Abstract

Vibrio cholerae, the causative pathogen of the life-threatening infection cholera, encodes two copies of β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III (vcFabH1 and vcFabH2). vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 are pathogenic proteins associated with fatty acid synthesis, lipid metabolism, and potential applications in biofuel production. Our biochemical assays characterize vcFabH1 as exhibiting specificity for acetyl-CoA and CoA thioesters with short acyl chains, similar to that observed for FabH homologs found in most Gram-negative bacteria. vcFabH2 prefers medium chain-length acyl-CoA thioesters, particularly octanoyl-CoA, which is a pattern of specificity rarely seen in bacteria. Structural characterization of one vcFabH and six vcFabH2 structures determined in either apo-form or in complex with acetyl-CoA/octanoyl-CoA indicate that the substrate binding pockets of vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 are of different sizes, accounting for variations in substrate chain-length specificity. An unusual and unique feature of vcFabH2 is its C-terminal fragment that interacts with both the substrate-entrance loop and the dimer interface of the enzyme. Our discovery of the pattern of substrate specificity of both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 can potentially aid the development of novel antibacterial agents against V. cholerae. Additionally, the distinctive substrate preference of FabH2 in V. cholerae and related facultative anaerobes conceivably make it an attractive component of genetically engineered bacteria used for commercial biofuel production.

Keywords: Vibrio cholerae, β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III, FabH, substrate specificity

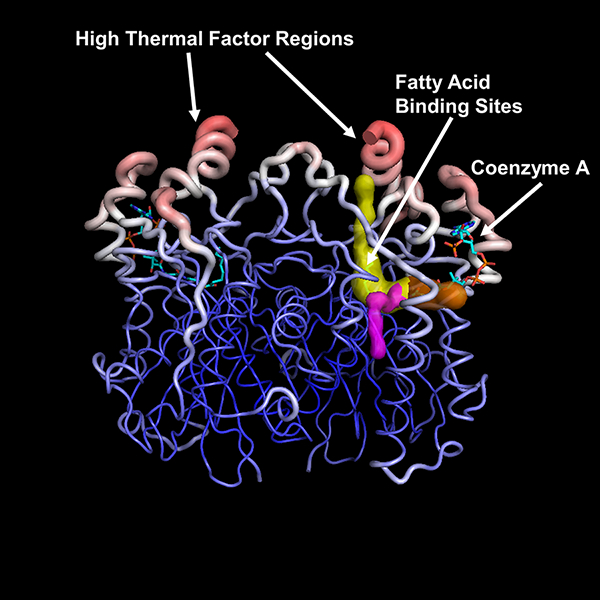

Graphic Abstract

Introduction

The fatty acid synthesis (FAS) pathway is essential for the metabolism of bacteria as well as eukaryotes, and the efficient production of fatty acid by bacteria offers an attractive renewable energy source to plant-based biodiesels or conventional petroleum-based fuels [1]. Unlike the multifunctional eukaryotic fatty acid synthase (FAS I), which performs biochemical transformations by multiple domains in a single protein molecule, bacterial FAS (FAS II) utilizes independent enzymes to catalyze each step of the series of fatty acid synthesis reactions [2]. Studying the interplay and regulation of the multiple components in bacterial FAS II can not only aid the development of unique and highly specific antibacterial agents targeting the FAS II enzymes, but also provide critical knowledge for development of genetically engineered microbial powerhouses for efficient production of advanced biofuels.

Bacterial FAS II is considered an attractive target for the development of new antibiotics [3,4]. Fatty acids, the products of FAS, are indispensable components of biological membranes. Some of the intermediate compounds generated by bacterial FAS II enzymes are also used to synthesize critical cofactors in metabolism (such as biotin and lipoic acid) and other signaling molecules (such as homoserine lactones and quinolones) [5] essential for crucial cell-cell communications devoted to their survival and virulence [6]. V. cholerae, the causative agent of cholera, has caused severe pandemic outbreaks in the past and is still an ongoing threat to human health, especially for people living in developing countries [7]. Effective antibiotic treatments for cholera are in high demand. However, the therapeutic efficacy of current antibiotics is limited by emerging strains of V. cholerae with multidrug resistance (MDR) [8–10], thus the development of an alternate strategy to selectively target V. cholerae with novel antibiotics is of particular importance.

Microbial based biofuel production is an attractive renewable energy solution that can substitute fossil fuels since bacteria can easily be genetically engineered and their maintenance for fuel production can be highly cost effective. The intermediates and final products of FAS II are fatty acids of different lengths, which are readily convertible to alkanes [11] having similar chemical composition to current petroleum-based fuels [12]. Alkanes synthesis using bacteria FAS II is accomplished by the reduction of acyl-ACPs followed by the decarbonylation of the resulting aldehydes [13,14]. The process of decarbonylation can be catalyzed by the overexpression of exogenous aldehyde decarbonylase in Escherichia coli [14]. Metabolic engineering of different components of the FAS II enzymes is vastly explored to increase the yield of fatty acids and expand the fatty acid profile during the overproduction process [15,16]. The thorough mechanistic understanding of microbial fatty acid biosynthesis and biochemical regulation in bacteria will greatly contribute towards the genetic engineering of effective microbes for the overproduction of alkanes as the next generation biofuels.

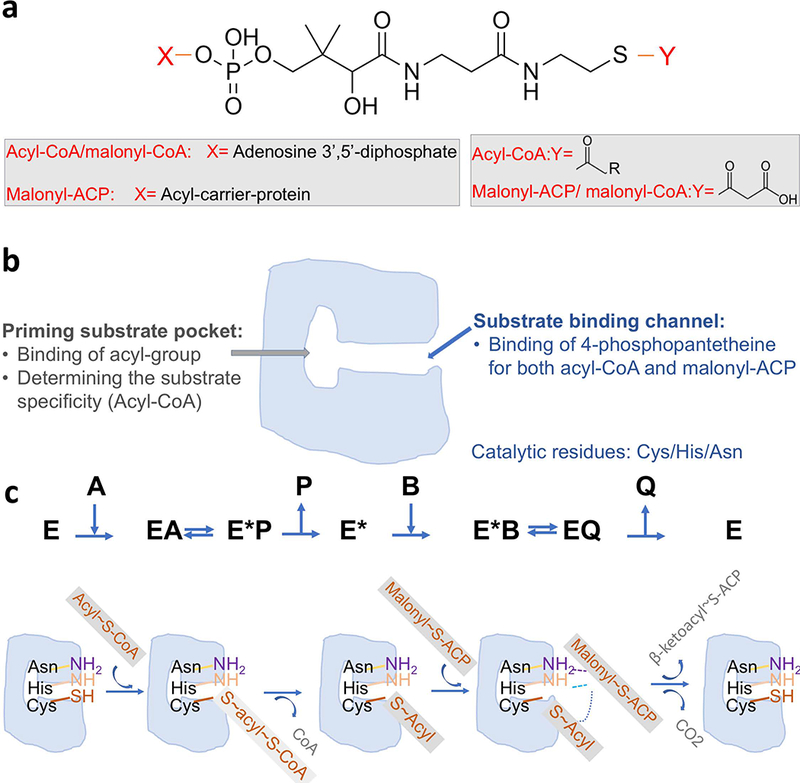

β-ketoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase III (FabH) initiates the first chain elongation cycle in bacterial FAS II by catalyzing the reaction of a primer acyl-CoA molecule and malonyl-(acyl carrier protein) (malonyl-ACP) in a ping-pong mechanism [17,18]. The acyl group from acyl-CoA is first attached to the Sγ atom of the active cysteine residue of free FabH, followed by the release of CoA to form an acyl-FabH intermediate (Fig. 1c). The acyl-FabH intermediate provides the activated acyl group that is transferred to malonyl-ACP to form β-ketoacyl-ACP with a concomitant loss of CO2 (Fig. 1). The product β-ketoacyl-ACP can then be used as a substrate for the β-ketoacyl-ACP reductase (FabG) in the fatty acid synthesis elongation cycle [19].

Figure 1.

Condensation reaction catalyzed by FabH. (a) Structures of the substrates; (b) Schematic drawing for a FabH monomer; (c) Scheme for ping-pong mechanism proposed for FabH. E stands for the FabH enzyme. A stands for the first substrate acyl-CoA. P stands for the first product CoA. B stands for the second substrate malonyl-ACP. Q stands for the second product β-ketoacyl-ACP.

FabH is one of the regulating factors for the composition of fatty acids based on its preferences for various chain-length acyl-CoAs as primer substrates [20]. FabHs from bacteria with membranes predominantly composed of straight-chain fatty acids use primarily short, straight-chain acyl-CoAs as their primer substrate, with a preference for acetyl-CoA. Examples include Gram-negative E. coli and Haemophilus influenza as well as Gram-positive Enterococcus faecalis and Streptococcus pneumoniae [20–23]. In contrast, FabHs from Gram-positive bacteria with >80% of branched fatty acid composition in their membranes preferentially use branched short-chain fatty acyl-CoA as their primer substrate [24]. Examples include Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus [17], Micrococcus luteus [25], and Bacillus subtilis [26], which contain FabH variants that prefer isobutyl-CoA and/or isovaleryl-CoA. Moreover, the substrate specificities of FabH variants may also change upon exposure to harsh environmental challenges such as cold temperature [26,27].

Most bacteria possess a single FabH protein. Some bacteria possess a second protein encoded in a different gene context which engages an acyl-CoA with different lengths of acyl chains as its primer substrate. One example is Bacillus subtilis, in which two copies of FabH with different substrate specificities are responsible for incorporating both straight-chain and branched-chain fatty [26,28]. Ralstonia solanacearum, a plant pathogen, encodes another protein in addition to the FabH protein called RsFabW, which can condense acyl-CoA (C2-CoA to C10-CoA) with malonyl-ACP to produce β-keto-dodecanoyl-ACP [29]. The protein encoded by PA3286 in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 can combine C8-CoA and malonyl-ACP to make the FAS intermediate β-keto decanoyl-ACP [30]. Additionally, P. aeruginosa PAO1 utilizes a new class of divergent β-ketoacyl-ACP synthase called FabY, which carry out the function typical of FabH in other bacteria [31].

V. cholerae encodes two orthologs of FabH—vcFabH1, and vcFabH2 respectively. The vcfabh1 gene is co-localized with genes encoding other proteins involved in de novo fatty acid synthesis on chromosome I, which also contains most of the genes responsible for basic cellular functions. The vcfabh2 gene is located on chromosome II, which hosts many genes responsible for ecological adaptation for survival under altered environmental conditions [32]. In this study, we report the differences in substrate specificity for the two proteins encoded by the vcfabh1 and vcfabh2 genes determined by both binding and enzymatic assays. While acetyl-CoA is the primary substrate of vcFabH1, octanoyl-CoA is the most preferred substrate for vcFabH2. We have also explored the structure-function relationship by determining the crystal structures of both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 with their respective substrates to elucidate the molecular basis for the difference in substrate specificity. Several crystal structures of an inactive mutant vcFabH2(C113A) in its apo form, soaked with octanoyl-CoA, or co-crystallized with octanoyl-CoA were determined to delineate the detailed the structural elements involved in substrate binding.

FabHs’ regulating capabilities on the bacterial fatty acid components make them ideal candidates to diversify the alkane composition in genetically engineered bacteria, thus helping to produce more complex biofuels bearing a close resemblance to petroleum-based fuels. Replacing E. coli FabH with Staphylococcus aureus FabH has been shown to increase the yield of branched chain fatty acids, which has potential to improve the cold-flow properties of advanced biofuels [33]. The addition of Bacillus subtilis FabH2 was reported to significantly increase the yield of 14 and 16 carbons alkanes when compared with the restricted product profile of majorly 13, 15, and 17 carbons alkanes in Escherichia coli [34]. Enzymatic and structural studies on different substrate specificities in vcFabH1/vcFabH2 provided in this work would advance the knowledge that could improve the production of 8, 10, and 12 carbons alkanes towards the synthesis of complex alkane-based biofuels.

Results

Different substrate specificity patterns for vcFabH1 and vcFabH2

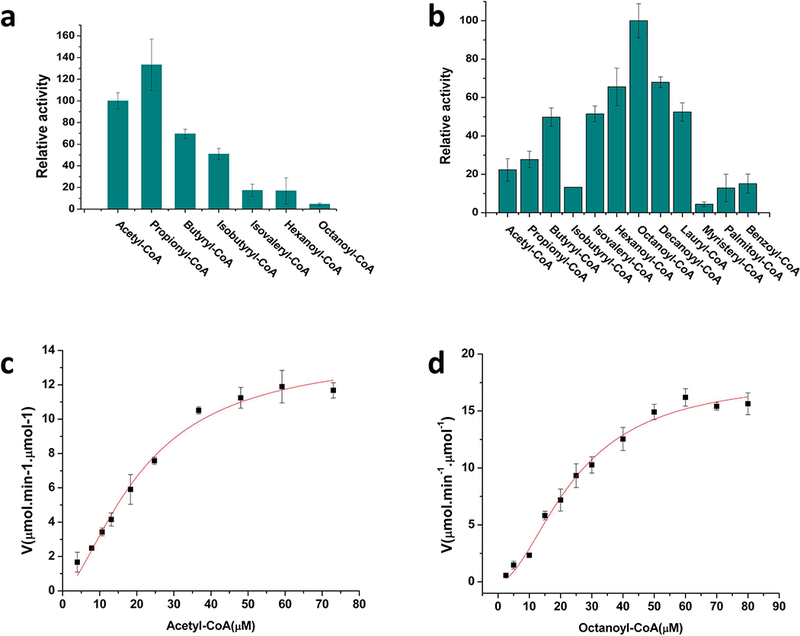

Enzymatic analysis using coupled spectrophotometric methods to measure the conversion of the condensation reaction product β-ketoacyl-CoA into β-hydroxylacyl-CoA revealed that vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 have different patterns of substrate specificity (Fig. 2). vcFabH1 consumes short-chain acyl-CoA (C2-C4) more efficiently than acyl-CoAs with longer carbon chains (C5 or longer) (Fig. 2a). The enzyme utilizes propionyl-CoA (C3) more efficiently than acetyl-CoA (C2). However, because acetyl-CoA is found in much higher concentrations in bacterial cells in vivo [35], it is natural to infer that acetyl-CoA is the major natural substrate for vcFabH1. The reaction rates for butyryl-CoA and isobutyryl-CoA (C4) are ~60%−70% of that of acetyl-CoA, while rates for isovaleryl-CoA, hexanoyl-CoA, and octanoyl-CoA are generally lower than 20% of that of acetyl-CoA. Kinetic analysis showed that vcFabH1 catalyzes the condensation reaction using acetyl-CoA as the primer substrate with a maximum activity of Vmax=14.0±1.1 μmol∙min−1∙μmol−1, a dissociation constant Kd = 21.2±2.9 μM, and a Hill coefficient of n=1.6±0.2 when fitting the data using the Hill equation (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Spectrophotometric coupled enzymatic assay for vcFabHs. Substrate specificity for vcFabH1 (a) and vcFabH2 (b). The reaction solutions contain 50 μM acyl-CoA, 200 μM malonyl-CoA, and 150 μM NADPH in a final volume of 80 μL. The reaction was initiated by the addition of a mixture of 2 μg (0.05 nmol) vcFabH1/vcFabH2 and 14 μg (0.5nmol) vcFabG. The reaction rate for the condensation reaction was monitored by the decrease in absorbance of NADPH at 340 nm by the reduction of β-ketoacyl-CoA at 30°C in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.01% CHAPS, and 1 mM DTT. (c) Enzymatic analysis of vcFabH1 using acetyl-CoA (1–80 μM) as substrate. Vmax=14.0±1.1 μmol∙min−1∙μmol−1, a dissociation constant KD=21.2±2.9 μM, and a Hill coefficient of n=1.6±0.2. Data presented herein are combined results of three repeated tests (sample size n=3). (d) Enzymatic analysis of vcFabH2 using octanoyl-CoA (1–90 μM) as substrate. Vmax=18.0±1.1 μmol∙min−1∙μmol−1, a dissociation constant KD =24.2±2.2 μM, and a Hill coefficient of n=1.8±0.2. Data presented herein are combined results of three repeated tests (sample size n=3).

Kinetic assays also revealed that vcFabH2 processes acyl-CoA analogs with medium length carbon chains (C4-C12) more efficiently (Fig. 2b). The optimal substrate for vcFabH2 is octanoyl-CoA (C8), but decanoyl-CoA (C10) and hexanoyl-CoA (C6) exhibit 60%−70% reactivity as compared with octanoyl-CoA. vcFabH2 catalyzes the condensation reaction using octanoyl-CoA as its primer substrate with a maximum activity of Vmax=18.0±1.1 μmol∙min−1∙μmol−1, a dissociation constant Kd = 24.2±2.2 μM, and a Hill coefficient of n=1.8±0.2 when fitting the data using the Hill equation (Fig. 2d). This reaction rate is of the same magnitude with that of vcFabH1 using acetyl-CoA.

Both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 exhibit strong positive cooperativity in kinetic reactions, with Hill coefficients of n ~ 2, which is in agreement with the dimeric organization of their biological units. The dimeric arrangements of both proteins are also in agreement with their oligomeric states in solution as measured by both size exclusion chromatography and dynamic light scattering (DLS).

Binding assays confirm substrate specificities of vcFabH2

The pattern of binding specificity of vcFabH2 for different acyl-CoA analogs was further confirmed by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). An inactive mutant (C113A) of vcFabH2 was used to avoid the heat generated by the catalytic reaction during the measurement of the binding between vcFabH2 and acyl-CoA variants. The experiments showed that octanoyl-CoA binds to vcFabH2(C113A) with higher affinity (Kd=39±1 μM) than all the other acyl-CoA variants used in the tests (2–12 carbon acyl-CoAs, Kd values ranging from 150–900 μM) except for decanoyl-CoA (C10) (Table 1). However, although the apparent affinity for decanoyl-CoA (Kd=29±1 μM) is higher than that of octanoyl-CoA, the binding stoichiometry for decanoyl-CoA is noticeably greater than that of octanoyl-CoA (1.36±0.01 vs. 0.90±0.01). Most likely this is an indication of non-specific binding of decanoyl-CoA to the enzyme.

Table 1.

Results of ITC experiments: titration of acyl-CoA variants into solutions containing vcFabH2 (C113A) or vcFabH2 (C356A) mutants.

| Acyl-CoA | vcFabH2 mutant | Binding sites/molecule (Stoichiometry) |

Kd (μM) | ΔH (cal∙mol−1) | ΔS (cal∙mol−1∙K−1) |

ΔG (cal∙mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA a | C113A | 0.69 ± 0.05 | >900 | −14490 | −34.70 | −4323 |

| Butyryl-CoA | C113A | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 370 ± 30 | −8259 | −12.00 | −4743 |

| Isobutyryl-CoA a | C113A | 0.77 ± 0.18 | >400 | −8570 | −13.00 | −4761 |

| Isovaleryl-CoA | C113A | 0.74 ± 0.03 | 390 ± 30 | −9347 | −16.20 | −4600 |

| Hexanoyl-CoA | C113A | 0.878 ± 0.004 | 157 ± 3 | −11780 | −22.10 | −5305 |

| Octanoyl-CoA | C113A | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 39 ± 1 | −12670 | −22.30 | −6136 |

| Decanoyl-CoA | C113A | 1.36 ± 0.01 | 29 ± 1 | −7457 | −4.24 | −6215 |

| Lauroyl-CoA | C113A | 1.38 ± 0.02 | 156 ± 11 | −6563 | −4.60 | −5215 |

| Hexanoyl-CoA a,b | C356A | 1 | >600 | −1847 | 8.50 | −4338 |

| Octanoyl-CoA a,b | C356A | 1 | 340 ± 70 | −3414 | 4.43 | −4712 |

| Decanoyl-CoA a,b | C356A | 1 | >900 | −11680 | −25.30 | −4267 |

Weak binding. The Kd shown is an estimate.

The data was processed by fixing N=1. However, the Kd is just an estimation, since the C356A mutant still possesses ~10% enzymatic activity. The titration curve here actually reflects both the binding and kinetic reaction.

Structure overview of wild type vcFabH1 and vcFabH2

The crystal structures of both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 were determined by X-ray crystallography via molecular replacement. Experimental details are described in Materials and Methods section, and the statistics of crystallization and structure determination are summarized in Table 2. Three structures were determined of wild-type vcFabH1 or vcFabH2: vcFabH1 co-crystallized with 5 mM acetyl-CoA to a resolution of 1.78 Å (PDB: 4NHD), apo-vcFabH2 to a resolution of 1.88Å (PDB: 4WZU), and vcFabH2 soaked with 10 mM acetyl-CoA to a resolution of 2.2 Å (PDB: 4X0O).

Table 2.

Crystallization, data collection, and refinement statistics

| Protein | vcFabH1, wild-type, co-crystallized with acetyl-CoA | vcFabH2, wild-type, apo-protein | vcFabH2, wild-type, soaked with acetyl-CoA | vcFabH2, C113A mutant, apo-protein | vcFabH2, C113A mutant, soaked with octanoyl-CoA, no ligand bound | vcFabH2, C113A mutant, soaked with octanoyl-CoA | vcFabH2, C113A mutant, co-crystallized with octanoyl-CoA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB code | 4NHD | 4WZU | 4X0O | 4X9K | 4X9O | 5KP2 | 5V0P |

| DOI of the diffraction images | 10.18430/M3CC7S | 10.18430/M33W2K | 10.18430/M3V88G | 10.18430/M3JP49 | 10.18430/M3PC7K | 10.18430/M35KP2 | 10.18430/M35V0P |

| Crystallization condition | 0.2M CaCl2, 20% w/v PEG3350 |

0.1M Succinic acid pH 7.0, 20% w/v PEG 4K, | 0.22 M Na2 Malonate pH 7.0, 18% w/v PEG3350 | 0.2M Na2 Malonate pH 7.0, 20% w/v PEG3350 | 0.18M Na2 Malonate pH 7.0, 22% w/v PEG3350 | 0.2 M (NH4)3PO4 pH 7.0, 20% w/v PEG 3350 | 0.1M HEPES pH 7.5, 30% v/v PEG400 |

| X-ray source | APS 21ID-G | APS 19ID | APS 19ID | APS 21ID-G | APS 21ID-G | APS 21ID-F | APS 19BM |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9786 | 0.9792 | 0.9792 | 0.9786 | 0.9786 | 0.9787 | 1.2861 |

| Data collectiona | |||||||

| Space group | P212121 | P21212 | P1 | P212121 | P21212 | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) (a, b, c) | 99.5, 100.3, 132.8 | 78.9, 60.2, 68.4 | 61.8, 87.0, 157.3 | 85.5, 61.5, 69.7 | 60.7, 84.3, 134.9 | 84.7,61.2,71.5 | 85.3,61.9,75.8 |

| Unit cell angles (°) (α, β, γ) | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90.06, 89.96, 90.08 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90,94.7,90 | 90,93.2,90 |

| Resolution range (Å)b | 50–1.78 (1.81–1.78) |

50–1.88 (1.91–1.88) |

50–2.20 (2.24–2.20) |

50–1.61 (1.64–1.61) |

50–2.30 (2.34–2.30) |

50–2.00 (2.03–2.00) |

50–2.16 (2.20–2.16) |

| Redundancy | 6.8 (5.4) | 6.4 (5.8) | 1.9 (1.8) | 5.0 (4.0) | 4.4 (4.3) | 2.9 (2.9) | 3.2 (2.6) |

| Rmergeb | 0.091 (0.817) | 0.081 (0.632) | 0.061 (0.294) | 0.068 (0.376) | 0.094 (0.701) | 0.100 (0.413) | 0.057 (0.130) |

| I/σIb | 25.2 (2.0) | 28.0 (2.5) | 14.3 (2.4) | 31.1 (3.2) | 21.0 (2.6) | 12.8 (2.2) | 38.0 (12.0)c |

| Completeness (%)b | 97.6 (87.8) | 99.9 (99.5) | 96.4 (86.7) | 98.3 (87.3) | 96.4 (97.2) | 96.7 (96.9) | 99.3 (98.5) |

| Unique reflections | 18386 | 27070 | 162784 | 47504 | 30242 | 48065 | 42343 |

| Refinementa | |||||||

| Resolution range included (Å) | 50–1.78 | 50–1.88 | 57–2.20 | 50–1.61 | 50–2.30 | 50–2.00 | 50–2.16 |

| Number of protein atoms in ASU | 9548 | 2681 | 21524 | 2729 | 4496 | 5325 | 5302 |

| Number of water molecules in ASU | 1237 | 141 | 725 | 427 | 62 | 379 | 342 |

| Rwork | 0.172 | 0.168 | 0.173 | 0.153 | 0.195 | 0.194 | 0.176 |

| Rfree | 0.196 | 0.202 | 0.201 | 0.176 | 0.233 | 0.221 | 0.207 |

| RMSD from ideal stereochemistry | |||||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.008 | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Mean B value for protein atoms (Å2) | 24 | 35 | 45 | 17 | 47 | 24 | 46 |

| Mean B value for waters (Å2) | 35 | 36 | 35 | 30 | 41 | 31 | 49 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||||||

| Most favored region (%) | 97.2 | 97.2 | 97.0 | 96.9 | 96.8 | 96.9 | 96.6 |

| Additionally allowed region (%) | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| Disallowed region (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shells.

The data was cut off where the I/σI for the highest resolution shell was >2 or the completeness of the highest resolution shell was >85%.

This dataset was processed to its resolution edge.

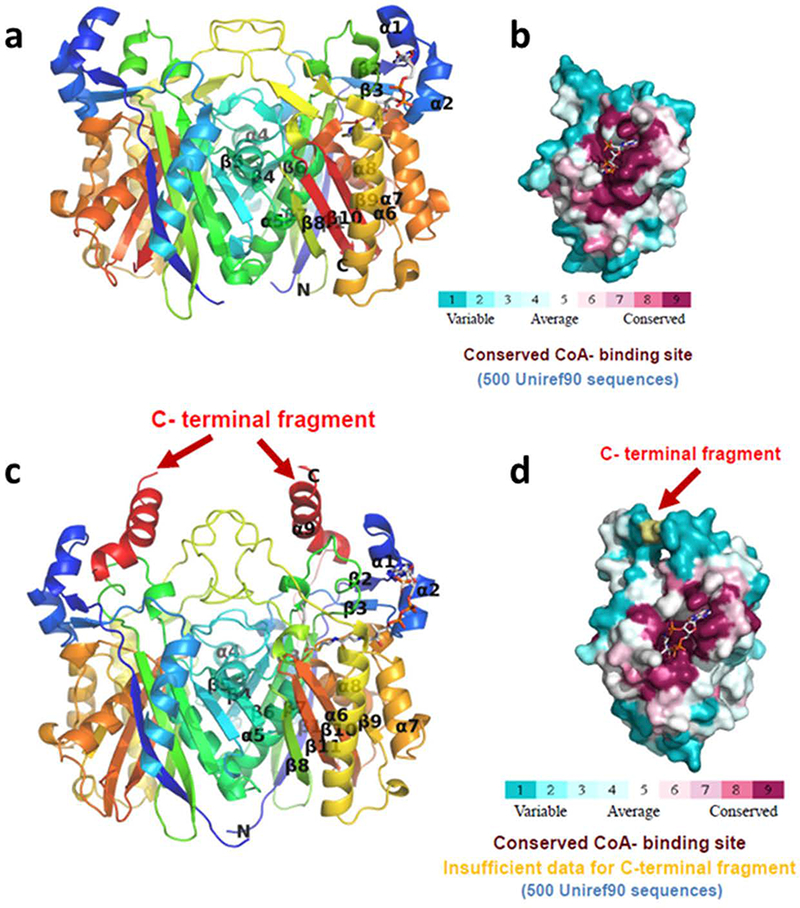

Analysis of crystal contacts by PDBePISA [36] predict that both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 are physiological dimers (Fig. 3a and 3c). This is in agreement with their apparent molecular weights calculated from DLS experiments, which are 65 kDa for vcFabH1 (monomer MW: 33 kDa) and 73 kDa for vcFabH2 (monomer MW: 37 kDa). In addition, the oligomeric states of both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 remain dimeric upon substrate binding as indicated by the hydrodynamic radii (RH) measured in the DLS experiments. The overall architectures of the respective monomers of vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 are similar to each other, as well as to the FabHs from other organisms [17,21,22,37,38]. Superposition of the vcFabH1 and wild type vcFabH2 monomer structures yield an RMSD of 1.1 Å for the 311 aligned Cα atoms. Compared to vcFabH2, vcFabH1 has higher sequence identities to most of the other FabH proteins with known structure (e.g. 72% sequence identity between vcFabH1 and FabH from E. coli, ecFabH, compared to less than 40% sequence identities between vcFabH2 and the other bacterial FabHs with known structures). Correspondingly, the structural similarities of vcFabH1 to other FabH structures (RMSD 0.3–0.7 Å for the 308–317 Cα atoms aligned) are higher than that of vcFabH2 to other FabH structures (RMSD 0.9–1.7 Å for the 289–313 Cα atoms aligned). The overall architectures of vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 are also similar to the structures of other thiolase superfamily enzymes such as PqsD, which mediates the conversion of anthraniloyl-CoA to 2-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline in the quinolone signal biosynthesis pathway (RMSD 1.6–1.9 Å) [39], and OleA, which catalyzes the condensation of two long-chain fatty acyl-CoA substrates in the first step of bacterial long-chain olefin biosynthesis (RMSD ~2 Å) [40].

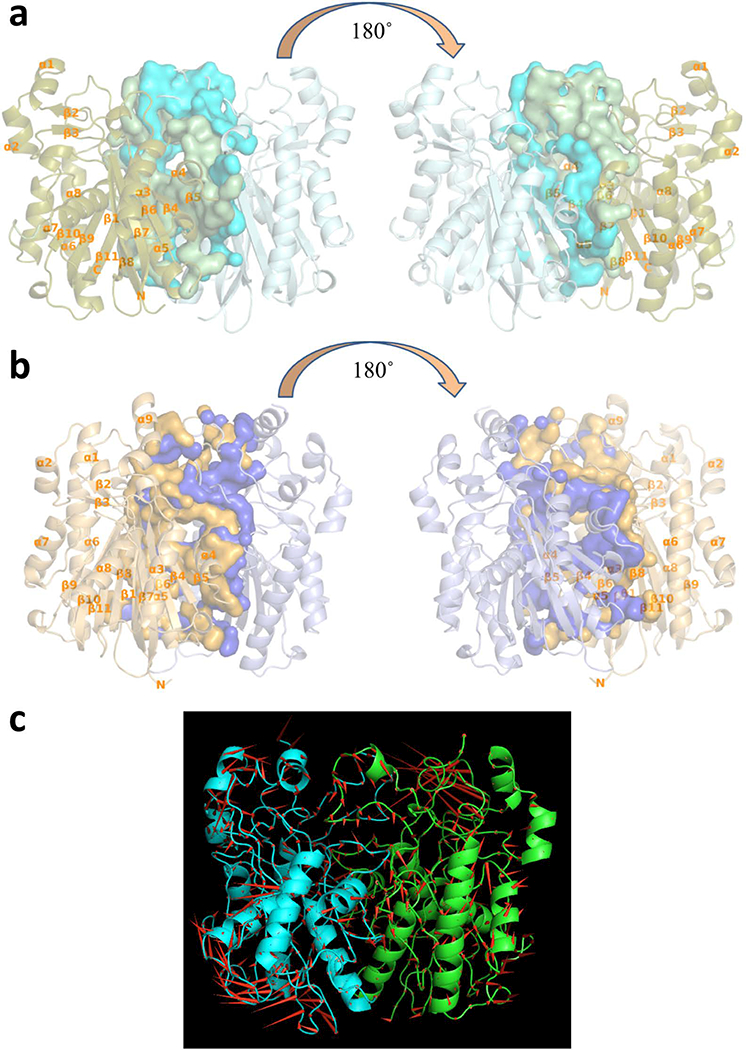

Figure 3.

Crystal structures of vcFabH1 (a, b) and vcFabH2 (c, d). The overall structures of the respective dimers are shown in cartoon representation in “rainbow” representation (a, c), while the molecular surface of each monomer is shown with color corresponding to sequence conservation (b, d). The CoA binding site is conserved. The additional C-terminal fragment unique to FabH2 in certain facultative anaerobic marine bacteria is labeled and shown in red.

Each monomer of both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 is composed of a five-layered α-β-α-β-α sandwich core structure typical for the β-ketoacyl-ACP synthases. The dimer interfaces of both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 involve amino acid residues residing on the loop between β4 and α4 (Loop 1), α4, β5, α5, the loop between β6 and α6 (Loop 2), β8 and the loop between β8 and α6 (Loop 3) (secondary structure elements are identified in Fig. 4). The L-shaped substrate binding channel leads from the middle part of the monomer and stretches through the center of the molecule, lined mostly with amino acid residues from one monomer and one residue from the other monomer (Phe87’ in vcFabH1 and Ile88’ in vcFabH2). The catalytic triad (Cys112, His246, and Asn268 in vcFabH1; Cys113, His251, and Asn281 in vcFabH2) are located at the transition of the two arms of the L-shaped substrate binding channel. The most notable structural difference in vcFabH2 as compared to vcFabH1 is the presence of an extended C-terminal fragment (Fig. 3c) composed of an additional 36 amino acids (Gly325-Gln360). This extended C-terminal fragment of vcFabH2, as described in more detail below, not only contributes to dimer formation, but also interacts with the substrate binding site.

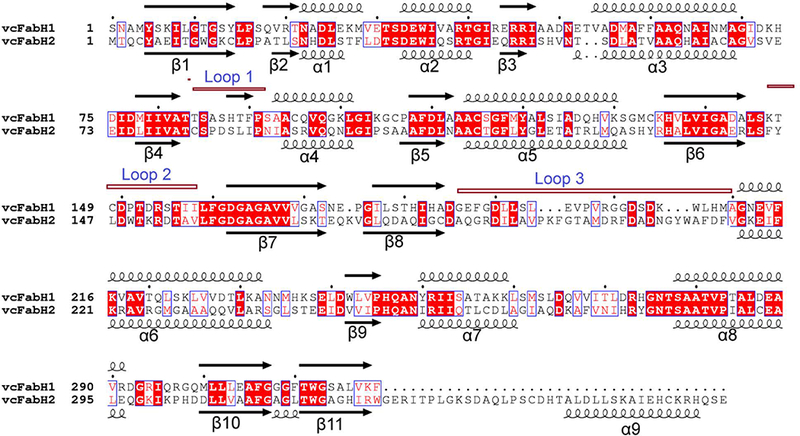

Figure 4.

Alignment of vcFabH1 with vcFabH2. The amino acid sequences for the two proteins were aligned using ClustalW. The secondary structures were assigned by DSSP, with 310 helices and short turns omitted for clarity. Conserved residues are highlighted in boxes. The loops involved in the formation of dimer interface are annotated as Loop 1 (the loop between β4 and α4), Loop 2 (the loop between β6 and α6), and Loop 3 (the loop between β8 and α6). The figure was generated using ESPript (http://espript.ibcp.fr).

Dimer interface in vcFabH1 and vcFabH2

Despite the similarity in the secondary structures of the fragments composing the dimer interfaces, vcFabH2 exhibits a significantly larger interface area (~3100 Å2) involving 84 amino acid residues, compared with that of vcFabH1 (~2400 Å2) involving 68 residues (Fig. 5a and 5b). This dissimilarity can be attributed to differences in Loops 2 and 3 of the two proteins (Fig. 4). Although the conformations of the main chains are similar, Loop 2 of vcFabH2 contains more hydrophobic residues with much bulkier side chains than those of vcFabH1. An insertion of six amino acid residues starting from residue Ile190 in Loop 3 of vcFabH2 leads to a major change in the main chain configuration, resulting in a relative displacement of 2–7 Å for Cα atoms in this fragment compared with that of vcFabH1. Moreover, as in Loop 2, residues in Loop 3 of vcFabH2 are generally bulkier and more hydrophobic as well. Three residues (Ala352, His355, and Cys356) in the extended C-terminal fragment of vcFabH2 also contribute to the dimer formation. Together these factors result in ~700 Å2 more area for the dimer interface in vcFabH2 compared to that of vcFabH1. The dimer interface area of vcFabH1 is similar to that of those FabHs which preferentially use acetyl-CoA as their substrate, such as ecFabH [17,38], while the larger dimer interface in vcFabH2 is similar to that of FabH from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (~3100 Å2), an enzyme known to use long-chain (C12–C20) fatty acyl-CoAs as a substrate [41,42]. A “porcupine map” [43] was used to visualize the direction and extent of the principal motions of the vcFabH2 dimer (Fig. 5c). Overall, the secondary structures near the surface of the molecule exhibit much higher flexibility when compared with the dimer interface and its immediate neighbors. Several major concerted movements near the surface of vcFabH2 were discovered, which are in agreement with the more flexible fragments (i.e., those with high B factors) as observed in the structures. Briefly, the first concerted movement is at the top of the protein centered on the α9 and the loop between β11 and α9. The second concerted movement is located at the bottom of the molecule involving the loop between β7 and β8, α8, and the loop between α8 and β10. The third concerted movement is on the side of the molecule involving the residues from helix α6 [44].

Figure 5.

Dimer interfaces of vcFabHs. (a) Front and back view of vcFabH1 dimer; (b) Front and back view of vcFabH2 dimer. Secondary structure elements are shown in cartoon representation and labeled from α1-α8 (α1-α9 in the case of vcFabH2) and β1-β11. Residues involved in the formation of the dimer interface are shown in surface representation. (c) The highest eigenvector of the backbone atomic motion as seen in molecular dynamics simulations of the vcFabH2 dimer complexed with octanoyl-CoA is pictured as a porcupine plot. Arrows (the red cones) point in the direction of motion for each backbone atom, and the length of each arrow represents the magnitude of the motion. vcFabH2 is shown in ribbon representation, and the two subunits are colored in green and cyan respectively.

CoA/malonyl-(acyl carrier protein) binding in vcFabH1 and vcFabH2

Like the other FabHs with known structures, the acyl-CoA/malonyl-ACP binding site in both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 is composed of an L-shaped channel leading from the surface into the center of the molecule [17,38,41]. This L-shaped channel is composed of a set of conserved residues adjacent to the outlet of the channel on the protein surface and is assumed to anchor both substrates acyl-CoA and malonyl-ACP on the protein for reaction (Fig. 3b and 3d). The amino acid residues responsible for CoA/malonyl-ACP binding in vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 are almost identical, which seems to be a common feature of all FabHs with known structures (Fig. 3b and 3d). Complex structures of the vcFabH1 crystal co-crystallized with acetyl-CoA (PDB: 4NHD) and the vcFabH2 crystal soaked with acetyl-CoA (PDB: 4X0O) demonstrate that the binding mode of CoA is similar to that of the other FabHs with known structures [17,38,41,42]. In 4NHD, CoA molecules are present in all four chains in the asymmetric unit (ASU), and the active site cysteine Cys113 is acetylated. In 4X0O, only one full CoA molecule was modeled in one of the eight chains in the ASU, while partial fragments of CoA are modeled in other subunits. The L-shaped channel in these two crystal structures is composed of three parts: 1) the shorter “arm” of the L-shaped channel that hosts the adenine ring/ACP moiety; 2) the pyrophosphate connecting the acyl moiety to the adenine ring/ACP moiety; 3) the longer “arm” of the L-shaped channel accommodates the hydrophobic acyl moiety, which is also referred to as the “priming substrate pocket”.

The adenine ring of CoA is sandwiched between the hydrophobic clamp formed by the side chains of a conserved tryptophan residue and a conserved arginine residue (Trp32 and Arg151 in vcFabH1, or Trp35 and Arg152 in vcFabH2) (Fig. 6). Hydrogen bonds between N1A and N6A atoms of CoA and Oγ of a conserved threonine residue (Thr28 in vcFabH1, or Thr31 in vcFabH2) help lock the adenine ring. While there is no structure of FabH in complex with ACP, a patch of positively charged basic residues are proposed to interact with the negatively charged acidic residues on the α2 helix of ACP to anchor the carrier protein to the FabH surface [45].

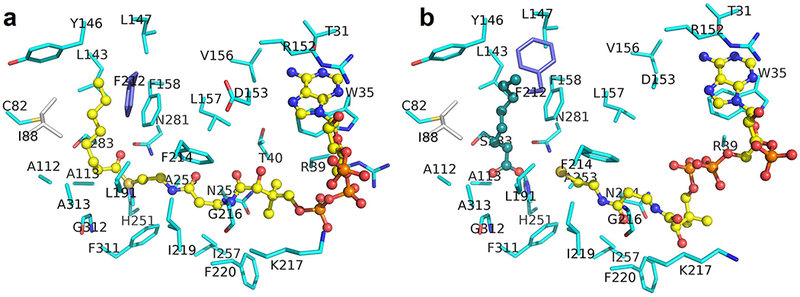

Figure 6.

Binding of octanoyl-CoA to vcFabH2 in (a) structure with octanoyl-CoA bound (PDB: 5V0P) and (b) structure with degraded priming substrate (PDB: 5KP2). Most of the carbon atoms in amino acid residues from one monomer are shown in cyan. Carbon atoms for residues of the catalytic triad (with C113A mutation) are shown in gold, while that from the other monomer are shown in gray. Carbon atoms in CoA analog are shown in yellow. The carbon atoms in octanoic acid are shown in dark green. Phe212 is shown in blue to highlight its conformational difference. In 5KP2, the side chain of Phe212 is flipped ~90o to make more room to accommodate the ligand.

The pyrophosphate group connecting 4’-phosphopantetheine may be stabilized by the salt bridges and hydrogen bonds with side chains of conserved basic residues (Arg36 and Arg248 in vcFabH1, or Arg39, Lys217, and Arg256 in vcFabH2), although the side chains of these residues might not always be visible on the electron density map.

The 4’-phosphopantetheine “arm” sits in a hydrophobic channel formed by the side chains of a group of conserved residues (Phe212, Gly208, Asn209, Met206, Phe303, Ala245, Leu156, Phe157, Ile249, and Val211 in vcFabH1, or Phe220, Gly216, Lys217, Phe214, Phe311, Ala253, Leu157, Phe158, Ile257, and Ile219 in vcFabH2). The longer end of the L-shaped channel, which accommodates the 4’-phosphopantetheine “arm”, extends for ~20 Å leading from the surfaces of the enzymes to the buried catalytic residues (Cys112, His243, and Asn273 in vcFabH1, or Cys113, His251, and Asn281 in vcFabH2) with a diameter of ~ 5 Å, then meets with the shorter end of the L-shaped channel, a hydrophobic pocket which accommodates the acyl-group of the acyl-CoA variants (the priming substrate pocket).

In all the FabHs with known structures, the priming substrate pocket is at the center of the molecule and is composed mostly of residues from one monomer and one residue from the other. The pocket varies in shape and size in different FabHs (Fig. 7), which is thought to determine the substrate specificity of each FabH enzyme [17,41,42]. In vcFabH1, the priming substrate pocket is composed of amino acid residues Leu142, Phe157, Leu189, Leu204 and Phe87’, which creates a cavity with a volume of ~200 Å3, similar to that of FabH from E. coli (ecFabH), which prefers acyl-CoA as its substrate [22]. The observed volume of the priming substrate pocket is in agreement with its pattern of substrate specificity (for short-chain acyl-CoA variants) as demonstrated in enzymatic assays.

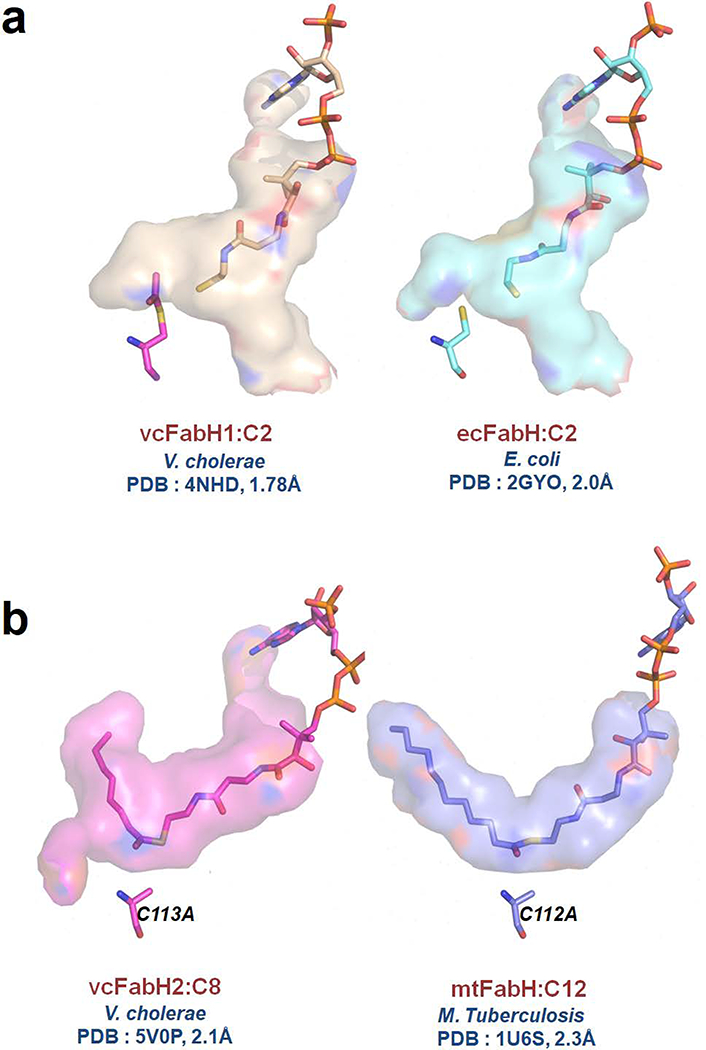

Figure 7.

CoA and substrate binding sites of FabHs. (a) The substrate binding site of vcFabH1 (PDB code: 4NHD) is compared with that of ecFabH (PDB code: 2GYO). (b) The substrate binding site of vcFabH2 (PDB code: 5V0P) is compared with that of mtFabH (PDB code: 1U6S).

The priming substrate pocket of vcFabH2, which is composed of amino acid residues Cys82, Ala112 Leu143, Tyr146, Phe158, Leu191, Val193, Phe212, Phe311, Gly312, Ala313 and Ile88’, has a cavity with a diameter of ~7.5 Å, a depth of ~13 Å, and a volume of ~600 Å3. This priming substrate pocket of vcFabH2 appears to be smaller than that of FabH from M. tuberculosis (mtFabH), which is specific for long-chain acyl-CoA substrates (with a similar diameter but a longer depth of ~18 Å, and a cavity volume of ~800 Å3) (Fig. 7) [41]. The size of the priming substrate pocket in vcFabH2 indicates that its substrate specificity may favor medium chain acyl-CoA variants—i.e. those with longer acyl groups than acetyl-CoA, as in the case of ecFabH [22,38], but shorter than the acyl group in dodecyl-CoA, as in the case of mtFabH [41]. This concurs with the kinetic assays that showed that vcFabH2 prefers octanoyl-CoA as its substrate.

The extended C-terminal fragment in vcFabH2

As noted above, a 36 residue extension of the C-terminus of vcFabH2 (Gly325-Gln360) is the most obvious structural difference of vcFabH2 as compared to vcFabH1 (Fig. 3c). A BLAST search of the NCBI non-redundant protein database reveals that this additional fragment exists exclusively in FabHs from certain Gram-negative marine bacteria that live in similar conditions as V. cholerae. These bacteria mostly belong to the genera Vibrio, Shewanella, Aeromonas, Alteromonas, or Pseudoalteromonas. Some of these bacteria have been demonstrated to be facultative anaerobes that cause opportunistic gastrointestinal infection in human [46] or sea animals [47].

In the structure of vcFabH2, this additional C-terminal fragment extends the C-terminus of the core structure and wraps around the core of the same monomer in the dimeric structure (Fig. 8a). The extra C-terminal fragment of vcFabH2 comprises a loop (Gly325-His343) and an α-helix (Thr344-Gln360). The first half of the extended C-terminal fragment (Gly325-His343) forms extensive hydrophobic interactions with the core structure in the form of an ordered loop that interacts with the N-terminus (Fig. 8a, colored blue). The second half of the C-terminal fragment (Thr344-Gln360) forms an α-helix interacting with the CoA/malonyl-ACP binding loop on one side, and with the dimer interface (loop 2) on the other side (Fig. 8a).

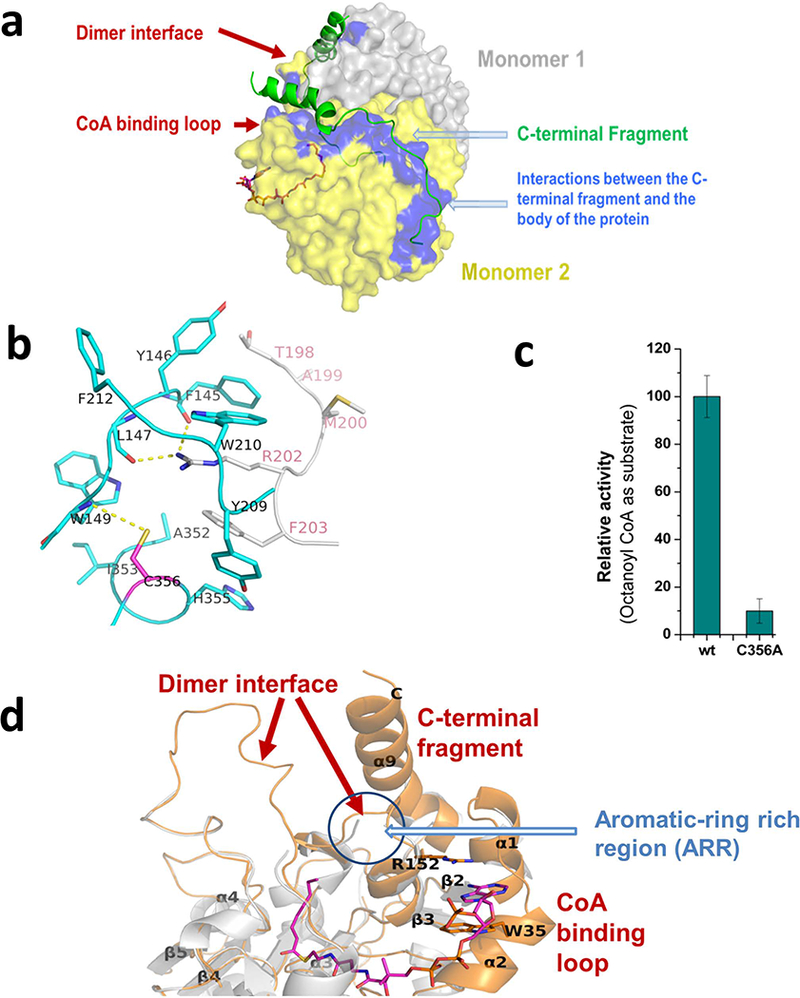

Figure 8.

C-terminal fragment of vcFabH2. (a) Interactions within the vcFabH2 dimer. (b) Cys356 (with side chain shown in magenta) is involved in the formation of the dimer interface via the aromatic-ring rich region (ARR). (c) The relative enzymatic activity of the C356A mutant is only 10% of the activity of the wild-type vcFabH2. Catalytic rate of FabH2 (wt.) was set as 100% (data combined from three tests: 100 ± 8%), while that of FabH2 (C356A) was 10 ± 5% (data combined from three tests). (d) Structural changes during substrate binding. The ordered CoA-binding loop/dimer interface/C-terminal fragment is shown in orange in the case of apo-vcFabH2 (PDB: 4WZU) and vcFabH2 complexed with octanoyl-CoA (PDB: 5V0P), while the disordered CoA binding loop/dimer interface/C-terminal fragment is shown in gray in the case of vcFabH2 soaked with octanoyl-CoA, where no ligand was found (PDB: 4X9O).

Close examination of the interactions between the C-terminal α-helix and the dimer interface reveals that His355 interacts directly with Phe203 from the opposing chain, while a hydrogen bond between Cys356 and Trp149 [48] contributes indirectly to stabilization of the dimer interface by mediating two hydrogen bonds between the main chain oxygen of Phe145/Leu147 and Arg202 from the opposing chain (Fig. 8b). This hydrogen bond between Cys356 and the main chain nitrogen atom of Trp149 anchors the C-terminal α-helix to an aromatic-ring rich region (ARR) comprising two tryptophan residues (Trp149 and Trp210), two tyrosine residues (Tyr146 and Tyr209), and two phenylalanine residues (Phe145 and Phe212). The ARR in the vicinity of Cys356 is directly involved in the formation of the dimer interface and may be involved in substrate binding (Fig. 8d).

The key role of Cys356 in maintaining catalytic activity of vcFabH2

Cys356 is part of the C-terminal α-helix and is in the proximity of both the substrate binding site and the dimer interface. In addition to the aforementioned Cys356-Trp149 hydrogen bond, Cys356 is also identified by the program CSS-Palm as a potential palmitoylation site in the sequence x-x-x-C356-x-x-x [49]. Collectively, this structural evidence suggests that Cys356 is critical for the structural stability and enzymatic activity of vcFabH2.

The mutation C356A in vcFabH2 results in a ~90% loss of enzymatic activity as compared with the wild type protein (Fig. 8c). This loss of activity is most likely caused by the reduced binding capacity of the enzyme for the substrate. ITC experiments showed that the Kd of octanoyl-CoA binding to the C356A mutant is ~340 μM, which is almost 9 fold poorer than that of the C113A mutant, which lacks the interactions between the active Cys113 residue and the substrate.

The purified protein of vcFabH2 (C356A) mutant was used to set up crystallization trials for potential subsequent structural studies. The C356A mutant shares a similar profile in size exclusion chromatography with wild type vcFabH2. However, extensive crystallization screening trials did not yield any C356A crystal, indicating the importance of Cys356 for the stabilization of both the C-terminal α-helix and the surrounding ARR structural element in order not to disturb the molecular contacts favorable for crystallization.

Structural changes at the vcFabH2 (C113A) mutant substrate binding site upon octanoyl-CoA binding

Mutation C113A eliminates the acyl-transferase activity of vcFabH2. The structure of the vcFabH2(C113A) mutant was determined at 1.61 Å (PDB: 4X9K), with an RMSD of 0.3 Å for the 358 Cα atoms aligned when compared with the wild type protein. The vcFabH2(C113A) mutant showed no enzymatic activity using the coupled spectrophotometric assay, yet retains the capability to bind acyl-CoA variants as demonstrated by ITC experiments.

Crystallization trials were conducted in an attempt to obtain crystal structures of vcFabH2(C113A) in complex with the most preferred substrate (octanoyl-CoA) or other substrates (hexanoyl-CoA and decanoyl-CoA) of vcFabH2. All the drops containing a mixture of vcFabH2(C113A) and decanoyl-CoA or hexanoyl-CoA in co-crystallization experiments contained amorphous precipitant. All efforts to soak well-shaped, diffracting crystals in decanoyl-CoA solutions resulted in dissolution of the crystals, but some vcFabH2(C113A) crystals soaked with either hexanoyl-CoA or octanoyl-CoA remained intact and were used for diffraction experiments. However, many of these structures do not have density clear enough to model a ligand in the priming binding pocket. Soaking with either hexanoyl-CoA or octanoyl-CoA seems to perturb the structure since the area responsible for substrate binding and the dimer interface showed significant disorder. Only one representative structure (2.3 Å) of a vcFabH2(C113A) mutant crystal soaked with 5 mM octanoyl-CoA for ~5 minutes was fully refined and deposited to the PDB (PDB: 4X9O). However, octanoyl-CoA could not be modeled into this structure. This structure exhibits a substantially similar scaffold to that of the apo-protein, with an RMSD of 0.4 Å for all the 315 Cα atoms in the core part of the enzyme aligned. In structure 4X9O, more than 40 amino acid residues composing helices α1 and α2, Loop 2 and Loop 3, and the C-terminal helix α9 could not be modeled (Fig. 9). The missing residues include Trp35 and Arg39 on helix α2, and Arg152 on Loop 2, which are directly involved in the binding of the adenine moiety of the CoA variant on the protein surface (Fig. 6). The residues surrounding Cys356 are completely disordered, most prominently in the aromatic-ring rich region, as all six aromatic amino acid residues in this region could not be modeled (Fig. 8d). The missing residues also include helix α1, Loop 2 and the C-terminal helix α9 (secondary structure elements are identified in Fig. 4), which does not directly interact with the substrate or the dimer interface but rather forms hydrophobic interactions and forms the backbone in the apo-protein.

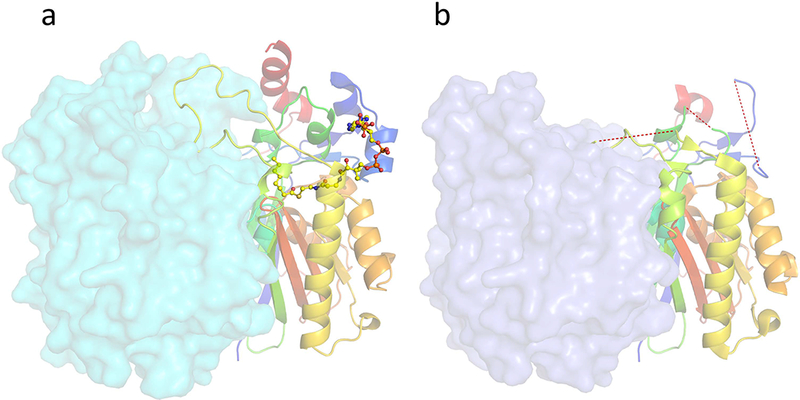

Figure 9.

Conformational changes upon priming substrate octanoyl-CoA binding in vcFabH2. One monomer is shown in cartoon mode in “rainbow” representation, while the other monomer is shown in surface mode. (a) The ordered loops in the apo- and octanoyl-CoA complexed vcFabH2 are shown as a continuous carton trace from the backbone. Octanoyl-CoA is shown in ball and stick mode. (b) The disordered region of 4X9O is highlighted by a red dashed line.

Structure of vcFabH2(C113A) mutant with octanoyl-CoA bound

A crystal of the vcFabH2(C113A) mutant grown in acidic conditions (Table 2) and soaked with 5 mM octanoyl-CoA overnight diffracted to a resolution of 2 Å (PDB: 5KP2), and another crystal of vcFabH2(C113A) co-crystallized with 5 mM octanoyl-CoA at a neutral pH diffracted to a resolution of 2.16 Å (PDB: 5V0P). The crystal structures of both vcFabH2(C113A) complexes were determined. In structure 5KP2, one of the two subunits in the asymmetric unit does not have a ligand bound/modeled. The other subunits in 5KP2 were modeled with an octanoic acid molecule at the priming binding pocket with full occupancy and a coenzyme A molecule was modeled in the CoA binding channel with partial occupancy of 0.6. In structure 5V0P, octanoyl-CoA with partial occupancy of 0.6 was modeled in both subunits. The subunit of structure 5KP2 without a bound ligand and both subunits in structure 5V0P are almost identical to that of apo-vcFabH, with an RMSD of only 0.2 Å over all the Cα atoms aligned.

The subunit with ligand bound in structure 5KP2 shares a similar overall structure to the apo-protein, too, with an RMSD of 0.6 Å for all the Cα atoms aligned. However, parts of the subunits exhibit significant structural differences. Two sets of residues shift 0.9 to 1.8 Å toward the surface of the molecule, including 1) the Cα atoms for residues on helices α1, α2, and Loop 2 which provide securing interactions with the adenine moiety of the CoA variant, and 2) the Cα atoms on Loop 3 and part of helix α6 which provide a “lid” for the CoA binding channel. The combined effects result in a wider CoA binding channel (~1.5 Å) in structure 5KP2 than in that of the apo-protein.

In both 5KP2 and 5V0P, the binding of the adenine ring of the CoA analog is secured by interactions with the conserved residues Trp35, Arg152, and Thr31 (Fig. 6). While the electron densities corresponding to the second phosphates in the PPI group of CoA are poor in both cases, the binding of CoA in 5KP2 appears to be even looser than that in 5V0P. Nevertheless, both the octanoic acid molecule in 5KP2 and the octanoyl moiety of octanoyl-CoA in 5V0P fit well in the priming substrate pocket with enriched hydrophobic residues. The only difference is that the side chain of Phe212 in structure 5KP2 flips 90 degrees toward the surface of the molecule, resulting in a slightly larger priming substrate pocket which may accommodate a larger substrate or product.

Discussion

Significance of two copies of FabHs in V. cholera: The extra copy of FabH in certain facultative anaerobic marine bacteria may be related to adaptation to ecological stress.

V. cholerae exhibits a complex life cycle with transitions between the aquatic environment, where it survives in biofilms during inter-epidemic periods, and in the human gastrointestinal tract, where it acts as a pathogen [44,50]. The bacterium has evolved with an intricate mechanism for survival in harsh environments, including biofilm formation and the use of chitin as carbon and nitrogen sources in aquatic medium, as well as mechanisms for survival in the acidic environment of the human stomach. The transitions of V. cholerae between different conditions along its life cycle require physiological adaptations of the pathogen. One such acquired metabolic adaptation is the ability to manipulate the fatty acid composition of cell membranes. V. cholerae is able to utilize available nutrients and substrates from the host and aquatic environments to alter its metabolism for synthesis of selective fatty acids to incorporate into its membrane [51,52]. It has been demonstrated that its phospholipid ester-linked fatty acid profile changes during nutrient deprivation [53]. Nevertheless, de novo fatty acid synthesis is always a critical component of the survival of the pathogen. β-ketoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase III (FabH) plays a vital role in the bacterial lipid metabolism as the enzyme initiating the chain elongation cycle of fatty acid synthesis.

vcFabH2 has an unique extended C-terminal fragment of 36 amino acids with unknown biochemical function that is absent in FabH1 and most other FabH2 homologs from other organisms. A BLAST search [54] against the Uniref90 database [55] revealed that the extended C-terminal fragment is absent in most of the FabH proteins, as well as in other homologous condensation enzymes and therefore may be of high significance to V. cholera. Such an extended FabH sequences of C-terminal fragment are scarce and less commonly observed in the Uniref90 database. A close survey of the organisms that possess FabH proteins with extended C-terminal fragments revealed that these organisms are all facultative anaerobic marine bacteria in the Vibrionaceae family, including V. cholerae, Idiomarina loihiensis, Photobacterum profundum, etc. or from the Pseudoalteromonadaceae family, such as Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis. This suggests that in order to survive in vastly different environments, these bacteria have evolved with a mechanism to alter the metabolism to suit the need and effectively utilize the available nutrients.

Correlation of substrate specificity and the size of the primer-binding channel in vcFabHs indicates the potential of vcFabH2 to improve the production of medium-chain length fatty acids

Both vcFabH1 and vcFabH2 share a common core structure similar to all the other FabHs, which is a five-layered α-β-α-β-α sandwich structure commonly found in condensation enzymes. The dimeric arrangement for both vcFabHs in the solution state and in the crystal structures is consistent with the functional quaternary unit of all FabHs structures determined to date [17,38,42].

Among the three most efficient substrates of vcFabH2—octanoyl-CoA, decanoyl-CoA, and hexanoyl-CoA—it is worth noting that the substrate with highest binding affinity to vcFabH2 is decanoyl-CoA (Table 1) and yet the most reactive substrate is octanoyl-CoA (Fig. 2b). The pattern of substrate specificity and observed binding affinity suggest that C-6, C-8, and C-10 carbon chains are highly recognized by this protein and form stable substrate-enzyme complexes. It is worth mentioning here that C6 as substrate can be converted to C-8 product and C-8 as substrate can be converted to C-10 fatty acid as product. The most plausible rationale that can be offered here is that vcFabH2 uses octanoyl-CoA as the most optimal substrate, which becomes decanoyl-CoA upon condensation with malonyl substrate. Therefore, both the substrate octanoyl-CoA and the product decanoyl-CoA were exhibiting similar affinity to vcFabH2. Moreover, vcFabH2 could catalyze several condensation reactions in series albeit with poor efficiency, but both hexanoyl-CoA and octanoyl-CoA are observed to be optimal substrates. The hydrophobic domain has an elongated channel in the active site, which supports the observed high binding affinity with medium size (C-6 to C-12) acyl chains (Table 1). However this hydrophobic channel of vcFabH2 is not long enough to accommodate myristoyl-CoA, which correlates with the significant drop in observed reaction rate with myristoyl-CoA as substrate (Fig. 2b).

A current limitation of microbial-based alkane production is the restricted product profile mainly consisting of odd-chain alkanes. It has been reported that E. coli produces only odd-chain alkanes in significant amount due to lack of FabH2, upon expressing FabH2 into the system expands the product profile to include significant amount of even-chain alkanes (C14 and C16) [34]. The observations made in this study about vcFabH2 structure-function for selective choice of substrates further advances the knowledge to produce known chain lengths of fatty acids as a tailor made desired option. It has potential application in biofuel production expanding the alkane profile to include medium size even-chain alkanes (C6 to C12), however we do not have data that would support this hypothesis. The detailed understanding of structural aspect of hydrophobic domain for selectivity of substrate chain lengths shed light on possibility of manipulating this domain via genetic engineering to fine tune the production of well defined fatty acids.

The role of extended C-terminus of vcFabH2: Changes in the conformation of dimer-forming loops may serve as switch for the binding of primer substrate and the release of product

The structures of apo-vcFabH2 and the vcFabH2(C113A) mutant both contain an ordered dimer interface and an aromatic-ring rich region (ARR), an ordered CoA binding loop, and an ordered C-terminal helix. However, the crystal structure of a vcFabH2(C113A) soaked with octanoyl-CoA lacks a clearly bound ligand, the majority of the C-terminal helix cannot be modeled due to the poor electron density corresponding to this region. The CoA-binding helices and the dimer interface are also disordered. We hypothesize that the ensemble of residues becoming disordered upon octanoyl-CoA soaking compose the entrance of the substrate binding site, while the captured conformation with disordered regions represents a transition state in which the entrance of the substrate binding pocket is opened wide to allow for the entrance of the substrate. Soaking with octanoyl-CoA for 5 minutes could have disturbed the conformation of all residues composing this entrance of the substrate binding site (Fig. 9b). However, in the structure with octanoyl-CoA bound, these disordered fragments are reorganized and adopt a conformation similar to the conformation of the residues at the entrance of the substrate binding pocket in the apo-protein. These residues in the octanoyl-CoA bound vcFabH2(C113A) structure exhibit a much higher B factors which suggest high flexibility.

Our results demonstrate that the extended C-terminal fragment of vcFabH2 plays critical roles in stabilizing part of the dimer interface. The importance of Cys356 for the enzymatic activity is confirmed by kinetic assays (Fig. 8c). We hypothesize that Cys356 could be a key residue for restoring the ordered conformation around the substrate binding pocket from the potential transition state with disordered residues. The formation of a C356-W149 hydrogen bond could be the final step to lock the substrate in place and restore the entrance of the substrate binding pocket back to the ordered conformation. According to this hypothesis, the C356A mutant can neither lock the substrate in place nor restore the entrance of the substrate binding pocket to the originally ordered conformation, since it cannot form the critical C356-W149 hydrogen bond upon substrate binding. An increase in local surface entropy around the entrance to the substrate binding site is also suggested by the observation that C356A failed to form crystals despite numerous attempts at a wide variety of crystallization screening conditions.

Our results suggest that the extended C-terminal fragment of vcFabH2 could regulate the enzyme activity by interacting with the dimer interface, by interacting with the ARR and the CoA-binding loop, and/or by mediating interactions with other proteins such as ACP. The mutation of a cysteine residue (C356A) at the C-terminal fragment of vcFabH2 is shown to abolish enzymatic activity (Fig. 8c). This raises the hypothesis that this altered C-terminal α-helix could interfere with substrate binding and corresponding enzymatic activity by directly regulating the substrate binding or by interacting with other proteins. The results about the key role Cys356 plays in the fatty acid condensation reaction in V. cholerae pinpoint a hotspot that could be targeted for the discovery of novel antibacterial agents specifically targeting organisms containing FabH2.

Experimental procedures

Cloning, protein expression, and purification

The coding sequences for β-ketoacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) synthase III (vcFabH1, CSGID target IDP01441) and β-ketoacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) synthase III-2 (vcFabH2, CSGID target IDP01493) were chemically synthesized (Genscript, USA) and cloned into the pMCSG7 vector [56]. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate the vcFabH2(C113A) mutant. All recombinant plasmid pMCSG7-vcFabHs were transformed into E. coli strain BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIPL competent cells (Stratagene). The E. coli cells carrying recombinant plasmid for pMCSG7-vcFabHs were cultured in Luria Broth (LB) media at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of around 0.7. Expression of protein was induced by addition of 0.25 mM isopropyl-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The induced cells were grown at 16°C overnight.

Recombinant vcFabHs with N-terminal hexahistidine affinity tags were purified by passing the cell lysate through a column of Ni-NTA agarose gel (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The hexahistidine tag was removed by incubation with hexahistidine-tagged recombinant TEV protease and the proteins were further purified by passing the protease reaction products through a second Ni-NTA column, followed by size-exclusion chromatography (Hi-Load 16/600 Superdex™ 200 pg column, GE healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Both proteins were eluted from the column with an elution volume corresponding to Stokes radii consistent with their dimeric forms, and both purified protein solutions separated as a single band on SDS-PAGE.

Spectrophotometric coupled enzymatic assay

Enzyme activity was determined using a FabH-FabG spectrophotometric coupled assay [57]. All of the acyl-CoA variants were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. In all reactions, malonyl-CoA was used as a substrate in place for malonyl-(acyl carrier protein). For screening of possible substrates, the reaction solution with a final volume of 80 μL contains 50 μM acyl-CoA, 200 μM Malonyl-CoA and 150 μM NADPH in a buffer of 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.01% CHAPS and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). Concentrations of all the CoA variants were determined by absorbance at 260 nm with an extinction coefficient of 14,400 M−1 [58], and the concentration of NADPH was determined by absorbance at 340 nm with an extinction coefficient of 6,220 M−1. The reaction was initiated by the addition of a mixture of 2 μg (0.05 nmol) vcFabH and 14 μg (0.5 nmol) vcFabG. The reaction rate for the condensation reaction was monitored by the decrease in absorbance of NADPH at 340 nm upon the reduction of β-ketoacyl-CoA in the presence of an excessive amount of FabG at 30°C in 96-well UV-transmitted half-area microplates (Greiner) using a microplate reader (PHERAstar FS, BMG Labtech). For kinetic assays, the same concentration of malonyl-CoA, NADPH, and FabH/FabG were used, with variable concentrations of octanoyl-CoA (1–80 μM final concentration) for vcFabH2 and acetyl-CoA (1–80 μM final concentration) for vcFabH1. Steady-state reaction velocities (V) were determined as a function of substrate concentration ([S]), in which the substrate was either octanoyl-CoA for vcFabH2 or acetyl-CoA for vcFabH1. Data were fitted to the velocity-based variant of the Hill equation:

| (1.1) |

presuming that the velocity V is proportional to the number of substrate binding sites occupied.

Isothermal titration calorimetric assays for vcFabH2 (C113A) inactive mutant

Acyl-CoA variants (C2–C12, all from Sigma-Aldrich) were used for isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments. ITC measurements were performed at 25°C using an iTC200 microcalorimeter (MicroCal). Proteins were dialyzed against a buffer containing 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 150 mM NaCl. All of the acyl-CoA variants (C2–C12) were dissolved in the same buffer. In each experiment, protein was titrated by either 16 injections of 2.45 μL of ligand solution or 26 injections of 1.5 μL of ligand solution, with 180 s intervals between two titrations. The experiment was performed in high-gain mode with the syringe rotating at 700 rpm. Data processing for ITC experiments was performed using the ORIGIN module of the iTC200 software.

Dynamic Light Scattering assays

Solutions of 2 mg/mL protein or 2mg/mL protein with 5mM of the corresponding ligand in a buffer of 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl was filtered using a 0.10 μm filter before being tested in a Dynapro Titan DLS instrument (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA), which is sensitive to samples with radii in the range of approximately 0.5–500 nm. The measurement of each sample consisted of 3 data acquisitions lasting 300 seconds each. The results were analyzed with DYNAMICS software (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA).

Crystallization, data collection, processing, and structure determination

All crystals were grown by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. The crystallization conditions for each crystal reported here are listed in Table 2. The crystal of vcFabH1 was produced from a buffer of 0.2 M CaCl2, 20% w/v PEG 3350 by using the protein pre-incubated with 5 mM acetyl-CoA. The crystals of vcFabH2 were grown from a buffer of 0.2 M sodium malonate pH 7.0, 16–20% w/v PEG 3350. The crystals were either used as-is or pre-incubated with 5 mM acetyl-CoA/octanoyl-CoA prior to harvesting. Crystals were harvested with the crystallization buffer supplemented with 35% w/v PEG 3350 as cryoprotectant and cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory using beamlines 19-ID and 19-BM of the Structural Biology Center (SBC) as well as beamlines 21-IDG and 21-IDF of the Life Sciences Collaborative Access Team (LS-CAT). Statistics for data collection and structural refinement for each set are listed in Table 2. Data collection, data processing and initial model building were performed with the HKL-3000 program suite [59].

The structure of vcFabH2 was determined by molecular replacement (MR) using the crystal structure of FabH from Aquifex aeolicus VF5 (PDB: 2EBD) as a search model and MOLREP [60] incorporated into HKL-3000. The structure of vcFabH1 was also determined by MR, using the structure of FabH from E. coli (PDB: 1EBL) as a search model. The resulting models were subject to multiple cycles of manual model building with COOT [61] followed by maximum-likelihood refinement with REFMAC5 [62], as incorporated into HKL-3000 [59]. Molprobity [63] and either ADIT (http://deposit.rcsb.org/adit/) or the newer version of the PDB validation server (http://deposit.pdb.org/validate/) were used for structure validation. The atomic coordinates for all structures, along with the corresponding structure factors, were deposited to the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The diffraction images have been deposited to the Integrated Resource for Reproducibility in Macromolecular Crystallography (IRRMC) (http://proteindiffraction.org/) [64]. Statistics describing the quality of the diffraction data and the resultant models are shown in Table 2.

Bioinformatics analyses

The amino acid sequence of vcFabH2 was used to search both the UniProt and the NCBI GenBank non-redundant protein sequence databases using BLASTP [54]. Dali [65] was used to search for structures similar to vcFabH2 in the PDB. Sequence alignment was performed by T-coffee [66] and manipulated in ESPript [67]. PDBePISA was used to calculate the probable oligomeric assemblies, protein-protein interfaces, and related energy changes [36]. Consurf was used to determine the degree of conservation of residues [68]. The volume of the cavities was calculated using 3vee [69]. The primer substrates and their corresponding electron density maps were visualized and analyzed by MOLSTACK [70].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

The molecular dynamics simulation was calculated with Gromacs 5.0 [71]. Forcefield GROMOS43a1 was used for protein atoms, and the SPC/E model [72] for water molecules. The forcefield for octanoyl-CoA was obtained from PRODRG2 Server [73]. The simulation system for vcFabH2 and octanoyl-CoA includes 29,218 water molecules and 26 sodium ions in a cubic box (9.97 nm x 9.97 nm x 9.97 nm). We conducted energy minimization first by employing a steepest descent minimization. Then an NVT (constant number (N), volume (V), and temperature (T)) simulation for 100 ps followed by an NPT (constant number (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T)) simulation for 100 ps were conducted in a periodic boundary condition (PBT). A productive molecular dynamics simulation was also conducted in NPT conditions for 300 ns. All molecular dynamics were conducted at 310 K (36.85 °C) by coupling to the Berendsen thermostat with a coupling time of 0.1 ps [74]. Pressure coupling employs the Parrinello-Rahman method for NPT with tau_p 2.0 ps, 1.0 bar as the reference pressure, and the compressibility 4.5e-5 bar-1 in x, y, and z-directions. During simulation, all bonds were constrained by LINCS [75]. Neighbor searching for short-range electrostatic and van der Waals interactions employed the Verlet cutoff scheme with 1.4 nm as the cutoff. Particle-mesh Ewald summation was used for the long-range electrostatic interactions. During molecular dynamics, we employed 2 fs as the integration time step. We used Gromacs’s g_covar and g_anaeig methods to investigate the 300 ns trajectory of the molecular dynamics of the vcFabH2-octanoyl-CoA complex for deducing the direction and magnitude of the principle motions of vcFabH2. A porcupine plot is prepared with PyMOL [43].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Rachel Ann Vigour and Matthew D. Zimmerman for proofreading the manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Ivan G. Shabalin for help in data collection, and Dr. Igor A. Shumilin for providing valuable discussion in experimental design and critically reading the manuscript. This research was funded by federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services under contract nos. HHSN272200700058C, HHSN272201200026C and HHSN272201700060C and by NIH grant GM117325. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02–06CH11357. The results shown in this report are derived from work performed at beamlines 19ID and 19BM at SBC-CAT and 21ID at LS-CAT. SBC-CAT is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under contract DE-AC02–06CH11357. LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor (Grant 085P1000817). The authors acknowledge Advanced Research Computing Services at the University of Virginia for providing computational resources and technical support that contributed to the results reported within this paper.

Abbreviations:

- ACP

acyl-carrier protein

- ARR

aromatic-ring rich region

- ASU

asymmetric unit

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- FabH

β-ketoacyl-(acyl carrier protein) synthase III

- FAS

fatty acid synthesis

- IRRMC

Integrated Resource for Reproducibility in Macromolecular Crystallography

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

Footnotes

Data availability and accession numbers: Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession numbers 4NHD (vcFabH1, wild-type, soaked with acetyl-CoA), 4WZU (vcFabH2, wild type), 4X0O (vcFabH2, wild type, soaked with acetyl-CoA), 4X9K (vcFabH2, C113A mutant), 4X9O (vcFabH2, C113A mutant, soaked with octanoyl-CoA), 5KP2 (vcFabH2, C113A mutant, soaked with octanoyl-CoA), and 5V0P (vcFabH2, C113A mutant, co-crystallized with octanoyl-CoA) (Table 2). The diffraction images are available on the IRRMC website (http://proteindiffraction.org) with DOIs: 10.18430/M3CC7S, 10.18430/M33W2K, 10.18430/M3V88G, 10.18430/M3JP49, 10.18430/M3PC7K, 10.18430/M35KP2, 10.18430/M35V0P.

Author Contributions

JH conducted experiments and determined the crystal structures. JH and HZ performed structure analysis. WT performed molecular dynamics simulation analysis. HZ and JH drafted the manuscript. HZ coordinated the assembly of data in the project. HZ, DRC, MC, MDC, and WM provided valuable discussion in experimental design, structure determination and refinement. KK performed cloning and initial protein production. MG and HZ provided data management support for the project. WT, DRC, MC, MDC, KK, MG and WM critically read and improved the manuscript. WM supervised the project.

References

- 1.Janson CA, Konstantinidis AK, Lonsdale JT & Qiu X (2000) Crystallization of Escherichia coli beta-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III and the use of a dry flash-cooling technique for data collection. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 56, 747–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith S, Witkowski A & Joshi AK (2003) Structural and functional organization of the animal fatty acid synthase. Prog Lipid Res 42, 289–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao J & Rock CO (2015) How bacterial pathogens eat host lipids: implications for the development of fatty acid synthesis therapeutics. J Biol Chem 290, 5940–5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu XY, Tang J, Zhang Z & Ding K (2015) Bacterial beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) as a target for novel antibacterial agents design. Curr Med Chem 22, 651–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuster M, Sexton DJ, Diggle SP & Greenberg EP (2013) Acyl-homoserine lactone quorum sensing: from evolution to application. Annu Rev Microbiol 67, 43–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez LJ, Ng WL, Marano P, Brook K, Bassler BL & Semmelhack MF (2012) Role of the CAI-1 fatty acid tail in the Vibrio cholerae quorum sensing response. J Med Chem 55, 9669–9681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charles RC & Ryan ET (2011) Cholera in the 21st century. Curr Opin Infect Dis 24, 472–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thapa Shrestha U, Adhikari N, Maharjan R, Banjara MR, Rijal KR, Basnyat SR & Agrawal VP (2015) Multidrug resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 from clinical and environmental samples in Kathmandu city. BMC Infect Dis 15, 104–015–0844–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan JC, Ye R, Wang HQ, Xiang HQ, Zhang W, Yu XF, Meng DM & He ZS (2008) Vibrio cholerae O139 multiple-drug resistance mediated by Yersinia pestis pIP1202-like conjugative plasmids. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52, 3829–3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixit SM, Johura FT, Manandhar S, Sadique A, Rajbhandari RM, Mannan SB, Rashid MU, Islam S, Karmacharya D, Watanabe H, Sack RB, Cravioto A & Alam M (2014) Cholera outbreaks (2012) in three districts of Nepal reveal clonal transmission of multi-drug resistant Vibrio cholerae O1. BMC Infect Dis 14, 392–2334–14–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lennen RM, Braden DJ, West RA, Dumesic JA & Pfleger BF (2010) A process for microbial hydrocarbon synthesis: Overproduction of fatty acids in Escherichia coli and catalytic conversion to alkanes. Biotechnol Bioeng 106, 193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peralta-Yahya PP, Zhang F, del Cardayre SB & Keasling JD (2012) Microbial engineering for the production of advanced biofuels. Nature 488, 320–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang MK & Nielsen J (2017) Biobased production of alkanes and alkenes through metabolic engineering of microorganisms. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 44, 613–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schirmer A, Rude MA, Li X, Popova E & del Cardayre SB (2010) Microbial biosynthesis of alkanes. Science 329, 559–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janssen HJ & Steinbuchel A (2014) Fatty acid synthesis in Escherichia coli and its applications towards the production of fatty acid based biofuels. Biotechnol Biofuels 7, 7–6834–7–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lennen RM & Pfleger BF (2012) Engineering Escherichia coli to synthesize free fatty acids. Trends Biotechnol 30, 659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu X, Choudhry AE, Janson CA, Grooms M, Daines RA, Lonsdale JT & Khandekar SS (2005) Crystal structure and substrate specificity of the beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) from Staphylococcus aureus. Protein Sci 14, 2087–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsay JT, Oh W, Larson TJ, Jackowski S & Rock CO (1992) Isolation and characterization of the beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III gene (fabH) from Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem 267, 6807–6814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou J, Zheng H, Chruszcz M, Zimmerman MD, Shumilin IA, Osinski T, Demas M, Grimshaw S & Minor W (2015) Dissecting the Structural Elements for the Activation of beta-Ketoacyl-(Acyl Carrier Protein) Reductase from Vibrio cholerae. J Bacteriol 198, 463–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khandekar SS, Gentry DR, Van Aller GS, Warren P, Xiang H, Silverman C, Doyle ML, Chambers PA, Konstantinidis AK, Brandt M, Daines RA & Lonsdale JT (2001) Identification, substrate specificity, and inhibition of the Streptococcus pneumoniae beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH). J Biol Chem 276, 30024–30030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanson JD, Himiari Z, Swarbrick CM & Forwood JK (2015) Structural Characterisation of the Beta-Ketoacyl-Acyl Carrier Protein Synthases, FabF and FabH, of Yersinia pestis. Sci Rep 5, 14797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gajiwala KS, Margosiak S, Lu J, Cortez J, Su Y, Nie Z & Appelt K (2009) Crystal structures of bacterial FabH suggest a molecular basis for the substrate specificity of the enzyme. FEBS Lett 583, 2939–2946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies C, Heath RJ, White SW & Rock CO (2000) The 1.8 A crystal structure and active-site architecture of beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) from escherichia coli. Structure 8, 185–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaneda T (1991) Iso- and anteiso-fatty acids in bacteria: biosynthesis, function, and taxonomic significance. Microbiol Rev 55, 288–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira JH, Goh EB, Keasling JD, Beller HR & Adams PD (2012) Structure of FabH and factors affecting the distribution of branched fatty acids in Micrococcus luteus. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68, 1320–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi KH, Heath RJ & Rock CO (2000) beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) is a determining factor in branched-chain fatty acid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol 182, 365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh AK, Zhang YM, Zhu K, Subramanian C, Li Z, Jayaswal RK, Gatto C, Rock CO & Wilkinson BJ (2009) FabH selectivity for anteiso branched-chain fatty acid precursors in low-temperature adaptation in Listeria monocytogenes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 301, 188–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi KH, Kremer L, Besra GS & Rock CO (2000) Identification and substrate specificity of beta -ketoacyl (acyl carrier protein) synthase III (mtFabH) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem 275, 28201–28207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mao YH, Ma JC, Li F, Hu Z & Wang HH (2015) Ralstonia solanacearum RSp0194 Encodes a Novel 3-Keto-Acyl Carrier Protein Synthase III. PLoS One 10, e0136261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan Y, Leeds JA & Meredith TC (2012) Pseudomonas aeruginosa directly shunts beta-oxidation degradation intermediates into de novo fatty acid biosynthesis. J Bacteriol 194, 5185–5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan Y, Sachdeva M, Leeds JA & Meredith TC (2012) Fatty acid biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is initiated by the FabY class of beta-ketoacyl acyl carrier protein synthases. J Bacteriol 194, 5171–5184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heidelberg JF, Eisen JA, Nelson WC, Clayton RA, Gwinn ML, Dodson RJ, Haft DH, Hickey EK, Peterson JD, Umayam L, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Read TD, Tettelin H, Richardson D, Ermolaeva MD, Vamathevan J, Bass S, Qin H, Dragoi I, Sellers P, McDonald L, Utterback T, Fleishmann RD, Nierman WC, White O, Salzberg SL, Smith HO, Colwell RR, Mekalanos JJ, Venter JC & Fraser CM (2000) DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 406, 477–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang W, Jiang Y, Bentley GJ, Liu D, Xiao Y & Zhang F (2015) Enhanced production of branched-chain fatty acids by replacing beta-ketoacyl-(acyl-carrier-protein) synthase III (FabH). Biotechnol Bioeng 112, 1613–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harger M, Zheng L, Moon A, Ager C, An JH, Choe C, Lai YL, Mo B, Zong D, Smith MD, Egbert RG, Mills JH, Baker D, Pultz IS & Siegel JB (2013) Expanding the product profile of a microbial alkane biosynthetic pathway. ACS Synth Biol 2, 59–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Armando JW, Boghigian BA & Pfeifer BA (2012) LC-MS/MS quantification of short-chain acyl-CoA’s in Escherichia coli demonstrates versatile propionyl-CoA synthetase substrate specificity. Lett Appl Microbiol 54, 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krissinel E & Henrick K (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daines RA, Pendrak I, Sham K, Van Aller GS, Konstantinidis AK, Lonsdale JT, Janson CA, Qiu X, Brandt M, Khandekar SS, Silverman C & Head MS (2003) First X-ray cocrystal structure of a bacterial FabH condensing enzyme and a small molecule inhibitor achieved using rational design and homology modeling. J Med Chem 46, 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiu X, Janson CA, Smith WW, Head M, Lonsdale J & Konstantinidis AK (2001) Refined structures of beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III. J Mol Biol 307, 341–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bera AK, Atanasova V, Robinson H, Eisenstein E, Coleman JP, Pesci EC & Parsons JF (2009) Structure of PqsD, a Pseudomonas quinolone signal biosynthetic enzyme, in complex with anthranilate. Biochemistry 48, 8644–8655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goblirsch BR, Frias JA, Wackett LP & Wilmot CM (2012) Crystal structures of Xanthomonas campestris OleA reveal features that promote head-to-head condensation of two long-chain fatty acids. Biochemistry 51, 4138–4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Musayev F, Sachdeva S, Scarsdale JN, Reynolds KA & Wright HT (2005) Crystal structure of a substrate complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) with lauroyl-coenzyme A. J Mol Biol 346, 1313–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sachdeva S, Musayev F, Alhamadsheh MM, Neel Scarsdale J, Tonie Wright H & Reynolds KA (2008) Probing reactivity and substrate specificity of both subunits of the dimeric Mycobacterium tuberculosis FabH using alkyl-CoA disulfide inhibitors and acyl-CoA substrates. Bioorg Chem 36, 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rigsby RE & Parker AB (2016) Using the PyMOL application to reinforce visual understanding of protein structure. Biochem Mol Biol Educ 44, 433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reidl J & Klose KE (2002) Vibrio cholerae and cholera: out of the water and into the host. FEMS Microbiol Rev 26, 125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang YM, Rao MS, Heath RJ, Price AC, Olson AJ, Rock CO & White SW (2001) Identification and analysis of the acyl carrier protein (ACP) docking site on beta-ketoacyl-ACP synthase III. J Biol Chem 276, 8231–8238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vila J, Ruiz J, Gallardo F, Vargas M, Soler L, Figueras MJ & Gascon J (2003) Aeromonas spp. and traveler’s diarrhea: clinical features and antimicrobial resistance. Emerg Infect Dis 9, 552–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Austin B & Zhang XH (2006) Vibrio harveyi: a significant pathogen of marine vertebrates and invertebrates. Lett Appl Microbiol 43, 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gregoret LM, Rader SD, Fletterick RJ & Cohen FE (1991) Hydrogen bonds involving sulfur atoms in proteins. Proteins 9, 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ren J, Wen L, Gao X, Jin C, Xue Y & Yao X (2008) CSS-Palm 2.0: an updated software for palmitoylation sites prediction. Protein Eng Des Sel 21, 639–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nelson EJ, Harris JB, Morris JG Jr, Calderwood SB & Camilli A (2009) Cholera transmission: the host, pathogen and bacteriophage dynamic. Nat Rev Microbiol 7, 693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giles DK, Hankins JV, Guan Z & Trent MS (2011) Remodelling of the Vibrio cholerae membrane by incorporation of exogenous fatty acids from host and aquatic environments. Mol Microbiol 79, 716–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pride AC, Herrera CM, Guan Z, Giles DK & Trent MS (2013) The outer surface lipoprotein VolA mediates utilization of exogenous lipids by Vibrio cholerae. MBio 4, e00305–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]