Abstract

Introduction

Despite having severe Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology, some individuals remain cognitively asymptomatic (cASYM). To explore non-cognitive manifestations in these cASYM individuals, we aim to investigate the prevalence and pathological substrates of psychosis.

Methods

Data was obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire, quick version was used to evaluate presence of psychosis. Subjects with Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score of ≥24 with frequent neuritic plaques (NP) were defined as NPcASYM, and those with Braak&Braak (B&B) stage of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) of V/VI were defined as NTcASYM (both groups collectively designated cASYM). Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the association between NP and NFT severity and psychosis accounting for potential confounders.

Results

We identified 667 subjects with MMSE score of ≥24, of which 137 were NPcASYM and 96 were NTcASYM. NPcASYM were at significantly higher risk of having psychosis compared with those with moderate or sparse/no NP (OR, 2.47, 95% CI: 1.54–3.96). NTcASYM were also at higher risk compared to those with B&B stage I-IV, but the association explained by the effect of Lewy body pathology and microinfarcts.

Discussions

The load of NP may be important substrate of psychosis in individuals who show no gross cognitive symptoms.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Neuropathology, Cognitively Asymptomatic, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, Delusions, Hallucinations

Introduction

Clinicopathological studies indicate that the severity of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology is correlated with greater cognitive and functional decline [1-3], but there is an important discordance. The progressive accumulation of neuritic plaques (NP) and neurofibillary tangles (NFT) develops before clinical symptoms start to emerge [4, 5], but even with severe underlying AD pathology a significant number of individuals remain cognitively intact, reflecting resilience to the ravages of disease, [6, 7]. It is possible that these subjects manifest other manifestations of AD, including psychotic symptoms, preceding cognitive impairments.

Mild behavioural impairment (MBI) has been used in recent years to describe later-life manifestations of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) in the absence of cognitive deficits or in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [8]. MBI has been linked to increased risk of developing dementia [8]. Psychosis including both delusions and hallucinations are common and clinically distinct NPS of AD [9]. While previous studies have investigated psychosis in association with cognitive function [10, 11], the pathological correlates of psychosis in patients with MBI has not been investigated. Identification of NPS in the absence of cognitive decline or MCI may allow us to better differentiate the neurobiology of these common deficits.

The aim of the current study is to examine the substrate of psychotic symptoms in cognitively intact subjects with severe AD pathology, both NP and NFT. Furthermore, we seek to explore the role of other common pathologies including vascular lesions and Lewy body pathology in the clinical manifestation of psychosis among cognitively asymptomatic individuals.

Methods

Data Source

Data was obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC). The NACC encompasses data from 34 past and present Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADC). Both the uniform and neuropathology dataset collected between September 2005 and December 2015 were obtained for analysis. The UDS was used to collect demographic and clinical characteristics, and the neuropsychiatric profile based on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire, quick version (NPI-Q), which evaluates neuropsychiatric symptoms within the last month prior to clinical visit. It is important to note that the criteria for delusions on the NPI-Q is mainly persecutory delusions. The neuropathology dataset provided information on the density of NP and extent of NFT. The density of NP was classified as sparse, moderate, or frequent NP based on the CERAD criteria [12]. The NFT was classified based on Braak & Braak (B&B) stage of NFT, which include B&B stage I or II, B&B stage III or IV, and B&B stage V or VI [13]. The presence of vascular lesions, including absence or presence of microinfarcts, lacunes, and subcortical arteriosclerotic leukoencephalopathy were also obtained. Presence of lacunes was defined as having one or more lacunes (small artery infarcts and/or hemorrhages). Presence of Lewy body pathology was defined as having brainstem, transitional, including amygdala, or diffuse Lewy bodies [14]. Lewy bodies in the olfactory bulb or regions unspecified were not considered.

Subject Criteria

The time interval between last clinical visit and death was limited to two years. Subjects with symptoms of delusions or hallucinations at any point during the course of their illness were categorized as having psychosis. Delusions and hallucinations were not analyzed separately due to limited sample size.

Based on criteria reported in the current literature, subjects with Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) scores of 24 or above were categorized as being cognitively intact [15-17]. Within these groups, subjects with frequent neuritic plaques based on CERAD score of frequent neuritic plaques were classified as NPcASYM, and those with B&B stage V or VI were classified NTcASYM) (collectively cASYM). Each group was compared to cognitively intact subjects with absent/low or intermediate load of NP and NFT, respectively. The analyses were replicated using the global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score of 0 or 0.5 (i.e., no impairment or questionable impairment) (Supplemental Table 1).

Subjects with the following primary pathological diagnoses were excluded: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, prion disease, trinucleotide disease (i.e., Huntington disease, spinocerebellar ataxia, other), malformation of cortical development, white matter disease (i.e., multiple sclerosis or other demyelinating disease), neoplasm (primary and metastatic), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) with tau pathology.

Statistical Analysis

The relationship between variables was studied using descriptive statistics. For categorical data, the χ2 test was used. For continuous data, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality was first used to evaluate the normality. The independent sample t-test or Mann-Whitney test was used for data with normal or non-normal distribution respectively. The cASYMP group was analyzed with respect to the NP density (sparse, moderate or frequent) and the NFT category (dichotomized as: B&B stage I or II, B&B stage III or IV, and B&B stage V or VI). The relationship between NPcASYM or NTcASYM status and psychosis was investigated by fitting logistic regression models, sequentially adjusting for age, sex and educational status (Model B), the additional effect of presence of Lewy body pathology and microinfarcts (Model C); and the effect of AD pathology (Model D). The association is reported as Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The significance level was set at α=0.05.

Results

Subject Demographics

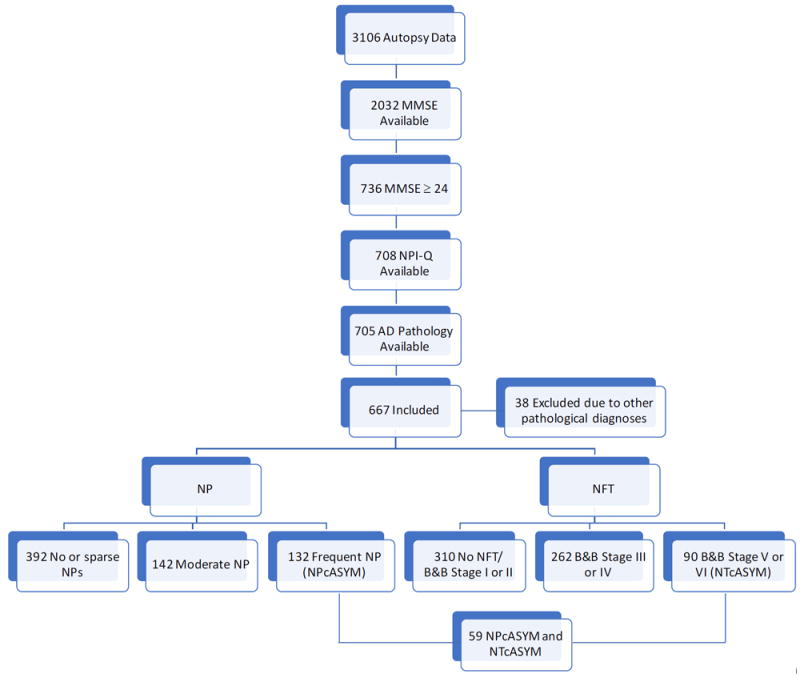

On the NACC database, 3835 subjects had autopsy data, and 3106 had autopsy performed within two years of last clinical visit. Of these subjects, 2032 had MMSE score available, of which 736 subjects had MMSE score of equal or greater than 24. Of 736 subjects, 708 had NPI-Q score available, and 3 were missing AD pathology data, and 38 were excluded due to other pathological diagnoses. In total, 667 subjects were included. Further categorization of subjects in different categories of AD pathology are displayed in Figure 1. Not all subjects with AD pathology data had record on vascular lesions (i.e., microinfarcts (n = 665), lacunes (n = 587), subcortical arteriosclerotic leukoencephalopathy (n = 586), Lewy body pathology (n = 646)).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included participants. MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NPI-Q, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire, quick version; NP, Neuritic plaques; NFT, Neurofibillary tangles

Table 1 compares the demographic and clinical characteristics of the cASYM group by NP density and NFT categories. An inverse relation was noted between MMSE score and NP density and NFT category, with lower MMSE score more likely with higher NP density or higher NFT category (p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| NP | NFT | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| No or Sparse NPs | Moderate NPs | Frequent NPs | No NFTs or B&B Stage I or II | B&B Stage III or IV | B&B Stage V or VI | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| N = 392 | N = 142 | N = 132 | N = 310 | N = 262 | N = 90 | |||||||

| N / Mean | % /SD | N / Mean | % /SD | N / Mean | % /SD | N / Mean | % /SD | N / Mean | % /SD | N / Mean | % /SD | |

| Age at Last Clinical Visit | 82.36 | 11.17 | 85.35 * | 8.65 | 82.72 | 8.61 | 79.73 | 11.32 | 86.76 * | 7.79 | 83.53 * | 9.15 |

| Age at Death | 83.23 | 11.14 | 86.10 * | 8.59 | 83.59 | 8.53 | 80.60 | 11.32 | 87.57 * | 7.68 | 84.39 * | 9.09 |

| Interval Between Last Clinical Visit and Death | 10.26 | 5.78 | 9.71 | 5.76 | 10.52 | 5.68 | 10.25 | 5.96 | 10.24 | 5.71 | 10.24 | 5.33 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 199 | 51% | 84 | 59% | 71 | 54% | 172 | 55% | 128 | 48% | 54 | 60% |

| Education (Years) | 15.48 | 2.73 | 15.84 | 3.02 | 16.01 | 3.02 | 15.69 | 2.76 | 15.40 | 2.96 | 16.40 | 2.81 |

| MMSE Score | 27.61 | 1.86 | 27.14 | 1.88 | 26.73 * | 1.92 | 27.74 | 1.91 | 27.24 * | 1.82 | 26.28 * | 1.92 |

NP, neuritic plaques; NFT, neurofibrillary tangles; B&B stage, Braak and Braak stage of NFT; MMSE, mini mental state examination.

Moderate and frequent NP group was independently analyzed against no or sparse NP. B&B stage III or IV or stage V or VI group was independently analyzed against no NFT or stage I or II.

p ≤0.005, Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Psychosis in Cognitively Asymptomatic Subjects

Table 2 shows the distribution of the severity of AD pathology, vascular lesions, and Lewy body pathology according to psychosis status. Although not included in the analysis, the sample size for subjects with both delusions and hallucinations are also shown. The percentage distribution of psychotic subjects was highest in the category with frequent NP compared to the category with moderate or spare/no NP (20% vs. 8% vs. 10%, p < 0.05). The differences between psychotic and non-psychotic subjects in the distribution of NFT, microinfarcts, lacunes, subcortical arteriosclerotic leukoencephalopathy, and Lewy body pathology did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Distribution psychosis and severity of Alzheimer’s disease pathology, vascular lesions, and Lewy body pathology.

| Never Psychotic | Psychotic | Delusions | Hallucinations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| NP | ||||||||

| No or Sparse NP | 353 | 90% | 39 | 10% | 30 | 8% | 18 | 5% |

| Moderate NP | 131 | 92% | 11 | 8% | 7 | 5% | 4 | 3% |

| Frequent NP | 106 | 80% | 26 | 20% | 22 | 17% | 9 | 8% |

| NFT | ||||||||

| No NFT or B&B Stage I or II | 280 | 90% | 30 | 10% | 22 | 7% | 13 | 4% |

| B&B Stage III or IV | 231 | 88% | 31 | 12% | 25 | 10% | 12 | 5% |

| B&B Stage V or VI | 75 | 83% | 15 | 17% | 12 | 14% | 6 | 7% |

| Microinfarcts | ||||||||

| Absent | 459 | 89% | 59 | 11% | 45 | 9% | 23 | 5% |

| Present | 132 | 89% | 17 | 11% | 14 | 10% | 8 | 6% |

| Lacunes | ||||||||

| Absent | 435 | 90% | 47 | 10% | 37 | 8% | 18 | 4% |

| Present | 95 | 87% | 14 | 13% | 11 | 10% | 6 | 6% |

| Subcortical arteriosclerotic leukoencephalopathy | ||||||||

| Absent | 25 | 86% | 4 | 14% | 3 | 11% | 2 | 7% |

| Present | 33 | 77% | 10 | 23% | 7 | 18% | 4 | 11% |

| Lewy Body Pathologies | ||||||||

| Absent | 476 | 90% | 54 | 10% | 42 | 8% | 18 | 4% |

| Present | 98 | 84% | 19 | 16% | 14 | 13% | 12 | 11% |

NP, neuritic plaques; NFT, neurofibrillary tangles; B&B stage, Braak and Braak stage of NFT.

Table 3 shows the results from the regression analysis. In unadjusted analysis (Model A), NPcASYM were at significantly higher risk of having psychosis, compared with those with moderate or sparse/no NP (OR, 2.47, 95% CI: 1.54 – 3.96). Adjusting for clinical confounders had marginal impact on the strength of the association (OR, 2.55, 95% CI: 1.58 – 4.11). Further adjustment for Lewy body pathology and microinfarcts had a slight effect on the association with the OR reduced from 2.55 to 2.26. Adjusting for the additional effect of B&B stage, reduced the OR to 2.13, 95% CI: 1.09 – 4.17. In the unadjusted analysis, NTcASYM were at significantly higher risk of psychosis compared to their counterparts who were B&B stage I-III (OR, 1.88, 95% CI: 1.05 – 3.38). Adjusting for demographic confounders had no effect on the strength of the association (OR, 1.89, 95% CI: 1.05 – 3.42). However, further adjustment for Lewy body pathology and microinfarcts resulted to a loss of the association (OR, 1.75, 95% CI: 0.87 – 3.52).

Table 3.

Results of regression analysis of the relationship between AD pathology and psychosis in cognitively asymptomatic subjects

| Predictor | Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPcASYM | ||||

| No | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 2.47 (1.54 – 3.96) | 2.55 (1.58 – 4.11) | 2.26 (1.25 – 4.08) | 2.13 (1.09 – 4.17) |

| NTcASYM | ||||

| No | ||||

| Yes | 1.88 (1.05 – 3.38) | 1.89 (1.05 – 3.42) | 1.75 (0.87 – 3.52) | 1.16 (0.52 – 2.58) |

Model A: Unadjusted effect

Model B: Adjusted for Age, Sex and years of education

Model C: Model B + Lewy body, microinfarcts

Model D: Model C + B&B stage (for NPcASYM effect analsysis) or (NP frequency for NTcASYM effect analysis)

Discussion

Clinicopathological studies investigating the correlation between AD pathology and cognitive status demonstrated a differential effect of NFT and NP. NFT have been identified as prominent indicator of cognitive decline [18-20]. Findings from the present study suggest that NP may be important predictors of non-cognitive clinical manifestations, specifically psychosis. The association between NP and psychosis was independent of demographic factors, vascular pathology, and the severity of NFT. Vascular lesions have been previously identified as a major risk factor for psychosis in AD through clinicopathological and neuroimaging studies [21-23]. Furthermore, Lewy body pathology is a known risk factor for hallucinations [24]. The results of our study did not show an independent association between vascular lesions and Lewy bodies on psychosis. While an association between NFT and psychosis was observed, this association was dependent on effect of vascular lesions and Lewy bodies. However, as our study was cross-sectional, further longitudinal studies may allow for better differentiate the role of NFT, vascular lesions, and Lewy bodies in the manifestation of psychosis. Furthermore, while a significant correlation was found between the MMSE scores in cASYM subjects with severe compared to mild AD pathology, the difference in the scores are clinically negligible.

The present study has several limitations. First of all, delusions and hallucinations were not analyzed separately due to limited sample size. As previous studies have suggested different neurobiology behind delusions and hallucination, further studies are needed to investigate whether NP have differential effect on inducing delusions and hallucinations in cognitively intact subjects [25]. Another important limitation is that we used an arbitrary cut-off MMSE score of 24 to define cognitively intact subjects. This cut-off is considered clinically appropriate and has been frequently used in previous studies, but does not capture subtle cognitive deficits. [15-17]. Therefore, our subject sample does not exclude MCI. Also, missing data might have caused attrition bias, potentially confounding our results. Further studies using a more extensive cognitive examination and complete data on AD pathology is needed to confirm our findings.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that in cognitively asymptomatic subjects, AD pathology specifically the severity of NP is associated with higher risk of psychosis. Going forward, longitudinal studies examining the progression of NP and other risk factors may be needed to better understand the neurobiology leading to the divergence in clinical manifestations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [Grant number 313912]. The NACC data are contributed by the NIAfunded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI Marie-Francoise Chesselet, MD, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bancher C, et al. Correlations between mental state and quantitative neuropathology in the Vienna Longitudinal Study on Dementia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;246(3):137–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02189115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xuereb JH, et al. Neuropathological findings in the very old. Results from the first 101 brains of a population-based longitudinal study of dementing disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;903:490–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson PT, et al. Clinicopathologic correlations in a large Alzheimer disease center autopsy cohort: neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles “do count” when staging disease severity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(12):1136–46. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31815c5efb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godbolt AK, et al. The natural history of Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal presymptomatic and symptomatic study of a familial cohort. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(11):1743–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.11.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thal DR, Braak H. Post-mortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Pathologe. 2005;26(3):201–13. doi: 10.1007/s00292-004-0695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ewbank DC, Arnold SE. Cool with plaques and tangles. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(22):2357–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0901965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien RJ, et al. Neuropathologic studies of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18(3):665–75. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ismail Z, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as early manifestations of emergent dementia: Provisional diagnostic criteria for mild behavioral impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ropacki SA, Jeste DV. Epidemiology of and Risk Factors for Psychosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of 55 Studies Published From 1990 to 2003. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):2022–2030. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeste DV, et al. Cognitive deficits of patients with Alzheimer’s disease with and without delusions. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(2):184–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koppel J, et al. Psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with frontal metabolic impairment and accelerated decline in working memory: findings from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(7):698–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirra SS, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41(4):479–86. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82(4):239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKeith IG, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65(12):1863–72. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(9):922–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lancu I, Olmer A. The minimental state examination--an up-to-date review. Harefuah. 2006;145(9):687–90, 701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchell AJ. A meta-analysis of the accuracy of the mini-mental state examination in the detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(4):411–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monsell SE, et al. Comparison of symptomatic and asymptomatic persons with Alzheimer disease neuropathology. Neurology. 2013;80(23):2121–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318295d7a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghoshal N, et al. Tau conformational changes correspond to impairments of episodic memory in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2002;177(2):475–93. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han SD, et al. Beta amyloid, tau, neuroimaging, and cognition: sequence modeling of biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Imaging Behav. 2012;6(4):610–20. doi: 10.1007/s11682-012-9177-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Youn JC, et al. White Matter Changes Associated With Psychotic Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2006;18(2):191–198. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2006.18.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fischer CE, et al. Lewy Bodies, Vascular Risk Factors, and Subcortical Arteriosclerotic Leukoencephalopathy, but not Alzheimer Pathology, are Associated with Development of Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2015;50(1):283. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, et al. The Role of Cerebrovascular Disease on Cognitive and Functional Status and Psychosis in Severe Alzheimer’s Disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2016;55(1):381–389. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Ser T, et al. Clinical and pathologic features of two groups of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies: effect of coexisting Alzheimer-type lesion load. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15(1):31–44. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ismail Z, et al. Neurobiology of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):211–8. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.