Abstract

Objective

Mortality statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is used for planning healthcare policy and allocating resources. CDC uses this data to compile its annual leading-causes-of-death ranking based on a selected list of 113 causes. SLE is not included on this list. Since the cause-of-death ranking is a useful tool for assessing the relative burden of cause-specific mortality, we ranked SLE deaths among CDC’s leading causes-of-death to see whether SLE is a significant cause of death among women.

Methods

Death counts were obtained from the CDC’s Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research database in U.S. female population, and then grouped by age and race/ethnicity. Data on the leading causes-of-death were obtained from the Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System database.

Results

During 2000 to 2015, there were 28,411 female deaths with SLE recorded as the underlying or contributing causes of death. SLE ranked among the top 20 leading-causes-of-death in females between 5 and 64 years of age. SLE ranked 10th in the 15–24 years, 14th in the 25–34 and the 35–44 years, and 15th in the 10–14 years age groups. Among black and Hispanic females, SLE ranked 5th in the 15–24 years, 6th in the 25–34 years, and 8th–9th in the 35–44 years age groups, after excluding the three common external injury causes of death from analysis.

Conclusion

SLE is among the leading-causes-of-death in young women, underscoring its impact as an important public health issue.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematous (SLE) is a predominately female, chronic inflammatory disease that can affect virtually any organ. We recently analyzed secular trends and population characteristics associated with SLE mortality using the United States (U.S.) nationwide mortality database comprising of 62,843 SLE deaths, of which 84% were in women (1). We found that although rates of SLE mortality have decreased over the past five decades, SLE mortality rates remain high relative to mortality rate for all causes other than SLE (non-SLE). In fact, the ratio of SLE mortality rate to the mortality rate for non-SLE causes was 34.6% higher in 2013 than in 1968. Thus, SLE mortality remains high in the U.S. population.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s National Vital Statistics System maintains a mortality database, with data provided by various jurisdictions that are legally responsible for the registration of vital events and information extracted from death certificates. This database encompasses more than 99% of deaths of U.S. residents in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Mortality statistics data from this database serve as important indicators of the health of the U.S. population and are used to estimate the burden of specific diseases. Mortality statistics are also used for healthcare policy planning and resource allocation.

Using the National Vital Statistics System mortality database, CDC compiles its annual leading-causes-of-death ranking based on a selected list of 113 causes (2). SLE is not included on this list. The cause-of-death ranking is a useful tool for assessing the relative burden of cause-specific mortality. Hence, we ranked SLE deaths among CDC’s leading causes-of-death to determine the relative burden of SLE deaths in women.

Methods

This is a population-based study using nationwide mortality counts for all female U.S. residents from 2000–2015. Data on SLE deaths were obtained from the CDC Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (CDC WONDER) Multiple Cause-of-Death database (3).

Death certificates in the U.S. provide the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code for the underlying or contributing causes of death (Appendix Figure 1). The underlying cause of death is defined as “the disease or injury that initiated the events resulting in death” (4). The contributing cause of death is defined as “other significant conditions contributing to death but not resulting in the underlying cause”. Deaths were attributed to SLE if an ICD-10 code for SLE (M32 [SLE], M32.1 [SLE with organ or system involvement], M32.8 [other forms of SLE], and M32.9 [SLE, unspecified]) was listed as the underlying or contributing causes of death on the death certificates.

Age, race, and ethnicity were ascertained using standard methods described in the Technical Appendix, Vital Statistics (5). Race is classified as white, black or African-American, Asian or Pacific Islander, and American Indian or Alaska Native. Ethnicity is classified as Hispanic or Non-Hispanic.

Death counts were obtained, using WONDER, in female U.S. population by age groups and race/ethnicity.

Data on the leading causes-of-death were obtained from the CDC WONDER Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) database (3).

Results

During 2000–2015, there were a total of 28,411 deaths in females with SLE recorded as the underlying or a contributing cause of death. The largest number of SLE deaths was in the 65+ years age group (Table 1). There were 8 SLE deaths in the 0–4 years age group, 18 in the 5–9 years, and 78 in the 10–14 years age group.

Table 1.

Twenty leading causes of death in females in the United States from 2000 to 2015.

| 5–9 year * | 10–14 year | 15–24 year | 25–34 year | 35–44 year | 45–54 year | 55–64 year | 65+ year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | ||||||||

| 1 | Unintentional Injury † 6,052 |

Unintentional Injury 6,438 |

Unintentional Injury 56,747 |

Unintentional Injury 57,741 |

Malignant Neoplasms 121,604 |

Malignant Neoplasms 387,239 |

Malignant Neoplasms 747,302 |

Heart Diseases 4,468,532 |

| 2 | Malignant Neoplasms 3,415 |

Malignant Neoplasms 3,450 |

Suicide 12,328 |

Malignant Neoplasms 30,101 |

Unintentional Injury 75,614 |

Heart Diseases 166,833 |

Heart Diseases 334,259 |

Malignant Neoplasms 3,046,099 |

| 3 | Congenital Anomalies 1,420 |

Suicide 1,390 |

Homicide 10,746 |

Suicide 17,021 |

Heart Diseases 57,325 |

Unintentional Injury 91,853 |

Chronic Lower Resp Disease 104,733 |

Cerebrovascular 1,224,648 |

| 4 | Homicide 948 |

Congenital Anomalies 1,302 |

Malignant Neoplasms 10,454 |

Heart Diseases 16,951 |

Suicide 24,778 |

Cerebrovascular 42,810 |

Diabetes Mellitus 75,872 |

Chronic Lower Resp Disease 978,817 |

| 5 | Heart Diseases 726 |

Homicide 1,033 |

Heart Disease 5,534 |

Homicide 12,047 |

Cerebrovascular 15,801 |

Liver Diseases 38,999 |

Cerebrovascular 73,651 |

Alzheimer’s Disease 844,609 |

| 6 | Influenza & Pneumonia 408 |

Heart Diseases 951 |

Congenital Anomalies 2,820 |

HIV 6,543 |

HIV 15,224 |

Diabetes Mellitus 35,350 |

Unintentional Injury 63,404 |

Diabetes Mellitus 454,459 |

| 7 | Chronic Lower Resp Disease 337 |

Chronic Lower Resp Disease 451 |

Complicated Pregnancy 2,502 |

Complicated Pregnancy 5,193 |

Liver Disease 14,919 |

Chronic Lower Resp Dis 33,297 |

Liver Disease 41,614 |

Influenza & Pneumonia 448,129 |

| 8 | Benign Neoplasms 333 |

Influenza & Pneumonia 420 |

Influenza & Pneumonia 1,358 |

Diabetes Mellitus 4,329 |

Diabetes Mellitus 12,094 |

Suicide 30,842 |

Septicemia 32,722 |

Unintentional Injury 317,971 |

| 9 | Cerebrovascular 299 |

Cerebrovascular 339 |

Cerebrovascular 1,357 |

Cerebrovascular 4,097 |

Homicide 11,450 |

Septicemia 17,072 |

Nephritis 31,003 |

Nephritis 314,704 |

| 10 | Septicemia 250 |

Benign Neoplasms 297 |

SLE 1,226 |

Congenital Anomalies 2,897 |

Chronic Lower Resp Disease 6,948 |

Influenza & Pneumonia 14,323 |

Influenza & Pneumonia 24,855 |

Septicemia 243,733 |

| Diabetes Mellitus 1,176 | ||||||||

| 11 | Anemias 136 |

Septicemia 260 |

HIV 1,060 |

Influenza & Pneumonia 2,888 |

Septicemia 6,671 |

HIV 13,935 |

Suicide 20,156 |

Hypertension 216,273 |

| 12 | Perinatal Period 122 |

Diabetes Mellitus 180 |

Septicemia 1,023 |

Liver Disease 2,674 |

Influenza & Pneumonia 6,505 |

Nephritis 13,665 |

Hypertension 15,010 |

Parkinson’s Disease 136,101 |

| 13 | Meningitis 66 |

Anemias 158 |

Chronic Lower Resp Disease 1,012 |

Septicemia 2,510 |

Nephritis 5,109 |

Viral Hepatitis 10,129 |

Viral Hepatitis 11,449 |

Pneumonitis 122,080 |

| 14 | Nephritis 66 |

Perinatal Period 98 |

Anemias 695 |

SLE 2,431 |

SLE 3,646 |

Homicide 8,462 |

Benign Neoplasms 9,587 |

Benign Neoplasms 93,021 |

| Chronic Lower Resp Disease 2,000 |

Congenital Anomalies 3,502 |

|||||||

| 15 | Diabetes Mellitus 56 |

SLE 78 |

Nephritis 619 |

Nephritis 1,932 |

Complicated Pregnancy 3,421 |

Hypertension 7,302 |

Alzheimer’s Disease 6,283 |

Atherosclerosis 89,423 |

| HIV 77 | ||||||||

| 16 | Pneumonitis 33 |

Meningitis 74 |

Benign Neoplasms 614 |

Anemias 1,149 |

Viral Hepatitis 2,499 |

SLE 5,271 |

Pneumonitis 5,867 |

Liver Diseases 76,262 |

| Benign Neoplasms 5,156 | ||||||||

| 17 | Diseases of Appendix 32 |

Nephritis 72 |

Pneumonitis 250 |

Benign Neoplasms 1,100 |

Benign Neoplasms 2,343 |

Congenital Anomalies 5,134 |

Congenital Anomalies 5,860 |

Aortic Aneurysm 69,881 |

| 18 | Meningococcal Infection 30 |

Pneumonitis 41 |

Liver Diseases 188 |

Hypertension 673 |

Hypertension 2,314 |

Pneumonitis 2,923 |

HIV 5,804 |

Anemias 36,608 |

| 19 | HIV 29 |

Meningococcal Infection 35 |

Meningitis 186 |

Pneumonitis 483 |

Anemias 1,548 |

Aortic Aneurysm 2,706 |

Aortic Aneurysm 5,610 |

Nutritional Deficiencies 31,075 |

| 20 |

SLE 18 |

Diseases of Appendix 33 |

Meningococcal Infection 157 |

Aortic Aneurysm 416 |

Pneumonitis 1,103 |

Anemias 2,119 |

SLE 5,495 |

Gallbladder Disorders 24,676 |

|

|

Homicide 4,430 |

|||||||

| 20+ |

SLE 10,238 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immune deficiency virus disease; Resp, Respiratory.

There were 8 SLE deaths in 0–4-year age group (not shown in the table).

External injury causes of death, including unintentional injury, homicide, and suicide, are represented in the gray font. SLE is shown in the shaded cells.

The ranking of SLE deaths relative to the official 20 leading causes of death in females is displayed in Table 1. SLE is among the top 20 leading causes of death in females between 5 and 64 years of age. SLE ranked 10th in the 15–24 years age group, 14th in the 25–34 and the 35–44 years age groups, and 15th in the 10–14-year age group. In the 15–24 years age group, SLE is the #1 single chronic inflammatory disease, ranking higher than diabetes mellitus, human immune deficiency virus disease, chronic lower respiratory disease, nephritis, pneumonitis, and liver diseases.

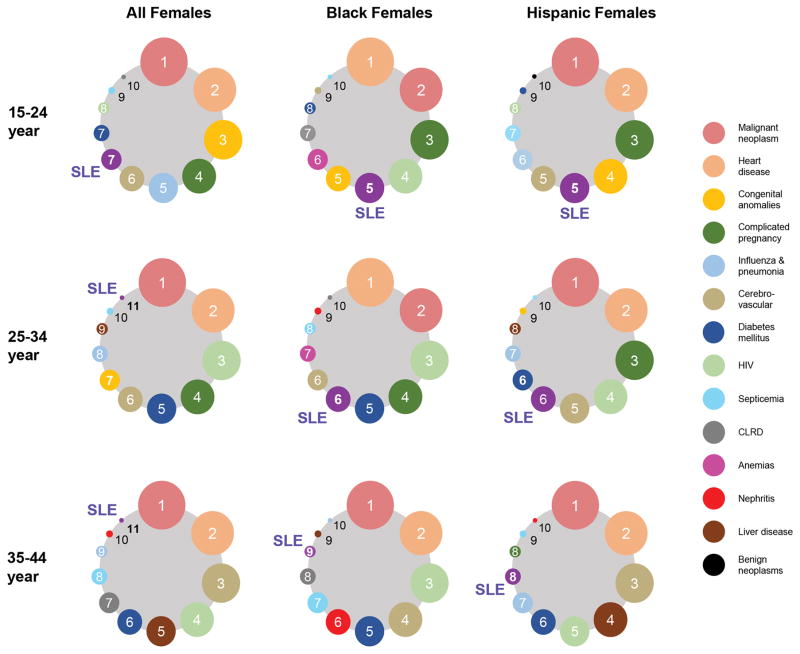

Since SLE mortality rate is independently associated with female gender and non-White races (1), we assessed the relative burden of SLE mortality in minority women of reproductive age (Figure 1). To focus on the organic causes of death, three common external injury causes of death, namely unintentional injury, homicide, and suicide, were excluded from this analysis. For females of all race/ethnicity, SLE ranked 7th as the leading cause of death in the 15–24 years age group and 11th in both the 25–34 and 35–44 years age groups. Among Black and Hispanic females, the rankings for SLE were higher: 5th in the 15–24 years age group, 6th in the 25–34 years age group, and 8th–9th in the 35–44 years age group.

Figure 1. Leading Causes of Deaths for Females of Reproductive Age by Race/Ethnicity and Age.

The ranking of SLE relative to the official 10 leading causes of death in women of reproductive age in the United States from 2000–2015 is displayed. SLE deaths include cases where SLE was listed as the underlying or contributing cause of death using ICD-10 code M32 (all deaths since 1999 have been coded using ICD-10). To focus on the organic causes of death, we excluded the external injury causes of death, namely unintentional injury, homicide, and suicide, from this analysis. Ranking is shown for women of all races (left panels), non-Hispanic Black (middle), and Hispanic women (right) in 15–24-year (top), 25–34-year (middle), and 35–44-year (bottom) age groups. ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

Discussion

This study illustrates that SLE is among the leading causes of death in young women. The actual rankings for SLE would likely be even higher, because SLE may not be recorded on the death certificates in as many as 40% of patients with SLE in the U.S. (6). Furthermore, the ranking for some other leading causes of death may be higher than their actual rank, for example, death certificates tend to overestimate cardiovascular disease mortality (7). The underreporting of SLE on the death certificates may occur, because patients with SLE die prematurely of complications such as cardiovascular events, infections, renal failure, and respiratory diseases (8). These proximate causes of death may be perceived to be unrelated to SLE, when in fact the disease or the medications used for it predispose to them. At the time of death many SLE patients may be under care of physicians who may have a limited awareness of SLE as the underlying cause of death. For example, 86% of 2,314 SLE deaths in Sweden occurred in hospital units other than rheumatology (9). Thus, many SLE patients may only have the proximate causes of death, and not SLE, recorded on their death certificates. Understanding the burden of SLE deaths will help improve this knowledge gap in healthcare workers. An awareness campaign to educate primary care physicians and internists about the multi-organ complications of SLE and its varying presentations at the time of death may be helpful in future studies to assess the true burden of SLE mortality.

We recently reported the multiple regression analysis of SLE mortality risk stratified by race/ethnicity (1). This showed that SLE mortality risk was higher in females than in males in all race/ethnic groups, but both the adjusted odds ratio and predicted annual mortality differences were largest in black persons followed by Hispanics. The adjusted odds ratios for females relative to males were 6.49 (95% CI, 6.02 to 7.00) in black persons, 5.81 (95% CI, 5.19 to 6.51) in Hispanics, and 4.62 (95% CI, 4.37 to 4.88) in white persons. Consistently, SLE ranked higher among the leading causes of death in non-white women. Our data likely underestimate the true disease burden in minorities, given the under-ascertainment and under-recording of SLE deaths in less-well educated ethnic minorities (10) and uninsured patients (6). The higher rankings for SLE deaths in minority women are unlikely to be artifacts from misclassification of cause of death, because greater underreporting of SLE as the cause of death in underprivileged groups (6, 10) would lead to greater underestimation of SLE deaths in the groups we found the ranking to be higher, namely black persons and Hispanics. The difficulty in ascertaining the accuracy of the physicians’ coding on death certificates still remains an important limitation of this study. Though, it is less likely that SLE would be recorded as a cause of death on death certificates of the deceased who did not have SLE.

Several studies have suggested that older age is associated with lack of recording of SLE in death certificates. In the LUMINA (Lupus in Minorities: Nature vs Nurture) and Carolina Lupus Study cohorts, the age at death was significantly higher among those for whom SLE was omitted on the death certificates compared to those who had SLE included in death certificates (mean ± S.D., 50.9±15.6 versus 39.1±18.6; P = 0.005; n = total 76 SLE deaths) (6). The age at death was also significantly higher for SLE decedents who did not have SLE recorded on the death certificates compared to those who had (mean ± S.D., 55.5±16.4 versus 44.4±17.6; P <0.0001; n = 321 SLE deaths) in the Georgia Lupus Registry (11). In a Swedish population-based study that included 1,802 SLE deaths, decedents 60–79 years old at death were approximately 2.5 times as likely to have SLE missing from their death certificates compared with those <40 years (odds ratio: 2.48, 95% CI: 1.34–4.58) (12). These studies also found that SLE patients dying of cancer or a cardiovascular event were more likely to be in the non-recorded group (6, 12). Thus, the lower placement of SLE in the leading-causes-of-death ranking list in older age groups may be due to omission of SLE on death certificates of SLE decedents whose proximate causes of death were cancer and cardiovascular events.

Our findings underscore SLE as an important public health issue in young women, which should be addressed by targeted public health and research programs. Increasing awareness among pediatricians and primary care physicians about the importance of early diagnosis and better management of SLE may help to reduce the high burden of SLE mortality. In recognition of the high mortality of SLE, the National Institutes of Health in 2015 increased funding for SLE to 90 million research dollars annually. This is in comparison to 1,010 million for diabetes mellitus and 3,166 million dollars for human immune deficiency virus disease. In light of our data showing a higher burden of SLE mortality in younger women than previously perceived, further increases in research funding for SLE is warranted.

In conclusion, the inclusion of SLE in CDC’s selected list of causes of death for their annual ranking would highlight the importance of this disease as a major cause of death among young women. The recognition of SLE as a leading cause of death may influence physicians’ coding on death certificates, CDC reporting of death burden, government policy, and government research funding, which may eventually help in reducing the disease burden of SLE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: EY was supported by NIH T32-DK-07789 and UCLA Children’s Discovery and Innovation Institute. RRS was supported by NIH R01 AR056465, Lupus Foundation of America, and Rheumatology Research Foundation.

We sincerely thank Dr. Jennifer Grossman for critically reading the manuscript.

References

- 1.Yen EY, Shaheen M, Woo JMP, Mercer N, Li N, McCurdy DK, et al. 46-Year Trends in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Mortality in the United States, 1968 to 2013: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(11):777–85. doi: 10.7326/M17-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed Februray 6, 2017];Deaths: leading causes for 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_05.pdf.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed January 15, 2017];WONDER Online Databases. https://wonder.cdc.gov/

- 4.ICD-10 Mortality Manual 2a. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. Section I - Instructions for classifying the underlying cause of death. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Technical Appendix. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; [on October 1, 2015]. Vital statistics of the United States: Mortality. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/statab/techap99.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvo-Alen J, Alarcon GS, Campbell R, Jr, Fernandez M, Reveille JD, Cooper GS. Lack of recording of systemic lupus erythematosus in the death certificates of lupus patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44(9):1186–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coady SA, Sorlie PD, Cooper LS, Folsom AR, Rosamond WD, Conwill DE. Validation of death certificate diagnosis for coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(1):40–50. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas G, Mancini J, Jourde-Chiche N, Sarlon G, Amoura Z, Harle JR, et al. Mortality associated with systemic lupus erythematosus in France assessed by multiple-cause-of-death analysis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2503–11. doi: 10.1002/art.38731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjornadal L, Yin L, Granath F, Klareskog L, Ekbom A. Cardiovascular disease a hazard despite improved prognosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a Swedish population based study 1964–95. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(4):713–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward MM. Education level and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): evidence of underascertainment of deaths due to SLE in ethnic minorities with low education levels. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(4):616–24. doi: 10.1002/art.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaysen K, Drenkard C, Bao G, Lim SS. Death Certificates Do Not Accurately Identify SLE Patients [abstract] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(suppl 10) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falasinnu T, Rossides M, Chaichian Y, Simard JF. Do Death Certificates Underestimate the Burden of Rare Diseases: The Example of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Mortality in Sweden [abstract] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(suppl 10) doi: 10.1177/0033354918777253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.