Abstract

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported infection. It can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility. Rates of gonorrhea decreased after the National Gonorrhea Control Program began in 1972, but stabilized in the mid 1990’s. The emergence of antimicrobial resistant strains increases the urgency for enhanced gonorrhea control efforts. In order to identify possible approaches for improving gonorrhea control, we reviewed historic protocols, reports, and other documents related to the activities of the National Gonorrhea Control Program using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention records and the published literature. The Program was a massive effort that annually tested up to 9.3 million women, and treated up to 85,000 infected partners and 100,000 additional exposed partners. Reported gonorrhea rates fell by 74% between 1976 and 1996, then stabilized. Testing positivity was 1.6–4.2% in different settings in 1976. In 1999–2008, the test positivity of a random sample of 14–25 year-olds was 0.4%. Gonorrhea testing rates remain high, however, partner notification efforts decreased in the 1990’s as attention shifted to HIV and other STDs. The decrease and subsequent stabilization of gonorrhea rates was likely also influenced by changes in behavior, such as increases in condom use in response to AIDS. Renewed emphasis on partner treatment might lead to further decreases in rates of gonorrhea.

Keywords: gonorrhea, control, screening, partner notification, history, surveillance

Brief summary:

The National Gonorrhea Control Program was a massive effort. Gonorrhea prevalence decreased due to screening, partner notification, and HIV-related changes in behavior. Emphasizing partner treatment might reduce rates further.

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported infection in the United States, with over 350,000 cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2014.1 Although infection is often asymptomatic,2 it is an important cause of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and infertility.3 Increasing rates of reported gonorrhea and new testing technology led to the establishment of The National Gonorrhea Control Program in 1972.4 Over the ensuing twenty years, reported rates fell by 74% from their peak level before stabilizing in the mid 1990’s. 1 The Gonorrhea Control Program never officially ended, but since the late 1980’s efforts of STD control programs gradually shifted to other priorities. Between 1994 and 2014 reported rates of gonorrhea have decreased by less than 10%.1

The persistently high rates of infection seen in the United States are troublesome beyond their implications for PID and infertility. The gonococcus has developed resistance to multiple antibiotics leaving cephalosporins as the last class of drugs with reliable ability to cure infection.5 Detecting and controlling the emergence of resistant strains would be easier if the rates of gonorrhea were lower. Furthermore, rates of gonorrhea are ten times higher in blacks than in whites,1 so reducing this longstanding disparity would help improve health equity.

Here, we review the activities of the National Gonorrhea Control Program and explore what might explain the dramatic decrease in rates, why rates subsequently stabilized, and what could be done to decrease rates even further. Better understanding the interventions, scale, and successes of the National Gonorrhea Control Program might inform efforts to control the current epidemic.

We explored the historic context of the National Gonorrhea Control Program by evaluating a range of primary and secondary literature. We reviewed gonorrhea surveillance data reported to CDC from 1963 to 2014 (originally called the VD Statistical Letter, most recently called Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance). We also reviewed the published literature to characterize the effort involved in the gonorrhea control program. During our review, we were most interested in the strategies, the magnitude of the effort, and the evidence of impact.

Control Program Implementation

Accurately diagnosing gonorrhea was often difficult until 1964 when Thayer and Martin developed a selective culture medium that made widespread testing for gonorrhea possible.6 At that time, gonorrhea was thought to be mostly asymptomatic in women and nearly always sufficiently noticeable and painful in men to motivate them to seek medical attention.7, 8 Therefore, when demonstration projects used this new test in several cities starting in 1968, they focused on finding and treating asymptomatic women.7–10 That effort expanded to become the National Gonorrhea Control Program in 1972, with an annual budget of $16 M (equivalent to $86 M in 2015) which was considerably more than the $6.3 M then appropriated for control of syphilis.4, 8, 11 Through the National Gonorrhea Control Program, CDC funded states which distributed culture plates to health care providers, to encourage screening of reproductive-age women when they had a pelvic exam. Additional efforts focused on finding and treating the female partners of infected men, education, and expanding the availability of screening and treatment.4, 8

Screening

In the beginning, the results of testing done by the National Gonorrhea Control Program were reported in the Statistical Letter. In 1973, there were 7,062,133 women tested and 322,746 (4.6%) tested positive. (Table 1) Testing in the program peaked in 1975 when over 9.3 million women were tested and 400,851 (4.3%) tested positive. Testing venues included many types of clinics in the public and private sector. (Table 2) Some of the “screening” tests were probably “diagnostic” tests performed because women were identified as exposed sex partners, or had symptoms or histories that suggested infection. For example, in fiscal year 1976, women tested in the STD clinic were more likely to test positive (19.0%) than women tested elsewhere (2.7%). Reported numbers of women tested with federally-funded tests remained high through at least 1985 when 7,481,500 were tested and 4.1% tested positive. After 1985 programs were no longer required to report on the number of tests performed. The amount of testing done outside of the federal program is not known, though it likely increased over time. For example, among all female gonorrhea cases reported to CDC, the percent of cases that were identified by the federal testing program dropped from 96.9% in 1976 to 78.8% in 1985 suggesting an increasing proportion of cases identified outside of the program. Because case reporting by private physicians was only about 11% during this time period,4, 12 this is likely an understatement of the amount of testing outside of the program. In 1993, additional funding was provided through the Infertility Prevention Project (IPP) to increase chlamydia and gonorrhea screening of sexually-active, low income women attending family planning, STD, and other women’s healthcare clinics.13 The numbers of tests funded through this project were not systematically collected.

Table 1.

Women tested for gonorrhea, and all cases of gonorrhea reported, 1973–1985.

| Women tested | Cases reported | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Tested | Positive | % | Women | Men | Total |

| 1973 | 7,062,133 | 322,746 | 4.6 | 332,800 | 509,821 | 842,621 |

| 1974 | 8,308,301 | 350,149 | 4.2 | 367,011 | 539,110 | 906,121 |

| 1975 | 9,310,618 | 400,851 | 4.3 | 406,183 | 593,754 | 999,937 |

| 1976 | 8,953,358 | 391,809 | 4.4 | 405,381 | 596,613 | 1,001,994 |

| 1977 | 8,456,410 | 393,305 | 4.7 | 404,193 | 598,026 | 1,002,219 |

| 1978 | 8,641,188 | 403,098 | 4.7 | 415,797 | 597,639 | 1,013,436 |

| 1979 | 8,778,406 | 392,283 | 4.5 | 413,295 | 590,763 | 1,004,058 |

| 1980 | 9,106,583 | 398,651 | 4.4 | 411,220 | 592,809 | 1,004,029 |

| 1981 | 8,904,745 | 385,057 | 4.3 | 402,616 | 588,248 | 990,864 |

| 1982 | 8,052,584 | 343,291 | 4.3 | 385,481 | 575,152 | 960,633 |

| 1983 | 7,720,860 | 319,102 | 4.1 | 374,064 | 526,371 | 900,435 |

| 1983 | 7,337,192 | 300,761 | 4.1 | 369,831 | 508,725 | 878,556 |

| 1985 | 7,481,500 | 305,667 | 4.1 | 386,856 | 524,563 | 911,419 |

Table 2.

Number of gonorrhea cultures and results, for women, by clinic type, U.S. July 1975–June 1976. Source ref 52

| Tests | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reporting Source | Number | Positive (%) |

| Venereal Disease Clinics | 885,709 | 19.0 |

| Other Health Department Clinics | 1,842,571 | 3.1 |

| Hospital outpatient | 1,530,372 | 4.2 |

| Hospital inpatient | 67,288 | 2.8 |

| Community Health Center | 779,798 | 3.0 |

| Private Physicians | 2,377,977 | 2.0 |

| Private Family Planning Groups | 959,206 | 1.6 |

| Group Health Clinics | 137,181 | 2.1 |

| Student Health Centers | 228,454 | 1.7 |

| Others, or not specified | 300,708 | 3.2 |

| Total | 9,109,264 | 4.3 |

Partner Notification

Another critical component of the National Gonorrhea Control Program was partner notification, which was emphasized to find additional persons with asymptomatic gonorrhea. Health department staff focused on finding female partners of symptomatic men because infected men were thought to almost always seek care,7, 8 and male partners of female patients had often already been treated.14 In 1973, the federal partner notification program interviewed 183,610 patients, which led to examination of 134,890 partners of whom 52,703 (39.1%) were brought to treatment for an infection, and a similar number of partners were treated for possible incubating infection. (Table 3) The partner notification program peaked in 1980 when 390,334 patients were interviewed (38.9% of the 1,004,029 total reported cases), 230,059 partners were examined and 85,338 (37.1%) infected partners were brought to treatment. These infected partners represented 8.5% of all cases diagnosed and reported to CDC that year. The partner notification numbers were quite different for males and females, partly due to who was pursued in investigations. For example, at the Denver STD clinic, 19.4% of all infections were derived from contact investigations, 5.7% of male cases, and 47.1% of female cases.15

Table 3:

Partner treatment for gonorrhea, 1973–1985

| Index cases | Partners | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected and brought to treatment,* |

Treated based on exposure** |

Total treated | |||||

| Year | Number | Interviewed | Named | Number | per index case | Number | per index case |

| 1973† | 813,750 | 183,610 | 186,073 | 52,703 | 0.065 | 61,846 | 0.14 |

| 1974† | 878,576 | 305,279 | 301,942 | 79,972 | 0.091 | 92,501 | 0.20 |

| 1975 | 999,937 | 309,360 | 315,805 | 84,019 | 0.084 | 94,661 | 0.18 |

| 1976 | 1,001,994 | 325,457 | 321,356 | 84,782 | 0.085 | 101,829 | 0.19 |

| 1977 | 1,002,219 | 326,319 | 303,826 | 76,156 | 0.076 | 88,729 | 0.16 |

| 1978 | 1,013,436 | 357,916 | 330,921 | 81,101 | 0.080 | 89,606 | 0.17 |

| 1979 | 1,004,058 | 367,703 | 351,169 | 79,901 | 0.080 | 95,146 | 0.17 |

| 1980 | 1,004,029 | 390,334 | 380,169 | 85,338 | 0.085 | 100,648 | 0.19 |

| 1981 | 990,864 | 360,272 | 335,345 | 79,392 | 0.080 | 92,272 | 0.17 |

| 1982 | 960,633 | 356,549 | 321,013 | 73,825 | 0.077 | 84,550 | 0.16 |

| 1983 | 900,435 | 342,220 | 302,190 | 69,680 | 0.077 | 82,688 | 0.17 |

| 1984 | 878,556 | 362,031 | 301,687 | 70,085 | 0.080 | 78,469 | 0.17 |

| 1985 | 911,419 | 362,578 | 290,581 | 68,680 | 0.075 | 75,775 | 0.16 |

Had a positive test, and was treated.

Did not have a positive test; was treated because history suggested high likelihood of incubating infection.

Fiscal year.

Partner notification efforts changed over time, largely as a result of increased understanding of the asymptomatic nature of gonorrhea. In 1974, Handsfield reported that previous estimates of the proportion of men with gonorrhea who were symptomatic were biased because the studies were based on men attending STD clinics whereas screening in other settings identified many infected men who were (and remained) asymptomatic.16 Similarly, partner notification studies based in STD clinics were biased because the studies enrolled symptomatic men whereas women who were enrolled had originally been brought to the clinic because of their partners. Success in finding infected partners was not so much related to gender as it was to whether the interviewed patient was discovered as a result of screening (partners often remain infected) or as a result of partner notification (partners already treated).16 Consistent with those findings, in 1976, a study of 100 women with gonococcal PID found 63 (39%) of 161 male partners had untreated gonorrhea, of whom 14 (22%) were asymptomatic.17 These data led to a revised recommendation that included partner notification for male partners of women with PID.17 A later study compared partner investigations beginning with women with PID to investigations beginning with women who had positive screening tests and found no major differences in the number of male contacts infected (22.9% vs 25.4%) or infected partners who were asymptomatic (59% vs 49%).18 The high yield of asymptomatic male partners suggested that partner notification efforts should include partners of women with PID or positive screening tests for gonorrhea.19

It is difficult to tell how many patients might have notified their own partners without the federally funded program, and what the net impact of partner notification was. Two studies showed that giving patients a card to give to their partners worked just as well as sending out a disease investigator,15, 20 at a tiny fraction of the cost ($0.65 vs $42 per infection found).15 However most studies have found that more partners were notified when public health workers took responsibility for notifying partners.21 For example, one study found partners were more likely to be brought in for testing if health department personnel went out looking for them (80/221, 36%) than if patients were counselled on how to bring their partners in (57/457, 12%).22 Between 1975 and 2004, gonorrhea partner notification efforts reported in the literature were bringing 1 infected partner in for treatment for every 4 patients interviewed.21 By 1999, the emergence or recognition of other sexually transmitted infections, including HIV and chlamydia, made systematically offering health department based partner services beyond the reach of most large programs, and health departments were only involved with partner notification for about 17% of gonorrhea cases.23

Control Program Impact

Reported cases

The impact of the National Gonorrhea Control Program on disease incidence is difficult to discern from changes in reported cases. Although reported cases reflect trends in gonorrhea incidence, that reflection is distorted by changes in testing, reporting, and test technology that are incompletely documented or understood. Infections are usually asymptomatic, especially among women, so detection often depends on screening.2 In 2008, estimates of the incidence of gonorrhea suggested that only about 40% of infections were detected and reported.24 At the beginning of the control program (1972–1975), increased screening of women led to increases in the number of reported cases among women. Three other changes were noted during this period: (1) improved diagnostics for men meant fewer cases of non-gonococcal urethritis would be reported as gonorrhea; (2) the case definition was changed to stop including persons whose only evidence of infection was that they were treated because their partners had gonorrhea; and (3) reporting by private physicians increased (it was estimated to be only 11% in 1968).12 A study in 1974 used 3 methods to estimate that reporting by private physicians was 2.7% –24% complete.25 Later studies have documented the incompleteness of gonorrhea reporting.26 One study in 2001 found electronic lab reporting was much more complete (95%) than traditional reporting (57%),27 suggesting that reporting is likely to be better now than in the past. Gonorrhea culture has largely been replaced by nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) which are almost as specific (99.8% in one report)28 and more sensitive (which allows testing of urine from men or self-collected vaginal swabs).29 Further, gonorrhea and chlamydia NAATs are often combined on the same test strip and run on the same specimen so the number of women tested for gonorrhea has likely increased as testing for chlamydia increased. The number of chlamydia tests done every year is not known, however, according to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measure, testing of sexually active 21–24 year old women attending commercial HMOs testing increased from 16.0% in 1999 to 51.6% in 2014.30 Other groups monitored by the National Committee for Quality Assurance had similar increases in chlamydia (and presumably gonorrhea) testing.30

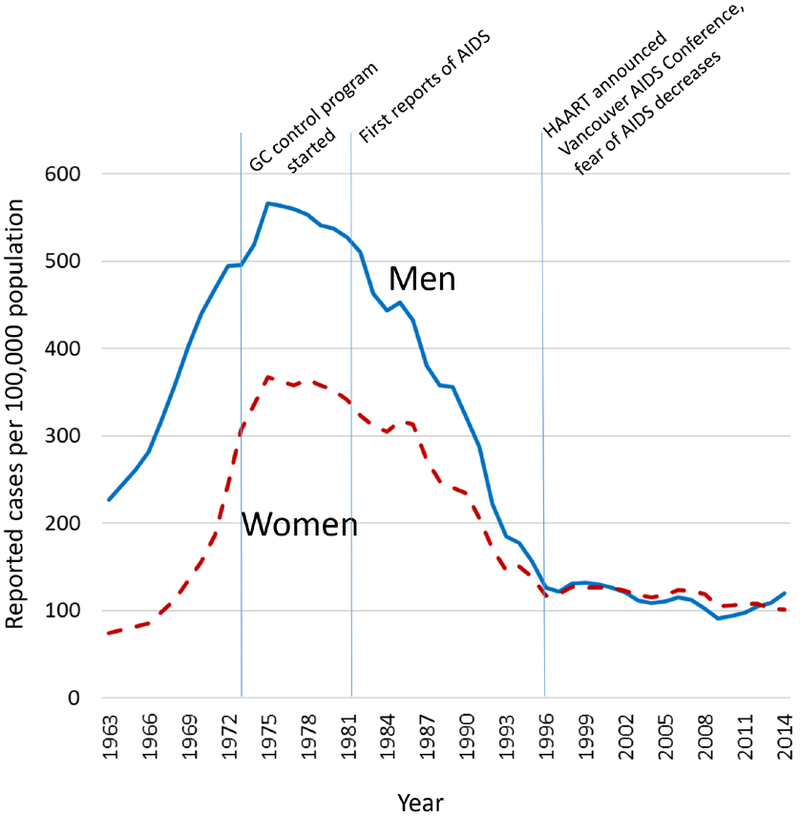

Gonorrhea reports have been collected at CDC since 1941. The variables collected and formatting have changed over time, however, anatomic site of infection and sex-of-sex-partner have not been routinely collected. Reported cases of gonorrhea began increasing in about 1963 when there were 278,289. (Figure) In 1963, most cases were symptomatic men diagnosed by clinical exam or gram stain; the male:female rate ratio was 3.1. The male:female rate ratio decreased as women were screened in the screening program, it stabilized at about 1.6 between 1973 and 1982, then decreased gradually to 1.0 in 1997. Since the program began, 15–24-year-olds have accounted for 66%–76% of cases among women and 45%–61% of cases among men. Gonorrhea has also consistently been more commonly reported among black persons compared to white persons. Although race is missing from many cases reported to CDC, the black:white rate ratio nationally was 10.3 in 1981, increased to 40.2 in 1993 (associated with an increase in use of crack cocaine),31 and then decreased to 10.3 in 2014. In 1975 the rates of reported gonorrhea for 20–24-year-olds were: for males, 14.0% among nonwhites and 1.1% among whites; and for females, 6.6% among nonwhites and 0.8% among whites.32 By 2014 the over-all reported rate of gonorrhea in the U.S. had fallen to 0.11%, 0.24 times what it had been in 1975. Annual rates among 20–24 year olds in 2014 were: for males, 1.7% among blacks and 0.16% among whites; and for females 1.8% among blacks and 0.19% among whites (race was missing for 18.6%).1

Figure.

Rates of reported cases of gonorrhea, by sex, United States, 1963–2014

Population based surveys and sentinel surveillance

In 2001–2002 the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health found the prevalence of gonorrhea among 18–26 year olds was 0.43% (95% CI, 0.29%−0.63%). It was higher in black males (2.4%) than white males (0.07%), and higher in black females (1.9%) than white females (0.13%).33 In a nationally representative sample of 14–25-year-olds in the United States (NHANES), the prevalence of gonorrhea was 0.40% (95% CI, 0.20%−0.72%) in 1999–2008.34 Subsequently, the gonorrhea prevalence was too low to permit precise tracking of changes over time in NHANES. 34 Sentinel surveillance can provide an alternative to case reports for monitoring changes in the prevalence of gonorrhea. Sentinel surveillance often has the advantage of providing information about the number of persons tested, which allows the calculation of positivity or prevalence among those tested. A study of the prevalence among 16–24 year old men and women entering the National Job Training Program found a 40–50% decrease in prevalence between 2004 and 2009, while rates of reported gonorrhea in the United States decreased by only 12.7%35 during that period, suggesting that trends in reported infections might be partially due to increases in testing.

Sequelae

Among women with untreated gonococcal cervicitis, 10–40% will develop symptomatic PID.36 These are rough estimates because there is no ethical way to observe a group of women with untreated infections to determine the incidence of PID among women with gonorrhea. Among women with PID, sequelae include involuntary infertility in 16–18%, ectopic pregnancy in 0.6–9%, and chronic pelvic pain in 18–29%.3 PID is difficult to measure precisely because it is usually a clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, asymptomatic PID can damage the tubes of women who never knew they had an infection. Despite the measurement issues, it is clear that there have been very large decreases in symptomatic PID.3 Estimated visits to physicians for PID decreased from 407,000 in 1993 to 88,000 in 2013.1 Hospitalizations for PID decreased by 68%, between 1985 and 2001, which may be partially explained by a shift toward outpatient treatment, however, there was also a (harder to quantify) decrease in PID diagnosed in ambulatory settings.37 Other studies found PID was decreasing at rates of 3.4 to 6.5% per year between 1996 and 2007 using a variety of methods.38–41

Contextual factors that may have influenced gonorrhea trends

Trends in demographics and sexual behavior have likely influenced trends in gonorrhea. The sexual revolution of the 1960’s–1970’s (the pill, increased numbers of sexual partners) likely played a role in the increase in gonorrhea.42 The baby boom changed the structure of the US population;32 15–24 year olds (the group with highest rates of gonorrhea) were 6.8% of the population in 1960 and 9.5% in 1975.43 The AIDS epidemic (identified in 1981) likely contributed to decreases in gonorrhea, by increasing condom use, decreasing sexual behavior that would lead to exposure to gonorrhea, and reducing the pool of highly sexually active gay men, because many became ill or died from AIDS. Condom use increased among heterosexuals between 1982 and 1995, especially among young blacks who were at highest risk for gonorrhea (from 6% to 33% among 20–24 year-olds),44 only to stabilize or decrease since 199645 when the effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was announced in Vancouver and concern about acquiring HIV decreased.46 These trends in condom use since 1982 mirror trends in gonorrhea (figure). Decreases in gonorrhea among men who have sex with men47 undoubtedly contributed to the decreases in gonorrhea among men in the 1980’s, though the exact amount is difficult to estimate because sex-of-sex-partner information is not available for reported cases, and many other factors influenced changes in the male:female rate ratio.

Discussion

The prevalence of gonorrhea clearly declined between the 1970’s when 1.6–4.2% of women had positive screening tests in various settings, (Table 2) and the early 2000’s when 0.43% of a representative sample of all 18–26 year olds were infected.33 However, the populations tested in these time periods were different, so the exact amount of the decrease remains uncertain. As with many other public health campaigns, there were no randomized controlled trials that tested the effects of the different components of the control program. The major factors contributing to the success appear to be the large size of the effort (equal to $86 million in 2015 dollars per year), extensive screening, and widespread partner notification. Society-level trends also had an impact on infection rates. Increases in gonorrhea were likely fueled by increases in sexual activity and mixing during the sexual revolution of the 1960’s and decreases were partly caused by changes in response to the AIDS epidemic in 1982–1997.31 The gonorrhea control program began in 1973, the year the average baby boomer was 18, and rates decreased as the baby boomers aged out of the high-risk age for acquiring infection.31 Changes in the number of reported cases have been influenced by changes in testing, sensitivity of tests, and reporting. Still, there is no doubt that the true incidence of gonorrhea is much lower now than it was in the 1970’s, and there is no doubt that rates of PID have fallen.37–41

What can we learn from the gonorrhea control program? The gonorrhea control program involved substantial federal funding which covered widespread screening of women for gonorrhea. Screening rates continue to be very high, but most testing is now done by private providers. NAATs for gonorrhea are often combined with tests for chlamydia, therefore most women who are tested for chlamydia are also tested for gonorrhea. Although the numbers of chlamydia tests performed are not nationally available, there were over 1 million positive chlamydia tests among women reported in 2014.1 If the prevalence of chlamydia among females tested was, for example, 6.7% (1 out of 15) then 15 million women were tested for chlamydia and gonorrhea, suggesting the testing rate was comparable to the gonorrhea testing rates of the 1970’s. However, the gonorrhea control program involved a major health department effort to notify, test, and treat partners. Partner treatment is an important aspect of treating STD because reinfection is common, and reinfection is often attributable to an untreated partner.48 Partner notification is still done by some health departments, but mostly in areas where resources permit because there are few cases of syphilis or HIV. As testing shifted to the private sector, the burden of partner notification has shifted to clinicians who have many other responsibilities. However, new opportunities are also available to facilitate partner treatment such as cell phones or e-mail for contacting partners, and patient delivered partner therapy to facilitate treatment.48 A recent study in STD clinics found partners could be effectively and confidentially notified via telephone, an approach that cost only $171 to identify and treat a new infection.49 Further work is needed to expand this simple, effective, and low-cost approach to other settings.

Gonorrhea remains frustratingly common in the United States. When the control program began, funding for gonorrhea control exceeded funding for syphilis, the only other venereal disease that had a prevention program. Now both gonorrhea and syphilis compete for attention with HIV, herpes, human papillomavirus, and chlamydia (the most common reportable infection). The emergence of antimicrobial resistant strains further threatens gonorrhea control efforts. However, some new developments make gonorrhea control easier than ever. Urine-based testing technologies facilitate testing for gonorrhea, and the test for gonorrhea has been combined with the test for chlamydia, so testing for gonorrhea remains high. Screening for gonorrhea is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force for sexually active women age 24 years and younger and in older women who are at increased risk for infection,50 and thus is covered under most insurance plans. Electronic case reporting by laboratories gives health departments the opportunity to count and follow-up on cases that may have previously gone unreported. The internet and cell phones can help providers communicate with infected persons and their partners to assure treatment and retesting. Patient delivered partner treatment is permitted in 39 states,51 and has been shown to reduce reinfection among patients compared to traditional counseling on partner treatment.48 Gonorrhea is not the national priority that it was in the 1970’s, but downward trends could resume if treating partners was considered an integral part of treating patients—and it is.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2014 Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farley TA, Cohen DA, Elkins W. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Preventive Medicine 2003;36:502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunham RC, Gottlieb SL, Paavonen J. Pelvic inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2039–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henderson RH. Venereal disease: a national health problem. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1975;18:223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidd S, Workowski KA. Management of gonorrhea in adolescents and adults in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61 (Suppl 8):S786–S801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thayer JD, Martin JE. A selective medium for the cultivation of N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitides. Public Health Rep 1964;79:49–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown WJ. Trends and status of gonorrhea in the United States. J Infect Dis 1971;123:683–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balows A, Printz DW. CDC program for diagnosis of gonorrhea (letter). JAMA 1972;222:1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zackler J, Brolnitsky O, Orbach H. Preliminary report on a mass program for detection of gonorrhea. Public Health Rep 1970;85:681–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart M Gonorrhea in women. JAMA 1971;216:1609–1611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinman AR. Evaluation of gonorrhea control efforts. J Am VD Assoc 1975;2:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleming WL, Brown WJ. National survey of venereal disease treated by physicians in 1968. JAMA 1970,211:1827–1830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. http://www.cdc.gov/std/infertility/ipp-archive.htm.

- 14.Pedersen AHB, Harrah WD . Followup of male and female contacts of patients with gonorrhea. Pub Health Rep 1970;85:997–1000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judson FN, Wolf FC. Tracing and treating contacts of gonorrhea patients in a clinic for sexually transmitted diseases. Pub Health Rep 1978;93:460–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handsfield HH, Lipman TO, Harnisch JP, Tronca E, Holmes KK. Asymptomatic gonorrhea in men. Diagnosis, natural course, prevalence and significance N Engl J Med 1974:290:117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilstrap LC III, Herbert WNP, Cunningham G, Hauth JC, Van Patten HG. Gonorrhea screening in male consorts of women with pelvic infection. JAMA 1977;238:965–966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips L, Potterat JJ, Rothenberg RB, Pratts C, King RD. Focused interviewing in gonorrhea control. Am J Pub Health 1980;70:705–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potterat JJ, King RD. A new approach to gonorrhea control: the asymptomatic man and incidence reduction. JAMA 1981;245:578–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potterat JJ, Rothenberg R. The case-finding effectiveness of a self-referral system for gonorrhea: a preliminary report. Am J Pub Health 1977;67:174–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brewer DD. Case-finding effectiveness of partner notification and cluster investigation for sexually transmitted diseases/HIV. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katz BP, Danos CS, Quinn TS, Caine V, Jones RB. Efficiency and cost-effectiveness of field follow-up for patients with chlamydia trachomatis infection in a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Sex Transm Dis 1988;15:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golden MR, Hogben M, Handsfield HH, St. Lawrence JS, Potterat JJ, Holmes KK. Partner notification for HIV and STD in the United States: low coverage for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, and HIV. Sex Transm Dis 2003;30:490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gale JL, Hinds MW. Male urethritis in King County, Washington, 1974–1975: I Incidence. Am J Public Health 1978;68:20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stiffman M, Carr P, Yokoe D, et al. Reporting of laboratory-confirmed chlamydial infection and gonorrhea by providers affiliated with three large managed care organizations---United States, 1995−−1999— MMWR 2002;51:256–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Overhage JM, Grannis S, McDonald CJ. A comparison of the completeness and timeliness of automated electronic laboratory reporting and spontaneous reporting of notifiable conditions. Am J Public Health 2008;98:344–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chow EPF, Fehler G, Read TRH, et al. Gonorrhoea notifications and nucleic acid amplification testing in a very low-prevalence Australian female population. Med J Aust 2015;202:321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papp JR, Schachter J, Gaydos CA, Van Der Pol B. Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae—2014. MMWR 2014;63(No. RR2):1–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Chlamydia screening in women. https://www.ncqa.org/ReportCards/HealthPlans/StateofHealthCareQuality/2015TableofContents/ChlamydiaScreening.aspx

- 31.Fox KK, Whittington WL, Levine WC, Moran JS, Zaidi AA, Nakashima AK. Gonorrhea in the United States, 1981–1996: demographic and geographic trends. Sex Transm Dis 1998;25:386–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaidi AA, Aral SO, Reynolds GH, Blount JH, Jones OG, Fichtner RR. Gonorrhea in the United States: 1967–1979. Sex Transm Dis 1983;10:72–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller WC, Ford CA, Morris M, et al. Prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among young adults in the United States. JAMA 2004;291:2229–2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torrone EA, Johnson RE, Tian LH, Papp JR, Datta SD, Weinstock HS. Prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae among persons 14 to 39 years of age, United States, 1999 to 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:202–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradley H, Satterwhite CL. Prevalence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections among men and women entering the National Job Training Program—United States, 2004–2009. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.CDC. Pelvic inflammatory disease: guidelines for prevention and management. MMWR 1991:40(RR-5);1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sutton MY, Sternberg M, Zaidi A, St. Louis ME, Markowitz LE. Trends in pelvic inflammatory disease hospital discharges and ambulatory visits, United States, 1985—2001. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:778–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bohm MK, Newman L, Satterwhite CL, Tao G, Weinstock HS. Pelvic inflammatory disease among privately insured women, United States, 2001–2005. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37:131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anschuetz GL, Asbel L, Spain CV, et al. Association between enhanced screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae and reductions in sequelae among women J Adolescent Health 2012;51:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scholes D, Satterwhite CL, Yu O, Fine D, Weinstock H, Berman S. Long-term trends in Chlamydia trachomatis infections and related outcomes in a US managed care population. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Aral SO. Correlates of self-reported pelvic inflammatory disease treatment in sexually experienced reproductive-aged women in the United States, 1995 and 2006–2010. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40:413–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darrow WW. Changes in sexual behavior and venereal diseases. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1975;18:255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. http://www.pewresearch.org/next-america/#Two-Dramas-in-Slow-Motion.

- 44.Piccinino LJ, Mosher WE. Trends in contraceptive use in the United States: 1982–1995. Family Planning Perspectives 1998;30:4–10 & 46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006–2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995 National Health Statistics Reports; no 60. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katz MH, Schwarcz SK, Kellogg TA, et al. Impact of highly actie antiretroviral treatment on HIV seroincidence among men who have sex with men: San Francisco. Am J Public Health 2002;92:388–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Declining rates of rectal and pharyngeal gonorrhea among males–New York City. MMWR 1984;33:295–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Althaus CL, Turner KME, Mercer CH, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of traditional and new partner notification technologies for curable sexually transmitted infections: observational study, systematic reviews and mathematical modelling. Health Technol Assess 2014;18(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahman MM, Khan M, Gruber D. A low-cost partner notification strategy for the control of sexually transmitted diseases: a case control study from Louisiana. Am J Public Health 2015;105:1675–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement Gonorrhea and chlamydia: screening, September 2014. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/chlamydia-and-gonorrhea-screening

- 51.CDC. Legal Status of Expedited Partner Therapy (EPT). http://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/

- 52.U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control. VD Fact Sheet, 1976. Edition Thirty-Three. HEW Publication No. (CDC) 77–8195. P 27. [Google Scholar]