Summary

Objective

Food environments can influence food selection and hold the potential to reduce obesity, non‐communicable diseases and their inequalities. ‘Consumer nutrition environments’ describe what consumers encounter within a food retail outlet, including products, price, promotion and placement. This study aimed to summarize the attributes that have been examined in existing peer‐reviewed studies of Australian consumer nutrition environments, identify knowledge gaps and provide recommendations for future research.

Methods

A systematic search of peer‐reviewed literature was conducted. Sixty‐six studies that assessed an aspect of within‐store consumer nutrition environments were included.

Results

Most studies were published from 2011 onwards and were conducted in capital cities and in supermarkets. Studies assessed the domains of product (40/66), price (26/66), promotion (16/66) and placement (6/66). The most common research themes identified were assessment of the impact of area socioeconomic status (13/66), remoteness (9/66) and food outlet type (7/66) on healthy food prices; change in price of healthy foods (6/66); variety of healthy foods (5/66); and prevalence of unhealthy child‐orientated products (5/66).

Conclusions

This scoping review identified a large number of knowledge gaps. Recommended priorities for researchers are as follows: (1) develop consistent observational methodology, (2) consider consumer nutrition environments in rural and remote communities, (3) develop an understanding of food service outlets, (4) build on existing evidence in all four domains of product, price, placement and promotion and (5) determine effective policy and store‐based interventions to increase healthy food selection.

Keywords: Fast food, food environments, food retail, supermarkets

Introduction

Globally, poor diet is one of the most important risk factors for early deaths 1, and few Australians adhere to the national dietary guidelines 2, 3. The 2011–2012 Australian Health Survey found only a third of the population met fruit consumption recommendations, less than 4% consumed the minimum recommended serves of vegetables and 35% of total energy intake came from discretionary foods, which are not essential for a healthy diet 4. Increasing population adherence to dietary guidelines to prevent and control obesity, non‐communicable diseases and their inequalities is a public health priority 5, 6.

Making improvements in population diets requires multifaceted and multilevel interventions addressing macro‐level and built environments, as well as social and individual factors 7. Approaches to promoting healthy diets have been proposed in the ‘Nourishing’ and INFORMAS frameworks, which both highlight the important role of the food environment 8, 9. The term ‘food environment’ is used to describe the surroundings, opportunities and conditions that influence people's food choices and nutritional status and includes the physical, economic, policy and sociocultural environments 9. Because food environments can create conditions that are supportive or unsupportive of healthy eating 9, actions to improve these environments have the potential to promote consumption of more healthful foods and beverages at the population level 7, 9, 10.

One aspect of food environment research investigates what consumers encounter within a food outlet, referred to by Glanz et al. as the ‘consumer nutrition environment’ 11. Domains of the consumer nutrition environment that potentially influence food purchasing and eating patterns have been identified by Glanz et al. and include the following: products, i.e. the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods, product assortment, design of products and packaging and provision of supermarket own brands; price, i.e. the price of healthy and unhealthy foods, price sensitivity and elasticity and price promotions; placement, i.e. the in‐store location of products or shelf location of products; and promotions, i.e. health messages, promotions targeting children and other methods including signage, banners, samples and taste testing 12.

There is some evidence of an association between consumer nutrition environments and dietary outcomes 13. For example, supermarket interventions to improve the healthfulness of retail food environments have shown promising results in influencing dietary behaviour 10, 14. Strategies have included using pricing, monetary incentives, product availability and placement and promotional messages to increase the availability, appeal and purchase of healthy foods 15, 16. Furthermore, managing food position or order in food service settings (e.g. placing healthy options in easily accessible or more prominent positions) has been found to influence food choice 17. Thus, consumer nutrition environments hold great promise as settings for health promotion interventions and policies targeting healthy eating.

A number of recent systematic reviews have been conducted to synthesize the consumer nutrition environment literature in this emerging field (14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). However, none of these reviews have addressed all four domains that can influence food purchasing and eating patterns (i.e. product, price, placement and promotion). Furthermore, they have focused on a specific outcome such as diet or childhood overweight and obesity 18, 19, 20, 24, the measurement of consumer nutrition environments 21, 22, 23 or interventions 14, 15, 16. Most of the studies included in these reviews have been conducted in the USA. However, consumer nutrition environments are likely to be context specific, and as such, empirical findings from the USA may not always be internationally transferable 25. For example, between‐country differences have been observed in relation to the placement of snack foods in supermarkets 26, the size and nutrient profile of packaged supermarket foods 27, 28 and the promotion of healthy and discretionary foods in supermarket advertising 29. In recognition of unique food environment issues faced in Canada, researchers have synthesized country‐specific literature and identified gaps in knowledge to set priorities for future research and practice 30.

To date, there has not been a review of consumer nutrition environment research in Australia. In order to develop an evidence base that could be used to inform appropriate and effective public policy, a synthesis of consumer nutrition environment studies specific to the Australian context is needed. Scoping reviews have been defined as the process of mapping existing literature and identifying key concepts, theories and sources of evidence. A scoping review can be used to summarize and disseminate research findings and identify research gaps in the literature 31. The aims of this scoping review were to (1) summarize existing peer‐reviewed Australian studies that have examined consumer nutrition environments, (2) identify knowledge gaps and (3) provide recommendations for future research. More specifically, the following research question is addressed: which domains of the consumer nutrition environment (i.e. product, price, placement and promotion) have been examined in Australian peer‐reviewed research?

Methods

Conceptual framework

The conceptual model of community nutrition environments provides a framework for this review 11. The model identifies four types of nutrition environments: (i) community nutrition environments, which describe the distribution of neighbourhood food sources including the number, type, location and accessibility of food outlets, such as stores and restaurants, present in a community; (ii) organizational nutrition environments, which describe the provision of foods to defined groups rather than the general population, e.g. in the workplace, school, sporting clubs or at home; (iii) information environments, which capture the influence of media reporting and advertising; and (iv) consumer nutrition environments, which describe the within‐store environment of food outlets, including stores and restaurants, and are the focus of this review. Measures of consumer nutrition environments can include nutritional quality, product quality or freshness, price, promotions, placement and provision of nutritional information. The literature was reviewed for the consumer nutrition environment domains of product, price, placement and promotion 12.

Scoping review protocol

This scoping review followed the five‐step protocol described by Arksey and O'Malley and others 31, 32, 33: (i) define the research question, (ii) identify relevant studies, (iii) select studies to include, (iv) chart, or synthesize, the data and (v) summarize and report the results.

For the first step, the research question was defined as: which domains of the consumer nutrition environment (i.e. product, price, placement and promotion) have been examined in Australian peer‐reviewed research?

Search strategy

For the second step, a search strategy was developed to identify relevant studies. Key concepts of the research question were identified as ‘consumer nutrition environments’, ‘food retail outlet’ and ‘food and health’ and limited to Australia. Search terms were developed for each concept (Table 1). The literature search was conducted in February 2018 using the Ovid MEDLINE and CINAHL databases using the search terms listed in Table 1, limiting results to human studies in English. This was supplemented by a snowball search of the reference lists and citations of the selected articles and hand searching. This search strategy identified 765 unique studies. A further 28 studies were identified by snowball and hand searching the selected documents.

Table 1.

Search terms used

| Concept | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Food and health | diet* or intake* or nutrition or consumption or Food or fast food* or processed food* or snack* or fruit* or vegetable* or health* or unhealthy or obesity or overweight or BMI or body mass index or weight or heart or diabete* |

| Food retail outlet | food store* or food outlet* or retail* or retail outlet* or food supply or supermarket* or grocery store* or convenience store* or restaurant* or cafe* or takeaway* or corner store* or market or farmers market* or garden* or community garden or vegetable garden or cafeteria or vending machine or canteen* or greengrocer or bakery or butcher or shop* or food hall |

| Consumer nutrition environments | availab* or price or promotion* or marketing or placement or nutrition information or marketing or consumer nutrition environment* or pric* or cost or information or market basket or shelf space or display* or prominence or polic* or advertis* or audit or NEMS |

| Australia | Australia or Perth or Victoria or New South Wales or Queensland or Northern Territory or Western Australia or South Australia or Adelaide or Melbourne or Sydney or Brisbane or Canberra or Tasmania or Hobart or Alice Springs or Australian Capital Territory |

Study selection

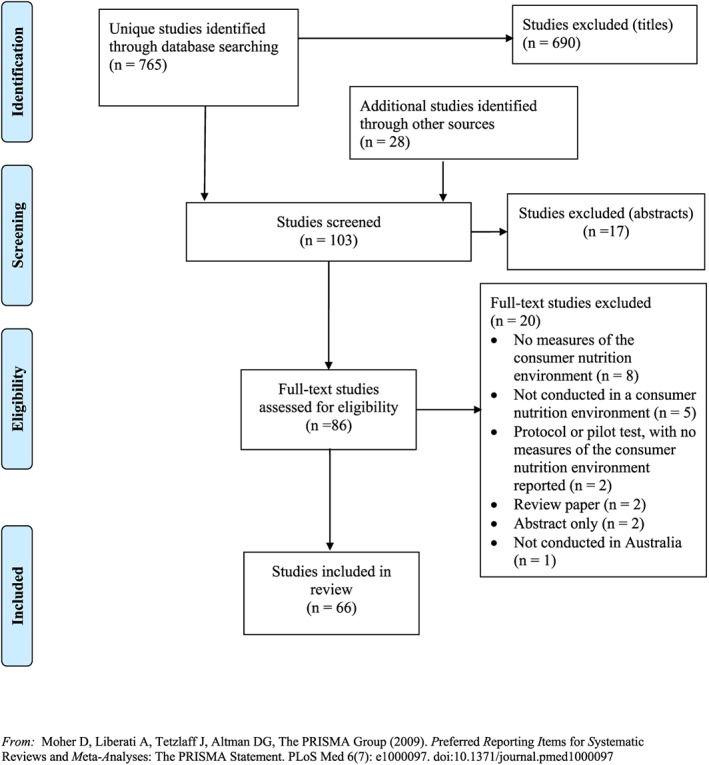

The third step of the Arksey and O'Malley protocol involved selecting which studies to include 31. The titles and abstracts identified in the review (n = 793) were assessed against inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2) to select studies for further screening. After screening titles and abstracts, the full text of 86 studies was assessed for eligibility (Figure 1). Full text of all studies was reviewed by the first author. The second and third authors reviewed approximately 10% of studies against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and any disagreements about study selection were discussed and resolved by all authors. This feedback process was adopted at the beginning of the review to ensure a consistent approach to assessment of all studies.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Language | English | All other languages |

| Year | 1970+ | <1969 |

| Country | Australia | International studies without relevance to Australia |

| Population | Humans | Animal |

| Food products | All food and non‐alcoholic beverages | Alcohol and tobacco |

| Food environments | Consumer nutrition environments, i.e. food retail outlets including supermarkets, convenience stores, restaurants and fast food outlets | Community nutrition environments, organizational nutrition environments and information environments, without reference to consumer nutrition environments |

| Setting | Consumer nutrition environments, including products or packaging collected in specified consumer nutrition environments | Online food retail and food service websites; controlled environments including simulated food environments; simulated food packaging; or assessments of the general food supply |

| Study design | Observational (audits, surveys, product database analysis and point‐of‐sale data), randomized controlled trials, qualitative (interviews and focus groups) and social marketing campaign evaluation | Protocols, reviews and survey instrument development that provided no results |

| Outcomes of interest | Consumer nutrition environment attributes, i.e. available healthy and unhealthy foods; price; promotion; and placement | Food purchases, consumer purchase behaviour/decisions, consumer understanding of nutritional information, drivers of the environment and impact of policy changes |

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analyses flow diagram.

This scoping review included literature that described consumer nutrition environments accessible to the general population, i.e. food retail outlets such as supermarkets, convenience stores, restaurants and fast food outlets (Table 2). Studies that assessed information from products or packaging collected from specified consumer nutrition environments were included (e.g. studies that described the price or nutritional quality of packaged foods in specific food outlets, where the data collection process was described in detail including specifying the locations and outlets under investigation). Studies that assessed an aspect of consumer nutrition environments using online food retail or food service websites were excluded. Studies that assessed the broader food supply were excluded (e.g. studies that described the price or nutritional quality of packaged foods in the food supply, using data collected from a wide range of outlets that were not specified). Studies that described aspects of the community nutrition environment (i.e. the number, type, location and accessibility of food outlets), organizational nutrition environment (e.g. workplace, school, hospitals, sporting clubs or home) or information environment (i.e. media reporting and advertising) without reference to consumer nutrition environments were also excluded.

Data synthesis

For the fourth step, the data were charted to enable synthesis and identify themes. Information that described the following was collected: first author, year of publication, Australian state or territory, location (i.e. rural, remote, metropolitan and capital city), study design, assessment tools, type of retail food outlet (Table 3) and findings. Data relating to any of the four domains of consumer nutrition environments were recorded for each study and further classified into the following subdomains identified by Glanz et al. 12: (a) product availability and quality, (b) product assortment, (c) design of products and packaging, (d) nutritional quality, (e) provision of supermarket own brand products, (f) pricing strategy, (g) price sensitivity and elasticity, (h) price promotions, (i) in‐store location, (j) shelf location, (k) health messages, (l) promotions targeting children and (m) other promotions.

Table 3.

Types of food retail outlets that have been examined in Australian studies

| Food retail outlet | Description |

|---|---|

| Supermarket | Stores are part of a supermarket chain, owned and operated by a large corporation |

| Independent supermarket/grocery store | Supermarkets operated independently or under franchise |

| Discount supermarket/grocery store | Supermarkets that sell cheaper, discount groceries with a focus on price rather than service or convenience, often part of a chain |

| Specialist food outlet | Cater to specific consumer needs, e.g. ethnic food store, health food, delicatessen, butcher, fishmonger, bakery, cake shop and greengrocer (fruit and vegetable stores) |

| Fast food | Also referred to as Quick Service Restaurants, typically part of a chain or franchise, includes takeaway, drive‐through and seated options |

| Takeaway | Ready‐to‐eat food sold for consumption off the premises |

| Community store | A shop located in a remote Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community, owned by the community who employ a store manager to run the store on behalf of the community 110 |

| Convenience store | Neighbourhood stores that sell groceries, ready‐to‐eat snacks and other non‐food items |

Results

Characteristics of reviewed studies

In accordance with the final stage of the scoping review protocol adopted, a summary of the extent, nature and distribution of the studies is given. Sixty‐six studies were selected for inclusion in this scoping review, and a summary is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of Australian consumer nutrition environment studies

| First author | Year | State or territory | Location | Type of retail food outlet | Assessment tool | Study outcomes | Consumer nutrition environment domain | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Price | Placement | Promotion | |||||||

| Ball 53 | 2009 | VIC | Capital city | Multiple | Structured checklist | Socioeconomic inequalities | b | f | – | – |

| Ball 48 | 2015 | VIC | Capital city | Supermarket | Transaction data | Food purchases and eating behaviour | – | g | – | – |

| Ball109 | 2016 | VIC | Capital city | Supermarket | Transaction data | Food purchases and eating behaviour | – | – | – | k |

| Brimblecombe 61 | 2009 | NT | Remote | Multiple | Transaction data and food orders | Community dietary quality | d | f | – | – |

| Brimblecombe 60 | 2013 | NT | Remote | Community store | Transaction data | Community dietary quality | d | – | – | – |

| Brimblecombe83 | 2017 | NT | Remote | Community store | Transaction data | Food purchases | – | g | – | k, m |

| Burns 43 | 2004 | VIC | Rural | Supermarket | Market basket survey | Food security | a | f | – | – |

| Cameron 88 | 2013 | VIC | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Snack food shelfspace | – | – | j | – |

| Cameron87 | 2017 | VIC | Multiple | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Placement of snack foods and fresh produce | – | – | i, j | – |

| Campbell 93 | 2014 | NSW | Metropolitan | Supermarket | Interviews and focus groups | Impact of child‐targeted in‐store marketing | – | – | – | l |

| Carter 90 | 2013 | WA | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Compliance with voluntary guidelines | – | – | – | k |

| Chapman 62 | 2006 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Nature and extent of child‐targeted packaging | d | – | – | l |

| Chapman 74 | 2013 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Comparison of supermarket own brands with brands | e | f | – | – |

| Chapman 55 | 2014 | NSW | Multiple | Multiple | Standardized recording sheet | Food security | b | f | – | – |

| Cleanthous 73 | 2011 | NSW | Metropolitan | Supermarket | Handheld terminals | Comparison of supermarket own brands with brands | e | – | – | – |

| Crawford 49 | 2017 | NSW | Capital city | Multiple | Market basket survey | Food security | a, b | f | – | – |

| Dixon 86 | 2006 | VIC | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet and digital photographs | Displays of snack food | – | – | i | l, m |

| Ferguson 75 | 2016 | NT | Remote | Multiple | Transaction data | Food affordability | – | f | – | – |

| Ferguson 84 | 2016 | Multiple | Remote | Community store | Transaction data and semi‐structured interviews | Food security | – | g | – | – |

| Giskes 40 | 2007 | QLD | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Impact of perceptions on food purchases | a | f | – | – |

| Harrison 34 | 2007 | QLD | Multiple | Not specified | Market basket survey | Food security | a | f | – | – |

| Harrison 35 | 2010 | QLD | Multiple | Not specified | Market basket survey | Food security | a | f | – | – |

| Haskelberg 57 | 2016 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Digital photographs | Serving sizes present on packaging | c, d | – | – | – |

| Hebden 63 | 2011 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Nature and extent of child‐targeted packaging | d | – | – | l |

| Hobin 66 | 2014 | Not specified | Not specified | Fast food | Standardized recording sheet | Nutritional quality of fast food children's menus | d | – | – | – |

| Hughes 69 | 2013 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Digital photographs | Nature and extent of health claims on packaging | d | – | – | k |

| Inglis 51 | 2008 | VIC | Capital city | Multiple | Questionnaire | Eating behaviour | a | f | – | – |

| Innes‐Hughes 44 | 2012 | NSW | Metropolitan | Multiple | Structured checklist | Food availability | a | – | – | – |

| Lawrence 37 | 1999 | Multiple | Multiple | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Implementation of a health claim on packaging | a | f | – | k |

| Le 82 | 2016 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Transaction data | Cost‐effectiveness of an intervention | – | g | – | – |

| Lee 94 | 1996 | NT | Remote | Community store | Food orders | Implementation of community nutrition policy | a | – | – | k, m |

| Lee 47 | 1996 | QLD | Remote | Community store | Food orders | Community dietary quality | d | – | – | – |

| Lee 36 | 2002 | QLD | Multiple | Not specified | Market basket survey | Food security | a | f | – | – |

| Lee 78 | 2016 | QLD | Capital city | Supermarket | Market basket survey | Effect of potential fiscal policy actions | – | f | – | – |

| Lewis 96 | 2002 | VIC | Multiple | Supermarket | Interviews and questionnaire | Effectiveness of a supermarket intervention | – | – | – | m |

| McManus 52 | 2007 | WA | Capital city | Multiple | Standardized recording sheet | Food security | a | f | – | – |

| Mehta 64 | 2012 | SA | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Nature and extent of child‐targeted packaging | d | – | – | k, l |

| Meloncelli 68 | 2016 | QLD | Rural | Supermarket | Purchase of included products | Nutritional quality of child‐targeted products | d | – | – | k, l |

| Millichamp 38 | 2013 | QLD | Capital city | Multiple | Market basket survey | Comparison of food outlet types | a, b | f | – | – |

| Ni Mhurchu 28 | 2015 | NSW | Metropolitan | Supermarket | Digital photographs | Nutrient profiling of packaged foods | d | – | – | k |

| Palermo 77 | 2008 | VIC | Rural | Supermarket | Market basket survey | Factors that influence food cost | – | f | – | – |

| Palermo 50 | 2016 | VIC | Multiple | Multiple | Market basket survey | Food security | – | f | – | – |

| Pollard 39 | 2014 | WA | Multiple | Multiple | Market basket survey | Geographic determinants of food security | a | f | – | – |

| Savio 65 | 2013 | SA | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Description of child‐targeted product reformulation | d | – | – | – |

| Scott 95 | 1991 | WA | Metropolitan | Supermarket | Questionnaires | Effectiveness of a supermarket intervention | – | – | – | m |

| Thornton 85 | 2012 | VIC | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Snack food display locations | – | – | i, j | – |

| Thornton 26 | 2013 | VIC | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet and checklist | Snack food display locations | – | – | i, j | – |

| Trevena 70 | 2014 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Digital photographs | Nutrient reduction | d | – | – | – |

| Trevena 71 | 2014 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Digital photographs | Nutrient reduction | d | – | – | – |

| Trevena 72 | 2015 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Digital photographs | Comparison of supermarket own brands with brands and nutrient reduction | d, e | – | – | – |

| Tsang 45 | 2007 | SA | Capital city | Multiple | Market basket survey | Food security | a | f | – | – |

| Tyrell 46 | 2003 | NT | Remote | Community store | Market basket survey | Impact of a community diabetes prevention project | a | – | – | – |

| Vinkeles Melchers 89 | 2009 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Shopper dockets and standardized recording sheet | Food purchases | – | – | j | – |

| Walker 54 | 2008 | VIC | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Proportion of snacks that were healthy | b, c, d | – | – | – |

| Walker 56 | 2010 | VIC | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Comparison of nutrient profiles over time | c, d | – | – | k |

| Ward 76 | 2012 | SA | Rural | Supermarket | Market basket survey | Food security | – | f | – | – |

| Wellard 58 | 2011 | Multiple | Metropolitan | Fast food | Standardized recording sheet | Provision of nutritional information for fast food | c | – | – | – |

| Wellard 81 | 2015 | NSW | Capital city | Fast food | Standardized recording sheet | Provision of nutritional information for fast food | – | f | – | – |

| Wellard 59 | 2015 | Multiple | Metropolitan | Fast food | Standardized recording sheet | Provision of nutritional information for fast food | c | – | – | – |

| Wellard 91 | 2015 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Digital photographs | Nutrient profiling of packaged foods | d | – | – | k |

| Wellard 92 | 2016 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Digital photographs | Nutrient profiling of packaged foods | d | – | – | – |

| Williams 80 | 2004 | NSW | Metropolitan | Multiple | Market basket survey | Food affordability | – | f | – | – |

| Williams 79 | 2009 | NSW | Metropolitan | Multiple | Market basket survey | Food affordability | – | f | – | – |

| Winkler 42 | 2006 | QLD | Capital city | Supermarket | Standardized recording sheet | Socioeconomic inequalities | a, b | f | – | – |

| Wong 41 | 2011 | SA | Capital city | Multiple | Market basket survey | Food security | a | f | – | – |

| Wu 67 | 2015 | NSW | Capital city | Supermarket | Digital photographs | Comparison of gluten free with standard foods | d | – | – | – |

Consumer nutrition environment findings: (a) product availability and quality, (b) product assortment, (c) design of products and packaging, (d) nutritional quality, (e) provision of supermarket own brand products, (f) pricing strategy, (g) price sensitivity and elasticity, (h) price promotions, (i) in‐store location, (j) shelf location, (k) health messages, (l) promotions targeting children and (m) other promotions.

NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; SA, South Australia; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

Few studies (4/66) were published before 2002, and most (41/66) were published since 2011. Over half of the studies were conducted in the more populous states of New South Wales (21/66) and Victoria (16/66). Nine studies were conducted in Queensland, seven in the Northern Territory and five each in South Australia and Western Australia. More than half of the studies were conducted in capital cities (35/66). Some were conducted in metropolitan areas such as regional towns and centres (9/55), remote regions (8/66) or rural areas (4/66). Nine studies were conducted across a range of geographic regions.

Almost all studies were observational in design (i.e. audits, surveys, product database analysis and point‐of‐sale data) (56/66), followed by qualitative studies (5/66) and randomized controlled trials (4/66). Supermarkets were the most studied type of food retail outlet (38/66) followed by community stores (6/66) and fast food outlets (4/66). Around one‐fifth (15/66) studied multiple types of food retail outlets. The measurement tools used by most studies were standardized recording sheets (19/66) followed by market basket surveys (16/66), digital photographs (9/66), point‐of‐sale data (6/66), structured checklists (2/66), questionnaires (2/66), store food orders or invoices (2/66), interviews or focus groups (2/66) and handheld devices (1/66). Six studies utilized more than one measurement tool.

Table S1 summarizes findings from the studies, for each domain and subdomain examined, grouped under common themes. The large number of themes, and the general lack of consistency or agreement in findings, informed the iterative scoping review process. Thus, this study's objective was to summarize which domains of the consumer nutrition environment have been examined and the approaches used, rather than what was found.

The domain most studied was product (40/66), followed by price (26/66), promotion (16/66) and placement (6/66). For each of these domains, the subdomains and themes examined are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Themes identified in Australian consumer nutrition environment studies

| Domain and subdomain | Themes relating to healthy foods (citations) | Number of studies | Themes relating to less healthy/unhealthy foods (citations) | Number of studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product (n = 40) | ||||

| (a) Product availability and quality (n = 17) | Impact of level of remoteness on availability of healthy foods 34, 35, 36, 37 | 4 | Availability of unhealthy foods 44, 52 | 2 |

| Impact of area socioeconomic status on availability of healthy foods 38, 40, 41, 42 | 4 | |||

| Impact of food outlet type on availability of healthy foods 38, 43, 44, 45 | 4 | |||

| Impact of availability of healthy foods on food choice 40 | 1 | |||

| Impact of perceived availability of healthy foods 40, 51 | 2 | |||

| Interventions or policies to increase availability of healthy foods 46, 47 | 2 | |||

| Quality of fresh produce 38, 39, 49 | 3 | |||

| (b) Product assortment (n = 6) | Variety of healthy foods available 38, 42, 49, 53, 55 | 5 | Variety of unhealthy foods available 54 | 1 |

| (c) Design of products or packaging (n = 5) | Changes in pack size of healthy foods 56 | 1 | Recommended serving sizes of unhealthy foods 54, 57 | 2 |

| Provision of nutrition information for unhealthy foods in fast food outlets 58, 59 | 2 | |||

| (d) Nutritional quality (n = 18) | Nutritional quality of healthy foods in remote communities 47 | 1 | Prevalence of foods with poor nutritional quality in remote communities 60, 61 | 2 |

| Prevalence of healthy child‐orientated products 62, 63 | 2 | Prevalence of unhealthy child‐orientated products 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 | 5 | |

| Classification of packaged foods as healthy 28, 54, 67 | 3 | Classification of packaged foods as unhealthy 28, 57, 67 | 3 | |

| Nutritional quality of products perceived as healthy 56, 69 | 3 | Nutrient reduction in processed foods 70, 71, 72 | 3 | |

| Nutritional quality of child‐orientated products 68 | 1 | |||

| (e) Provision of supermarket own brand products (n = 3) | Nutritional quality of healthy supermarket own brand foods 72, 73 | 2 | Nutritional quality of supermarket own brand processed foods 72 | 1 |

| Cost comparison of healthy supermarket own brand foods with the branded equivalent 74 | 1 | Cost comparison of unhealthy supermarket own brand foods with the branded equivalent 74 | 1 | |

| Price (n = 26) | ||||

| (f) Price strategy (n = 22) | Impact of level of remoteness on price of healthy foods 35, 36, 37, 39, 50, 55, 75, 76, 77 | 9 | Comparison of the price of healthy and unhealthy foods in remote communities 61 | 1 |

| Impact of area socioeconomic status on food prices 37, 38, 40, 41, 42, 45, 49, 50, 53, 55, 77, 78, 79 | 13 | Comparison of the price of unhealthy foods/diet with healthy foods/diet 78, 81 | 2 | |

| Impact of food outlet type on food prices 43, 45, 49, 75, 77, 79, 80 | 7 | Change in price of unhealthy foods 50 | 1 | |

| Change in price of healthy foods 34, 35, 50, 55, 79, 80 | 6 | |||

| Impact of price on food choice 40 | 1 | |||

| Impact of perceived price on food choice 40 | 1 | |||

| (g) Price sensitivity and elasticity (n = 4) | Impact of price reductions on purchases of healthy foods 48, 75, 82, 83 | 4 | ||

| (h) Price promotions (n = 0) | – | – | ||

| Placement (n = 6) | ||||

| (i) In‐store location (n = 4) | Prevalence of healthy food displays at checkouts 86 | 1 | Prevalence of unhealthy food displays at checkouts, island bins and ends‐of‐aisles 26, 85, 86, 87 | 4 |

| (j) Shelf location (n = 6) | Impact of area socioeconomic status on shelf location of healthy foods 88 | 1 | Shelf location of unhealthy foods 26, 85, 86, 89 | 4 |

| Shelf space allocated to healthy foods 87 | 1 | Impact of area socioeconomic status on shelf location of unhealthy foods 88, 89 | 2 | |

| Shelf space allocated to unhealthy food 87 | 1 | |||

| Promotion (n = 16) | ||||

| (k) Health messages (n = 7) | Prevalence of health messages on packaging of healthy foods 37, 69 | 2 | Prevalence of health messages on packaging of unhealthy foods 64, 69, 90 | 3 |

| Implementation of health messages in remote community stores 47 | 1 | |||

| Consistency of front‐of‐pack health messages with dietary guidelines 91, 92 | 2 | |||

| (l) Promotions targeting children (n = 4) | Changes parents shopping with children would like implemented in 2supermarkets 93 | 1 | Marketing techniques used to promote unhealthy foods to children 62, 63, 64 | 3 |

| Prevalence of promotion of unhealthy foods to children 62 | 1 | |||

| (m) Other promotions (n = 6) | Use of promotional signage to identify nutritious foods 83, 94 | 2 | Prevalence of unhealthy foods in store external displays 86 | 1 |

| Impact of supermarket health promotion interventions 95, 96, 109 | 3 | |||

| Level of store support for supermarket health promotion interventions 95, 96 | 2 | |||

Product

Forty studies examined the domain of product (Table 4). Nutritional quality of food products was assessed most often (18/40), followed by product availability and quality (17/40), design of products and packaging (5/40), product assortment (6/40) and provision of supermarket own brand products (3/40).

Product availability and quality

Studies that examined this subdomain reported on the impact of geographic locality with regard to remoteness 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, area‐level socioeconomic status (SES) 38, 40, 41, 42, type of food outlet 38, 43, 44, 45 and interventions or policies 46, 47 on availability or quality of healthy food. Most used market basket surveys for data collection 34, 35, 36, 38, 41, 44, 45, 48, 49, 50. To reduce subjectivity when evaluating quality of fruit and vegetables, standardized quality assessment criteria were used by each study, although they were not all the same 38, 39, 49. Two studies evaluated the impact of actual and perceived availability of healthy foods in supermarkets on purchasing choices 40, 51. In relation to unhealthy foods, the availability of takeaway foods and sugar‐sweetened drinks, crisps and pastries was examined in metropolitan and rural regions 44, 52.

Product assortment

Studies examined the variety of healthy or unhealthy foods available within retail food outlets 38, 42, 49, 53, 54, 55. Assessments of healthy foods included availability of fruits and vegetables across different levels of area SES in Melbourne 53, Sydney 49 and Queensland 38; level of remoteness in New South Wales 55; and by type of food outlet in Brisbane 42. One study assessed the variety of unhealthy snack foods and drinks available in a Melbourne supermarket 54.

Design of products and packaging

Changes in the pack size of yogurts and dairy desserts over time were assessed 56. Recommended serving sizes on packaging of unhealthy foods were also assessed, including on single serve size packs of confectionery 54, 57. Provision of nutrition information in fast food outlets has been monitored over time, along with accessibility of the information 58, 59.

Nutritional quality

Nutritional quality of foods available in consumer nutrition environments was the most studied product subdomain. However, the way nutritional quality was defined differed by study. Examination of nutritional quality of foods in remote communities identified the prevalence of nutritionally poor foods such as refined carbohydrates 60 and the contribution of these foods to community dietary energy availability 61. The impact of store managers on nutrient intake of remote communities was evaluated 47.

Prevalence of healthy and unhealthy child‐orientated products was examined by a number of studies 62, 63, 64, 65, 66. This included identifying packaging with child‐orientated promotional characters 62, 63, 64 and products with sportspersons, celebrities or movie tie‐ins 63. The proportion of child‐orientated products that had been reformulated between 2009 and 2011 was assessed for any improvement in nutritional quality 65. Children's menu items from fast food outlets were evaluated by country and across companies 66.

Classification of packaged foods as healthy and unhealthy was reported 28, 54, 57, 67, 68. Nutrient profiling models utilized included the Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) Nutrient Profiling Scoring criterion, which is used to determine whether a food is suitable to make a health claim 28, 68, 69; the New South Wales School Canteen criteria, criteria developed for an Australian food company, and the United Kingdom Traffic Light criteria 54; the Health Star Rating front‐of‐pack labelling device scores 67; and the Australian Dietary Guidelines 57, 68. Changes in energy, total fat and protein content of yogurts and dairy desserts were assessed over time 56. The nutritional quality of child‐orientated foods promoted as healthy was evaluated 68.

Studies reporting nutrient reduction in processed foods all focused on sodium 70, 71, 72. Progress made towards achieving Australian government‐led sodium targets was assessed for bread, breakfast cereals, processed meats 70, pasta sauce 71 and a range of products spanning 15 food categories 72.

Provision of supermarket own brands

Two studies evaluated the nutritional quality of supermarket own brand foods in comparison with branded foods 72, 73. One study analysed products for differences between serve size, energy, total fat, saturated fat and sodium for supermarket own brand and brands 73. A more recent study evaluated differences in mean sodium content of supermarket own brand products from different supermarket chains and brands 72. The cost of supermarket own brand foods was compared with the branded equivalent 74.

Price

Twenty‐six studies examined the domain of price. Almost all studies (22/26) evaluated pricing strategy; few reported on the impact of price changes on consumer purchases (4/26); and none investigated price promotions.

Pricing strategy

Most studies reporting outcomes in this subdomain investigated impact of level of remoteness 35, 36, 37, 39, 50, 55, 75, 76, 77, area SES 37, 38, 40, 41, 42, 45, 49, 50, 53, 55, 77, 78, 79 or food outlet type 43, 45, 49, 75, 77, 79, 80 on the price of healthy foods. These studies compared the cost of healthy foods in rural and remote communities to metropolitan areas 35, 36, 39, 75, 76 and by increasing geographic isolation 36, 39, 50, 55. The price of branded products was compared with supermarket own brands 74; packaged foods were compared with fresh fruit and vegetables 75 and dairy 39; and the price of folate‐fortified products was assessed 37. Food prices were compared by area SES in Melbourne 53, Sydney 49, Brisbane 42, 78, Adelaide 41, 45, New South Wales 55, Queensland 38, Illawarra in New South Wales 79 and Victoria 50, 77. Comparisons of food prices were conducted, including in supermarket chains and independent stores in rural Victoria 43, 77 and rural New South Wales 79, 80; discount supermarkets, supermarket chains and independent stores in Sydney 49; and online and in‐store in Darwin 75.

Comparison of the price of healthy and unhealthy foods or dietary patterns was conducted by calculating the cost per kilojoule of foods available in a remote community 61 and for fast food menu items 81 and by using a market basket survey 78. A number of studies evaluated changes in the price of healthy foods over time using market basket surveys 34, 35, 50, 55, 79, 80. One study evaluated the association of actual and perceived food prices with food choices 40.

Price sensitivity and elasticity

Four studies reported the impact of price reductions on purchases of healthy foods 48, 82, 83, 84. The randomized controlled trial reported by two studies assigned shoppers to a skill‐building group, price‐reduction group, a combined skill‐building and price‐reduction group or a control group. Behaviour‐change outcomes 48, 82 and intervention cost‐effectiveness 82 were reported. A stepped‐wedge randomized controlled trial conducted in remote community stores in the Northern Territory examined the effectiveness of a price discount on purchases with and without consumer education 83. A natural experiment utilized mixed methods to evaluate the impact of four price discount strategies in remote community stores 84.

Placement

Only six studies reported aspects of the placement domain, including evaluations of shelf location, and size or prominence of product displays (6/6), and the physical location of products in stores (4/6).

In‐store location

Studies assessed the prevalence of snack food displays at supermarket checkouts, island bins and end‐of‐aisle displays 26, 85, 86, 87. Impact of area SES on in‐store location of snack foods was assessed 85. Displays of fruit and vegetables at checkouts were also reported 86.

Shelf location

Impact of area SES 88 and geographic location 87 on the amount of shelf space allocated to fruits and vegetables was investigated. Prominence of snack food displays was investigated at supermarket checkouts 26, including evaluating whether displays were within children's reach 86. The most prominent snack food on display at supermarkets was identified 85, along with physical measurement of snack food aisle lengths 26 and island bin snack displays 85. The association between the proportion of shelf space allocated to unhealthy foods and the amount purchased was reported by one study 89.

The impact of area SES on position and prominence of foods was assessed by two studies 88, 89. Two studies reported the amount of supermarket shelf space for snack foods as well as fruits and vegetables by area SES 88 and by geographic location 87. The association between purchases and shelf space allocated to unhealthy foods was evaluated by area SES 89.

Promotion

Sixteen studies investigated aspects of the promotion domain. Health messages on packaging or signage received the most attention (7/16), followed by packaging promotions targeting children (4/16) and other types of promotions including signage, shelf labelling and product samples (6/16).

Health messages

Prevalence of health messages on healthy and unhealthy foods was reported by most of the studies within this subdomain 37, 64, 69, 90. Evaluation of the prevalence of health claims included use of the folate‐neural tube defect health claim 37 and whether or not foods met the draft FSANZ Nutrient Profiling Scoring Criterion, which is now used to determine whether a food is suitable to make a health claim 69. The prevalence of snack foods featuring the food industry's voluntary Daily Intake Guide front‐of‐pack label, along with level of compliance with guidelines for its use, was evaluated 90. Health messages on the front of packaging were assessed for consistency with the Australian Dietary Guidelines 91, 92. Finally, prevalence of statements and claims about health and nutrition on foods identified as child orientated was reported 64.

One study evaluated implementation of health promotion messages in remote community stores and associated dietary improvements for the community 47.

Promotions targeting children

Studies identified and described the marketing techniques used to promote packaged foods to children in supermarkets 62, 63, 64. One study identified prevalence of packaging that used characters from TV, films and cartoons to appeal to children 62, which was reinforced by a more recent study that described 16 techniques employed to appeal to children 64. Another study investigated use of these characters on healthy or unhealthy products and whether the manufacturers were signatories to the food industry's voluntary children's marketing code 63. Changes parents shopping with children would like implemented in supermarkets were also described 93.

Other promotions

The studies in this subdomain described a range of outcomes related to other promotions, including use of promotional signage to identify nutritious foods in community stores 94 and communicate a price discount on fruit and vegetables 83; level of store support and impact of supermarket health promotion interventions 95, 96; and promotion of snack foods outside of stores 86.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to identify and summarize the domains of the consumer nutrition environment (i.e. product, price, placement and promotion) that have been examined in Australian peer‐reviewed research. This is an emerging field of research in Australia, as evidenced by the fact that most of the 66 studies identified were published from 2011 onwards. The domain most studied was product, followed by price and then promotion. Few studies examined placement, and no studies addressed all four domains of product, price, placement and promotion. Indeed, 10 of the 13 subdomains were examined by seven or less studies, typically reporting mixed findings. Gaps in knowledge were evident across all four domains of consumer nutrition environments. These gaps, along with recommendations to address them, are presented below.

The first recommendation is to develop consistent observational methodology. Development of standardized observation tools that are appropriate for use in Australian consumer nutrition environments is a priority. Within each subdomain, a lack of consistency amongst the observation tools utilized was found, which makes comparisons of study findings difficult. Whilst the selection of survey instrument needs to be appropriate to the purpose of the assessment 97 and the specific context to be investigated (e.g. remote or regional communities compared with urban areas), it is recommended that researchers select an existing quality assessed tool where possible 22. Furthermore, some studies lacked details of who collected the data in the retail outlets or how the information was recorded or validated 62, 65, 70, 72, 89.

To reduce subjectivity when evaluating nutritional quality, or defining food as healthy or unhealthy, standardized criteria should be applied. In Australia, criteria could include food group classification consistent with the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating 98, the principles for identifying ‘discretionary foods’ 99 or FSANZ's nutrient profiling model 100, which classifies products according to whether they are suitable to carry health claims on packaging.

The work of INFORMAS aimed to standardize food environments monitoring in diverse countries and settings, to assist public and private sector actions to create healthy food environments and reduce obesity, non‐communicable diseases and their inequalities 9. Table S2 identifies the INFORMAS modules relevant to each consumer nutrition environment subdomain, to assist with development of consistent methodology. Future research should also clearly describe the setting under examination when reporting findings, including identifying the food outlet type and location, to build understanding of specific consumer nutrition environments. A number of studies that described the nutritional quality of the Australian food supply were excluded from this scoping review because of lack of information on the specific consumer nutrition environments under investigation.

The second recommendation is to consider consumer nutrition environments in rural and remote communities. Few studies were conducted in remote community stores 39, 46, 47, 60, 61, 75, 83, 84, 94, so little is currently known about these environments. These studies have examined only six of the 13 subdomains: product availability and quality 39, 46, 47, nutritional quality 47, 60, 61, price strategy 39, 61, 75, price sensitivity and elasticity 83, 84, health messages 47 and other promotions 83, 94, and their findings cover only nine of the 53 identified themes. Australians living in rural and remote regions are more likely to be overweight or obese resulting in a higher incidence of non‐communicable diseases 101; thus, food retail outlets present in these communities hold great potential as settings for health promotion interventions 39.

The third recommendation is to understand consumer nutrition environments in different food retail outlet types and under‐researched subdomains. This scoping review found that supermarkets were the most studied type of food retail outlet, followed by community stores, with few studies of fast food outlets. Whilst more research is needed within each of these settings, there are many food outlet types that are yet to be examined in Australia, such as convenience stores, service stations, greengrocers, cafes, restaurants, takeaway food outlets other than fast food chains and fresh food markets. Food environment research to date has included only a limited range of food outlets 102. International research suggests that consumer nutrition environment findings can vary by food outlet type 13; thus, more research within and across different food outlets is needed.

Under‐researched consumer nutrition environment subdomains include product assortment. Little is known about the amount of product choice available within consumer food environments. This is important because product assortment has been shown to influence consumers' food choice 12.

Few studies examined the packaging design of products. Packaging has been described as integral to the product 103, and packaging design includes size and format, as well as provision of nutrition information and recommended serving sizes 12. Because most food purchase decisions are made at the point of sale after only a few seconds 104, it is important to investigate which packaging design techniques make foods appealing within a consumer nutrition environment.

Provision of supermarket own brand products is another under‐researched area identified in this study. Supermarket own brand products are owned by retailers or wholesalers and sold privately in their own stores 105. Australian supermarket own brands are estimated to contribute 35% of grocery sales by 2020 106. However, little is known about them other than sodium content 72.

There is a gap in information about the impact of price changes on the healthfulness of consumer purchases. Priorities for research needed to fill this gap have been identified by Epstein et al., including examining which foods are most effective to target and whether health benefits are experienced by the subpopulations most in need 107.

There are no Australian studies that have reported prevalence or type of price promotions present in consumer nutrition environments, such as price reductions, multi‐buy offers or coupons.

Only four studies examined the presence of health messages on food packaging 64, 69, 91, 92, and one study reported on the compliance of voluntary labelling initiatives 90. Two of the studies considered whether health messages present on packaging were consistent with the recommendations of the Australian Dietary Guidelines 91, 92. More evidence of current practice is needed, along with analysis of other in‐store methods for communicating health, such as leaflets and signage.

Few studies have examined use of signage, banners, shelf labelling, samples and taste testing in food retail outlets 83, 86, 94, 95, 96. Investigation of the prevalence and impact of these promotions is needed.

The fourth recommendation is to build on the existing evidence in all four domains of product, price, placement and promotion. More research is needed to replicate and build upon the existing evidence base across all four domains. In particular, future research should focus on extending the evidence base within the subdomains of product availability and quality, pricing strategy, in‐store location and promotions targeting children.

Most of the studies reporting availability of healthy foods were market basket surveys 34, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41, 43, 45, 46, 49, 50. Whilst market basket surveys are ideal to assess community food security using cost and availability data, they may not be appropriate for evaluation of the ‘overall healthfulness’ of consumer nutrition environments because of the focus typically placed on provision of healthy foods. More studies are needed that describe the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods, using standardized definitions of what is healthy or unhealthy such as food group classifications consistent with the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating 98.

There was some evidence that food outlet type, but not area SES, can influence food price, so a clearer understanding of this across different food outlet types is needed. Few studies have investigated differences in the price of healthy and unhealthy foods 40, 61, 81. As price is a key strategy used by retailers to gain competitive advantage 108, building a greater understanding of how food purchase decisions are influenced through pricing strategy is important.

Placement of unhealthy snack foods and beverages has been investigated 26, 85, 86, 88, 89, but there is a gap in information about the in‐store location of displays of healthy products. Public health researchers have identified replacing highly visible displays of unhealthy snacks with healthy foods as an opportunity for reducing snack food purchases 12, so more information about in‐store location of displays of healthy and unhealthy foods is needed.

Whilst promotion of unhealthy foods to children was examined by a number of studies 62, 63, 64, 93, more evidence is needed to build a greater understanding of the in‐store marketing techniques used, the product categories of interest and the interventions needed to prevent these practices from adversely affecting children's diets.

The final recommendation is to determine effective policy and store‐based interventions for healthy eating. This scoping review identified eight store‐based intervention studies that aimed to improve purchasing or dietary behaviour, conducted in supermarkets and remote Northern Territory community stores 46, 48, 82, 83, 94, 95, 96, 109. A number of successful strategies were identified, including a 20% price reduction for fruit and vegetables in metropolitan supermarkets, which led to increased purchases over the intervention period, although this was not maintained afterwards 48; a 20% price reduction for fruit and vegetables in remote community stores led to increased purchases, which was further enhanced by consumer education 83; a nutrition education programme encouraging purchases of low‐fat dairy, fruit, vegetables, bread and cereals achieved changes in self‐reported food purchasing behaviour 95; a behaviour change intervention led to increased vegetable consumption 109; an introduction of a nutrition policy across five remote community stores led to dietary improvements in the communities that most complied 94; and a diabetes health promotion intervention led to increased range and availability of healthy foods in a remote community store and increased community‐level purchases of healthier food 46.

Whilst identification of these strategies is encouraging, studies have only reported findings from three consumer nutrition environment subdomains of product availability and quality 46, price sensitivity and elasticity 48, 82, 83 and other promotions 94, 95, 96, 109, spanning five of the 53 themes identified. Interventions need to be informed by observational studies that clearly identify the attributes of consumer nutrition environments that are a priority for change and measure the extent of the problem. Building the evidence base across all four domains of product, price, placement and promotion will help to determine which policies and interventions might be effective at developing consumer nutrition environments supportive of healthy eating. Evaluation of in‐store interventions will be essential, including identifying unintended consequences, to support positive changes in food purchasing and dietary behaviour.

This is the first study to summarize the existing peer‐reviewed literature relating to consumer nutrition environments in Australia and the first review to include all four domains of product, placement, price and promotion. This study applied the conceptual model developed by Glanz et al. 11 and followed the established five‐step protocol for scoping reviews 31. In addition, the main findings for each of the themes identified in Australian consumer nutrition environment studies have been summarized in the Supporting Information. Limitations include the possibility that the search strategy did not capture all relevant documents and the current study has therefore overlooked some existing knowledge on Australian consumer nutrition environments. This risk was minimized by scanning the reference lists and citations of included studies, the authors' knowledge of the research field and the search terms that were based on prior studies. Consistent with the scoping review protocol, quality of included studies was not evaluated 31.

This scoping review identified which domains of the consumer nutrition environment have been examined in Australian peer‐reviewed research to date. Across 13 consumer nutrition environment subdomains, 53 themes were identified. The most common were assessment of the impact of area SES (13/66), remoteness (9/66) and food outlet type (7/66) on healthy food prices; change in price of healthy foods over time (6/66); variety of healthy foods available (5/66); and prevalence of unhealthy child‐orientated products (5/66). A large number of gaps in knowledge were identified. The key priorities for future Australian research are to (1) develop consistent observational methodology, (2) consider consumer nutrition environments in rural and remote communities, (3) understand consumer nutrition environments in different food retail outlet types such as food service and under‐researched subdomains such as price promotions, (4) build on the existing evidence in all four domains of product, price, placement and promotion and (5) determine effective policy and store‐based interventions for healthy eating. Research consistent with these recommendations should assist with creating Australian consumer nutrition environments supportive of healthy choices and increase population adherence to dietary guidelines to prevent and control obesity, non‐communicable diseases and their inequalities. In recognition of the country‐specific nature of food environments, other countries may also benefit from conducting similar scoping reviews.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

G. S. A. T. is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Research Fellowship (no. 1073233). C. E. P. has a Healthway Health Promotion Research Training Scholarship (no. 24124) and is supported through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Supporting information

Table S1. Themes identified in Australian consumer nutrition environment studies, with main findings

Table S2. Recommendations for monitoring consumer nutrition environments, adapted from INFORMAS1 and Glanz and colleagues2,3

Pulker, C. E. , Thornton, L. E. , and Trapp, G. S. A. (2018) What is known about consumer nutrition environments in Australia? A scoping review of the literature. Obesity Science & Practice, 4: 318–337. 10.1002/osp4.275.

References

- 1. Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 386: 2287–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Health and Medical Research Council . Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey . Nutrition First Results – Foods and Nutrients, 2011‐12, cat. no. 4364.0.55.007. ABS: Canberra, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey . Consumption of Food Groups from the Australian Dietary Guidelines, 2011‐12, cat. no. 4364.0.55.012. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization . Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. World Health Organization: Geneva, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization . The United Nations General Assembly Proclaims the Decade of Action on Nutrition. World Health Organization: USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson‐O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health 2008; 29: 253–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hawkes C, Jewell J, Allen K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet‐related non‐communicable diseases: the NOURISHING framework. Obes Rev 2013; 14: 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Swinburn B, Sacks G, Vandevijvere S, et al. INFORMAS (International Network for Food and Obesity/non‐communicable diseases Research, Monitoring and Action Support): overview and key principles. Obes Rev 2013: 14: 1–14: 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adam A, Jensen JD. What is the effectiveness of obesity related interventions at retail grocery stores and supermarkets? – a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot 2005; 19: 330–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Glanz K, Bader MD, Iyer S. Retail grocery store marketing strategies and obesity: an integrative review. Am J Prev Med 2012; 42: 503–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ni Mhurchu C, Vandevijvere S, Waterlander W, et al. Monitoring the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods and non‐alcoholic beverages in community and consumer retail food environments globally. Obes Rev 2013; 14: 108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cameron AJ, Charlton E, Ngan WW, Sacks G. A systematic review of the effectiveness of supermarket‐based interventions involving product, promotion, or place on the healthiness of consumer purchases. Curr Nutr Rep 2016: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Escaron AL, Meinen AM, Nitzke SA, Martinez‐Donate AP. Supermarket and grocery store‐based interventions to promote healthful food choices and eating practices: a systematic review. Prev Chronic Dis 2013; 10: E50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liberato SC, Bailie R, Brimblecombe J. Nutrition interventions at point‐of‐sale to encourage healthier food purchasing: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014; 14: 919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bucher T, Collins C, Rollo ME, et al. Nudging consumers towards healthier choices: a systematic review of positional influences on food choice. Br J Nutr 2016; 115: 2252–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place 2012; 18: 1172–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Engler‐Stringer R, Le H, Gerrard A, Muhajarine N. The community and consumer food environment and children's diet: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014; 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gustafson A, Hankins S, Jilcott S. Measures of the consumer food store environment: a systematic review of the evidence 2000–2011. J Community Health 2012; 37: 897–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kirkpatrick SI, Reedy J, Butler EN, et al. Dietary assessment in food environment research: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2014; 46: 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Glanz K, Johnson L, Yaroch AL, Phillips M, Ayala GX, Davis EL. Measures of retail food store environments and sales: review and implications for healthy eating initiatives. J Nutr Educ Behav 2016; 48: 280, e1–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lewis M, Lee A. Costing ‘healthy’ food baskets in Australia – a systematic review of food price and affordability monitoring tools, protocols and methods. Public Health Nutr 2016: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Osei‐Assibey G, Dick S, Macdiarmid J, et al. The influence of the food environment on overweight and obesity in young children: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2012; 2: e001538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cummins S, Macintyre S. Food environments and obesity – neighbourhood or nation? Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35: 100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thornton LE, Cameron AJ, McNaughton SA, et al. Does the availability of snack foods in supermarkets vary internationally? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013; 10: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poelman MP, Eyles H, Dunford E, et al. Package size and manufacturer‐recommended serving size of sweet beverages: a cross‐sectional study across four high‐income countries. Public Health Nutr 2016; 19: 1008–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ni Mhurchu C, Brown R, Jiang Y, Eyles H, Dunford E, Neal B. Nutrient profile of 23 596 packaged supermarket foods and non‐alcoholic beverages in Australia and New Zealand. Public Health Nutr 2015: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Charlton EL, Kähkönen LA, Sacks G, Cameron AJ. Supermarkets and unhealthy food marketing: an international comparison of the content of supermarket catalogues/circulars. Prev Med 2015; 81: 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Minaker LM, Shuh A, Olstad DL, Engler‐Stringer R, Black JL, Mah CL. Retail food environments research in Canada: a scoping review. Can J Public Health 2016; 107: 4–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Social Research Methodology 2005; 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 32. The Joanna Briggs Institute . Reviewers' Manual: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute: Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 2010; 5: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harrison MS, Coyne T, Lee AJ, et al. The increasing cost of the basic foods required to promote health in Queensland. Med J Aust 2007; 186: 9–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harrison M, Lee A, Findlay M, Nicholls R, Leonard D, Martin C. The increasing cost of healthy food. Aust N Z J Public Health 2010; 34: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee AJ, Darcy AM, Leonard D, et al. Food availability, cost disparity and improvement in relation to accessibility and remoteness in Queensland. Aust N Z J Public Health 2002; 26: 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lawrence MA, Rutishauser IHE, Lewis JL. An analysis of the introduction of folate‐fortified food products into stores in Australia. Australian J Nutri Dietetics 1999; 56: 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Millichamp A, Gallegos D. Comparing the availability, price, variety and quality of fruits and vegetables across retail outlets and by area‐level socio‐economic position. Public Health Nutr 2013; 16: 171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pollard CM, Landrigan TJ, Ellies PL, Kerr DA, Lester ML, Goodchild SE. Geographic factors as determinants of food security: a Western Australian food pricing and quality study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2014; 23: 703–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Giskes K, Van Lenthe FJ, Brug J, Mackenbach JP, Turrell G. Socioeconomic inequalities in food purchasing: the contribution of respondent‐perceived and actual (objectively measured) price and availability of foods. Prev Med 2007; 45: 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wong KC, Coveney J, Ward P, et al. Availability, affordability and quality of a healthy food basket in Adelaide, South Australia. Nutrition & Dietetics 2011; 68: 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Winkler E, Turrell G, Patterson C. Does living in a disadvantaged area entail limited opportunities to purchase fresh fruit and vegetables in terms of price, availability, and variety? Findings from the Brisbane Food Study. Health Place 2006; 12: 741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Burns CM, Gibbon P, Boak R, Baudinette S, Dunbar JA. Food cost and availability in a rural setting in Australia. Rural Remote Health 2004; 4: 311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Innes‐Hughes C, Boylan S, King LA, Lobb E. Measuring the food environment in three rural towns in New South Wales, Australia. Health Promot J Austr 2012; 23: 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tsang A, Ndung'U MW, Coveney J, O'Dwyer L. Adelaide healthy food basket: a survey on food cost, availability and affordability in five local government areas in Metropolitan Adelaide, South Australia. Nutrition & Dietetics 2007; 64: 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tyrrell M, Lynch P, Wakerman J. Laramba Diabetes Project: an evaluation of a participatory project in a remote Northern Territory community. Health Promot J Austr 2003; 14: 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee AJ, Bonson APV, Powers JR. The effect of retail store managers on Aboriginal diet in remote communities. Aust N Z J Public Health 1996; 20: 212–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ball K, McNaughton SA, Le HN, et al. Influence of price discounts and skill‐building strategies on purchase and consumption of healthy food and beverages: outcomes of the Supermarket Healthy Eating for Life randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2015; 101: 1055–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Crawford B, Byun R, Mitchell E, Thompson S, Jalaludin B, Torvaldsen S. Socioeconomic differences in the cost, availability and quality of healthy food in Sydney. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017: n/a–n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Palermo C, McCartan J, Kleve S, Sinha K, Shiell A. A longitudinal study of the cost of food in Victoria influenced by geography and nutritional quality. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016; 40: 270–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Inglis V, Ball K, Crawford D. Socioeconomic variations in women's diets: what is the role of perceptions of the local food environment? J Epidemiol Community Health 2008; 62: 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McManus A, Brown G, Maycock B. Western Australian Food Security Project. BMC Public Health 2007; 7: 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ball K, Timperio A, Crawford D. Neighbourhood socioeconomic inequalities in food access and affordability. Health Place 2009; 15: 578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Walker KZ, Woods JL, Rickard CA, Wong CK. Product variety in Australian snacks and drinks: how can the consumer make a healthy choice? Public Health Nutr 2008; 11: 1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chapman K, Kelly B, Bauman A, Innes‐Hughes C, Allman‐Farinelli M. Trends in the cost of a healthy food basket and fruit and vegetable availability in New South Wales, Australia, between 2006 and 2009. Nutrition & Dietetics 2014; 71: 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Walker KZ, Woods J, Ross J, Hechtman R. Yoghurt and dairy snacks presented for sale to an Australian consumer: are they becoming less healthy? Public Health Nutr 2010; 13: 1036–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Haskelberg H, Neal B, Dunford E, et al. High variation in manufacturer‐declared serving size of packaged discretionary foods in Australia. Br J Nutr 2016; 115: 1810–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wellard L, Glasson C, Chapman K, Miller C. Fast facts: the availability and accessibility of nutrition information in fast food chains. Health Promot J Austr 2011; 22: 184–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wellard L, Havill M, Hughes C, Watson WL, Chapman K. The availability and accessibility of nutrition information in fast food outlets in five states post‐menu labelling legislation in New South Wales. Aust N Z J Public Health 2015; 39: 546–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brimblecombe J, Liddle R, O'Dea K. Use of point‐of‐sale data to assess food and nutrient quality in remote stores. Public Health Nutr 2013; 16: 1159–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brimblecombe JK, O'Dea K. The role of energy cost in food choices for an Aboriginal population in northern Australia. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 549–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chapman K, Nicholas P, Banovic D, Supramaniam R. The extent and nature of food promotion directed to children in Australian supermarkets. Health Promot Int 2006; 21: 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hebden L, King L, Kelly B, Chapman K, Innes‐Hughes C. A menagerie of promotional characters: promoting food to children through food packaging. J Nutr Educ Behav 2011; 43: 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mehta K, Phillips C, Ward P, Coveney J, Handsley E, Carter P. Marketing foods to children through product packaging: prolific, unhealthy and misleading. Public Health Nutr 2012; 15: 1763–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Savio S, Mehta K, Udell T, Coveney J. A survey of the reformulation of Australian child‐oriented food products. BMC Public Health 2013; 13: 836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hobin E, White C, Li Y, Chiu M, O'Brien MF, Hammond D. Nutritional quality of food items on fast‐food ‘kids' menus’: comparisons across countries and companies. Public Health Nutr 2014; 17: 2263–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wu JH, Neal B, Trevena H, et al. Are gluten‐free foods healthier than non‐gluten‐free foods? An evaluation of supermarket products in Australia. Br J Nutr 2015; 114: 448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Meloncelli NJL, Pelly FE, Cooper SL. Nutritional quality of a selection of children's packaged food available in Australia. Nutrition & Dietetics 2016; 73: 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hughes C, Wellard L, Lin J, Suen KL, Chapman K. Regulating health claims on food labels using nutrient profiling: what will the proposed standard mean in the Australian supermarket? Public Health Nutr 2013; 16: 2154–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Trevena H, Neal B, Dunford E, Wu JH. An evaluation of the effects of the Australian Food and Health Dialogue targets on the sodium content of bread, breakfast cereals and processed meats. Nutrients 2014; 6: 3802–3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Trevena H, Dunford E, Neal B, Webster J. The Australian Food and Health Dialogue – the implications of the sodium recommendation for pasta sauces. Public Health Nutr 2014; 17: 1647–1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Trevena H, Neal B, Dunford E, Haskelberg H, Wu JH. A comparison of the sodium content of supermarket private‐label and branded foods in Australia. Nutrients 2015; 7: 7027–7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Cleanthous X, Mackintosh A‐M, Anderson S. Comparison of reported nutrients and serve size between private label products and branded products in Australian supermarkets. Nutrition & Dietetics 2011; 68: 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chapman K, Innes‐Hughes C, Goldsbury D, Kelly B, Bauman A, Allman‐Farinelli M. A comparison of the cost of generic and branded food products in Australian supermarkets. Public Health Nutr 2013; 16: 894–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ferguson M, O'Dea K, Chatfield M, Moodie M, Altman J, Brimblecombe J. The comparative cost of food and beverages at remote Indigenous communities, Northern Territory, Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016; 40: S21–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ward PR, Coveney J, Verity F, Carter P, Schilling M. Cost and affordability of healthy food in rural South Australia. Rural Remote Health 2012; 12: 1938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Palermo CE, Walker KZ, Hill P, McDonald J. The cost of healthy food in rural Victoria. Rural Remote Health 2008; 8: 1074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lee AJ, Kane S, Ramsey R, Good E, Dick M. Testing the price and affordability of healthy and current (unhealthy) diets and the potential impacts of policy change in Australia. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Williams P, Hull A, Kontos M. Trends in affordability of the Illawarra Healthy Food Basket 2000–2007. Nutrition & Dietetics 2009; 66: 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Williams P, James Y, Kwan J. The Illawarra Healthy Food Price Index 2. Pricing methods and index trends from 2000–2003. Nutrition & Dietetics 2004; 61: 208–214. [Google Scholar]