Abstract

Background

Perturbations to embryonic hemodynamics are known to adversely affect cardiovascular development. Vitelline vein ligation (VVL) is a model of reduced placental blood flow used to induce cardiac defects in early chick embryo development. The effect of these hemodynamic interventions on maturing elastic arteries is largely unknown. We hypothesize that hemodynamic changes impact maturation of the dorsal aorta (DA).

Results

We examined the effects of VVL on hemodynamic properties well into the maturation process and the corresponding changes in aortic dimensions, wall composition, and gene expression. In chick embryos, we found that DA blood velocity was reduced immediately post-surgery at Hamburger-Hamilton stage (HH) 18 and later at HH36, but not in the interim. Throughout this period, DA diameter adapted to maintain a constant shear stress. At HH36, we found that VVL DAs showed a substantial decrease in elastin and modest increase in collagen protein content. In VVL DAs, upregulation of elastic fiber related genes followed the downregulation of flow-dependent genes. Together, these suggest the existence of a compensatory mechanism in response to shear induced delays in maturation.

Conclusions

The DA's response to hemodynamic perturbations invokes coupled mechanisms for shear regulation and matrix maturation, potentially impacting the course of vascular development.

Keywords: hemodynamics, shear stress, dorsal aorta, elastin

Introduction

Hemodynamic forces have long been identified as a driving mechanism in cardiovascular development. Altered loading conditions in the chicken embryo have been used to recreate congenital heart defects (CHD) found in humans, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome, double outlet right ventricle, and persistent truncus arteriosus (Sedmera et al. 1999). Although 20% of CHDs are vascular abnormalities (Roger et al. 2012), the impact of hemodynamic changes on the developing vasculature is not well understood.

In the chick embryo, heart contractions and blood flow begin between Hamburger-Hamilton (HH) stages 10–12, which corresponds to approximately 1.5–2 days of incubation out of a 21 day incubation period, ending at HH46 (Hamburger & Hamilton 1951; Hogers et al. 1995). At this point, intraembryonic circulation flows through a pair of nascent endothelial vessels which then fuse to become a single dorsal aorta (DA) by HH15 (Sato 2013). This is followed by arterial maturation, which we define as the evolution of the vessel wall from a thin endothelium to a thick layered structure consisting of multiple cell types and extracellular matrix (ECM). In the DA, this begins with the recruitment and differentiation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) identified by markers, such as IE12 and smooth muscle alpha (SMα) actin, both observed as early as HHl7 (Hungerford et al. 1996). This process begins adjacent to the endothelium and progresses radially outward (DeRuiter et al. 1997). Early ECM expression of fibulin-1, fibrillin-2, and fibronectin are also indicators of maturation and precede the development of an elastin and collagen rich matrix (Hungerford et al. 1996; Espinosa et al. 2018).

Elastin and collagen I expression are first detected in the aortic wall at about HH30 (Rosenquist et al. 1988; Bergwerff et al. 1998). Elastogenesis begins with the secretion of soluble tropoelastin in the conotruncus of the heart and progresses distally throughout the vascular tree (Rosenquist et al. 1988). Collagen fibers form concurrently, beginning as filamentous tufts adjacent to the cells (Karrer 1960). Electron micrographs of HH42 chick embryo DAs show both elastic and collagen fibers arranged in a lamellar pattern (Levene 1961). This compositional and structural arrangement imparts passive mechanical properties crucial to the maturing aorta in its hemodynamically demanding environment (Wagenseil & Mecham 2009).

It is well known that arteries adapt their lumen diameters to regulate wall shear stress (Zarins et al. 1987), especially in developmental processes, such as aortic arch patterning (Lindsey et al. 2015). Yet, few have investigated how hemodynamic perturbations affect vascular maturation. In HH27 embryos with increased arterial load, Lucitti et al. (2006; 2005) reported overexpression of collagen III and procollagen I, resulting in increased DA stiffness. Further investigation beyond the early detection of ECM markers is necessary to more thoroughly understand hemodynamic effects on arterial maturation.

In this paper, we use vitelline vein ligation (VVL) to study shear related effects on DA maturation from initial ECM deposition to fully formed layers in chick embryos. Although this intervention is performed on chick embryos, it serves as a model of reduced placental flow in mammals. VVL results in malformations of the ventricular septum, pharyngeal aortic arches, and heart valves (Hogers et al. 1997). We hypothesize that hemodynamically induced defects are not limited to the heart, but also include alterations to the composition and structure of the DA. To this end, we measure DA blood velocity in control and ligated embryos through HH36. DAs from both groups are examined at various points in the maturation process to measure their dimensions, ECM composition and structure, and gene expression. We found that VVL resulted in decreased elastin and increased collagen protein content in the DA wall at HH36. In situ hybridization (ISH) showed increased elastin gene expression along with downregulation of flow-dependent genes, suggesting that the SMCs compensate for this shear induced change in wall composition. This work elucidates the role of hemodynamics on arterial maturation, thus providing significant insights for both developmental biology and regenerative medicine.

Results

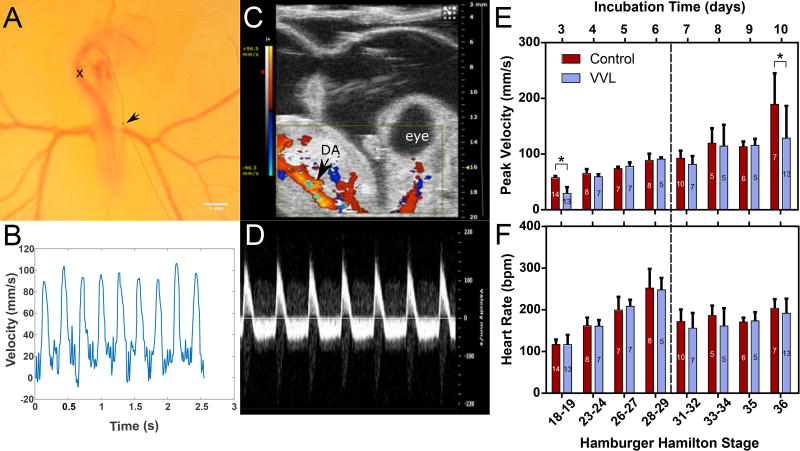

VVL Causes Blood Flow Reductions

Due to limitations to embryo access and changes in size, velocity measurements required the use of two different systems. DA blood velocity and heart rate were measured in young chick embryos (HH18-29) with a pulsed Doppler system at the level of the sinus venosus, marked with an×in Figure lA. A representative velocity trace from an HH27 embryo taken with this system is shown in Figure lB. Figures lC and lD show an HH36 embryo in Color Doppler and its corresponding velocity signal, respectively. Color Doppler video of the embryo in Figure lC can be found in the supplemental material. A comparison between both measurement methods at HH28-29 yields no significant difference (data not shown), showing that the change in methodology did not obfuscate the data.

Figure 1.

Blood flow measurements in the chick embryo DA. (A) HH18 embryo with right vitelline vein ligated (arrow). Peak blood velocity in DA measured at location marked by x. (B) Example flow velocity trace measured by Doppler flowmeter in younger embryos. (C) Ultrasound image of HH36 embryo with color Doppler identifying the DA. Color Doppler video corresponding to the embryo shown here can be found in the supplemental material. (D) Ultrasound pulse-wave Doppler mode measures blood velocity in older embryos. (E) Peak DA velocity decreases immediately after surgery (HH18-19) and again at HH36 (*=p≤0.05). (F) Heart rate is not impacted by intervention, but is affected by change in mode of measurement. For (E) and (F), the numbers within each bar represent the number of embryos and the dashed line indicates the change in measurement system.

The peak blood velocity through the DA of ligated embryos was significantly decreased immediately after surgery (HH18) and at HH36, by 49% and 32% respectively (Figure lE). At HH23-35, there were no differences between the peak blood velocity of VVL and control embryos. Although VVL did not appear to affect heart rate, as compared to controls, Figure lF shows a marked decrease in heart rate for all embryos when measured with ultrasound. This may be due to longer exposure and decreased temperature during ultrasound measurements. Correlations between heart rate and velocity were weak for all time points (data not shown).

Taken together, these results show a greater complexity in the hemodynamic response to VVL than previously reported (Stekelenburg-de Vos et al. 2003; Rugonyi et al. 2008), with decreased flow at both HH18 and HH36.

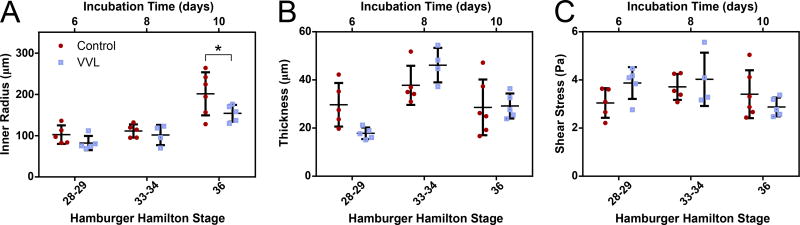

The Embryonic Aorta Adapts to its Hemodynamic Environment

As the embryos grew, the DA inner radius increased for both control and VVL embryos (Figure 2A). There was an observed 23% reduction in the radii of DAs from hemodynamically perturbed embryos at HH36 compared to controls. Although circumferential growth was observed in both groups, the thickness of the DA wall fluctuated around 30 µm throughout the developmental period studied here (Figure 2B). Despite these changes, shear stress was relatively constant over time and between experimental groups (Figure 2C). Since shear stress depends on both flow velocity and vessel radius (see Equation 2), these results suggest the existence of a homeostatic shear stress during early aortic maturation.

Figure 2.

Shear stress is maintained as the DA matures. In all embryos, DA inner radius (A) increases over time, but wall thickness (B) remains constant. At HH36, VVL embryos show a reduced luminal radius relative to controls (*=p≤0.05), corresponding to the decrease in flow at that time. Geometric adaptations may be used to regulate shear stress (C). Shear stress does not change between groups or throughout the period of time studied.

VVL Affects ECM Protein Alignment and Accumulation

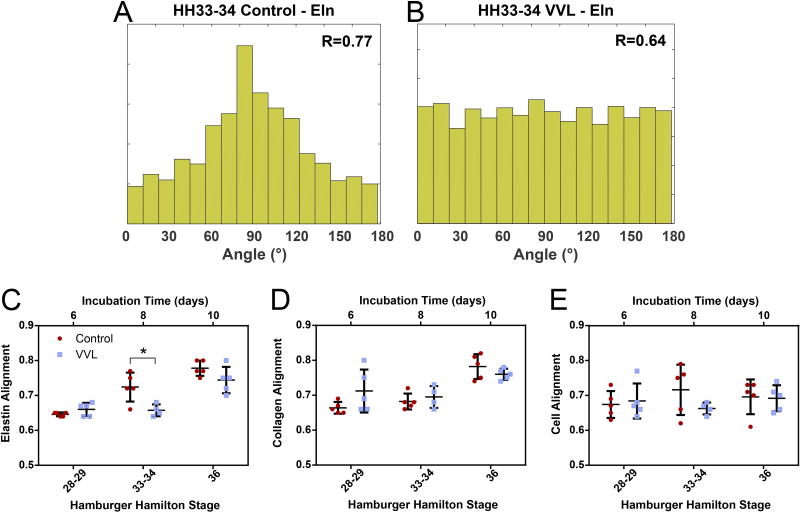

Relatively few ECM fibers were found in the DA of either control or VVL embryos at HH28-29. The fibers that were present had a fairly even distribution of orientations. By HH36, the number of fibers had substantially increased. They were found to be primarily aligned in the circumferential direction, defined as 90°. Representative histograms of a control (Figure 3A) and VVL (Figure 3B) DA at HH33-34 illustrate the reduction in elastic fiber alignment within the VVL group. As shown in Figure 3C, elastic fiber alignment for both groups increased over time, despite an apparent lag in VVL embryos. Collagen fibers similarly became increasingly aligned over time, but showed no differences between groups (Figure 3D). Cell alignment did not change over time (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

ECM fibers align circumferentially (90°). (A-B) Representative histograms of elastic fiber alignment are used to calculate a resultant vector (R), where R=1 indicates complete alignment. At HH33-34, elastic fiber alignment is reduced in a VVL DA (B) compared to a stage-matched control vessel (A). Elastin (C) and collagen (D) fibers are increasingly aligned over time, while cells (E) do not reorient. *=p≤0.05.

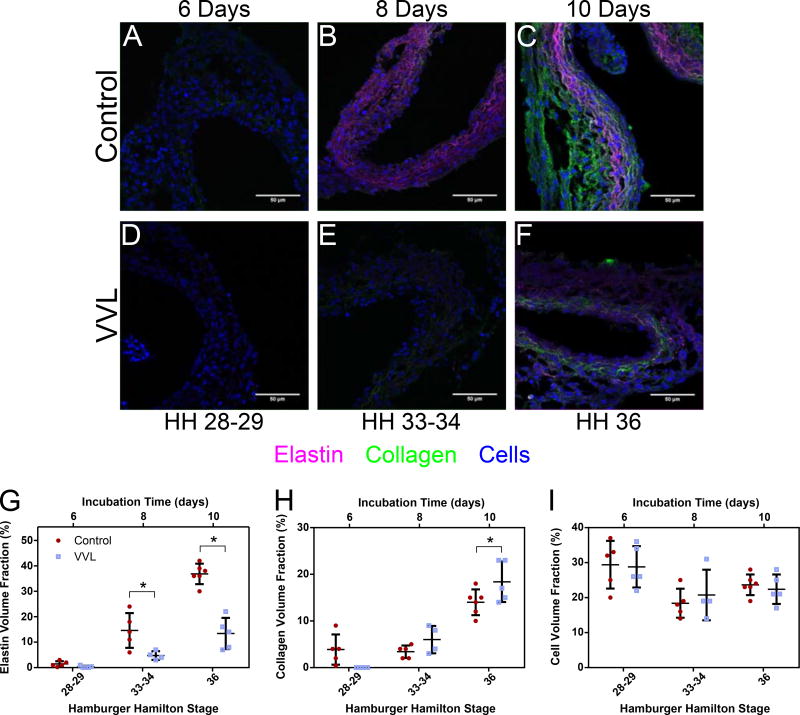

Representative confocal micrographs of control (Figure 4A-C) and VVL (Figure 4D-F) DA walls show a steady increase in ECM protein volume fraction over time. Quantification revealed differences between groups. Elastin content in DAs from ligated embryos showed a 67% and 64% decrease compared to controls at HH33 and HH36, respectively. Conversely, at HH36, VVL collagen content increased by 31% compared to controls. Cells made up about a quarter of the DA wall composition regardless of time or group.

Figure 4.

ECM and cellular makeup of the developing DA. (A-F) Representative confocal micrographs showing fluorescent staining of elastin (purple), collagen (green), and cells (blue) in arterial cross sections at varying time points. (G-I) Quantification of constituent volume fractions from confocal z-stack experiments. *=p≤0.05. DAs from ligated embryos have decreased elastin content (G), but also increased collagen (H). Cellular composition (I) is unchanged.

Together, these results confirm that both ECM alignment and content increase in the DA wall as maturation progresses, but the latter is more broadly impacted by VVL. These data support our hypothesis that hemodynamic intervention alters aortic maturation. It is also noteworthy that cell alignment and volume fraction are unchanged throughout this developmental process and unaffected by hemodynamic perturbation.

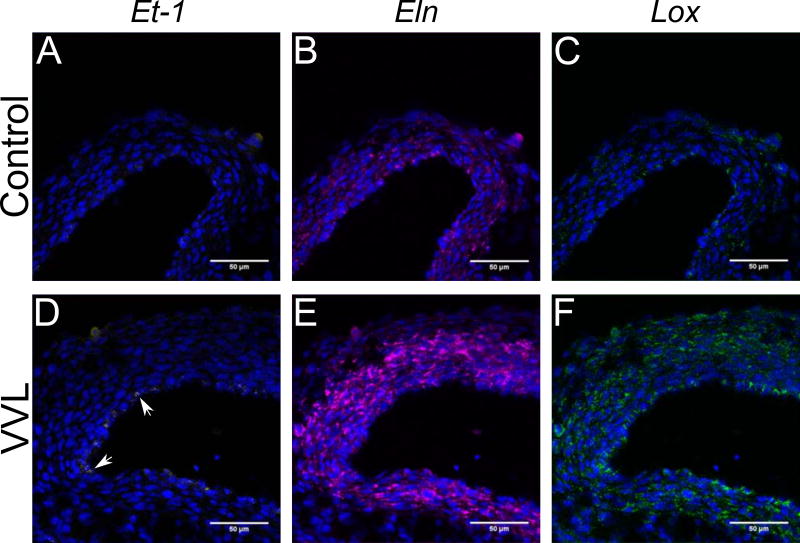

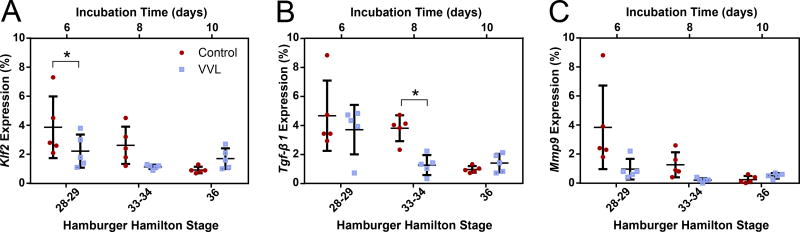

Gene Expression is Modulated by Wall Composition

VVL changed ECM protein amounts and may be linked to signaling due to altered shear stress on endothelial cells. Changes in flow and matrix related gene expression were investigated using two sets of three-plex ISH assays. As endothelin-1 (Et-1) has been linked to elastin (Eln) and lysyl oxidase (Lox) expression and Lox is necessary to crosslink soluble tropoelastin (Wachi et al. 2001), we examined expression levels of Et- 1, Eln, and Lox in the first set of experiments. We expect Et-1 expression to be limited to endothelial cells (Groenendijk et al. 2005), while Eln and Lox are more broadly expressed transmurally (Wagenseil & Mecham 2009). Sample confocal images show gene expression distribution of Et-1, Eln, and Lox across the DA wall at HH36 for both groups (Figure 5). Some VVL DAs showed punctate markers of Et-1 expression, such as in Figure 5D, but this was not consistently observed. The Eln (Figure 5E) and Lox (Figure 5F) upregulation shown here is highly representative of all samples.

Figure 5.

ISH showing Et-1 (yellow), Eln (purple), and Lox (green) expression in control (A-C) and VVL embryos (D-F) at HH36. Cell nuclei (blue) are stained with DAPI. Et-1 expression at the intimal layer (white arrows) is increased in select VVL DAs (D) as compared to controls (A), but is not consistently observed. Both Eln and Lox expression are substantially higher in VVL vessels (E and F) compared to controls (B and C).

Gene expression for Et-1, Eln, and Lox were quantified at HH28-29, 33-34, and 36 (Figure 6). Although no significant differences were seen in Et-1 expression (Figure 6A), both Eln (Figure 6B) and Lox (Figure 6C) expression differed between control and VVL groups. Over time, Eln expression increased, but is significantly upregulated by a factor of 1.5 in VVL samples compared to controls at HH36. Between HH28 and HH34, Lox expression remains constant and is unaffected by ligation. Interestingly, Lox expression at HH36 is significantly downregulated by 73% in control DAs, while VVL DAs retain the previous expression levels.

Figure 6.

Quantification of gene expression in the DA wall of control and ligated embryos at HH28-29, 33-34, and 36. (A) Expression of Et-1 is low as it is limited to endothelial cells found at the luminal side of the DA. There is no statistical difference between groups. (B) Eln expression is initially comparable between groups, but is doubled in VVL DAs at HH36. (C) Lox expression is decreased in HH36 controls compared to earlier time points and age matched VVL samples. *=p≤0.05.

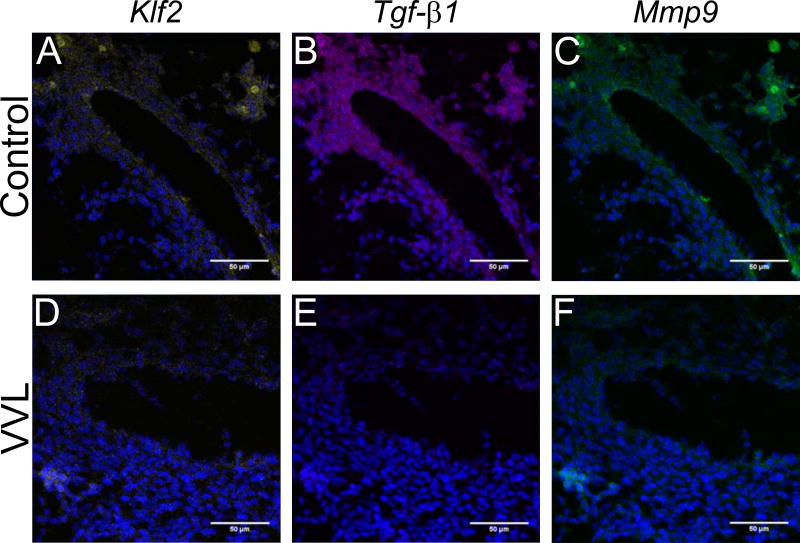

The second set of assays targeted lung Krüppel-like factor (Klf2), transforming growth factor-beta 1 (Tgf-β1), and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (Mmp9), as these have all been shown to be shear responsive and impact ECM remodeling (Kuo et al. 1997; Chatzizisis et al. 2007; Tronc et al. 2000; Galis et al. 2002). We anticipate that all mural cells express these genes (Wu et al. 2008; Antonelli-Orlidge et al. 1989; Tronc et al. 2000). Figure 7 shows representative micrographs with reduced expression for all three genes in VVL DAs at HH28-29. Downregulations in the VVL group, ranging from 21% to 84%, persist through HH34 (Figure 8). Although not all comparisons are statistically significant, the differences in average expression between control and VVL throughout the period studied are compelling.

Figure 7.

Representative ISH showing decreased expression of Klf2 (yellow), Tgf-β1 (purple), and Mmp9 (green) in VVL embryos (D-F) as compared to controls (A-C) at HH28-29. Cell nuclei (blue) are stained with DAPI.

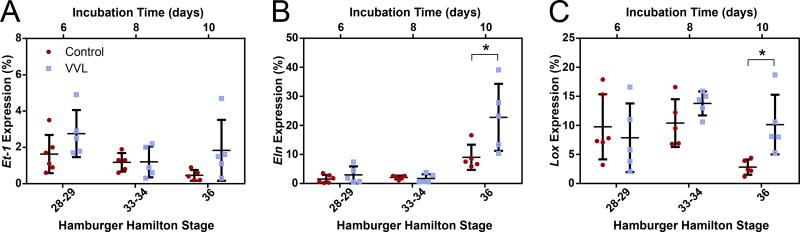

Figure 8.

Quantification of Klf2, Tgf-β1, and Mmp9 expression in the DA wall of control and ligated embryos at HH28-29, 33-34, and 36. (A) Expression of Klf2 is approximately halved in VVL DAs through HH34. Tgf-β1 (B) and Mmp9 (C) expression are similarly reduced in the VVL group until HH36. Differences in gene expression precede or coincide with VVL-induced changes in matrix protein composition. *=p≤0.05.

In summary, downregulation of Klf2, Tgf-β1, and Mmp9 precedes upregulation of Eln and Lox in VVL DAs at HH36. This further supports a link between shear stresses applied on the endothelium and the maturation process governed by medial layer SMCs.

Discussion

Investigations linking hemodynamic perturbations and cardiovascular defects in the chick embryo have been largely limited to the heart during early development (≤HH24) (Midgett & Rugonyi 2014). In the present study, we found that VVL not only had a transient hemodynamic effect, but also caused a later reduction in blood flow well into the aortic maturation process (HH36) (Figure lE). Maturation of the DA was altered in VVL embryos as evidenced by decreased elastin and increased collagen protein content (Figure 4G-H). Gene expression assays suggest that SMCs adapt to their surrounding ECM by overexpressing RNA (Figure 6) to overcome protein deficiencies triggered by flow dependent signaling pathways (Figure 8). This implies that the aortic maturation process includes a compensatory response to hemodynamic changes and subsequent ECM deficiencies.

Effects of Ligation on the Maturing DA

Our experiments show that VVL performed at HH18 caused an immediate decrease in blood velocity in the DA, followed by normalization of flow within a 24-hour period (Figure lE), agreeing with previously reported data (Stekelenburg-de Vos et al. 2003; Rugonyi et al. 2008). This early response is likely governed by capillary remodeling and DA vasoconstriction, as evidenced by Et-1 upregulation (Stekelenburg-de Vos et al. 2003; Groenendijk et al. 2005). Control and VVL embryos continued to show comparable DA blood velocities until a significant reduction in flow was measured in the VVL group at HH36. Large variation in the data may be partially attributed to typical experimental noise, but also suggests that not all embryos experienced this late decrease in flow. This is supported by our variable Et-1 expression data (Figure 6A) and reports of only a 65% incidence of cardiac defects in the VVL model (Hogers et al. 1997; Broekhuizen et al. 1999).

Hemodynamic measurements in older chick embryos are technically challenging and uncommon, with the majority of VVL flow data ending at HH24 (Stekelenburg-de Vos et al. 2003; Groenendijk et al. 2008; Rugonyi et al. 2008). With the exception of our current study, Broekhuizen et al. (1993; 1999) are the only others to measure DA blood velocity past this stage. In contrast to our results, they report an increase in flow at HH34. Although the reason for this discrepancy remains unknown, we suggest that differences in equipment capabilities may play a role. For example, the probe signal direction is fixed in the pulsed Doppler flowmeter, making it difficult to obtain and determine an appropriate Doppler angle with respect to a submerged embryo's DA. With ultrasound, increased penetration depth, visual confirmation with color Doppler, and an adjustable beam angle all lend additional confidence to our measurements. Although other groups have begun to utilize ultrasound in chick embryo studies, these have focused on cardiac imaging (Bharadwaj et al. 2012; Midgett et al. 2017). To our knowledge, we are the first to incorporate ultrasound Doppler to interrogate hemodynamic parameters in the DA at these later stages of chick embryo development.

Changes in the expression of Et-1 and Klf2 in the VVL model have been investigated here (Figure 6A and Figure 8A) and by others. While several reports of Et-1 upregulation in VVL embryos at earlier stages exist (Groenendijk et al. 2007), we did not consistently observe this in older VVL embryos (after HH28). Difficulties in the detection of Et-1 expression, which is spatially limited to the endothelium, may be due to a reduction in expression over time, such as that observed in the outflow tract (Groenendijk et al. 2004). Conversely, downregulation in our Klf2 expression data from ligated embryos is consistent with previous reports in younger embryos within hours of VVL (Groenendijk et al. 2005). Although the role of Klf2 in cardiac defects is well documented, we examined its effect on arterial maturation. In Klf2 knockout mice at embryonic day (E) 12.5, both SMα actin and ECM content are decreased in the DA and umbilical vessels, respectively (Kuo et al. 1997). This finding supports our results showing decreased elastin protein amounts in maturing DAs from the VVL group (Figure 4G).

To further establish a link between flow and DA maturation, we also investigated the effect of VVL on two additional genes: Tgf-β1 and Mmp9. Tgf-β1 expression has been shown to be proportional to shear stress in both cell culture (Ohno et al. 1995) and tissue-scale (Chatzizisis et al. 2007) measurements. The relationship between flow and Mmp9 expression is less clear. Models of low (Godin et al. 2000) and high (Tronc et al. 2000) shear stress have both resulted in Mmp9 upregulation. Here, we observe downregulation of both Tgf-β1 and Mmp9 (Figure 8B and C). Given its role in elastic fiber formation (Kucich et al. 2002; Espinosa et al. 2018), a VVL-induced reduction in Tgf-β1 is likely to produce the elastin protein deficiencies observed here (Figure 4G). Meanwhile, downregulation of Mmp9 is known to result in additional collagen accumulation (Galis et al. 2002) and may account for the increased collagen content observed in VVL DAs (Figure 4H). Although ECM quantity is affected by perturbed hemodynamics, fiber orientation appears largely unaffected (Figure 3).

Compensatory Mechanisms After VVL

Vascular adaptations to changes in the loading environment occur in a variety of ways. For example, within 30 minutes of VVL, remodeling of the capillary plexus results in a substantial recovery of DA blood flow (Stekelenburg-de Vos et al. 2003). Another widely observed mechanism in vessels ranging from capillaries (Thoma 1893) to arteries (Zarins et al. 1987) is the alteration of lumen diameter to optimize shear stress. Throughout the maturation period studied here, we found that the vessel maintained a shear stress of about 3 Pa regardless of hemodynamic conditions (Figure 2C). Maintenance of a homeostatic shear stress may be an important mechanism to prevent the formation of defects, such as those observed in the hearts of VVL embryos in regions of significant change in shear (Hogers et al. 1997).

VVL induced changes to the composition of the DA wall may also trigger other adaptive processes. Previous in vitro and in vivo models suggest that SMCs respond to their surrounding ECM. For example, the elastic modulus and phenotype of murine Eln-/- SMCs can be restored to wildtype conditions with elastin treatments in the culture media (Espinosa et al. 2014). In the case of elastin haploinsufficiency, SMCs alter elastic fiber distribution to maintain the same load per lamellar unit found in the wildtype mice (Wagenseil et al. 2005). Given these elastin-mediated responses and the large changes in elastin content of VVL DAs presented here, we posit that the formation of new elastic fibers may be affected by the previously formed ECM. Increased Eln gene expression in HH36 VVL DAs (Figure 6E) may be a compensatory mechanism to recover from lagging elastin synthesis (Figure 4G) and establish normal aortic wall conditions. At HH36, Lox expression appears to drop in controls compared to the previously established baseline, but is sustained in VVL DAs. This suggests that a greater level of Lox crosslinking activity must be maintained to accommodate increases in Eln expression.

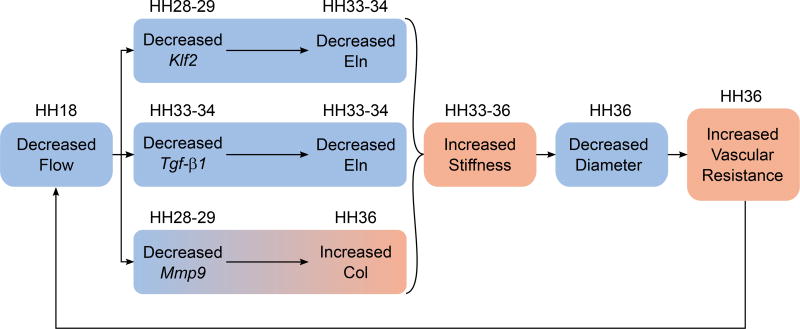

Together, these adaptive mechanisms may feed into a positive feedback loop responsible for recurring hemodynamic perturbations several days post-surgery, as observed in HH36 ligated embryos (Figure 9). We speculate that the immediate reduction in flow and shear stress due to VVL at HH18 elicits shear responsive signaling pathways that collectively assist in shear stress regulation, but also impact arterial maturation. It is important to keep in mind that these effects are not immediately apparent since elastin and collagen syntheses are not detected until HH28. Downregulation of Klf2, Tgf-β1, and Mmp9 prior to or concurrent with ECM protein changes implies a causal relationship. Although SMCs may compensate for suboptimal ECM composition, their response may be delayed, as shown by late Eln and Lox upregulation (Figure 6B-C). These ECM changes are likely to result in a stiffer DA and also limit radial distension due to pressure, which is unaffected by ligation (Midgett & Rugonyi 2014). Since vascular resistance is inversely proportional to the fourth power of radius (Thurston 1976), we expect that the reduction in DA radius at HH36 (Figure 2A) would approximately triple the aortic resistance to flow. Both increased arterial stiffness and vascular resistance are associated with increased left ventricular afterload (Nichols et al. 2008; Lucitti et al. 2006), which in turn reduces both stroke volume and cardiac output (MacGregor et al. 1974). By this process, the adaptive response to a decrease in DA flow succeeds in temporarily regulating shear stress, but at the cost of long term arterial stiffening and further decreases in flow.

Figure 9.

Decreased flow due to VVL reduces the expression of flow-dependent, matrix-regulating genes. These correspond to experimentally observed changes in elastin and collagen protein content, resulting in arterial stiffening. Downstream effects include reduced diameter, increased vascular resistance, and a further decrease in flow. HH stage for each effect is shown above. Blue and orange indicate a decrease and increase, respectively.

Limitations and Future Work

Our study investigated the hemodynamic impact on DA maturation in embryos from HH18 to HH36. Throughout this developmental period, the chick embryo becomes substantially larger, more opaque, sub-merged within the yolk, and obscured by the allantois. These developmental changes made measurements with the traditional Doppler flowmeter unreliable and motivated our transition to ultrasound. Ideally, all measurements would be performed with the same system. Although ultrasound may be used to image younger embryos, the maximum resolution for Doppler measurements may be inadequate for small DAs in early development. Additionally, the probe's large footprint renders these measurements terminal and would vastly increase the number of required embryos. Another alternative would be to employ an ex ovo culturing technique to provide greater probe access, but survival rate tends to decrease and it is unclear if this change would affect our measurements.

Although chick embryos are ideal for physical manipulations, many species-dependent assays have not been developed or optimized for chickens. This limited the immunofluorescent options for imaging ECM related proteins. Although this can be partially circumvented by ISH, this requires the design of new probes, adding to experimental time and expense. ISH protocols used here are restricted to three probes at a time and disallowed measurements of collagen expression.

Together, physical interventions and ISH assays can also be used to investigate how shear responsive genes are affected by high shear stress conditions. Increased DA blood flow can be accomplished through outflow tract banding, which is also frequently used to induce heart defects (Midgett & Rugonyi 2014). Flow-dependent changes to gene expression in an OTB model are likely to also impact matrix protein development. These data would be complementary to the results presented here and could provide further evidence linking shear stress to arterial maturation.

Our work establishes an important link between hemodynamics and vascular development that merits further investigation. Given the prevalence of ultrasound screening in prenatal evaluations, these insights may prove to be instrumental for the non-invasive diagnosis of CHDs. Further observations from both clinical and research settings may continue to shed light on the role that hemodynamics plays in vascular development, disease, and regeneration.

Experimental Procedures

Embryo Culture and Ligation

Fertilized white Leghorn chicken eggs were incubated blunt side down at 38°C for 3 days to reach HH18. All embryos were exposed through a small window in the shell above the air sac. Embryo stage was confirmed through visual inspection by comparison to characteristics specified for HH18 by Hamburger and Hamilton (1951). Embryos in the experimental group had the right vitelline vein ligated using a 9-0 nylon monofilament suture. Control embryos were resealed with transparent tape without ligation. In between flow measurements, all eggs were sealed and incubated.

Dorsal Aorta Blood Velocimetry

A 20 MHz pulsed Doppler flowmeter (545C-4, University of Iowa Bioengineering) with a 45° angled microvessel needle transducer (Model N, Iowa Doppler Products) was used to measure flow through the DA in embryos at HH18-29. HH18 ligated embryos were measured immediately after surgery. Flowmeter data was recorded using a data acquisition system (MPS 150, Biopac) and later filtered and analyzed using a custom Matlab script. After HH29, blood flow was measured using ultrasound (VEVO 2100, VisualSonics) due to the increase in size and vascular complexity in older embryos. Color Doppler was used to identify the dorsal aorta and pulse wave Doppler mode was used to measure flow. Approximately 25% of the measurements were repeated from a previously used embryo. This was only the case for flowmeter measurements. Embryos examined with ultrasound were immediately discarded and not used for further measurements. In both experimental arrangements, aortic blood flow was measured along the centerline of the vessel at the level of the sinus venosus.

Fluorescent Staining

At HH28-29, HH33-34, and HH36, embryos were removed from the egg. During dissection, embryo limbs and feather-germs were examined to determine HH stage. These observations confirmed that ligation did not cause developmental delays in non-vascular systems. The DA was dissected and immersed in 0.61 µM Alexa Fluor 633 hydrazide (Life Technologies) for 2 hours to stain for elastin (Shen et al. 2012; Clifford et al. 2011). The tissue was then fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 6 hours, incubated in 30% sucrose overnight, and embedded in optical cutting temperature (OCT) medium. The vessels were sliced into 20 µm sections using a cryostat. Sections used in this study were obtained from within 200 µm of the proximal end of the samples. The sections were rinsed with 1X phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution and then incubated for 20 minutes in 5 µM CNA35 (provided by Magnus Höök, Texas A&M) labeled with Oregon Green 488 (Life Technologies) for collagen I and III staining (Krahn et al. 2006). Cells were labeled with 10 µM CellTracker Blue CMAC (C2110, Invitrogen) for 30 minutes, followed by a 1 minute incubation with DAPI (Sigma) in PBS. The sections were imaged using a 10x objective to view the entire DA ring and a 40x oil immersion objective to capture a Z-stack. All images were acquired on a Zeiss confocal microscope.

Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization

Gene expression of Et-1, Eln, Lox, Klf2, Tgf-β1, and Mmp9 in DAs were examined at HH28-29, HH33-34, and HH36. RNAscope probes of these six genes were designed to detect the corresponding RNA in chicken tissue. These probes were designed and purchased from Advanced Cell Diagnostics. The RNAscope Fluorescent Multiplex Reagent Kit (320850, Advanced Cell Diagnostics) was used on 15 µm fixed frozen sections according to the manufacturer's instructions. Again, sections were limited to within 200 µm of the proximal end. Cell nuclei were labeled with DAPI. The 40x oil objective was used to image a representative area of the vessel wall. Confocal image acquisition settings were unchanged throughout the experiment.

Image Analysis

Cross-Sectional Dimensions

Inner and outer perimeters of fixed DA in 10x confocal images were traced and measured using ImageJ (NIH). Assuming the perimeter, P, is equivalent to the vessel's cross-sectional circumference when perfectly circular, the inner (i) and outer (o) radii are calculated as Ri,o = Pi,o/2π. Wall thickness was calculated as the difference between outer and inner radii. Distortion due to tissue fixation likely results in shrinkage. As all our samples were prepared the same way, these distortions are comparable among the groups and do not affect observed trends. These measurements were used in conjunction with previously acquired velocity data to determine wall shear stress. Since the Reynolds number is very low in the chick embryo (Kowalski et al. 2014), flow velocity profiles are relatively parabolic and the velocity distribution is approximated by

| (1) |

Where r is the radial distance from the centerline, vm is the maximum velocity, and Ri is the vessel inner radius. Average wall shear stress exerted by the oscillating flow is given by

| (2) |

where µ is viscosity. Embryonic avian blood viscosity has been measured to be about 1.7 cP (Al-Roubaie et al. 2011).

Wall Constituents

Regions of interest (ROIs) were defined by tracing the vessel walls with segmented lines in ImageJ. The lines were smoothed with the Spline Fit option and their thicknesses adjusted to encompass both the medial and intimal layers. ROIs were isolated and straightened using the Straighten tool.

The Directionality plugin was used to generate histograms showing the orientation of elastin, collagen, and cell components individually for each ROI. These data were input into the Circular Statistics toolbox developed for Matlab (Berens 2009) to calculate a mean direction and spread. The latter is known as the resultant vector length and indicates stronger alignment as it approaches 1.

Wall composition was determined by thresholding each channel to identify the pertinent structure as white and all other spaces as black. A custom Matlab script calculated a volume fraction for each constituent based off of the number of white pixels and the total number of pixels in the z stack experiment. A similar script was designed to quantify RNA expression as an area fraction from a single image.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance between control and VVL groups or between time points within each group was determined using two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc tests. Significance was defined as p≤0.05.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Video 1: Color Doppler of HH36 embryo. Red and blue signals represent flow towards and away from the probe, respectively. Dorsal aortic blood flow is seen on the left, while flow to the embryo’s head is seen on the right.

Bullet Points.

Vitelline vein ligation causes immediate and long-term decreases in dorsal aorta blood velocity.

Dorsal aortas from both control and ligated embryos modulate lumen size to regulate shear stress.

Elastin and collagen protein content are altered in the dorsal aorta of ligated embryos.

Elastin and lysyl oxidase mRNA upregulation compensates for reduced elastin protein.

Flow-dependent matrix-regulating gene downregulation in VVL embryos accounts for changes in developing matrix.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation CMMI 1662434 (JEW), the National Institutes of Health ROl NS070918 (LAT) and Washington University's Chancellor's Graduate Fellowship Program (MGE).

References

- Al-Roubaie S, Jahnsen ED, Mohammed M, Henderson-Toth C, Jones EAV. Rheology of embryonic avian blood. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(6):H2473–H2481. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00475.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli-Orlidge A, Saunders KB, Smith SR, D'Amore PA. An activated form of transforming growth factor beta is produced by cocultures of endothelial cells and pericytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1989;86(12):4544–4548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berens P. CircStat: A MATLAB Toolbox for Circular Statistics. J Stat Softw. 2009;31(10):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bergwerff M, Gittenberger-De Groot AC, Deruiter MC, van Iperen L, Meijlink F, Poelmann RE. Patterns of paired-related homeobox genes PRXl and PRX2 suggest involvement in matrix modulation in the developing chick vascular system. Dev Dyn. 1998;213(1):59–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199809)213:1<59::AID-AJA6>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj KN, Spitz C, Shekhar A, Yalcin HC, Butcher JT. Computational fluid dynamics of developing avian outflow tract heart valves. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40(10):2212–2227. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekhuizen ML, Hogers B, DeRuiter MC, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Wladimiroff JW. Altered hemodynamics in chick embryos after extraembryonic venous obstruction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13(6) doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.13060437.x. 437-4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekhuizen ML, Mast F, Struijk PC, Van Der Bie W, Mulder PG, Gittenberger-De Groot AC, Wladimiroff JW. Hemodynamic parameters of stage 20 to stage 35 chick embryo. Pediatr Res. 1993;34(1):44–46. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199307000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzizisis YS, Coskun AU, Jonas M, Edelman ER, Feldman CL, Stone PH. Role of endothelial shear stress in the natural history of coronary atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling: molecular, cellular, and vascular behavior. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(25):2379–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PS, Ella SR, Stupica AJ, Nourian Z, Li M, Martinez-Lemus LA, Dora KA, Yang Y, Davis MJ, Pohl U, Meininger GA, Hill MA. Spatial distribution and mechanical function of elastin in resistance arteries: a role in bearing longitudinal stress. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(12):2889–96. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.236570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRuiter MC, Poelmann RE, VanMunsteren JC, Mironov V, Markwald RR, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Embryonic endothelial cells transdifferentiate into mesenchymal cells expressing smooth muscle actins in vivo and in vitro. Circ Res. 1997;80(4):444–451. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.4.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa MG, Gardner WS, Bennett L, Sather BA, Yanagisawa H, Wagenseil JE. The effects of elastic fiber protein insufficiency and treatment on the modulus of arterial smooth muscle cells. J Biomech Eng. 2014;136(2):021030.1–021030.7. doi: 10.1115/1.4026203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa MG, Staiculescu MC, Kim J, Marin E, Wagenseil JE. Elastic Fibers and Large Artery Mechanics in Animal Models of Development and Disease. J Biomech Eng. 2018;140(2):020803.1–020803.13. doi: 10.1115/1.4038704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galis ZS, Johnson C, Godin D, Magid R, Shipley JM, Senior RM, Ivan E. Targeted disruption of the matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene impairs smooth muscle cell migration and geometrical arterial remodeling. Circ Res. 2002;91(9):852–859. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000041036.86977.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin D, Ivan E, Johnson C, Magid R, Galis ZS. Remodeling of carotid artery is associated with increased expression of matrix metalloproteinases in mouse blood flow cessation model. Circulation. 2000;102(23):2861–2866. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.23.2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk BC, Van der Heiden K, Hierck BP, Poelmann RE. The role of shear stress on ET-1, KLF2, and NOS-3 expression in the developing cardiovascular system of chicken embryos in a venous ligation model. Physiology. 2007;22(6):380–389. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00023.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk BCW, Hierck BP, Gittenberger-De Groot AC, Poelmann RE. Development-related changes in the expression of shear stress responsive genes KLF-2, ET-1, and NOS-3 in the developing cardiovascular system of chicken embryos. Dev Dyn. 2004;230(1):57–68. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk BCW, Hierck BP, Vrolijk J, Baiker M, Pourquie MJBM, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Poelmann RE. Changes in shear stress-related gene expression after experimentally altered venous return in the chicken embryo. Circ Res. 2005;96(12):1291–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000171901.40952.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk BCW, Stekelenburg-De Vos S, Vennemann P, Wladimiroff JW, Nieuwstadt FTM, Lindken R, Westerweel J, Hierck BP, Ursem NTC, Poelmann RE. The Endothelin-1 Pathway and the Development of Cardiovascular Defects in the Haemodynamically Challenged Chicken Embryo. J Vasc Res. 2008;45:54–68. doi: 10.1159/000109077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburger V, Hamilton HL. A series of normal stages in the development of the chick embryo. J Morphol. 1951;88(1):49–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogers B, DeRuiter M, Baasten A, Gittenberger-de Groot A, Poelmann R. Intracardiac Blood Flow Patterns Related to the Yolk Sac Circulation of the Chick Embryo. Circ Res. 1995;76(5):871–877. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.5.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogers B, DeRuiter M, Gittenberger-de Groot A, Poelmann R. Unilateral Vitelline Vein Ligation Alters Intracardiac Blood Flow Patterns and Morphogenesis in the Chick Embryo. Circ Res. 1997;80(4):473–481. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.4.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford JE, Owens GK, Argraves WS, Little CD. Development of the aortic vessel wall as defined by vascular smooth muscle and extracellular matrix markers. Dev Biol. 1996;178(2):375–92. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karrer HE. Electron microscope study of developing chick embryo aorta. J Ultrastructure Research. 1960;4(3–4):420–454. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(60)80032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski WJ, Pekkan K, Tinney JP, Keller BB. Investigating developmental cardiovascular biomechanics and the origins of congenital heart defects. Front Physiol. 2014;5:408.1–408.16. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn KN, Bouten CV, van Tuijl S, van Zandvoort MA, Merkx M. Fluorescently labeled collagen binding proteins allow specific visualization of collagen in tissues and live cell culture. Anal Biochem. 2006;350(2):177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucich U, Rosenbloom JC, Abrams WR, Rosenbloom J. Transforming growth factor-β stabilizes elastin mRNA by a pathway requiring Smads, protein kinase C-δ, and p38. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26(2):183–188. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.2.4666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CT, Veselits ML, Barton KP, Lu MM, Clendenin C, Leiden JM. The LKLF transcription factor is required for normal tunica media formation and blood vessel stabilization during murine embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11(22):2996–3006. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levene CI. Collagen as a tensile component in the developing chick aorta. Br J Exp Pathol. 1961;42(1):89–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey SE, Menon PG, Kowalski WJ, Shekar A, Yalcin HC, Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Butcher JT, Pekkan K. Growth and hemodynamics after early embryonic aortic arch occlusion. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015;14(4):735–751. doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0633-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucitti JL, Tobita K, Keller BB. Arterial hemodynamics and mechanical properties after circulatory intervention in the chick embryo. J Exp Biol. 2005;208(Pt 10):1877–85. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor DC, Covell JW, Mahler F, Dilley RB, Ross J. Relations between afterload, stroke volume, and descending limb of Starlings curve. Am J Physiol. 1974;227(4):884–890. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.227.4.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgett M, López CS, David L, Maloyan A, Rugonyi S. Increased Hemodynamic Load in Early Embryonic Stages Alters Myofibril and Mitochondrial Organization in the Myocardium. Front Physiol. 2017;8:631.1–631.15. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgett M, Rugonyi S. Congenital heart malformations induced by hemodynamic altering surgical interventions. Front Physiol. 2014;5(1):287.1–287.18. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols WW, Denardo SJ, Wilkinson IB, McEniery CM, Cockcroft J, O’Rourke MF. Effects of arterial stiffness, pulse wave velocity, and wave reflections on the central aortic pressure waveform. J Clin Hypertens. 2008;10(4):295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.04746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno M, Cooke JP, Dzau VJ, Gibbons GH. Fluid shear stress induces endothelial transforming growth factor beta-1 transcription and production. Modulation by potassium channel blockade. J Clin Investig. 1995;95(3):1363–1369. doi: 10.1172/JCI117787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Soliman EZ, Sorlie PD, Sotoodehnia N, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist TH, McCoy JR, Waldo KL, Kirby ML. Origin and propagation of elastogenesis in the developing cardiovascular system. Anat Red. 1988;221(4):860–71. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092210411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugonyi S, Shaut C, Liu A, Thornburg K, Wang RK. Changes in wall motion and blood flow in the outflow tract of chick embryonic hearts observed with optical coherence tomography after outflow tract banding and vitelline-vein ligation. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53(18):5077–5091. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/18/015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y. Dorsal aorta formation: separate origins, lateral-to-medial migration, and remodeling. Dev Growth Differ. 2013;55(1):113–29. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmera D, Pexieder T, Rychterova V, Hu N, Clark EB. Remodeling of chick embryonic ventricular myoarchitecture under experimentally changed loading conditions. Anat Rec. 1999;254(2):238–252. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990201)254:2<238::AID-AR10>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Lu Z, Chhatbar PY, O’herron P, Kara P. An artery-specific fluorescent dye for studying neurovascular coupling. Nat Methods. 2012;9(3):273–276. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stekelenburg-de Vos S, Ursem NT, Hop WC, Wladimiroff JW, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Poelmann RE. Acutely altered hemodynamics following venous obstruction in the early chick embryo. J Exp Biol. 2003;206(6):1051–1057. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma R. Untersuchungen über die Histogenese und Histomechanik des Gefäβsystems. Stuttgart: Enke Verlag; 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Thurston GB. The viscosity and viscoelasticity of blood in small diameter tubes. Microvasc Res. 1976;11(2):133–146. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(76)90045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronc F, Mallat Z, Lehoux S, Wassef M, Esposito B, Tedgui A. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Blood Flow-Induced Arterial Enlargement: Interaction with NO. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20(12):e120–e126. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.e120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachi H, Sugitani H, Tajima S, Seyama Y. Endothelin-1 down-regulates expression of tropoelastin and lysyl oxidase mRNA in cultured chick aortic smooth muscle cells. J Health Sci. 2001;47(6):525–532. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenseil JE, Mecham RP. Vascular extracellular matrix and arterial mechanics. Physiol Rev. 2009;89(3):957–989. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenseil JE, Nerurkar NL, Knutsen RH, Okamoto RJ, Li DY, Mecham RP. Effects of elastin haploinsufficiency on the mechanical behavior of mouse arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(3):H1209–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00046.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Bohanan CS, Neumann JC, Lingrel JB. KLF2 transcription factor modulates blood vessel maturation through smooth muscle cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(7):3942–3950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarins CK, Zatina MA, Giddens DP, Ku DN, Glagov S. Shear stress regulation of artery lumen diameter in experimental atherogenesis. J Vasc Surg. 1987;5(3):413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Video 1: Color Doppler of HH36 embryo. Red and blue signals represent flow towards and away from the probe, respectively. Dorsal aortic blood flow is seen on the left, while flow to the embryo’s head is seen on the right.