Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate whether prophylactic pregabalin reduces pain experienced with medication abortion.

METHODS

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of women initiating medication abortion with mifepristone and buccal misoprostol up to 70 days of gestation. Participants were randomized to oral pregabalin 300 mg or a placebo immediately prior to misoprostol. The primary outcome was maximum pain on an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS), reported using real-time electronic surveys over 72 hours. Secondary outcomes included pain at each time point, ibuprofen and narcotic usage, side effects, and satisfaction. We estimated that 110 women would be required to have 80% power to detect a difference in pain of 1.3 points.

RESULTS

Between June 2015 and October 2016, 241 women were screened and 110 were randomized (56 pregabalin, 54 placebo). Three were lost to follow-up. The primary outcome of mean maximum pain in the pregabalin group was 5.0 ± 2.6 vs 5.5 ± 2.2 in the placebo group (p=0.32). Excluding medication taken before the study capsule, ibuprofen was used by 64% (35/55) of the pregabalin group vs 87% (45/52) placebo (p<0.01). Narcotics were used by 29% (16/55) of the pregabalin group vs 50% (26/52) placebo (p<0.03). More dizziness (p<0.001), sleepiness (p<0.04), and blurred vision (p<0.05) occurred in the pregabalin group. Satisfaction scores for the analgesic regimen were higher in the pregabalin group (very satisfied: 47% versus 22%; p=0.006).

CONCLUSION

Compared with placebo, 300 mg of pregabalin co-administered with misoprostol during medication abortion did not significantly decrease maximum pain scores. Women who received pregabalin were less likely to require any ibuprofen or narcotic, and were more likely to report higher satisfaction with analgesia, despite an increase in dizziness, sleepiness, and blurred vision.

INTRODUCTION

Between 2011 and 2014, the total abortion rate in the United States declined 12%, while early medical abortions increased from 24 to 31% of all nonhospital abortions.1 Women report experiencing moderate to severe pain during medication abortion, with maximum pain scores ranging from six to eight on an 11-point scale.2–5 Limited data exists regarding the most effective analgesic regimen. Ibuprofen has been found to be superior to acetaminophen,4 though it is not beneficial when used prophylactically.2 A review of pain management during medication abortion revealed that 75% of women also required a narcotic.6 With nationwide goals of reducing narcotic use, we sought to find a non-narcotic option for analgesia during medication abortion.

Pregabalin, a gamma-aminobutyric acid analog, is increasingly used as a preoperative medication to decrease acute pain. Maximum therapeutic effect is achieved in one hour with a half-life of 6 hours.7 The rapid onset of action could be ideal for co-administration with misoprostol, as drug levels would peak at the same time as the misoprostol dissolves. A meta-analysis of pregabalin in gynecologic procedures demonstrated decreased pain scores, analgesic and opioid use, and postoperative nausea and vomiting, with no difference in adverse effects compared with placebo.8

Our primary objective was to evaluate whether 300 mg of pregabalin, co-administered with misoprostol during a medication abortion, reduces maximum pain scores. We also hypothesized pregabalin would decrease the use of adjuvant narcotic pain medication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial at the University of Hawaii Women’s Options Center in Honolulu, Hawaii. We obtained Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Hawaii’s Human Studies Program (#22753) and the trial was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02782169). After consenting to a medication abortion, women were approached about study participation and provided informed written consent. Women received counseling regarding pain expectations with medication abortion prior to being approached about study participation. We did not standardize how providers counseled patients regarding these expectations. Patients took mifepristone 200 mg orally in the office and were given misoprostol 800 mcg to be taken buccally at home 24-48 hours later at a time of their choosing. All women were scheduled for office follow-up with their physician, where no data was collected for this study.

We included women age 18 years or older who had a pregnancy up to and including 70 days gestation, and were willing to receive cellular phone text messages and complete electronic surveys over a 72-hour study period. Women were excluded if they had a contraindication or allergy to ibuprofen, acetaminophen, oxycodone, or pregabalin, a desire for vaginal misoprostol administration, an inability to read English, or participation in this trial during a prior pregnancy. Different routes of misoprostol administration are reported to result in different pain scores and side effects, therefore we limited enrollment to only those women who chose buccal misoprostol administration to standardize this aspect of the medication abortion.9

In choosing a dosage of pregabalin, the meta-analysis of gynecologic procedures used dosages of 100-900 mg and showed a positive net effect.8 A second meta-analysis showed no significant difference between single and repeated dosing, though increased sedation was seen with multiple dosing.10 In an induced acute pain model, the dose of pregabalin needed to decrease pain by 30% was found to be 252 mg, so we chose to study a single dosage of 300 mg.11

Participants were randomized to one capsule of pregabalin 300 mg or a matched placebo to be swallowed immediately prior to buccal placement of misoprostol. A researcher not involved in the conduct of the study used a computer-generated randomization scheme of varied block sizes and placed the allocated study capsule in sequentially numbered bags identified only by study identification number, so as to maintain blinding of participants and researchers. A supply of twelve ibuprofen 800 mg tablets and eight oxycodone with acetaminophen 5/325 mg tablets were dispensed to all participants for analgesia. Participants were advised to take ibuprofen (one tablet every six hours) first, with oxycodone with acetaminophen (one tablet every three to four hours) as needed for breakthrough pain.

Baseline demographics were collected as well as an anticipated maximum pain score for the upcoming abortion on an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS), described as a numbered scale from zero to ten, where zero indicates no pain, and ten indicates the most pain possible. Data was then collected at six specified time points over the 72-hour study period by online survey, starting immediately after taking the study medication capsule and misoprostol. Participants were asked to rate their pain during the medication abortion on an 11-point NRS, to report the type and number of analgesic tablets taken, and to indicate side effects experienced. After completion of the first survey, a text message prompt was sent automatically after 2-, 6-, 12-, 24-, and 72-hours. Each prompt included a link to a new survey that contained the same questions as well as a question about maximal pain on the NRS since the previous survey. A 5-point Likert scale assessed satisfaction with the abortion process and analgesia regimen at 24 hours. Participants who did not provide survey responses were contacted to provide a retrospective report after two and six hours by text message, by phone at 24 hours, and e-mail at 72 hours unless a response was received.

Our primary outcome was maximum pain score on the 11-point NRS. The trial was powered to detect a clinically significant reduction in pain of 1.3 on the 11-point NRS.12,13 The NRS was chosen to provide a pain scale that would look the same when viewed on an electronic device of any size when answering the surveys, as opposed to the size sensitive visual analog scale (VAS). Based on a trial using the same medication abortion and analgesia regimen, we anticipated the maximum pain score in the placebo group to be 7.3 ± 2.2.2 Assuming a normal distribution, a sample size of 92 participants (46 in each arm) had 80% power to detect a difference in mean pain score of 1.3 with a significance level of 0.05 using a two-sided t-test. To account for up to a 20% dropout rate, we enrolled 110 participants. If the data were not normally distributed, 42 participants in each arm would have the same power using the Mann-Whitney U test. Secondary outcomes included pain scores at specific time points, analgesic use (ibuprofen and oxycodone with acetaminophen), side effects experienced, and satisfaction with the abortion process and pain control.

We analyzed all participants who provided a response for maximum pain, either in real time surveys or in retrospective report, whether or not they took the study capsule as directed. Participants who were completely lost to follow-up were excluded from analysis. Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous variables were analyzed with t-tests and Mann-Whitney U tests. Analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 24.

RESULTS

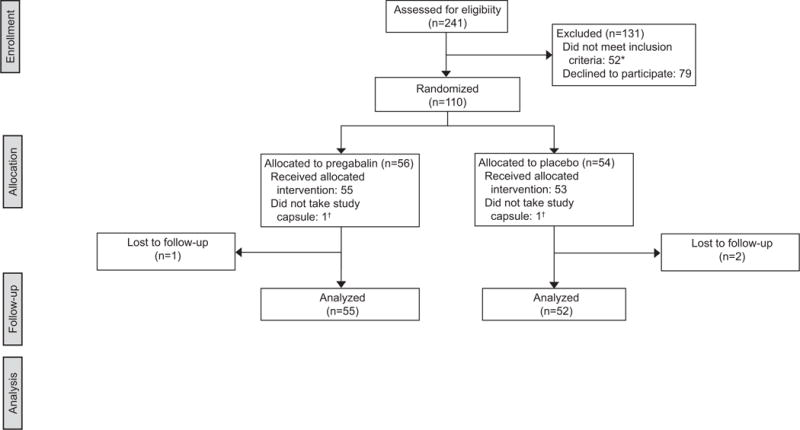

From June 2015 to October 2016, 241 women presenting for medication abortion were screened for inclusion. We enrolled and randomized 110 participants (56 pregabalin and 54 placebo) (Figure 1).. Baseline demographic characteristics were similar between groups (Table 1). The mean age of participants was 27 years (range 18-41), with a mean gestational age of 54 days (range 41-70) by ultrasound. Over 93% of participants completed all six surveys, with over 80% of all responses received within two hours of the requested time. Three women were lost to follow-up (2.7%). Blinding was maintained, with the same proportion of women in each group (59.3%) believing they received pregabalin.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart. *Exclusions: Alternative misoprostol regimen (ie. vaginal or rapid interval) (n=22), allergy to analgesia regimen (n=14), <18 years of age (n=5), non-English speaking (n=4), prior participation in the trial (n=4), no access to cellular phone (n=3). †Analysis included the two participants who did not take the study capsule as directed within their allocated groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by treatment group

| Demographics | Pregabalin (n=55) |

Placebo (n=52) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean (years) | 27.25±5.45 | 27.19±6.02 |

| Race * | ||

| White | 20 (36.4%) | 21 (40.4%) |

| Black | 4 (7.3%) | 3 (5.8%) |

| Asian | 34 (61.8%) | 27 (51.9%) |

| Native Hawaiian | 17 (30.9%) | 17 (32.7%) |

| Hispanic | 10 (18.2%) | 7 (13.5%) |

| Other | 4 (7.3%) | 3 (5.8%) |

| Multiracial | 23 (41.8%) | 21 (40.4%) |

| Education | ||

| Some high school | 0 (0%) | 3 (5.8%) |

| Graduated high school | 8 (14.5%) | 13 (25%) |

| Some college | 29 (52.7%) | 24 (46.2%) |

| Graduated college | 15 (27.3%) | 12 (23.1%) |

| Post-college degree | 3 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mental Health | ||

| Depression | 11 (20%) | 10 (19.2%) |

| Anxiety | 7 (12.7%) | 9 (17.3%) |

| Pregnancy history | ||

| First pregnancy | 16 (29.1%) | 16 (30.8%) |

| Prior surgical abortion | 22 (40%) | 18 (34.6%) |

| Prior medical abortion | 6 (10.9%) | 7 (13.5%) |

| Prior miscarriage | 13 (23.6%) | 11 (22.2%) |

| Parous | 33 (60%) | 29 (55.8%) |

| Prior vaginal delivery | 29 (52.7%) | 25 (48.1%) |

| Prior cesarean section | 5 (9.1%) | 7 (13.5%) |

| Gestational age | ||

| Mean (days) | 53.51±8.16 | 55.15±6.90 |

| Groups (days) | ||

| 41-49 | 19 (34.5%) | 14 (26.9%) |

| 50-56 | 14 (25.5%) | 19 (36.5%) |

| 57-63 | 15 (27.3%) | 12 (23.1%) |

| 64-70 | 7 (12.7%) | 7 (13.5%) |

Data are n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

Participants could select more than one race.

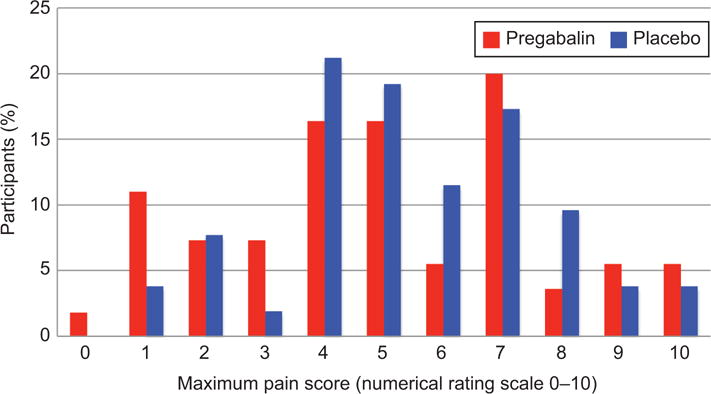

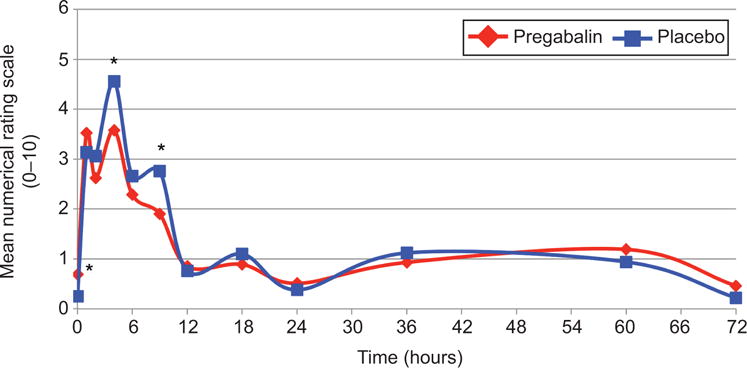

Participants in both groups had a mean anticipated maximum pain score of 6.8 ± 2.0; p=0.99. The primary outcome of experienced mean maximum pain scores were 5.0 ± 2.6 and 5.5 ± 2.2 in the pregabalin and placebo groups, respectively (p=0.32). The maximum pain score distribution was not statistically different between groups (p=0.64) (Figure 2). The secondary outcome of mean pain scores at specified time points are graphically represented in Figure 3. Immediately following the misoprostol, participants in the pregabalin group reported statistically higher pain levels, though both were less than one on the NRS (0.7 ± 1.3 versus 0.3 ± 0.9; p=0.04). Between hours two and six, maximum pain scores were lower in the pregabalin group (3.6 ± 2.5 versus 4.6 ± 2.3; p=0.04), with the same finding between hours six and twelve (1.9 ± 2.2 versus 2.8 ± 2.0; p=0.04), though this difference may not be clinically significant, particularly given evaluation of so many time points and the possibility of random variation. Maximum pain scores at other time points did not differ between groups. From hour 12 on, 62-80% of participants who received pregabalin reported no pain at each time point. For the placebo group, 46-82% reported no pain in the same period.

Figure 2.

Distribution of maximum pain scores by treatment group. The percentage of participants in each study group reporting each level of maximum pain. P=.64 using the Fisher exact test.

Figure 3.

Mean pain scores over time by treatment group. Mean pain scores at each time point over the study period, compared with t-tests. Because pain scores were compared at so many different time points, it is possible that some of the differences may be due to random variation. *P=.04 at time points 0, 4, and 9 hours.

Numbers of analgesic tablets were examined as a secondary outcome. Median ibuprofen use was one tablet in the pregabalin group (interquartile range [IQR] 0-4, range 0-8) and two tablets in the placebo group (IQR 1-3, range 0-8; p=0.34). Median oxycodone with acetaminophen use was 0 tablets in the pregabalin group (IQR 0-1, range 0-5) and 0.5 tablets in the placebo group (IQR 0-1, range 0-8; p=0.11).

Ibuprofen was taken prior to the study capsule by 30.9% (17/55) of the pregabalin group and 19.2% (10/52) of the placebo group (p=0.17). A narcotic was taken prior to the study capsule by 7.3% (4/55) of the pregabalin group and 3.8% (2/52) of the placebo group (p=0.68). Though participants were instructed to begin their pain management with ibuprofen, seven participants reported taking oxycodone before taking any ibuprofen (2/55 in the pregabalin group, 5/52 in the placebo group, p=0.21).

Pregabalin use was associated with not requiring any additional analgesics. Ibuprofen was needed by 72.7% (40/55) of the pregabalin group compared to 88.5% (46/52) of the placebo group (p=0.04). Those taking pregabalin were also less likely to use oxycodone with acetaminophen, 30.9% (17/55) compared to 50% (26/52) (p=0.04).

To further understand the potential analgesic-sparing effect of pregabalin, only analgesics taken after the study capsule were considered. Excluding medication taken before the study capsule, ibuprofen was used by 63.6% (35/55) of the pregabalin group versus 86.5% (45/52) of the placebo group (p<0.01). Narcotics were used by 29.1% (16/55) of the pregabalin group versus 50% (26/52) of the placebo group (p<0.03).

The list of experienced side effects in each group is shown in Table 2. Participants who received pregabalin reported significantly less constipation than placebo (p<0.02), but significantly more dizziness (p<0.001) during the abortion. When including only side effects reported after taking the study capsule, dizziness was more significant in the pregabalin group (p<0.001), as was sleepiness (p<0.04) and blurred vision (p<0.05), while no difference remained for constipation. There was no difference between groups for nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, or dry mouth.

Table 2.

Reported side effects by treatment group

| Side effects | Pregabalin (n=55) |

Placebo (n=52) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever experienced | |||

| Nausea | 43 (78.2%) | 42 (80.8%) | 0.74 |

| Vomiting | 28 (50.9%) | 30 (58.8%) | 0.41 |

| Sleepy | 47 (85.5%) | 39 (76.5%) | 0.24 |

| Dizzy | 45 (81.8%) | 26 (50%) | <0.01 |

| Headache | 28 (50.9%) | 17 (33.3%) | 0.07 |

| Blurred vision | 15 (27.3%) | 7 (13.7%) | 0.09 |

| Diarrhea | 28 (50.9%) | 29 (56.9%) | 0.54 |

| Constipation | 6 (10.9%) | 15 (29.4%) | <0.02 |

| Dry mouth | 22 (40%) | 25 (48.1%) | 0.40 |

| After study capsule | |||

| Nausea | 37 (67.3%) | 38 (73.1%) | 0.51 |

| Vomiting | 20 (36.4%) | 25 (49%) | 0.19 |

| Sleepy | 47 (85.5%) | 35 (68.6%) | <0.04 |

| Dizzy | 45 (81.8%) | 22 (42.3%) | <0.01 |

| Headache | 17 (30.9%) | 15 (29.4%) | 0.87 |

| Blurred vision | 15 (27.3%) | 6 (11.8%) | <0.05 |

| Diarrhea | 25 (45.5%) | 28 (54.9%) | 0.33 |

| Constipation | 5 (9.1%) | 11 (21.6%) | 0.07 |

| Dry mouth | 21 (38.2%) | 21 (40.4%) | 0.82 |

Data are n (%).

Satisfaction scores with the abortion process and analgesia are shown in Table 3. In the pregabalin group, 40.7% were very satisfied with the abortion process, compared with 21.6% in the placebo group (p=0.03). Satisfaction with analgesia was also higher in the pregabalin group, with 47.2% very satisfied with their pain control compared to 21.6% in the placebo group (p=0.006).

Table 3.

Satisfaction with abortion and analgesia by treatment group

| Likert scale 1-5 | Pregabalin | Placebo | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abortion satisfaction | (n=54) | (n=51) | 0.18 |

| Very dissatisfied | 1 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Dissatisfied | 1 (1.9%) | 2 (3.9%) | |

| Neutral | 12 (22.2%) | 18 (35.3%) | |

| Satisfied | 18 (33.3%) | 20 (39.2%) | |

| Very satisfied | 22 (40.7%) | 11 (21.6%) | <0.01* |

| Analgesia satisfaction | (n=53) | (n=51) | <0.01 |

| Very dissatisfied | 2 (3.8%) | 3 (5.9%) | |

| Dissatisfied | 3 (5.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Neutral | 12 (22.6%) | 13 (25.5%) | |

| Satisfied | 11 (20.8%) | 24 (47.1%) | |

| Very satisfied | 25 (47.2%) | 11 (21.6%) | <0.01* |

Data are n (%).

P-values refer to overall test by Chi-square.

P-value refers to “very satisfied” compared to all other responses.

DISCUSSION

We did not find a difference between groups in our primary outcome (mean maximum pain score), though pregabalin was associated with higher satisfaction and a greater likelihood of not requiring additional analgesics, at the expense of more reported side effects. Less than one-third of pregabalin users took a narcotic, compared to half of the placebo group. This is in contrast to previous reports of narcotic use in up to 75% of medication abortion patients.6 Given the potential for substance use disorders and side effects of narcotics, decreasing its use could have substantial public health benefit. This trial also provides evidence that if narcotics are prescribed to patients, a small number of pills should be prescribed, since the interquartile range of the placebo group was 0-1 tablets.

Maximum pain scores were lower than expected, with a mean maximum of 5.5 in the placebo group compared to six to eight in previous research.2–5 Pain duration was also shorter than expected, with over half of participants in both groups being pain free by 12 hours after misoprostol, in contrast to a previous study using the same regimen where 60% of participants reported pain lasting five or more days.2 One potential reason for lower reported pain scores is our use of a real time and short interval data collection tool. This allowed for immediate recording of pain scores, decreasing errors associated with retrospective report and recall bias. Prior studies have measured pain via retrospective maximum pain score, daily diary cards, and scores at time of analgesia use. Compared with those studies, our study has comparable prior abortion rates and gestational ages. Our population included a slightly lower proportion of primigravid women (30% versus 40-50%), though the proportion of nulliparous women was similar (42% versus 45-65%).2–5

Side effects were common in both groups, particularly gastrointestinal, which are commonly experienced in early pregnancy as well as with misoprostol. Over 80% of women in the placebo group reported nausea at least once, almost 60% vomited, and over 50% had diarrhea. These rates were lower in the pregabalin group, but not significantly. Pregabalin was associated with higher rates of sleepiness, dizziness, and blurred vision, which are known side effects.7 Despite the increase in some side effects, the pregabalin group had higher satisfaction with the abortion and pain control. This difference cannot be attributed to inadequate blinding, as equal numbers of participants in each group believed they received pregabalin (59%).

Strengths of this study include the randomized, double-blind controlled trial design and high follow-up with 93.6% of participants completing all six surveys and only 2.7% loss to follow-up. Our combination of text message prompt and online survey data collection tool may have contributed to this success. The prompt via text allowed participants immediate access to the survey, while protecting privacy by redirecting them to a survey without identifiers. Only three women (1.2% of those assessed for eligibility) were excluded due to lack of cellular phone.

One limitation is that we only included the buccal route of misoprostol. Other routes of misoprostol administration (oral, vaginal, sublingual) have shown differing side effect profiles and have different timing options for administration.9 This single regimen may limit generalizability to other modes of misoprostol administration, though the mechanism of action for pregabalin would not change. Another limitation is that all pain medications were dispensed, not prescribed, which may have influenced medication use. However, by eliminating the barrier of payment for prescriptions, it is likely that our finding is higher than real-world usage.

Pain that occurs over a period of time, as with medication abortion, is difficult to quantify with a single pain scale, and is subjective by nature. We chose to use multiple data points and real-time assessments to improve validity and mitigate recall bias. Even though over 80% of responses were submitted within two hours of the requested time, another limitation is the comparison of retrospectively recalled and real-time data, which may not be equivalent. We did find significant differences in analgesic usage and satisfaction, raising the possibility that type II error affected our primary outcome.

When studying pain, it may be that a maximum pain score is not the most important outcome. A peak value at a moment in time may not truly represent a longitudinal experience or reflect patients’ satisfaction with their care. While peak pain scores were not decreased with pregabalin, its association with increased satisfaction and decreased need for NSAIDs and narcotics along with its ease of administration make it a worthwhile adjunct in medication abortion care.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure

Dr. Soon receives research support from Contramed Pharmaceuticals, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, Mithra Pharmaceuticals, and Gynuity Health Projects. Dr. Tschann receives research support from Contramed Pharmaceuticals, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, Mithra Pharmaceuticals, Gynuity Health Projects, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Kaneshiro receives research support from Contramed Pharmaceuticals, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, Mithra Pharmaceuticals, Gynuity Health Projects, and the National Institutes of Health. She is also a consultant for UpToDate. All of these sources of outside research support did not play any role in this project’s study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing of the report, or decision to submit the report for publication.

Supported by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund, Grant Award Number SFPRF15-12.

Footnotes

The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Presented at the North American Forum on Family Planning, October 14-16, 2017, Atlanta, Georgia.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02782169.

References

- 1.Jones RK, Jerman J. Abortion incidence and service availability in the United States, 2014. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49 doi: 10.1363/psrh.12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Louie KS, Dean G, Porsch L, Lichtenberg ES, Ali R, Arnesen M. Prophylactic compared with therapeutic ibuprofen analgesia in first-trimester medical abortion: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:558–64. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31829d5a33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamoda H, Ashok PW, Flett GM, Templeton A. A randomised controlled trial of mifepristone in combination with misoprostol administered sublingually or vaginally for medical abortion up to 13 weeks of gestation. BJOG. 2005;112:1102–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livshits A, Machtinger R, David LB, Spira M, Moshe-Zahav A, Seidman DS. Ibuprofen and paracetamol for pain relief during medical abortion: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1877–80. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamoda H, Ashok PW, Dow J, Flett GM, Templeton A. A pilot study of mifepristone in combination with sublingual or vaginal misoprostol for medical termination of pregnancy up to 63 days gestation. Contraception. 2003;68:335–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penney G. Treatment of pain during medical abortion. Contraception. 2006;74:45–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toth C. Pregabalin: latest safety evidence and clinical implications for the management of neuropathic pain. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014;5:38–56. doi: 10.1177/2042098613505614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao Z, Shen C, Zhong Y. Perioperative pregabalin for acute pain after gynecological surgery: a meta-analysis. Clin Ther. 2015;37:1128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiala C, Cameron S, Bombas T, Parachini M, Saya L, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Pain during medical abortion, the impact of the regimen: a neglected issue? A review Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2014;19:404–19. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2014.950730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishriky BM, Waldron NH, Habib AS. Impact of pregabalin on acute and persistent postoperative pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2014;114:10–31. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong W, Wallace MS. Determination of the effective dose of pregabalin on human experimental pain using the sequential up-down method. J Pain. 2014;15:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todd KH, Funk KG, Funk JP, Bonacci R. Clinical significance of reported changes in pain severity. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:485–9. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bijur PE, Latimer CT, Gallagher EJ. Validation of a verbally administered numerical rating scale of acute pain for use in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:390–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]