Abstract

DHEA and its sulfate derivative (DHEAS) decline with age. The decline in DHEAS levels has been associated with many physiological impairments in older persons including cognitive dysfunction. However, data regarding the possible relationship between DHEAS and cognition are scant. We investigated whether DHEAS levels are associated with presence and development of lower cognitive function measured by the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) in older men and women. One thousand and thirty-four residents aged ε65 yr of the InCHIANTI Study with data available on DHEAS and MMSE were randomly selected. MMSE was administered at baseline and 3 yr later. Among these, 841 completed a 3-yr follow-up. Parsimonious models obtained by backward selection from initial fully-adjusted models were used to identify independent factors associated with MMSE and DHEAS. The final analysis was performed in 755 participants (410 men and 345 women) with MMSE score ε21. A significant age-related decline of both DHEAS levels (p<0.001) and MMSE score (p<0.001) was found over the 3-yr follow-up. At enrolment, DHEAS was significantly and positively associated with MMSE score, independently of age and other potential confounders (®±SE 0.003±0.001, p<0.005). Low baseline DHEAS levels were predictive of larger decline of MMSE and this relationship was significant after adjusting for covariates (®±SE–0.004±0.002, p<0.03). Our data show a significant and positive association between DHEAS and cognitive function, assessed by MMSE test. Low DHEAS levels predict accelerated decline in MMSE score during the 3-yr follow-up period.

Keywords: Cognitive function, DHEAS, elderly

INTRODUCTION

DHEA and its sulfate derivative (DHEAS) are the major secretory products of the adrenocortical gland, and are produced in quantities larger than any other steroid hormone. The levels of DHEA and DHEAS decline with age in both sexes. This fall in circulating levels of DHEA/S occurs concurrently with the onset of many of the common physiological and functional impairments typically encountered in older persons (1–3).

Intervention studies in animals strongly support a putative role of DHEA/S descent in the pathogenesis of age related cognitive impairment. A number of studies have demonstrated that administration of these steroids enhances memory in several different models of young and aged animals and using various learning paradigms (4–7). In humans, several observational and intervention studies have been realized. In details, 2 large cross-sectional studies that examined the relationship between DHEAS and cognition have been recently published providing contrasting results. In the Massachusetts Male Aging Study, DHEAS level was not a significant independent correlate of cognition (8). In the Endogenous Androgen Levels in Women across the Adult Life Span Study,DHEAS levels were strong significant correlates of performance in certain cognitive measures (simple concentration and working memory) (9).

Baseline DHEAS levels were not predictors of differential cognition decline in 3 large prospective cohort studies involving males and females in the Rancho Bernardo Study (10), females in the Study of the Osteoporotic Fractures (11), and males in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (12). However, trends toward an inverse association between DHEAS and rate of cognitive decline were found in other 2 prospective cohort studies involving both men and women, namely a French community based cohort study (13) and a study performed in a small sample of healthy older subjects in the population-based Rotterdam study (14).

Five randomized controlled intervention trials have been carried out to evaluate the possible effect of DHEA treatment on cognitive performance (15–19). In these studies, the only significant improvement was on the attention performance following stress in one of the trials (17). In light of the conflicting results between animal and human studies, and because little of the human data come from a population-representative cohort including both men and women, we investigated whether DHEAS levels and cognitive function are related either cross-sectionally and/or longitudinally in the InCHIANTI Study. We addressed this question in these analytical steps: 1) to evaluate whether DHEAS levels are independently associated with cognitive function at baseline; 2) to evaluate whether lower baseline DHEAS levels are independently associated with greater decline in Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score over a 3-yr follow-up.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The study participants consisted of men and women, aged 65 yr and older, from 2 small towns in Tuscany, Italy, who participated in the InCHIANTI study (Aging in the Chianti Area). The study protocol was compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Italian National Institute of Research and Care on Aging Ethics Committee. The rationale, design, and data collection have been described in depth elsewhere (20, 21). Briefly, in August 1998, 1270 people aged 65 yr and older were randomly selected from the population registry of Greve in Chianti (population 11,709) and Bagno a Ripoli (population 4704). Of 1256 eligible subjects, 1155 (90.1%) agreed to participate. Of these 1155 participants, 1055 (91.3%) donated a baseline blood sample and underwent additional laboratory testing. The subjects who did not participate in the blood drawing were generally older and had greater co-morbidity than those who participated.

Participants were enrolled in the study after an extensive formal consenting process. Participants were re-evaluated at a 3-yr follow-up visit, conducted from 2001–2003, which included a phlebotomy and laboratory testing. Of the 1055 participants who donated a blood sample at baseline, 1034 (89.5%) participants had both baseline plasma DHEAS and MMSE score available for this analysis. Of these, 100 participants died between enrolment and the 3-yr follow-up. Of these 934 subjects, 841 also performed the 3-yr follow-up. After removing participants (no.=86) with low MMSE (score <21) at the enrolment measurement, we were left with data on 755 participants at 3 yr.

Measurements

Information collected at the initial clinic visit, using standardized methods included: age, education, anthropometrics [weight, height, body mass index (BMI)], physical activity assessment, physical functional performance, smoking, alcohol intake, health status, mood, blood pressure, lipid metabolism, cognitive function, and serum hormones concentrations [DHEAS, total testosterone (TTe), and estradiol (E2)].

Educational level was recorded as years of school. Weight was measured using a high-precision mechanical scale; standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm; BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Physical activity for the year before the interview was coded as: I) sedentary (completely inactive or light-intensity activity less than 1 h per week); II) light (light-intensity activity 2 to 4 h per week); or III) moderate to high (light activity at least 5 h per week or more, or moderate activity at least 1 to 2 h per week), using the modified standard version of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC Questionnaire) (21). Physical performance was evaluated using the Short Physical Performance Battery (22). Smoking history was determined by self-report and dichotomized in the analysis as current smoking vs not smoking (never smoked or smoked in the past). Usual alcohol intake was expressed in grams per day. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (23), with depression defined as a score of ≥16. Blood pressure was measured according to the standard pre-established criteria used in the Women’s Health and Aging Study (24). Total cholesterol serum concentration was assessed by commercial enzymatic test (Roche Diagnostic, GmbH. Mannheim, Germany) and a Roche-Hitachi 917 Auto-analyzer, with a minimum detectable concentration (MDC; analytical sensitivity) of 3.0 mg/dl and the intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV) 0.8% and 3.3%, respectively.

Cognitive function was evaluated using the MMSE test (25). The MMSE was administered by a trained examiner during the initial visit and again 3 yr later. MMSE is a brief cognitive battery (score <24 indicating poor performance) which evaluates orientation, concentration, language, praxis, and immediate and delayed memory. This screening test was originally created for a clinical setting and is extensively used in epidemiological studies (26). According to other studies, cognitive impairment was defined as MMSE score below 21 (27). In all of our analytic analyses, MMSE scores were corrected for age and education level using standard criteria (25).

Blood samples for the determination of hormones concentrations were collected in the morning after a 12-h fast. Aliquots of serum were immediately obtained and stored at–80 C. DHEAS, TTe, and E2 were assayed using commercial radioimmunological kits (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, Texas). For DHEAS, the MDC was 1.7 μg/dl; the intra-assay and inter-assay CV for 3 different hormone concentrations were 9.4% and 9.6% (at a concentration of 20.3 and 20.6 μg/dl), 7.8% and 10.0% (187.0 and 173.4 μg/dl), 6.3% and 9.94.6% (593.3 and 560.9 μg/dl), respectively. For TTe MDC was 0.08 ng/ml; the intra-assay and inter-assay CV for 3 different hormone concentrations were 9.6% and 8.6% (at a concentration of 0.94 and 0.70 ng/ml), 8.1%, and 9.1% (7.01 and 5.95 ng/ml), 7.8%, and 8.4% (19.71 and 16.06 ng/ml), respectively. For E2, MDC was 2.2 pg/ml and intra-assay and inter-assay CV for 4 different concentrations were8.9% and 7.5% (at a concentration of 5.3 and 5.3 pg/ml), 6.5% and 9.7% (24.9 and 28.0 pg/ml), 7.6% and 8.0% (40.4 and 42.3 pg/ml), and 6.9% and 12.2% (92.6 and 108.7 pg/ml), respectively.

Statistical analysis

Variables are reported as means (±SD) for normally distributed parameters or as percentages. Median and IQ (Q1-Q3) is reported for skewed variables.

Factors statistically correlated with MMSE were identified using age-adjusted partial correlation coefficients and Spearman partial rank-order correlation coefficients, as appropriate. Parsimonious models obtained by backward selection from initial fully adjusted models were used to identify independent factors associated with MMSE score [DHEAS, age, gender, BMI, physical activity, Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score, smoking status, alcohol intake, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), hypertension, total cholesterol, TTe, E2]. After exclusion of participants with low cognitive performance (MMSE score <21) at baseline, we tested the relationship between DHEAS values quartiles and change in MMSE score over the 3-yr follow-up, adjusting for all variables that were associated with DHEAS at enrolment and baseline MMSE score.

We also evaluated whether participants in the lowest DHEAS quartile at baseline were more likely associated to experience a reduction of ≥1 point on MMSE score at the 3-yr follow-up, compared to those in the higher quartiles after adjusting for confounders.

All analyses were performed using SAS (v. 8.2, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) with a statistical significance level set at p≤0.05.

RESULTS

The characteristics of the study population at enrolment and the subset of participants who were re-evaluated after three years are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 -.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| At baseline (no.=1043) | |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 75.5±7.1 |

| Female (no., %) | 453 (43.8) |

| Education (yr) | 5 [3–6] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4±4.1 |

| MMSE score | 24.3±5.0 |

| CES-D score | 11 [6–18] |

| Physical activity (no., %) | |

| Sedentary | 234 (22.6) |

| Light/moderate | 747 (72.3) |

| High | 53 (5.1) |

| Smoking current | 144 (13.9) |

| Alcohol Intake (current) | 10 [5.7–20] |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 217.1±40.0 |

| Hyperension (no., %) | 494 (47.7) |

| SPPB score | 11 [9–12] |

| DHEAS (μg/dl) | 65.0 [36.9–110.0] |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 8.1 [4.9–12.8] |

| Total testosterone (ng/ml) | 1.0 [0.6–4.0] |

BMI: body mass index; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SPPB: Short Physical Performance Battery.

Table 2 -.

Characteristics of the study population at the 3-yr of follow-up.

| At the 3-yr follow-up (no.=755) | |

|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 73.7.0±6.2 |

| Female (no., %) | 410 (54.3) |

| Education (yr) | 5 [4–6] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5±4.0 |

| MMSE score | 25.5±3.9 |

| CES-D score | 10 [6–17] |

| Physical activity (no., %) | |

| Sedentary | 122 (16.1) |

| Light/moderate | 591 (78.3) |

| High | 42 (5.6) |

| Smoking current (no., %) | 118 (16.0%) |

| Alcohol intake (current) (gr/day) | 10 [5.7–20] |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 220.0±37.9 |

| Hyperension (no., %) | 380 (46.7) |

| SPPB score | 11 [10–12] |

| DHEAS (μg/dl) | 69.3 [40.1–114.3] |

| Estradiol (pg/ml) | 8.1 [4.9–13.0] |

| Total testosterone (ng/ml) | 1.1 [0.6–4.21] |

BMI: body mass index; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SPPB: Short Physical Performance Battery.

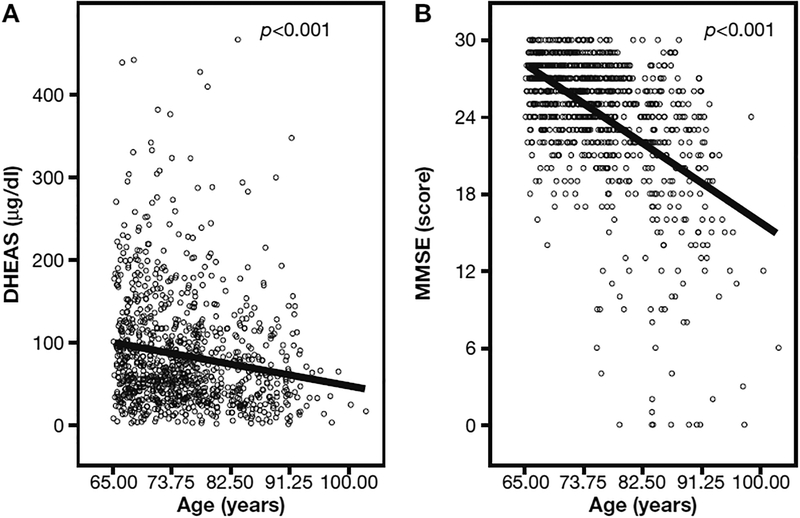

A significant age-related decline of both DHEAS serum concentration (p<0.001) and of MMSE score (p<0.001), were observed in our population (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 -.

Scatterplot and locally weighted least square regression line describing the relationship of age with DHEAS (left) and Mini Mental Scale Examination (MMSE) score (right) in the InCHIANTI study population at baseline.

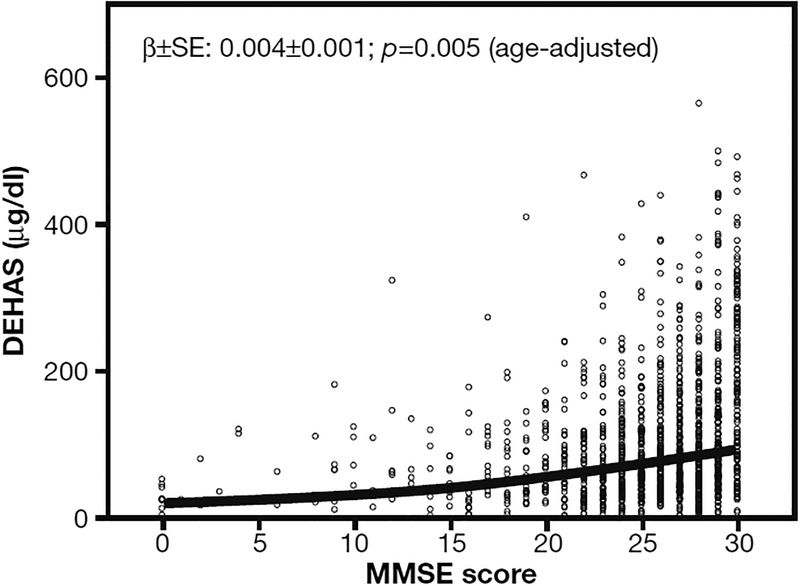

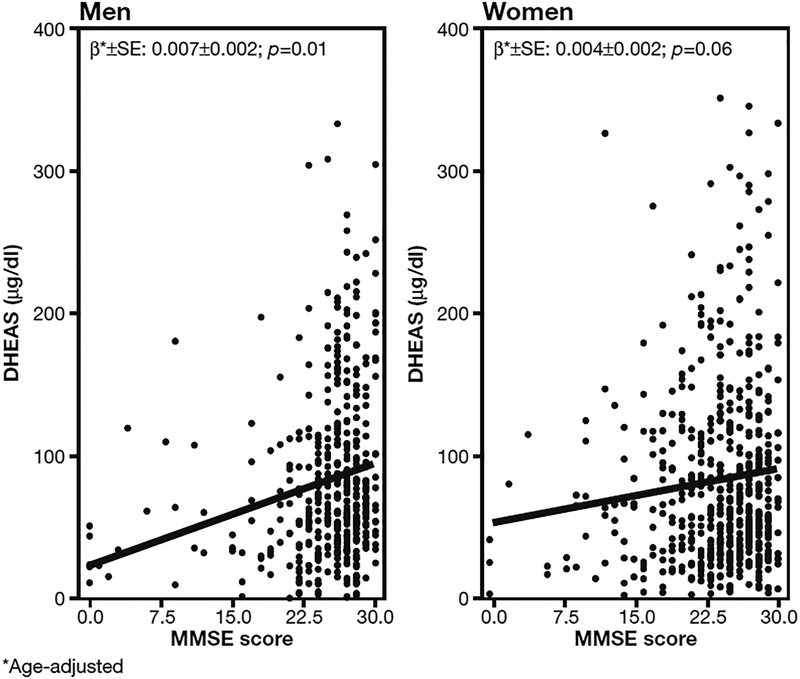

DHEAS concentration and MMSE score at baseline were correlated both in the general study population (Fig. 2; β coefficient 0.004±0.001 SD with p=0.005) and separately in men and women although in women was only borderline significant (Fig. 3; β coefficient 0.007±0.002 SD with p=0.01 in men and 0.004±0.002 SD with p=0.06 in women).

Fig. 2 -.

Scatterplot and locally weighted least square regression line describing the relationship of Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score with DHEAS serum levels. Note that MMSE score values are age adjusted at baseline in all the subjects age ≥65 in the InCHIANTI study.

Fig. 3 -.

Scatterplot and locally weighted least square regression line describing the relationship of Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score with DHEAS serum levels. Note that MMSE score values are age adjusted at baseline in all the subjects age ≥65 in the InCHIANTI study. The relationship is shown separately by gender.

The relationship between DHEAS and MMSE score at enrolment was examined using multivariate linear regression models (Table 3) in a crude analysis (model 1) and after adjusting for all appropriate covariates (model 2; β coefficient 0.003±0.001 SE with p<0.05). The analysis was performed in the global population and then stratified by gender. In men, DHEAS level was significantly and independently correlated with the MMSE score (fully adjusted model, β coefficient 0.005±0.002 SE with p=0.01), while in women we found only a borderline trend (β coefficient 0.004±0.002 with p=0.06). However, there was no significant “Gender*DHEAS” interaction in the regression model predicting MMSE score. Therefore subsequent analyses were performed jointly in men and women.

Table 3 -.

Regression models relating Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and DHEAS levels at baseline in crude, and fullyadjusted analyses in the whole study population. Model 2 shows the parsimonious model obtained by removing variables not significantly associated with the outcome by backward selection.

| Model 1* MMSE corrected at baseline | Model 2# MMSE corrected at baseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β±SE | p | β±SE | p | |

| DHEAS | 0.008±0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.003±0.001 | 0.01 |

Crude analysis.

Also adjusted for gender, body mass index, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol intake, estradiol, total testosterone, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), total cholesterol, hypertension, Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) score. Covariates were selected using a Pearson correlation coefficient <0.10.

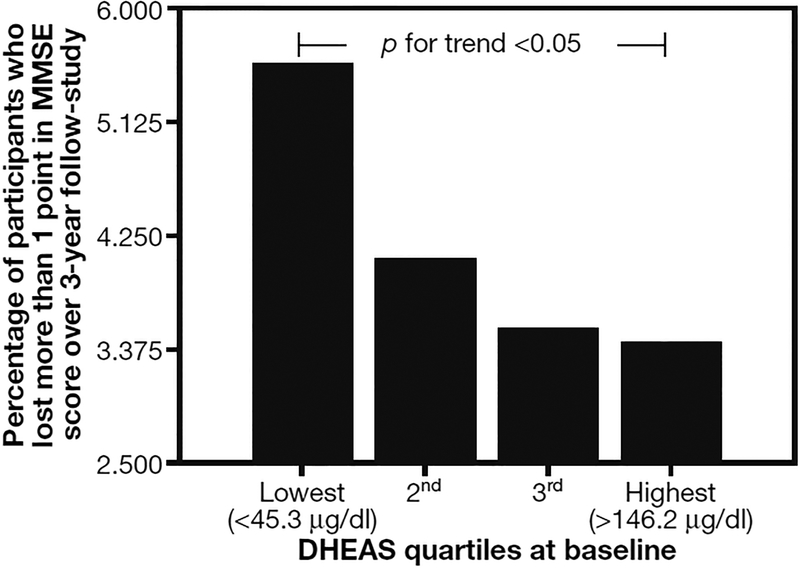

The relationship between DHEAS quartiles at enrolment and the percentage of participants who lost more than 1 point in MMSE during the 3-yr follow-up was higher in the lowest DHEAS quartiles (Fig. 4) (test for trend p<0.05). The quartile values of DHEAS were defined as follows: lowest quartile <45.3 μg/dl; 2nd quartile 45.3–77.8 μg/dl; 3rd quartile 77.8–146.2 μg/dl; highest quartile >46.2 μg/dl. As noted above, participants with MMSE scores <21 at baseline were excluded from the analysis. Low baseline DHEAS levels were predictive of larger decline and this relationship was significant after adjusting for covariates (Table 4) (β coefficient–0.004±0.002 SE with p<0.03). Note that only covariates significantly associated with changes in MMSE score (age, SPPB score, physical activity) are reported in this Table.

Fig. 4 -.

Percentage of participants who lost >1 point in Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score over the 3-yr follow-up period by DHEAS quartiles at baseline in the whole study population.

Table 4 -.

Regression models relating changes in Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) over 3-yr follow-up and DHEAS at baseline in fully adjusted analysis of the entire study population.

| Dep. change in MMSE score | ||

|---|---|---|

| β±SE | p | |

| DHEAS | –0.004±0.002 | 0.03 |

| Age | –0.067±0.03 | 0.002 |

| SPPB Score | 0.25±0.06 | <0.0001 |

| Physical activity (3 levels) | 0.68±0.29 | 0.02 |

Also adjusted for gender, smoking status, body mass index, alcohol in take, estradiol, total testosterone,Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), total cholesterol, hypertension. SPPB: Short Physical Performance Battery.

DISCUSSION

Our cross-sectional analysis of data from older participants in the population-based InCHIANTI study supports the hypothesis that low DHEAS may be associated with poorer cognitive status, as assessed by MMSE. In addition low DHEAS levels were independent predictors of accelerated decline in MMSE score over a 3-yr follow-up, suggesting that DHEAS may be directly involved in the modulation of cognitive performance.

The relationship between DHEAS and cognitive function remained significant even in a fully adjusted model, corrected for multiple potential confounders. Specifically, the interrelationship between DHEAS levels and MMSE scores was independent of both TTe and E2 concentrations, supporting the hypothesis that any putative biological effect as a neuro-steroid is directly related to DHEA/S itself, rather than through peripheral bioconversion to another androgenic or estrogenic steroid.

Our data are consistent with other cross-sectional studies available in literature. Davis et al. in a community-based cross-sectional study of highly educated 295 women showed a significant and independent association between serum DHEAS levels and domains of cognitive function including executive function, concentration, and working memory. However, that study was performed only in women with wider age-range (21–77 yr) and the cognitive tests were not simultaneously executed with hormonal measurements (9). By contrast Fonda et al. using data from men of the Massachussets Male Aging Study aged between 48 and 80 yr failed to find a significant association between DHEAS and cognitive function (8).

Our perspective data are at least partially consistent with those of Kalmijn et al. in the Rotterdam study showing an inverse and almost significant association between serum DHEAS levels and cognitive decline. However, in comparison with our study, the follow-up period was shorter (1.9 yr) with smaller number (no.=189) of participants (14). The same trend of association between DHEAS and MMSE was found by Berr et al. in a community-based study performed in subjects of both sexes similar for age range and follow-up period (13).

Moreover, our study is scarcely comparable with 3 other perspective studies showing different results (10–12). In fact Yaffe et al. analysing a smaller number of female subjects of similar age-range used osteoporotic fractures as primary outcome (11). In their study, Moffat et al. investigated the relationship between DHEAS and cognitive function in relatively high-functioning and well-educated men of Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging of wider age range [22–91] (12). Barrett-Connor et al., using data of 270 men and 167 women of Rancho Bernardo Study over 16–18-yr of follow-up, showed a significant relationship between DHEAS and cognitive function limited to Buschke selective reminding test and only in women (10). Despite the conflicting results of the literature, the strong and independent relationship between DHEAS and cognitive function assessed by MMSE observed in our study is not surprising. Pre-clinical studies suggest that there are several potential mechanisms by which DHEA/S affect brain trophism and neurotransmission. DHEA may play the role of a neuro-steroid through both genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. The first possibility is suggested by the in vitro findings that DHEA is capable of:a) reducing neuronal death and enhancing astrocitic differentiation (28) by activating cortico-thalamic projection growth in murine embryo (29); and b) facilitating in mice, the transcription of immediate-early genes that eventually lead to the synthesis of enzymes and/or structural proteins (30–33). The memory-enhancing effect of DHEA could also be achieved through non-genomic modulation of neurotransmission mechanisms: a) allosteric antagonism of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors (34,35); b) activation of N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (36); c) modulation of σ receptors (37); d) interference with muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (38); and e) dopamine and/or serotonine agonistic effects (39). Finally DHEA neuroprotection might occur through the attenuation of: a) the neurotoxic effects of certain aminoacids (40); b) oxidative stress (41); or c) glucocorticoid exposure (42).

An important possible mechanism explaining a DHEA/S effect on cognition, could occur through its direct or indirect effects (mostly inhibitory) on cortisol levels, metabolism, and action. An age-related overactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-cortisol axis has been well described in humans (43). This has been hypothesized to be a consequence of a progressive reduction in the usual hippocampal inhibitory control of the hypothalamus, as a result of morphological and biochemical changes caused by repeated stresses over the life span (44, 45). Elevated cortisol levels have been demonstrated to negatively impact cognitive status over time in several longitudinal, observational studies (14, 46–48). The possible mechanisms for the negative effect of glucocorticoids on cognition include disruption of synaptic plasticity and atrophy of dendritic processes, with impairment of the ability to withstand coincident insults (42). An age-related decline in DHEA/S could be one cause of a loss of hippocampal inhibition to the glucocorticoid system (49). In addition, DHEA/S may alter glucocorticoid activity by modulating cortisol metabolism (50). In this way, lower DHEA/S tone with aging might increase overall effective glucocorticoid activity at any given plasma cortisol concentration.

While our findings suggest that low initial DHEAS levels might represent a significant risk factor predisposing to age-related cognitive decline, in the face of mostly negative clinical trials in man, our study does not provide sufficient support for utilizing DHEA/S as a therapeutic tool to mitigate cognitive disorders at the present time. However, it is worthwhile considering that DHEA has been found to attenuate experimentally-induced amnesia in mice (51), while in humans, DHEA treatment was shown to promote a significant, albeit transient, effect on cognitive performance in patients with well-defined Alzheimer’s disease (52).

The major strengths of our study include: a) the population-based cohort with high (>90%) participation rates;b) the large number of older subjects evaluated; c) inclusion of both genders; d) the 3-yr longitudinal assessment of effect; and e) adjustment for several important potential confounders that could affect the relationship between DHEAS and cognition, including other sex steroids. Our study also has several important limitations. While DHEAS has a longer half-life than DHEA, and thus provides a more integrative measure, the use of a single measurement may not be as precise as an average of several separate determinations. Furthermore, by using an integrative measure, we lose the ability to assess any importance of the age-related flattening of diurnal variation of DHEA on other systems such as cortisol. The assessment of cognitive function in this study is limited to the global MMSE score, thus, we are unable to effectively evaluate potential effects on specific dimensions of cognitive performance.

We are aware that the ratio of DHEAS/cortisol might be a better marker for adrenocortical exposure than evaluating DHEAS alone. As discussed above, high cortisol levels have frequently been found to be associated with a decline in memory performance and therefore DHEAS levels should be considered in the context of the glucocorticoid activity. However, in this study we had only a single fasting morning cortisol available and inclusion of this variable as a covariate or as a ratio did not alter our results. Obviously, this leaves open the possible importance of cortisol activity measured in a more integrated manner (24-h urinary cortisol), as an explanation for our findings.

In conclusion, our data from the observational cross-sectional analysis of the InCHIANTI population-based study demonstrate a significant association between DHEAS serum levels and cognitive function, as determined by the MMSE test. While stronger in males, this finding is supported in both genders. A subsequent prospective evaluation of the cohort study after a 3-yr follow-up, suggests the possibility that low DHEAS levels might predict greater decline in MMSE score.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial disclosure

The InCHIANTI Study was supported as a “targeted project” (ICS 110.1/RS97.71) by the Italian Ministry of Health and in part by the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contracts N01-AG-916413 and N01-AG-821336) and by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institute on Aging (Contracts 263 MD 9164 13 and 263 MD 821336).

Sponsor’s role

The funding institutes had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, and preparation of manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose concerning this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Labrie F, Bélanger A, Cusan L, Gomez JL, Candas B. G. Marked decline in serum concentration of adrenal C 19 sex steroid precursor and conjugated androgen metabolites during aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82: 2396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjørnerem A, Straume B, Midtby M, et al. Endogenous sex hormones in relation to age, sex, lifestyle factors, and chronic disease in a general population: the Tromsø Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004, 89: 6039–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valenti G, Denti L, Saccò M, et al. ; GISEG (Italian Study Group on Geriatric Endocrinology). Consensus document substitution therapy with DHEA in the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res 2006, 18: 277–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markowski M, Ungeheuer M, Bitran D, Locurto C. Memory-enhancing effects of DHEAS in aged mice on a win-shift water escape task. Physiol Behav 2001, 72: 521–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fedotova J, Sapronov N. Behavioral effects of dehydroepiandrosterone in adult male rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2004, 28: 1023–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farr SA, Banks WA, Uezu K, Gaskin FS, Morley JE. DHEAS improves learning and memory in aged SAMP8 mice but not in diabetic mice. Life Sci 2004, 75: 2775–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sujkovic E, Mileusnic R, Fry JP, Rose SP. Temporal effects of dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate on memory formation in day-old chicks. Neuroscience 2007, 148: 375–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonda SJ, Bertrand R, O’Donnell A, Longcope C, McKinlay JB. Age, hormones, and cognitive functioning among middle-aged and elderly men: cross-sectional evidence from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005, 60: 385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis SR, Shah SM, McKenzie DP, Kulkarni J, Davison SL, Bell RJ. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate levels are associated with more favorable cognitive function in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008, 93: 801–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett-Connor E, Edelstein SL. A prospective study of dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, and cognitive function in an older population: the Rancho Bernardo Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994, 42: 420–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaffe K, Ettinger B, Pressman A, et al. Neuropsychiatric and dehydropeiandrosterone sulphate in elderly women: a prospective study. Biol Psychiatry 1998, 43: 694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Harman SM, et al. The relationship between longitudinal declines in dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate concentrations and cognitive performance in older men. Arch Inter Med 2000, 160: 2193–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berr C, Lafont S, Debuire B, Dartigues JF, Baulieu EE. Relationship of dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate in the elderly with functional, physiological and mental status, and short-term mortality: a French community-based study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93: 13410–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalmijn S, Launer LJ, Stolk RP, et al. A prospective study on cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate, and cognitive function in the elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998, 83: 3487–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf OT, Neumann O, Hellhammer DH, et al. Effects of a two-week physiological dehydroepiandrosterone substitution on cognitive performance and well-being in healthy elderly women and men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82: 2363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf OT, Naumann E, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone replacement in elderly men on event-related potentials, memory and well-being. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1998, 53: M385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolf OT, Kudielka BM, Hellhammer DH, Hellhammer J, Kirschbaum C. Opposing effects of DHEA replacement in elderly subjects on declarative memory and attention after exposure to a laboratory stressor. Psychoneuro endocrinology 1998, 23: 617–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnhart KT, Freeman E, Grisso JA, Rader DJ, Sammel M, Kapoor S, Nestler JE. The effect of dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation to symptomatic perimenopausal women on serum endocrine profiles, lipid parameters, and health-related quality of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999, 84: 3896–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Niekerk JK, Huppert FA, Herbert J. Salivary cortisol and DHEA: association with measures of cognition and well-being in normal older men, and effect of three months of DHEA supplementation. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2001, 26: 591–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrucci L, Bandinelli S, Benvenuti E, et al. Subsystems contributing to the decline in ability to walk: bridging the gap between epidemiology and geriatric practice in the InCHIANTI study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000, 48: 1618–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, et al. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy cost of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993, 25: 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, et al. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med 1995, 332: 556–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1977, 1: 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guralnik JM, Fried LP, Simonsick EM, Kasper D, Lafferty ME. The women’s health and aging study: health and social characteristics of older women with disability. Bethesda, MD, National Institute on Aging. NIH Publication; 1995, 95: 4009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975, 12: 189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Launer LJ. Overview of incidence studies of dementia conducted in Europe. Neuroepidemiology 1992, 11 (Suppl 1): 2–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination:a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992, 40: 922–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laurine E, Lafitte D, Grégoire C, et al. Specific binding of dehydroepiandrosterone to the N terminus of the microtubule-associated protein MAP2. J Biol Chem 2003, 278: 29979–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bologa L, Sharma J, Roberts E. Dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfated derivative reduce neuronal death and enhance astrocytic differentiation in brain cell cultures. J Neurosci Res 1987, 17: 225–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Compagnone NA, Mellon SH. Dehydroepiandrosterone: a potential signalling molecule for neocortical organization during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95: 4678–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts E, Bologa L, Flood JF, Smith GE. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone and its sulfate on brain tissue in culture and on memory in mice. Brain Res 1987, 406: 357–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flood JF, Roberts E. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate improves memory in aging mice. Brain Res 1988, 448: 178–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flood JF, Morley JE, Roberts E. Memory-enhancing effects in male mice of pregnenolone and steroids metabolically derived from it. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89: 1567–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majewska MD, Demirgoren S, Spivak CE, London ED. The neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate is an allosteric antagonist of the GABAA receptor. Brain Res 1990, 526: 143–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demirgören S, Majewska MD, Spivak CE, London ED. Receptor binding and electrophysiological effects of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, an antagonist of the GABAA receptor. Neuroscience 1991, 45: 127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monnet FP, Mahé V, Robel P, Baulieu EE. Neurosteroids, via sigma receptors, modulate the [3H]norepinephrine release evoked by Nmethyl-D-aspartate in the rat hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92: 3774–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong LY, Cheng ZX, Fu YM, et al. Neurosteroid dehydroepian-drosterone sulphate enhance a spontaneous glutamate release in rat prelimbic cortex through activation of dopamine D1 and sigma-1 receptors. Neuropharmacology 2007, 52: 966–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steffensen SC, Jones MD, Hales K, Allison DW. Dehydro epi andros-terone sulfate and estrone sulfate reduce GABA-recurrent inhibition in the hippocampus via muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Hippocampus 2006, 16: 1080–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abadie JM, Porter JR, Wright BE, Browne ES, Svec F. The effect of discontinuing dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation on Zucker rat food intake and hypothalamic neurotransmitters. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1995, 19: 480–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimonides VG, Khatibi NH, Svendsen CN, Sofroniew MV, Herbert J. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulfate (DHEAS) protect hippocampal neurons against excitatory amino acid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95: 1852–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bastianetto S, Ramassamy C, Poirier J, Quirion R. Dehydroepiandros-terone (DHEA) protects hippocampal cells from oxidative stress-induced damage. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1999, 66: 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimonides VG, Spillantini MG, Sofroniew MV, Fawcett JW, Herbert J. Dehydroepiandrosterone antagonizes the neurotoxic effects of corticosterone and translocation of stress-activated protein kinase 3 in hippocampal primary cultures. Neuroscience 1999, 89: 429–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O’Brien JT, Schweitzer I, Ames D, Tuckwell V, Mastwyk M. Cortisol suppression by dexamethasone in the healthy elderly: effects of age, dexamethasone levels, and cognitive function. Biol Psychiatry 1994, 36: 389–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sapolsky RM, Uno H, Rebert CS, Finch CE. Hippocampal damage associated with prolonged glucocorticoid exposure in primates. J Neurosci 1990, 10: 2897–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sapolsky RM. Glucocorticoids, stress, and their adverse neurological effects: relevance to aging. Exp Gerontol 1999, 34: 721–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lupien SJ, Gaudreau S, Tchiteya BM, et al. Stress-induced declarative memory impairment in healthy elderly subjects: relationship to cortisol reactivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82: 2070–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Singer BH, et al. Increase in urinary cortisol excretion and memory declines: MacArthur studies on successful aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82: 2458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carlson LE, Sherwin BB. Relationships among cortisol (CRT), dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEAS), and memory in a longitudinal study of healthy elderly men and women. Neurobiol Aging 1999, 20: 315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ceresini G, Morganti S, Rebechi I, et al. Evaluation on the circadian profiles of serum dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), cortisol, and cortisol/DHEA molar ratio after a single oral administration of DHEA in elderly subjects. Metabolism 2000, 49: 548–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Apostolova G, Schweizer RA, Balazs Z, Kostadinova RM, Odermatt A. Dehydroepiandrosterone inhibits the amplification of glucocorticoid action in adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005, 288: E957–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maurice T, Su TP, Privat A. Sigma1 (sigma 1) receptor agonist and neurosteroids attenuate B25–35-amyloid peptide-induced amnesia in mice through a common mechanism. Neuroscience 1998, 83: 413–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolkowitz OM, Kramer JH, Reus VI, et al. ; DHEA-Alzheimer’s Disease Collaborative Research. DHEA treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurology 2003, 60: 1071–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]