Abstract

Culturomics has permitted discovery of hundreds of new bacterial species isolated from the human microbiome. Profiles generated by using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry have been added to the mass spectrometer database used in clinical microbiology laboratories. We retrospectively collected raw data from MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry used routinely in our laboratory in Marseille, France, during January 2012–March 2018 and analyzed 16S rDNA sequencing results from misidentified strains. During the study period, 744 species were identified from clinical specimens, of which 21 were species first isolated from culturomics. This collection involved 105 clinical specimens, accounting for 98 patients. In 64 cases, isolation of the bacteria was considered clinically relevant. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was able to identify the species in 95.2% of the 105 specimens. While contributing to the extension of the bacterial repertoire associated with humans, culturomics studies also enlarge the spectrum of prokaryotes involved in infectious diseases.

Keywords: culturomics, MALDI-TOF MS, new species, clinical microbiology, culture, microbiology, bacteria, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry

The diagnosis of bacterial diseases in clinical microbiology has relied on phenotypic identification, based on the bacterial repertoire known to be associated with humans. This mode of identification, which is, in fact, recognition of previously described microorganisms, does not allow for the identification of new bacteria. Recently, the systematic use of universal 16S rDNA gene sequencing of cultivated bacteria that presented an atypical phenotypical profile paved the way for identifying rare, fastidious, and new microorganisms (1,2). However, this method implies redefining specific phenotypical characteristics, which sometimes cannot be done because of the limited number of available biochemical tests. More recently, the revolution provided by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry identification permits comparison of a protein spectrum obtained from a colony with a database, which can be permanently incremented with newly identified bacteria (3,4). The use of a cutoff identification score, with values in the range of 1.7–2, enables correct identification of the isolate. However, when MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry recognizes bacteria never previously associated with humans, it is reasonable to carry out confirmation by sequencing the 16S rDNA gene. The main advantage of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry compared with sequencing methods is that it is extremely fast and cost-effective (3,4). Indeed, the cost involves mainly the cost of the machine; the individual cost per test is insignificant. Thus, the ease in testing bacterial colonies led us to establish the repertoire of commensal bacteria of the human microbiota in the laboratory at IHU Méditerranée Infection in Marseille, France, by using a high-throughput culture and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identification. Sequencing of the 16S rDNA gene enables identification of atypical bacteria with definition of new bacterial species, whose genomes are then sequenced. This approach, called culturomics (5,6), has made possible the addition of 672 bacteria to the known repertoire of the bacteria already isolated from the human mucosa. Other teams, in parallel, have used similar approaches (7,8).

The usefulness of culturomics in increasing knowledge of the repertoire of cultivable bacteria from human mucous membranes appears clear for microbiota studies. However, the benefit of this process in clinical microbiology is prone to controversy. We speculated that commensal bacteria found in humans may be involved in opportunistic infections. In our experience, the creation of new spectra enabled us to increment our MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry database used for clinical microbiology, thus enabling recognition of bacterial species first isolated as a part of culturomics studies and improving the accuracy of diagnosis of infectious diseases involving bacteria.

Materials and Methods

Settings

All data included in this study were obtained from the routine microbiology laboratory at IHU Méditerranée Infection, which receives a mean annual number of 350,400 samples from the 4 Marseille university hospitals (Timone, Conception, North, and Sainte-Marguerite hospitals), which contain a total of 3,700 beds. Retrospective data were collected for January 2012–March 2018.

Routine Bacteriological Practices

We analyzed samples according to standard microbiological procedures, as previously described, depending on the specimen (9–12). This process included systematic inoculation onto Columbia agar with 5% sheep blood (BioMérieux, Craponne, France), chocolate agar (BioMérieux) (excluding urine and fecal samples), and specific media such as colistin-nalidixic agar or MacConkey agar (both BioMérieux) for specimens potentially contaminated by resident flora. Blood cultures were incubated into a Bactec device (Becton Dickinson, Le Pont de Claix, France) and analyzed as previously described (9).

Specific Cultures

We plated fecal specimens taken following a regional outbreak of Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile 027 during May 2013–March 2018 (13), in which toxin detection was positive using GeneXpert C. difficile PCR (Cepheid, Paris, France) after ethanol treatment (14), to obtain C. difficile isolates. We also investigated possible multidrug-resistant bacteria carriage by plating on chromID MRSA agar for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, chromID CARBA SMART medium (BioMérieux) for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE), and Drigalski/MacConkey agar (BioMérieux) for third-generation, cephalosporin-resistant, gram-negative bacteria.

Identification of Colonies

We performed bacterial identification on colonies using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, as previously described (3,4). We considered identification to be correct when the identification score was >1.9 and when the same single species was recognized. When identification did not meet these criteria, we performed proteic extraction using formic acid and acetonitrile (15). If identification was still incorrect following the proteic extraction protocol, we performed 16S rDNA sequencing systematically, as previously described (16), in 3 situations: when the identification score was <1.9 despite proteic extraction, when multiple different species were recognized with a correct identification score, and when a bacterium was isolated for the first time in the clinical microbiology laboratory.

Culturomics Studies

In brief, culturomics consists of the multiplication of culture conditions applied to human specimens to increase the repertoire of the human microbiome. The pioneering study used 212 conditions (5); this number was reduced to 70 in 2012 (17,18) and then to 18 in 2014 (6). In addition, several specific conditions were designed for archaea, microcolonies, proteobacteria, and microaerophilic and halophilic bacteria. Most specimens used were fecal samples. However, respiratory, vaginal, and urine samples have been analyzed recently in the context of culturomics studies. Identification has also been performed using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Colonies were considered correctly identified when 2 colonies exhibited an identification score >1.9. If identification scores were not correct after 3 attempts, sequencing of the 16S rDNA gene was performed (16). If there was <98.7% similarity with the closest neighbor, the bacterial isolate was considered to be a new species (19).

Updating the MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry Database

The database used for routine bacterial identification is updated through 3 sources: updates from the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry manufacturer, updates from culturomics studies, and routine laboratory results. Updates from culturomics studies and routine laboratory results are based on 16S rDNA sequencing results.

Analysis of Data from MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry Used in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory

We retrospectively collected raw data from MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry used in the microbiology laboratory involving identifications performed during January 2012–March 2018, which are saved monthly. Data were deduced from the samples. These data do not consider the clinical relevance of the identified microorganism, the final result, or multiple attempts to identify the colony using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Results

Bacterial Identification in Clinical Microbiology Laboratory

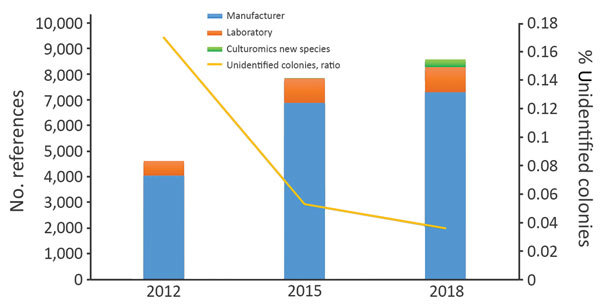

During January 2012–March 2018, the clinical microbiology laboratory performed 351,937 nondereplicated bacterial identifications using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Of these, 28,391 (8.1%) were unidentified or misidentified. When we looked at the yearly ratio of unidentified bacteria, we noticed that it fell from 17.7% in 2012 to 3.6% in 2018 (Figure). Overall, we identified 744 unique bacterial species correctly using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry.

Figure.

Annual ratio of unidentified bacteria and evolution of the number of spectral references available in the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry database in a clinical laboratory in Marseille, France.

Contribution to MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry Database Updates

During the study period, we added 4,539 references to our database. Updates from the manufacturer comprised 3,255 references, whereas 983 references came from routine laboratory results. In addition, 306 (23.4%) updates were from new bacterial species discovered as a part of culturomics studies. Overall, references from the manufacturer represented 87% of the total database, routine laboratory results represented 8%, and new culturomics species represented 5% (Figure).

Routine Identification of Species Isolated as Part of Culturomics Studies

Among the 351,937 bacterial identifications performed routinely during the study period, we identified species first isolated from culturomics studies in 105 clinical specimens, accounting for 98 patients. This collection represents a total of 21 species, accounting for 2.8% (21/744) of the overall microbiology laboratory bacterial diversity (Table 1).

Table 1. Main features of the bacteria discovered as part of culturomics studies identified in a clinical microbiology laboratory*.

| Species | Culturomics study | CSUR no. | Strain | GenBank accession no. | Date of spectrum implementation | No. cases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinomyces bouchesdurhonensis | Gut microbiota (storied samples) | P2825 | Marseille-P2825T | LT576385 | 2017 Apr | 3 | Unpub. data |

| Actinomyces ihuae | Gut microbiota (HIV) | P2006 | SD1 | LN866997 | 2015 Jul | 17 | (6,20) |

| Actinomyces marseillensis | Respiratory microbiota | P2818 | Marseille-P2818T | LT576400 | Not added | 1 | (21) |

| Alistipes jeddahensis | Gut microbiota | P1209 | AL1 | LK021116 | 2015 Oct | 4 | (6,22) |

| Anaerosalibacter massiliensis | Gut microbiota (Polynesia) | P762 | ND1 | HG315673 | 2013 Apr | 1 | (6,23) |

| Bacteroides timonensis | Gut microbiota (anorexia nervosa) | P194 | AP1 | JX041639 | 2016 Apr | 2 | (6,24) |

| Butyricimonas phocaeensis | Gut microbiota (obese) | P2478 | AT9 | LN881597 | 2015 Nov | 1 | (6,25) |

| Clostridium culturomicsense | Gut microbiota (Saudian obese) | P1184 | CL6 | LK021117 | 2014 Sep | 1 | (6,26) |

| Clostridium jeddahtimonense | Gut microbiota (obese) | P1230 | CL2 | LK021118 | 2014 Aug | 7 | (6) |

| Clostridium massilioamazoniense | Gut microbiota (Polynesia) | P1360 | ND2 | HG315672 | 2013 May | 1 | (6) |

| Clostridium saudii | Gut microbiota (Saudian obese) | P697 | JCC | HG726039 | 2014 Aug | 11 | (6,27) |

| Corynebacterium ihuae | Gut microbiota (antimicrobials) | P892 | GD6 | JX424768 | 2013 May | 3 | (6,28) |

| Corynebacterium lascolaense | Urinary microbiota | P2174 | MC3 | LN881612 | 2013 Sep | 6 | (6) |

| Corynebacterium phoceense | Urinary microbiota | P1905 | MC1 | LN849777 | 2015 May | 12 | (6,29) |

| Gabonia massiliensis | Gut microbiota | P1910 | GM3 | LN849789 | 2017 Apr | 1 | (6,30) |

| Nosocomicoccus massiliensis | Gut microbiota (HIV) | P246 | NP2 | JX424771 | 2012 Feb | 1 | (6,31) |

| Peptoniphilus grossensis | Gut microbiota (obese) | P184 | ph5 | JN837491 | 2015 Nov | 18 | (6,32) |

| Polynesia massiliensis | Gut microbiota (Polynesia) | P1280 | MS3 | HF952920 | 2013 Mar | 1 | (6) |

| Prevotella ihuae | Gut microbiota (fresh feces) | P3385 | Marseille-P3385T | LT631517 | Not added | 1 | (33) |

| Pseudomonas massiliensis | Gut microbiota (Polynesia) | P1334 | CB1 | LK985396 | 2015 Apr | 5 | (6,34) |

| Varibaculum timonense | Gut microbiota (fresh feces) | P3369 | Marseille-P3369T | LT797538 | Not added | 1 | (33) |

*Accession numbers indicate nucleotide sequences. CSUR, Collection de Souches de l’Unité des Rickettsies (an international strain collection).

Among the 105 colonies identified as new species isolated as a part of culturomics studies, identification was correct for 100 (95.2%) using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Thus, 16S rDNA gene sequencing was required for 5 strains to achieve final identification. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was not able to provide a reliable identification for Varibaculum timonense, Prevotella ihuae, Actinomyces ihuae, and 2 Corynebacterium phoceense isolates. We confirmed identification of 9 supplementary strains, representing 5 species (Corynebacterium lascolaense, Actinomyces ihuae, Corynebacterium ihuae, Nosocomiicoccus massiliensis, and Pseudomonas massiliensis), using 16S rDNA gene sequencing (Tables 2,3). Overall, we sequenced 14 isolates, accounting for 8 species, for the 16S rDNA gene.

Table 2. Identification of bacterial pathogens by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, Marseille, France*.

| Species | MALDI-TOF identification (score) | Specimen | Duplicates per patient?† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actinomyces bouchesdurhonensis | Actinomyces bouchesdurhonensis (1.85) | Pharynx swab | No |

| A. bouchesdurhonensis | A. bouchesdurhonensis (1.9) | Abscess | No |

| Actinomyces ihuae | Actinomyces ihuae (1.97) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (1.9) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (2.5) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (1.92) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (2.5) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (1.73) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (2.23) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (2.2) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (2.1) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (2.1) | Bone | No |

| A. ihuae | A. ihuae (2.52) | Puncture fluid | No |

| A. ihuae‡ | A. ihuae (2.47) | Puncture fluid | No |

| A. ihuae‡ | Actinomyces spp. (1.65) | Biopsy | No |

| A. ihuae‡ | A. ihuae (2.32) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae‡ | A. ihuae (2.33) | Abscess | No |

| A. ihuae‡ | A. ihuae (1.95) | Puncture fluid | No |

| A. ihuae‡ | A. ihuae (2.07) | Abscess | No |

| Actinomyces marseillensis | Actinomyces marseillensis (NA) | Blood culture | No |

| Alistipes jeddahensis | Alistipes jeddahensis (1.97) | Abscess | No |

| Bacteroides timonensis | Bacteroides timonensis (1.95) | Blood culture | Yes |

| B. timonensis | B. timonensis (1.88) | Blood culture | Yes |

| B. timonensis | B. timonensis (1.96) | Blood culture | No |

| Corynebacterium ihuae‡ | Corynebacterium ihuae (2) | Blood culture | No |

| C. ihuae | C. ihuae (2.2) | Wound | No |

| C. ihuae | C. ihuae (1.8) | Blood culture | No |

| Corynebacterium lascolaense | Corynebacterium lascolaense (2.2) | Urine | No |

| C. lascolaense | C. lascolaense (2.3) | Pacemaker | No |

| C. lascolaense | C. lascolaense (2.1) | Urine | Yes |

| C. lascolaense | C. lascolaense (2.14) | Urine | Yes |

| C. lascolaense‡ | C. lascolaensis (2.2) | Urine | No |

| Corynebacterium phoceense | Corynebacterium phoceense (1.91) | Urine | No |

| C. phoceense | Corynebacterium spp. (2.3) | Unknown | No |

| C. phoceense | C. phoceense (2.6) | Blood culture | No |

| C. phoceense‡ | No reliable identification | Blood culture | No |

| Nosocomicoccus massiliensis‡ | Nosocomicoccus massiliensis (2.3) | Blood culture | No |

| Peptinophilus grossensis | Peptinophilus grossensis (2.1) | Abscess | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.18) | Biopsy | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (1.9) | Abscess | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.3) | Biopsy | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (1.9) | Biopsy | Yes |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.2) | Biopsy | Yes |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.18) | Biopsy | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2) | Material | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (1.78) | Abscess | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.1) | Abscess | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.15) | Abscess | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (1.9) | Puncture fluid | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.1) | Puncture fluid | Yes |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.3) | Puncture fluid | Yes |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.2) | Puncture fluid | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.1) | Abscess | Yes |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.1) | Abscess | Yes |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (1.9) | Puncture fluid | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.3) | Biopsy | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (2.31) | Biopsy | No |

| P. grossensis | P. grossensis (1.86) | Abscess | No |

| Polynesia massiliensis | Polynesia massiliensis (2.21) | Peritoneal fluid | No |

| Prevotella ihuae | No reliable identification | Abscess | No |

| Pseudomonas massiliensis | Pseudomonas massiliensis (2.5) | Blood culture | No |

| Pseudomonas massiliensis | Pseudomonas massiliensis (2) | Blood culture | No |

| Pseudomonas massiliensis‡ | Pseudomonas massiliensis (1.9) | Blood culture | No |

|

Varibaculum timonense

|

No reliable identification |

Abscess |

No |

| *MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight; NA, not available. †Replicated isolates in different specimens from the same patient. ‡Strains for which 16S rDNA sequencing was performed. | |||

Table 3. Identification of bacteria discovered as a part of culturomics studies in the clinical microbiology laboratory as commensals, Marseille, France*.

| Species | MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identification (score) | Specimen | Duplicates per patient?† | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinomyces bouchesdurhonensis | A. bouchesdurhonensis (2) | Larynx biopsy | No | Polymicrobial |

| Alistipes jeddahensis | Alistipes jeddahensis (2.38) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking Salmonella spp. |

| A. jeddahensis | A. jeddahensis (2.45) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking Salmonella spp. |

| A. jeddahensis | A. jeddahensis (2.5) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking Salmonella spp. |

| Anaerosalibacter massiliensis | Anaerosalibacter massiliensis (1.78) | Rectal swab | No | Seeking MDR bacteria |

| Butyricimonas phocaeensis | Butyricimonas phoaceensis (2.36) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| Clostridium culturomicsense | Clostridium culturomicsense (2) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| Clostridium jeddahtimonense | Clostridium jeddahtimonense (2.1) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. jeddahtimonense | C. jeddahtimonense (2.3) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. jeddahtimonense | C. jeddahtimonense (2.4) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. jeddahtimonense | C. jeddahtimonense (2.1) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. jeddahtimonense | C. jeddahtimonense (2.2) | Liquid feces | Yes | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. jeddahtimonense | C. jeddahtimonense (1.72) | Liquid feces | Yes | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. jeddahtimonense | C. jeddahtimonense (2.3) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. jeddahtimonense | C. jeddahtimonense (2.1) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| Clostridium massilioamazoniense | Clostridium massilioamazoniense (1.7) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| Clostridium saudii | Clostridium saudii (2.5) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (1.74) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (2.5) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (1.94) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (2.18) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (1.77) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (1.93) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (2.1) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (1.9) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (2.47) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| C. saudii | C. saudii (1.83) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking toxigenic CD |

| Corynebacterium lascolaense | Corynebacterium lascolaense (1.85) | Intrauterine device | No | Not considered |

| C. lascolaense | C. lascolaense (2.1) | Urine | No | Growth not significant |

| Corynebacterium phoceense | Corynebacterium phoceense (2.1) | Vagina | No | Not considered |

| C. phoceense | C. phoceense (1.9) | Vagina | No | Not considered |

| C. phoceense | C. phoceense (2.1) | Vagina | No | Not considered |

| C. phoceense | C. phoceense (2) | Vagina | No | Not considered |

| C. phoceense | C. phoceense (2.2) | Vagina | No | Not considered |

| C. phoceense | C. phoceense (2) | Vagina | No | Polymicrobial |

| C. phoceense | C. phoceense (2.2) | Vagina | No | Not considered |

| C. phoceense | C. phoceense (1.97) | Urine | No | Polymicrobial |

| Gabonia massiliensis | Gabonia massiliensis (2.3) | Liquid feces | No | Seeking MDR bacteria |

| Pseudomonas massiliensis | Pseudomonas massiliensis (2) | Skin swab | Yes | Seeking S. aureus carriage |

|

P. massiliensis

|

P. massiliensis (2.5) |

Skin swab |

Yes |

Seeking S. aureus carriage |

| *MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight. †Replicated isolates in different specimens from the same patient. | ||||

Species Potentially Relevant as Human Pathogens

Among the 105 isolates included in this work, 64 were isolated as potential pathogens, accounting for 14 different species. Most were anaerobes that were cultured from abscesses or punctures, often involved in cases of polymicrobial infections. Peptoniphilus grossensis (18 cases) and Actinomyces ihuae (17 cases) were the most commonly isolated bacteria (Table 1). These species were initially cultured from the human gut. Special attention was given to A. ihuae infections (Table 4), which were strongly associated with breast abscess or genital area infections. Also, 10 bacteremia-involved species were isolated as a part of culturomics studies. Bacteroides timonensis was thus isolated in 3 blood cultures from 2 patients, whereas Pseudomonas massiliensis was found in 3 bacteremia episodes. Corynebacterium phoceense and Corynebacterium ihuae were recovered from 2 bloodstream infection episodes, whereas Actinomyces marseillensis and Nosocomicoccus massiliensis were each isolated from 1 blood sample (from 2 different patients). B. timonensis, P. massiliensis, N. massiliensis, and C. ihuae were first cultured from the human gut, whereas A. marseillensis was first isolated from respiratory microbiota and C. phoceense was first isolated from urinary microbiota. Overall, species cultured as part of culturomics studies were found to be potential pathogens in 59 different patients (Table 2). The significance of the presence of P. massiliensis in a lens from a patient with keratitis was ultimately not interpreted.

Table 4. Characteristics of 17 persons with A. ihuae infection, Marseille, France, April 2015–March 2018*.

| Patient no. | Patient age, y/sex | Sampling site | Incubation time, h | Culture result | MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry score | 16S rRNA result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 24/F | Periareolar right breast | 48 | Polymicrobial | 2.54 | NA |

| 2 | 26/F | Umbilical collection | 48 | Pure | 2.5 | NA |

| 3 | 37/M | Periareolar left breast | 72 | Polymicrobial | 1.97 | NA |

| 4 | 33/F | Breast | 72 | Polymicrobial | 2.1 | NA |

| 5 | 77/F | Bone | 72 | Polymicrobial | 2.1 | NA |

| 6 | 22/M | Testicular collection | 96 | Pure | 1.95 | A. ihuae 99.70% |

| 7 | 56/M | Back | 48 | Pure | 2.32 | A. ihuae 99.70% |

| 8 | 55/F | Labia majora | 72 | Polymicrobial | 2.07 | A. ihuae 99.70% |

| 9 | 30/F | Labia majora | 72 | Pure | 2.47 | A. ihuae 99.70% |

| 10 | 26/F | Labia majora | 72 | Polymicrobial | 2.33 | A. ihuae 99.60% |

| 11 | 44/M | Leg ulcer | 48 | Polymicrobial | NA | A. ihuae 99.50% |

| 12 | 66/M | Cervical collection | 72 | Polymicrobial | 2.23 | NA |

| 13 | 49/M | Superinfected sebaceous cyst | 48 | Polymicrobial | 1.9 | NA |

| 14 | 18/F | Sacrococcygeal cyst | 96 | Pure | 2.45 | NA |

| 15 | 26/F | Labia majora | 72 | Polymicrobial | 2.2 | NA |

| 16 | 45/F | Breast abcess | 72 | Polymicrobial | 1.73 | NA |

| 17 | 44/M | Axillar abcess | 96 | Polymicrobial | 1.92 | NA |

| * MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight; NA, not available | ||||||

Species Isolated as Human Commensal Members

In this work, 40 isolates corresponding to 12 species discovered as a part of culturomics studies were isolated as belonging to the human flora. Of these, 22 were recovered when evaluating for toxigenic C. difficile, following a positive result with the GeneXpert C. difficile test. C. saudii was isolated in this context 11 times, followed by C. jeddahtimonense (8 times), C. culturomicsense, Butyricimonas phocaeensis, and Anaerosalibacter massiliensis (1 time each) (Table 3). These 5 species were first cultured from fecal specimens (Table 1).

In addition, Corynebacterium lascolaense was identified in 1 urine specimen, but in an insufficient quantity to be considered clinically relevant. Similarly, C. phoceense was recovered from 1 urine sample and from 7 vaginal swabs but was never reported to a physician in this context. These species were first cultured from urinary microbiota. Finally, Pseudomonas massiliensis, which was cultured from the human gut, was also recovered twice from skin swabs collected from the same physician after an epidemiologic investigation. Overall, species cultured for the first time as a part of culturomics studies were found as commensals in 38 different patients.

Discussion

This work constitutes the proof of concept that exploration of the repertoire of commensal bacteria enables identification of microorganisms involved in clinical microbiology. Indeed, the strategy of combining high-throughput culture techniques, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry identification, and 16S rDNA gene sequencing of misidentified isolates enabled us to add 306 spectral references for 292 different new bacterial species to our laboratory’s database. Thus, with culturomics, 21 new species were identified 105 times, in 98 patients. The results are robust; identification scores were all >1.9 with exclusion of multiple identifications. In addition, identification of 9 strains using 16S rDNA sequencing, accounting for 5 species, confirmed the initial recognition by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Table 2). These results strengthen our belief that identifying commensal microbes provides a valuable contribution to clinical microbiology, as revealed by the decrease in the number of unidentified colonies by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry over time (Figure).

As exemplified for A. ihuae infections (Table 4), these microorganisms, which were isolated mainly from the human gut, can probably be found frequently in polymicrobial cultures. Thus, the microbiologist may be tempted to abandon the final identification of a microorganism found in such a situation, concluding that the infection is polymicrobial.

The extension of the bacterial repertoire associated with humans will considerably increase the number of bacteria associated with human diseases. In this study alone, over a 5-year period, 2.8% (21/744) of the overall identified bacteria would not have been identified without incrementing the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry database with spectra obtained from culturomics studies.

On the whole, pathogenic microbes are also often found as commensals, as is currently well known for C. difficile, S. aureus, and S. pneumoniae (35–37). In our study, for example, Corynebacterium phoceense, Pseudomonas massiliensis, and C. lascolaense were found as both commensals and pathogens. This finding highlights the need for establishment of a repertoire of human microbes (38), which was recently estimated at 2,776 species, of which more than 10% were recovered by culturomics studies. Such a repertoire of prokaryotes associated with humans not only benefits microbiota studies, through notation of unknown sequences with new species genome sequencing, but also enables studying the role of these species in human infections (39). We estimate that, among the cases included here, the presence of species cultured as part of culturomics studies was potentially clinically relevant for 60 of them (61.2%). The online availability of the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry spectra obtained from these species discovered by culturomics (http://www.mediterranee-infection.com/article.php?laref=256&titre=urms-database) ensures their further identification by other laboratories.

Culturomics was initially designed to exhaustively identify commensals inhabiting human surfaces and thus can potentially lead in the future to personal medical interventions as a part of microbiome studies. However, the thinnest barrier between commensalism and pathogenicity, which should lead researchers to rethink Koch’s postulate (40), has rendered culturomics studies useful in the field of clinical microbiology despite a potential skepticism. We show herein that, while contributing to the extension of the bacterial repertoire associated with humans, culturomics studies also enlarge the spectrum of prokaryotes involved in infectious diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work has benefited from French state support, managed by the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche, including the Programme d’Investissement d’Avenir under the reference Méditerranée Infection 10-IAHU-03. This work was also supported by Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur and Fonds Européen de Développement Regional—Plateformes de Recherche et d'Innovation Mutualisées Méditerranée Infection (FEDER PRIMI).

Biography

Dr. Dubourg is an assistant professor of bacteriology at IHU Méditerranée Infection, Marseille, France. His primary research interest is human microbiome studies.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Dubourg G, Baron S, Cadoret F, Couderc C, Fournier P-E, Lagier J-C, et al. From culturomics to clinical microbiology and forward. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Sep [date cited]. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2409.170995

References

- 1.Drancourt M, Berger P, Raoult D. Systematic 16S rRNA gene sequencing of atypical clinical isolates identified 27 new bacterial species associated with humans. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2197–202. 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2197-2202.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drancourt M, Bollet C, Carlioz A, Martelin R, Gayral JP, Raoult D. 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis of a large collection of environmental and clinical unidentifiable bacterial isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3623–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark AE, Kaleta EJ, Arora A, Wolk DM. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry: a fundamental shift in the routine practice of clinical microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:547–603. 10.1128/CMR.00072-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seng P, Drancourt M, Gouriet F, La Scola B, Fournier PE, Rolain JM, et al. Ongoing revolution in bacteriology: routine identification of bacteria by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:543–51. 10.1086/600885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagier JC, Armougom F, Million M, Hugon P, Pagnier I, Robert C, et al. Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:1185–93. 10.1111/1469-0691.12023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lagier JC, Khelaifia S, Alou MT, Ndongo S, Dione N, Hugon P, et al. Culture of previously uncultured members of the human gut microbiota by culturomics. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16203. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman AL, Kallstrom G, Faith JJ, Reyes A, Moore A, Dantas G, et al. Extensive personal human gut microbiota culture collections characterized and manipulated in gnotobiotic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:6252–7. 10.1073/pnas.1102938108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Browne HP, Forster SC, Anonye BO, Kumar N, Neville BA, Stares MD, et al. Culturing of ‘unculturable’ human microbiota reveals novel taxa and extensive sporulation. Nature. 2016;533:543–6. 10.1038/nature17645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gouriet F, Million M, Henri M, Fournier PE, Raoult D. Lactobacillus rhamnosus bacteremia: an emerging clinical entity. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:2469–80. 10.1007/s10096-012-1599-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubourg G, Delord M, Gouriet F, Fournier PE, Drancourt M. Actinomyces gerencseriae hip prosthesis infection: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2015;9:223. 10.1186/s13256-015-0704-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy PY, Fournier PE, Fenollar F, Raoult D. Systematic PCR detection in culture-negative osteoarticular infections. Am J Med. 2013;126:1143.e25–33. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubourg G, Abat C, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Correlation between sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:994–6. 10.1128/JCM.02918-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassir N, Delarozière JC, Dubourg G, Delord M, Lagier JC, Brouqui P, et al. A regional outbreak of Clostridium difficile PCR-ribotype 027 infections in southeastern France from a single long-term care facility. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1337–41. 10.1017/ice.2016.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marler LM, Siders JA, Wolters LC, Pettigrew Y, Skitt BL, Allen SD. Comparison of five cultural procedures for isolation of Clostridium difficile from stools. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:514–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Khéchine A, Couderc C, Flaudrops C, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry identification of mycobacteria in routine clinical practice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24720. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morel AS, Dubourg G, Prudent E, Edouard S, Gouriet F, Casalta JP, et al. Complementarity between targeted real-time specific PCR and conventional broad-range 16S rDNA PCR in the syndrome-driven diagnosis of infectious diseases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34:561–70. 10.1007/s10096-014-2263-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubourg G, Lagier JC, Robert C, Armougom F, Hugon P, Metidji S, et al. Culturomics and pyrosequencing evidence of the reduction in gut microbiota diversity in patients with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;44:117–24. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfleiderer A, Lagier JC, Armougom F, Robert C, Vialettes B, Raoult D. Culturomics identified 11 new bacterial species from a single anorexia nervosa stool sample. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:1471–81. 10.1007/s10096-013-1900-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi-Tamisier M, Benamar S, Raoult D, Fournier P-E. Cautionary tale of using 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity values in identification of human-associated bacterial species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;65:1929–34. 10.1099/ijs.0.000161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ndongo S, Khelaifia S, Bittar F, Fournier P-E, Raoult D. “Actinomyces ihumii,” a new bacterial species isolated from the digestive microbiota of a HIV-infected patient. New Microbes New Infect. 2016;12:71–2. 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fonkou MDM, Bilen M, Cadoret F, Fournier PE, Dubourg G, Raoult D. ‘Enterococcus timonensis’ sp. nov., ‘Actinomyces marseillensis’ sp. nov., ‘Leptotrichia massiliensis’ sp. nov., ‘Actinomyces pacaensis’ sp. nov., ‘Actinomyces oralis’ sp. nov., ‘Actinomyces culturomici’ sp. nov. and ‘Gemella massiliensis’ sp. nov., new bacterial species isolated from the human respiratory microbiome. New Microbes New Infect. 2017;22:37–43. 10.1016/j.nmni.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagier JC, Bibi F, Ramasamy D, Azhar EI, Robert C, Yasir M, et al. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Clostridium jeddahense sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2014;9:1003–19. 10.4056/sigs.5571026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dione N, Sankar SA, Lagier JC, Khelaifia S, Michele C, Armstrong N, et al. Genome sequence and description of Anaerosalibacter massiliensis sp. nov. New Microbes New Infect. 2016;10:66–76. 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramasamy D, Lagier JC, Rossi-Tamisier M, Pfleiderer A, Michelle C, Couderc C, et al. Genome sequence and description of Bacteroides timonensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2014;9:1181–97. 10.4056/sigs.5389564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Togo AH, Diop A, Dubourg G, Nguyen TT, Andrieu C, Caputo A, et al. Butyricimonas phoceensis sp. nov., a new anaerobic species isolated from the human gut microbiota of a French morbidly obese patient. New Microbes New Infect. 2016;14:38–48. 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham TP, Cadoret F, Tidjani Alou M, Brah S, Ali Diallo B, Diallo A, et al. ‘Marasmitruncus massiliensis’ gen. nov., sp. nov., ‘Clostridium culturomicum’ sp. nov., ‘Blautia provencensis’ sp. nov., ‘Bacillus caccae’ sp. nov. and ‘Ornithinibacillus massiliensis’ sp. nov., isolated from stool samples of undernourished African children. New Microbes New Infect. 2017;19:38–42. 10.1016/j.nmni.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angelakis E, Bibi F, Ramasamy D, Azhar EI, Jiman-Fatani AA, Aboushoushah SM, et al. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Clostridium saudii sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2014;9:8. 10.1186/1944-3277-9-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Padmanabhan R, Dubourg G, Lagier JC, Couderc C, Michelle C, Raoult D, et al. Genome sequence and description of Corynebacterium ihumii sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2014;9:1128–43. 10.4056/sigs.5149006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cresci M, Ibrahima Lo C, Khelaifia S, Mouelhi D, Delerce J, Di Pinto F, et al. Corynebacterium phoceense sp. nov., strain MC1T a new bacterial species isolated from human urine. New Microbes New Infect. 2016;14:73–82. 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mourembou G, Rathored J, Ndjoyi-Mbiguino A, Lekana-Douki JB, Fenollar F, Robert C, et al. Noncontiguous finished genome sequence and description of Gabonia massiliensis gen. nov., sp. nov. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;9:35–44. 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishra AK, Edouard S, Dangui NP, Lagier JC, Caputo A, Blanc-Tailleur C, et al. Non-contiguous finished genome sequence and description of Nosocomiicoccus massiliensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2013;9:205–19. 10.4056/sigs.4378121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mishra AK, Hugon P, Robert C, Raoult D, Fournier PE. Non contiguous-finished genome sequence and description of Peptoniphilus grossensis sp. nov. Stand Genomic Sci. 2012;7:320–30. 10.4056/sigs.3056450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guilhot E, Lagier JC, Raoult D, Khelaifia S. ‘Prevotella ihumii’ sp. nov. and ‘Varibaculum timonense’ sp. nov., two new bacterial species isolated from a fresh human stool specimen. New Microbes New Infect. 2017;18:3–5. 10.1016/j.nmni.2017.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bardet L, Cimmino T, Buffet C, Michelle C, Rathored J, Tandina F, et al. Microbial culturomics application for global health: noncontiguous finished genome sequence and description of Pseudomonas massiliensis strain CB-1T sp. nov. in Brazil. OMICS. 2018;22:164–75. 10.1089/omi.2017.0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Dong D, Jiang C, Li Z, Wang X, Peng Y. Insight into alteration of gut microbiota in Clostridium difficile infection and asymptomatic C. difficile colonization. Anaerobe. 2015;34:1–7. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendy A, Vieira ER, Albatineh AN, Gasana J. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and long-term risk for death, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1966–9. 10.3201/eid2211.160220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewnard JA, Huppert A, Givon-Lavi N, Pettigrew MM, Regev-Yochay G, Dagan R, et al. Density, serotype diversity, and fitness of Streptococcus pneumoniae in upper respiratory tract cocolonization with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1411–20. 10.1093/infdis/jiw381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bilen M, Dufour JC, Lagier JC, Cadoret F, Daoud Z, Dubourg G, et al. The contribution of culturomics to the repertoire of isolated human bacterial and archaeal species. Microbiome. 2018;6:94. 10.1186/s40168-018-0485-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lagier JC, Dubourg G, Million M, Cadoret F, Bilen M, Fenollar F, et al. Culturing the human microbiota and culturomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:540–50. 10.1038/s41579-018-0041-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lagier JC, Dubourg G, Amrane S, Raoult D. Koch postulate: why should we grow bacteria? Arch Med Res. 2017;48:774–9. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2018.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]