Abstract

Human, dog, and cat fleas, as well as bedbugs, feed by biting their victims, causing acute prurigo, which is aggravated in sensitized victims (papular urticaria). The lesions appear in the classic "breakfast, lunch, and dinner" pattern. There are two main explanations: the parasites "map" the skin area in search of the best places to bite, and their removal when victim scratches, and then reattach to the skin. Treatments aim to control pruritus, as well as hypersensitivity reactions when necessary. Prevention is based on environmental control measures. The "breakfast, lunch, and dinner" sign is a definitive marker for diagnosis and the parasite´s identification and control.

Keywords: Bedbugs, Flea infestations, Parasites, Prurigo

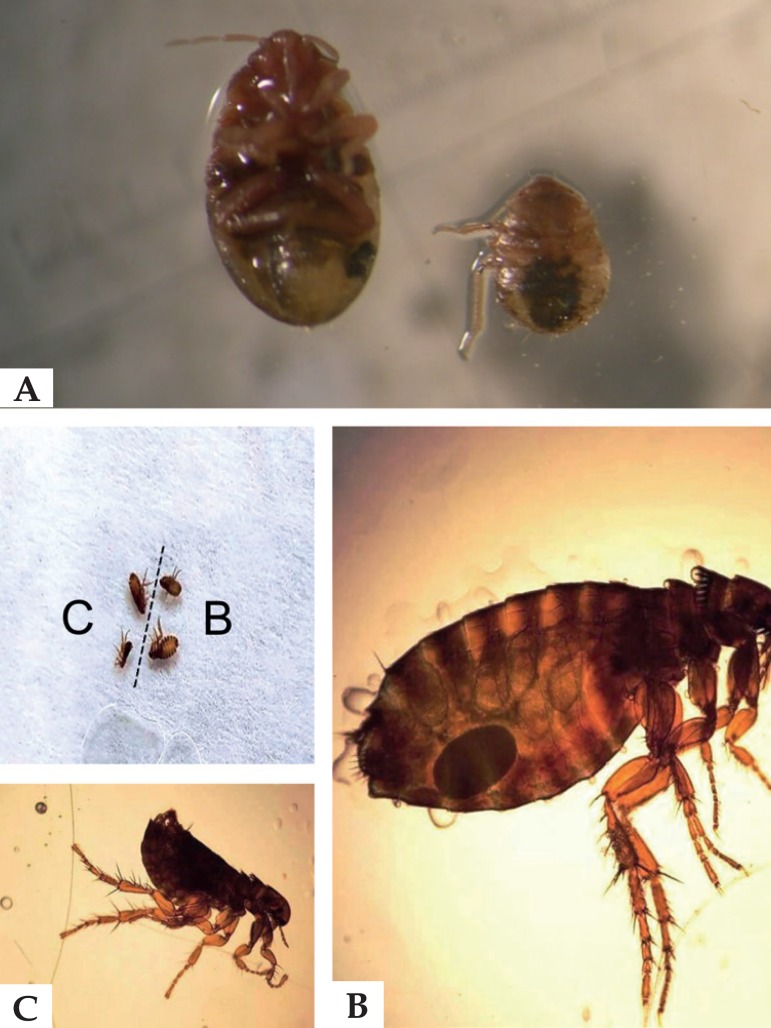

Skin lesions of varying severity can be caused by fleas of humans (Pulex irritans) and dogs and cats (Ctenocephalides canis and Ctenocephalides felis), as well as bedbugs (Cimex lectularius and Cimex hemipterus), which are bloodsucking arthropod parasites that commonly inhabit carpets, cracks in floor tiles, bedroom furniture, and cracks in walls (Figure 1).1-4 Bedbugs respond to aggregation pheromones, resulting in clustering behavior, although solitary bedbugs may be found.5 The capacity of bedbugs to act as disease vectors is debatable. However, pathogens have been detected in these insects, including the hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses, HIV, and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.6

Figure 1.

A - Bedbugs (Cimex lectula rius); B - cat flea (Ctenocephali des felis felis); C - dog flea (Ctenocephali des canis)

Images: Vidal Haddad Júnior and Gabriel Peres

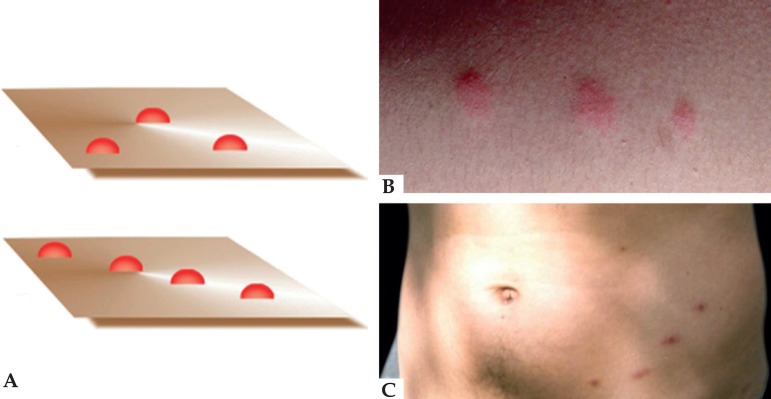

Bites by these arthropods are common and are usually associated with acute prurigo, and especially allergenic in atopic individuals, in whom they lead to papular urticaria. Contrary to bites by other bloodsucking arthropods, flea and bedbug bites frequently display a pattern that identifies the offending agent. Diagnosis is based on clinical observation, showing three or more bites (in most cases three) with pruritic, erythematous-edematous papules in a linear array (old citation in the literature) or triangular, a few centimeters apart. This pattern is known as the "breakfast, lunch, and dinner" sign (Figure 2).3-11 A bedbug bite usually appears as a small dot without an inflammatory reaction. Some patients may have only asymptomatic purpuric macules or papular urticaria with central purpura.6

Figure 2.

A - Scheme showing variations in the "breakfast, lunch, and dinner" pattern suggestive of infestation with fleas or be dbugs; B - papules caused by dog flea bites (Ctenocephalides canis); C - bedbug bites (Cimex lectularius)

Images: Gabriel Peres, Vidal Haddad Júnior, and João Luiz Costa Cardoso.

Bedbug bites usually occur on the face, neck, hands, and arms and can be noticed upon waking or one to several days later. The bite itself is painless. Bedbugs are rarely seen by the patient.7 There may be bacterial infection secondary to scratching. Most individuals that develop intense papular and pruritic reactions (papular urticaria) are atopic, and the lesions occur from hypersensitivity reactions, but anaphylaxis does not occur.3-11

The "breakfast, lunch, and dinner" pattern of urticariform papules is characteristic of infestation with human, canine, and feline fleas as well as bedbugs.3-11

There are two explanations (not mutually exclusive) for the lesions' pattern: prior mapping of the skin areas by the parasites and successive blood meals.11,12 Before feeding, the fleas and bedbugs mark the most favorable skin area using salivary apyrase, an anticoagulant enzyme. The enzyme's action itself can already induce local hypersensitivity.12 Once they have attached to the human´s skin, the arthropods begin their blood meal, which can be interrupted by the host´s sudden movement or clothes friction. When the meal is interrupted, the arthropods soon find another nearby site to feed, which can favor the mechanism of sequential bites.11,12

Symptomatic treatment includes antihistamines to control the itching and reduction of the allergic response and topic corticoids for regression of the lesions.3,4,11

Preventive measures consist of eliminating the parasites from the environment (indoors and yards) and from the preferentially infested domestic animals. Patients should be oriented not to scratch the lesions in order to avoid secondary bacterial infections caused by contamination of the injured skin with the animal's feces and bacteria. Patients should also avoid warm baths in order not to amplify the reactional process and aggravate the pruritis.3,4,11

We thus conclude that the "breakfast, lunch, and dinner" sign is extremely useful for identifying the agent in cases of acute pruritis and serves to optimize environmental measures for parasite control, which vary according to each species.

Footnotes

Work conducted at the Department of Dermatology and Radiotherapy, Faculdade de Medicina de Botucatu, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu (SP), Brazil.

Conflict of interest: None.

AUTHORS'CONTRIBUTIONS

Gabriel Peres

0000-0001-7923-443X

Preparation and writing of the manuscript, Collecting, analysis and interpretation of data, Critical review of the literature, Critical review of the manuscript

Lara Buonalumi Tacito Yugar

0000-0003-3485-9000

Preparation and writing of the manuscript, Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of studied cases, Critical review of the literature

Vidal Haddad Junior

0000-0001-7214-0422

Approval of the final version of the manuscript, Design and planning of the study, Preparation and writing of the manuscript, Collecting, analysis and interpretation of data, Effective participation in research orientation, Intellectual participation in propaedeutic and/or therapeutic conduct of studied cases, Critical review of the literature, Critical review of the manuscript

REFERENCES

- 1.Youssefi MR, Rahimi MT. Extreme human annoyance caused by Ctenocephalides felis felis (cat flea) Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014;4:334–336. doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corpus LD, Corpus KM. Mass flea outbreak at a child care facility: case report. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:497–498. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.4.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haddad Jr V, Cardoso JL, Lupi O, Tyring SK. Tropical dermatology: venomous arthropods and human skin: part I: Insecta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:331.e1–331.14. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haddad Jr V, Cardoso JL, Lupi O, Tyring SK. Tropical dermatology: venomous arthropods and human skin: part II: Diplopoda, Chilopoda and Arachnida. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:347.e1–347.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saenz VL, Santangelo RG, Vargo EL, Schal C. Group living accelerates bed bug (Hemiptera: Cimicidae) development. J Med Entomol. 2014;51:293–295. doi: 10.1603/me13080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358–1366. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elston DM, Stockwell S. What's eating you? Bedbugs. Cutis. 2000;65:262–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander JO. Arthropods and Human Skin. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1984. pp. 159–176. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goddard J. Physician's Guide to Arthropods of Medical Importance. 6th Edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juckett G. Arthropod bites. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddad Junior V, Amorim PC, Haddad Junior WT, Cardoso JL. Venomous and poisonous arthropods: identification, clinical manifestations of envenomation, and treatments used in human injuries. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:650–657. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0242-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheeseman MT. Characterization of apyrase activity from the salivary glands of the cat flea Ctenocephalides felis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;28:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(98)00093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]