Abstract

Objective:

To assess the performance of Texkat, the largest Hurricane Katrina Medicaid Emergency Waiver, in providing care to asthmatic children.

Methods:

Medicaid enrollment and encounter data for 2004 and 2006 from Louisiana and Texas were analyzed in a pre-post comparison. Changes in utilization by children in the waiver was compared to changes in utilization by children in Medicaid in three control groups: children in Louisiana counties that were designated a disaster assistance area but who were not displaced; children in Louisiana counties that were not designated as a disaster assistance area, and children in Texas. The analysis included prescriptions for controller and quick-relief medications as well as encounters in inpatient, emergency, outpatient, and office settings.

Results:

The sample proportion of TexKat enrollees who had a prescription filled for controller medications fell from 0.37 to 0.28 between 2004 and 2006. By contrast, the sample proportions for the three control groups were relatively unchanged or increased. The inferential analysis indicated that the 2004–2006 change in proportions for the TexKat group differed from the changes for each of the three control groups (p-value < .001). For office and emergency department visits, the 2004–2006 decreases in both the proportion of subjects with a visit and the average number of visits for the TexKat group were greater than the changes for the control groups (p-value < .001).

Conclusions:

While TexKat appears to have largely been successful in preventing extreme utilization disruptions, the analysis suggests that children in the program may have received inadequate care.

Keywords: Disaster, Children, Medicaid, Hurricane Katrina, Displacement

Introduction

Hurricane Katrina was the costliest hurricane in U.S. history and was directly responsible for 1200 deaths [1]. The August 2005 storm led to the displacement of 1.5 million people [2] and four months after Katrina struck, 85% of those under the age of 18 had not returned to their homes [3]. Those displaced were largely from vulnerable populations and 60% earned less than $20,000 per year prior to the hurricane [4].

A large proportion of children who were displaced suffered from lower respiratory issues before Katrina. A survey of children at healthcare facilities in New Orleans after Katrina found that before the storm 17.5% had asthma or lung disease [5], while a similar survey found that nearly 10% had experienced lower respiratory symptoms [6]. An analysis of 2003 data from the National Survey of Children’s Health estimated an asthma prevalence rate of 14% among children living in urban areas in Louisiana [3].

Unsurprisingly, the displacement led to significant disruptions in care. A survey of roughly 1000 displaced adults found that nearly 10% of adults with asthma experienced a treatment disruption [7]. However, an analysis of 182 children in affected areas found that the locations of asthma care were relatively similar after Katrina [8].

One of the primary tools used by policymakers to address the healthcare needs of vulnerable populations affected by Katrina were Section 1115 Medicaid Emergency Waivers. These federal waivers allowed states to expedite Medicaid coverage to displaced individuals by streamlining documentation and income requirements. Waivers were issued to 17 states with TexKat, the Texas waiver program, being the largest. [9] TexKat included a one-month, urgent medical care delivery phase and a health care coverage phase. The coverage phase was in operation through July 2006 and was capped at five months of coverage per enrollee. TexKat served nearly 60,000 enrollees, of which 97% came from Louisiana [10].

The goal of this study was to assess how well TexKat provided care to asthmatic children. While Medicaid Emergency Waivers are one of the most important mechanisms by which the federal government can provide medical care to low-income populations following a disaster, little is known regarding their performance [10,11,12]. The few studies that have analyzed these waivers have not specifically examined asthma, despite its relatively high prevalence among low-income children [13,14]. The findings in this study may help policymakers determine whether future waivers need to be restructured to ensure that vulnerable children with asthma receive appropriate care.

The analysis compared the rates of medication utilization and encounters before and after Katrina for children in TexKat to the rates of children in control groups. The individual-level claims data that were employed potentially provide a more complete perspective than data typically used in disaster studies. First, the administrative nature of the data avoided recall bias and other potential issues that can affect survey data that have been typically used to investigate Katrina. Second, the data were longitudinal and provided a relatively complete view of utilization both before and after the storm. Finally, the data allowed for comparisons to control groups that could serve as measures for potential changes in utilization that are not related to Katrina.

Methods

Study Sample

This study employed the Medicaid Analytic (MAX) enrollment and encounter claims data for Louisiana and Texas from 2004 to 2006. The data contained identifiers that allowed for tracking individuals both over time and across states, thus providing a relatively complete picture of their health care. The enrollment data included variables that identified TexKat enrollees and the length of their participation in the program.

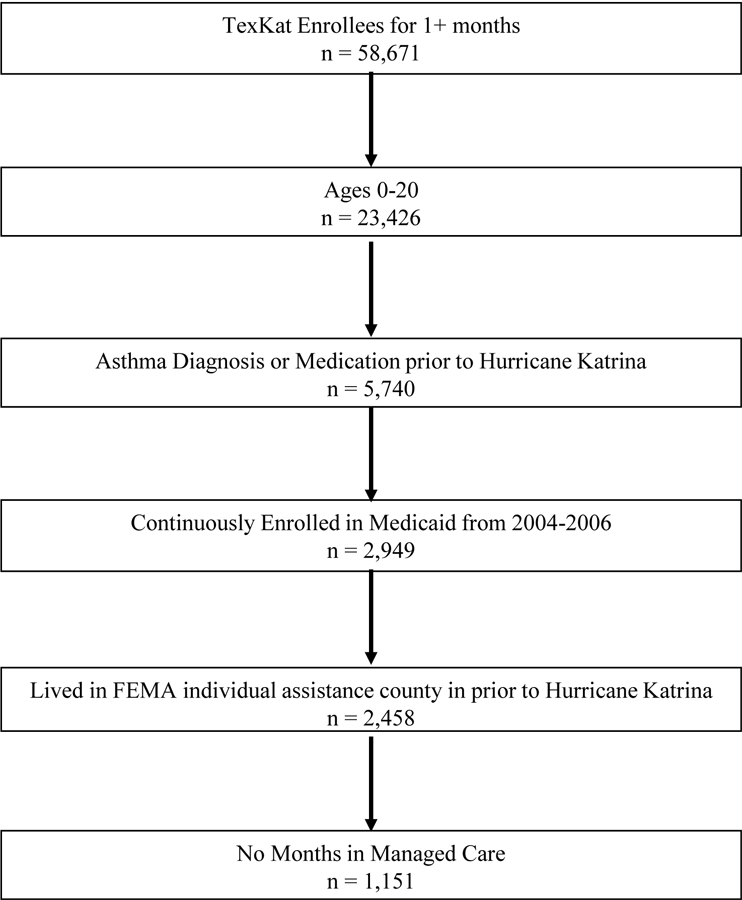

Figure 1 depicts the inclusion of TexKat enrollees in the study sample. The sample was first limited by TexKat participation and age. The sample was further limited to those who had an encounter involving an ICD-9-CM code of 493X or an asthma medication prescription [15] filled in the period from January 2004 to July 2005. To avoid under-reporting of utilization (encounters and medications) due to outside insurance coverage, the group was further limited to those who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid. Next, the group was limited to those whose pre-Katrina address was in a FEMA-designated disaster county [16]. Finally, because the MAX files generally do not contain claims for those enrolled in Medicaid managed care plans, the group was further limited to those who had no months of managed care enrollment.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of subject inclusion into treated group.

While changes in utilization by those in the TexKat group could suggest the effects of displacement following Katrina, they could also reflect other factors not related to the storm. For instance, a hypothetical decrease in utilization could at least be partially attributed to children who were diagnosed or received medications in the pre-Katrina period but whose asthma improved to where treatment was no longer necessary. To address this issue, control groups were identified whose utilization should have been either less or not affected by Katrina. The data for the three control groups were also obtained from the MAX files and share the TexKat criteria involving age, pre-Katrina asthma diagnosis or medication, continuous enrollment in Medicaid, and no months in managed care. The control group LA – Disaster consists of those who also lived in a disaster zip code prior to Katrina but did not relocate to Texas. This group provides a potential counter-factual for if the enrollees had not been displaced. LA – Nondisaster consists of all those who lived in a Louisiana zip code that was not declared a disaster area and were enrolled in Louisiana Medicaid for every month. Finally, TX contains subjects who were enrolled in Texas Medicaid for every month.

Table 1 contains demographic data for the TexKat and control groups, as well as enrollment data for the TexKat enrollees. The TexKat and control groups had similar gender distributions. The TexKat age distribution was marginally older than the control groups, most so relative to the TX group. However, the biggest difference across groups was by race/ethnicity. While the TexKat group was 93% black, the two LA groups were just over 50% and the TX group was less than 15%. To address this issue, the inferential analysis below is performed both for all subjects and for blacks only. The average length of participation in the TexKat program was 4.5 months, while two-thirds of participants were enrolled for the maximum coverage period of five months. Roughly two-thirds of the treated group first enrolled in 2005 and one-third of the total enrollment period took place in 2005.

Table 1.

Characteristics of TexKat and control group subjects.

| Variable | TexKat (N=1151) |

LA – Disaster (N=62,317) |

LA – Non- Disaster (N=45,982) |

TX (N=100,580) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 45.5 | 46.5 | 46.2 | 45.4 |

| Male | 54.5 | 53.5 | 53.8 | 54.6 |

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 9.0 +− 4.9 | 8.6 +− 4.7 | 8.7 +− 4.7 | 7.5 +− 4.6 |

| 0–4 years old | 22.7 | 24.7 | 24.0 | 34.9 |

| 5–9 years old | 34.2 | 34.9 | 35.0 | 32.9 |

| 10–14 years old | 26.5 | 26.0 | 26.3 | 22.0 |

| 15–20 years old | 16.6 | 14.4 | 14.6 | 10.2 |

| Race / ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 93.0 | 54.8 | 53.6 | 13.6 |

| White | 2.5 | 39.4 | 39.9 | 17.8 |

| Hispanic | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 66.1 |

| Asian | 2.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Other | 0.7 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 2.2 |

| Months enrolled in TexKat | 4.6 +− 1.0 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Outcomes

The two outcomes of interest were prescriptions for asthma medications and patient encounters involving an asthma diagnosis. The medication measure was the proportion of subjects who had at least one prescription in that year. The analysis was subset by whether the medication was a controller or quick-relief. A primary concern was whether the use of controller medications was reduced for those who were displaced, potentially leading to asthma attacks.

Encounters were classified by the service setting: physician office visits, hospital outpatient visits, emergency department visits, and inpatient stays. The encounters were measured in two ways: the proportion of subjects who had an encounter in that year and the average number of encounters per year per enrollee. Generally, physician office and hospital outpatient visits are associated with relatively controlled asthma, while emergency department visits and inpatient stays are indications of poorly controlled asthma. Given inpatient encounters were very infrequent, they were excluded in the inferential analysis of the average number of encounters.

Data before and after Katrina were utilized to allow for comparisons of differences over time, which partially controlled for inherent differences across groups that did not vary over time. Because of concerns regarding the reliability of data immediately following Katrina, 2005 data were excluded and the analysis was limited to calendar years 2004 and 2006.

Inference was performed by calculating t-tests that compare the 2004–2006 changes in the measure (proportion or average number of visits) for the TexKat group to each of the three control groups. A significance level of 0.05 was used in the discussion below.

Results

Medications

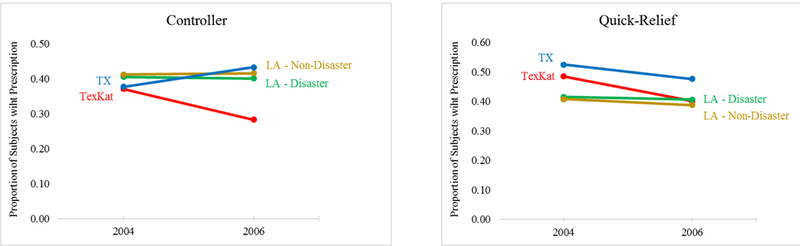

Figure 2 displays the sample proportions of subjects in the groups who had an asthma prescription filled in 2004 and 2006. The first panel shows the proportions for controller medications, while the second shows them for quick-relief medications. The proportion of subjects who had a filled prescription for a controller medication in 2004 ranged relatively little from roughly 37% for the TexKat group to just over 41% for the LA-Nondisaster group. However, especially noteworthy is the differences in changes from 2004 to 2006 across the four groups. Whereas the proportions for the control group were either virtually unchanged or even increased, the proportion for the TexKat group fell by almost 9%. Further, the 2006 sample proportions range from 40% to over 50% higher in the control groups.

Figure 2.

Proportion of subjects per year with a prescription by year, treatment/control group, and medication type, 2004 and 2006.

A slightly different picture emerges for quick-relief medications. The TexKat proportion was substantially greater than both of the LA proportions but somewhat less than the TX proportion. The proportions for all of the groups fell in 2006, but the drop was most pronounced for the TexKat group. Table 2 reports the results of inferential tests of the equivalence of the changes in proportions between 2004 and 2006. The first column of data contains the change for TexKat subjects, while the next three sets of columns correspond to the three control groups. The top section of the table contains data for all subjects, while the lower half is based on blacks only. Within each section, the changes for controller and quick-relief prescriptions are reported separately. For instance, the first cell in the table indicates that the proportion of subjects with a controller prescription in the TexKat group fell by 0.088 between 2004 and 2006 with a standard deviation of 0.018. The cell to the right shows that the proportion of LA-Nondisaster subjects who had a prescription increased by 0.003 from 2004 to 2006. The upper value in the next cell to the right reports the difference between the two changes. The lower number is the p-value for the test of the equivalence of the change in proportion for the TexKat group relative to that control group.

Table 2.

Change in proportion of subjects with a prescription, all subjects and blacks only, 2004–2006.

| TexKat |

LA - Nondisaster |

LA - Disaster |

TX |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population / Prescription Type |

Changea (SD) |

Changea (SD) |

Differenceb (p-value) |

Changea (SD) |

Differenceb (SD) |

Changea (Std Dev) |

Differenceb (SD) |

| All | |||||||

| Controller | −0.088 | 0.003 | −0.091 | −0.005 | −0.083 | 0.056 | −0.144 |

| (0.018) | (0.003) | (0.0000) | (0.003) | (0.0000) | (0.002) | (0.0000) | |

| Quick-Relief | −0.084 | −0.021 | −0.064 | −0.009 | −0.075 | −0.048 | −0.036 |

| (0.020) | (0.003) | (0.0005) | (0.003) | (0.0001) | (0.002) | (0.0652) | |

| N | 1,151 | 45,982 | 62,317 | 100,580 | |||

| Blacks only | |||||||

| Controller | −0.097 | −0.003 | −0.094 | −0.027 | −0.070 | 0.041 | −0.138 |

| (0.019) | (0.004) | (0.0000) | (0.003) | (0.0004) | (0.005) | (0.0000) | |

| Quick-Relief | −0.087 | −0.023 | −0.064 | −0.034 | −0.053 | −0.035 | −0.052 |

| (0.021) | (0.004) | (0.0009) | (0.003) | (0.0069) | (0.005) | (0.0109) | |

| N | 1,070 | 24,643 | 34,137 | 13,651 | |||

The top number in each cell is the change in sample proportion from 2004–2006 and the bottom is the standard deviation.

The top number in each cell is the difference between the TexKat change and the change for that control group, while the bottom number is the p-value from a t-test of the equivalence of the TexKat change and the change for that control group.

The estimates in Table 2 indicate that the 2004–2006 changes in the TexKat proportion were generally statistically significantly different than those of the control groups. For instance, the change for the TexKat controller proportion was 0.091 less than the LA-Nondisaster proportion (p-value 0.000). The estimates in the top row indicate that for controller medications for all subjects the p-values for each of the three tests were zero. The changes for quick-relief medications for all subjects were also statistically different for the two LA groups, but not for TX. To ensure that the estimates were not driven by racial differences between the TexKat and the control groups, the inferential analysis was also performed with the groups limited to black children. The results in the bottom section of Table 2 indicate that the findings for all subjects generally hold for black children.

Encounters

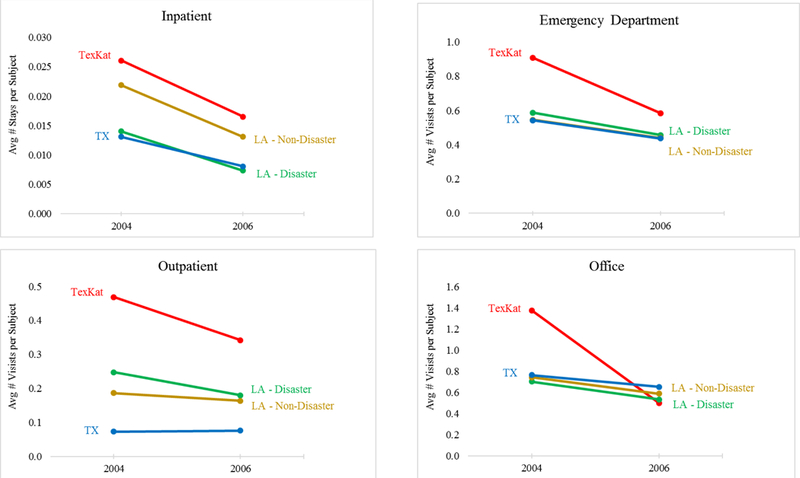

Figure 3 depicts the sample average number of encounters per enrollee per year for each of the four service settings: office, outpatient, emergency department, and inpatient. The sample averages dropped across nearly all settings and groups from 2004 to 2006. However, the starkest drop occurred in the office setting for the TexKat group, where the sample average fell by almost 0.9 visits from nearly 1.4 to just over 0.5. The next largest drop in the office setting was by less than 0.2 visits. However, the 2004 TexKat average was nearly twice as high as those of the comparison groups. Further, the 2006 average was roughly similar to that of the LA – Disaster group.

Figure 3.

Average number of encounters per subject by year, treatment/control group, and service setting, 2004 and 2006.

The outpatient and emergency department charts are somewhat similar to the office chart. All groups experienced a decrease in the sample average, with both the largest 2004 values and 2004–2006 drops occurring in the TexKat group. However, unlike in the office setting, the TexKat 2006 sample averages are greater than those of the control groups.

Table 3 contains the results of inferential tests as to whether the 2004–2006 changes in the average number of encounters differed statistically between the TexKat and control groups. The structure of the table is like that of Table 2, except the rows now refer to the various service settings. The estimates indicate that none of the changes in the average number of inpatient stays for the three control groups differed from the TexKat change. By contrast, the changes were different for all of the control groups for emergency and office visits and for both LA groups for outpatient visits (pvalues < .0002). The bottom half of Table 3 reports a similar pattern when the groups are limited to black children.

Table 3.

Change in proportion of subjects with an encounter, all subjects and blacks only, 2004–2006.

| TexKat |

LA - Nondisaster |

LA - Disaster |

TX |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population / Service Setting |

Changea (SD) |

Changea (SD) |

Differenceb (p-value) |

Changea (SD) |

Differenceb (SD) |

Changea (Std Dev) |

Differenceb (SD) |

| All | |||||||

| Inpatient | −0.007 | −0.007 | 0.000 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.006 | −0.001 |

| (0.172) | (0.158) | (0.9912) | (0.127) | (0.4837) | (0.131) | (0.7586) | |

| Emergency | −0.109 | −0.041 | −0.067 | −0.035 | −0.073 | −0.041 | −0.067 |

| (0.018) | (0.002) | (0.0000) | (0.002) | (0.0000) | (0.002) | (0.0000) | |

| Outpatient | −0.012 | −0.007 | −0.006 | −0.002 | −0.010 | −0.014 | 0.002 |

| (0.011) | (0.001) | (0.4881) | (0.001) | (0.1540) | (0.001) | (0.7934) | |

| Office | −0.091 | −0.043 | −0.048 | −0.037 | −0.055 | −0.035 | −0.056 |

| (0.017) | (0.002) | (0.0006) | (0.002) | (0.0002) | (0.002) | (0.0002) | |

| N | 1151 | 45,982 | 100,580 | 62,317 | |||

| Blacks only | |||||||

| Inpatient | −0.007 | −0.007 | 0.000 | −0.007 | 0.000 | −0.007 | 0.000 |

| (0.173) | (0.179) | (0.9465) | (0.156) | (0.9406) | (0.148) | (0.9735) | |

| Emergency | −0.117 | −0.041 | −0.076 | −0.040 | −0.077 | −0.065 | −0.052 |

| (0.019) | (0.003) | (0.0000) | (0.005) | (0.0000) | (0.003) | (0.0022) | |

| Outpatient | −0.017 | −0.006 | −0.010 | −0.006 | −0.011 | −0.020 | 0.004 |

| (0.012) | (0.002) | (0.2779) | (0.003) | (0.3309) | (0.002) | (0.7317) | |

| Office | −0.097 | −0.044 | −0.053 | −0.043 | −0.054 | −0.058 | −0.040 |

| (0.017) | (0.003) | (0.0005) | (0.004) | (0.0009) | (0.003) | (0.0133) | |

| N | 1070 | 24,643 | 13,651 | 34,137 | |||

The top number in each cell is the change in sample proportion from 2004–2006 and the bottom is the standard deviation.

The top number in each cell is the difference between the TexKat change and the change for that control group, while the bottom number is the p-value from a t-test of the equivalence of the TexKat change and the change for that control group.

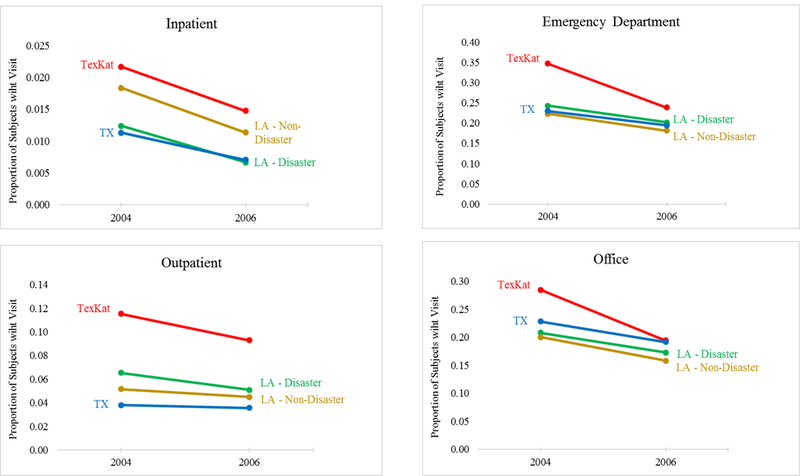

Rather than show the average number of encounters, Figure 4 details the proportion of subjects who had at least one encounter. The pattern is similar to Figure 3 in that the TexKat group experienced relatively large drops in the sample proportions for office and emergency department encounters. Table 4 shows that the changes in proportions were only significantly statistically different for the emergency and office settings (pvalues < .0007). Again, the results are relatively unaffected when the population is limited to blacks.

Figure 4.

Proportion of subjects per year with an encounter by year, treatment/control group, and service setting, 2004 and 2006.

Table 4.

Change in average number of encounters per subject, all and blacks only, 2004–2006.

| TexKat |

LA - Nondisaster |

LA - Disaster |

TX |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population / Service Setting |

Changea (SD) |

Changea (SD) |

Differenceb (p-value) |

Changea (SD) |

Differenceb (p-value) |

Changea (Std Dev) |

Differenceb (p-value) |

| All | |||||||

| Emergency | −0.325 | −0.105 | −0.220 | −0.106 | −0.219 | −0.135 | −0.190 |

| (0.061) | (0.008) | (0.0000) | (0.005) | (0.0000) | (0.007) | (0.0001) | |

| Outpatient | −0.115 | −0.023 | −0.091 | 0.003 | −0.117 | −0.068 | −0.047 |

| (0.055) | (0.006) | (0.0151) | (0.002) | (0.0000) | (0.006) | (0.2567) | |

| Office | −0.877 | −0.154 | −0.723 | −0.112 | −0.765 | −0.170 | −0.707 |

| (0.124) | (0.013) | (0.0000) | (0.009) | (0.0000) | (0.011) | (0.0000) | |

| N | 1,151 | 45,982 | 100,580 | 62,317 | |||

| Blacks only | |||||||

| Emergency | −0.349 | −0.088 | −0.261 | −0.128 | −0.221 | −0.193 | −0.155 |

| (0.064) | (0.011) | (0.0000) | (0.015) | (0.0000) | (0.010) | (0.0077) | |

| Outpatient | −0.129 | −0.024 | −0.105 | −0.011 | −0.118 | −0.093 | −0.036 |

| (0.059) | (0.009) | (0.0218) | (0.007) | (0.0002) | (0.009) | (0.4802) | |

| Office | −0.913 | −0.199 | −0.714 | −0.169 | −0.744 | −0.311 | −0.602 |

| (0.131) | (0.018) | (0.0000) | (0.021) | (0.0000) | (0.016) | (0.0000) | |

| N | 1,070 | 24,643 | 13,651 | 34,137 | |||

The top number in each cell is the change in the sample average number of encounters from 2004–2006 and the bottom is the standard deviation.

The top number in each cell is the difference between the TexKat change and the change for that control group, while the bottom number is the p-value from a t-test of the equivalence of the TexKat change and the change for that control group.

Discussion

The analysis revealed utilization differences between TexKat enrollees and the subjects in the control groups. In terms of controller medications, the TexKat group not only had the lowest sample proportion with a prescription in 2004, but was the only group that experienced a large drop in sample proportions between 2004 and 2006. The inferential analysis showed that the 2004–2006 decrease for the TexKat group was statistically different from the changes for the control groups. Further, the TexKat 2004–2006 decrease was statistically significantly greater than the change for the two LA control groups for quick-relief medications.

The TexKat group also experienced a statistically larger drop in the average number of emergency department and office visits, but the changes in other service settings were relatively in line with the control groups. Taken together, while the utilization of the TexKat group did not drop dramatically across all categories of medications and encounters, it appears that significant disruptions may have occurred.

The challenges faced by individuals and providers in the aftermath of Katrina were daunting. The heroic efforts put forth by families and professionals to maintain health care to those displaced by the storm clearly helped many. However, the findings in this paper suggest that the care to some asthmatic children was interrupted and may have led to complications. Perhaps policymakers can build on the strengths of Medicaid emergency waivers to prevent similar disruptions following future disasters.

While the data employed in this analysis provided unique insight, there were significant limitations to the findings. Utilization was observed only for those who were displaced to Texas and not to other states. While limiting the sample to those who were continuously enrolled and who were not in managed care provided greater confidence that the data reflected all of their utilization, it also reduced the sample sizes and may have created selection bias if these subjects were not representative of all Medicaid enrollees. Further, while data were not available for care received outside of Medicaid, this concern was mitigated by restricting the analysis to subjects who were continuously enrolled.

Conclusion

Hurricane Katrina was a devastating natural disaster and the TexKat program performed admirably given the scale of the challenges it faced. Nevertheless, the analysis suggested that the vulnerable population it served experienced care disruptions that may have led to health deterioration. The findings can potentially be used to investigate how to better serve those impacted by future disaster.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jill Herndon, Judy Wendt Hess, and Sean Gregory for their helpful comments. This study was Supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under award number R03HD079758. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Blake ES, Landsea CW, Gibney EJ, Asheville N. The deadliest, costliest, and most intense US tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2006 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts) NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6. http://www.srh.noaa.gov/www/images/tbw/1921/DeadliestHurricanes.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed October 27, 2012

- 2.Groen J, Polivka A. Hurricane Katrina evacuees: who they are, where they are, and how they are faring. Mon Labor Rev 2007;131(3):32–51. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abramson DM, Garfield RM. On the Edge: Children and Families Displaced by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita Face a Looming Medical and Mental Health Crisis 2006. Available at http://www.ncdp.mailman.columbia.edu/files/LCAFH.pdf. Accessed April 13, 2013.

- 4.Texas Health and Human Services Commission. Katrina evacuees in Texas. 2006 Available at: http://www.hhsc.state.tx.us/survey/KATRINA_0806_FinalReport.PDF.

- 5.Rath B, Donato J, Duggan A, et al. Adverse Health Outcomes after Hurricane Katrina among Children and Adolescents with Chronic Conditions. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 2007;18(2):405–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rath B, Young EA, Harris A, et al. Adverse respiratory symptoms and environmental exposures among children and adolescents following Hurricane Katrina. Public Health Reports 2011;853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kessler R Hurricane Katrina’s Impact on the Care of Survivors with Chronic Medical Conditions. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2007;22:1225–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chulada PC, Kennedy S, Mvula MM, et al. The Head-off Environmental Asthma in Louisiana (HEAL) Study—Methods and Study Population. Environmental Health Perspectives 2012;120(11):1592–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser Family Foundation. A Comparison of the Seventeen Approved Katrina Waivers 2006.

- 10.Texas Health and Human Services Commission. Final Report on the Katrina Medicaid Demonstration 2006.

- 11.Calicchia M, Greene R, Lee E, Warner M. Disaster Relief Medicaid Evaluation Project. Research Studies and Reports 2005. Available at http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/reports/6.

- 12.Haslanger K Radical Simplification: Disaster Relief Medicaid In New York City. Health Affairs 2003;22(1):252–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark NM, Lachance L, Benedict MB, et al. The extent and patterns of multiple chronic conditions in low-income children. Clinical Pediatrics 2015;54(4);353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malhotra K, Baltrus P, Zhang S, et al. Geographic and racial variation in asthma prevalence and emergency department use among Medicaid-enrolled children in 14 southern states. Journal of Asthma 2014;51(9);913–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS 2011 NDC lists: use of appropriate medications for people with asthma (ASM) Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2011. Available at: http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/1274/Default.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 16.Federal Emergency Management Administration. Designated Areas: Louisiana Hurricane Katrina. 2005 Available at: http://www.fema.gov/disaster/1603/designated-areas.