Abstract

Recent epidemiological studies have revealed significant positive associations between exposure to organochlorine (OC) pesticides and occurrence of the metabolic syndrome and there are a growing number of animal based studies to support causality. However, the cellular mechanisms linking OC compound exposure and metabolic dysfunction remain elusive. Therefore, the present study was designed to determine if direct exposure to three highly implicated OC compounds promoted hepatic steatosis, the hepatic ramification of the metabolic syndrome. First, the steatotic effect of p,p′-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), oxychlordane, and trans-nonachlor was determined in freshly isolated rat primary hepatocytes. Exposure to trans-nonachlor significantly increased neutral lipid accumulation as opposed to DDE and oxychlordane. To determine possible mechanisms governing increased fatty acid availability, the effects of trans-nonachlor exposure on fatty acid uptake, de novo lipogenesis, triglyceride secretion, and fatty acid oxidation were explored. Trans-nonachlor did not significantly alter fatty acid uptake. However, insulin-stimulated de novo lipogenesis as well as basal expression of fatty acid synthase, a major regulator of lipogenesis were significantly increased following trans-nonachlor exposure. Interestingly, there was a significant decrease in fatty acid oxidation following trans-nonachlor exposure. This decrease in fatty acid oxidation was accompanied by a slight, but significant increase in oleic acid-induced cellular triglyceride secretion. Therefore, taken together, the present data indicate direct exposure to trans-nonachlor has a more potent pro-steatotic effect than exposure to DDE or oxychlordane. This pro-steatotic effect of trans-nonachlor appears to be predominately mediated via increased de novo lipogenesis and decreased fatty acid oxidation.

Keywords: Trans-nonachlor, hepatic steatosis, primary hepatocyte, de novo lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation

1. Introduction

The metabolic syndrome is a highly prevalent state of metabolic dysfunction that affects approximately 35% of adults in the United States (U.S.) and is a significant risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease.1 A clustering of three out of five of the following metabolic risk factors: increased waist circumference, hypertriglyceridemia, decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, hyperglycemia, and hypertension is diagnostic of metabolic syndrome. Although the development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is not part of the diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome, it is intimately associated with this syndrome and is widely considered to be the hepatic component of metabolic syndrome.2–4 Research has revealed hepatic steatosis is the precursor of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is characterized by increased hepatic inflammation in addition to hepatocyte neutral lipid accumulation.5,6

Until recently, an environmental exposures component to the pathogenesis of NAFLD and possible progression to NASH has been largely unexplored. However, recent epidemiological studies indicate exposure to certain persistent organic pollutants (POPs), including the organochlorine (OC) insecticides or their metabolites and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) can promote metabolic dysfunction such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD [for reviews see 7,8]. These epidemiological studies are reinforced by in vivo rodent studies illustrating consumption of POPs-contaminated salmon oil in conjunction with a high fat diet (HFD) or a high fat/high carbohydrate western diet (WD) exacerbated diet-induced metabolic dysfunction.9,10 Other in vivo rodent studies have demonstrated exposure to PCBs alone or in conjunction with consumption of an HFD can exacerbate diet-induced metabolic dysfunction.11–13 Thus, interaction with high dietary fat content may mediate POPs-induced metabolic dysfunction. However, recent studies from Mulligan et al. (2017) indicate that exposure to a defined mixture of OC pesticides and PCBs promotes hepatic steatosis in the ob/ob mouse.14 Although these studies demonstrate a causal relationship, the cellular mechanisms governing POPs-mediated alterations in metabolic function are not well established.

Exposure to POPs typically consists of exposure to a mixture of compounds, the relative contribution of individual POPs which comprise these mixtures to the promotion of alterations in hepatic lipid metabolism is not well known. Recent studies by Ward et al. (2016) demonstrated exposure to DDE, a highly prevalent POP, exacerbates fatty acid-induced apolipoprotein B (APOB) secretion while decreasing neutral lipid accumulation in a hepatoma model of liver function.15 In addition, Liu et al. (2017) demonstrated increased lipid accumulation following exposure to DDE and β-hexachlorohexane (β-HCH) in human HepG2 cells.16 Thus, these recent studies indicate POPs exposure can have a direct effect on the hepatocyte to alter hepatic lipid metabolism. Therefore, the present study was designed to determine the relative steatotic potential of three highly implicated OC pesticides or their metabolites, DDE, oxychlordane, and trans-nonachlor, and to examine the alterations in hepatic lipid metabolism which may govern OC-induced steatosis. Specifically, alterations in fatty acid uptake/accumulation, de novo lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation/degradation, and fatty acid secretion as triglyceride laden very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) were explored as key mediators of hepatic lipid metabolism which may be altered following OC exposure to promote NAFLD. We utilized freshly isolated rat primary hepatocytes as an “ex vivo” model of liver function to examine direct effects of OC exposure on hepatocyte function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Reagents

The OC compounds trans-nonachlor and oxychlordane were obtained from AccuStandard, Inc. and DDE was obtained from ChemService. Each OC compound was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at a 4000× concentration to produce a final DMSO concentration of 0.025% in cell culture treatments. Cell culture media (RPMI-1640) and related components including sodium pyruvate, glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, insulin, and fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin were obtaining from Sigma-Aldrich. Oil Red O (ORO) and Janus Green (JG) stains were obtaining from Sigma-Aldrich and a stock solution of ORO (3 mg/ml) was made in 100% isopropanol. 4,4-difluoro-5-methyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-dodecanoic acid (BODIPY 500/510 C12; BODIPY-FA) for use in extracellular free fatty acid uptake assays was obtained from Life Technologies (ThermoFisher Scientific). Radiolabeled 14C-acetate for de novo lipogenesis assays was purchased from Perkin Elmer. Triglyceride and β-hydroxybutyrate assay kits were purchased from Cayman Chemical.

2.2 Animal Care and Use

Male Sprague Dawley rats (200–225 g) were purchased from Envigo (East Millstone, NJ) and allowed to acclimate for at least one week prior to any experimental manipulations. Animals were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC) approved animal facility in the Mississippi State University (MSU) College of Veterinary Medicine and were allowed access to standard rodent chow and water ad libitum. All laboratory animal use protocols were approved by the MSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) prior to animal usage.

2.3 Primary hepatocyte isolation and culture

Rat primary hepatocytes were isolated via collagenase perfusion and subsequent centrifugation as previously performed.17,18 Briefly, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and the abdomen incised at the midline to visualize the hepatic portal vein. Following portal vein isolation, a plastic cannula was inserted into the portal vein and the liver perfused with approximately 50 ml of Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS; without calcium or magnesium; with 5.5 mM glucose; pH 7.4). Following perfusion with HBSS, livers were perfused with collagenase (0.05% in HBSS at 37°C) for 20 minutes. Following collagenase perfusion, livers were removed, minced, and incubated at 37°C with shaking to liberate hepatocytes from liver capsule. Hepatocyte suspensions were sequentially filtered through 100 μm and 70 μm nylon filters then centrifuged three times at 100xg for 1 minute per centrifugation. The parenchymal hepatocyte fraction was then resuspended and cell viability measured by trypan blue exclusion. Isolations with greater than 75% viability were utilized for subsequent experiments. Primary hepatocytes were plated on rat tail collagen type 1 coated cell culture plates at 1×106 cells/ml in normal growth media (RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS, sodium pyruvate, glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin) with 10 μg/ml insulin for 3–4 hours for attachment. Following attachment, cells were washed with PBS then incubated in either normal growth media to examine effects of OC exposure on neutral lipid accumulation under normal growth conditions or serum free growth media with FBS being replaced by fatty acid free BSA (0.5%) overnight to examine the effects of OC exposure on fatty acid uptake, lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, and fatty acid secretion without confounding effects of hormones or fatty acids which are present in FBS.

2.4 Intracellular neutral lipid accumulation

The effects of the OC compounds trans-nonachlor, oxychlordane, and DDE were determined in rat primary hepatocytes by ORO staining following exposure as previously performed in other cell types.19,20 To determine the concentration and time-dependent effect of OC exposure, rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to either trans-nonachlor, oxychlordane, or DDE (0, 0.02, 0.2, 2.0, 20, or 80 μM) for 24 or 48 hours in normal growth media with duplicate measurements per individual hepatocyte isolation. Following exposure, hepatocytes were washed once with PBS the fixed with 10% buffered formalin for at least 30 minutes prior to ORO staining to measure intracellular neutral lipid accumulation. Intracellular triglyceride levels were measured via commercially available assay (Cayman Chemical) per manufacturer’s instructions and expressed as μmole TG/mg protein as previously performed to confirm that significant ORO accumulation is due to increased intracellular triglyceride accumulation.19

2.5 Oil Red O staining

Following formalin fixation, cell monolayers were washed with PBS then subjected to ORO staining as previously performed in our lab.19,20 Briefly, cell monolayers were incubated with 60% isopropanol for 10 minutes then stained with ORO working solution (60% ORO stock solution, 40% deionized water) for 15 minutes. Following ORO staining, cell monolayers were washed six times with deionized water then allowed to air dry overnight. Once completely dry, ORO stain was extracted from the cell monolayer with 100% isopropanol and the absorbance measured at 520 nm to determine the amount of intracellular neutral lipid. Cell monolayers were then washed with deionized water and stained with JG as an index of total cell count. JG stain was extracted with 0.5 N HCl and absorbance measured at 595 nm. Data are expressed as the ratio of ORO absorbance to JG absorbance (ORO/JG) to normalize for potential alterations in cell number following exposure. ORO stained cells were visualized by light microscopy and digital images of vehicle and trans-nonachlor (20 μM) treated cells captured at 400× magnification.

2.6 Extracellular free fatty acid uptake/accumulation

The effect of trans-nonachlor on free fatty acid uptake/accumulation was determined using Bodipy-labeled 4,4-difluoro-5-methyl-4-bora-3a,4a-diaza-s-indacene-3-dodecanoic acid (BODIPY 500/510 C12; BODIPY-FA; Molecular Probes) as previously described.19 Briefly, primary hepatocytes were treated with vehicle (DMSO 0.025%) or trans-nonachlor (0.2, 2, or 20 μM) for 24 hours in serum free RPMI-1640 containing fatty acid free BSA (0.5%) with duplicate measurements per individual hepatocyte isolation. Following trans-nonachlor treatment, cells were washed with PBS then exposed to Bodipy-labeled dodecanoic acid for 1 minute and 60 minutes to assess saturable, transporter mediated fatty acid uptake and fatty acid accumulation, respectively.19 At the end of Bodipy-labeled dodecanoic acid exposure, cells were washed three times with ice cold PBS then homogenized in 0.2% SDS. Cellular homogenate fluorescence intensity was measured at an excitation of 490 nm and an emission of 528 nm. Homogenate protein concentration was determined via Bradford assay and data expressed as the homogenate RFU per μg of protein.

2.7 De novo lipogenesis assay

The effects of exposure to trans-nonachlor on primary hepatocyte de novo lipogenesis was determined via 14C-acetate incorporation into cellular lipids as previously described with minor modifications.19 Primary hepatocytes were exposed to either vehicle (DMSO 0.025%) or trans-nonachlor (0.2, 2, or 20 μM) in serum free RPMI-1640 media for 24 hours with or without insulin stimulation for the final 8 hours of exposure. Duplicate measurements were performed on each individual hepatocyte isolation. At the end of 24 hours, 2 μCi/ml of 14C-acetate was spiked into the media and incubated at 37°C for 3 hours. Following 14C-acetate exposure, cell monolayers were washed three times with ice cold PBS then scraped in 200 μl of PBS. Total lipid fractions of the cell suspension were extracted in 1 ml of 3:2 hexane to isopropanol then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes to separate organic and aqueous phases. The top organic phase (500 μl/sample) was added to liquid scintillation counting fluid (3.5 ml; Optima Gold) then radioactivity determined by liquid scintillation counter. Data are expressed as the counts per minute (cpm)/mg of cellular lysate. Radioactivity in the total lipid fraction was used to determine cellular lipogenesis as previously performed based on our previous studies demonstrating the majority of 14C-acetate incorporation into cellular lipids is partitioned to the triglyceride fraction.18

2.8 Fatty acid oxidation

Cellular β-hydroxybutyrate (β-HB) levels were measured to determine potential effects on cellular fatty acid oxidation due to the fact the β-HB is a major product of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation and is widely utilized as a systemic biomarker of fatty acid oxidation. To examine potential effects on fatty acid oxidation, primary hepatocytes were treated with vehicle (DMSO 0.025%) or trans-nonachlor (0.2 and 20 μM) for 24 hours in serum free RPMI-1640 media with the addition of either fatty acid free BSA (0.5%) or oleic acid (OA; 400 μM) for the last 8 hours of exposure. Duplicate measurements were performed on each hepatocyte isolation. At the end of 24 hours, cells were washed with PBS, lysates made in assay buffer, then cellular levels of β-HB measured per the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemical). Data are expressed as μmole/mg cellular protein.

2.9 Cellular triglyceride/VLDL secretion

Cellular triglyceride efflux was measured as an index of triglyceride laden VLDL secretion as previously performed.19 Primary hepatocytes were treated with vehicle or transnonachlor as described in section 2.8 for assessment of fatty acid oxidation. Following exposure, cell culture media (500 μl) was extracted via the Folch method to isolate the lipid constituents and the lipid containing organic phase was dried via speed-vac.21 Dried lipids were resuspended in 100 μl methanol and triglyceride levels were measured via commercially available assay per the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemical). Data are expressed as media μmole TG/mg cellular protein for normalization.

2.10 Lipid peroxidation and cellular glutathione levels

Cellular lipid peroxidation and glutathione levels were determined to assess cellular oxidative stress status as previously described.19 Briefly, following exposure to vehicle (DMSO 0.025%) or trans-nonachlor (0.2 and 20 μM) for 24 hours in normal growth media, the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay was utilized to measure cellular levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), a widely used indicator of oxidative stress. Cellular levels of glutathione were measured as an index of cellular anti-oxidant capacity via the manufacturer’s protocol (Cayman Chemical). Duplicate measurements were performed on each hepatocyte isolation. Data were expressed as nmole MDA/mg protein for the TBARS assay and μg glutathione/mg protein.

2.11 SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

Following exposure for either de novo lipogenesis assay or triglyceride secretion, cellular homogenate proteins (25–50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE on either 7.5% gels for lipogenic proteins or 4–15% gels for APOB. Following separation, proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and incubated with primary antibodies directed against fatty acid synthase (FAS; cat# sc-55580; Santa Cruz Biotech), sterol response element binding protein-1 (SREBP1; cat# ab3259; Abcam), APOB (cat# NB200-527; Novus Biologicals), or β-actin (Actin; cat# sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotech) then HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Proteins were visualized by chemiluminescence, digital images captured with a Chemidoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad), and band integrated density measured via ImageJ analysis software (NIH). Data are expressed as the ratio of FAS, SREBP1c, or APOB integrated densities to Actin.

2.12 Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) for each experimental group with individual animal duplicate measurements being averaged together and the average representing the individual animal value within each experimental group. For experiments with more than two groups, data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons (SigmaPlot 13). For experiments with two separate treatments, such as trans-nonachlor with or without OA, a two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s post host test for pairwise comparison. For experiments with two groups, a Student’s t-test was utilized for between group comparisons. The threshold of statistical significance was a P-value ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Exposure to trans-nonachlor increases intracellular neutral lipid accumulation

The steatotic potential of trans-nonachlor, oxychlordane, and DDE was determined in rat primary hepatocytes following exposure for 24 or 48 hours. Exposure to trans-nonachlor (20 and 80 μM; 0.576 ± 0.046 and 0.593 ± 0.032 ORO/JG, respectively) significantly increased ORO staining by 37% and 41% compared to vehicle (0.42 ± 0.036 ORO/JG) following exposure for 24 hours (Figure 1C). While both oxychlordane and DDE tended to increase ORO accumulation following 24 hours of exposure, these effects were not statistically significant. Visual analysis confirmed increased ORO staining in lipid droplets of trans-nonachlor-treated cells (20 μM; Figure 1B) compared to vehicle-treated cells (Figure 1A). Increased ORO staining was associated with increased cellular triglyceride concentrations following exposure to trans-nonachlor (20 μM) for 24 hours (Figure 1D) compared to vehicle.

Figure 1.

Exposure to trans-nonachlor but not oxychlordane or DDE significantly increases hepatocyte neutral lipid accumulation. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to DDE, oxychlordane, or trans-nonachlor for 24 hours or 48 hours then subjected to either ORO staining (C and E) or intracellular triglyceride measurement (D and F) to assess intracellular neutral lipid levels. Representative microphotographs (400× magnification) demonstrate ORO staining in vehicle (A) or trans-nonachlor (B) treated cells following 24 hours of exposure. Data represent the mean ± SEM for n=5–6 animals/group for ORO staining and n=4 animals/group for triglyceride measurement. *P≤0.05 vs. vehicle (0 μM)

The pro-steatotic effects of trans-nonachlor (20 and 80 μM; 0.691 ± 0.025 and 0.705 ± 0.051 ORO/JG, respectively) were maintained following 48 hours of exposure with increases in ORO accumulation by 24% and 27% compared to vehicle (Figure 1E; 0.557 ± 0.021 ORO/JG). This increase in ORO staining was associated with a significant increase in intracellular triglyceride accumulation following exposure to trans-nonachlor (20 μM) compared to vehicle (Figure 1F). Therefore, exposure to trans-nonachlor (20 and 80 μM) for 24 and 48 hours elicited a pro-steatotic response with trans-nonachlor being more pro-steatotic than both oxychlordane and DDE, which had no significant pro-steatotic effects at 24 or 48 hours. Given trans-nonachlor appears to be more pro-steatotic than either oxychlordane or DDE, trans-nonachlor-induced alterations in hepatic lipid metabolism which could promote steatosis were explored in subsequent experiments. It should be noted that cytotoxicity was measured by cell viability reagent (Cell Counting Kit-8; Sigma-Aldrich) as previously performed and there was no observed cytotoxicity (data not shown) at the currently utilized concentrations.19

3.2 Trans-nonachlor does not significantly increase Bodipy-labeled extracellular fatty acid uptake/accumulation

Extracellular free fatty acid uptake is the primary source of free fatty acids for esterification into triglycerides in NAFLD.4 Therefore, the effects of trans-nonachlor on Bodipy-labelled dodecanoic acid were determined following exposure for 24 hours (Figure 2). As anticipated based on previous studies in our lab, incubation with Bodipy-labelled dodecanoic acid significantly increased in all treatment groups following 60 minutes of exposure compared to 1 minute of exposure.19 While exposure to trans-nonachlor (0.2, 2, and 20 μM) tended to increase Bodipy-labelled fatty acid accumulation, these increases were not statistically significant compared to corresponding time-matched vehicle treated levels. Thus, exposure to trans-nonachlor does not significantly increase Bodipy-labelled dodecanoic acid indicating increased extracellular fatty acid uptake does not mediate trans-nonachlor-induced neutral lipid accumulation.

Figure 2.

Effect of trans-nonachlor on uptake and accumulation of Bodipy-labeled dodecanoic acid. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours then treated with Bodipy-labeled dodecanoic acid for 1 minute or 60 minutes. Data represent the mean ± SEM for 8–9 animals/group.

3.3 Trans-nonachlor significantly increases insulin-stimulated de novo lipogenesis

Increased hepatic de novo lipogenesis is the second major source of free fatty acid for esterification into triglyceride in NAFLD.4 Thus, the effects of trans-nonachlor exposure on basal and insulin-stimulated hepatic de novo lipogenesis were explored (Figure 3). Exposure to trans-nonachlor resulted in a concentration-related increase in 14C-acetate into the total lipid fraction with trans-nonachlor (20 μM; 3432.15 ± 243.64 cpm/mg) slightly, increasing acetate incorporation by 34% compared to vehicle (2567.65 ± 88.8 cpm/mg). However, this increase did not reach statistical significance. As anticipated, treatment with insulin for the final 8 hours of exposure significantly increased lipogenesis in vehicle-treated cells (4308.39 ± 479.2 vs. 2567.65 ± 88.8 cpm/mg; insulin vs. no insulin, respectively). Insulin-induction of lipogenesis was not significantly altered by exposure to trans-nonachlor with the exception of trans-nonachlor (2 μM) where insulin-stimulated 14C-acetate incorporation was not significantly greater than non-stimulated 14C-acetate incorporation. Trans-nonachlor (20 μM) did significantly increase insulin-stimulated acetate incorporation in concentration-dependent manner with significant increases of 41% compared to vehicle treated and 45% compared to trans-nonachlor (2 μM) treated cells receiving insulin for the final 8 hours of exposure. Therefore, these data indicate trans-nonachlor-induced neutral lipid accumulation may be due at least in part to increased fatty acid synthesis.

Figure 3.

Trans-nonachlor significantly increases insulin-stimulated de novo lipogenesis. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours with insulin-stimulation for the final 8 hours of exposure then lipogenesis assessed by 14C-acetate incorporation into total cellular lipids. Data represent the mean ± SEM for 5 animals/group. *P≤0.05 vs. matching trans-nonachlor concentration without insulin; #P≤0.05 vs. trans-nonachlor (0 μM) with insulin; &P≤0.05 vs. trans-nonachlor (2.0 μM) with insulin

3.4 Trans-nonachlor significantly increases FAS protein levels

The effects of trans-nonachlor exposure on the major lipogenic mediators SREBP1c and its target FAS were explored as potential mechanisms governing trans-nonachlor mediated alterations in lipogenesis (Figure 4). Exposure to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours resulted in a concentration related increase in FAS protein levels (Figure 4A) with trans-nonachlor (20 μM; 0.67 ± 0.17) significantly increasing FAS by 3.4-fold compared to vehicle treated cells (0 μM; 0.196 ± 0.04). Insulin stimulation significantly increased FAS protein levels in vehicle-treated cells (0 μM) by 2.6-fold. However, there was no significant insulin-stimulated increase in FAS levels in trans-nonachlor treated cells. Interestingly, trans-nonachlor exposure did not significantly alter levels of full-length SREBP1c (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Alteration of lipogenic mediators following trans-nonachlor exposure. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours with insulin-stimulation for the final 8 hours of exposure then lysates subjected to western blotting for (A) FAS or (B) full-length SREBP1c expression. Representative western blots are shown above the graphs. Data represent the mean ± SEM of n=6–7 animals/group. *P≤0.05 vs. matching trans-nonachlor concentration without insulin; #P≤0.05 vs. trans-nonachlor (0 μM) without insulin

3.5 Fatty acid oxidation/degradation is decreased by trans-nonachlor

While fatty acid uptake and de novo lipogenesis are the major sources of free fatty acids for esterification, fatty acid oxidation is a major mechanism through which intracellular free fatty acid levels are regulated. To examine if alterations in free fatty acid degradation may promote trans-nonachlor mediated intracellular neutral lipid accumulation, primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor (0, 0.2, or 20 μM) with or without OA (400 μM) to stimulate fatty acid oxidation as indicated by cellular β-HB levels (Figure 5). It should be noted that the mid-range concentration of trans-nonachlor (2.0 μM) was not explored for β-HB or VLDL secretion due to the fact that this concentration did not alter previous endpoints. As anticipated, OA treatment (0.575 ± 0.028 μmole/mg) significantly increased intracellular β-HB levels by 60% in vehicle exposed cells treated with BSA (0.359 ± 0.029 μmole/mg). Exposure to the lower concentration of trans-nonachlor (0.2 μM) did not significantly alter basal or OA-induced β-HB levels. However, trans-nonachlor (20 μM) significantly decreased both basal (0.208 ± 0.034 μmole/mg) and OA-induced (0.294 ± 0.044 μmole/mg) cellular β-HB levels by 42% and 49% compared to vehicle exposed BSA treated and OA treated cells, respectively. Taken together, these data indicate exposure to trans-nonachlor decreases both basal and OA-stimulated fatty acid oxidation which may promote intracellular fatty acid accumulation.

Figure 5.

Exposure to trans-nonachlor significantly inhibits fatty acid oxidation. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours with OA-stimulation for the final 8 hours of exposure then cellular levels of β-HB were measured as an index of fatty acid oxidation. Data represent the mean ± SEM of n=4–6 animals/group. *P≤0.05 vs. matching trans-nonachlor concentration without OA; #P≤0.05 vs. vehicle without OA; &P≤0.05 vs. vehicle and trans-nonachlor (0.2 μM) with OA

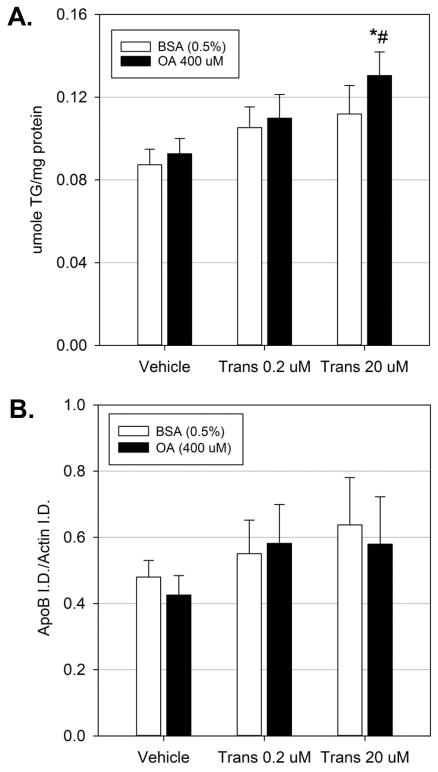

3.6 Triglyceride secretion is increased by the combination of trans-nonachlor and OA exposure

Secretion of triglyceride laden VLDL is a major mechanism through which intracellular neutral lipid/triglyceride levels are regulated in the hepatocyte. To determine if alterations in triglyceride secretion may promote trans-nonachlor mediated intracellular neutral lipid accumulation, both basal (BSA) and fatty acid-stimulated (OA) triglyceride secretion was determined (Figure 6A). Exposure to trans-nonachlor (0.2 or 20 μM) did not significantly increase basal triglyceride secretion. However, trans-nonachlor (20 μM) did significantly increase OA-stimulated triglyceride secretion into the media (0.130 ± 0.01 μmole/mg) compared to vehicle exposed BSA-treated (0.087 ± 0.007 μmole/mg) and OA-treated (0.093 ± 0.007 μmole/mg) cells by 49% and 40%, respectively. The current data indicate OA-stimulated triglyceride secretion in the form of triglyceride laden VLDL is not significantly impaired by trans-nonachlor. However, this secretion may not be sufficient to decrease intracellular triglyceride accumulation. Additionally, cellular levels of APOB100 were examined as an indicator of VLDL synthesis prior to secretion (Figure 6B). While trans-nonachlor exposure increased cellular APOB100 levels, this increase was not statistically significant.

Figure 6.

Exposure to trans-nonachlor increases OA-stimulated triglyceride secretion. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours with OA-stimulation for the final 8 hours of exposure then (A) media levels of triglyceride or (B) cellular levels of APOB were determined. Data represent the mean ± SEM of n=8–9 animals/group for media triglyceride and n=6 animals/group for cellular APOB. *P≤0.05 vs. vehicle without OA; #P≤0.05 vs. vehicle with OA

3.7 Exposure to trans-nonachlor does not significantly increase cellular oxidative stress

Alterations in cellular oxidative stress were explored to determine if exposure to trans-nonachlor significantly increased cellular oxidative stress as a potential mechanism to increase hepatocyte lipid accumulation. Lipid peroxidation, as determined by cellular MDA levels, was measured by TBARS assay (Supplementary figure 1A). Exposure to trans-nonachlor (0.2 and 20 μM) for 24 hours did not significantly alter cellular MDA levels indicating trans-nonachlor did not promote formation of reactive oxygen species. As a complimentary approach, cellular glutathione levels were determined as an index of cellular anti-oxidant capacity (Supplementary figure 1B). Exposure to trans-nonachlor (0.2 and 20 μM) did not significantly alter cellular glutathione levels. Thus, taken together, these data indicate exposure to trans-nonachlor did not increase cellular oxidative stress as a mechanism to alter lipid metabolism and promote lipid accumulation.

4. Discussion

One of the first in vivo reports of alterations in hepatic lipid metabolism following exposure to POPs was from experiments utilizing contaminated or refined salmon oil in conjunction with high fat diet feeding. These studies in both rats and mice demonstrated that intake of contaminated salmon oil in addition to high fat diet exacerbated high fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis.9,10 However, these studies did not address the relative steatotic potential of the individual compounds within these POPs mixtures. Our current data indicate direct exposure to trans-nonachlor has a greater steatotic effect than exposure to DDE or oxychlordane with significant increases in intracellular neutral lipid accumulation following 24 and 48 hours of trans-nonachlor exposure compared to non-significant increases following exposure to oxychlordane and DDE. Ward et al. (2016) recently demonstrated exposure to DDE (10 μM) significantly decreased OA-induced intracellular neutral lipid accumulation in McA hepatoma cells.15 Additionally, Liu et al. (2017) demonstrated exposure to DDE increases neutral lipid accumulation with significant increases in fatty acid composition in human HepG2 hepatoma cells.16 Thus, there are discrepancies in the currently observed effects of DDE on intracellular lipid accumulation in the current study and those previously reported in the literature which may be due to a difference in the cell type which was utilized in each study.

Given trans-nonachlor appeared to be the more pro-steatotic compound compared to oxychlordane and DDE, our subsequent studies utilized trans-nonachlor to explore the potential alterations in key physiological pathways governing hepatic lipid metabolism. Our current data indicate trans-nonachlor does not significantly increase Bodipy-labeled dodecanoic acid in primary hepatocytes. Thus, increased free fatty acid uptake does not appear to significantly mediate trans-nonachlor induced neutral lipid accumulation. Trans-nonachlor exposure resulted in an upward trend in basal cellular de novo lipogenesis. Upon stimulation with insulin, a positive regulator of hepatic de novo lipogenesis, concomitant exposure with trans-nonachlor significantly increased insulin-induced hepatocyte de novo lipogenesis in a concentration-dependent manner. However, it does not appear that this trans-nonachlor mediated increase in insulin-induced lipogenesis is due to increased insulin signaling as indicated by a failure of trans-nonachlor to increase insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt (Supplementary figure 2) or insulin-induced protein levels of FAS (Figure 4A). Conversely, it does not appear that exposure to trans-nonachlor significantly inhibits insulin signaling via the Akt pathway given there was no effect of trans-nonachlor exposure for 24 hours on insulin-induced phosphorylation of serine 473 on Akt. However, effects on other insulin signaling pathways cannot be determined from the present data.

Interestingly, our current data indicate a significant induction of FAS protein levels following 24 hours of exposure to trans-nonachlor (20 μM) to levels comparable to insulin-induction of FAS. These increased levels of FAS in non-insulin treated cells were associated with slight increases in hepatocyte lipogenesis as indicated by 14C-acetate incorporation into cellular lipids. The combination of trans-nonachlor (20 μM) and insulin-stimulation did not significantly increase cellular levels of FAS but did increase cellular lipogenesis. Thus, there is a disconnection between cellular levels of FAS and lipogenesis. Additionally, FAS is a well-known target gene of SREBP-1c.22 However, trans-nonachlor exposure for 24 hours did not significantly increase the protein levels of full-length SREBP-1c, which is regulated by mature SREBP-1c by positive feedback, indicating that the trans-nonachlor mediated increase in FAS protein levels may be independent of SREBP-1c activation.23,24

Recently, Moreau et al. (2009) discovered that activation of the pregnane × receptor (PXR) can induce FAS expression and lipogenesis in human hepatocytes without an accompanying increase in SREBP-1c expression.25 This is significant given trans-nonachlor is a reported PXR agonist.26–28 It should be noted that there was not a significant increase in full-length SREBP1c following insulin stimulation for 8 hours in the present study. This was unexpected given previous studies indicating significant upregulation of SREBP1c expression following insulin-stimulation in rat primary hepatocytes.18,29 While SREBP1c is the predominant SREBP1 isoform expressed in primary hepatocytes, the possibility arises that the currently utilized antibody is recognizing SREBP1a in addition to SREBP1c which would lead to a lack of insulin-induction given SREBP1a is not regulated by insulin.30,31 The possibility also arises that the increases in SREBP1c protein levels may have proceeded the increases in FAS levels. Given that insulin treatment increased lipogenesis, FAS protein levels, and Akt phosphorylation, it does not appear that the currently observed lack of SREBP1c induction is due to impaired insulin signaling. Future in-depth studies examining trans-nonachlor effects on basal and insulin-stimulated SREBP1c and FAS activities as well as their contributions to trans-nonachlor-mediated increased lipogenesis and neutral lipid accumulation are warranted to dissect the molecular mechanisms governing our currently observed effects on this key pathway of hepatic lipid metabolism.

Our present data indicate decreased fatty acid oxidation/degradation via mitochondrial β-oxidation may contribute to increased fatty acid availability for esterification into triglyceride. Exposure to trans-nonachlor (20 μM) decreased both basal and OA-stimulated fatty acid oxidation as indicated by intracellular β-HB levels. Recently, Liu et al (2017) discovered exposure to the OC compounds DDE and β-HCH significantly decreased the expression of proteins regulating fatty acid oxidation in human HepG2 cells while upregulating lipogenic genes.16 Thus, it appears that these two compounds and trans-nonachlor may share a common end effect on lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation. However, it is unclear if the currently observed effects of trans-nonachlor on fatty acid oxidation are a product of decreased expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-α (PPARα) genes as observed by Liu et al. (2017) or via inhibition of fatty acid oxidation at the level of disrupting carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1α (CPT-1α) activity via malonyl-CoA.32,33 Given our current data, generation of malonyl-CoA via increased de novo lipogenesis is a plausible mechanism through which trans-nonachlor decreases fatty acid oxidation. However, future studies will be necessary to determine if this decrease in fatty acid oxidation are a product of disrupted PPARα activity or decreased CPT-1α activity via the lipogenic intermediate malonyl-CoA.

Our current study utilized a concentration range from high nanomolar to low micromolar to assess the steatotic effects of the three targeted OC compounds, trans-nonachlor, oxychlordane, and DDE. After determining trans-nonachlor was the more pro-steatotic OC compound compared to oxychlordane and DDE, we utilized a concentration range of trans-nonachlor from high nanomolar to low micromolar (0.2, 2, and 20 μM) in subsequent studies to span concentrations which may be encountered in serum from high human exposures to potential target organ concentrations. In the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, high human exposure serum concentrations were as high as 129 to 160 ng/g (290 to 360 nM) in the non-Hispanic black population of the United States from 2000 to 2004.34 However, there are drastic variations in serum and tissue concentrations based on geographic location and frequency of use of OC compounds. For example, serum concentrations of DDT, the parent compound of DDE, have been reported to be as has as 743 ng/ml or 2.1 μM in Northeast India.35

Given the highly lipophilic nature of the OC compounds, especially those presently utilized, tissue bioaccumulation over time in lipid rich tissues would be expected to exceed serum levels. Depending on the study population, the adipose to serum ratios based on lipid adjusted values for DDE have been shown to range from 1.9 to 3.9 indicating significant adipose accumulation.36,37 While most biomonitoring studies have utilized serum and to a lesser extend adipose tissue OC levels, there is a relative lack of studies examining hepatic levels of many OC compounds, especially trans-nonachlor. Dewailly et al. (1999) evaluated postmortem tissue levels in brain, liver, and adipose of native Greenlanders. Interestingly, mean liver levels of trans-nonachlor were 1,502 μg/kg of lipid or approximately 3.4 μM with a highest range value of 3,880 μg/kg or approximately 8.7 μM.38 While the Greenland population is heavily exposed to OC contaminants, these reported liver trans-nonachlor concentrations demonstrate that human exposure can reach the level of the high concentrations of trans-nonachlor (2 and 20 μM) used in the present study.

In summary, our present data demonstrate direct exposure to the bioaccumulative OC compound trans-nonachlor produces an increase in intracellular neutral lipid accumulation that is associated with increased intracellular triglyceride levels, the hallmark of hepatic steatosis. This steatotic effect of trans-nonachlor is accompanied by increased de novo lipogenesis and the lipogenic mediator FAS and decreased fatty acid oxidation. Thus, increased lipogenesis and decreased fatty acid degradation without an appropriate compensatory increase in triglyceride secretion appear to mediate the steatotic effect of trans-nonachlor exposure in rat primary hepatocytes. However, future studies are warranted to elucidate the molecular mechanisms governing the currently observed effects on lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation as well as to determine if trans-nonachlor exposure at environmentally relevant dosages will promote NAFLD in an in vivo model of type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Exposure to trans-nonachlor does not alter cellular lipid peroxidation or glutathione levels. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours then cellular levels of (A) MDA or (B) glutathione were measured to assess lipid peroxidation and anti-oxidant capacity, respectively. Data represent the mean ± SEM of n=6 animals/group.

Trans-nonachlor does not alter insulin-induced phosphorylation of AKT. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours with insulin stimulation for the last 15 minutes of exposure then cellular levels of phospho-AKT (pAKT; Ser473) and total AKT (tAKT) were measured by western blot and expressed as pAKT/tAKT. Representative western blots are shown above the graphs. Data represent the mean ± SEM of n=5–7 animals/group. *P≤0.05 vs. matching trans-nonachlor concentration without insulin

Acknowledgments

The present work was funded by grant #1R15ES026791-01 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Literature cited

- 1.Wilson PW, Kannel WB, Silbershatz H, D’Agostino RB. Clustering of metabolic factors and coronary heart disease. Archives of internal medicine. 1999;159(10):1104–1109. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.10.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Morselli-Labate AM, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. The American journal of medicine. 1999;107(5):450–455. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a feature of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2001;50(8):1844–1850. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD, Parks EJ. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115(5):1343–1351. doi: 10.1172/JCI23621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee RG. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a study of 49 patients. Human pathology. 1989;20(6):594–598. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bacon BR, Farahvash MJ, Janney CG, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: an expanded clinical entity. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(4):1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee DH, Steffes MW, Sjodin A, Jones RS, Needham LL, Jacobs DR., Jr Low dose organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls predict obesity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance among people free of diabetes. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e15977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor KW, Novak RF, Anderson HA, et al. Evaluation of the association between persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and diabetes in epidemiological studies: a national toxicology program workshop review. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(7):774–783. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruzzin J, Petersen R, Meugnier E, et al. Persistent organic pollutant exposure leads to insulin resistance syndrome. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(4):465–471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim MM, Fjaere E, Lock EJ, et al. Chronic consumption of farmed salmon containing persistent organic pollutants causes insulin resistance and obesity in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker NA, Karounos M, English V, et al. Coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls impair glucose homeostasis in lean C57BL/6 mice and mitigate beneficial effects of weight loss on glucose homeostasis in obese mice. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(1):105–110. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker NA, English V, Sunkara M, Morris AJ, Pearson KJ, Cassis LA. Resveratrol protects against polychlorinated biphenyl-mediated impairment of glucose homeostasis in adipocytes. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry. 2013;24(12):2168–2174. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahlang B, Falkner KC, Gregory B, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyl 153 is a diet-dependent obesogen that worsens nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in male C57BL6/J mice. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry. 2013;24(9):1587–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulligan C, Kondakala S, Yang EJ, et al. Exposure to an environmentally relevant mixture of organochlorine compounds and polychlorinated biphenyls Promotes hepatic steatosis in male Ob/Ob mice. Environ Toxicol. 2017;32(4):1399–1411. doi: 10.1002/tox.22334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ward AB, Dail MB, Chambers JE. In Vitro effect of DDE exposure on the regulation of lipid metabolism and secretion in McA-RH7777 hepatocytes: A potential role in dyslipidemia which may increase the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2016;37:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Q, Wang Q, Xu C, et al. Organochloride pesticides impaired mitochondrial function in hepatocytes and aggravated disorders of fatty acid metabolism. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46339. doi: 10.1038/srep46339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kondakala S, Lee JH, Ross MK, Howell GE., 3rd Effects of acute exposure to chlorpyrifos on cholinergic and non-cholinergic targets in normal and high-fat fed male C57BL/6J mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2017;337:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell G, 3rd, Deng X, Yellaturu C, et al. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress insulin-induced SREBP-1c transcription via reduced trans-activating capacity of LXRalpha. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791(12):1190–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell GE, III, Mulligan C, Young D, Kondakala S. Exposure to chlorpyrifos increases neutral lipid accumulation with accompanying increased de novo lipogenesis and decreased triglyceride secretion in McArdle-RH7777 hepatoma cells. Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2016;32:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howell G, 3rd, Mangum L. Exposure to bioaccumulative organochlorine compounds alters adipogenesis, fatty acid uptake, and adipokine production in NIH3T3-L1 cells. Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2011;25(1):394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1957;226(1):497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latasa MJ, Griffin MJ, Moon YS, Kang C, Sul HS. Occupancy and function of the -150 sterol regulatory element and -65 E-box in nutritional regulation of the fatty acid synthase gene in living animals. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(16):5896–5907. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5896-5907.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cagen LM, Deng X, Wilcox HG, Park EA, Raghow R, Elam MB. Insulin activates the rat sterol-regulatory-element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) promoter through the combinatorial actions of SREBP, LXR, Sp-1 and NF-Y cis-acting elements. The Biochemical journal. 2005;385(Pt 1):207–216. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng X, Zhang W, IOS, et al. FoxO1 inhibits sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) gene expression via transcription factors Sp1 and SREBP-1c. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287(24):20132–20143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.347211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moreau A, Teruel C, Beylot M, et al. A novel pregnane X receptor and S14-mediated lipogenic pathway in human hepatocyte. Hepatology. 2009;49(6):2068–2079. doi: 10.1002/hep.22907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuetz EG, Brimer C, Schuetz JD. Environmental xenobiotics and the antihormones cyproterone acetate and spironolactone use the nuclear hormone pregnenolone X receptor to activate the CYP3A23 hormone response element. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54(6):1113–1117. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.6.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemaire G, de Sousa G, Rahmani R. A PXR reporter gene assay in a stable cell culture system: CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 induction by pesticides. Biochemical pharmacology. 2004;68(12):2347–2358. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs MN, Nolan GT, Hood SR. Lignans, bacteriocides and organochlorine compounds activate the human pregnane X receptor (PXR) Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;209(2):123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azzout-Marniche D, Becard D, Guichard C, Foretz M, Ferre P, Foufelle F. Insulin effects on sterol regulatory-element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) transcriptional activity in rat hepatocytes. The Biochemical journal. 2000;350(Pt 2):389–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimomura I, Shimano H, Horton JD, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Differential expression of exons 1a and 1c in mRNAs for sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 in human and mouse organs and cultured cells. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;99(5):838–845. doi: 10.1172/JCI119247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eberle D, Hegarty B, Bossard P, Ferre P, Foufelle F. SREBP transcription factors: master regulators of lipid homeostasis. Biochimie. 2004;86(11):839–848. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGarry JD, Leatherman GF, Foster DW. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase I. The site of inhibition of hepatic fatty acid oxidation by malonyl-CoA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1978;253(12):4128–4136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGarry JD, Mannaerts GP, Foster DW. A possible role for malonyl-CoA in the regulation of hepatic fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1977;60(1):265–270. doi: 10.1172/JCI108764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.CDC; Department of Health and Human Services CfDCaP, editor. Fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra K, Sharma RC, Kumar S. Organochlorine pollutants in human blood and their relation with age, gender and habitat from North-east India. Chemosphere. 2011;85(3):454–464. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Artacho-Cordon F, Fernandez-Rodriguez M, Garde C, et al. Serum and adipose tissue as matrices for assessment of exposure to persistent organic pollutants in breast cancer patients. Environ Res. 2015;142:633–643. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arrebola JP, Cuellar M, Claure E, et al. Concentrations of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in human serum and adipose tissue from Bolivia. Environ Res. 2012;112:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dewailly E, Mulvad G, Pedersen HS, et al. Concentration of organochlorines in human brain, liver, and adipose tissue autopsy samples from Greenland. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107(10):823–828. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Exposure to trans-nonachlor does not alter cellular lipid peroxidation or glutathione levels. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours then cellular levels of (A) MDA or (B) glutathione were measured to assess lipid peroxidation and anti-oxidant capacity, respectively. Data represent the mean ± SEM of n=6 animals/group.

Trans-nonachlor does not alter insulin-induced phosphorylation of AKT. Rat primary hepatocytes were exposed to trans-nonachlor for 24 hours with insulin stimulation for the last 15 minutes of exposure then cellular levels of phospho-AKT (pAKT; Ser473) and total AKT (tAKT) were measured by western blot and expressed as pAKT/tAKT. Representative western blots are shown above the graphs. Data represent the mean ± SEM of n=5–7 animals/group. *P≤0.05 vs. matching trans-nonachlor concentration without insulin