This study aimed to characterize novel conjugative plasmids that encode transferable ciprofloxacin resistance in Salmonella. In this study, 157 nonduplicated Salmonella isolates were recovered from food products, of which 55 were found to be resistant to ciprofloxacin.

KEYWORDS: PMQR genes, Salmonella, ciprofloxacin resistance, conjugative plasmid

ABSTRACT

This study aimed to characterize novel conjugative plasmids that encode transferable ciprofloxacin resistance in Salmonella. In this study, 157 nonduplicated Salmonella isolates were recovered from food products, of which 55 were found to be resistant to ciprofloxacin. Interestingly, 37 of the 55 Cipr Salmonella isolates (67%) did not harbor any mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR). Six Salmonella isolates were shown to carry two novel types of conjugative plasmids that could transfer the ciprofloxacin resistance phenotype to Escherichia coli J53 (azithromycin resistant [Azir]). The first type of conjugative plasmid belonged to the ∼110-kb IncFIB-type conjugative plasmids carrying qnrB-bearing and aac(6′)-Ib-cr-bearing mobile elements. Transfer of the plasmid between E. coli and Salmonella could confer a ciprofloxacin MIC of 1 to 2 μg/ml. The second type of conjugative plasmid belonged to ∼240-kb IncH1/IncF plasmids carrying a single PMQR gene, qnrS. Importantly, this type of conjugative ciprofloxacin resistance plasmid could be detected in clinical Salmonella isolates. The dissemination of these conjugative plasmids that confer ciprofloxacin resistance poses serious challenges to public health and Salmonella infection control.

INTRODUCTION

Nontyphoidal Salmonella strains are among the principal bacterial causes of foodborne gastroenteritis worldwide (1). Antimicrobial agents are not usually required for treatment of salmonellosis but can be life-saving in cases of severe or systemic infections (2). Multidrug resistance (MDR) in Salmonella has been documented since 1980; a representative class of resistant organisms is the ACSSuT (ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamides, and tetracycline) resistance type of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104, which originated in the United Kingdom and spread rapidly to the United States and other parts of the world (3–6). Several lines of evidence have suggested that the emergence of multidrug-resistant nontyphoidal Salmonella strains has had a significant impact on the effectiveness of current strategies to control and manage diseases associated with foodborne infections (7). Resistance to ciprofloxacin (CIP) has increased dramatically in both clinical and food Salmonella isolates around the world in recent years, particularly in China and adjacent areas (8). Ciprofloxacin resistance is attributed mainly to double mutations in the gyrA gene and a single mutation in the parC gene in Salmonella (9, 10). Mutations in the gyrB and parE genes have rarely been detected in Salmonella strains and have not been confirmed to be associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella. Efflux pumps and the presence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) determinants have also been regarded as factors contributing to the development of low-level resistance to quinolones and fluoroquinolones.

At least three types of PMQR elements have been reported to date: (i) the Qnr types, pentapeptide repeat proteins that bind to DNA gyrase by mimicking double-stranded DNA, reduce the binding of gyrase to DNA, and protect topoisomerase IV from the quinolone; (ii) AAC(6′)-Ib-cr, a modified aminoglycoside acetyltransferase that modifies quinolones; and (iii) the efflux pumps QepA and OqxAB. PMQR elements used to be rare in Salmonella, but they have been increasingly detected, particularly in recent years (11–17). To date, many different types of PMQR have been reported in Salmonella, including the qnrA, qnrB, qnrD, and qnrS alleles, as well as a new PMQR gene, oqxAB (11, 12, 15, 17–24). oqxAB was found in Escherichia coli on plasmid pOLA52 in 2003 and was then detected in Salmonella isolates recovered from various sources (8, 25, 26). The oqxAB and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes often coexist in the same strain and may be associated with the increase in the incidence of ciprofloxacin resistance in clinical Salmonella strains in recent years (27). However, these PMQR genes retained their role in mediating quinolone resistance or reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin) in Salmonella. The presence of PMQR together with target mutations might confer resistance to fluoroquinolones (27). Recent studies have shown that increasing numbers of ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella isolates did not carry any mutation in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) of the target genes, although they carried a combination of various PMQR genes (25). However, these PMQR genes were normally located on the chromosome or nonconjugative plasmids in Salmonella (25). In the present study, we report two types of conjugative ciprofloxacin-resistant plasmids that harbor a variety of PMQR genes in Salmonella. Transmission of these plasmids in Salmonella might be responsible for the rapid increase in the frequency of ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella strains in recent years and may impair the effectiveness of ciprofloxacin in the treatment of Salmonella infections.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Prevalence of Salmonella in food.

A total of 157 Salmonella isolates were collected from retail meat products (113 pork and 27 chicken samples) purchased from supermarkets and wet markets in Shenzhen, China, during the period from January 2014 to January 2015. The isolation rate was found to differ throughout the sampling interval, ranging from 72% in the summer to 12% in the winter months. The prevalences of Salmonella in pork and chicken were 48% and 45%, respectively. Fourteen different serotypes were identified, of which Salmonella enterica serotype Derby, Salmonella enterica serotype London, and Salmonella enterica serotype Rissen were the most common, accounting for 33%, 13%, and 13%, respectively, of the 157 Salmonella strains tested. S. Typhimurium and Salmonella enterica serotype 4,12:i:− accounted for about 10% and 6% of the test strains, respectively. Further subtyping by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) revealed a total of 80 different PFGE patterns. A total of 33 PFGE patterns were observed among the 52 S. Derby isolates, and 12 and 6 PFGE patterns were observed among 20 isolates each of S. Rissen and S. London, respectively. The Salmonella isolation rate was higher than those in reports from our previous study and other groups, while the distribution of serotypes was quite consistent (24, 28).

Ciprofloxacin resistance mediated by target mutations and PMQR.

Fifty-five of the 157 Salmonella isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin (Cipr), among which S. Derby, S. 4,12:i:−, S. Typhimurium, and S. London were the dominant serotypes. Target mutations were detected in 19 of the 55 Cipr isolates, with different types of amino acid substitutions in GyrA, such as D87G, D87N, S83F, S83Y, and S83F D87N. No target mutation was detected in the gyrB and parC genes. In addition to target mutations, various PMQR genes, such as oqxAB and aac(6′)-Ib-cr, were detected in some of the isolates. Target mutations seemed to be serotype dependent, since they were commonly detected in S. 4,12:i:−, S. Typhimurium, Salmonella enterica serotype Infantis, Salmonella enterica serotype Albany, and Salmonella enterica serotype Indiana, but not in other serotypes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In agreement with other reports, the combination of a single gyrA mutation and a PMQR gene could confer resistance to fluoroquinolones, which might speed up the development of ciprofloxacin resistance in Salmonella (27).

Ciprofloxacin resistance mediated solely by PMQR genes, not by target mutations.

Interestingly, 37 of the 55 (67%) Cipr Salmonella isolates did not harbor any mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) of the target genes (Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These Salmonella strains were most often found to belong to S. Derby, S. London, Salmonella enterica serotype Meleagridis, Salmonella enterica serotype Thompson, and Salmonella enterica serotype Agona. Multiple PMQR genes, in a variety of combinations, were detected in these isolates. Various combinations of qnr genes were detected in these strains, including qnrS–oqxAB–aac(6′)-Ib-cr (commonly seen in S. Derby), aac(6′)-Ib-cr–oqxAB–qnrS8–qnrD, qnrS–oqxAB, and qnrS only in various serotypes of Salmonella (Fig. S1).

Mechanisms of ciprofloxacin resistance in Salmonella isolates.

Conjugation experiments were performed on the 37 Cipr isolates that did not have target mutations, and it was shown that 14 of the 37 Salmonella isolates could successfully transfer their ciprofloxacin resistance phenotype to the recipient strain E. coli J53 (azithromycin resistant [Azir]). S1 nuclease-PFGE was performed on these 14 strains and their transconjugants. Eight of the 14 Salmonella isolates carried multiple plasmids, none of which was similar in size to the plasmids carried by their transconjugants (data not shown). These Salmonella strains and their transconjugants were not included in this study. Each of the other six Salmonella isolates carried a single plasmid, which could be successfully transferred to E. coli J53 (Azir), suggesting that these plasmids were ciprofloxacin resistance-encoding conjugative plasmids. All transconjugants carried conjugative plasmids the same size as those of the parental Salmonella strains (Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The MICs of various antibiotics were determined for the donor strains and E. coli transconjugants. The results showed that the ciprofloxacin MICs were 2 to 4 μg/ml for five parental Salmonella strains and 1 to 2 μg/ml for their transconjugants; in one case, the CIP MIC was 1 μg/ml for the strain and 0.5 μg/ml for its transconjugant (Table 1). In addition to the ciprofloxacin resistance phenotype, the conjugative plasmids also carried resistance to ampicillin, tetracycline, and streptomycin (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Genetic and phenotypic characteristics of ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella strains and the corresponding transconjugants

| Strain IDa | Species, parental strain, or serotype | PMQR genes | Approx plasmid size (kb) | MICb |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMK | CTX | LEV | CIP | CIP + Ihi | KAN | OLA | STR | CRO | TET | CHL | NAL | AMP | MRP | SXT | ||||

| ATCC 25922 | E. coli | 4 | 0.06 | 0.015 | 0.0075 | 0.0075 | 2 | 16 | 8 | 0.03 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 0.015 | 1 | ||

| J53 (Azir) | E. coli | ≤0.5 | ≤0.015 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.0075 | ≤0.5 | 4 | 2 | ≤0.015 | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ≤0.125 | 4 | ||

| Sa63 | S. London | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 113 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 16 | >128 | 0.06 | >32 | >64 | 16 | >64 | 0.06 | >32 |

| TC-Sa63 | E. coli J53 | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 113 | 2 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 16 | 16 | 128 | 0.03 | 32 | 2 | 8 | >64 | 0.12 | 16 |

| Sa81 | Salmonella enterica serotype O3,O10 | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 113 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 32 | >128 | 0.06 | >32 | >64 | 16 | >64 | 0.12 | 32 |

| TC-Sa81 | E. coli J53 | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 113 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 8 | 128 | 0.03 | >32 | 2 | 8 | >64 | 0.12 | 16 |

| Sa100 | S. Thompson | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 113 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 32 | 64 | >128 | 0.25 | >32 | >64 | 32 | >64 | 0.12 | >32 |

| TC-Sa100 | E. coli J53 | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 113 | 2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.5 | 16 | 16 | 128 | 0.06 | 32 | 2 | 8 | >64 | 0.12 | 32 |

| Sa76 | S. London | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 104 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 16 | >128 | 0.06 | >32 | >64 | 16 | >64 | 0.06 | 32 |

| TC-Sa76 | E. coli J53 | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 104 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 16 | 64 | 0.06 | >32 | 2 | 8 | >64 | 0.12 | 16 |

| Sa117 | S. London | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 104 | 4 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 32 | >128 | 0.06 | >32 | >64 | 16 | >64 | 0.12 | 32 |

| TC-Sa117 | E. coli J53 | qnrB6–aac(6′)-Ib-cr | 104 | 1 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 | 8 | 128 | ≤0.015 | 16 | 2 | 8 | >64 | 0.12 | 16 |

| Sa4 | S. Typhimurium | qnrS1 | 237 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 2 | 32 | 16 | 0.06 | 1 | >64 | 8 | >64 | 0.12 | >32 |

| TC-Sa4 | E. coli J53 | qnrS1 | 237 | ≤0.5 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | ≤0.5 | 8 | 8 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 2 | 8 | >64 | 0.06 | 16 |

| Sa48 | S. London | 1 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.015 | 0.0075 | 8 | 16 | >128 | 0.06 | >32 | 64 | 8 | 16 | 0.06 | 8 | ||

ID, identification; TC, transconjugant.

AMK, amikacin; CTX, cefotaxime; LEV, levofloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; Ihi, Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide (80 μg/ml); KAN, kanamycin; OLA, olaquindox; STR, streptomycin; CRO, ceftriaxone; TET, tetracycline; CHL, chloramphenicol; NAL, nalidixic acid; AMP, ampicillin; MRP, meropenem; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

To ensure that the resistance to ciprofloxacin was not due to the selection of a target mutation in the E. coli transconjugants, conjugation was performed by selecting transconjugants on an eosin methylene blue (EMB) plate containing ampicillin and sodium azide. Transconjugants were obtained for the six Salmonella isolates, and they displayed MICs to various antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin, very similar to those for transconjugants selected by ciprofloxacin and sodium azide, suggesting that the conjugative plasmid indeed encoded a ciprofloxacin resistance phenotype (data not shown). Although the CIP MIC for transconjugants was ∼2-fold lower than that for the parental strains, if the conjugative plasmids recovered from E. coli J53 (Azir) transconjugants were transferred back to a ciprofloxacin-susceptible (Cips) Salmonella strain, namely, S. Typhimurium Sa48 (one of the 157 Salmonella isolates from this study), a CIP MIC level equal to that of the parental Salmonella strain carrying the test plasmid was restored, suggesting that these conjugative plasmids could mediate slightly higher MICs in Salmonella than in E. coli (data not shown). The CIP MIC was further determined in the presence of an efflux pump inhibitor, Phe-Arg-β-naphthylamide, which caused a 1- to 4-fold reduction in the CIP MIC, suggesting that efflux pumps were not the major contributors to the ciprofloxacin resistance in these strains (Table 1). All these conjugative plasmids showed similar sizes (∼110 kb) except for strain Sa4, which carried a conjugative plasmid of ∼240 kb.

Transmission of ciprofloxacin resistance by conjugative plasmids.

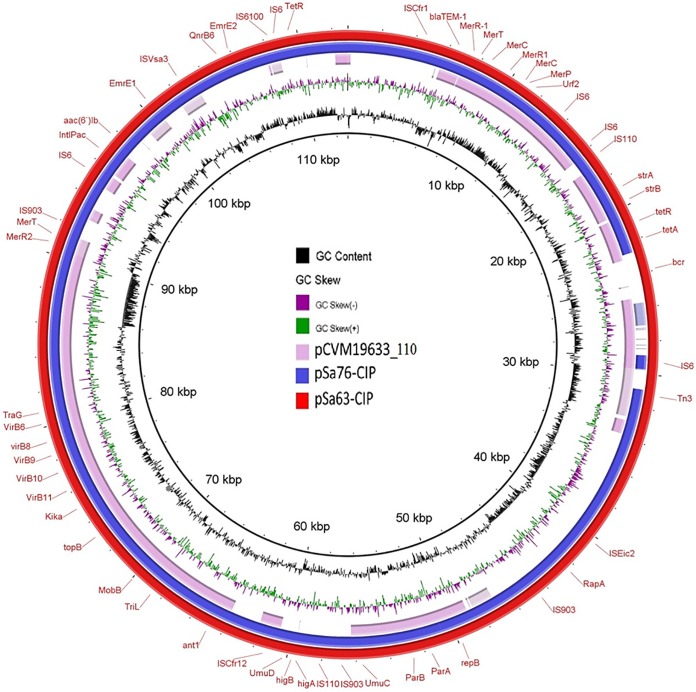

To gain further understanding of the genetic features of these mobile resistance elements, complete sequences of these plasmids were obtained using the Illumina and PacBio sequencing platforms. Strains Sa63, Sa81, and Sa100 were found to harbor IncFIB(K) plasmids, namely, pSa63-CIP (GenBank accession number MG874043), pSa81-CIP, and pSa100-CIP, respectively, all with a size of ∼113 kb. Strains Sa76 and Sa117 carried IncFIB(K) plasmids pSa76-CIP and pSa117-CIP, respectively, with a size of ∼104 kb (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). All five IncFIB(K) conjugative plasmids contained the PMQR genes qnrB6–aac(6)-Ib-cr and exhibited high-level homology to each other (Fig. 1). BLAST analysis showed that this type of plasmid has not been reported previously. The only plasmid in GenBank that exhibited homology was plasmid pCVM19633_110, which was isolated from a Salmonella enterica serotype Schwarzengrund strain, CVM19633. Plasmid pSa63-CIP exhibited 99% similarity with pCVM19633-110 but only 64% coverage, suggesting that this type of conjugative plasmid was novel in structure. However, the detection of a plasmid with a similar backbone in the United States may suggest the possible transmission of this type of plasmid in other parts of the world. The ∼104-kb plasmid from Sa76, pSa76-CIP (GenBank accession number MG874044), and the ∼113-kb plasmids shared almost identical structure with the ∼104-kb plasmid, which lacked a fragment of the backbone sequence relative to the ∼113-kb plasmid. Interestingly, although strains Sa31 and Sa148 had XbaI PFGE profiles identical to those of Sa76 and Sa103, and strain Sa99 had an XbaI profile identical to that of Sa100 (Fig. S1), they carried different types of plasmids that differed from those carried by Sa76 and Sa100 and were not conjugative, suggesting that the intake of different mobile genetic elements by the same clone of Salmonella happens commonly in nature (data not shown).

FIG 1.

Alignment of ciprofloxacin-resistant conjugative IncFIB(K)-type plasmids from Salmonella using the BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG). Plasmids pSa76-CIP (104,666 bp), pSa63-CIP (112,943 bp), and pCVM19633_110 (accession number CP001125) in the NCBI database were analyzed. The sequence of pSa63-CIP was used as a reference (red circle), and key genetic loci are labeled. Plasmid sequences were generated through the combination of Illumina and PacBio sequencing data. The aac(6′)-Ib-cr gene is annotated as aac(6′)-Ib.

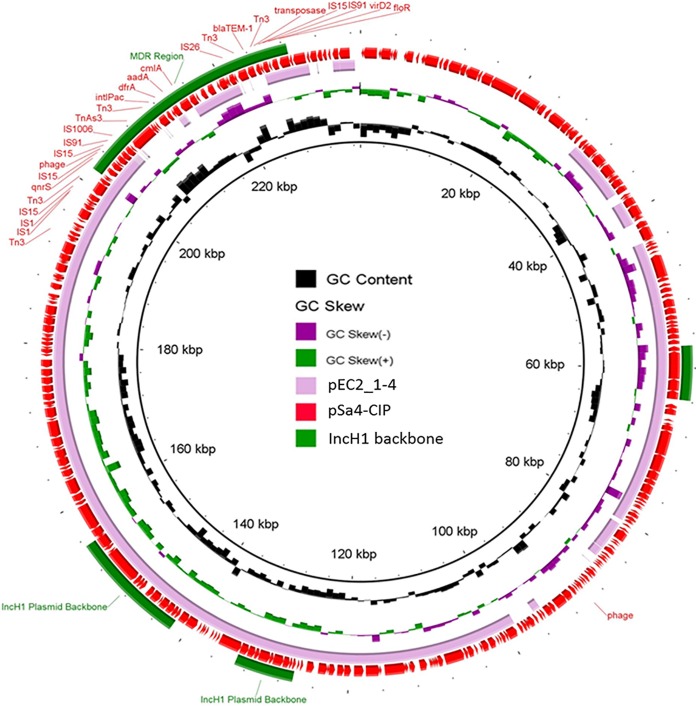

In addition to the IncFIB(K)-type conjugative plasmids, strain Sa4 was found to carry an IncH1/IncF-type plasmid, pSa4-CIP (GenBank accession number MG874042), which had a size of 237,130 bp and contained only one PMQR gene, qnrS1. Transfer of this plasmid to E. coli J53 (Azir) by conjugation resulted in a 2-fold decrease in the CIP MIC for E. coli (0.5 μg/ml). However, transfer of this plasmid back to the Cips S. Typhimurium strain Sa48 again resulted in a CIP MIC of 1 μg/ml. The pSa4-CIP plasmid had a GC content of 47.1% and 307 coding sequences (CDSs) and exhibited 73% similarity and 73% coverage with plasmid pEC2_1-4, harbored by the E. coli strain EC2_1 (NCBI database accession number CP016183.1). pSa4-CIP contained an MDR region, which comprised several antibiotic resistance genes (qnrS, dfrA, aadA, cmlA, blaTEM, and floR) and numerous insertion sequence (IS) elements (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Alignment of pSa4-CIP with its best BLAST hit, pEC2_1-4 (NCBI database accession number CP016183), using the BLAST Ring Image Generator (BRIG). Representative genes and genetic regions of pSa4-CIP (237,130 bp) are labeled. MDR, multidrug resistance. Plasmid sequences were generated through the combination of Illumina and PacBio sequencing data.

Prevalence of conjugative ciprofloxacin resistance-encoding plasmids in clinical Salmonella strains.

PCR assays targeting IncFIB(K) were used to test for the presence of the Cipr conjugative plasmids in clinical Salmonella isolates. IncFIB(K)-type plasmids were detected in 6 (4%) of the 159 Cipr Salmonella isolates collected in 2015 but not in 1,826 clinical Salmonella isolates collected during the period from 2004 to 2014. Among the six Salmonella isolates carrying the IncFIB(K) plasmid, five were S. London and one was S. Derby. A particular concern is the detection of these conjugative plasmids in clinical Salmonella isolates, which may have contributed to the dramatic increase of rate of Cipr in Salmonella in these years. Global transmission of these plasmids in clinical Salmonella strains would be expected owing to the globalization of food, which may facilitate the transmission of Salmonella strains and resistant elements globally. The transmission of conjugative plasmids encoding the ciprofloxacin resistance phenotype in different bacteria is expected to impair the effectiveness of fluoroquinolone antibiotics in treating bacterial infections.

In conclusion, this study discovered two types of conjugative plasmids encoding resistance to ciprofloxacin in Salmonella. The carriage of conjugative ciprofloxacin resistance plasmids in Salmonella may have serious impacts on Salmonella infection control efforts globally, since fluoroquinolones are the first choice of treatment for Salmonella infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Salmonella isolates.

Salmonella isolates were recovered from different foods as described previously (25) with slight modifications. Salmonella strains were confirmed by detection of the Salmonella-specific gene invA and 16S rRNA sequencing. All Salmonella isolates were subjected to serotyping according to the Kauffmann-White scheme by use of a commercial antiserum (Difco, Detroit, MI). Only one isolate from each sample was used for further characterization, except when isolates of different serotypes were detected in the same sample. Clinical Salmonella isolates were obtained from patients in hospitals in China.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility to 14 antimicrobials (Table 1) was determined using the agar dilution method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (29). Escherichia coli strain ATCC 25922 was used for quality control. Isolates that exhibited resistance to at least three different classes of agents were classified as multidrug resistant. The MIC breakpoints were ≥1 μg/ml for ciprofloxacin resistance and ≥4 μg/ml for ceftriaxone resistance. Breakpoints for both streptomycin and olaquindox were set at ≥32 μg/ml. MIC experiments were repeated at least three times for each strain.

Prevalence of target gene mutations and PMQR genes.

All Salmonella strains were screened for PMQR genes and for target mutations in the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes by PCR using primers described previously (15). The PCR products were purified and were subjected to Sanger sequencing to confirm their genetic identity or the types of mutational changes that they harbored.

Conjugation experiments.

The transmission of PMQR or blaCTX-M genes was assessed by performing the conjugation experiment using the filter-mating method as described previously (8). Transconjugants were selected on EMB agar containing either ampicillin (16 μg/ml) and sodium azide (100 μg/ml) or ciprofloxacin (0.5 μg/ml) and sodium azide (100 μg/ml). Both these transconjugants and their parental strains were tested for antimicrobial susceptibility. For testing of the host specificity of specific plasmids, transconjugants were used as donor strains in conjugation experiments to assess whether the conjugative plasmids could be transferred back from the E. coli J53 (Azir) strain to Salmonella.

Epidemiological typing.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (CHEF Mapper system; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to assess the genetic relatedness between the test isolates and the corresponding transconjugants as described previously (30). Transconjugants harboring plasmids were analyzed by S1 nuclease-PFGE.

Plasmid sequencing and bioinformatics analyses.

Plasmids were extracted from transconjugant strains using the Qiagen (Valencia, CA) Plasmid Midi kit. Plasmids were sequenced on an Illumina platform and a PacBio RSII single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing platform. Illumina paired-end libraries were constructed with the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs) and were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 platform. SMRT sequencing was performed at the Wuhan Institute of Biotechnology, Wuhan, China. De novo assemblies of PacBio RSII reads and Illumina reads were performed by the hierarchical genome assembly process (HGAP; Pacific Biosciences) and the CLC Genomics Workbench (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark), respectively. Long assembled contigs obtained from PacBio reads were used to align and join the contigs obtained from the Illumina assembly results. The completed plasmid sequences were first confirmed by PCR and then annotated with the RAST tool (31) and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP). Each plasmid was sequenced using both the Illumina and PacBio platforms, and only high-quality data were used for further analysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grant Council Collaborative Research Fund (grants C7038-15G and C5026-16G) and the Health and Medical Research Fund (HMRF) of the Food and Health Bureau, Government of the Hong Kong SAR (grant 14130402, to S.C.).

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00575-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gomez TM, Motarjemi Y, Miyagawa S, Kaferstein FK, Stohr K. 1997. Foodborne salmonellosis. World Health Stat Q 50:81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hohmann EL. 2001. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Clin Infect Dis 32:263–269. doi: 10.1086/318457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. 1997. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella serotype Typhimurium—United States, 1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 46:308–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markogiannakis A, Tassios PT, Lambiri M, Ward LR, Kourea-Kremastinou J, Legakis NJ, Vatopoulos AC. 2000. Multiple clones within multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium phage type DT104. The Greek Nontyphoidal Salmonella Study Group. J Clin Microbiol 38:1269–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glynn MK, Bopp C, Dewitt W, Dabney P, Mokhtar M, Angulo FJ. 1998. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium DT104 infections in the United States. N Engl J Med 338:1333–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leekitcharoenphon P, Hendriksen RS, Le Hello S, Weill FX, Baggesen DL, Jun SR, Ussery DW, Lund O, Crook DW, Wilson DJ, Aarestrup FM. 2016. Global genomic epidemiology of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:2516–2526. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03821-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mølbak K. 2005. Human health consequences of antimicrobial drug-resistant Salmonella and other foodborne pathogens. Clin Infect Dis 41:1613–1620. doi: 10.1086/497599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong MH, Yan M, Chan EW, Biao K, Chen S. 2014. Emergence of clinical Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolates with concurrent resistance to ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, and azithromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3752–3756. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02770-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooper DC. 2001. Emerging mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Emerg Infect Dis 7:337–341. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S, Zhao S, White DG, Schroeder CM, Lu R, Yang H, McDermott PF, Ayers S, Meng J. 2004. Characterization of multiple-antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella serovars isolated from retail meats. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:1–7. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.1-7.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Z, Meng X, Wang Y, Xia X, Wang X, Xi M, Meng J, Shi X, Wang D, Yang B. 2014. Presence of qnr, aac(6′)-Ib, qepA, oqxAB, and mutations in gyrase and topoisomerase in nalidixic acid-resistant Salmonella isolates recovered from retail chicken carcasses. Foodborne Pathog Dis 11:698–705. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Yang B, Wu Y, Zhang Z, Meng X, Xi M, Wang X, Xia X, Shi X, Wang D, Meng J. 2015. Molecular characterization of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis on retail raw poultry in six provinces and two national cities in China. Food Microbiol 46:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geetha VK, Yugendran T, Srinivasan R, Harish BN. 2014. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in typhoidal salmonellae: a preliminary report from South India. Indian J Med Microbiol 32:31–34. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.124292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kao CY, Chen CA, Liu YF, Wu HM, Chiou CS, Yan JJ, Wu JJ. 2015. Molecular characterization of antimicrobial susceptibility of Salmonella isolates: first identification of a plasmid carrying qnrD or oqxAB in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wasyl D, Hoszowski A, Zajac M. 2014. Prevalence and characterisation of quinolone resistance mechanisms in Salmonella spp. Vet Microbiol 171:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones-Dias D, Manageiro V, Francisco AP, Martins AP, Domingues G, Louro D, Ferreira E, Canica M. 2013. Assessing the molecular basis of transferable quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. from food-producing animals and food products. Vet Microbiol 167:523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veldman K, Cavaco LM, Mevius D, Battisti A, Franco A, Botteldoorn N, Bruneau M, Perrin-Guyomard A, Cerny T, De Frutos Escobar C, Guerra B, Schroeter A, Gutierrez M, Hopkins K, Myllyniemi AL, Sunde M, Wasyl D, Aarestrup FM. 2011. International collaborative study on the occurrence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli isolated from animals, humans, food and the environment in 13 European countries. J Antimicrob Chemother 66:1278–1286. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szmolka A, Fortini D, Villa L, Carattoli A, Anjum MF, Nagy B. 2011. First report on IncN plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance gene qnrS1 in porcine Escherichia coli in Europe. Microb Drug Resist 17:567–573. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2011.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunell M, Webber MA, Kotilainen P, Lilly AJ, Caddick JM, Jalava J, Huovinen P, Siitonen A, Hakanen AJ, Piddock LJ. 2009. Mechanisms of resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica strains exhibiting a nonclassical quinolone resistance phenotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:3832–3836. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00121-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrari R, Galiana A, Cremades R, Rodriguez JC, Magnani M, Tognim MC, Oliveira TC, Royo G. 2011. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance by genes qnrA1 and qnrB19 in Salmonella strains isolated in Brazil. J Infect Dev Ctries 5:496–498. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ceyssens PJ, Mattheus W, Vanhoof R, Bertrand S. 2015. Trends in serotype distribution and antimicrobial susceptibility in Salmonella enterica isolates from humans in Belgium, 2009 to 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:544–552. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04203-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abgottspon H, Zurfluh K, Nüesch-Inderbinen M, Hächler H, Stephan R. 2014. Quinolone resistance mechanisms in Salmonella enterica serovars Hadar, Kentucky, Virchow, Schwarzengrund, and 4,5,12:i:−, isolated from humans in Switzerland, and identification of a novel qnrD variant, qnrD2, in S. Hadar. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3560–3563. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02404-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nüesch-Inderbinen M, Abgottspon H, Sagesser G, Cernela N, Stephan R. 2015. Antimicrobial susceptibility of travel-related Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi isolates detected in Switzerland (2002–2013) and molecular characterization of quinolone resistant isolates. BMC Infect Dis 15:212. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0948-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang T, Zeng Z, Rao L, Chen X, He D, Lv L, Wang J, Zeng L, Feng M, Liu JH. 2014. The association between occurrence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance and ciprofloxacin resistance in Escherichia coli isolates of different origins. Vet Microbiol 170:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin D, Chen K, Wai-Chi Chan E, Chen S. 2015. Increasing prevalence of ciprofloxacin-resistant food-borne Salmonella strains harboring multiple PMQR elements but not target gene mutations. Sci Rep 5:14754. doi: 10.1038/srep14754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sørensen AH, Hansen LH, Johannesen E, Sorensen SJ. 2003. Conjugative plasmid conferring resistance to olaquindox. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:798–799. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.798-799.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong MH, Chan EW, Liu LZ, Chen S. 2014. PMQR genes oqxAB and aac(6′)Ib-cr accelerate the development of fluoroquinolone resistance in Salmonella typhimurium. Front Microbiol 5:521. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin D, Yan M, Lin S, Chen S. 2014. Increasing prevalence of hydrogen sulfide negative Salmonella in retail meats. Food Microbiol 43:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CLSI. 2016. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-sixth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S26. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribot EM, Fair MA, Gautom R, Cameron DN, Hunter SB, Swaminathan B, Barrett TJ. 2006. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog Dis 3:59–67. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2006.3.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, Disz T, Edwards RA, Gerdes S, Parrello B, Shukla M, Vonstein V, Wattam AR, Xia F, Stevens R. 2014. The SEED and the Rapid Annotation of microbial genomes using Subsystems Technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res 42:D206–D214. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.