ABSTRACT

Two paenipeptin analogues at 4 μg/ml potentiated clarithromycin and rifampin against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. The combined treatment significantly increased their antibacterial efficacy in a microbiological medium and in human serum in vitro at therapeutically relevant concentrations. Moreover, these two paenipeptin analogues showed low cytotoxicity against a human kidney cell line. Therefore, combination therapy with paenipeptins may be an option for the treatment of antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

KEYWORDS: clarithromycin, combination therapy, lipopeptide, paenipeptin, rifampin

TEXT

Gram-negative bacteria are naturally insensitive to many hydrophobic antibiotics because of the permeability barriers of the outer membranes (1). The emergence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, such as carbapenem-resistant pathogens, further limits the therapeutic options to treat bacterial infections (2). Antibiotic potentiators are molecules that usually lack direct antibacterial activity but which promote the activity of other antibiotics by damaging the integrity of the outer membrane, allowing the uptake of active antibiotics to take action intracellularly (3).

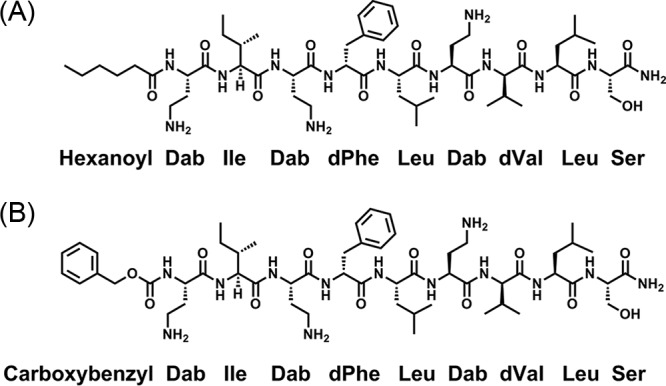

Paenipeptin (C8-Pat) is a novel synthetic lipopeptide antimicrobial agent that consists of an N-terminal C8 fatty acyl chain and a 9-residue linear peptide with three positively charged amino acids (4). Through structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies, we previously identified two new analogues (1 and 15), which are nonhemolytic at 128 μg/ml. Paenipeptin analogue 1 possesses a shorter lipid chain (C6) in comparison with paenipeptin C8-Pat, whereas analogue 15 substitutes the lipid chain with a hydrophobic carboxybenzyl group (Fig. 1). These two analogues potentiated rifampin against two reference strains, Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883. The cationic nature of paenipeptin analogues may disrupt the outer membrane of Gram-negative pathogens, which promotes the entry of hydrophobic antibiotics to attack the intracellular drug targets (5). In this study, we aimed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of paenipeptin analogues (1 and 15) and determined the potential potentiation with clarithromycin or rifampin against 10 carbapenem-resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae from the FDA-CDC Antimicrobial Resistance Isolate Bank.

FIG 1.

Chemical structure of paenipeptin analogues 1 and 15. (A) Analogue 1; (B) analogue 15. Dab, 2,4-diaminobutyric acid.

Paenipeptin analogues (>95% purity) were chemically synthesized by a commercial peptide service company (Genscript Inc., Piscataway, NJ). The chemical structure was verified using high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (5). Cytotoxicity of paenipeptin analogues was determined against a human kidney cell line (HEK 293) using MTT [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] assays (6). Cell viability was measured at 24 h, following the addition of lipopeptides at concentrations between 30 to 105 μg/ml. The viability of human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293) decreased with the increase of paenipeptin concentration. The viability of HEK 293 cells in the presence of paenipeptin analogue 1 and 15 at 105 μg/ml was 61% and 67%, respectively (Table 1). The relatively low cytotoxicity of paenipeptin analogues 1 and 15 was correlated with their low hemolytic activity against red blood cells (5). Low levels of cytotoxicity permit the further development of these two new paenipeptin analogues.

TABLE 1.

Viability of human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293) after treatment with paenipeptin analogues 1 and 15 for 24 h

| Analogue | Viability (%, mean ± SD) at: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 μg/ml | 45 μg/ml | 60 μg/ml | 75 μg/ml | 90 μg/ml | 105 μg/ml | |

| 1 | 85.23 ± 10.15 | 78.41 ± 11.15 | 78.43 ± 13.49 | 73.09 ± 11.35 | 69.03 ± 8.14 | 61.01 ± 6.38 |

| 15 | 91.39 ± 4.09 | 84.32 ± 8.12 | 82.04 ± 4.54 | 73.34 ± 5.37 | 67.13 ± 10.03 | 67.47 ± 9.66 |

The MICs of clarithromycin (a protein synthesis inhibitor), rifampin (an RNA synthesis inhibitor), polymyxin B nonapeptide, paenipeptin analogues, or their combinations were determined against 10 carbapenem-resistant strains using a microdilution method (5). Paenipeptin analogue 1 or 15 alone showed inhibitory activity against certain A. baumannii isolates, such as AR 0037, AR 0052, AR 0063, and AR 0070, which were also susceptible to rifampin (Table 2). The increased susceptibility of these isolates could be strain dependent, with a higher rate of susceptibility in A. baumannii strains; none of the five tested K. pneumoniae strains was susceptible to paenipeptin or rifampin. Paenipeptins 1 and 15 showed similar MICs in the presence of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), which was used in the tissue culture experiments for cytotoxicity assays. Polymyxin B nonapeptide, which is known as an antibiotic potentiator (1), was not effective against all 10 tested strains (MIC, >32 μg/ml) when used alone (Table 2). As showed in Table 3, the combination of polymyxin B nonapeptide with clarithromycin or rifampin showed a moderate potentiation effect compared to paenipeptin analogues. In contrast, paenipeptin analogues dramatically increased the antibacterial activity of clarithromycin and rifampin. For example, paenipeptin analogues 1 and 15 at 4 μg/ml decreased the MIC of clarithromycin against A. baumannii FDA-CDC AR 0037 from 16 μg/ml to 0.0313 and 0.0019 μg/ml, respectively, which corresponded to a 512- to 8,192-fold increase in its antibiotic activity (Table 3). These results were consistent with our previous findings, where paenipeptin analogues increased the efficacy of antibiotics against antibiotic-susceptible reference strains (5).

TABLE 2.

MIC of clarithromycin, rifampin, polymyxin B nonapeptide, and paenipeptin analogues 1 and 15 against 10 carbapenem-resistant pathogens

| Species or antibiotic-resistant clinical isolatea | MIC (μg/ml) for: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarithromycin | Rifampin | Polymyxin B nonapeptide | Analogue 1 with: |

Analogue 15 with: |

|||

| No FBSb | 10% FBS | No FBS | 10% FBS | ||||

| A. baumannii | |||||||

| FDA-CDC AR 0037 | 16 | 2 | >32 | 8 | 16 | 8 | 4 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0052 | 4 | 1 | >32 | 2–4 | 2–4 | ≤0.5 | <0.5 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0063 | 16–32 | 1 | >32 | 8–32 | 32 | 0.5–4 | 2 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0070 | 2–4 | 1 | >32 | 2 | 2–8 | ≤0.5 | 0.5–1 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0083 | >32 | 32 | >32 | 32 | ≥32 | 8–16 | 4–8 |

| K. pneumoniae | |||||||

| FDA-CDC AR 0034 | >32 | 16 | >32 | ≥32 | >32 | ≥32 | >32 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0044 | >32 | 32 | >32 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 16–32 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0068 | >32 | 32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 | >32 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0080 | >32 | >32 | >32 | 16 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0097 | >32 | 32 | >32 | >32 | 16–32 | >32 | 16–32 |

From the FDA-CDC Antimicrobial Resistance Isolate Bank.

The MIC of paenipeptin analogues 1 and 15 was tested with or without 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

TABLE 3.

MIC of clarithromycin and rifampin in combination with PMBN or paenipeptin analogues 1 and 15 against 10 carbapenem-resistant pathogensa

| Species or antibiotic-resistant clinical isolate | MIC (µg/ml) forb: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clarithromycin in the presence of: |

Rifampin in the presence of: |

|||||

| PMBN | Analogue 1 | Analogue 15 | PMBN | Analogue 1 | Analogue 15 | |

| A. baumannii | ||||||

| FDA-CDC AR 0037 | 0.125–0.25 | 0.0313 | ≤0.0019 | 0.25 | 0.0039 | ≤0.0019 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0052 | 0.0313–0.0625 | —c | — | 0.0625–0.125 | — | — |

| FDA-CDC AR 0063 | 0.5–1 | 0.0313 | — | 0.125 | ≤0.0019 | — |

| FDA-CDC AR 0070 | 0.25–0.5 | — | — | 0.0625–0.125 | — | — |

| FDA-CDC AR 0083 | 32 | 16 | 1–4 | 8 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.0313–0.0625 |

| K. pneumoniae | ||||||

| FDA-CDC AR 0034 | >32 | 0.25 | 0.125–0.5 | 1 | ≤0.0019 | ≤0.0019 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0044 | 4 | 0.0156 | 0.0078–0.0156 | 2 | ≤0.0019 | ≤0.0019 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0068 | >32 | 1 | >32 | 2–8 | 0.0039–0.0156 | 0.0039–0.0078 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0080 | 4 | 0.0313 | 0.0156 | >32 | 0.0625 | 0.0313 |

| FDA-CDC AR 0097 | 32 | 0.0313–0.0625 | 0.0078–0.0156 | 16 | 0.0039–0.0078 | 0.0019–0.0039 |

Clinical isolates from the FDA-CDC Antimicrobial Resistance Isolate Bank. PMBN, polymyxin B nonapeptide.

Paenipeptin analogue or PMBN at 4 μg/ml.

—, not tested because of no bacterial growth at the presence of paenipeptin analogues 1 or 15 alone at 4 μg/ml.

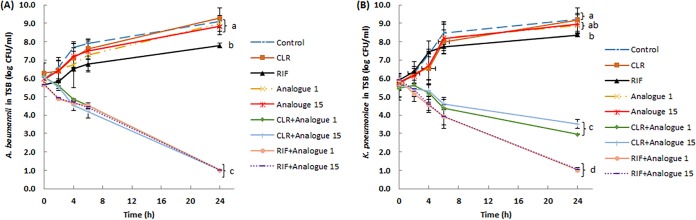

Time-kill kinetics assays were used to determine the bacteriostatic or bactericidal activity of clarithromycin or rifampin in the presence of paenipeptin analogues. Paenipeptin analogues, clarithromycin, and rifampin were used at therapeutically relevant concentrations in the time-kill kinetics assays. Bacterial viable counts were determined at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 24 h after antimicrobial treatment. Bacterial survival counts at 24-h endpoints were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's honest significant difference (HSD) tests using SPSS Statistics software (version 24; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). As shown in Fig. 2A, when used alone, paenipeptin analogues at 4 μg/ml and clarithromycin or rifampin at 1 μg/ml did not inhibit the growth of A. baumannii FDA-CDC AR 0063 in tryptic soy broth at 37°C; the bacterial population increased by 2.1 to 3.0 log within 24 h. Conversely, the cell population steadily declined over time when treated by paenipeptin analogue 1 or 15 in combination with clarithromycin or rifampin. The combined treatment resulted in a 4.7- to 5.1-log reduction within 24 h. A similar trend was observed for a second carbapenem-resistant pathogen, K. pneumoniae FDA-CDC AR 0097 (Fig. 2B). Paenipeptin analogues, clarithromycin, or rifampin alone were not bactericidal at tested concentrations against K. pneumoniae FDA-CDC AR 0097; the combination of a paenipeptin analogue with clarithromycin reduced the cell counts by 2.1 to 2.5 log in 24 h, whereas the combination with rifampin produced a 4.9-log reduction within 24 h in tryptic soy broth (Fig. 2B). Therefore, paenipeptin analogues plus clarithromycin or rifampin were significantly superior to either single agent against both A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae in tryptic soy broth.

FIG 2.

Time-kill curves of carbapenem-resistant pathogens with exposure to analogue 1 or 15 alone at 4 μg/ml and in combination with clarithromycin (CLR) or rifampin (RIF) at 1 μg/ml in tryptic soy broth (TSB). (A) Acinetobacter baumannii FDA-CDC AR0063; (B) Klebsiella pneumoniae FDA-CDC AR0097. Values are expressed as means (number of independent biological replicates, at least 3), and error bars represent standard deviations. Means at 24-h endpoints with different letters are significantly different between groups (P < 0.05).

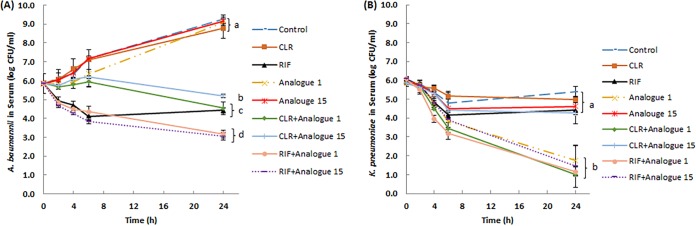

Paenipeptin analogues 1 and 15 were stable in 95% human serum for up to 24 h in vitro (data not shown). To further test the therapeutic potential of paenipeptin analogues, time-kill kinetics assays of paenipeptins alone or in combination with other antibiotics were performed in 95% human serum in vitro. Without antimicrobial treatment, the population of A. baumannii FDA-CDC AR 0063 cells increased from 5.8 log to 9.3 log within 24 h. Rifampin at 4 μg/ml resulted in 1.4-log reduction of the cell population in 24 h, but other single-antibiotic treatment was not effective (Fig. 3A). Rifampin alone also showed similar or slightly better activity compared with that of the combined treatments of clarithromycin and paenipeptin analogue 1 or 15. Moreover, the combination of rifampin with paenipeptin analogue 1 or 15 decreased the bacterial population by 2.7 log, which was significantly better than the outcome of each single-agent treatment. Similarly, paenipeptin analogues 1 and 15 significantly potentiated clarithromycin against A. baumannii FDA-CDC AR 0063, leading to 1.3- and 0.7-log reductions, respectively, in 24 h in 95% human serum (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

Time-kill curves of carbapenem-resistant pathogens with exposure to analogue 1 or 15 alone at 4 μg/ml and in combination with clarithromycin (CLR) or rifampin (RIF) at 4 μg/ml in 95% human serum in vitro. (A) Acinetobacter baumannii FDA-CDC AR0063; (B) Klebsiella pneumoniae FDA-CDC AR0097. Values are expressed as means (number of independent biological replicates, at least 3), and error bars represent standard deviations. Means at 24-h endpoints with different letters are significantly different between groups (P < 0.05).

Human serum exhibited a bacteriostatic effect against K. pneumoniae FDA-CDC AR0097; the bacterial cell counts over 24 h never exceeded that of the initial bacterial population. We also observed that human serum inhibited the growth of a reference strain, K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 (data not shown). Similarly, other researchers reported the inhibitory effect of human serum against certain K. pneumoniae strains (7, 8). The presence of human serum enhanced the bactericidal efficacy of paenipeptin analogue 1, which inactivated 4.2 log of K. pneumoniae cells within 24 h (Fig. 3B). The combination of analogue 1 with clarithromycin or rifampin resulted in 4.9-log reduction in bacterial population in 24 h, even though the combined treatment was not statistically better than analogue 1 alone in 95% human serum. Paenipeptin analogue 15, which differs from analogue 1 at the N terminus, did not show bactericidal activity or potentiate clarithromycin against K. pneumoniae FDA-CDC AR0097 in human serum. However, when analogue 15 was combined with rifampin, a 4.6-log reduction was achieved within 24 h (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the combination of analogue 15 and rifampin was significantly better than the respective single treatments against K. pneumoniae in 95% human serum.

In conclusion, paenipeptin analogues can expand the antimicrobial spectrum and enhance the antibiotic activities of clarithromycin and rifampin. These results suggested that paenipeptin analogues in combination with other antibiotics may be an alternative therapeutic option to treat infections caused by antibiotic-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, including those caused by carbapenem-resistant pathogens. The therapeutic efficacy of the combined treatment will be evaluated using animal models.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Arkansas Biosciences Institute, the major research component of the Arkansas Tobacco Settlement Proceeds Act of 2000. The antibiotic-resistant strains were kindly provided by the FDA-CDC Antimicrobial Resistance Isolate Bank.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vaara M. 1992. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol Rev 56:395–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Diseased Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zabawa TP, Pucci MJ, Parr TR, Lister T. 2016. Treatment of Gram-negative bacterial infections by potentiation of antibiotics. Curr Opin Microbiol 33:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang E, Yang X, Zhang L, Moon SH, Yousef AE. 2017. New Paenibacillus strain produces a family of linear and cyclic antimicrobial lipopeptides: cyclization is not essential for their antimicrobial activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364:fnx049. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moon SH, Zhang X, Zheng G, Meeker DG, Smeltzer MS, Huang E. 2017. Novel linear lipopeptide paenipeptins with potential for eradicating biofilms and sensitizing Gram-negative bacteria to rifampicin and clarithromycin. J Med Chem 60:9630–9640. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang E, Yousef AE. 2014. Paenibacterin, a novel broad-spectrum lipopeptide antibiotic, neutralises endotoxins and promotes survival in a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-induced sepsis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 44:74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benge GR. 1988. Bactericidal activity of human serum against strains of Klebsiella from different sources. J Med Microbiol 27:11–15. doi: 10.1099/00222615-27-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLeo FR, Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Freedman B, Dorward DW, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN. 2017. Survival of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 258 in human blood. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02533-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02533-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]