As a partner antimalarial for artemisinin drug-based combination therapy (ACT), piperaquine (PQ) can be metabolized into two major metabolites, including piperaquine N-oxide (M1) and piperaquine N,N-dioxide (M2). To better understand the antimalarial potency of PQ, the antimalarial activity of the PQ metabolites (M1 and M2) was studied in vitro (in Plasmodium falciparum strains Pf3D7 and PfDd2) and in vivo (in the murine species Plasmodium yoelii) in this study.

KEYWORDS: piperaquine, metabolite, antiplasmodial activity, healthy subjects, pharmacokinetics

ABSTRACT

As a partner antimalarial for artemisinin drug-based combination therapy (ACT), piperaquine (PQ) can be metabolized into two major metabolites, including piperaquine N-oxide (M1) and piperaquine N,N-dioxide (M2). To better understand the antimalarial potency of PQ, the antimalarial activity of the PQ metabolites (M1 and M2) was studied in vitro (in Plasmodium falciparum strains Pf3D7 and PfDd2) and in vivo (in the murine species Plasmodium yoelii) in this study. The recrudescence and survival time of infected mice were also recorded after drug treatment. The pharmacokinetic profiles of PQ and its two metabolites (M1 and M2) were investigated in healthy subjects after oral doses of two widely used ACT regimens, i.e., dihydroartemisinin plus piperaquine phosphate (Duo-Cotecxin) and artemisinin plus piperaquine (Artequick). Remarkable antiplasmodial activity was found for PQ (50% growth-inhibitory concentration [IC50], 4.5 nM against Pf3D7 and 6.9 nM against PfDd2; 90% effective dose [ED90], 1.3 mg/kg of body weight), M1 (IC50, 25.5 nM against Pf3D7 and 38.7 nM against PfDd2; ED90, 1.3 mg/kg), and M2 (IC50, 31.2 nM against Pf3D7 and 33.8 nM against PfDd2; ED90, 2.9 mg/kg). Compared with PQ, M1 showed comparable efficacy in terms of recrudescence and survival time and M2 had relatively weaker antimalarial potency. PQ and its two metabolites displayed a long elimination half-life (∼11 days for PQ, ∼9 days for M1, and ∼4 days for M2), and they accumulated after repeated administrations. The contribution of the two PQ metabolites to the efficacy of piperaquine as a partner drug of ACT for the treatment of malaria should be considered for PQ dose optimization.

INTRODUCTION

Artemisinin drugs (dihydroartemisinin, artemether, and artesunate) are effective against both chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum (1). To avoid the rapid development of drug resistance, artemisinin drugs are recommended to be used in the clinic as part of combination treatment therapies (artemisinin drug-based combination therapy [ACT]); i.e., the artemisinin drug provides the major contribution to the rapid clearance of P. falciparum, whereas the concomitant partner antimalarial with a prolonged half-life is involved in eliminating residual parasites (2, 3). Though the artemisinin derivatives are generally effective, it has been observed that the effectiveness of the main artemisinin drugs in Southeast Asia has been diminished due to parasite resistance (4, 5). These findings highlight the necessity and importance of the partner drugs in ACT. Several important partner drugs are derived from the quinoline ring system, such as piperaquine {PQ; 1,3-bis-[1-(7-chloroquinolyl-4)-piperazinyl-1]-propane; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material} (6). PQ has been suggested to act on the blood stages of the parasite's life cycle. The exact mechanism of action is unknown for PQ. It is thought to be similar to that of a structural analogue, chloroquine (CQ), which inhibits hemozoin formation, with the corresponding increase in free heme being correlated with parasite death (7).

PQ monotherapy was used both for prophylaxis and for treatment in China in the 1970s and 1980s, until resistance to the drug emerged (8). Two promising ACTs are the fixed-dose dihydroartemisinin (DHA) plus PQ (Duo-Cotecxin) and artemisinin (QHS) plus PQ (QHS-PQ), which are well tolerated and highly effective in the treatment of P. falciparum malaria. DHA-PQ is on both the WHO Malaria Treatment Guidelines and WHO List of Essential Medicines.

Despite the long history of PQ use, its pharmacokinetic properties have been characterized only in recent years. PQ displays a large volume of distribution (∼700 liters/kg of body weight), a low oral clearance (CL/F; 29 to 109 liters/h), and a long terminal elimination half-life (t1/2; about 1 month) (6, 9, 10). The absolute oral bioavailability of PQ was approximately 50% in rat (11). Several metabolites of PQ have been found in rat (11) and human (12, 13), and these mainly include two N-oxidation products (metabolite M1 with a molecular weight [MW] of 550 and metabolite M2 with an MW of 566; Fig. S1) and a carboxylic acid metabolite (MW, 319). Another two minor hydroxylated products were also detected in human urine (12). Metabolites containing the 7-chloro group in their structures were proposed to be bioactive, based on a previous study of their structure-activity relationships (14), and the carboxylic acid metabolite has been proven to show potent antimalarial activity. The antimalarial efficacy of the other two metabolites (M1 and M2) remains unknown. The pharmacokinetic profiles of PQ and its metabolites could be of great importance in determining the clinical efficacy and safety outcomes of PQ; however, related information was limited only to the pharmacokinetics of the parent drug PQ and its metabolites in rats (15) or in only one human subject (16).

In this study, the antimalarial potency of the PQ metabolites (M1 and M2) was studied in vitro (in chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum strain Pf3D7 and chloroquine-resistant strain PfDd2) and in vivo (in the murine species Plasmodium yoelii). The recrudescence and survival time of infected mice were also recorded after drug treatment. The pharmacokinetic profiles of PQ and its two metabolites (M1 and M2) were investigated in humans after oral doses of two widely used ACT regimens, i.e., dihydroartemisinin plus piperaquine and artemisinin plus piperaquine.

RESULTS

PQ and its metabolites showed antiplasmodial activity against chloroquine-sensitive strain Pf3D7 and chloroquine-resistant strain PfDd2.

The positive control, chloroquine (CQ), showed consistent antiplasmodial activity against Pf3D7 (50% growth-inhibitory concentration [IC50], 14.9 nM) and PfDd2 (IC50, 80.4 nM). PQ also displayed remarkable antiplasmodial activity against both malaria parasite strains, with IC50s of 4.5 nM (Pf3D7) and 6.9 nM (PfDd2). Comparable in vitro antiplasmodial activities (IC50, ∼30 nM) were observed for the two PQ metabolites (M1 and M2). Table 1 shows the IC50s and IC90s of PQ and its metabolites.

TABLE 1.

Antiplasmodial activity of PQ and its two N-oxidation metabolites (M1 and M2) against the Pf3D7 strain, PfDd2 strain, and murine species Plasmodium yoeliia

| Test drug |

Pf3D7 |

PfDd2 |

P. yoelii |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (nM) | IC90 (nM) | IC50 (nM) | IC90 (nM) | ED50 (mg/kg) | ED90 (mg/kg) | |

| CQ | 14.95 ± 1.22 | 18.99 ± 2.79 | 80.39 ± 21.81 | NA | 0.56 ± 0.14 | 1.66 ± 0.35 |

| PQ | 4.46 ± 0.28 | 7.93 ± 0.20 | 6.85 ± 0.78 | NA | 0.54 ± 0.09 | 1.27 ± 0.12 |

| M1 | 25.54 ± 1.39 | 41.33 ± 4.81 | 38.71 ± 3.64 | NA | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 1.26 ± 0.08 |

| M2 | 31.22 ± 0.16 | NA | 33.82 ± 5.37 | NA | 1.91 ± 0.02 | 2.89 ± 0.68 |

M1 is PQ N-oxide, and M2 is PQ N,N-dioxide. Chloroquine (CQ) was used as a positive-control model drug. In vivo experiments consisted of 3 to 5 doses with 9 mice/dose. ED50 and ED90 were calculated by Prism (GraphPad) software from a best-fit curve. NA, not acquired.

In vivo efficacy against Plasmodium yoelii.

The parasitemia of mice treated with any test drug (CQ, PQ, M1, or M2) was lower than that of vehicle-treated control mice at any dose. The positive-control model drug CQ showed remarkable antimalarial activity (50% effective dose [ED50], 0.6 mg/kg of body weight; ED90, 1.7 mg/kg), and a dose of 4.0 mg/kg/day CQ diminished P. yoelii parasitemia by 98.0% on day 4. PQ dose-response testing showed an ED50 value of 0.5 mg/kg and an ED90 of 1.3 mg/kg. No parasitemia was found in 7 out of 9 infected mice on day 4 after the treatment with a high dose of PQ (4 mg/kg). The metabolite M1 (PQ N-oxide) retained activity against P. yoelii similar to that of CQ or PQ, with an ED90 of 1.3 mg/kg. The other metabolite, M2 (PQ N,N-dioxide), showed relatively lower activity (ED50, 1.9 mg/kg; ED90, 2.9 mg/kg). PQ and its two metabolites displayed low ED50 and ED90 values, indicating that they are indeed orally efficacious. The dose-response curves for PQ and its metabolites are shown in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material, and their ED50 and ED90 values are shown in Table 1.

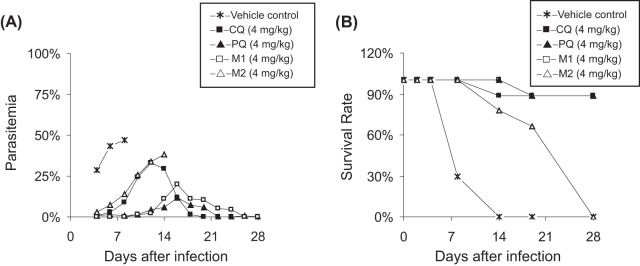

A single-dose toxicity evaluation was also performed using three mice in each case, and the general measures of animal well-being (weight and locomotor activity) were recorded. Using this crude screen, no evident toxicity was found for PQ and its metabolites at doses as high as 20-fold the ED50, suggesting a favorable safety margin. To test whether PQ and its metabolites could completely clear infection after repeated dosing, the recrudescence, survival time, and mortality of infected mice were also recorded (Fig. 1 and Table S1). When CQ was given to infected mice (2.0 mg/kg), the parasites could be suppressed by 91.7% on day 4, which increased to 98.0% at 4.0 mg/kg. The survival rate of infected mice was also improved (from 33.3% to 88.9%) on day 28. The 3-day treatment with PQ (4.0 mg/kg) reduced the P. yoelii parasitemia to less than 1.0% on day 4 postdosing, and 8 out of 9 mice could survive for at least 28 days without parasitemia. An equivalent dose of M1 led to a lower parasitemia of 0.04% on day 4 and a high curative rate (88.9%) on day 28. All infected mice survived for at least 14 days after a lower oral dose of M1 (2 mg/kg), but only 33.3% of mice could be totally cured on day 28 without parasitemia. The metabolite M2 was effective after 3 days of treatment, but with a higher curative dose of >4.0 mg/kg. Observable parasites were present in each group dosed with M2 (1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mg/kg), and all mice died over 3 weeks.

FIG 1.

Mean parasitemia (A) and survival rate (B) of P. yoelii-infected mice (n = 9) treated with the vehicle control, chloroquine (CQ; the positive-control model drug; 4 mg/kg), piperaquine (PQ; 4 mg/kg), or the piperaquine N-oxidation metabolites (M1, PQ N-oxide; M2, PQ N,N-dioxide; 4 mg/kg).

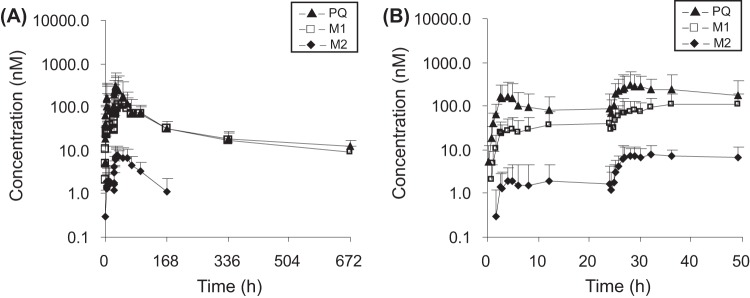

The PQ metabolites showed slow clearance in humans, which is similar to PQ.

The pharmacokinetic profiles of PQ and its metabolites were evaluated in humans after oral administrations of PQ in two dosing regimens (QHS-PQ and DHA-PQ). The pharmacokinetic properties of PQ after repeated oral administration in healthy subjects were characterized by multiple concentration peaks during the absorption phase and a multiphasic disposition with a long terminal half-life (∼11 days for PQ, ∼9 days for M1, and ∼4 days for M2), and they accumulated after repeated administrations. The mean plasma concentration-time profiles of PQ and its two metabolites in humans after oral administration of PQ are shown in Fig. 2 and 3. The pharmacokinetic parameters are given in Tables 2 and 3.

FIG 2.

Mean (+SD) plasma concentration-time profiles of piperaquine (PQ) and its N-oxidation metabolites (M1, PQ N-oxide; M2, PQ N,N-dioxide) in healthy Chinese subjects (n = 9) following a recommended two oral doses of QHS-PQ (a 125-mg/dose of artemisinin plus a 750-mg/dose of PQ) from 0 to 672 h (A) and from 0 to 50 h (B).

FIG 3.

Mean (+SD) plasma concentration-time profiles of piperaquine (PQ) and its N-oxidation metabolites (M1, PQ N-oxide; M2, PQ N,N-dioxide) in healthy Chinese subjects (n = 4) following a recommended four oral doses of DHA-PQ (an 80-mg/dose of dihydroartemisinin plus a 640-mg/dose of PQ phosphate) from 0 to 672 h (A) and from 0 to 50 h (B).

TABLE 2.

Values of the main pharmacokinetic parameters of PQ and its two N-oxidation metabolites (M1 and M2) after a recommended two oral doses of QHS-PQ to nine healthy Chinese subjectsa

| Test drug | AUC0–24 (μmol · h · liter−1) | AUC24–672 (μmol · h · liter−1) | AUC0–672 (μmol · h · liter−1) | Cmax (nmol · liter−1) | Cday 7 (nmol · liter−1) | Tmax (h) | t1/2 (h) | CL/F (liters/h/kg) | AUCPQ-M/AUCPQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQ | 2.18 ± 2.27 | 23.49 ± 12.40 | 25.67 ± 14.47 | 424.5 ± 345.1 | 31.2 ± 13.7 | 26.5 (2.5–36.0) | 277.0 ± 58.6 | 1.55 ± 0.55 | NA |

| M1 | 0.76 ± 0.74 | 18.17 ± 6.07 | 18.93 ± 6.54 | 143.1 ± 77.2 | 30.7 ± 14.5 | 46.3 (28.0–96.0) | 231.7 ± 38.0 | NA | 0.80 ± 0.20 |

| M2 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.66 ± 0.29 | 0.70 ± 0.31 | 10.8 ± 5.9 | 1.2 ± 1.1 | 34.6 (26.5–61.0) | 70.9 ± 50.4 | NA | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

M1 is PQ N-oxide, and M2 is PQ N,N-dioxide. Artemisinin was given at 125 mg/dose, and PQ was given at 750 mg/dose. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation for all parameters except Tmax, which is given as the mean (range). AUC0–24, area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) from 0 h to 24 h; AUC24–672, AUC from 24 h to 672 h; AUC0–672, AUC from 0 h to 672 h; Cmax, peak plasma concentration; Cday 7, concentration at day 7 of treatment; Tmax, time to Cmax; t1/2, terminal elimination half-life; CL/F, oral body clearance; AUCPQ-M, AUC of the PQ metabolites; AUCPQ, AUC of PQ; NA, not acquired.

TABLE 3.

Values of the main pharmacokinetic parameters of PQ and its two N-oxidation metabolites (M1 and M2) after a recommended four oral doses of DHA-PQ phosphate to four healthy Chinese subjectsa

| Test drug | AUC0–6 (μmol · h · liter−1) | AUC6–24 (μmol · h · liter−1) | AUC24–30 (μmol · h · liter−1) | AUC30–672 (μmol · h · liter−1) | AUC0–672 (μmol · h · liter−1) | Cmax (nmol · liter−1) | Cday 7 (nmol · liter−1) | Tmax (h) | t1/2 (h) | CL/F (liters/h/kg) | AUCPQ-M/AUCPQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQ | 0.24 ± 0.04 | 3.14 ± 0.68 | 1.29 ± 0.45 | 42.86 ± 10.42 | 47.54 ± 11.25 | 902.1 ± 202.9 | 58.3 ± 16.3 | 34.5 (32.0–36.0) | 248.8 ± 25.6 | 0.86 ± 0.28 | NA |

| M1 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 1.02 ± 0.22 | 0.40 ± 0.15 | 25.54 ± 7.90 | 27.01 ± 8.27 | 270.1 ± 83.5 | 49.9 ± 24.1 | 35.5 (34.0–36.0) | 205.0 ± 24.4 | NA | 0.57 ± 0.13 |

| M2 | 0.001 ± 0.002 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 1.42 ± 0.55 | 1.52 ± 0.56 | 14.3 ± 3.8 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 35.5 (34.0–36.0) | 109.1 ± 33.2 | NA | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

M1 is PQ N-oxide, and M2 is PQ N,N-dioxide. Dihydroartemisinin was given at 80 mg/dose, and PQ phosphate was given at 640 mg/dose. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation for all parameters except Tmax, which is given as the mean (range). AUC0–6, area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) from 0 h to 6 h; AUC6–24, AUC from 6 h to 24 h; AUC24–30, AUC from 24 h to 30 h; AUC30–672, AUC from 30 h to 672 h; AUC0–672, AUC from 0 h to 672 h; Cmax, peak plasma concentration; Cday 7, concentration at day 7 of treatment; Tmax, time to Cmax; t1/2, terminal elimination half-life; CL/F, oral body clearance; AUCPQ-M, AUC of the PQ metabolites; AUCPQ, AUC of PQ; NA, not acquired.

PQ and M1 were the major forms in the blood circulation, and the exposure to M2 was much lower. The metabolic ratio of M1, calculated by the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) for M1 (AUCM1)/AUC for PQ (AUCPQ), was 0.8 (QHS-PQ) and 0.6 (DHA-PQ). The biotransformation of PQ to M2 was much lower, with a metabolic ratio of 0.03. The maximum concentrations of PQ and its metabolites were reached after the second (QHS-PQ; 26.5 h for PQ) or fourth (DHA-PQ; 34.5 h for PQ) dose in the majority of subjects. The concentration of PQ on day 7 dropped below 56.2 nM (30 ng/ml) in all subjects after administration of QHS-PQ, and the other regimen (DHA-PQ) showed a relatively higher PQ concentration on day 7 (42.9 to 80.0 nM). The metabolite M1 displayed a day 7 concentration equivalent to that of PQ; however, M2 was detected at a much lower concentration (<5.0 nM).

All subjects fulfilled the study without reporting any severe adverse events. The blood biochemical levels did not change significantly after the drug treatment.

DISCUSSION

Although extended parasite clearance times are indicative of artemisinin resistance, artemisinin drug-based combination therapy (ACT) remains important for the treatment of malaria. The long t1/2 of piperaquine (PQ) makes it a suitable partner to the short-acting artemisinin endoperoxides in a combination treatment. However, current dose regimens of PQ are empirically based rather than built on a sound understanding of its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. A 36% clinical failure rate was associated with patient PQ plasma levels in the terminal elimination phase falling below the PQ IC50s (17). In addition, the contribution of PQ metabolites remains unknown. Previous studies on the structure-activity relationship revealed that the 7-chloro group is essential for the antimalarial activity of the aminoquinoline compounds (14). PQ mainly underwent oxidation in vivo, and several phase I metabolites have been found in humans; these included two N-oxidation metabolites, a carboxylic acid, and two minor hydroxylated metabolites (12, 13). The carboxylic acid has been found to be bioactive. In the present study, the antimalarial activity of two major PQ metabolites (M1 and M2) was studied in vitro (in Plasmodium falciparum strains Pf3D7 and PfDd2) and in vivo (in the murine species Plasmodium yoelii). The pharmacokinetic profiles of PQ and its two metabolites (M1 and M2) were investigated in healthy subjects after oral doses of two widely used ACT regimens, i.e., dihydroartemisinin plus piperaquine phosphate and artemisinin plus piperaquine.

The in vitro susceptibilities of Plasmodium falciparum clones Pf3D7 (chloroquine sensitive) and PfDd2 (chloroquine resistant) to the model drug CQ were determined to be 14.9 nM (IC50) and 80.4 nM (IC50), respectively, which were in the range of the results presented in the literature (IC50, 5.7 to 40.0 nM for Pf3D7 and 62.0 to 135.4 nM for PfDd2) (18–20). PQ also showed antiplasmodial potency against two reference Plasmodium strains consistent with that presented in previous reports (∼10.0 nM for Pf3D7 and PfDd2) (21, 22). In freshly isolated strains of Plasmodium falciparum derived from malaria patients, the PQ IC50s ranged from 7.5 to 217.3 nM (23–25). Isolates with IC50s greater than 135.0 nM or 2.3-fold greater than the Pf3D7 IC50 have been considered to have reduced susceptibility to PQ (17). The progressively increasing PQ IC50s in northern Cambodia in recent years suggest the emergence of PQ resistance. In our study, two major PQ N-oxidation metabolites, M1 and M2, showed remarkable antiplasmodial activity against both Pf3D7 and PfDd2.

Differences may exist between in vitro activity and in vivo efficacy due to many factors, such as absorption and metabolism via the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes. PQ is metabolized by CYP3A4/CYP3A5 (26), which may also mediate the further biotransformation of M1 to M2. Even though metabolic biotransformation usually leads to inactivation of the parent drug, N-oxide has been reported to be bioactive in many cases (27, 28). In the present study, two PQ metabolites (M1 and M2) possessed potent in vivo suppression activity against the murine species Plasmodium yoelii, with ED50s of 1.3 and 2.9 mg/kg/day, respectively, following oral dosing. M1 showed efficacy similar to that of PQ in terms of the survival rate at each dose, and N,N-dioxidation of PQ (M2) led to a relatively lower efficacy. To simulate the common recommended dose regimen of ACTs (one dose a day for three consecutive days), three doses given at 24-h intervals were used to assess the antiplasmodial activity in P. yoelii-infected mice in our work. The PQ metabolites appeared to be well tolerated in mice at the doses of PQ administered, and the parasitemia of the mice accurately reflected the activity without being compromised by their possible toxicity.

The two PQ formulations used in our study achieved plasma concentrations in healthy subjects that were generally above the reported in vitro IC50s for PQ (∼10 nM), except at several time points at the absorption and elimination phases (after 4 or 14 days) at which samples were collected. The pharmacokinetic properties of PQ obtained in this study were similar to those presented in previous reports, e.g., body weight-adjusted clearance values of approximately 1.0 liter/h/kg, a long terminal t1/2 (∼11 days), and accumulation after repeated dosing. These studies are not entirely comparable due to the different formulations of PQ used and the effect of malaria or the concomitant fat intake. The oral clearance and apparent oral volume of distribution of PQ have been found to be lower in patients than in healthy subjects (29). PQ exposure was increased (∼3-fold) when administered with a high-fat/high-calorie meal (30). In addition, a shorter half-life (14 days) of PQ was found in children, and children had a CL/F (1.8 liters/h/kg) more rapid than that in adults (31), which probably reflects higher rates of hepatic metabolism and/or biliary excretion in children. The possible interaction between endoperoxides (QHS or DHA) and PQ in QHS-PQ or DHA-PQ is another issue that may lead to variations in PQ pharmacokinetic profiles.

After multiple oral doses, residual PQ exposure from previous doses cannot be accurately subtracted from that of the last dose because of its multiphasic distribution kinetics and long terminal elimination half-life. Therefore, the total amount of PQ base was used as the input dose in the noncompartmental analysis of PQ to compute pharmacokinetic estimates (CL/F). The peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and the time to the peak plasma concentration (Tmax) were taken directly from the observed data after all doses. The PQ exposure during the 24-hour (QHS-PQ) or 6-hour (DHA-PQ) dose intervals were determined following each dose, and evidence of accumulation was found for PQ, M1, and M2 after repeated administration. The terminal elimination half-life (t1/2) was estimated by log-linear regression of 4 to 5 observed concentrations in the terminal elimination phase. In the present study, a shorter half-life was found for PQ in healthy subjects. The terminal half-life of PQ in healthy adults estimated by noncompartmental methods has been reported to be ∼30 days (6, 9, 10). In these studies, sampling was discontinued after about 4 and 6 weeks. The estimated half-life may still underpredict the true terminal half-life since the ultimate disposition phase may not have been reached even after 28 or 42 days. A reliable estimate of the terminal half-life is of particular value in the case of PQ since it determines the duration of effects after treatment (and, as such, may influence the choice of duration of follow-up in clinical trials).

However, prolonged posttreatment exposure to PQ concentrations at subtherapeutic levels may place certain patients at a higher risk for parasites to develop drug resistance. The concentration determined at a single time point in the elimination phase of slowly eliminated antimalarials has previously been suggested to be a good predictor of therapeutic success. A plasma PQ concentration of >30 ng/ml (>56.2 nM) at day 7 is usually used as the threshold value for determining adequate PQ exposure (32). Indeed, it has been shown that this simplified measurement of exposure to PQ is particularly suitable for long-half-life drugs and better than the total area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC). In our study, the day 7 concentration was generally lower than this cutoff value in healthy subjects after they received the recommended oral doses of QHS-PQ or DHA-PQ for 2 days, which is probably predictive of treatment failure. It should also be noted that the result may be different in malaria patients due to slow hepatic clearance. In addition, the contribution of PQ metabolites M1 and M2 should also be considered. Equivalent plasma concentrations were detected for M1 and PQ at day 7, while a minor amount of M2 (<5.0 nM) was present.

Based on the ACT guidelines, a combination of antimalarial drugs must associate a drug with a short elimination half-life and a drug with a long elimination half-life. The high in vitro and in vivo antimalarial potency and lengthy half-life of the PQ metabolites (M1 and M2) suggest that they are important contributors to the efficacy of PQ. It has been recommended that partner drugs for ACT have a t1/2 of >4 days (at least two parasite life cycles). However, this is a debatable concept because the parasite is exposed to the long-half-life drug for a significant period of time to select parasite resistance. The metabolite M2 showed an elimination half-life (3 to 4 days) shorter than that of PQ (∼11 days) or M1 (∼9 days) in healthy subjects after oral doses of PQ. Of course, there remain more preclinical evaluations in order to validate the probable reversible biotransformation between PQ and its metabolites. What this study provides is the finding that PQ metabolites also have good potency against P. yoelii and P. falciparum malaria parasites. PQ and its two N-oxidation metabolites contribute to the overall antimalarial activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

Piperaquine phosphate and chloroquine (CQ) were purchased from the National Institutes for Food and Drug Control (purity > 99.0%; Beijing, China). Two metabolites of PQ (M1 and M2) were synthesized in our lab (purity > 99.0%; Shandong University, Jinan, China), and their structures were confirmed by high-resolution mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance. DHA-PQ tablets (Duo-Cotecxin) were purchased from Chongqing Holley Healthpro Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Chongqing, China), and QHS-PQ tablets (Artequick) were provided by Artepharm Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China). The other chemicals used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific.

Parasite strains.

The murine malaria parasite P. yoelii, chloroquine-sensitive strain Pf3D7, and chloroquine-resistant strain PfDd2 used in this study were obtained from the Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center (MR4) as a part of the BEI Resources Repository, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Animal handling.

Male ICR mice (weight, 20 to 25 g) and male Wistar rats (weight, 210 to 230 g) were supplied by the Lab Animal Center of Shandong University (grade II, certificate no. SYXK2013-0001). The experimental protocol was approved by the University Ethics Committee and conformed to the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (33). Lab animals were fasted for 12 h before drug administration and for a further 2 h after dosing. Water was freely available during the experiments.

In vivo 3-day suppression test.

Male ICR mice were treated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 1 × 107 red blood cells (RBCs) infected with P. yoelii. The vehicle control (0.03% acetic acid) or the tested drugs (dissolved in 0.03% acetic acid) were orally administered at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection. Efficacy was carried out using 3 to 5 different dose levels with nine mice at each level. Parasitemia was assessed by microscopic examination of Giemsa-stained blood smears on day 4 postinfection. The 50% or 90% growth-inhibitory doses (ED50 or ED90, respectively) of PQ or its metabolites (M1 and M2) were averages for three independent measurements (three mice in each dose group). Mice without the parasitemia were considered fully cured.

In vitro drug susceptibility.

The determination of the 50% or 90% growth-inhibitory concentration (IC50 or IC90, respectively) values of PQ or its metabolites against Pf3D7 or PfDd2 was performed using a previously reported protocol (19). In brief, test samples were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to give a stock solution, followed by serial dilution using RPMI 1640 complete medium to generate working stocks. A synchronous ring-stage parasite culture was prepared with a final 0.5% parasitemia and 2% hematocrit. The final content of DMSO in the incubation mixture was ≤0.1%, which did not affect the growth of the parasites. Chloroquine and 0.1% DMSO were used as the positive and negative controls, respectively. Plates were transferred to a gassed (90% N2, 5% O2, 5% CO2) airtight chamber and incubated at 37°C for 72 h. The antiplasmodial activity was determined by a fluorometric method using SYBR green I. Fluorescence was measured at 485/535 nm on a PerkinElmer Victor3 1420 multilabel plate reader (USA). IC50 and IC90 values were obtained from OriginPro (version 9.0) software and are the averages for two independent measurements each performed in duplicate.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of PQ and its metabolites in healthy subjects.

The experiment followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki for humans, and the experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University (Jinan, China) and the Institutional Review Board of Qilu Hospital (Shandong University, China). Each subject was in good health, as determined through the medical history, physical examination, and routine laboratory tests. Written consent was obtained from all volunteers after informing them about the objectives and possible risks involved in the study. The subjects were fasted overnight before drug administration and for a further 2 h after dosing. Water was freely available during the experiments.

Nine male subjects (age, 20 to 24 years; body weight, 61 to 82 kg; body mass index, 19 to 24 kg/m2) were treated with QHS-PQ tablets according to the manufacturer's recommendations (125 mg of QHS plus 750 mg of PQ each day for two consecutive days). Venous blood samples (1 ml) were taken from an indwelling intravenous catheter in the forearm at 0, 0.25, 0.75, 1.25, 1.75, 2.5, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 8.0, 12.0, 24.0, 24.25, 24.75, 25.25, 25.75, 26.5, 27.0, 28.0, 29.0, 30.0, 32.0, 36.0, 49.0, 61.0, 73.0, 96.0, 168.0, 336.0, and 672.0 h and collected in anticoagulant tubes before and after oral administration. Four subjects were treated with four oral doses of DHA-PQ tablets according to the manufacturer's recommendation (80 mg DHA plus 640 mg PQ phosphate for each dose at 0, 6, 24, and 30 h). Venous blood samples (1 ml) were taken from an indwelling intravenous catheter at 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0, 4.0, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, 8.0, 8.5, 9.0, 10.0, 12.0, 24.0, 24.5, 25.0, 25.5, 26.0, 26.5, 27.0, 28.0, 30.0, 30.5, 31.0, 31.5, 32.0, 32.5, 33.0, 34.0, 36.0, 48.0, 60.0, 72.0, 96.0, 168.0, 336.0, and 672.0 h. Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The plasma was stored at −80°C until analysis.

A liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method was applied for quantification of PQ and its metabolite on an API5500 Q-Trap triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Concord, Ontario, Canada) equipped with a turbo ion spray source. The sample preparation and chromatographic and mass spectrometric conditions have been described in a previous report (15), and the analytical method was fully validated. Representative chromatograms for quantification of PQ and its metabolites are shown in Fig. S3 in the supplemental material.

Statistical analysis.

Drug susceptibility was analyzed by a nonlinear regression of logarithmically transformed concentrations. The concentrations or doses that inhibited parasite growth by 50% (IC50s or ED50s) and 90% (IC90s or ED90s) were determined for PQ and its metabolites (M1 and M2). The peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and the time to the peak concentration (Tmax) were obtained from experimental observations. The other pharmacokinetic parameters were analyzed by use of a noncompartmental model and the program TOPFIT (version 2.0; Thomae GmbH, Germany). The area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) from 0 h to time t (AUC0–t) was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule to approximately the last point. Total oral body clearance (CL/F) was calculated as the total dose/AUC0–t. The terminal elimination half-life (t1/2) was estimated by log-linear regression in the terminal phase using an average of five observed concentrations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81373483 and no. 81773807).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00260-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. 2015. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria, 3rd ed WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohamed AO, Abdel Hamid MM, Mohamed OS, Elkando NS, Suliman A, Adam MA, Elnour FAA, Malik EM. 2017. Efficacies of DHA-PPQ and AS/SP in patients with uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria in an area of an unstable seasonal transmission in Sudan. Malar J 16:163. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1817-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nambozi M, Kabuya JB, Hachizovu S, Mwakazanga D, Mulenga J, Kasongo W, Buyze J, Mulenga M, Van Geertruyden JP, D'Alessandro U. 2017. Artemisinin-based combination therapy in pregnant women in Zambia: efficacy, safety and risk of recurrent malaria. Malar J 16:199. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1851-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imwong M, Suwannasin K, Kunasol C, Sutawong K, Mayxay M, Rekol H, Smithuis FM, Hlaing TM, Tun KM, van der Pluijm RW, Tripura R, Miotto O, Menard D, Dhorda M, Day NPJ, White NJ, Dondorp AM. 2017. The spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in the Greater Mekong subregion: a molecular epidemiology observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 17:491–497. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30048-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mbengue A, Bhattacharjee S, Pandharkar T, Liu H, Estiu G, Stahelin RV, Rizk SS, Njimoh DL, Ryan Y, Chotivanich K, Nguon C, Ghorbal M, Lopez-Rubio JJ, Pfrender M, Emrich S, Mohandas N, Dondorp AM, Wiest O, Haldar K. 2015. A molecular mechanism of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 520:683–687. doi: 10.1038/nature14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating GM. 2012. Dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine: a review of its use in the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Drugs 72:937–961. doi: 10.2165/11203910-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combrinck JM, Mabotha TE, Ncokazi KK, Ambele MA, Taylor D, Smith PJ, Hoppe HC, Egan TJ. 2013. Insights into the role of heme in the mechanism of action of antimalarials. ACS Chem Biol 8:133–137. doi: 10.1021/cb300454t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasay CJ, Rockett R, Sekuloski S, Griffin P, Marquart L, Peatey C, Wang CY, O'Rourke P, Elliott S, Baker M, Möhrle JJ, McCarthy JS. 2016. Piperaquine monotherapy of drug-susceptible Plasmodium falciparum infection results in rapid clearance of parasitemia but is followed by the appearance of gametocytemia. J Infect Dis 214:105–113. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leong FJ, Jain JP, Feng Y, Goswami B, Stein DS. 2018. A phase 1 evaluation of the pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic interaction of the anti-malarial agents KAF156 and piperaquine. Malar J 17:7. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-2162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarning J, Lindegårdh N, Annerberg A, Singtoroj T, Day NP, Ashton M, White NJ. 2005. Pitfalls in estimating piperaquine elimination. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:5127–5128. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.5127-5128.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarning J, Lindegårdh N, Sandberg S, Day NJ, White NJ, Ashton M. 2008. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of the antimalarial piperaquine after intravenous and oral single doses to the rat. J Pharm Sci 97:3400–3410. doi: 10.1002/jps.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarning J, Bergqvist Y, Day NP, Bergquist J, Arvidsson B, White NJ, Ashton M, Lindegårdh N. 2006. Characterization of human urinary metabolites of the antimalarial piperaquine. Drug Metab Dispos 34:2011–2019. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.011494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang A, Zang M, Liu H, Fan P, Xing J. 2016. Metabolite identification of the antimalarial piperaquine in vivo using liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry in combination with multiple data-mining tools in tandem. Biomed Chromatogr 30:1324–1330. doi: 10.1002/bmc.3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaur K, Jain M, Reddy RP, Jain R. 2010. Quinolines and structurally related heterocycles as antimalarials. Eur J Med Chem 45:3245–3264. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, Zang M, Yang A, Ji J, Xing J. 2017. Simultaneous determination of piperaquine and its N-oxidated metabolite in rat plasma using LC-MS/MS. Biomed Chromatogr 31:e3974. doi: 10.1002/bmc.3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aziz MY, Hoffmann KJ, Ashton M. 2017. LC-MS/MS quantitation of antimalarial drug piperaquine and metabolites in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1063:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaorattanakawee S, Saunders DL, Sea D, Chanarat N, Yingyuen K, Sundrakes S, Saingam P, Buathong N, Sriwichai S, Chann S, Se Y, Yom Y, Heng TK, Kong N, Kuntawunginn W, Tangthongchaiwiriya K, Jacob C, Takala-Harrison S, Plowe C, Lin JT, Chuor CM, Prom S, Tyner SD, Gosi P, Teja-Isavadharm P, Lon C, Lanteri CA. 2015. Ex vivo drug susceptibility testing and molecular profiling of clinical Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Cambodia from 2008 to 2013 suggest emerging piperaquine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4631–4643. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00366-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma N, Mohanakrishnan D, Sharma UK, Kumar R, Richa Sinha AK, Sahal D. 2014. Design, economical synthesis and antiplasmodial evaluation of vanillin derived allylated chalcones and their marked synergism with artemisinin against chloroquine resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum. Eur J Med Chem 79:350–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu M, Zhu J, Diao Y, Zhou H, Ren X, Sun D, Huang J, Han D, Zhao Z, Zhu L, Xu Y, Li H. 2013. Novel selective and potent inhibitors of malaria parasite dihydroorotate dehydrogenase: discovery and optimization of dihydrothiophenone derivatives. J Med Chem 56:7911–7924. doi: 10.1021/jm400938g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srivastava K, Agarwal P, Soni A, Puri SK. 2017. Correlation between in vitro and in vivo antimalarial activity of compounds using CQ-sensitive and CQ-resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum and CQ-resistant strain of P. yoelii. Parasitol Res 116:1849–1854. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desgrouas C, Dormoi J, Chapus C, Ollivier E, Parzy D, Taudon N. 2014. In vitro and in vivo combination of cepharanthine with anti-malarial drugs. Malar J 13:90. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Traore K, Lavoignat A, Bonnot G, Sow F, Bess GC, Chavant M, Gay F, Doumbo O, Picot S. 2015. Drying anti-malarial drugs in vitro tests to outsource SYBR green assays. Malar J 14:90. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0600-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dormoi J, Savini H, Amalvict R, Baret E, Pradines B. 2014. In vitro interaction of lumefantrine and piperaquine by atorvastatin against Plasmodium falciparum. Malar J 13:189. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pascual A, Madamet M, Briolant S, Gaillard T, Amalvict R, Benoit N, Travers D, Pradines B. 2015. Multinormal in vitro distribution of Plasmodium falciparum susceptibility to piperaquine and pyronaridine. Malar J 14:49. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0586-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasmussen SA, Ceja FG, Conrad MD, Tumwebaze PK, Byaruhanga O, Katairo T, Nsobya SL, Rosenthal PJ, Cooper RA. 2017. Changing antimalarial drug sensitivities in Uganda. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01516-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01516-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee TM, Huang L, Johnson MK, Lizak P, Kroetz D, Aweeka F, Parikh S. 2012. In vitro metabolism of piperaquine is primarily mediated by CYP3A4. Xenobiotic 42:1088–1095. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2012.693972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatzelmann A, Schudt C. 2001. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory potential of the novel PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297:267–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada S, Ito Y, Taki Y, Seki M, Nanri M, Yamashita F, Morishita K, Komoto I, Yoshida K. 2010. The N-oxide metabolite contributes to bladder selectivity resulting from oral propiverine: muscarinic receptor binding and pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab Dispos 38:1314–1321. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.033233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen DV, Nguyen QP, Nguyen ND, Le TT, Nguyen TD, Dinh DN, Nguyen TX, Bui D, Chavchich M, Edstein MD. 2009. Pharmacokinetics and ex vivo pharmacodynamic antimalarial activity of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Vietnam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:3534–3537. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01717-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reuter SE, Evans AM, Shakib S, Lungershausen Y, Francis B, Valentini G, Bacchieri A, Ubben D, Pace S. 2015. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of piperaquine and dihydroartemisinin. Clin Drug Invest 35:559–567. doi: 10.1007/s40261-015-0312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hung TY, Davis TM, Ilett KF, Karunajeewa H, Hewitt S, Denis MB, Lim C, Socheat D. 2004. Population pharmacokinetics of piperaquine in adults and children with uncomplicated falciparum or vivax malaria. Br J Clin Pharmacol 57:253–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leang R, Taylor WR, Bouth DM, Song L, Tarning J, Char MC, Kim S, Witkowski B, Duru V, Domergue A, Khim N, Ringwald P, Menard D. 2015. Evidence of Plasmodium falciparum malaria multidrug resistance to artemisinin and piperaquine in western Cambodia: dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine open-label multicenter clinical assessment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:4719–4726. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00835-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Institutes of Health. 1985. Principles of laboratory animal care. NIH publication no. 85-23, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.