Abstract

Cyclooxygenase inhibitors were developed in the quest of enhanced analgesic efficacy devoid of gastric side effects. High usage of etoricoxib by prescription as well as self-administered routes has led to increasing reports of side effects and adverse reactions including dermatologic reactions in 0.1%–0.3% of cases. The present report enumerates a case of toxic epidermal necrolysis induced by etoricoxib.

Keywords: Adverse effects, algorithm of drug causality for epidermal necrolysis, etoricoxib, SCORTEN score, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Introduction

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a potentially fatal skin disorder whose hallmark is erythema, necrosis, and bullous detachment of the epidermis and mucosal membranes with exfoliation, which can be further complicated by sepsis and/or death. The involvement of mucous membrane may lead to complications such as gastrointestinal hemorrhage, respiratory failure, ocular, and genitourinary abnormalities. Drug reactions have been reported to cause 80%–95% of TEN cases. Drugs mostly implicated in TEN are antibiotics (sulfonamides [sulfamethoxazole, sulfadiazine, and sulfapyridine]; beta-lactams [cephalosporins, penicillins, and carbapenems]), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), allopurinol, antimetabolites like methotrexate, antiretroviral drugs like nevirapine, corticosteroids, anxiolytics like chlormezanone, anticonvulsants such as phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproic acid. The pathogenesis of TEN mainly alludes to immunologic reactions, reactive drug metabolites, and genetic aspects.[1]

Etoricoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitor, is claimed to have greater gastrointestinal tolerability profile compared to conventional nonselective nonsteroidal anti-NSAID. It is used in various chronic inflammatory conditions such as osteoarthritis, gouty arthritis, and also in instances of acute pain. Postmarketing surveillance and some case reports revealed its association with severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions (ADRs) such as Stevens–Johnson Syndrome (SJS), TEN, Erythema multiforme, and others.[2,3,4,5] However, published literature on severe cutaneous ADR or death following etoricoxib administration is scarce. In this report, we are presenting a case of fatal outcome following etoricoxib-induced TEN.

Case Report

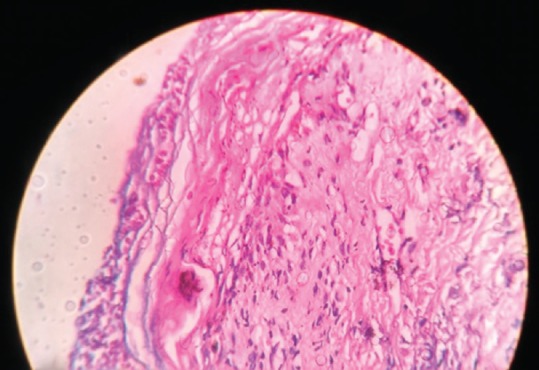

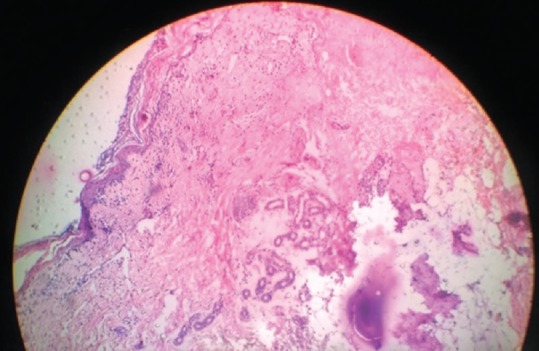

A 23-year-old female presented to a general practitioner in a private clinic for ankle sprain. She was prescribed etoricoxib 90 mg twice daily. After 5 days of initiation of the analgesic, she developed maculopapular, erythematous rash along with itching. Despite immediate discontinuation of all medications, her symptoms turned more severe with the formation of blisters, ulceration, and pigmentation involving skin and mucosa of the almost whole body [Figures 1–3]. She was admitted to a tertiary care hospital, diagnosed as TEN. Nikolsky sign was clearly elicited, and the SCORTEN score was determined [Table 1].[6] On histopathological examination of the involved area, it showed epidermal necrosis with formation of subepidermal bullae and extravasation of erythrocytes. There is prominent dermal lymphocytic infiltration with the presence of necrosis of hair follicles [Figures 4 and 5].

Figure 1.

Oral mucosal ulceration and pigmentation involving face and neck

Figure 3.

Maculopapular rash, hyperpigmentation, blisters, and bullae involving whole of the back

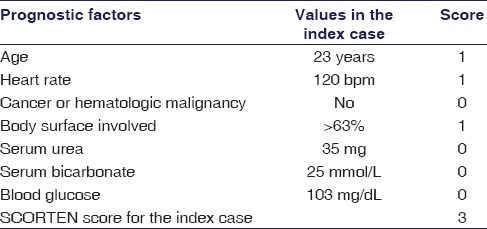

Table 1.

Severity of illness assessed by using the SCORTEN criteria

Figure 4.

Histopathological section showing extravasation of erythrocytes with dermal lymphocytic infiltration

Figure 5.

Histopathological sections showing epidermal necrosis; necrosis of hair follicles, and formation of subepidermal bullae

Figure 2.

Maculopapular rash, bullae and hyperpigmentation involving arm and forearm

On hospitalization, she was managed with IV fluids, corticosteroids, antibiotics, emollients, and later tried in vain with cyclosporine. Despite meticulous supportive care and withdrawal of all suspected drugs, patient's condition worsened, and she, unfortunately, collapsed after 5 days of hospitalization.

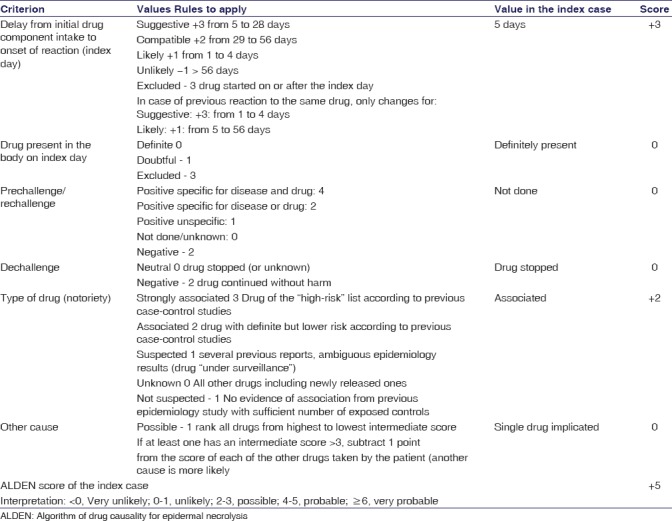

The causality assessment as per the Naranjo algorithm[7] and WHO-UMC criteria[8] revealed the ADR to be “probable” (Naranjo score 8). The assessment of causality by using the algorithm of drug causality for epidermal necrolysis[9] [Table 2] was also used. The event was assessed to be nonpreventable under Schumock-Thornton scale.[10] The case was reported under the National Pharmacovigilance Programme (IN-IPC-2016-07793).

Table 2.

Assessment of causality by using the algorithm of drug causality for epidermal necrolysis

Discussion

ADRs become a matter of concern for being one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients. Reports from various studies confer that approximately 8% of cases among all hospitalizations are due to ADRs.[11] With widespread use of pain medications worldwide, effective vigilance, and proper patient counseling on various adverse effects of it is thus advised. NSAIDs are mostly COX inhibitors which are some of the most commonly used analgesic medicine. However, their adverse effects profile restricts the long-term use. As the constitutively active enzyme COX-1 is widely expressed and has housekeeping function, therefore its inhibition brings about most of the adverse effects. Whereas COX-2 inhibition is more selectively associated with analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities. Etoricoxib is such a COX-2 inhibitor having 30-fold selectivity. It is indicated for chronic inflammatory conditions such as osteoarthritis, chronic low backache, gouty arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and also in acute inflammatory conditions. High usage of etoricoxib by prescription as well as self-administered routes has led to increase in reports of side effects and adverse reactions including dermatologic reactions in 0.1%–0.3% of cases.[12] The present report enumerates a case of TEN induced by etoricoxib.

The international classification of SJS/TEN is based on the body surface area (BSA) involvement. By definitions SJS involves < 10% of BSA; TEN involves >30%; and overlap syndrome with involvement of 10%–30%. Common causes of death include septic shock, hypovolemic shock, acute renal failure, fulminant hepatitis, and multi-organ involvement.[13]

The clinical spectrum of dermatological adverse reactions ranges from mild rash to TEN/SJS, making the diagnosis a tedious affair. TEN is a type of ADR which is associated with high morbidity and mortality. The exact pathogenesis is complex as there is a strong predilection of it being autoimmune mediated which indicates there is involvement of two phases, namely the initiation phase and the amplification phase. During the initiation phase, drug metabolites stimulate CD95 ligand (Fas ligand) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) systems resulting in apoptosis. During the amplification stage, there is activation of inflammatory cells such as TNF-α and interleukin-2 (IL-2) which are chemotactic cytokines, these help in the recruitment of CD41 T lymphocyte and CD81 cells in the dermis and epidermis, respectively. TNF-α and IL-2 also act as messengers which stimulates the release of chemotactic factors; and finally, there is the recruitment of natural killer cells and macrophages into the epidermis. All these factors lead to massive destruction of epidermis which makes the diagnosis certain. On histopathological examination, the present case showed extensive keratinocyte apoptosis and necrosis. This is the pathogenesis of widespread epidermal detachment that is observed in most cases of TEN lesions.[14]

Owing to its high mortality, extra caution should be ensured in the management of these life-threatening reactions. Prime requisites for the management of these reactions include early identification, prompt intervention with effective care and support.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gurung A, Jaju JB, Solunke R, Pawar GR, Dharmadhikari SC, Ubale VM. Carbamazepine induced toxic epidermal necrolysis in a patient of seizure disorder. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2016;5:531–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Information on Arcoxia. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 31]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov.tw/MLMS/ShowFile.aspx?LicId=02023981&Seq=017&Type=9 .

- 3.Kameshwari JS, Devde R. A case report on toxic epidermal necrolysis with etoricoxib. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47:221–3. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.153436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreft B, Wohlrab J, Bramsiepe I, Eismann R, Winkler M, Marsch WC, et al. Etoricoxib-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis: Successful treatment with infliximab. J Dermatol. 2010;37:904–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rachana PR, Anuradha HV, Mounika R. Stevens Johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis overlap secondary to interaction between methotrexate and etoricoxib: A case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:FD01–3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14221.6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastuji-Garin S, Fouchard N, Bertocchi M, Roujeau JC, Revuz J, Wolkenstein P, et al. SCORTEN: A severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:149–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The use of the WHO-UMC System for Standardised Case Causality Assessment. [Last accessed on 2016 Dec 31]. Available from: http://www.WHO-UMC.org/graphics/4409.pdf .

- 9.Sassolas B, Haddad C, Mockenhaupt M, Dunant A, Liss Y, Bork K, et al. ALDEN, an algorithm for assessment of drug causality in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Comparison with case-control analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:60–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schumock GT, Thornton JP. Focusing on the preventability of adverse drug reactions. Hosp Pharm. 1992;27:538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouvy JC, De Bruin ML, Koopmanschap MA. Epidemiology of adverse drug reactions in Europe: A review of recent observational studies. Drug Saf. 2015;38:437–53. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0281-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Settipane GA. Aspirin and allergic diseases: A review. Am J Med. 1983;74:102–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mockenhaupt M. The current understanding of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011;7:803–13. doi: 10.1586/eci.11.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frisch PO, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Erythemamultiforme, Stevens Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. pp. 543–57. [Google Scholar]