Solithromycin is a novel fluoroketolide antibiotic which was under investigation for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP). A phase 1 study was performed to characterize the pharmacokinetics (PK) and safety of solithromycin in children.

KEYWORDS: solithromycin, pharmacokinetics, pediatrics, antibiotics, safety

ABSTRACT

Solithromycin is a novel fluoroketolide antibiotic which was under investigation for the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP). A phase 1 study was performed to characterize the pharmacokinetics (PK) and safety of solithromycin in children. Eighty-four subjects (median age, 6 years [age range, 4 days to 17 years]) were administered intravenous (i.v.) or oral (capsules or suspension) solithromycin (i.v., 6 to 8 mg/kg of body weight; capsules/suspension, 14 to 16 mg/kg on days 1 and 7 to 15 mg/kg on days 2 to 5). PK samples were collected after the first and multidose administration. Data from 83 subjects (662 samples) were combined with previously collected adolescent PK data (n = 13; median age, 16 years [age range, 12 to 17 years]) following capsule administration to perform a population PK analysis. A 2-compartment PK model characterized the data well, and postmenstrual age was the only significant covariate after accounting for body size differences. Dosing simulations suggested that 8 mg/kg i.v. daily and oral dosing of 20 mg/kg on day 1 (800-mg adult maximum) followed by 10 mg/kg on days 2 to 5 (400-mg adult maximum) would achieve a pediatric solithromycin exposure consistent with the exposures observed in adults. Seventy-six treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 40 subjects. Diarrhea (6 subjects) and infusion site pain or phlebitis (3 subjects) were the most frequently reported adverse events related to treatment. Two subjects experienced TEAEs of increased hepatic enzymes that were deemed not to be related to the study treatment. (The phase 1 pediatric studies discussed in this paper have been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under identifiers NCT01966055 and NCT02268279.)

INTRODUCTION

Solithromycin is a novel fluoroketolide antibiotic that was under investigation for use in adults and children (1, 2). This antibiotic's mechanism of action is mediated through inhibition of bacterial protein synthesis (3). Specifically, it has a unique pattern of binding to ribosomal domains II and V, as well as to the peptide tunnel, of the 23S component of the 50S ribosomal subunit (3). In vitro, solithromycin has activity against Gram-positive organisms, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; Gram-negative organisms, such as Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis; and atypical pathogens, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Legionella pneumophila (4–8). In animal models, solithromycin was efficacious against Streptococcus pneumoniae, beta-hemolytic streptococci, Mycobacterium spp., and Enterococcus faecalis, among others (sponsor data [Melinta Therapeutics, Inc., Chapel Hill, NC] on file).

In vitro, solithromycin is both a substrate and an inhibitor of cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) (9). The active, primary side chain metabolites in human plasma are N-acetyl solithromycin and a metabolite resulting from the loss of an aminophenyl-1,2,3-triazole group (CEM-214); however, in humans, neither metabolite achieves plasma concentrations that are ≥10% of those of the parent compound (10). An adult population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) model, which incorporated autoinhibition of clearance (CL), was used to support oral dosing of 800 mg on day 1 followed by 400 mg daily on days 2 to 5 and intravenous (i.v.) dosing of 400 mg daily (with no front loading on day 1) in subjects with community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) (11, 12). This oral regimen and i.v.-to-oral dosing regimens were shown to be noninferior to moxifloxacin in adult phase 3 trials evaluating the use of solithromycin for the treatment of CABP (13, 14). In adults receiving 800 mg on day 1 followed by 400 mg daily on days 2 to 5 (13), the geometric mean for the day 1 area under the concentration-versus-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24) and maximal drug concentration (Cmax) were 18.9 μg · h/ml (coefficient of variation [CV], 71.8%) and 1.54 μg/ml (CV, 70.2%), respectively (sponsor data [Melinta Therapeutics, Inc., Chapel Hill, NC] on file). On day 4, the AUC0–24 and Cmax were 12.6 μg · h/ml (CV, 80.5%) and 1.05 μg/ml (CV, 73.6%), respectively. In a separate phase 3 study, adult subjects received 400 mg i.v. on day 1 followed by 400 mg i.v. daily and were permitted to switch to oral treatment when clinically indicated (14). The AUC0–24 and Cmax on the first day of i.v. dosing were 21.5 μg · h/ml (CV, 43.8%) and 3.08 μg/ml (CV, 35.1%), respectively; on the first day of oral dosing (800 mg), the AUC0–24 and Cmax were 26.9 μg · h/ml (CV, 62.4%) and 2.20 μg/ml (CV, 54.0%), respectively (sponsor data [Melinta Therapeutics, Inc., Chapel Hill, NC] on file).

We previously performed a phase 1 study to assess the pharmacokinetics (PK) and safety of solithromycin in a small cohort of adolescents with suspected or confirmed bacterial infections (2). In that study, oral dosing (capsules) of a 12-mg/kg of body weight (WT) dose (800 mg maximum) on day 1 and 6 mg/kg (400 mg maximum) on days 2 to 5 resulted in drug exposure comparable to that observed in adults. We performed a follow-up phase 1, open-label, multicenter study to determine the PK and safety of i.v. and oral (capsules and suspension) solithromycin as add-on therapy in children ranging from infants (postmenstrual age [PMA] ≥ 37 weeks) to adolescents with a suspected or confirmed bacterial infection. Using the data collected from both phase 1 studies, we performed a PopPK analysis to identify dosing for a follow-up phase 2/3 study that was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of solithromycin across pediatric age groups.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.

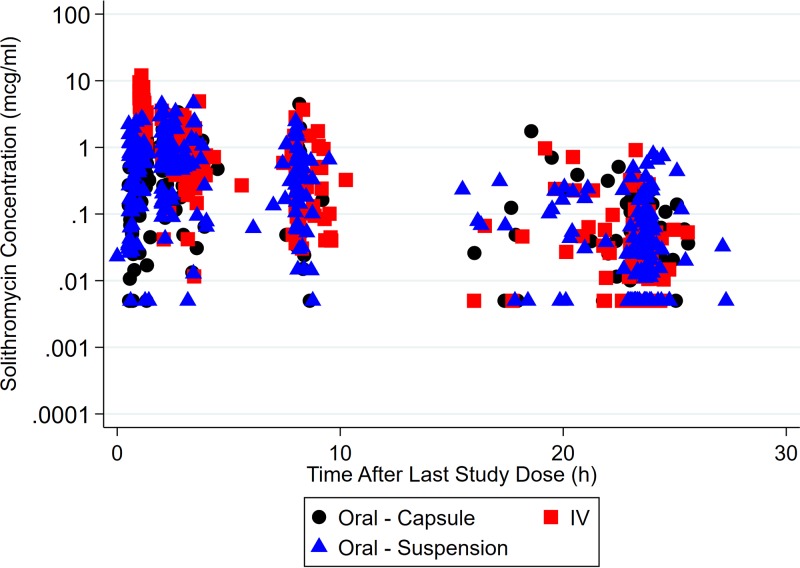

Data collected from 96 subjects were used for PopPK model development (Table 1): 13 subjects from a previously published study (CE01-119) of adolescents (2) and 83 subjects from the follow-up study performed in term infants to adolescents (CE01-120). (Although 84 subjects were enrolled in the latter study, 1 subject did not contribute any PK data [the subject contributed only safety information].) A total of 780 plasma PK samples (118 from CE01-119 and 662 from CE01-120) were collected. No PK samples were excluded from the analysis. A total of 96 (12.3%) drug concentrations were below the quantification limit (BQL), and a value equal to the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) divided by 2 was imputed for these samples. The median number of samples collected per participant was 9 (range, 2 to 11). The median number of doses recorded per participant was 2 (range, 1 to 5). The numbers of plasma concentration measurements following capsule, suspension, and i.v. administration were 210 (27%), 290 (37%), and 280 (36%), respectively. A concentration-versus time-plot for solithromycin is shown in Fig. 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics stratified by age groupd

| Characteristic | Value(s) for subjects in the following age groups: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to <2 yr | 2 to <6 yr | 6 to <12 yr | 12 to 17 yr | Total | |

| No. of subjects | 22 | 17 | 34 | 23 | 96 |

| Median (range) wt (kg) | 8.05 (3.8–14.6) | 14.5 (11.0–25.4) | 27.85 (11.3–105.0) | 63.0 (28.6–84.0) | 23.0 (3.8–105.0) |

| Median (range) postnatal age (yr) | 0.6 (0.0–1.8) | 3.1 (2.0–5.0) | 7.5 (6.0–11.0) | 15.0 (12.0–17.0) | 7.0 (0.0–17.0) |

| Median (range) PMA (wk)a | 71.6 (39.6–144.3) | 234 (147.0–344.4) | 473.6 (356.0–653.0) | 865 (666.1–972.1) | 411.0 (39.6–972.1) |

| No. (%) of female subjects | 10 (45) | 8 (47) | 17 (50) | 18 (78) | 53 (55) |

| No. (%) of white subjects | 20 (91) | 13 (76) | 28 (82) | 20 (87) | 81 (84) |

| No. (%) of non-Hispanic subjects | 18 (82) | 16 (94) | 25 (74) | 18 (78) | 77 (80) |

| Median (range) serum creatinine concn (mg/dl) | 0.30 (0.10–0.77) | 0.30 (0.12–0.61) | 0.39 (0.20–0.88) | 0.60 (0.32–1.2) | 0.39 (0.10–1.2) |

| Median (range) AST concn (U/liter) | 36.0 (18.0–97.0) | 27.0 (11.0–84.0) | 27.0 (14.0–93.0) | 24.0 (13.0–96.0) | 28.0 (11.0–97.0) |

| Median (range) ALT concn (U/liter) | 22.0 (9.0–115) | 14.0 (5.0–84.0) | 24.0 (6.0–73.0)b | 27.0 (6.0–205.0) | 23.0 (5.0–205.0)c |

| Median (range) albumin concn (g/dl) | 3.5 (2.3–4.6) | 3.2 (1.4–4.5) | 3.6 (1.5–4.9) | 3.7 (2.3–4.8) | 3.6 (1.4–4.9) |

Postmenstrual age (PMA) was calculated as postnatal age (PNA; in weeks) + gestational age (GA; in weeks), calculated using the value at the time of the first study dose. Missing GA was imputed as 40 weeks for the calculation of PMA.

Data for this variable were available for 33 subjects.

Data for this variable were available for 95 subjects.

Descriptive statistics were calculated on the basis of the value at the time of the first dose. AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

FIG 1.

Solithromycin concentration versus time after the last dose on a semilog scale.

Population pharmacokinetic analysis.

Various PK structural models were evaluated, including a 1-compartment model, a 2-compartment model (change in objective function value [ΔOFV] = −823.8 points from the 1-compartment model), and a 3-compartment model (ΔOFV = −841.1 points from the 1-compartment model), all with linear elimination and first-order absorption. Also, an autoinhibition of CL model (ΔOFV = 1,268.4 points from the 1-compartment model) and a nonlinear absorption model (Michaelis-Menten) with first-order elimination (ΔOFV = −570.7 points from the 1-compartment model) were evaluated (11, 15). Based on the model selection criteria, a 2-compartment model with linear elimination and first-order absorption with an oral absorption lag time provided adequate fitting of the data, was more stable, and had more reliable estimates than the 3-compartment model. Scaling of the CL and volume of distribution (V) parameters by actual body weight (WT) using a fixed-exponent allometric relationship (exponent = 0.75 for CL and 1 for V) resulted in a 100.9-point reduction in the OFV compared to scaling without an allometric model. When the allometric exponents were estimated, the CL and V exponents were 0.709 and 0.831, respectively (ΔOFV = −0.89 points). Since this did not significantly improve the model, the fixed allometric exponents were used for further covariate model development.

Use of a sigmoidal maximum-effect (Emax) maturation function with PMA resulted in the largest OFV drop (−17.9 points) overall among all of the covariate relationships tested, including other functions based on age (e.g., power and exponential functions using PMA or postnatal age [PNA]). Thereafter, the total bilirubin concentration on the central compartment volume of distribution (Vc) resulted in a significant drop in the OFV (−5.19 points); however, this covariate did not meet statistical significance and was removed from the model in the backward elimination step. Thus, the final model included WT and a sigmoidal maturation relationship between PMA and CL. This sigmoidal relationship characterized an increase in CL with PMA, and 50% of the adult CL was estimated to occur at approximately 52.6 weeks PMA. Inclusion of PMA as a covariate for CL did not change the interindividual variability (IIV) on this parameter (base model IIV, 81.9%; final model IIV, 81.8%), but it was included in the model, as developmental changes in CYP3A expression are expected to affect solithromycin CL.

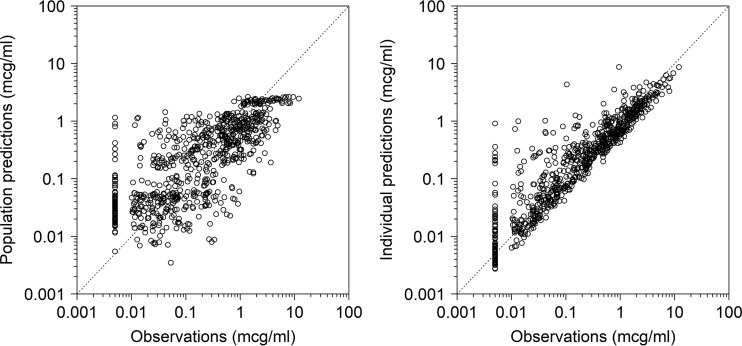

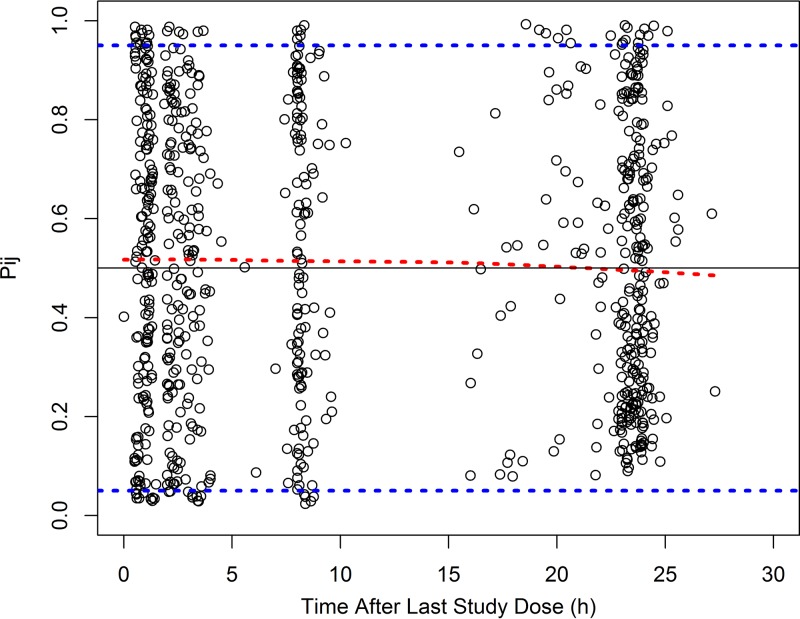

The final PopPK model parameter estimates are shown in Table 2. Shrinkage in the IIV terms (ETAs) for CL, Vc, and the peripheral compartment volume of distribution (Vp) were 1.3%, 5.0%, and 17.0% for the final model, respectively, while epsilon shrinkage was 8.1%. The observations versus population and individual predictions for the final model are shown in Fig. 2. The visual predictive check revealed a reasonable fit between the observed and predicted solithromycin concentrations. A uniform distribution of calculated observation percentiles was observed at earlier time points, where the data points were relatively abundant (Fig. 3). Overall, 8.2% of the observed concentrations fell outside the 90% prediction interval.

TABLE 2.

Parameter estimates for the final solithromycin population pharmacokinetic modela

| Parameter | Final model |

Bootstrap analysis (n = 1,000)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | RSE (%) | 2.5th percentile | Bootstrap · median | 97.5th percentile | |

| Structural model | |||||

| Ka (h−1) | 0.381 | 14 | 0.294 | 0.388 | 0.538 |

| CLPOP,70 kg (liters/h) | 55.0 | 15 | 40.2 | 51.3 | 69.8 |

| VcPOP,70 kg (liters) | 162 | 13 | 113.7 | 156.3 | 223.1 |

| QPOP,70 kg (liters/h) | 23.4 | 30 | 9.1 | 26.1 | 46.2 |

| VpPOP,70 kg (liters) | 119 | 14 | 90.2 | 122.4 | 161.3 |

| F (%), capsule | 69.1 | 19 | 41.1 | 70.2 | 94.1 |

| F (%), suspension | 52.9 | 20 | 34.1 | 51.9 | 75.8 |

| Lag (h), capsule | 0.494 | 2 | 0.458 | 0.495 | 0.564 |

| Lag (h), suspension | 0.365 | 24 | 0.196 | 0.388 | 0.478 |

| Hill | 1.1 | 63 | 0.612 | 1.6 | 7.1 |

| TM50 (wk) | 52.6 | 37 | 32.6 | 50.2 | 68.5 |

| IIV (% CV) | |||||

| IIV CL | 81.9 | 8 | 67.8 | 82.3 | 105.2 |

| Covariance CL-Vc | 0.569 | 25 | 0.310 | 0.558 | 1.5 |

| IIV Vc | 89.6 | 13 | 58.3 | 87.6 | 159.0 |

| Covariance Vc-Vp | 0.262 | 38 | 0.057 | 0.247 | 0.563 |

| IIV Vp | 53.7 | 28 | 31.5 | 56.3 | 108.0 |

| Covariance CL-Vp | 0.355 | 38 | 0.110 | 0.357 | 0.849 |

| Residual error (% proportional error) | 53.9 | 9 | 48.8 | 52.8 | 57.7 |

CLPOP,70 kg, population clearance estimate scaled to a 70-kg adult; covariance CL-Vc, covariance between CL and Vc; covariance CL-Vp, covariance between CL and Vp; covariance Vc-Vp, covariance between Vc and Vp; F, bioavailability; Hill, Hill coefficient for the sigmoidal maturation function; IIV CL, interindividual variability in drug clearance; IIV Vc and Vp, interindividual variability in the central and peripheral compartments, respectively; Ka, absorption rate constant; Lag, lag time (in hours) in drug absorption; QPOP,70 kg, population intercompartmental clearance estimate scaled to a 70-kg adult; RSE, relative standard error; TM50, maturation half-life calculated as a function of postmenstrual age (weeks); VcPOP,70 kg, population volume of distribution in the central compartment estimate scaled to a 70-kg adult; VpPOP,70 kg, population volume of distribution in the peripheral compartment estimate scaled to a 70-kg adult.

A total of 1,000 bootstrap runs were performed (total minimized successfully = 832 [83%]).

FIG 2.

Observations versus population and individual predictions for the final solithromycin population pharmacokinetic model. The dashed gray line denotes the line of unity.

FIG 3.

Standardized visual predictive check (SVPC) plot of solithromycin observation percentiles versus time after the last dose for the final population pharmacokinetic model. The dashed blue lines represent the 5th and 95th percentiles of the model-predicted Pij, where Pij is the percentile of the jth observation for the ith subject. The red dashed line is the 50th percentile of the model-predicted Pij. The black line corresponds to a Pij of 0.5. Open circles are the calculated Pij for each observation. The percentage of observed concentrations that were outside the 90% prediction interval was 8.2%.

Dosing simulations.

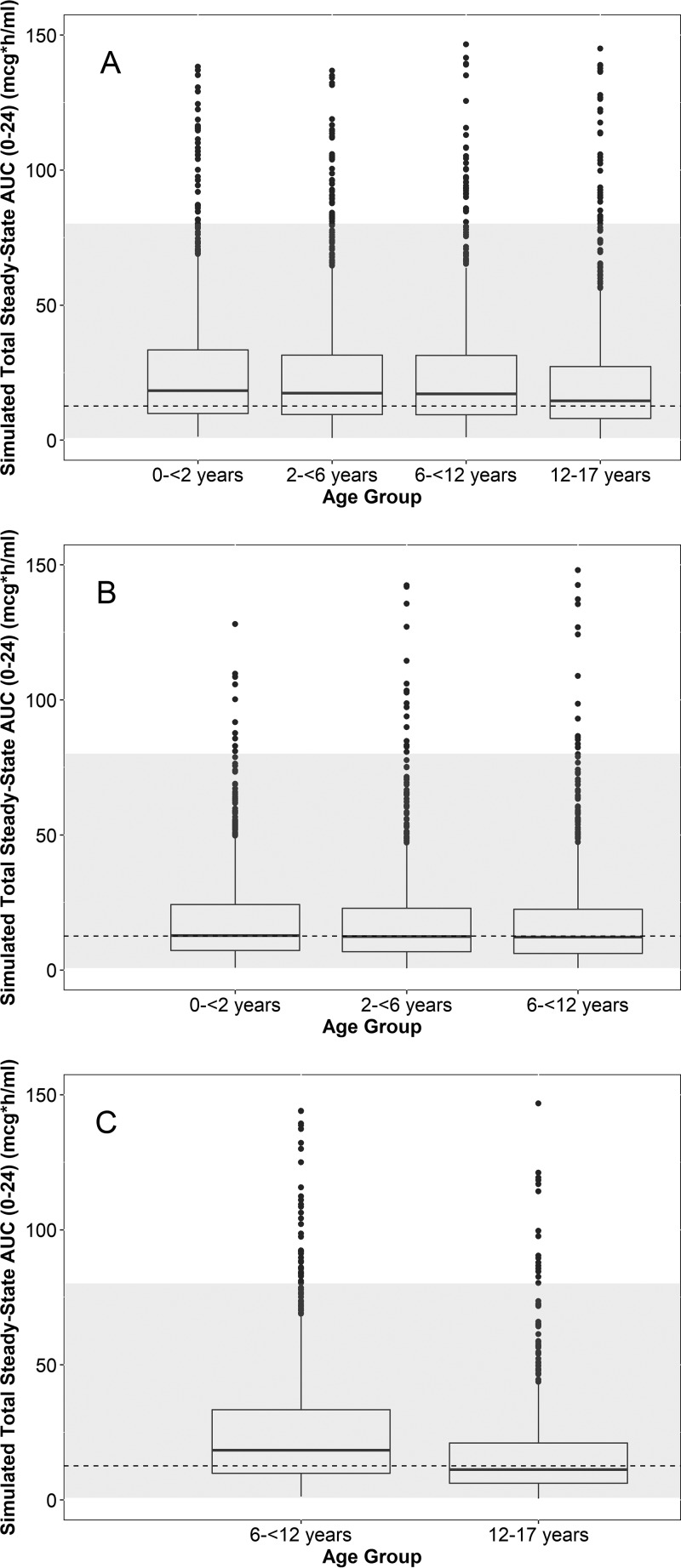

AUC0–24 and Cmax were simulated for virtual subjects between 0 and <2 years, 2 and <6 years, 6 and <12 years, and 12 and 17 years of age following multiple i.v. and oral (capsules and suspension) dosing (1,000 virtual subjects for each age group-formulation cohort) and compared to the adult estimates. Box plots of the simulated day 1 and day 5 AUC0–24 stratified by formulation and age group are shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material and Fig. 4, respectively. For i.v. dosing, an 8-mg/kg daily dosing regimen (400-mg adult maximum) resulted in both day 1 and day 5 simulated AUC0–24 estimates that were generally within the adult range across age groups. For the suspension and capsule formulations, a 20-mg/kg day 1 dose (800-mg adult maximum) followed by 10 mg/kg daily (400-mg adult maximum) on days 2 through 5 resulted in simulated day 1 and day 5 AUC0–24 estimates across age groups comparable to those observed in adults. Capsule doses were rounded upwards to the nearest 200 mg (based on the availability of this dosage strength for a follow-up phase 2/3 study). The simulated day 1 and day 5 Cmax stratified by formulation and age group are shown in Fig. S2 and S3, respectively, and were generally within the adult range. A summary of the solithromycin dosing regimens selected for further evaluation is provided in Table 3.

FIG 4.

Box plots of the simulated day 5 area under the concentration-versus-time curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24) across age groups using 8 mg/kg i.v. daily (A) (400 mg maximum) and 20 mg/kg on day 1 (800 mg maximum) followed by 10 mg/kg on days 2 to 5 (400 mg maximum) for the suspension (B) and capsules (C). Capsule doses were rounded upwards to the nearest 200 mg. The dashed line and gray region denote the geometric mean and range of the adult exposures in the phase 3 studies, respectively. Because phase 3 adult studies evaluated daily oral dosing and an i.v.-to-oral formulation switch, the same geometric mean and range (estimates following multiple oral dosing) are visualized across all 3 panels. The dashed lines used in all panels represent the geometric mean day 4 exposure following capsule daily dosing in the phase 3 study. The lower and upper hinges of the box plot correspond to the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The upper and lower whiskers extend to the largest and smallest value no further than 1.5 · interquartile range (IQR), respectively. Closed circles represent outlier values outside 1.5 · IQR. Simulated extreme outlier values of >150 μg · h/ml (1.2% and <0.5% of the simulated data points for the i.v. and oral [suspension/capsule] formulations, respectively) are not plotted for ease of visualization.

TABLE 3.

Dosing to be evaluated in a follow-up phase 2/3 studye

| Age (yr) | Route | Formulation | Loading dose | Maintenance dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 to 17 | i.v. | Solution | NA | 8 mg/kga |

| 12 to 17 | p.o. | Capsulesb | 20 mg/kg or 800 mgc | 10 mg/kg or 400 mgd |

| 6 to <12 | p.o. | Capsulesb | 20 mg/kg or 800 mgc | 10 mg/kg or 400 mgd |

| 6 to <12 | p.o. | Suspension | 20 mg/kgc | 10 mg/kgd |

| 6 to <12 | i.v. | Solution | NA | 8 mg/kga |

| 2 to <6 | p.o. | Suspension | 20 mg/kgc | 10 mg/kgd |

| 2 to <6 | i.v. | Solution | NA | 8 mg/kga |

| 0 to <2 | p.o. | Suspension | 20 mg/kgc | 10 mg/kgd |

| 0 to <2 | i.v. | Solution | NA | 8 mg/kg |

Eight milligrams per kilogram with a 400-mg daily maximum.

Capsule doses would be rounded upwards to the nearest 200 mg.

Twenty milligrams per kilogram with an 800-mg day 1 maximum dose for children with weights of <40 kg and an 800-mg day 1 dose for children with weights of ≥40 kg.

Ten milligrams per kilogram with a 400-mg day 2 to 5 maximum dose for children with weights of <40 kg and 400-mg day 2 to 5 doses for children with weights of ≥40 kg.

i.v., intravenous; NA, not applicable; p.o., oral.

Safety.

Safety data for adolescents enrolled in the CE01-119 study were previously published (2). Safety data for solithromycin administered daily for up to 5 days were collected for the 84 subjects ranging in age from 4 days to 17 years enrolled in the CE01-120 study: 23 subjects ages 0 to <2 years, 17 subjects ages 2 to <6 years, 34 subjects ages 6 to <12 years, and 10 subjects ages 12 to 17 years. In the CE01-120 study, 76 treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported in 40 (47.6%) subjects; 15/84 (17.9%) reported an adverse event that was related to solithromycin. The following TEAEs were considered related to solithromycin: diarrhea in 6/84 (7.1%) subjects; infusion site pain or phlebitis in 3/84 (3.6%) subjects; and headache, abdominal pain, infusion site thrombosis, infusion site extravasation, rash, and vomiting, each in 1/84 (1.2%) subjects. One 6-month-old subject with congenital cyanotic heart disease and recent corrective surgery had a serious adverse event (atrial tachycardia without hemodynamic instability) that was considered study drug related. The event occurred 1 day after the first dose of study treatment. Approximately 11 h after the second study dose, electrocardiography showed atrial tachycardia. A loading dose of digoxin was administered, with reversion to sinus rhythm. Solithromycin was discontinued, and the event resolved.

There were 2 subjects with reported TEAEs of increased hepatic enzymes. The first subject (male, 3 years of age, i.v. formulation) had alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values elevated to a peak of 6.2 times the upper limit of normal (6.2×ULN) from a normal value (less than or equal to the ULN) at the baseline from day 5 through unscheduled visits on day 15. This subject had an aspartate aminotransferase (AST) baseline value that was high (greater than the ULN to 2×ULN) and then was elevated to a peak of 8.6×ULN from day 5 through unscheduled visits on day 11. Subsequent aminotransferase values were diminished from the highest level but still elevated (<2×ULN) through follow-up on day 18. The second subject (female, 0.6 year of age, oral suspension formulation) had baseline ALT and AST values that were elevated approximately 2×ULN to 3×ULN. Then, ALT values increased to a peak of 13.8×ULN and AST values increased to a peak of 5.5×ULN on day 18, with elevations diminishing but remaining greater than the ULN through day 77. For both subjects, the increase in hepatic enzymes was deemed unrelated to the study treatment. In addition to these 2 subjects with a TEAE of increased hepatic enzymes, there was 1 additional subject (male, 10 years of age, oral suspension formulation) with an ALT or AST elevation of >3×ULN at the follow-up visit from normal values at baseline. On day 5, this patient had an ALT value within the normal range, with the AST value being elevated to 1.3×ULN. At follow-up 11 days later on day 16, the ALT value was elevated to 2.7×ULN and the AST value was elevated further to 4.3×ULN. No adverse event of increased hepatic enzymes was issued for this subject, who initiated chemotherapy for leukemia on day 9.

Across all age groups in the total safety population (n = 84), the majority of subjects (>80%) did not have postbaseline changes in hepatic enzymes, total bilirubin, and/or direct bilirubin that entailed shifts in values from normal to greater than the ULN. A summary of the shift from baseline to the highest postbaseline value for ALT, AST, and total bilirubin is provided in Table 4. The cumulative area under the concentration-versus-time curve from 0 h to the time of a laboratory measurement (AUC0–t) versus AST, ALT, and total bilirubin values (measured >24 h after the first dose) is shown in Fig. S4 to S6.

TABLE 4.

Shift from baseline to the highest postbaseline value for hepatic enzymes and bilirubina

| Baseline result | Highest postbaseline result | No. of subjects of the following age with the indicated result/total no. of subjects tested (%): |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects ages 0 to <2 yr (n = 23) | All subjects ages 2 to <6 yr (n = 17) | All subjects ages 6 to <12 yr (n = 34) | Subjects ages 12 to 17 yr receiving treatment i.v. (n = 10) | All subjects (n = 84) | ||

| ALT concn (U/liter) | ||||||

| Normal (≤ULN) | ≥3×ULN to 10×ULN | 0 | 1/13 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 1/63 (1.6) |

| Overall | ≥3×ULN to 10×ULN | 0 | 1/16 (6.3) | 0 | 0 | 1/74 (1.4) |

| ≥10×ULN | 1/19 (5.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/74 (1.4) | |

| AST concn (U/liter) | ||||||

| Normal (≤ULN) | ≥3×ULN to 10×ULN | 0 | 0 | 1/23 (4.3) | 0 | 1/58 (1.7) |

| Overall | ≥3×ULN to 10×ULN | 1/19 (5.3) | 1/16 (6.3) | 1/29 (3.4) | 0 | 3/74 (4.1) |

| ≥10×ULN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Bilirubin (total) concn (mg/dl) | ||||||

| Normal (≤ULN) | >ULN to 2×ULN | 1/20 (5.0) | 1/15 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 2/71 (2.8) |

| Overall | ≥3×ULN to 10×ULN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥10×ULN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; i.v., intravenous; ULN, upper limit of normal.

DISCUSSION

We combined data from 2 phase 1 pediatric studies to characterize the PopPK of solithromycin across pediatric age groups. The PopPK of solithromycin in adults has been previously characterized using available plasma and epithelial lining fluid (ELF) collected in phase 1 and 2 studies (11, 12, 16). In these adult studies, a 3-compartment PopPK model (central, peripheral, and ELF compartments) with autoinhibition of CL via an effect compartment was found to describe the adult PK data well. This pediatric study also found that a 2-compartment model characterized the pediatric plasma concentration data well (no ELF data were collected). However, modeling of autoinhibition in solithromycin CL in our pediatric analyses did not improve the data fit. It is possible that we were not able to account for this autoinhibition in solithromycin CL due to developmental changes in CYP3A expression, the relatively sparse sampling nature of our study, and/or a shorter duration of treatment in children relative to that in adults. Due to impending hospital discharge, 10.3%, 36.1%, 16.4%, and 35.1% of pediatric subjects in our studies had multiple-dose PK assessments on days 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively (2.1% had a single dose), whereas all adult studies had dosing of at least 5 days.

A covariate analysis was performed to identify covariates that explain IIV in solithromycin PK. A sigmoidal maturation function using PMA was used to account for developmental changes in CL. This sigmoidal Emax function allows for a gradual maturation in drug CL in neonates and infants while attaining an adult CL in older age groups (17). The maturation half-life (i.e., maturation half-life calculated as a function of postmenstrual age [TM50]) and Hill factor for this solithromycin data set were 52.6 weeks and 1.09, respectively. These estimates are similar to previously reported estimates for other CYP3A substrates: 62.9 weeks and 2.94, respectively, for sirolimus; 39.7 weeks and 1 (the slope factor was not estimated), respectively, for lopinavir; and 35.7 weeks and 3.81, respectively, for levobupivacaine (17–20). These estimates are also in line with what is known about the ontogeny of CYP3A4, which appears in the first week of life and increases with age (reaching 50% of adult levels at about 0.31 year of age [assuming 40 weeks' gestation]) (21, 22). We estimated significant variability in solithromycin clearance (IIV CL = 81.9%), which could have been due to the inherent intersubject variability in drug concentration characteristics of macrolides (23–25); the timing of the PK sampling, which was not consistent and occurred on day 3, 4, or 5; and variability in the underlying disease of the subjects enrolled in this study.

Pediatric dosing recommendations for a follow-up phase 2/3 study were determined by comparing the solithromycin exposure observed in the phase 3 adult program to simulated values based on our final PopPK model. Although pronounced variability was observed in our simulated results, the dosing regimens selected for a follow-up study resulted in pediatric exposures that are comparable to those observed in adults. Across the age groups, there were simulated outlier values that fell outside the adult range, which is likely due to the high IIV in clearance. Additional PopPK analyses will be performed to externally evaluate the modeling results described herein.

Solithromycin was well tolerated in our study. Diarrhea and infusion site pain or phlebitis were the most frequently reported adverse events that were related to solithromycin (diarrhea in 6/84 [7.1%] subjects; infusion site pain or phlebitis in 3/84 [3.6%] subjects). Three subjects had reversible hepatic enzyme elevations >3×ULN that normalized without sequelae; 2 of these were reported as TEAEs that were deemed by the site investigator not to be related to the study treatment. Although there were limited subjects with hepatic enzyme elevations >3×ULN, when ALT, AST, and total bilirubin values were plotted against cumulative exposure, there were no trends noted (see Fig. S4 to S6 in the supplemental material). One 6-month-old subject with congenital cyanotic heart disease and recent corrective surgery experienced atrial tachycardia without hemodynamic instability that was considered study drug related and resolved following discontinuation of the study drug. The safety and tolerability profile of solithromycin in children enrolled in this study is consistent with prior findings in adults concerning the most commonly observed adverse events (AEs) and laboratory abnormalities. However, the frequency of elevations in liver enzymes was lower in our pediatric sample (3/74 [4.1%] had an ALT or AST level >3×ULN at a follow-up visit) than in adults (9.1% experienced ALT increases of >3×ULN in 1 phase 3 trial [14]), which may have been related to differences in the sensitivity of hepatocytes to the study drug, variability in the exposure of solithromycin in individual pediatric subjects, the duration of solithromycin treatment (30/84 [35.7%] subjects received a full 5 days of treatment), and/or differences in the underlying severity of illness between adults and children.

This study is not without a few limitations. First, after accounting for body weight, only PMA was identified to be a statistically significant covariate in our model; however, given that a large fraction of variability in CL remained unexplained, there may be other covariates that are important but did not rise to the level of statistical significance in our analyses. Second, more than 10% (12.3%) of the samples were BQL. Several approaches were evaluated, including using the M3 method and imputing all BQLs with LLOQ/2. The M3 method either did not minimize or was unstable; thus, imputed values of LLOQ/2 were used for all BQL samples. Although this approach is practical and resulted in a stable model, it may have led to the poor agreement between model predictions and imputed values for samples that were below the LLOQ. Third, we were unable to account for autoinhibition in the solithromycin CL, possibly due to the relatively sparse PK sampling in our study and/or a shorter duration of treatment relative to that in adults. These limitations may explain some of the notable bias in model predictions at the upper and lower ends of the concentration range.

In summary, overall, solithromycin was well tolerated in our study. PK data from 2 phase 1 pediatric studies were combined, which allowed us to characterize the disposition of solithromycin following both oral and i.v. administration across pediatric age groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population.

We collected PK samples used to develop a PopPK model in 2 separate phase 1, open-label, multicenter pediatric studies (CE01-119 and CE01-120; ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT01966055 and NCT02268279, respectively). In study CE01-119, the results of which have been previously published (2), we enrolled 13 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years (inclusive) with suspected or confirmed bacterial infections and administered solithromycin via oral administration (capsules) as an add-on therapy. In study CE01-120, infants and children aged 0 to 17 years who received solithromycin as add-on therapy (i.v., capsule, and suspension formulations) were eligible for enrollment. All infants were ≥37 weeks PMA.

In both studies, in addition to age requirements and the presence of a suspected or confirmed bacterial infection, inclusion criteria required that the subject be expected to survive his or her current illness. For both studies, the exclusion criteria were also similar: evidence or a history of a significant medical condition that would preclude study participation, bacterial meningitis (CE01-119 only), use of an investigational drug and/or therapy within 30 days, consumption of Seville oranges or products containing Seville orange components and/or herbal supplements in the previous 7 days, a serum creatinine (SCR) concentration of >2 mg/dl, a mean screening electrocardiogram QTcF (QT corrected for heart rate using Fridericia's method) of >450 ms (CE01-119 only), hepatic dysfunction evidenced by an ALT or AST level of >3×ULN or a direct bilirubin level greater than the ULN, use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support (CE01-119 only), treatment with prespecified CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., diltiazem) or inducers (e.g., rifampin), concomitant use of clarithromycin or erythromycin, a positive pregnancy test, breast-feeding for females, a history of intolerance or sensitivity to macrolide antibiotics, or a history of phenylketonuria (CE01-120 only).

We obtained written informed consent from the parent or other legally authorized representative and informed assent from the patient (if age appropriate, according to local requirements). All study sites had the protocol reviewed and approved by their institutional review boards. In CE01-119, the first adolescent was enrolled on 17 February 2014 and the last adolescent completed the study on 5 September 2014. In CE01-120, the first subject was enrolled on 3 March 2015 and the last subject completed the study on 12 October 2016.

Drug dosing and sample collection.

In CE01-119, adolescents were administered solithromycin via oral administration (capsules) as an add-on therapy (12 mg/kg of WT on day 1 [800-mg adult maximum] and 6 mg/kg daily on days 2 to 5 [400-mg adult maximum]) for up to 5 days (2). In CE01-120, solithromycin was given via i.v. and oral (suspension and capsules) administration (i.v., 6 to 8 mg/kg [400-mg adult maximum]; capsules/suspension, 14 to 16 mg/kg [800-mg adult maximum] on day 1 and 7 to 15 mg/kg [400-mg adult maximum] on days 2 to 5). In both studies, following oral administration (suspension and capsules), plasma PK samples were collected at 0.5 to 1.5, 2 to 4, 8 to 10, and 23 to <24 h after the first and multiple-dose administration of solithromycin. If the drug was administered via the i.v. route, the recommended PK collection time windows were at the end of infusion (within 10 min) and at 2 to 4, 8 to 10, and 23 to 24 h after the start of the study infusion. If the patient was discharged before study day 4 or 5, PK samples were collected on the day of discharge at these scheduled time points, as possible. When administered via the i.v. route, the study drug was infused over approximately 60 min.

Analytical methods.

For both studies, plasma PK samples were analyzed by a central laboratory (MicroConstants, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) using validated liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). A 10-μl aliquot was extracted using solid-phase extraction. A 96-well SPEC-C18 15-mg extraction plate (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a solid-phase extraction elution solution containing 0.1% formic acid in methanol-acetonitrile (50:50, vol/vol) were used. High-performance liquid chromatography conditions were as follows: injection volume, 20 μl; flow rate, 0.3 ml/min; solvent A (35%), 20 mM ammonium formate, 0.2% formic acid, 0.0002% citric acid in water; solvent B (65%), 0.1% formic acid in methanol-acetonitrile (50:50, vol/vol); and analysis time, 4 min. A Phenomenex (Torrance, CA, USA) Luna CN 100-Å column (150 by 2.0 mm, 5 μm) was used. The solithromycin LLOQ was 0.01 μg/ml. The solithromycin calibration range was 0.01 to 20 μg/ml. Accuracy and precision were within the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) bioanalytical assay validation criteria for both methods (e.g., ±15 to 20%). N-Acetyl solithromycin-d6 was used as the internal standard.

Population pharmacokinetic analysis.

Solithromycin concentration data collected from both phase 1 pediatric trials were merged and analyzed with a nonlinear mixed-effects modeling approach using the software NONMEM (version 7.2; Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA). PK data collected following i.v. and/or oral administration were simultaneously modeled. For samples with concentrations that were BLQ, the M3 method and imputing a value equal to LLOQ/2 were tested (26). The first-order conditional estimation method with interaction was used for all model runs. Run management was performed using Pirana (version 2.8.1) software (27). Visual predictive checks and bootstrap methods were performed with Perl-speaks-NONMEM (version 3.6.2) software (28). Data manipulation and visualization were performed using the software Stata (version 13.1; College Station, TX), R (version 3.0.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and RStudio (version 0.97.551; RStudio, Boston, MA, USA), with the packages lattice, Xpose4, and ggplot2 being used for the last software (29–31).

Based on visual inspection of the PK data and a review of the primary literature, 1-, 2-, and 3-compartment, autoinhibition via an effect compartment (11), and nonlinear absorption (Michaelis-Menten) models (15) were evaluated. IIV was assessed for PK model parameters using an exponential relationship (equation 1):

| (1) |

where Pij denotes the estimate of parameter j in the ith individual, θPop,j is the population value for parameter j, and ηij denotes the deviation from the average population value for parameter j in the ith individual. The random variable η is assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of zero and variance of ω2. A logit transform model was used to constrain the bioavailability (F) between 0 and 1 when IIV was estimated for F (32). Separate F terms were estimated for the suspension and capsule formulations. The off-diagonal covariance was tested for the CL and V IIV parameters. Proportional, additive, and combined (proportional plus additive) residual error models were evaluated (equations 2 to 4):

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where Cobs,ij is the jth observed solithromycin concentration in the ith individual, Cpred,ij is the jth predicted concentration in the ith individual, and εprop,ij and εadd,ij are random variables with a mean of zero and variances of σprop,ij2 and σadd,ij2, respectively.

The ability of the covariates to explain IIV for PK parameters was tested if a relationship was suggested by visual inspection of scatter and box plots (continuous and categorical variables, respectively) of the individual deviations from the population-typical value PK parameters (i.e., ETAs) versus covariates. The following covariates were explored: PNA, PMA, gestational age (GA), total bilirubin, serum creatinine (SCR), albumin (ALB), ALT, AST, ethnicity, race, and sex on CL and V. Missing GA was imputed with 40 weeks for the calculation of PMA. A forward inclusion (P < 0.05 and ΔOFV = >3.84 points) and backward elimination (P < 0.01 and ΔOFV = >6.63 points) approach was used to evaluate the statistical significance of relevant covariates.

Actual WT was assumed to be a significant covariate for CL and V and was included in the base model prior to assessment of the other covariates. The relationship between WT and PK parameters was characterized using a fixed-exponent allometric relationship for CL parameters and a linear scale for volume parameters (equations 5 to 6) (17). Scaling was based on a 70-kg standardized adult WT, as shown below. The exponents were fixed as shown in equations 5 and 6 below. However, we also evaluated the model's performance when estimating these exponents.

| (5) |

| (6) |

In equations 5 and 6, WTi denotes the body weight of individual participant i; CLPOP,70 kg and VPOP,70 kg are the population estimates of CL and V for a 70-kg adult, respectively; CLi and Vi are the estimates of CL and V for each participant i, respectively; and ETACL and ETAV are the IIV parameters for CL and V, respectively. The intercompartmental clearance parameter (Q70 kg) was also scaled to a 70-kg standardized weight according to equation 5, whereas the volume of the central compartment (Vc,70 kg) and the volume of the peripheral compartment (Vp,70 kg) were also scaled to a 70-kg standardized weight according to equation 6.

With the exception of WT, other continuous covariates were normalized to the population median value, as described in equation 7 or 8, whereas for categorical covariates, such as sex, the relationship shown in equation 9 was used.

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

where covi denotes the covariate value for individual i, covm is the population median covariate value, θcov is a parameter that represents the covariate effect, and CATVAR is a binary variable that takes on the value of 1 or 0.

The relationship between age (e.g., PMA) and CL was also tested as a sigmoidal Emax maturation function, as shown in equation 10 (17).

| (10) |

where FPMA denotes the fraction of the adult CL value, TM50 (maturation half-life) represents the value of PMA (weeks) when 50% of the adult CL is reached, and Hill (the Hill coefficient for the sigmoidal maturation model) is a slope parameter for the sigmoidal maturation model.

During the PopPK model-building process, successful minimization, diagnostic plots, plausibility, and the precision of parameter estimates, as well as OFV and shrinkage estimates, were used to assess model appropriateness. The diagnostic plots generated included individual predictions (IPREDs) and population predictions (PREDs) versus observations, conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus PREDs and time, individual subject plots, and a standardized visual predictive check (SVPC) (33). In the SVPC, the final model was used to generate 1,000 Monte Carlo simulation replicates per time point of solithromycin exposure. Simulated results were compared at the participant level with those observed in the study by calculating and plotting the percentile of each observed concentration in relation to its 1,000 simulated observations derived from the final model. The dosing and covariate values used to generate the simulations in the SVPC were the same as those used in the study population. The number of observed concentrations outside the 90% prediction interval was calculated. Parameter precision for the final PopPK model was evaluated using nonparametric bootstrapping (1,000 replicates) to generate the 95% confidence intervals for parameter estimates.

The cumulative AUC0–t was calculated using the software NONMEM by integrating the amounts in a dummy compartment and according to equation 11 (34). The cumulative AUC0–t represents the area under the solithromycin concentration-versus-time curve from 0 h until the time of individual lab value (AST, ALT, or total bilirubin) measurement. Only lab values obtained at >24 h after the first dose were plotted against cumulative AUC0–t estimates.

| (11) |

where Cp is the solithromycin plasma concentration and t is time.

Dosing simulations.

A data set of virtual subjects from 0 to <2 years, 2 to <6 years, 6 to <12 years, and 12 to 17 years of age was generated using the software PK-Sim (version 7.1; Bayer Technology Services, Leverkusen, Germany). One thousand virtual subjects were included for each age group-formulation cohort. Weight for age was assigned according to the distributions from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database in PK-Sim software. Using the final model parameters (including the estimated covariance between IIV terms), simulations were performed to identify pediatric dosing for i.v. and oral (suspension and capsules) administration that matches the solithromycin AUC0–24 and Cmax values observed in the phase 3 adult program. Simulated AUC0–24 and Cmax values on day 1 and day 5 were determined by performing a noncompartmental analysis of the simulated solithromycin concentration data in Phoenix WinNonlin (version 6.3; Certara, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Safety evaluation.

An independent data-monitoring committee assessed the overall study status and safety of subjects at intervals outlined in the charter. Adverse events, laboratory values, and vital signs were collected throughout the study. All subjects who received at least 1 dose of study drug were included in the safety analysis. Safety analyses included summaries of TEAEs, descriptive statistics of laboratory values and vital sign parameters, and frequency distributions of abnormal physical examinations.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was sponsored by the U.S. Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (HHSO100201300009C), which has a contract with Melinta Therapeutics, Inc., to perform the study. Daniel Gonzalez receives support for research from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD083465).

Participants from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority included James King, Claiborne Hughes, and Shar'Ron DeDreu. Participants from Melinta Therapeutics, Inc., Chapel Hill, NC, USA, included Brian Jamieson, Robert Hernandez, David Oldach, and Melissa Allaband. Participants from the Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC, USA, included Adam Silverstein (statistician), Felix Boakye-Agyeman (pharmacokineticist), Danielle Sutton (data management), Elizabeth VanDyne (safety), Carrie Elliott (lead clinical research associate), Theresa Jasion (project leader), and Christoph Hornik. The following participants were from the indicated clinical trial sites: Laura P. James (principal investigator [PI]) and Carol Pierce (study coordinator [SC]), Arkansas Children's Hospital Research Institute, Little Rock, AR, USA; Ram Yogev (PI) and Laura Fearn (SC), Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, IL, USA; Amira Al-Uzri (PI) and Kira Clark (SC), Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, USA; Miroslava Boshevae (PI), Medical University, Plovdiv, Bulgaria; Felice C. Adler-Shohet (PI) and Stephanie Osborne (SC), CHOC Children's, Orange, CA, USA; Susan R. Mendley (PI) and Donna Cannonier (SC), University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA; Munib Daudjee (PI) and Jessica Orsak (SC), Mercury Clinical Research, Houston, TX, USA; John S. Bradley (PI) and Sara Hingtgen (SC), Rady Children's Hospital—San Diego and the University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA; Claudia Espinosa (PI) and Andrew Michael (SC), Kosair Children's Hospital, Louisville, KY, USA; Eva Tsonkovak (PI), Multiprofile Hospital for Active Treatment, Ruse, Bulgaria; Kathryn Moffett (PI) and Tammy Carrington (SC), West Virginia University Hospital, Morgantown, WV, USA; Lucila Marquez (PI) and Farida Lalani (SC), Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, USA; Kari A. Simonsen (PI) and Kym Abraham (SC), University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA; Stefan Stoilov (PI), University Multiprofile Hospital for Active Treatment and Emergency Medicine “N. I. Pirogov,” Sofia, Bulgaria; Barry Bloom (PI) and Paula Delmore (SC), Wesley Medical Center, Wichita, KS, USA; John Vanchiere (PI) and Lisa Latiolais (SC), Louisiana State University Medical Center, New Orleans, LA, USA; Joshua Wolf (PI) and Kim Allison (SC), St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN, USA; Nathan Price (PI) and Gretchen Cress (SC), University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA, USA; Rachel Orscheln (PI) and Susan Jones (SC), Saint Louis Children's Hospital, St. Louis, MO, USA; and Water Dehority (PI) and Christina Batson (SC), University of New Mexico, Department of Pediatrics, Albuquerque, NM, USA.

D. Gonzalez and M. Cohen-Wolkowiez wrote the manuscript; F. Boakye-Agyeman, D. Gonzalez, and M. Cohen-Wolkowiez analyzed the data; D. Gonzalez and M. Cohen-Wolkowiez designed the research; D. Gonzalez, L. P. James, A. Al-Uzri, M. Bosheva, F. C. Adler-Shohet, S. R. Mendley, J. S. Bradley, C. Espinosa, E. Tsonkova, K. Moffett, L. Marquez, K. A. Simonsen, S. Stoilov, F. Boakye-Agyeman, T. Jasion, C. P. Hornik, R. Hernandez, D. K. Benjamin, Jr., and M. Cohen-Wolkowiez performed the research.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00692-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donald BJ, Surani S, Deol HS, Mbadugha U, Udeani G. 2017. Spotlight on solithromycin in the treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia: design, development, and potential place in therapy. Drug Des Dev Ther 11:3559–3566. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S119545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez D, Palazzi DL, Bhattacharya-Mithal L, Al-Uzri A, James LP, Bradley J, Neu N, Jasion T, Hornik CP, Smith PB, Benjamin DK, Keedy K, Fernandes P, Cohen-Wolkowiez M. 2016. Solithromycin pharmacokinetics in plasma and dried blood spots and safety in adolescents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:2572–2576. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02561-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llano-Sotelo B, Dunkle J, Klepacki D, Zhang W, Fernandes P, Cate JHD, Mankin AS. 2010. Binding and action of CEM-101, a new fluoroketolide antibiotic that inhibits protein synthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:4961–4970. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00860-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Putnam SD, Sader HS, Farrell DJ, Biedenbach DJ, Castanheira M. 2011. Antimicrobial characterisation of solithromycin (CEM-101), a novel fluoroketolide: activity against staphylococci and enterococci. Int J Antimicrob Agents 37:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woosley LN, Castanheira M, Jones RN. 2010. CEM-101 activity against gram-positive organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2182–2187. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01662-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodgers W, Frazier AD, Champney WS. 2013. Solithromycin inhibition of protein synthesis and ribosome biogenesis in Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1632–1637. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02316-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallegol J, Fernandes P, Melano RG, Guyard C. 2014. Antimicrobial activity of solithromycin against clinical isolates of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:909–915. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01639-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrell DJ, Mendes RE, Jones RN. 2015. Antimicrobial activity of solithromycin against serotyped macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates collected from U.S. medical centers in 2012. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:2432–2434. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04568-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salerno SN, Edginton A, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Hornik CP, Watt KM, Jamieson BD, Gonzalez D. 2017. Development of an adult physiologically based pharmacokinetic model of solithromycin in plasma and epithelial lining fluid. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 6:814–822. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira D, Degenhardt T, Fernandes P. 2010. Comparison of CEM-101 metabolism in mice, rats, monkeys and humans, abstr A-687. Abstr 50th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, Boston, MA. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okusanya OO, Bhavnani SM, Forrest A, Bulik CC, Jamieson B, Oldach D, Fernandes P, Ambrose PG. 2012. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic target attainment analysis for solithromycin to support intravenous dose selection in patients with community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, abstr A-1269. Abstr 52nd Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, San Francisco, CA. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okusanya ÓO, Bhavnani SM, Forrest A, Fernandes P, Ambrose PG. 2010. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic target attainment analysis supporting solithromycin (CEM-101) phase 2 dose selection, abstr A1-692. Abstr 50th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, Boston, MA. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrera CM, Mykietiuk A, Metev H, Nitu MF, Karimjee N, Doreski PA, Mitha I, Tanaseanu CM, Molina JMD, Antonovsky Y, Van Rensburg DJ, Rowe BH, Flores-Figueroa J, Rewerska B, Clark K, Keedy K, Sheets A, Scott D, Horwith G, Das AF, Jamieson B, Fernandes P, Oldach D, SOLITAIRE-ORAL Pneumonia Team. 2016. Efficacy and safety of oral solithromycin versus oral moxifloxacin for treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia: a global, double-blind, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled, non-inferiority trial (SOLITAIRE-ORAL). Lancet Infect Dis 16:421–430. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.File TM, Rewerska B, Vucinic-Mihailovic V, Gonong JRV, Das AF, Keedy K, Taylor D, Sheets A, Fernandes P, Oldach D, Jamieson BD. 2016. SOLITAIRE-IV: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter study comparing the efficacy and safety of intravenous-to-oral solithromycin to intravenous-to-oral moxifloxacin for treatment of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 63:1007–1016. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu K, Cohen EEW, House LK, Ramírez J, Zhang W, Ratain MJ, Bies RR. 2012. Nonlinear population pharmacokinetics of sirolimus in patients with advanced cancer. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 1:e17. doi: 10.1038/psp.2012.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okusanya ÓO, Forrest A, Bhavani S, Rodvold K, Gotfried M, Fernandes P, Clark K, Still J, Ambrose P. 2010. Population pharmacokinetics of solithromycin (CEM-101) using data from the plasma and epithelial lining fluid of healthy subjects, abstr A1-691. Abstr 50th Intersci Conf Antimicrob Agents Chemother, Boston, MA. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holford N, Heo Y, Anderson B. 2013. A pharmacokinetic standard for babies and adults. J Pharm Sci 102:2941–2952. doi: 10.1002/jps.23574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emoto C, Fukuda T, Mizuno T, Schniedewind B, Christians U, Adams DM, Vinks AA. 2016. Characterizing the developmental trajectory of sirolimus clearance in neonates and infants. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 5:411–417. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urien S, Firtion G, Anderson ST, Hirt D, Solas C, Peytavin G, Faye A, Thuret I, Leprevost M, Giraud C, Lyall H, Khoo S, Blanche S, Tréluyer JM. 2011. Lopinavir/ritonavir population pharmacokinetics in neonates and infants. Br J Clin Pharmacol 71:956–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03926.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chalkiadis GA, Anderson BJ. 2006. Age and size are the major covariates for prediction of levobupivacaine clearance in children. Paediatr Anaesth 16:275–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens J, Hines R, Gu C, Koukouritaki S, Manro J, Tandler P, Zaya M. 2003. Developmental expression of the major human hepatic CYP3A enzymes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 307:573–582. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.054841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson TN, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Tucker GT. 2006. Prediction of the clearance of eleven drugs and associated variability in neonates, infants and children. Clin Pharmacokinet 45:931–956. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200645090-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens RC, Reed MD, Shenep JL, Baker DK, Foulds G, Luke DR, Blumer JL, Rodman JH. 1997. Pharmacokinetics of azithromycin after single- and multiple-doses in children. Pharmacotherapy 17:874–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi J, Pfister M, Jenkins SG, Chapel S, Barrett JS, Port RE, Howard D. 2005. Pharmacodynamic analysis of the microbiological efficacy of telithromycin in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Pharmacokinet 44:317–329. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sampson MR, Dumitrescu TP, Brouwer KLR, Schmith VD. 2014. Population pharmacokinetics of azithromycin in whole blood, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and polymorphonuclear cells in healthy adults. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol 3:e103. doi: 10.1038/psp.2013.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beal SL. 2001. Ways to fit a PK model with some data below the quantification limit. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 28:481–504. doi: 10.1023/A:1012299115260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keizer RJ, van Benten M, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM, Huitema ADR. 2011. Piraña and PCluster: a modeling environment and cluster infrastructure for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 101:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindbom L, Pihlgren P, Jonsson EN, Jonsson N. 2005. PsN-Toolkit—a collection of computer intensive statistical methods for non-linear mixed effect modeling using NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 79:241–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarkar D. 2008. Lattice: multivariate data visualization with R, 1st ed Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wickham H. 2016. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis, 2nd ed Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO. 1999. Xpose—an S-PLUS based population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model building aid for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 58:51–64. doi: 10.1016/S0169-2607(98)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trame MN, Bergstrand M, Karlsson MO, Boos J, Hempel G. 2011. Population pharmacokinetics of busulfan in children: increased evidence for body surface area and allometric body weight dosing of busulfan in children. Clin Cancer Res 17:6867–6877. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang DD, Zhang S. 2012. Standardized visual predictive check versus visual predictive check for model evaluation. J Clin Pharmacol 52:39–54. doi: 10.1177/0091270010390040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cella M, Zhao W, Jacqz-Aigrain E, Burger D, Danhof M, Della Pasqua O. 2011. Paediatric drug development: are population models predictive of pharmacokinetics across paediatric populations? J Clin Pharmacol 72:454–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.