Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Despite increasing attention to the use of Shared Decision-Making (SDM) in the Emergency Department (ED), little is known about ED patients’ perspectives regarding this practice. We sought to explore the use of SDM from the perspectives of ED patients, focusing on what affects patients’ desired level of involvement and what barriers and facilitators patients find most relevant to their experience.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of ED patients or their proxies at two sites. An interview guide was developed from existing literature and expert consensus, and based on a framework underscoring the importance of both knowledge and power. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and analyzed in an iterative process by a 3-person coding team. Emergent themes were identified, discussed, and organized.

Results:

Twenty-nine patients and proxies participated. The mean age of participants was 56 years (range 20 to 89), and 13 were female. Participants were diverse in regards to race/ethnicity, education, number of previous ED visits, and presence of chronic conditions. All participants wanted some degree of involvement in decision-making. Participants who made statements suggesting high self-efficacy and those who expressed mistrust of the healthcare system or previous negative experiences wanted a greater degree of involvement. Facilitators to involvement included familiarity with the decision at hand, physicians’ good communication skills, and clearly-delineated options. Some participants felt that their own relative lack of knowledge, compared to that of the physicians, made their involvement inappropriate or unwanted. Many participants had no expectation for SDM and although they did want involvement when asked explicitly, were otherwise likely to defer to physicians without discussion. Many did not recognize opportunities for SDM in their clinical care.

Conclusions:

This exploration of ED patients’ perceptions of SDM suggests that most patients want some degree of involvement in medical decision-making but more proactive engagement of patients by clinicians is often needed. Further research should examine these issues in a larger and more representative population.

Keywords: shared decision-making, patients’ perspectives, qualitative research, patient-centered care, patient engagement

Introduction

Shared Decision-making (SDM) has been described as “an approach where clinicians and patients share the best available evidence when faced with the task of making decisions,” not only sharing information, but working together to come to a decision informed by the physician’s expertise and the patient’s values and goals, needs and preferences, and risk tolerance.1 A recently published framework suggests that only 3 factors are necessary for SDM to be appropriate in the ED: some degree of clinical equipoise, a willing and able patient or proxy, and time.2 Although research in the field of SDM has been ongoing for several decades, recent attention to the opportunities for SDM in the Emergency Department (ED) has heightened the need for ED-specific research. 3,4 Several studies have examined SDM from the perspective of the ED physician, recognizing the importance of the physician-as-stakeholder.5–7 These studies have found that physicians often believe their patients do not want to be involved in decisions in the setting of emergency care.5,6 However, no studies have examined SDM from the point of view of the ED patient.

Numerous qualitative and quantitative studies have examined patients’ perceptions, attitudes, and preferences outside of the context of emergency care.8–11 A recent systematic review examined patients’ perspectives on SDM in primary and secondary care settings both within and outside the United States. The authors reported that patients needed knowledge, about their condition and their options, as well as power, in the setting of the power-imbalance of the physician-patient relationship, to be able to fully participate in SDM.11 This review also suggested that patients may believe that SDM is more difficult to achieve in the ED compared to other settings due to factors such as not knowing the physician, lack of trust, lack of time, lack of privacy, the severity/importance of the decision, and concern over being labeled as “difficult.”11 Many of these factors are theoretically more common in the setting of ED care as compared to outpatient primary care.

Patients in the ED are often in a different physical and emotional condition compared to patients in an office setting, making it important to understand the unique perspectives of ED patients regarding SDM. In order to extend current understanding of SDM in the ED, we addressed the following questions: 1. Do ED patients want to be involved in medical decision-making during an ED encounter? 2. What factors affect their desired level of involvement? and 3. What barriers and facilitators to SDM in the ED do patients identify? In order to fully explore these questions, we decided to begin with a qualitative approach.

Methods

Study Design and Interview Guide

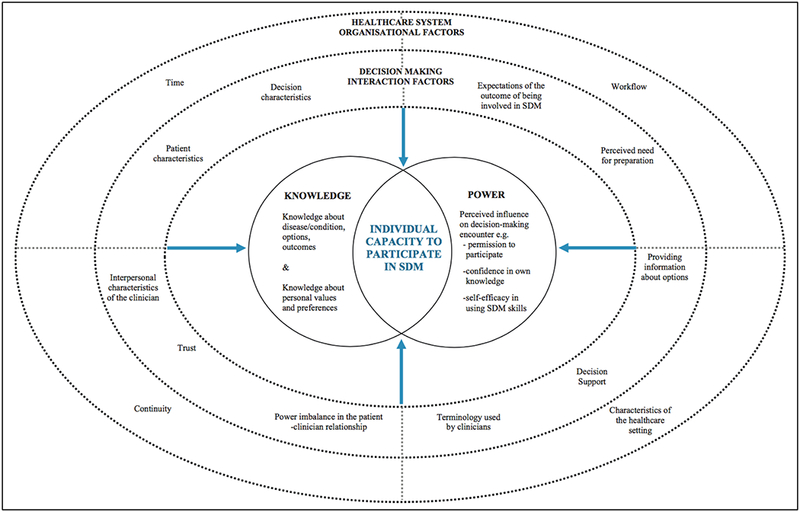

We conducted semi-structured interviews with a purposive sample of ED patients or their proxies using an interview guide developed by the investigators. The interview guide drew upon a framework detailed in a recent systematic review of patients’ perceptions of SDM (Figure 1) and is available in Supplement A.11 The interview started with questions about the patient’s experience during that ED visit. Then the interviewer asked about whether the patient could think of a time when a doctor made it clear that there was more than one option for their care, in the ED or otherwise. After prompts to explore the answers, the concept of SDM was explained, and comprehension checked via the teach-back method. If the patient did not seem to fully grasp the concept, it was re-explained and understanding re-checked. After providing this definition of SDM, patients were asked again about previous experiences making decisions together with doctors. These experiences helped the interviewers explore the barriers and facilitators as perceived by the patients. Lastly, the patients were presented with three scenarios (Appendix Table 2) and asked whether they would want to be involved with decision-making if they were faced with that scenario. These particular scenarios were chosen because they were common and simple enough to explain, but different enough to facilitate further exploratory questions. This allowed interviewers to explore factors that may change participants’ desired level of involvement. The guide was revised over the course of the first six interviews. Notable changes included increasing the detail in the scenarios presented. The study was granted exempt status by the local Institutional Review Board, and was designed to comply with standards for qualitative research.12–14

Figure 1.

Knowledge and power: patient-reported influences on individual capacity to participate in shared decision making (reproduced with permission from Joseph-Williams et al.)

Reprinted from Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Education and Counseling 2014;94(3):291-309, with permission from Elsevier

Study Setting and Population

The research team approached a purposive sample of clinically stable ED patients (i.e. not requiring constant nursing or clinician presence) or their proxies, aiming for variation in sex, age, race/ethnicity, primary language, experience with ED care, chronic medical conditions, and disposition (admission versus discharge). Potential participants were approached after their clinician confirmed they were hemodynamically stable, did not require acute interventions, spoke conversational English, and were not immediately leaving the department for testing, admission or discharge. Patients were approached in two different EDs in New England. The first ED is an urban, academic, tertiary care, level 1 trauma center with >115,000 visits/year. The second ED is a community site located in a rural community, with <30,000 visits/year.

Data Collection and Analysis

Participants were approached in private ED rooms by one or two members of the research team. The study was explained, written informed consent was obtained, and interviews took place in private rooms. Family members or friends accompanying the patient or proxy were allowed to stay and add commentary at the discretion of the interviewee; these people did not sign informed consent, but were present for the consenting process and were aware that their participation was voluntary. When a patient did not have decision-making capacity, the interviewee was the proxy, and signed informed consent, with the idea that in the setting of a clinical decision, they would be the person engaging in SDM regarding the patient’s care.

Initial interviews were performed with two members of the research team present (ES and GD), with one member taking notes. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed (discussion not related to involvement in decision-making was not transcribed). Transcripts were entered into Dedoose qualitative data management and analysis software (Dedoose Version 7.0.18 Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC). Three trained members of the research team coded transcripts and field notes using a directed approach to qualitative content analysis: that is, we combined a priori codes drawn from the literature and our framework (Figure 1) with emergent themes.15 Prior to coding transcripts, each team member listened to the interview they were about to code in order to better understand the nuances of the conversation. Coding of transcripts was performed iteratively and concurrently with subsequent interviews; transcripts were re-coded as the codebook was revised. Each of the three coders coded each transcript at least once, resolving differences through consensus. Interviews were conducted until goals for participant heterogeneity were achieved and theoretical saturation was reached (few new themes emerged from final four interviews).16 The codebook is available in Supplement B.

Research team and reflexivity

Interviews were conducted by a female attending EP (ES) and a female senior EM resident (GD). ES had experience with qualitative methods and GD received training and observed six interviews prior to independently interviewing. Interviewers were not working clinically at the times of the interviews and did not have a relationship with participants outside of the interview. The three coders were all practicing EPs (attendings or residents).

Results

We approached 43 patients or proxies at two different Emergency Departments in New England. Fourteen refused because they were “too tired,” “not feeling well,” or being discharged. Twenty-nine patients/proxies consented to interviews. Participants represented a diverse range of demographic characteristics (Table 1). Approximately half of interviewees had friends or family present who offered commentary (demographics not recorded).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Participant Characteristics (N=29) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age - mean (range) | 56 (20 – 89) |

| Female | 13 (45%) |

| Proxy | 2 (7%) |

| Self-identified race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 18 (62%) |

| African American | 6 (21%) |

| Hispanic | 4 (14%) |

| Multi-racial | 1 (3%) |

| Level of education | |

| Some high school (did not complete) | 4 (14%) |

| High school graduate or GED | 12 (41%) |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 8 (28%) |

| 4-year college graduate | 1 (3%) |

| More than 4-year college degree | 3 (10%) |

| Did not answer | 1 (3%) |

| Language spoken at home | |

| Primarily English | 27 (93%) |

| Primarily Spanish | 2 (7%) |

| Prior experience w/ SDM | |

| Shared an experience during interview | 20 (69%) |

| Unable to recall an experience with SDM | 9 (31%) |

| Insurance | |

| Private | 11 (38%) |

| Medicare | 5 (17%) |

| Medicaid | 9 (31%) |

| Other/did not answer | 4 (14%) |

| Disposition | |

| Admission | 17 (59%) |

| Discharge | 7 (24%) |

| Don’t know | 5 (17%) |

1. Do ED patients want to be involved in medical decision-making during an ED encounter?

The majority of participants wanted to be involved in decisions both with their primary doctor and in the ED. Nearly all participants felt comfortable asking a doctor to explain things, but a smaller proportion were comfortable disagreeing with a doctor. When presented with the hypothetical scenarios, the majority of participants continued to want to be involved in decisions. All participants wanted to be involved in at least one of the hypothetical decisions discussed. (Appendix Tables 1 and 2)

2. What factors affect patients’ desired level of involvement?

Participants identified a number of factors that influenced whether or not they wanted to be involved in a particular decision (Table 2). Some of these factors both affected their desire and their ability to be involved (Table 3).

Table 2.

Self-reported factors that affected participants’ desired level of involvement

| Factors that increase desire for involvement | Representative Quotes (participant demographics*) (Example Question: What is it about this situation that makes you want to be involved?) |

|

| Patient-Level Factors and Previous Experiences | Past experiences with poor outcomes, unsatisfying care, or mistrust of the physician or system |

Sometimes doctors are wrong (37-year-old Hispanic female) [Regarding chest pain admission scenario] I would want to be involved and I’d want further tests. There are a lot of people … that want that hospital shut down [for safety]. (69-year-old White male) She could have gone home and died. So the main concern is obviously listening to the patient, and not assuming that, you know, doctor knows best all the time. (Family member of 69-year-old Black female) |

| Situation Characteristics | Severity of illness | (If) somebody’s uncomfortable - they want to know what’s going on. (87-year-old White male) |

| A clear understanding of the consequences | I tell him [the doctor], ‘Please, tell me [about the options]. Let me know what’s going on. But I have to understand you. Because, if I don’t understand you, I can’t answer my questions.’ (44-year-old Hispanic male) | |

| Factors that decrease desire for involvement | Representative Quotes (Example Question What is it about this situation that makes you want less involvement in decisions?) |

|

| Patient-Level Factors and Previous Experiences | Anxiety | It gives me anxiety, (to talk about choices). Like, I don’t know! (29-year-old Hispanic male) |

| Situation characteristics | Setting of ED/ Severity of illness |

I think basically if I’m in the ER I will be less able to make a decision. You have a serious problem if you are in here. (86-year-old Caucasian female) [Regarding scenarios] It would depend on how serious the situation was. If nothing seemed serious and they were just waiting to do it again to make sure… I would want them to let me help to make the decision. If I was really having a heart attack obviously they should make the decision. [If it was really serious, you’d defer to them, but if it was safe either way, would you want to be involved?] Yes. (86-year-old Caucasian female) |

| Consequences poorly understood or deemed trivial | [Regarding scenarios] I’d let the doctor (make that decision about CT or ultrasound) I don’t know what I need, I would want to know what does one (test) do that the other doesn’t. (37-year-old Hispanic female) I could care less. Just figure out what’s wrong. Is it really that big of a deal between a CT and an ultrasound? (53-year-old Black male) |

|

Table 3.

Factors that participants described as potential barriers or facilitators

| FACILITATORS | Representative Quotes (Example Questions: What made that SDM conversation go well? What could have helped you be involved? What helps you have this conversation?]) |

||

| Physician Characteristics and Behavior | Physician is a good communicator: good at listening and explaining the consequences of available options. | [Explaining a situation when SDM went well] I asked the doctor some of the questions about which could be better, and the doctor went through the benefits, and we made a choice of which one (medication) to use. (63-year-old White male) I just like how he explained everything. He explained it so I could understand it (48-year-old White male) [What would be your advice to doctors?] Well, just be down to earth. Speak…Down to earth talk. Basic talk. (87-year-old White male) Come and talk to us more directly instead of talking doctor…come and speak to us in English and tell us…what’s going on, instead of speaking in their own language. (44-year-old Hispanic male) [What helps you have this conversation?] Depends on the doctor. How comfortable they make you feel, you can even tell the way they greet…the way they talk, how concerned they are, how they explain things (37-year-old Hispanic female) |

|

| Physician makes it explicitly clear that a decision needs to be made and invites patient to be involved. |

This is what I think would be good: To say, we [have to make] a decision, and we want to get your input on it. (61-year-old African-American female) I think doctors need to let patients know that they have options, that they have a choice. I mean, I don’t know what’s going on. It’s up to the doctor and the nurses to let you know, you have these options, and present each option and tell you the pros and the cons of each one and help the patient decide which one would be best for them. (53-year-old Black male) |

||

| Physician is humble and accepting of patient input. | The main concern is obviously listening to the patient, and not assuming that the doctor knows best all the time. (Family of 69-year-old Black female) | ||

| Patient-Level Factors and Previous Experiences | Patient feels empowered and recognizes self-efficacy. |

I think it’s something inside me. Courage? You know. Yes, the doctor is a professional, I don’t know that much about medication, but I do know the effect that it has on me. So, if I’m not feeling good about the effects, then I don’t want to take it. (61-year-old African-American female) If I did have a disagreement with a doctor, the first thing I’d do (I’d say,) ‘Would you please explain to me what you mean by that statement?’ (63-year-old White male) This is my life, and I need to be able to make that decision because they are not the one who is suffering. I am the one that is suffering. (69-year-old Black female) |

|

| Patient reports previous experience or baseline understanding (of medicine, their body, or the medical system). | [Did you ever have a doctor that you didn’t feel comfortable disagreeing with?] No. No, this is my second home. I’ve been here, you could say, all my life. (44-year-old Hispanic male with chronic medical problems) …some people are not outspoken, I’m a medical assistant, I know what’s going on. (37-year-old Hispanic female) If I don’t agree with them, I would speak up. When my mother was alive I had to deal with her and the Alzheimer’s and the dialysis and all this other stuff. I had to speak up for her. Speaking up comes from my experience with my mother. I also work with handicapped people and you need to speak up for that. (56-year-old multi-racial female) |

||

| Situation Characteristics | Presence of an advocate | [When she’s around (patient’s fiancée), does that help you be more involved in this?] Oh yes, I love it. I love it, because she understands it and she tells me. (44-year-old Hispanic male) I like to have someone else there. (25-year-old White female) It’s hard to be an advocate for yourself when you’re by yourself. It would be easier if you had someone here for you. (23-year-old African-American female) |

|

| BARRIERS | Representative Quotes (Example Questions: What makes it harder to have these conversations? What makes SDM less likely to happen?) |

||

| Physician Characteristics and Behavior | Physician is a poor communicator or uses medical jargon. | [What makes it harder to have these conversations?] If they don’t listen, if they’re kind of turning you off and if you can tell that they’re turning you off. (86-year-old Caucasian female) It was like he wasn’t listening to me at all. (69-year-old White male) [What would be your advice to doctors?] I don’t know. Teach people how to do them better (conversations). She (the doctor) was talking to me like I was a little kid. (69-year-old White male) |

|

| Physician is authoritative, doesn’t want input, and doesn’t give weight to patient’s experience. |

My wife is right there. She knows the questions to ask. A lot of doctors don’t like it. I don’t think they like being told what to do. They think they’re being bothered. (69-year-old White male) They have to give us credit, I know my body, I’m a day or 2 away (from severe urinary retention).. I’m afraid of that… I don’t think they believe me, I know this whole process, I know exactly (what’s going to happen). (58-year-old White male) (Regarding bad experience) He tends to like to educate and let everybody know how smart he is about absolutely everything instead of dealing with what he’s supposed to be dealing with. He just has his own opinion on how everything should be, and talks over you, and doesn’t care what you have to say. Nor does he ever listen to what you have to say. (Proxy for 88-year-old White female) [Interviewer: You don’t have SDM with your PCP?] She says, ‘I’m gonna write you a prescription for this’, and I say I don’t like that. She says, ‘Oh, come on! Take it!’” [she doesn’t like being disagreed with?] She don’t. Like ‘I’m the doctor.’ (61-year-old African-American female) So, in her particular case, the patient knew better than the doctor. But the doctor ignored the patient. (Family of 69-year-old Black female) |

||

| Physician responds negatively to patient bringing outside information. | With the internet, doctors in my opinion, maybe feel that people are getting stuff off the internet and think they’re experts and they take that the wrong way and are a little dismissive because of that…I actually did that with my primary care doctor… [how’d he take it] He’s a nice guy, it wasn’t that he wasn’t receptive, but he was like, ugh, really? (51-year-old White male) | ||

| Physician is stressed or busy. | [What could WE (the doctors, nurses, hospital) do to help you be involved?] I don’t know, this is a busy place. There were a lot of people without rooms. Make this place bigger. Put more nurses and doctors on so people aren’t (so) stressed and busy that they can’t provide individual care to the patients. (53-year-old Black male) [Do you feel like he answered your questions?] Yeah. [Yeah? You sound kind of hesitant in that ‘yeah’] Yeah. Because he did, but … it seemed like he was in a rush to answer them. (24-year-old White female) |

||

| Patient-Level Factors and Previous Experiences | Patient does not feel knowledgeable enough or empowered and would not initiate a discussion. Patient defers to physicians’ expertise and minimizes the utility of their input. |

I mean I’m not the professional. I didn’t go to school for this. I don’t know what I could do or what should be… This is what they do. They do this day in and day out. And I don’t. (48-year-old White male) How can you make a decision when you’re not an expert?... The bottom line is I am not a doctor. (63-year-old White female) When I come to see my doc, my regular doctor, she sits down and she talks to me…I don’t just jump in and say, ‘Oh, is this better? Or why can’t we do it this way?’ (44-year-old Hispanic male) [If you disagree with the doctor, would you tell them?] Maybe, but they are the doctor – I’m just the sick person... I will never know what these people know, I don’t want them waiting on me for answers, I want them to do their job. (20-year-old White female) I don’t want to bug a doctor, but I do like that conversation about diagnosis and treatment with options. (59-year-old White male) I pretty much assume my doctor knows what the hell they’re talking about. Because what do I know? (53-year-old Black male) I don’t think we get any decision-making with our doctor, he makes them and we go along with him. We figure he knows more than we do. (Partner of 80-year-old White female) They are the ones that decide what’s right for me. I don’t understand what’s going on with me…I don’t know how to read their cat scans and nothing like that. (44-year-old Hispanic male) |

|

| Situation characteristics | (Example Question: How does being in the Emergency Department, as opposed to the doctor’s office or the rest of the hospital, change your desire or ability to be involved with decisions?) | ||

| ED-related setting challenges | Multiple providers | [Interviewer paraphrasing: You think it’s harder in the ED?] There’s a lot of people. The shifts are different… if you’re here for 8 hours, you might have two or three nurses, you might see two or three docs, depending on when they change shifts. There’s always something that could potentially get lost in the handover... (pause) plus down here it’s very stressful. You’re here, you don’t know what’s going on. You’re here obviously because it’s an emergency. (Proxy for 88-year-old White female) | |

| Waiting times | Sometimes the waiting time, I believe, could be sort of discouraging to the patient. (87-year-old White male) | ||

| Stressful environment | [You think it’s harder in the ED?] It’s more stressful being at the ED than at a regular doctor’s office, because you’re not expecting what’s going wrong. (63-year-old White male) I think this could be an overwhelming experience. Some people can see the doctor as THE doctor and they know everything, but maybe you need to talk it out a little bit. Maybe it can be overwhelming (37-year-old White female) |

||

| Lack of Privacy | [Regarding the challenges of having an SDM conversation] I had no (room). I was in the hallway. Kind of sucks being in the hallway. There’s no privacy. (53-year-old Black male) | ||

| Lack of relationship with the doctor | There’s lots of people, you don’t really know who everyone is. (37-year-old White female) | ||

| Time Constraints |

Sometimes the doctor seems busy so you are afraid to bother them. It’s easier with primary care doctor because you’ve scheduled time with them, in the ED they have lots of other people to see. (20-year-old White female) It’s too busy in here, people are doing things. They don’t have time to sit down and talk to everybody all night. And like I said, the patients are not informed so it may take awhile to hold that conversation. You have other patients; you can’t spend forever with one person. (53-year-old Black male) |

||

| Consequences of decision are scary, confusing or complex |

Maybe sometimes I’m afraid to say something because it will be something worse than I think it is. [You don’t want to bring it up because you’re afraid you might get bad news?] Yes. (86-year-old Caucasian female) [Regarding admission for CHF] I would be scared to make that decision [but regarding surgery versus injection for trigger finger, you were ok with that decision?] That was easy, I understand the consequences. (63-year-old White female) |

||

| Severity of illness |

I think basically if I’m in the ER I will be less able to make a decision. You have a serious problem if you are in here. (86-year-old Caucasian female) Usually you’re so sick you just want them to take care of you and do their best. (80-year-old White female) |

||

Racial identification was by free-text self-report, hence the variation in racial and ethnic descriptions.

FACTORS THAT INCREASED DESIRE FOR INVOLVEMENT

Patient-Level Factors and Previous Experiences

A number of participants noted that previous experiences with what they deemed unsatisfying care or actual medical errors had encouraged them to be more involved in their own care. (“I would like to be involved more [here in the ED] because I feel like they are careless here, and it’s an issue here…I have to make sure I’m on my game more.” 23-year-old African-American female with chronic medical condition)

Situational Characteristics

Many participants noted that the more serious the illness, the more involvement they would want. Some also noted that when they understood the decision at hand, such as in the case of a decision they had faced previously (i.e. admission), they were more likely to want involvement.

FACTORS THAT DECREASED DESIRE FOR INVOLVEMENT

Patient-Level Factors and Previous Experiences

Two participants mentioned that being involved with medical decisions made them anxious, and several noted that if they were in severe pain, they might not want to be involved.

Situation Characteristics

Although many participants, as noted above, wanted more involvement if they were seriously ill, others noted that as their illness severity increased, their desire for involvement went down. Many participants made it clear that when they did not understand the consequences of the decision at hand, or they felt the consequences were trivial, they did not care to be involved.

3. What are the patient-perceived barriers and facilitators to SDM in the ED?

Participants identified many factors that contribute to their ability to be involved in medical decisions, and the majority of these factors could be grouped in the categories of physician characteristics and behavior, patient-level characteristics and previous experiences, and situation characteristics (Table 3).

FACILITATORS

Physician Characteristics and Behavior

Participants consistently noted that SDM would be easier with physicians who had good communication skills, i.e., who were both good listeners and good “explainers.” They noted that they wanted clear explanations not just of the options, but also of the potential consequences of their decisions. Similarly, a number of participants noted that they would prefer the physician to explicitly invite their involvement, as they would otherwise not push for it, both because they felt that the physician was the expert and because it wasn’t clear to them when it was appropriate for them to be involved. (“This is what I think would be good: to say we [have to make] a decision, and we want to get your input on it.” 61-year-old African-American woman being treated for sepsis)

Patient-Level Factors and Previous Experiences

Participants often recognized that their own empowerment and self-efficacy, from baseline knowledge or previous experiences, was a facilitator. They discussed past experiences advocating for themselves or others and how they learned to be comfortable having medical conversations and navigating the power imbalance. (“...this thing has been going on for years, so I understand it.” 69-year-old Black female being seen for GI bleed)

Lastly, several noted that because they worked in the medical field (or a family member did), this made it easier to be involved. (“I can advocate for myself because I’ve had to do it for others.” 37-year-old White female being evaluated for a head injury)

Situation Characteristics

Participants noted that having a friend or family member present was a huge help to them in conversations with clinicians – this person could advocate, ask questions, and support the patient. Many noted that they had experience advocating for friends and family, due to their comfort with the healthcare system.

BARRIERS

Physician Characteristics and Behavior

Nearly every participant spoke about both positive and negative experiences with physicians, focusing on communication skills, such as the use of medical jargon and bedside manner. Participants noted that they felt that physicians were sometimes poor listeners and poor communicators, and maybe they could be taught to be better at having SDM conversations.

A sizable number of participants recounted experiences where doctors had made it clear that they were uninterested in either the patient’s opinion or the patient’s attempt to bring in outside information. Several noted clinicians or nurses being dismissive of medical knowledge they brought to the encounter. For example, a participant who had recently stopped his Coumadin after knee surgery presented with chest pain and shortness of breath. He informed the triage nurse he was concerned he might have a pulmonary embolism because his symptoms matched what he had read on the internet, and he was warned about the “misinformation on the internet.” He was subsequently found to have an embolism, and relayed this story as an example of the system’s lack of respect for patient input.

Participants noted that ED clinicians in particular may be rushed. While several noted this sympathetically, recognizing that there were many patients requiring care, many found this to be a barrier to a thoughtful exchange of information.

Patient-Level Factors and Previous Experiences

The most prevalent themes regarding patient-level factors were the inter-related themes of lack of empowerment, relative lack of knowledge, and deference to physicians’ expertise. Although the majority of participants spoke about the importance of empowerment or gave examples of their own self-efficacy, the concept of deference to the experts or acknowledgement of their own relative lack of knowledge was also endorsed by a majority of participants. Specifically, many subjects spoke of how they were willing and interested in being involved with decisions, but would never initiate a discussion about potential options. In short, though they wanted to be involved, they preferred an explicit invitation so they knew when their involvement was appropriate. (“I will never know what these people know, I don’t want them waiting on me for answers, I want them to do their job.” 20-year-old white female with no chronic conditions) and (“I don’t want to bug a doctor, but I do like that conversation about diagnosis and treatment with options.” 59-year-old White male being admitted for atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response).

Situational Characteristics

Asked how the ED setting affected their ability to participate in SDM conversations, participants noted that many of the common challenges of being a patient in the ED would hinder SDM: waiting times, lack of privacy, multiple providers, the uncertainty of their clinical situation, time constraints, and the severity of their illness. Only a few participants felt that fear about the consequences of the decision would prevent their involvement.

4. Non-verbal qualitative analysis

While our interviews aimed to understand the barriers and facilitators to the use of SDM from the point of view of the ED patient, a number of relevant themes emerged from our interactions as interviewers.

FACILITATORS

First, we noticed that over the course of discussing SDM and asking questions, several participants who started the interview hesitant about their own involvement in decisions seemed to become more interested, as if our discussion of patient-involvement gave them “permission” to be involved. This was generally most notable in participants who clearly endorsed general deference to medical authority.

Second, we noted that when more detailed descriptions were given for hypothetical scenarios, participants were more interested in being part of decision-making.

BARRIERS

As part of the introduction of the interview, we asked participants about their care team and providers during that visit and found that approximately half of our sample didn’t know their clinicians’ name, with a sizable minority unable to describe them (such as their gender). Interviewers recognized this as a barrier to the good communication needed for SDM. We also noted that a sizable minority had never had any experiences with SDM and did not expect it at all, from any doctor. More than one responded to the questions about their previous SDM experiences with surprise, exemplified by one respondent: “Not my doctor! I’ve never had that happen.” (61-year-old African-American female).

Interviewers also noted that participants were often unaware that there may have been decisions being made that they could have been involved with during their visit. For example, a 50-year-old woman being admitted for observation for low risk chest pain – a common scenario for SDM – told interviewers that there were not two options, she had to be admitted.

A few participants seemed completely disengaged from both the interview and their medical care (such as keeping eyes closed during the interview, giving short answers, not making eye contact), but when asked directly about their desire for involvement, responded very clearly that they would want to be involved with all medical decisions about their care.

Lastly, the interviewers noted that trust played an interesting role in shaping participants’ involvement: a number of participants noted that their mistrust of the system made them want more involvement. Others reported the inverse of this phenomenon: that they didn’t seek involvement because they trusted the physicians to make the best decisions. In this way, trust was a barrier to patient involvement, and mistrust a facilitator.

Discussion

This is the first evaluation of the attitudes and preferences of ED patients regarding SDM, and a number of important issues are apparent. First, in contrast to what physicians believe, all participants expressed a desire to be involved in some aspects of decision-making, but there was variation regarding what types of decisions they wanted to be involved in.5 This is not surprising given the diverse concerns of the participants: for example, some felt that the decision regarding sutures versus glue for a facial laceration was important to them, others felt this issue was trivial. Second, the interviewers quickly realized that the amount of detail given when asking about desired level of involvement affected the participants’ responses. When scenarios were explained in better detail, participants were more likely to clearly express a desire to be involved. This casts in doubt on one of the proposed first steps to a SDM conversation, that the physician should ask the patient “how they want to be involved in decision-making” early on in the conversation.17,18 Based on our results, this question should come only after significant information exchange or the patient may defer to the physician due to a lack of understanding of the options and consequences.

Regarding barriers and facilitators, although the largest systematic review to date explained that “knowledge does not equal power, both are necessary,” our analysis suggested that many patients who both feel empowered and have respect for their own knowledge are still likely to take a passive role in their interactions with physicians in the setting of ED care.11 This seems to be due to two factors. First, patients often either trusted the physician to make the right decision for them or they simply felt the physician was more qualified. Second, patients often didn’t recognize there were decisions happening that they could be involved in. While they reported that they wanted to be involved if involvement was appropriate, most were unlikely to initiate involvement, and instead would wait for the clinician to explicitly invite them into a discussion. In the ED, it appears that patients may need knowledge, power, and an explicit invitation.

A patient’s “trust in the physician” emerged as having a paradoxical role: many noted that SDM would be easier with a clinician they trusted (often due to good communication skills facilitating both trust and SDM), but they noted that mistrust of physicians or the system made them want more involvement. In this way, while trust could facilitate a good conversation, participants suggested that they would be less likely to advocate for their own involvement when they trusted the physician, and therefore, trust could lead to decreased involvement. This could play a role in promoting physicians’ perception that “many patients prefer the doctors decide what do to.”5

Interviewers noted that disengaged body language could bely a desire for involvement, easily leading a clinician to “misdiagnose” this patient’s desired level of involvement.19 This non-verbal communication might create the misconception that the patient prefers to defer to the physician when in reality this disengagement may reflect the patient’s response to their illness or other personal factors. Notably, a large proportion of participants did not know who their clinician was – this communication failure could create challenges for patients trying to involve themselves in medical decision-making.

Our analysis leaves many unanswered questions. Although our participants were clear in their desire for compassionate and plain-spoken providers, how can providers be sure their patients are actually engaged and not simply deferring? If given explicit invitations to partake in SDM, is it possible that – in the desire be a “good patient” – the pendulum will swing too far in the other direction, and patients will acquiesce to a role in decision-making that they are uncomfortable with? There is unlikely to be a one-size-fits all solution, and efforts to further train physicians in the nuances of SDM are likely worthwhile.20

Limitations

Our interviews were performed at two different hospitals in Massachusetts, with a diverse group of patients and proxies; however, all were clinically stable and able to participate in an interview in English. Interviewing patients in different regions and those who spoke other languages may have broadened the variation in the responses, and it is possible that if these same patients were more acutely ill they would have responded differently to interview questions. Additionally, the concept of SDM was new to many of the participants and it is possible that our explanations influenced their responses. Lastly, as we noted, there was a strong trend of deference to physicians. Although the interviewers attempted to distance themselves from clinical care, both were physicians and this may have influenced responses.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that nearly all stable, adult ED patients want some degree of involvement in decision-making in situations for which there are multiple reasonable options. However, based on our analysis, many patients do not recognize opportunities for involvement and will not ask for involvement, but will wait for a clinicians’ invitation. This invitation should be accompanied by clear and jargon-free explanations of options and consequences, which should come before any question of “how would you like to be involved in this decision?” Clinicians should avoid “misdiagnosing” the patient’s preference for involvement based on patients’ verbal and non-verbal expressions of trust, deference, or disengagement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Kye Poronsky and Christopher Morris.

Grant Funding: The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number UL1TR001064. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Additionally, PKL is supported by K24 HL132008: Research and Mentoring in Comparative Effectiveness and Implementation Science.

Footnotes

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Previous Presentations or Publications:

This analysis was presented at National SAEM 2017

Contributor Information

Elizabeth M. Schoenfeld, Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School – Baystate, Springfield, MA, and a researcher at the Institute for Healthcare Delivery and Population Science at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA..

Sarah L. Goff, Division of General Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School-Baystate and at the Institute for Healthcare Delivery and Population Science at Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA..

Gwendolyn Downs, Department of Emergency Medicine at University of Massachusetts Medical School – Baystate, Springfield, MA, at the time the research was performed.

Robert J. Wenger, Department of Emergency Medicine, at University of Massachusetts Medical School – Baystate, Springfield, MA.

Peter K. Lindenauer, Institute for Healthcare Delivery and Population Science, University of Massachusetts Medical School – Baystate.

Kathleen M. Mazor, Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, and Associate Director of the Meyers Primary Care Institute..

References

- 1.Elwyn G, Coulter A, Laitner S, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ 2010;341:c5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Schoenfeld EM, Menchine MD, Breslin M, Walsh C, et al. Shared Decisionmaking in the Emergency Department: A Guiding Framework for Clinicians. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2017. November;70(5):688–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melnick ER, Probst MA, Schoenfeld E, Collins SP, Breslin M, Walsh C, et al. Development and Testing of Shared Decision Making Interventions for Use in Emergency Care: A Research Agenda. Jang TB, editor. Acad Emerg Med 2016. December;23(12):1346–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanzaria HK, Booker-Vaughns J, Itakura K, Yadav K, Kane BG, Gayer C, et al. Dissemination and Implementation of Shared Decision Making Into Clinical Practice: A Research Agenda. Jang TB, editor. Acad Emerg Med 2016. December 7;23(12):1368–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanzaria HK, Brook RH, Probst MA, Harris D, Berry SH, Hoffman JR. Emergency Physician Perceptions of Shared Decision-making. Acad Emerg Med 2015. March 23;22(4):399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenfeld EM, Goff SL, Elia TR, Khordipour ER, Poronsky KE, Nault KA, et al. The Physician-as-Stakeholder: An Exploratory Qualitative Analysis of Physicians’ Motivations for Using Shared Decision Making in the Emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med 2016. December;23(12):1417–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Frosch DL, Hess EP, Winkel G, Ngai KM, et al. Perceived Appropriateness of Shared Decision-making in the Emergency Department: A Survey Study. Acad Emerg Med 2016. April;23(4):375–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levinson DW, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20(6):531–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R. Patients’ preference for involvement in medical decision making: A narrative review. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006. February;60(2):102–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel SR, Bakken S. Preferences for Participation in Decision Making Among Ethnically Diverse Patients with Anxiety and Depression. Community Ment Health J 2010. June 17;46(5):466–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Education and Counseling. 2014;94(3):291–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research. Acad Med 2014;89(9):1245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider NC, Coates WC, Yarris LM. Taking Your Qualitative Research to the Next Level: A Guide for the Medical Educator. AEM Education and Training. 2017;1(4):368–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh HF. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005. November 1;15(9):1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe LV, O’Brien BC, Rees CE. Shedding the cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ 2016. December 16;51(1):40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elwyn G, Hutchings H, Edwards A, Rapport F, Wensing M, Cheung W-Y, et al. The OPTION scale: measuring the extent that clinicians involve patients in decision-making tasks. Health Expect. 2005;8(1):34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholl I, Kriston L, Dirmaier J, Buchholz A, Härter M. Development and psychometric properties of the Shared Decision Making Questionnaire – physician version (SDM-Q-Doc). Patient Education and Counseling. 2012;88(2):284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012. November 8;345(nov07 6):e6572–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoenfeld EM, Goff SL, Elia TR, Khordipour ER, Poronsky KE, Nault KA, et al. A Qualitative Analysis of Attending Physicians’ Use of Shared Decision-Making: Implications for Resident Education. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2018. February;10(1):43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.