported the notion that prevention is likely to be more effective. However, AD prevention trials require long periods of follow-up because of the slowly progressive nature of cognitive decline over many years, creating a major challenge in the implementation of prevention trials. For example, participant attrition and long enrollment durations combined with long treatment periods make implementation of large complex prevention trials impractical and less efficient. Several strategies are being pursued to mitigate these challenges, including the development of surrogate biomarkers,3 more sensitive measures of cognitive disease progression,4 and platform trials to test several targets in parallel.5 In addition, the advancement of statistical methods provides an opportunity to greatly increase the power, speed, and efficiency of AD prevention trials.

Several strategies may be incorporated to increase power, including increasing overall sample sizes,6,7 adjusting the sample size based on results from interim analysis,8 using a targeted trial that enrolls only a very specific population,9 or using enrollment enrichment strategies to reduce heterogeneity of trial participants.10 Although these trial designs may improve the ability to detect effective treatments, they have drawbacks including increased time, expense, and limited generalizability. Because trial outcomes are typically determined with the mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) using time since baseline as a categorical variable or even cross-sectional models that focus on comparing the absolute cognitive change from baseline to a fixed post baseline time point,6,7,11,12 typical clinical trials collect clinical assessments for a fixed duration for each participant. And the participants who were enrolled early and had completed the fixed follow-up duration were no longer active, while the late enrollees were still fulfilling the follow-up. Thus, the early enrollees with potentially the longest and most valuable exposure if continuously followed do not contribute to a stronger analysis. This lost opportunity is even more significant in prevention trials with extended enrollment times. Additionally, participants typically enter trials at different stages of disease; thus, statistical models that ignore disease stage and look at change from trial baseline introduce additional heterogeneity due to variability of disease stage. Overall, these shortcomings have resulted in trial designs that require large sample sizes and long exposure to achieve acceptable statistical power.2,6,7 We demonstrate that a disease progression model (DPM) built from the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) observational cohort avoids each of these shortcomings to greatly increase power.

Autosomal-dominant AD (ADAD) is a rare genetic disorder caused by a mutation in 1 of 3 genes: amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1), or presenilin 2 (PSEN2). Mutation carriers are destined to develop dementia of the Alzheimer’s type, generally at an early age, typically with the age of onset between 30 and 50 years.13 Age of onset for asymptomatic mutation carriers can be estimated from other carriers of the same mutation. The estimated years from symptom onset (EYO) for an individual is their current age minus their estimated age of onset.14 Within the DIAN observational study, we have shown that EYO is a reliable predictor of disease stage.14,15 Additionally, it also provides a remarkably consistent rate of cognitive disease progression across participants. We have developed a cognitive disease progression model (DPM) based on the DIAN observational study that models the rate of cognitive progression as a function of EYO. The consistency of the rate of decline as a function of EYO is striking. We demonstrate how this cognitive DPM is used in a hypothetical phase III interventional trial and compare the power of the cognitive DPM with the more conventional MMRM model typically used in AD clinical trials.

2 | MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 | DIAN observational study

The DIAN observational study is an international, multisite, longitudinal study of individuals from families with an established history of ADAD. Participants must have confirmation of a causal ADAD mutation in their family, with a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation. From the disease modeling aspects of this paper, we analyze only confirmed mutation carriers. The details of participants’ demographics and the clinical, cognitive, imaging, and biochemical measures have been reported in previous publications.14 The data used in the DPM development include DIAN quality-controlled data from July 2008 to January 2015 consisting of 225 mutation carriers.

2.2 | Estimated years from symptom onset (EYO)

Each participant in the study has an estimated age of onset. The assignment of an age of onset for each participant is based on the mean age of onset for that person’s specific matching mutation established through systematic review and meta-analysis.15 Each clinical assessment occurs at a time differential from the participant’s estimated age of onset—we refer to the timing as the EYO. Specifically, the EYO is calculated as the age of the participant at the time of the clinical assessment minus this participant’s estimated age of onset. For example, at an assessment, if a participant’s age is 45.3 years, and the estimated age of onset for this participant is 50.2, then EYO for that assessment is −4.9, meaning that this participant is about 4.9 years to his/her symptom onset.

2.3 | Cognitive composite

The cognitive composite used in these analyses combines measures of episodic memory, executive functioning, processing speed, and mental status and was chosen to sensitively measure the cognitive decline, which occurs before the first symptom onset in preclinical AD. Three separate approaches using a mathematically optimized approach,16 basic principles of neuropsychology,17,18 and evaluating prior demonstrated domains in sporadic AD were compared and found to converge on the 4 domains included in the cognitive composite for this study. This composite is similar to other composites. 19 Episodic memory is assessed with the DIAN Word List test delayed recall and the delayed recall score from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical Memory IIA subtest.20 Executive functioning and processing speed is assessed with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised Digit-Symbol Substitution test, and mental status with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). This cognitive composite was developed by normalizing each individual test to a z-score before averaging. All components except the MMSE are normalized using the mean and standard deviation (SD) of each component score from mutation carriers well before symptom onset (EYO ≤ −15). However, the MMSE has a ceiling effect, the SD among those with EYO ≤ −15 is small, and using this SD will overweight MMSE. A simple smoothing spline model for the rate of decline of MMSE was fit, and the estimated SD from the model is used for the normalization. The details for the normalization are provided in the Supporting Information.

Next, the 4 z-scores are equally weighted to construct a single composite. The construction of the cognitive composite creates a single score with mean zero and SD near 1 for participants in a healthy state (EYO ≤ −15).

2.4 | The cognitive DPM based on the DIAN observational study

Let Yij be the jth cognitive composite measured at EYOij for participant i, i = 1, …, k. Let ni be the number of observations for participant i. The underlying rationale of the cognitive DPM is to represent a participant’s composite score at any given EYO as a function of this participant’s score in a healthy stage (defined as EYO ≤ −15 in this study) plus a decline from the relatively healthy stage to this particular EYO. The cognitive composite is modeled as a function of EYOij by using a mixed-effects model,

The random effect parameter γi is the individual cognitive composite at the relatively healthy stage defined as (EYO ≤ −15) in this study. The function f(x) represents the mean decline from the relatively healthy stage to a given EYO (the semiparametric model presented below). The random effect δi represents a participant-level adjustment to incorporate the uncertainty in the estimate for the covariate age of onset.

Function f(x) is modeled as a monotonically decreasing spline with knots at each integer value for EYO between (inclusive) −15 and +15, represented by α−15, α−14, …, α15. The modeling puts no restriction on the shape of the decline curve—it does not enforce linearity, but only a decline in cognitive mean as the participant ages. The decline is defined for all continuous EYOs by using linear interpolation between the values of α

| (1) |

where [x] is the floor function and it represents the largest integer less than x. The parameters for this model are the values of f at each knot point αx. The errors, εij, are assumed to be independent and identically distributed with a normal distributions N(0, σ2). The prior distributions for the 2 random effects across participants are modeled as: γi~N(0, 1), δi~N (0, 2); the variance, σ2, is assumed to be a weak (nearly non-informative) prior inverse-gamma distribution: σ2~IG (0.01, 0.01), and the αs are assumed to be proportional to a weak normal distribution restricted to decreasing values:

For identifiability, we assume that the mean cognitive score at EYO −15 (considered as healthy) is 0; thus, participants with EYO ≤ −15 or less are represented as Yij = γi + εij. This preserves the interpretation of the random effect γi to represent the mean cognitive score in a healthy state of the individual. This monotonicity assumption in α plays 2 very important roles. The first is that it forces the estimates of the mean cognitive composite to decline over time—accounting for the scientifically expected result as part of the model. The second is that this restriction creates inherent smoothing as well, creating a smooth estimate of the mean decline over time.

To calculate the posterior distribution, an MCMC algorithm is used with a single chain after a burn-in of 10 000 observations and a chain length of 100 000. The algorithm uses adaptively updated Metropolis-Hastings steps for improved convergence and mixing.21,22 See the Supporting Information for further details.

2.5 | Estimated natural decline of ADAD population using DIAN observational study

We apply the mixed effects cognitive DPM to the DIAN observational data. The posterior mean and SD of the natural decline at each EYO point—the α in Equation (1)—are presented in Table 1. In Table S2, the posterior mean and SD of the natural decline is provided without the monotonicity assumption. Each decline parameter, α, represents the mean decline in the cognitive composite from the healthy state. The model estimated decline from an EYO of −15 to an EYO of 0 (onset) is −1.06, meaning that the mean decline to the point of estimated symptom onset is approximately a 1 point z-score decline in the cognitive endpoint. In the 4 years following onset, there is an estimated additional 1.09 decline, meaning that the rate of decline is estimated to increase 3 to 4 times after onset compared with the 15 years before onset. The posterior mean of the model standard error of the cognitive test around the true mean, σ, is 0.333 with a SD of 0.019.

TABLE 1.

The posterior mean (SD) of the mean cognitive decline for each EYO estimated by the cognitive disease progression model using Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network observational study

| EYO | Posterior Mean (SD) of αEYO | EYO | Posterior Mean (SD) of αEYO |

|---|---|---|---|

| −15 | 0 (0) | 1 | −1.20 (0.18) |

| −14 | −0.07 (0.06) | 2 | −1.40 (0.29) |

| −13 | −0.14 (0.08) | 3 | −1.70 (0.41) |

| −12 | −0.21 (0.09) | 4 | −2.15 (0.44) |

| −11 | −0.27 (0.09) | 5 | −2.66 (0.38) |

| −10 | −0.33 (0.10) | 6 | −2.93 (0.34) |

| −9 | −0.39 (0.10) | 7 | −3.11 (0.38) |

| −8 | −0.46 (0.11) | 8 | −3.37 (0.37) |

| −7 | −0.53 (0.11) | 9 | −3.71 (0.24) |

| −6 | −0.61 (0.12) | 10 | −3.86 (0.24) |

| −5 | −0.68 (0.12) | 11 | −4.07 (0.27) |

| −4 | −0.76 (0.12) | 12 | −4.29 (0.37)a |

| −3 | −0.83 (0.13) | 13 | −6.10 (0.94)a |

| −2 | −0.90 (0.13) | 14 | −7.77 (1.51)a |

| −1 | −0.98 (0.14) | 15 | −9.22 (1.73)a |

| 0 | −1.06 (0.14) |

The minimum of this composite score is −4.11, which is achieved around estimated years from symptom onset (EYO) 11 or when all the components have scores of 0. These z-scores are less than the minimum and are model estimated decline that had the monotonic decline continued beyond EYO 11. However, autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease patients rarely if any survive past EYO 10.

2.6 | Modeling therapeutic treatment effect

With the progression of cognitive decline estimated as a function of EYO, we are interested in modeling a potential treatment effect on the rate of cognition decline in the ADAD population. We extend the above-described mixed effects model of cognitive decline across natural history participants to incorporate a treatment effect under an experimental treatment with an assumption of a proportional treatment effect to the rate of natural cognitive decline. In particular, if a treatment is provided to subject i at time Ti, measured on the time scale of EYO, then the model for the cognitive endpoint incorporates the effect of the treatment from the point of intervention forward. The multiplicative effect to the future rate of progression after intervention is modeled as eθ, with log-progression rate θ. The cognitive composite Yij with corresponding timing of the observation as EYOij, is modeled as

The decline function g is a combination of the natural decline f and the effect of the intervention θ:

The random effects γi and δi, the variance σ2, and the mean decline at each knot (α) are modeled in the same way as in Equation (1). The prior distribution for the decline parameters is varied from the original model to have an SD of 1.5 between yearly deviations. The choice was based on calibrating the model to have good type I error properties while still being relatively uninformative. The priors of α’s are set to be

The effect of a treatment is captured by the parameter θ. The value of eθ is the proportional effect of the treatment and is referred as the cognitive progression ratio (CPR). If the CPR is equal to 1, then the rate of decline on the treatment is identical to the control (natural history or placebo) after the treatment intervention. A value of the CPR larger than 1 would indicate an increased rate of decline for the treatment compared with the control. If the CPR is less than 1, then the rate of decline is slower for the treatment than for the control. The value of the CPR is interpreted as the ratio of the rate of decline under the treatment to the control; thus, this quantity is directly interpretable as the size of the treatment effect and its clinical relevance. The CPR can be thought of much like a hazard ratio in a time to event analysis.23 For example, if the CPR is 0.70, then the rate of decline on the treatment is slowed by 30% compared with the control.

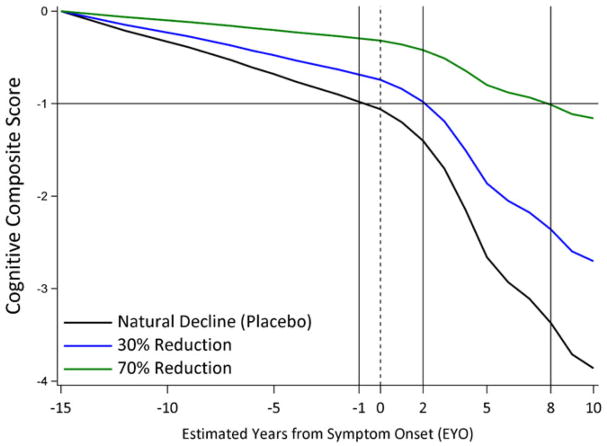

We explore the ramifications of different treatment effects by showing how a modeled treatment effect slows the cognitive decline. Figure 1 shows the estimated natural decline and the decline if a treatment is started at EYO −15 with a 30% slowing (blue) or 70% slowing (green). A mutation carrier is expected to naturally decline to a z-score of −1 approximately at EYO −1. A 30% treatment effect would lead to a delay of 3 years (from EYO −1 to EYO 2) to reach the same −1 z-score, whereas a 70% treatment effect would lead to a delay of 9 years.

FIGURE 1.

The decline trajectories for natural history and for 30% and 70% treatment effects [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

2.7 | Simulation of ADAD clinical trials

To demonstrate the behavior of the cognitive DPM, we simulated virtual ADAD clinical trials by using the DPM as the primary analysis. We selected the virtual patient simulation parameters to closely mimic the original DIAN-TU trial design. We simulated trials with 3:1 treatment to placebo randomization ratio of 80 patients. We include 2 interim analyses for efficacy. Overall, we make the following assumptions for our simulated trials:

Sample size: 80 (60:20)

Duration: 4-year follow up after the last enrolled participant for any group. If cognitive measures beyond 4-year follow-up are available for participants enrolled earlier in the trial, the data will be incorporated into the cognitive endpoint model to estimate the treatment effect.

Accrual rate: a mean of 5 per month simulated from a Poisson distribution

Frequency of cognitive assessments: every 6 months

Dropout rate: 5% annually, simulated independent of cognitive value, meaning missing completely at random

-

Simulation of an individual participant

An EYO at enrollment is simulated as a uniform value over the integers from −15 to +10 (inclusive).

Expected natural cognitive progression: All new placebo participants behave like the cognitive model (with assumed monotonically decreasing cognitive mean values) estimates from the DIAN observational data, with respective variability of new measurements. In particular, posterior mean estimates given in Table 1 that were estimated using all DIAN observational participants are used to simulate the cognitive measure (including the SD of 0.333). The postbaseline scores are simulated assuming a treatment CPR value (1 for placebo, and different values of CPR for the experimental treatment).

A simulation of CDR global based on the baseline cognitive composite is conducted to determine if the additional entry criterion of CDR global ≤1 is met. If the CDR global criterion is not met, a substitute participant is simulated until the participant meets the CDR global condition.

Interim analysis: 2 interim analyses are conducted: when the last participant in the treatment cohort reaches 2 years and 3 years of follow-up. At each interim, the treatment will be stopped for efficacy if it demonstrations a statistically superior slowing of cognitive decline. If efficacy is not demonstrated at any interim analyses, then the experimental treatment will continue to the next interim analysis or the final analysis. The rules defined for efficacy success are as follows: a treatment will be stopped early for efficacy if the posterior probability that the treatment slows the rate of cognitive decline is greater than or equal to 0.9952 (see the Supporting Information for the calculation of this threshold to control type I error).

Primary analysis: The primary analysis is performed when the last participant enrolled to the trial has been followed for 4 years. The null hypothesis of the primary analysis is H0: CPR = 1 against the alternative hypothesis: HA: CPR < 1. The treatment will be declared successful, and the null hypothesis rejected in favor of the alternative, and a slowing of the rate of cognitive decline concluded if the posterior probability of a CPR < 1 is greater than or equal to 0.9952. The threshold for final success has been determined to control the one-sided type I error at 0.025 or less taking into account the interim analyses.

Assuming hypothetical values of CPR ranging from 0% to 80%, we simulated 5000 trials for each reduction, and 50 000 draws from each MCMC algorithm to calculate posterior probabilities. Power is estimated as the proportion of the 5000 trials that meet a primary analysis of superiority. Using the same simulated data, analyses based on MMRM were also conducted. The MMRM analysis model included participant-level random effects, a fixed effect for the cognitive score at baseline for placebo and treated participants, fixed effects for time-varying rates of decline for placebo participants (where time is included as years since baseline and is used as categorical), and fixed effects for time-varying treatment effects for treatment participants. The treatment effect at year 4 is tested by contrasting the group difference. The power using MMRM is estimated as the proportion of the 5000 trials with P-value less than .05 for a 2-sided test. Simulations of the DPM were conducted by using Fortran and the MMRM analysis conducted using R.

2.8 | Trial simulation results

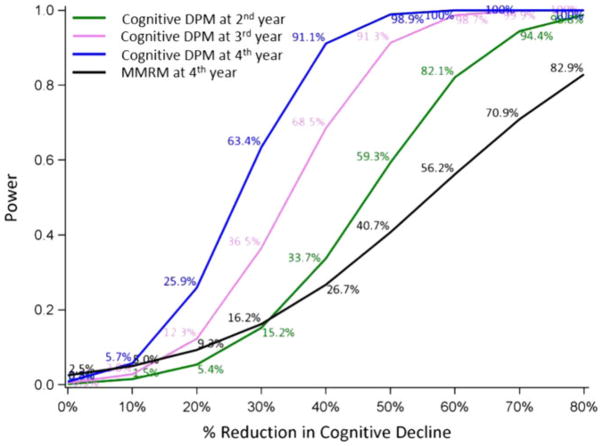

Figure 2 presents the power using the cognitive DPM as a function of the assumed treatment effect with analyses at the second, third, and fourth years. Additionally, the power of the MMRM at the fourth year for the exact same assumptions is shown. The cognitive DPM yields a substantial increase in power compared with the traditional MMRM (Figure 2). For an assumed 40% reduction in the cognitive decline, the cognitive DPM provides 91.1% power whereas the MMRM only yield 26.7% power at the fourth year analysis. Importantly, we show that even for therapies with greater than 50% effect on slowing disease progression, using an MMRM approach still yields less than 50% power to detect this effect at the fourth year. Even the second and third year analyses using cognitive DPM yield more power than MMRM when the reduction in cognitive decline is more than 30%.

FIGURE 2.

Power comparison between the cognitive disease progression model (DPM) and mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) for a sample size of 60:20 (treatment: placebo). The gains in power using the cognitive DPM are striking compared with the commonly used MMRM model [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The 3 main reasons for this substantial increase are as follows:

Positioning a participant in the model based on their EYO rather than change from baseline

Allowing the extended follow-up to contribute to the primary analysis in a very strong way

The assumption of a common proportional effect across time for the treatment arm rather than fitting the effect for a single visit

To understand the role that the first of these plays consider a participant coming in at an EYO of −14. The expected decline is very different from a participant coming in at an EYO of +1. The MMRM analysis characterizes the observations as time from baseline, while the cognitive DPM treats them as the progression relative to their stage of disease (EYO). The estimated SD for a single cognitive test using the cognitive DPM is 0.333. If we use the exact same simulation of virtual participants and calculate the SD in the 4-year change from baseline values, it is 0.85. As a heuristic argument, to create the same standard error in the change from baseline at 4 years , one would need to enroll 6.52 participants for the MMRM relative to 1 for the cognitive DPM (a SD of 0.33).

We have simulated a wide range of different scenarios around the assumption of the natural decline, variability, accrual rates, and drop-out rates and displayed the robustness of the model to these changes in assumptions. In all the scenarios we investigated, the DPM led to large increases in power compared with the typical MMRM model (results not shown).

3 | DISCUSSION

Having research participants that are before onset, yet are destined to develop AD, and at a very predictable time, while tragic, provides an incredible scientific opportunity for developing disease-modifying therapies. While the ability to characterize those that will get AD allows studying the disease before onset, the ability to characterize the time of onset and the decline rate before and after onset makes an enormous difference in the ability to learn from prevention trials. We present a flexible cognitive DPM that provides a strong characterization of the cognitive decline of ADAD mutation carriers in the DIAN observational cohort. The model demonstrates the highly consistent behavior of cognitive decline and has been extended to estimate effects of potential disease modifying treatment effects. The model provides tremendous power increases—for example, it allows detection of a potential treatment effect with 80 ADAD patients compared with what normally would take more than 400 ADAD patients. We show that the cognitive DPM accounts for the heterogeneity between trial participants and efficiently uses the outcome assessment in the extended follow-up, and thus reduces the required sample size to achieve sufficient power for clinical trials compared with common alternative approaches. In addition, the DPM allows for characterizing a clinically relevant estimate of effect size.

The cognitive DPM is developed based on a particular cognitive composite, but it is not restricted to this unique composite. Any composite or any single cognitive measurement can potentially be used with in a similar model. A similar DPM could be used on a variety of endpoints as long as their behavior exhibits progressive decline. Furthermore, the DPM could be extended to jointly model multiple outcomes by assuming individual random effects for each outcome to share a multivariate normal distribution with a common age of onset and by using the same proportion for the treatment effect.

The model provides additional inferential strength based on the extended length of follow-up of some participants beyond 4 years based on the assumption of a proportional treatment effect. This is a desirable aspect of analyzing a progressive disease—the most valuable information is from those participants with the longest exposure. Many alternative analysis models, like the MMRM, do not increase their inferential strength when participants have extended followup. Using a proportional treatment effect to the rate of decline and using extended follow-up can be used in sporadic AD trials. For example, the change since baseline in ADAS-cog 116 and in ADAS-cog 1424 in mild AD in EXPEDITION1 and EXPEDITION2 trials and the decline over time in standardized MMSE and in Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale in the trial for donepezil and memantine11 indicated approximately proportional treatment effects from baseline to the end of study. But, without a reliable estimate of the age of onset in the preclinical stage, the ability to use a DPM with time based on EYO remains elusive in sporadic AD trials. Methods that can be potentially used to find an estimated age of onset for sporadic AD have been proposed.25

The delayed-start design (also referred to as the staggering-start design) has been considered in designs to demonstrate disease-modifying treatment effects.24,26,27 The cognitive DPM can be easily modified to analyze a treatment effect in a delayed start design by incorporating the starting time of each treatment as a function of the delayed start.

Compared with other well-established mixed effects models like the MMRM using time since baseline as a categorical variable,6,11,12 our model uses a stronger assumption of the proportional treatment effect, but this assumption can be relaxed by partitioning participants into different stages and then using multiple proportional treatment effects. Another assumption in our model is that we assumed a monotonic decline in the cognition over time. Although some individuals may violate this assumption in short random fluctuations, the monotonic decline has clear face validity in this population as there is essentially complete penetrance of these mutations leading to an inevitable cognitive decline. We have extended the model to allow parameters of “a learning curve” on the early visits after treatment. This allows the model to estimate a bump that may occur based on learning how to do well on the cognitive tests through practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding information

NIH, Grant/Award Numbers: R01AG146179, R56AG053267 and U01AG042791; NIA, Grant/Award Number: U19 AG032438

The DIAN observational study is supported by NIA grant U19 AG032438. We gratefully acknowledge the altruism of the participants and their families. The DIAN-TU trial is supported by NIH grants U01AG042791, R01AG146179, and R56AG053267. DIAN-TU Pharma Consortium has supports from AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Eisai, Janssen, Eli Lilly & Company/Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Hoffman La-Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, and Sanofi. We are also grateful to GHR Foundation and Alzheimer’s Association for their continuous support and advocacy of the DIAN study and the DIAN-TU trial.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

References

- 1.Rafii MS, Aisen PS. Recent developments in Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. BMC Med. 2009;7(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider LS, Mangialasche F, Andreasen N, et al. Clinical trials and late-stage drug development for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal from 1984 to 2014. J Intern Med. 2014;275(3):251–283. doi: 10.1111/joim.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummings JL. Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease drug development. Chicago, IL 60654: Elsevier; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, et al. The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(8):961–970. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bateman RJ, Benzinger TL, Berry S, et al. The DIAN–TU next generation Alzheimer’s prevention trial: adaptive design and disease progression model. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(1):8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, et al. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):311–321. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):322–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G, Kennedy RE, Cutter GR, Schneider LS. Effect of sample size re-estimation in adaptive clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interventions. 2015;1(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vellas B, Carrillo MC, Sampaio C, et al. Designing drug trials for Alzheimer’s disease: what we have learned from the release of the phase III antibody trials: a report from the EU/US/CTAD Task Force. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(4):438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy RE, Cutter GR, Wang G, Schneider LS. Using baseline cognitive severity for enriching Alzheimer’s disease clinical trials: how does Mini-Mental State Examination predict rate of change? Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interventions. 2015;1(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard R, McShane R, Lindesay J, et al. Donepezil and memantine for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):893–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Honig LS, Vellas B, Woodward M, et al. Trial of solanezumab for mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):321–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bateman RJ, Aisen PS, De Strooper B, et al. Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a review and proposal for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res Ther. 2011;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/alzrt59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ryman DC, Acosta-Baena N, Aisen PS, et al. Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;83(3):253–260. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiong C, van Belle G, Chen K, et al. Combining multiple markers to improve the longitudinal rate of progression: application to clinical trials on the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Stat Biopharm Res. 2013;5(1):54–66. doi: 10.1080/19466315.2012.756662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrington KD, Lim YY, Ames D, et al. Using robust normative data to investigate the neuropsychology of cognitive aging. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2016;32:142–154. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acw106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassenstab J, Chasse R, Grabow P, et al. Certified normal: Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers and normative estimates of cognitive functioning. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;43:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiman EM, Langbaum JB, Tariot PN, et al. CAP [mdash] advancing the evaluation of preclinical Alzheimer disease treatments. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Storandt M, Balota DA, Aschenbrenner AJ, Morris JC. Clinical and psychological characteristics of the initial cohort of the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) Neuropsychology. 2014;28(1):19–29. doi: 10.1037/neu0000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelfand AE, Smith AF. Sampling-based approaches to calculating marginal densities. J Am Stat Assoc. 1990;85(410):398–409. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metropolis N, Rosenbluth AW, Rosenbluth MN, Teller AH, Teller E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J Chem Phys. 1953;21(6):1087–1092. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS: a practical guide. Cary, NC 27513–2414, USA: Sas Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu-Seifert H, Andersen SW, Lipkovich I, Holdridge KC, Siemers E. A novel approach to delayed-start analyses for demonstrating disease-modifying effects in Alzheimer’s disease. PloS one. 2015;10(3):e0119632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donohue MC, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Le Goff M, et al. Estimating long-term multivariate progression from short-term data. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(5):S400–S410. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Agostino RB., Sr The delayed-start study design. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(13):1304–1306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsm0904209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong C, van Belle G, Miller JP, Morris JC. Designing clinical trials to test disease-modifying agents: application to the treatment trials of Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Trials. 2011;8(1):15–26. doi: 10.1177/1740774510392391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.