Abstract

BACKGROUND

We previously reported that a single injection of ketamine prior to stress protects against the onset of depressive-like behavior and attenuates learned fear. However, the molecular pathways and brain circuits underlying ketamine-induced stress resilience are still largely unknown.

METHODS

Here, we tested if prophylactic ketamine administration altered neural activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and/or hippocampus (HPC). Mice were injected with saline or ketamine (30 mg/kg) one week before social defeat (SD). Following behavioral tests assessing depressive-like behavior, mice were sacrificed and brains were processed to quantify ΔFosB expression. In a second set of experiments, mice were stereotaxically injected with viral vectors into ventral CA3 (vCA3) in order to silence or overexpress ΔFosB prior to prophylactic ketamine administration. In a third set of experiments, ArcCreERT2 mice, a line that allows for the indelible labeling of neural ensembles activated by a single experience, were used to quantify memory traces representing a contextual fear conditioning (CFC) experience following prophylactic ketamine administration.

RESULTS

Prophylactic ketamine administration increased ΔFosB expression in the ventral dentate gyrus (vDG) and vCA3 of SD mice but not of Ctrl mice. Transcriptional silencing of ΔFosB activity in vCA3 inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy, while overexpression of ΔFosB mimicked and occluded ketamine’s prophylactic effects. In the ArcCreERT2 mice, ketamine administration altered memory traces representing the CFC experience in vCA3, but not in vDG.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data indicate that prophylactic ketamine may be protective against a stressor by altering neural activity, specifically the neural ensembles representing an individual stressor in vCA3.

Keywords: Arc, hippocampus, ketamine, prefrontal cortex, deltaFosB, stress

INTRODUCTION

Stress is a primary cause of mood disorders such as major depressive disorder (MDD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1, 2). However, not all individuals respond similarly to stress. While some are stress-resilient, defined as the ability to adapt successfully to stress, others are susceptible to succumbing to pathological states in the face of a stressor. Although extensive research has focused on susceptibility and on pharmacological treatments that may counteract stress-related pathologies, few studies have investigated whether pharmacological treatments could increase stress resilience, thereby, preventing stress-induced mental illness.

The identification of the molecular pathways underlying stress resilience could inform the development of novel preventative approaches. In line with this notion, we recently reported that (R,S)-ketamine could protect against stress-induced depressive-like behavior (3) and attenuate learned fear (4) when administered 1 week before a stressor. Prophylactic ketamine efficacy has been replicated by two separate laboratories (5, 6), indicating the effectiveness of a preventative therapy. These findings suggest that pharmacological interventions may be able to enhance stress resilience and protect against stress-induced psychiatric disorders (e.g., PTSD and depression) in a long-lasting, self-maintaining vaccine-like fashion. Although this idea offers a new approach to protecting at-risk populations against stress-induced pathology, the mechanisms underlying ketamine-induced stress resilience remain still unknown.

Several works have implicated a series of mechanisms, including ΔFosB expression in the PFC and striatum (7, 8, 9) in the neurobiology of stress resilience. ΔFosB is a transcription factor within the Fos family that is known to regulate synaptic plasticity in brain reward regions. It is stably induced by chronic stimuli, such as repeated stress, chronic antidepressant treatment, and repeated administration of drugs of abuse (10). High ΔFosB expression is correlated with resilience and low ΔFosB expression with susceptibility (11). Most importantly, while the induction of most Fos family proteins is transient, ΔFosB has a half-life of 8 days in vivo, making it an ideal candidate mechanism for long-term changes in gene expression.

In this study, in order to better understand the mechanisms underlying ketamine-induced stress resilience, mice were injected with saline or ketamine 1 week before SD. Mice were then sacrificed and brains were processed for ΔFosB expression. We hypothesized that ketamine would alter ΔFosB expression in the vHPC, but not dHPC, as recent data has shown a fundamental link between stress, psychiatric diseases, and changes in vHPC, while the dorsal HPC (dHPC) is responsible for cognitive function (12, 13). We found that prophylactic ketamine, but not SD, increased ΔFosB expression in the PFC, specifically the infralimbic cortex (IL), prelimbic cortex (PL), and anterior cingulate (CgL). However, in the HPC, prophylactic ketamine increased ΔFosB expression in the vDG and vCA3 only in the SD group. Interestingly, transcriptional silencing of ΔFosB activity in vCA3 inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy, while overexpression of ΔFosB mimicked and occluded ketamine’s effects on stress-induced depressive-like behavior. In the ArcCreERT2 mice, we found that ketamine administration altered memory traces representing the stressful experience in vCA3, but not in vDG. These data indicate that ketamine administration may protect against the induction of stress-related disorders by altering neural activity in vCA3. By understanding how ketamine affects neuronal populations, this work will elucidate an important mechanism of action and point to potential novel therapeutic targets.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Mice

SD and Viral Studies: Male 129S6/SvEvTac male mice were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, New York) and housed 4–5 per cage in a 12-h (06:00– 18:00) light–dark colony room at 22°C. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All behavioral testing was performed during the light phase. All the procedures described herein were conducted in compliance with the NIH regulations and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Memory Trace Studies: ArcCreERT2 (+) female mice (14) were bred with Rosa26-CAG-stopflox- channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) (H134R)-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) (Ai32) male mice (15). All experimental mice were heterozygous for the reporter.

(R,S)-Ketamine

A single injection of saline (0.9% NaCl) or ketamine (30 mg kg-1) (Ketaset III, Ketamine HCl injection, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Fort Dodge, Iowa) was administered 1 week before the start of SD or CFC according to our previous studies (3, 4).

4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT)

4-OHT (2 mg, H7904, Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) was prepared as previously described (16).

Social Defeat (SD)

SD was performed as previously described (3). Brains in Figures 1 and 2 were processed from the SD cohorts published in (3).

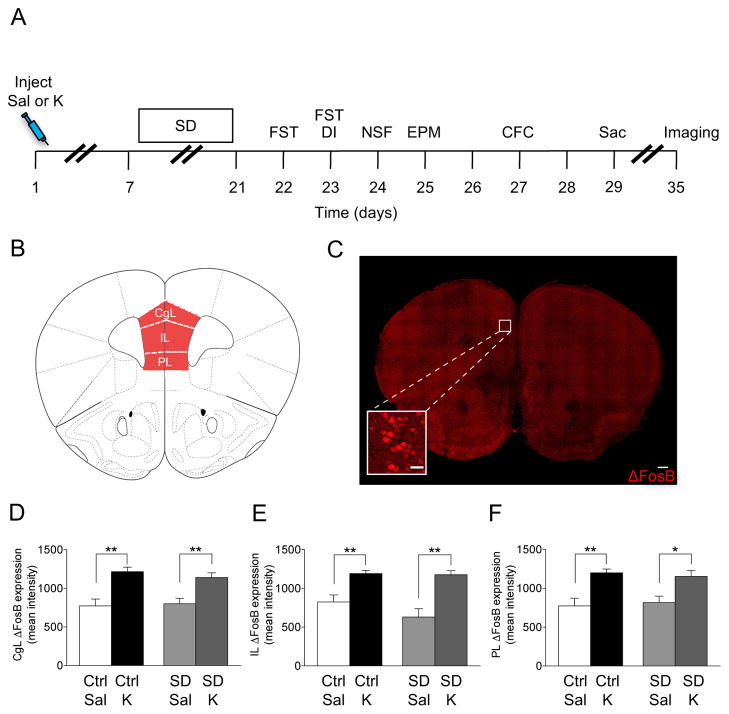

Figure 1.

Ketamine, but not SD stress increases ΔFosB expression in the PFC. (A) Experimental timeline. (B) Coronal figure (modified from Paxinos and Franklin, 2012) showing PFC regions. (C) Confocal image showing ΔFosB expression in the PFC. Scale bar: 250 μm and 25 μm (inset). Ketamine, but not SD increases ΔFosB expression in the (D) CgL, (E) IL, and (F) PL subregions of the PFC. (n = 4–7 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; Ctrl, control; SD, social defeat; FST, forced swim test; DI, dominant interaction; NSF, novelty suppressed feeding; EPM, elevated plus maze; CFC, contextual fear conditioning; Sac, sacrifice; PFC, prefrontal cortex; CgL, cingulate; IL, infralimbic; PL, prelimbic.

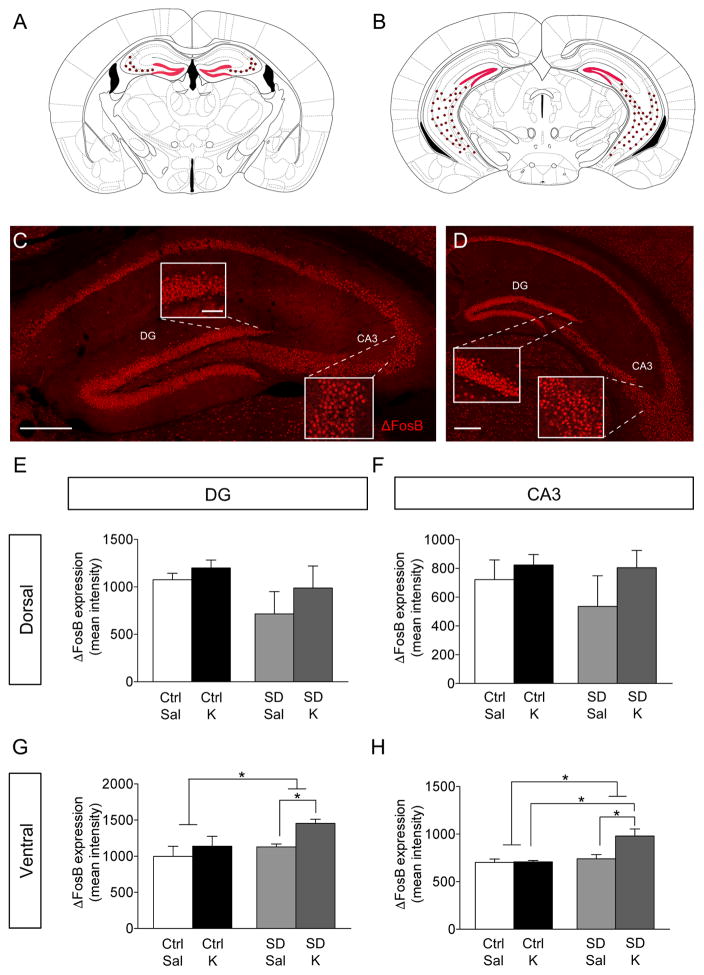

Figure 2.

Ketamine selectively increases ΔFosB expression in the vHPC in SD mice. (A–B) Coronal figures (modified from Paxinos and Franklin, 2012) showing dHPC and vHPC. ΔFosB expression in the (C) dHPC and (D) vHPC. Scale bar: 250 μm and 25 μm (inset). Ketamine and SD does not alter ΔFosB expression in the dorsal (E) DG and (F) CA3. However, prophylactic ketamine increases ΔFosB expression in the dorsal (G) DG and (H) CA3 in SD mice, but not in Ctrl mice. (n = 4–7 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; Ctrl, control; SD, social defeat; DG, dentate gyrus; CA3, Cornu Ammonis region 3.

Contextual Fear Conditioning (CFC)

A 3-shock CFC paradigm was administered as previously described (16, 17).

Forced Swim Test (FST)

The FST was administered as previously described (3).

Viral Injections

Viral constructs were injected as previously described (18), with some modifications. Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane in an O2/N2O (30%/70%) mixture and. Thirty-gauge needles were bilaterally placed at the following coordinates: −2.80 mm AP, ±3.0 mm ML, and −3.5 mm DV. Purified high-titer virus (0.6 μl) were infused separately (0.5 μl/infusion) over 5 min periods. Viral vectors included the following: adeno-associated virus (AAV2) expressing GFP (AAV–GFP), GFP and ΔFosB (AAV–ΔFosB), or GFP and ΔJunD (AAV–ΔJunD). The CMV promoter was used to drive expression. AAVs were obtained from the Robinson laboratory or the UNC Vector Core.

Immunohistochemistry

For ΔFosB, sections were washed 3 times in 1X PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and then were blocked in 2% normal donkey serum (NDS) in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 (0.3% PBST) for 2 h at room temperature (RT). Incubation with primary antibody was performed at 4°C for 48 h (rabbit anti-FosB, sc-48, 1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California) in 0.3% PBST. Sections were washed in 0.1% PBST and then incubated in secondary antibody (donkey anti-rabbit Cy3; 1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pennsylvania) for 2 h at RT.

For c-fos and EYFP, sections were washed 3 times in 1X PBS and then cleared using Reagent-1A:dH2O (1:2) (19) for 30 min followed by 2 h of clearing in Reagent-1A at 37°C. Sections were then washed 3 times in 1X PBS and blocked in 0.3% PBST and 10% NDS for 45 min at RT. Incubation with primary antibodies was performed at 4°C for 3 days (rabbit anti-c-fos, 226003, 1:5,000, SySy, Göttingen, Germany; chicken anti-GFP, ab13970, 1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, Massachusetts) in 0.3% PBST. Sections were washed 3 times in 1X PBS, and blocked in 0.3% PBST and 2% NDS for 1 h at RT. Sections were then incubated with secondary antibodies (donkey anti-chicken Cy2, 703225155, 1:500, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pennsylvania; donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 647, a31573, 1:500, Life Technologies, Guilford, Connecticut) for 2 h at RT.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using StatView 5.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) or Prism 5.0a (Graphpad Software, Inc., La Jolla, California). Alpha was set to 0.05 for all analyses. All statistical tests and p values are listed in Supplemental Table S01.

RESULTS

Prophylactic Ketamine Administration Increases ΔFosB Expression in the PFC

A variety of stimuli have been reported to induce ΔFosB in many brain regions, including the HPC and the PFC (7, 18, 20), but it is unknown whether prophylactic ketamine administration induces alterations in ΔFosB in these regions. Therefore, here, 129S6/SvEv mice were injected with saline or ketamine (30 mg/kg) 1 week before a SD paradigm. Following behavioral testing, mice were euthanized and brains were processed (Figure 1A). In this cohort, we previously reported that prophylactic ketamine administration prevented stress-induced depressive-like behavior (3).

In the PFC, there was an effect of Drug, but not of Group on ΔFosB expression (Figure 1B, C). Prophylactic ketamine administration significantly increased ΔFosB expression in the Cgl, IL, and PL regions in both control (Ctrl) and SD mice (Figure 1D, E, F, respectively). These data indicate that ΔFosB expression in the PFC increases following ketamine administration, but not following stress.

Prophylactic Ketamine Administration Increases ΔFosB Expression in the Ventral, but Not Dorsal HPC of Stressed Mice

We next determined whether there was a separate brain region that might be contributing to prophylactic ketamine’s effects. Here, we quantified ΔFosB expression in the HPC (Figure 2A, B, C, D). We found no effect of Group or Drug in the dorsal DG (dDG) (Figure 2E) or CA3 (Figure 2F). However, there was a significant effect of Group and of Drug in the vDG (Figure 2G). In SD mice, prophylactic ketamine administration increased ΔFosB expression in the vDG. In vCA3, again there was a significant effect of Drug and of Group (Figure 2H). Prophylactic ketamine administration increased ΔFosB expression in vCA3. These data indicate that prophylactic ketamine may be protective against SD by altering neural ensembles specifically in the ventral HPC (vHPC).

Transcriptional Silencing of ΔFosB Expression in vCA3 Occludes Prophylactic Ketamine Efficacy

By building on our previous findings that SD mice show less fear memory reactivation in vCA3 and altered CA3 neural ensembles, rather than in the DG (14), and on our evidence that ketamine induces ΔFosB alterations in vCA3 (Figure 2H), we hypothesized that silencing ΔFosB-mediated activator protein-1 transcriptional activity in vCA3, by using adenoviral ΔJunD expression, would block ketamine’s prophylactic effect on stress-induced depressive-like behavior (3) and attenuate learned fear (4). Mice were injected with AAV–GFP or AAV–ΔJunD viruses into vCA3 2 weeks before a single injection of saline or ketamine (30 mg/kg) (Figure 3A). After 1 week, mice were administered 3-shock CFC and a number of behavioral assays. CFC rather than SD was utilized here since there is a fixed temporal window for acquisition of a stressor. Following CFC, mice were euthanized and brains were processed for GFP and ΔFosB immunofluorescence to confirm viral targeting (Figure 3B, C)

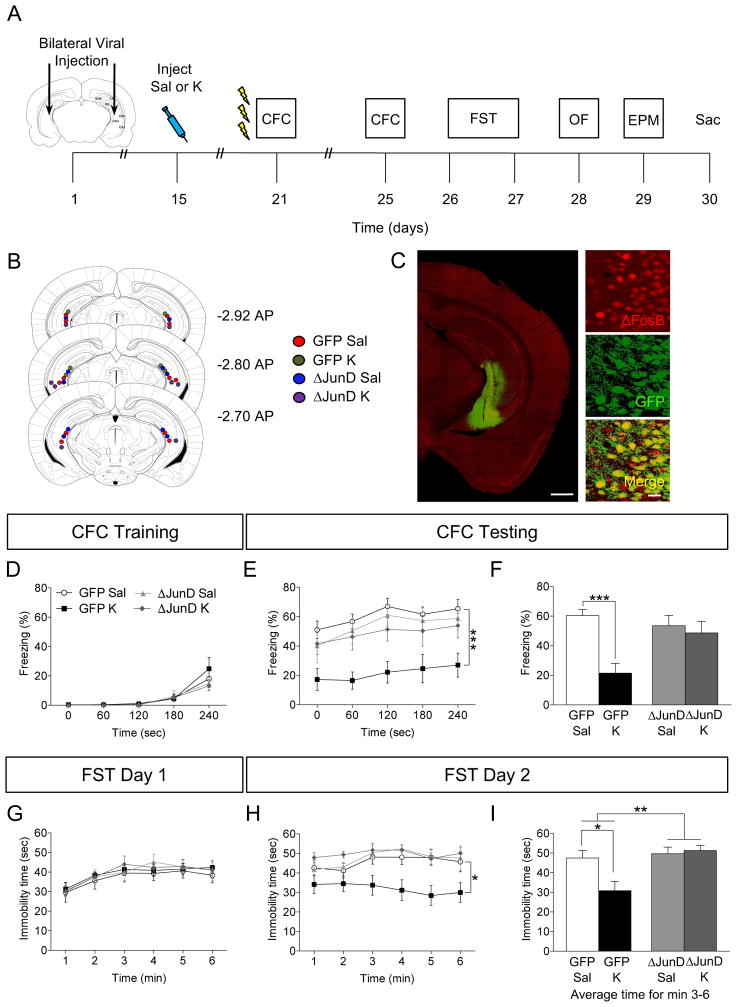

Figure 3.

Viral blockade of ΔFosB expression inhibits prophylactic efficacy of ketamine. (A) Experimental timeline. (B) Coronal figures (Paxinos and Franklin, 2012) showing viral injection sites in vCA3. (C) GFP and ΔFosB expression following viral injection Scale bar: 500 μm and 25 μm (inset). (D) All groups of mice had comparable freezing during CFC encoding. (E–F) Prophylactic ketamine GFP mice exhibited attenuated fear when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. However, blockade of ΔFosB expression with ΔJunD inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy. (G) On day 1 of the FST, all groups of mice had comparable immobility. (H) On day 2 of the FST, prophylactic ketamine GFP mice exhibited decreased immobility when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. Blockade of ΔFosB expression with ΔJunD inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy. (I) On day 2 of the FST, average immobility time was reduced in the prophylactic ketamine GFP mice when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. Blockade of ΔFosB transcriptional activity with ΔJunD inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy. (n = 8 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; CFC, contextual fear conditioning; FST, forced swim test; OF, open field; EPM, elevated plus maze; Sac, sacrifice; GFP, green fluorescent protein; sec, seconds; min, minutes.

All groups of mice exhibited comparable levels of freezing during CFC training (Figure 3D). However, during CFC context exposure, there was no effect of Virus, but a significant effect of Drug and a Virus x Drug interaction on freezing (Figure 3E, F). In virally-injected GFP mice, prophylactic ketamine administration significantly decreased freezing in accordance with our previously published data using 3-shock CFC (4). However, viral injections of ΔJunD into vCA3 blocked prophylactic ketamine efficacy on attenuating learned fear, suggesting that transcriptional ΔFosB activity in vCA3 is necessary for prophylactic ketamine efficacy.

To determine if ΔFosB expression was necessary for ketamine-induced resilience to depressive-like behavior, we next administered the FST. We found no differences between groups in immobility time on day 1 (Figure 3G). On day 2 of the FST, in the GFP mice, ketamine significantly decreased immobility time (Figure 3H, I). In the ΔJunD mice, ketamine administration did not significantly alter immobility time when compared with saline administration. These data suggest once again that silencing ΔFosB activity in vCA3 blocks ketamine’s effect on depressive-like behavior.

We next examined the effect of ΔFosB silencing of transcriptional activity on anxiety-like behavior (Supplemental Figure S1A). Mice were tested in an OF to exclude any effects on locomotor activity. There were no significant differences between the groups on total basic movements. Mice were then tested in the EPM (Supplemental Figure S1B). There was no significant effect of Drug or Virus, but there was a significant Drug x Virus interaction on time spent in the closed arms. In the GFP mice, ketamine administration decreased time spent in the closed arms. In the ΔJunD mice, ketamine administration did not significantly alter time spent in the closed arms. These data are in disagreement with our previous studies showing no attenuation of anxiety-like behavior following a stressor (3, 4). Therefore, it remains to be defined if ketamine is as robust an anxiolytic as it is an antidepressant.

ΔFosB Overexpression in vCA3 Mimics and Occludes Prophylactic Ketamine Efficacy

We next examined if viral overexpression of ΔFosB in vCA3 could mimic ketamine’s prophylactic efficacy. Here, mice were injected with AAV–GFP or AAV–ΔFosB (Figure 4A). Following behavioral administration, brains were processed as aforementioned (Figure 4B, C). During CFC training, all groups froze comparably (Figure 4D). During CFC testing, there was a significant effect of Drug, Virus, and a significant Virus x Drug interaction on freezing behavior (Figure 4E, F). In virally-injected GFP mice, ketamine administration attenuated learned fear. In virally-injected ΔFosB mice, both saline and ketamine administration resulted in low levels of freezing, comparable to saline-injected GFP mice. These results are in agreement with previous data showing that ΔFosB overexpression reduces freezing levels (18) and indicates that ΔFosB overexpression mimics ketamine’s prophylactic efficacy for attenuating learned fear.

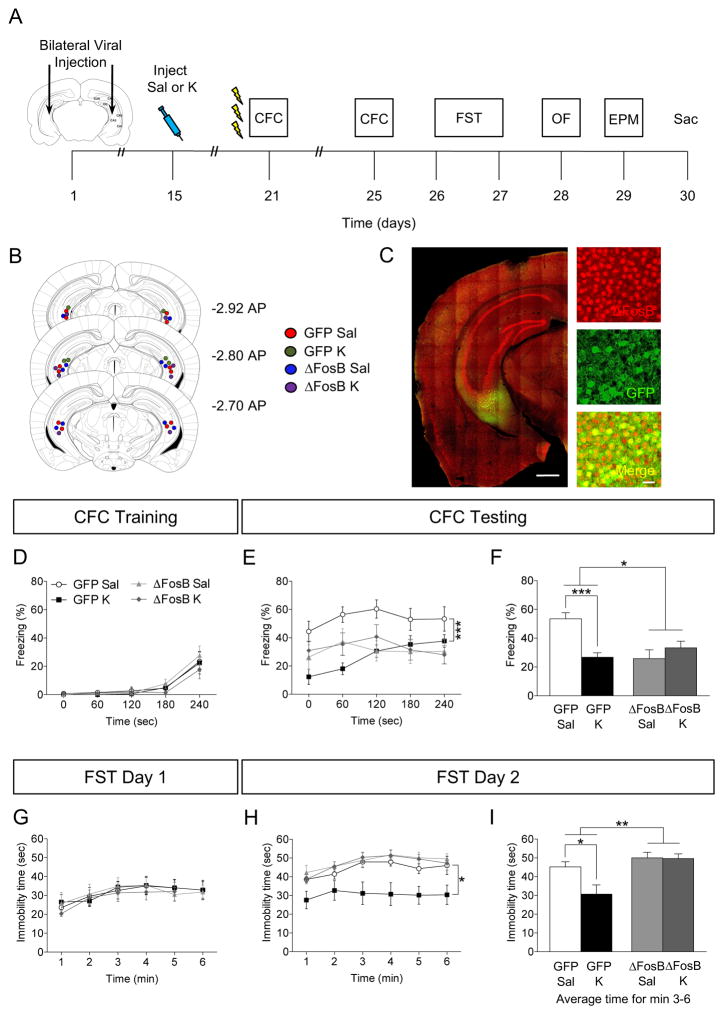

Figure 4.

Viral overexpression of ΔFosB mimics prophylactic efficacy of ketamine in attenuating fear. (A) Experimental timeline. (B) Coronal figures (Paxinos and Franklin, 2012) showing viral injection site in vCA3. (C) GFP and ΔFosB expression following viral injection. Scale bar: 500 μm and 25 μm (inset). All groups of mice had comparable freezing during CFC encoding. (D–F) Prophylactic ketamine GFP mice exhibited attenuated fear when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. However, overexpression of ΔFosB with ΔFosB mimicked and occluded prophylactic ketamine efficacy in both ΔFosB groups. (G) On day 1 of the FST, all groups of mice had comparable immobility. (H) On day 2 of the FST, prophylactic ketamine GFP mice exhibited decreased immobility when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. Overexpression of ΔFosB inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy. (I) On day 2 of the FST, average immobility time was reduced in the prophylactic ketamine GFP mice when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. Overexpression of ΔFosB inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy. (n = 7–9 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; CFC, contextual fear conditioning; FST, forced swim test; GFP, green fluorescent protein; sec, seconds; min, minutes.

On day 1 of the FST, all groups of mice exhibited comparable immobility time (Figure 4G). On day 2 of the FST, in virally-injected GFP mice, ketamine administration significantly decreased immobility time (Figure 4H, I). However, ΔFosB overexpression occluded ketamine’s effect on immobility time. These data indicate that while ΔFosB overexpression mimics prophylactic ketamine’s efficacy in attenuating learned fear, it does not mimic ketamine’s efficacy in preventing stress-induced depressive-like behavior.

In the OF test, all groups of mice showed comparable locomotor activity (Supplemental Figure S1C). In the EPM test, there was a significant effect of Drug, Virus, and a significant Drug x Virus interaction on time spent in the closed arms. In virally-injected GFP mice, ketamine administration decreased time in the closed arms. However, overexpression of ΔFosB occluded ketamine’s efficacy and exacerbated the anxiogenic phenotype, in accordance with a previous a study (18).

In order to validate viral efficacy in both ΔFosB experiments, ΔFosB expression was quantified in vCA3 following viral injections (Supplemental Figure S02). Ketamine increased ΔFosB expression in GFP-injected mice. Ketamine did not alter ΔFosB expression in ΔJunD-injected mice as expected. Mice injected with ΔFosB virus had increased ΔFosB expression in vCA3 and prophylactic ketamine further increased ΔFosB expression in these mice. These data indicate that viral manipulations were targeted and specific to vCA3.

Prophylactic Ketamine Alters Stress Memory Traces in vCA3

Although prophylactic ketamine is efficacious at attenuating learned fear and preventing stress-induced depressive-like behavior, we have yet to determine what ketamine administration does to neural ensemble activity representing a stressor. Here, we utilized the ArcCreERT2 mice in order to assay if prophylactic ketamine administration changes the memory trace of the CFC experience (Figure 5A). Since ΔFosB expression was significantly altered in the HPC, we focused our studies on the DG and CA3 along the dorsoventral axis. ArcCreERT2 x ChR2-EYFP mice were injected with saline or ketamine. On week later, mice were injected with 4-OHT and administered 3-shock CFC 5 h later in order to indelibly tag the neural ensembles activated during fear encoding (Figure 5B). Five days later, mice were re-exposed to the aversive context and euthanized 1 h later in order to assay activity during fear expression. As previously reported (4), all groups of mice froze comparably during memory encoding (Figure 5C). Prophylactic ketamine administration resulted in an attenuated fear response (Figure 5D).

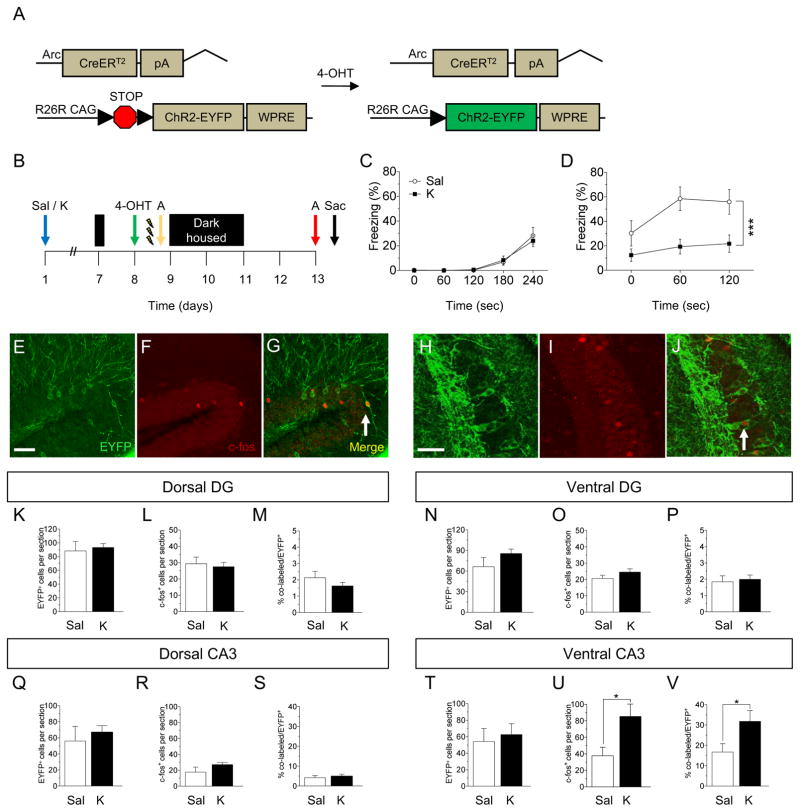

Figure 5.

Prophylactic ketamine alters stress memory traces in vCA3, but not dCA3. (A) Genetic design. (B) Experimental design. (C) EYFP, (D) c-fos, and (E) co-localized EYFP/c-fos expression in CA3 of ArcCreERT2 x ChR2-EYFP mice. Prophylactic ketamine administration did not alter the number of (D) EYFP+, (E) c-fos+, or (F) the percent of (EYFP+/c-fos+)/EYFP+ cells in the dDG or the number of (G) EYFP+, (H) c-fos+, or (I) the percent of (EYFP+/c-fos+)/EYFP+ cells in the vDG when compared with prophylactic saline administration. Prophylactic ketamine administration did not alter the number of (J) EYFP+, (K) c-fos+, or (L) the percent of (EYFP+/c-fos+)/EYFP+ cells in dCA3 when compared with prophylactic saline administration. (M) Prophylactic ketamine did not alter the number of EYFP+ cells in vCA3 when compared with prophylactic saline administration. However, prophylactic ketamine increased the number of (N) c-fos+ and (O) the percent of (EYFP+/c-fos+)/EYFP+ cells when compared with prophylactic saline administration in vCA3 (n = 7–10 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. **p < 0.01. EYFP, enhanced yellow fluorescent protein; Sal, saline; K, ketamine; 4-OHT, 4-hydroxytamoxifen; CFC, contextual fear conditioning; DG, dentate gyrus; CA3, Cornu Ammonis region 3.

Brains were next processed for EYFP and c-fos expression (Figure 5E, F, G, H, I, J). In the dDG, the number of EYFP+ (Figure 5K) and c-fos+ cells (Figure 5L) did not differ between groups, as well as the percent of co-labeled (EYFP+/c-fos+)/EYFP+ cells (Figure 5M). In the vDG, the number of EYFP+ (Figure 5N) and c-fos+ cells (Figure 5O) did not differ between groups, as well as the percent of co-labeled cells (Figure 5P). In dCA3, the number of EYFP+ (Figure 5Q) and c-fos+ cells (Figure 5R) did not differ between groups, as well as the percent of co-labeled cells (Figure 5S). However, in vCA3, while the number of EYFP+ did not differ between the groups (Figure 5T), the number of c-fos+ cells (Figure 5U) and the percent of co-labeled cells (Figure 5V) increased following prophylactic ketamine administration. In accordance our previous data, the levels of activity during encoding (EYFP+ cells) were higher in the DG than in CA3 (Figure 5K versus 5Q), suggesting a preferential role of the DG in encoding (13, 14). These data are consistent with the aforementioned ΔFosB experiment in which we did not observe an effect of ketamine in the dHPC, but vHPC. Overall, these data indicate that ketamine may be effective at attenuating learned fear by altering vCA3 neural ensembles.

To begin to address if prophylactic ketamine broadly alters memory, 129S6/SvEvTac mice was injected with saline or ketamine and 1 week later administered the OF, NOR, and PS paradigms. Prophylactic ketamine did not alter locomotion (Supplemental Figure S03A) as expected (4), and object recognition memory (Supplemental Figure S03B, C). Interestingly, during PS, both groups of mice exhibited comparable levels of freezing following 1-shock CFC in the aversive context A (Supplemental Figure S04, Supplemental Table S02). However, prophylactic ketamine mice froze significantly less in the similar, but neutral context B and had significantly higher levels of discrimination between the two contexts (Supplemental Figure S04G). Prophylactic ketamine mice distinguished between the two contexts more rapidly than prophylactic saline mice, suggesting that prophylactic ketamine decreases fear generalization and accelerates contextual discrimination. Therefore, prophylactic ketamine’s effects are specific to fear-inducing stimuli by possibly modifying vCA3 neural ensembles representing a fear memory.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have shown that prophylactic ketamine administration, but not stress, increases ΔFosB expression in the PFC. Though, in the HPC, prophylactic ketamine administration only in the SD group increased ΔFosB expression in the vDG and vCA3, but not in the dDG or dCA3. Interestingly, blockade of ΔFosB transcriptional activity in vCA3 inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy against stress-induced depressive-like behavior, while overexpression of ΔFosB mimicked and occluded ketamine’s effects. Finally, the prophylactic effect of ketamine was recapitulated in the ArcCreERT2 x ChR2-EYFP mice. We found that ketamine administration attenuated learned fear and altered memory traces representing the CFC experience specifically in vCA3, but not in the vDG. Together these data indicate that prophylactic ketamine may be protective against stress by altering neural ensembles in the vHPC.

Here, we used immunohistochemistry to analyze ΔFosB expression in the PFC and HPC. We focused on these regions because they have been directly implicated in depression both in humans and in pre-clinical models (21, 22, 23, 24). Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated the importance of ΔFosB in these regions (11, 25). Interestingly, prophylactic ketamine administration, but not SD, increased ΔFosB expression in the PFC. Similar results have been reported following chronic fluoxetine administration (25) or environmental enrichment exposure (7). In contrast, SD was reported to induce ΔFosB selectively in the PL, but not in the IL (8), suggesting distinct roles for the different PFC regions (26, 27, 28). Moreover, a recent study reported that ketamine infusions or optogenetic stimulation in the IL mimicked ketamine’s antidepressant responses (29). It is noteworthy that the experimental model, the type of stimulus and the timeline in those experiments were different from ours. Overall our data suggested that the PFC may not be the main brain region mediating prophylactic ketamine efficacy, as alterations are not specific to the mice that experienced SD.

Remarkably, in the SD mice, prophylactic ketamine increased ΔFosB expression in the vHPC, but not in the dHPC. Our results echo multiple lines of evidence demonstrating a functional separation between the vHPC, which is involved in mood and anxiety, and the dHPC which is involved in cognition (12, 14, 30). However, in contrast to our data, chronic fluoxetine, but not stress, was found to increase FosB expression in the dHPC (25). Thus, it remains to be determined if antidepressant drugs other than ketamine can induce different patterns of ΔFosB expression in the HPC.

Previous studies, including ours, suggest a pivotal role of CA3 in stress and depression (14, 31) with pyramidal CA3 neurons showing significant transcriptome-wide changes in response to stress (32). Most promising, experiments conducted in rodents (33, 34) have suggested that ketamine’s effects are mediated by alterations in CA3. Interestingly, inhibition of ΔFosB transcriptional activity in vCA3 reversed prophylactic ketamine’s effects on fear expression, depressive-like, and anxiety-like behavior. These data suggest that ketamine may be protective by altering ΔFosB expression specifically in vCA3. Similar results were previously obtained by Vialou and colleagues (11) using different approaches, showing that transgenic mice overexpressing ΔcJun in the NAc, or mice injected intra-NAc with a viral vector encoding ΔJunD, show increased susceptibility to SD (11). These mice also failed to respond to chronic fluoxetine administration, which typically reversed depression-like behavior (11).

Conversely, overexpression of ΔFosB in vCA3 mimicked ketamine’s effect on attenuating learned fear. In accord with our CFC results, previous work has shown that overexpression of ΔFosB within the NAc reduces an animal’s sensitivity to chronic stress, promotes stress resilience, and mediates antidepressant-like responses (9, 11). It is curious to note that SD also promotes ΔFosB expression throughout HPC (25). Thus, it remains to be clarified how stimuli which produce opposite behavioral outputs, like antidepressant treatments and SD, induce the same ΔFosB expression profile. In contrast, overexpression of ΔFosB in vCA3 was found to induce a depressive-like and anxiogenic phenotype in the FST and EPM, occluding ketamine’s effect. Eagle and colleagues (18) have shown that mice overexpressing ΔFosB showed impaired response in the temporally dissociated passive avoidance (TDPA), an emotion-based task and increased anxiety in the EPM. Further investigation will be needed to explain how ΔFosB overexpression can produce opposite behavioral outcomes in different tasks.

Notably, depressed patients often exhibit both mood and memory alterations, suggesting a correlation between the two phenomena. Thus, here, we also wanted to assess the potencies of ketamine’s protective effects on memory representing a stressful experience. Here, the prophylactic ketamine effect on fear expression was recapitulated in the ArcCreERT2 mice. Ketamine has already been found to influence memory and plasticity mechanisms within the hippocampus (35, 36) and the effects demonstrated in our study are similar to previous studies involving NMDA receptor antagonists on fear expression (37, 38, 39). However, no previous group has administered prophylactic ketamine to assess fear memory trace expression. In contrast to our result, a recent study showed that fear memories reactivated under ketamine were subsequently stronger (40). It is noteworthy, however, that the time window and dosage of administration, the behavioral paradigms, and the animal model used in this study were different.

Most promising, the memory traces corresponding to the stressful experience were localized in the HPC as previously reported (14, 16), but ketamine was found to increase the number of c-fos+ cells and the percentage of co-labeled/eYFP cells, without affecting the number of EYFP+ cells in vCA3. The evidence that ketamine did not affect the number of EYFP+ cells is consistent with our CFC training data as we found that prophylactic ketamine does not affect memory encoding. Moreover, the increase in the number of c-fos+ cells following prophylactic ketamine administration is in accord with a recent study showing that ketamine induced marked c-fos expression in different brain regions (41). In contrast, however, high c-fos expression was previously associated with an increased freezing response (42, 43, 44) instead of a reduced response. It is likely that the increased neuronal activation that we observed following ketamine administration might be protective by activating a signaling pathway to reducing fear expression (45, 46). Alternatively, the increased c-fos expression could reflect hyperactivity of vCA3, which would likely impair memory retrieval, as overexpression of an IEG could lead to generalized hyperactivity and memory deficits (47).

Prophylactic ketamine did not affect general locomotor activity or object recognition memory, suggesting that ketamine does not affect other type of learning (3). Interestingly, prophylactic ketamine was found to decrease fear generalization, excluding the possibility that the attenuation in fear response which was observed following prophylactic ketamine represented a memory impairment. A future experiment to silence the vCA3 cells activated during the CFC context exposure is necessary; here, we would expect to abolish prophylactic ketamine efficacy on fear expression. Future studies are needed to better understand the circuitry underlying prophylactic ketamine efficacy on stress-induced fear behavior.

In summary, these experiments demonstrated that prophylactic ketamine may induce protective effects by altering neural ensembles specifically in vCA3. How long this prophylaxis persists is as of yet unknown. Whether subsequent injections would have a similar, increasing, or deleterious effect on stress resilience also has yet to be tested. However, we did interestingly determine for the first time a ketamine-induced neural signature specifically in vCA3, paving the way to novel therapeutic approaches aimed at protecting and preventing at-risk patients from developing not only stress-induced disorders but also stress-induced cognitive disorders.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Transcriptionally silencing or overexpressing ΔFosB activity does not affect locomotor activity but does prevent the ketamine-induced decrease in anxiety-like behavior. (A) In the ΔJunD cohort, all groups of mice had comparable levels of basic movements in the OF. (B) In the ΔJunD cohort, there was no effect of Virus or Drug, but there was a significant Virus x Drug interaction on time in the closed arms in the EPM. Prophylactic ketamine GFP mice exhibited decreased time in the closed arms when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. Silencing ΔFosB expression inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy on anxiety-like behavior. (C) In the ΔFosB cohort, all groups of mice had comparable levels of basic movements in the OF. (D) In the ΔFosB cohort, there was an overall effect of Virus and of Drug, and a significant Virus x Drug interaction on time in the closed arms in the EPM. Prophylactic ketamine GFP mice exhibited decreased time in the closed arms when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. Overexpression of FosB expression inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy on anxiety-like behavior. (n= 7–9 male mice per group). Error bars represent ± SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.0001. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; OF, open field; EPM, elevated plus maze; GFP, green fluorescent protein; sec, seconds; min, minutes.

Figure S2. ΔFosB expression in vCA3 following viral manipulation. Bar graph showing ΔFosB expression in vCA3. Ketamine increases ΔFosB expression in GFP-injected mice. Ketamine does not alter ΔFosB expression in ΔJunD-injected mice. Mice injected with ΔFosB virus have increased ΔFosB expression in vCA3. Ketamine further increases ΔFosB expression in ΔFosB-injected mice. (n = 3–4 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Figure S3. Prophylactic ketamine does not influence locomotor activity or novel object recognition memory. (A) Prophylactic saline and ketamine mice had similar levels of locomotor activity. (B) Schematic of NOR paradigm. (C) Prophylactic saline and ketamine mice had increased preference for a novel object when compared to the constant object, but did not differ from each other. (n = 10 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; OF, open field; NOR, novel object recognition; sec, seconds; min, minutes.

Figure S4. Prophylactic ketamine accelerates contextual discrimination and decreases fear generalization. (A) Experimental paradigm. Both groups of mice had comparable freezing levels during CFC encoding (B) and after receiving the shock (C). (D, E, F) Prophylactic saline and ketamine mice freeze equally in the aversive A context throughout the PS task. However, prophylactic ketamine mice freeze significantly less in the similar, but neutral context B when compared with prophylactic saline mice. (G) On days 6 and 8, prophylactic ketamine mice had a significantly higher discrimination ratio between the two contexts than saline mice. (H, I) Prophylactic ketamine mice distinguish between the two contexts on Day 6, whereas prophylactic saline mice distinguish between the two contexts starting on Day 7. (J) Prophylactic ketamine mice freeze less on Day 6 than prophylactic saline mice. (n = 10 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; CFC, contextual fear conditioning; PS, pattern separation; sec, seconds.

Table S1. Statistical analysis summary.

Table S2. Contextual information for pattern separation contexts.

Acknowledgments

AM was supported by an NIH DP5 OD017908 and a Rotary Global Grant GG1864162. CTL was supported by an NIH DP5 OD017908. IPP was supported by New York Stem Cell Science (NYSTEM C-029157). RAB was supported by a Coulter Biomedical Accelorator. CAD was supported by an NIH DP5 OD017908, a National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD) Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation (BBRF) (P&S Investigator), New York Stem Cell Science (NYSTEM C-029157), and a gift from For the Love of Travis, Inc. We thank Josephine C. McGowan, Briana K. Chen, and Michael Drew for insightful comments on this project and manuscript.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

AM, RM, IPP, CTL, and AJR report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interests. RAB and CAD are named on provisional and non-provisional patent applications for the prophylactic use of ketamine and related compounds against stress-related psychiatric disorders.

Supplementary material cited in this article will be available online.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Tanielian T, Jaycox LH, Schell TL, Marshall GN, Burnam MA, Eibner C, et al. Invisible Wounds of War: Summary and Recommendations for Addressing Psychological and Cognitive Injuries. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. erratum 62, 709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brachman RA, McGowan JC, Perusini JN, Lim SC, Pham TH, Faye C, et al. Ketamine as a Prophylactic Against Stress-Induced Depressive-like Behavior. Biol Psychiat. 2016;79:776–786. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGowan JC, LaGamma CT, Lim SC, Tsitsiklis M, Neria Y, Brachman RA, et al. Prophylactic ketamine reduces fear expression but does not facilitate extinction. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;42:1577–1589. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amat J, Dolzani SD, Tilden S, Christianson JP, Kubala KH, Bartholomay K, et al. Previous ketamine produces an enduring blockage of neurochemical and behavioral effects of uncontrollable stress. J Neurosci. 2016;36:153–161. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3114-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soumier A, Carter RM, Schoenfeld TJ, Cameron HA. New Hippocampal Neurons Mature Rapidly in Response to Ketamine But Are Not Required for Its Acute Antidepressant Effects on Neophagia in Rats. eNeuro. 2016;3:0116–15. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0116-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehmann ML, Herkenham M. Environmental enrichment confers stress resiliency to social defeat through an infralimbic cortex dependent neuroanatomical pathway. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6159–6173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0577-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vialou V, Bagot RC, Cahill ME, Ferguson D, Robison AJ, Dietz DM, et al. Prefrontal cortical circuit for depression- and anxiety-related behaviors mediated by cholecystokinin: Role of DeltaFosB. J Neurosci. 2014;34:3878–3887. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1787-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donahue RJ, Muschamp JW, Russo SJ, Nestler EJ, Carlezon WA., Jr Effects of striatal deltaFosB overexpression and ketamine on social defeat stress-induced anhedonia in mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:550–558. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nestler EJ, Kelz MB, Chen J. DeltaFosB: a molecular mediator of long-term neural and behavioral plasticity. Brain Res. 1999;835:10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)01191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vialou V, Robison AJ, Laplant QC, Covington HE, 3rd, Dietz DM, Ohnishi YN, et al. ΔFosB in brain reward circuits mediates resilience to stress and antidepressant responses. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:745–752. doi: 10.1038/nn.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kheirbek MA, Drew LJ, Burghardt NS, Costantini DO, Tannenholz L, Ahmari SE, et al. Differential control of learning and anxiety along the dorsoventral axis of the dentate gyrus. Neuron. 2013;77:955–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee I, Kesner RP. Encoding versus retrieval of spatial memory: double dissociation between the dentate gyrus and the perforant path inputs into CA3 in the dorsal hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2004;14:66–76. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denny CA, Kheirbek MA, Alba EL, Tanaka KF, Brachman RA, Laughman KB, et al. Hippocampal memory traces are differentially modulated by experience, time, and adult neurogenesis. Neuron. 2014;83:189–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madisen L, Zwingman TA, Sunkin SM, Oh SW, Zariwala HA, Gu H, et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cazzulino AS, Martinez R, Tomm NK, Denny CA. Improved specificity of hippocampal memory trace labeling. Hippocampus. 2016;26:752–762. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drew MR, Denny CA, Hen R. Arrest of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice impairs single- but not multiple-trial contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 2010;124:446–454. doi: 10.1037/a0020081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eagle AL, Gajewski PA, Yang M, Kechner ME, Al Masraf BS, Kennedy PJ, et al. Experience-dependent induction of hippocampal ΔFosB controls learning. J Neurosci. 2015;35:13773–13783. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2083-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Susaki EA, Ueda HR. Whole-body and Whole-Organ Clearing and Imaging Techniques with Single-Cell Resolution: Toward Organism-Level Systems Biology in Mammals. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:137–157. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikulina EM, Arrillaga-Romany I, Miczek KA, Hammer RP., Jr Long-lasting alteration in mesocorticolimbic structures after repeated social defeat stress in rats: time course of mu-opioid receptor mRNA and FosB/DeltaFosB immunoreactivity. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:2272–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carreno FR, Donegan JJ, Boley AM, Shah A, DeGuzman M, Frazer A, et al. Activation of a ventral hippocampus-medial prefrontal cortex pathway is both necessary and sufficient for an antidepressant response to ketamine. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1298–308. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akil H, Gordon J, Hen R, Javitch J, Mayberg H, McEwen B, et al. Treatment resistant depression: A multi-scale, systems biology approach. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.08.019. pii: S0149–7634:30368–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ressler KJ, Mayberg HS. Targeting abnormal neural circuits in mood and anxiety disorders: from the laboratory to the clinic. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1116–1124. doi: 10.1038/nn1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisch AJ, Petrik D. Depression and hippocampal neurogenesis: a road to remission? Science. 2012;338:72–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1222941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vialou V, Thibault M, Kaska S, Cooper S, Gajewski P, Eagle A, et al. Differential induction of FosB isoforms throughout the brain by fluoxetine and chronic stress. Neuropharmacol. 2015;99:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sierra-Mercado D, Padilla-Coreano N, Quirk GJ. Dissociable roles of prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, ventral hippocampus, and basolateral amygdala in the expression and extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;36:529–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richard JM, Berridge KC. Prefrontal cortex modulates desire and dread generated by nucleus accumbens glutamate disruption. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgos-Robles A, Bravo-Rivera H, Quirk GJ. Prelimbic and infralimbic neurons signal distinct aspects of appetitive instrumental behavior. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuchikami M, Thomas A, Liu R, Wohleb ES, Land BB, DiLeone RJ, et al. Optogenetic stimulation of infralimbic PFC reproduces ketamine’s rapid and sustained antidepressant actions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:8106–8111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414728112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin J, Maren S. Fear renewal preferentially activates ventral hippocampal neurons projecting to both amygdala and prefrontal cortex in rats. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8388. doi: 10.1038/srep08388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergstrom A, Jayatissa MN, Mork A, Wiborg O. Stress sensitivity and resilience in the chronic mild stress rat model of depression; an in situ hybridization study. Brain Res. 2008;1196:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gray JG, Rubin TG, Kogan JF, Marrocco J, Weidmann J, Lindkvist S, et al. Translational profiling of stress-induced neuro- plasticity in the CA3 pyramidal neurons of BDNF Val66Met mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.219. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang C, Shirayama Y, Zhang J, Ren Q, Yao W, Ma M, et al. R-ketamine: a rapid-onset and sustained antidepressant without psychotomimetic side effects. Translational Psychiatry. 2015;5:e632. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang K, Xu T, Yuan Z, Wei Z, Yamaki VN, Huang M, et al. Essential roles of AMPA receptor GluA1 phosphorylation and presynaptic HCN channels in fast-acting antidepressant responses of ketamine. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra123. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aai7884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ardalan M, Wegener G, Polsinelli B, Madsen TM, Nyengaard JR. Neurovascular plasticity of the hippocampus one week after a single dose of ketamine in genetic rat model of depression. Hippocampus. 2016;26:1414–1423. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jett JD, Boley AM, Girotti M, Shah A, Lodge DJ, Morilak DA. Antidepressant-like cognitive and behavioral effects of acute ketamine administration associated with plasticity in the ventral hippocampus to medial prefrontal cortex pathway. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:312–333. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3957-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fanselow MS, Kim JJ. Acquisition of contextual Pavlovian fear conditioning is blocked by application of an NMDA receptor antagonist D,L-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid to the basolateral amygdala. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1994;108:210–212. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falls WA, Miserendino MJ, Davis M. Extinction of fear-potentiated startle: blockade by infusion of an NMDA antagonist into the amygdala. J Neurosci. 1992;12:854–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-03-00854.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gewirtz JC, Davis M. Second-order fear conditioning prevented by blocking NMDA receptors in amygdala. Nature. 1997;388:471–4. doi: 10.1038/41325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Honsberger MJ, Taylor JR, Corlett PR. Memories reactivated under ketamine are subsequently stronger: A potential pre-clinical behavioral model of psychosis. Schizophrenia research. 2015;164:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakao S, Miyamoto E, Masuzawa M, Kambara T, Shingu K. Ketamine-induced c-Fos expression in the mouse posterior cingulate and retrosplenial cortices is mediated not only via NMDA receptors but also via sigma receptors. Brain Res. 2002;926:191–196. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strekalova T, Zörner B, Zacher C, Sadovska G, Herdegen T, Gass P. Memory retrieval after contextual fear conditioning induces c-Fos and JunB expression in CA1 hippocampus. Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:3–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2003.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radulovic J, Kammermeier J, Spiess J. Relationship between Fos Production and Classical Fear Conditioning: Effects of Novelty, Latent Inhibition, and Unconditioned Stimulus. Preexposure. J Neurosci. 1998;18:7452–7461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07452.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knapska E, Maren S. Reciprocal patterns of c-Fos expression in the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala after extinction and renewal of conditioned fear. Learn Mem. 2009;16:486–93. doi: 10.1101/lm.1463909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duman RS, Li N, Liu RJ, Duric V, Aghajanian G. Signaling pathways underlying the rapid antidepressant actions of ketamine. Neuropharmacol. 2012;62:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klugmann M, Wymond Symes C, Leichtlein CB, Klaussner BK, Dunning J, Fong D, Young D, During MJ. AAV-mediated hippocampal expression of short and long homer 1 proteins differentially affect cognition and seizure activity in adult rats. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:347–360. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Transcriptionally silencing or overexpressing ΔFosB activity does not affect locomotor activity but does prevent the ketamine-induced decrease in anxiety-like behavior. (A) In the ΔJunD cohort, all groups of mice had comparable levels of basic movements in the OF. (B) In the ΔJunD cohort, there was no effect of Virus or Drug, but there was a significant Virus x Drug interaction on time in the closed arms in the EPM. Prophylactic ketamine GFP mice exhibited decreased time in the closed arms when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. Silencing ΔFosB expression inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy on anxiety-like behavior. (C) In the ΔFosB cohort, all groups of mice had comparable levels of basic movements in the OF. (D) In the ΔFosB cohort, there was an overall effect of Virus and of Drug, and a significant Virus x Drug interaction on time in the closed arms in the EPM. Prophylactic ketamine GFP mice exhibited decreased time in the closed arms when compared with prophylactic saline GFP mice. Overexpression of FosB expression inhibited prophylactic ketamine efficacy on anxiety-like behavior. (n= 7–9 male mice per group). Error bars represent ± SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.0001. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; OF, open field; EPM, elevated plus maze; GFP, green fluorescent protein; sec, seconds; min, minutes.

Figure S2. ΔFosB expression in vCA3 following viral manipulation. Bar graph showing ΔFosB expression in vCA3. Ketamine increases ΔFosB expression in GFP-injected mice. Ketamine does not alter ΔFosB expression in ΔJunD-injected mice. Mice injected with ΔFosB virus have increased ΔFosB expression in vCA3. Ketamine further increases ΔFosB expression in ΔFosB-injected mice. (n = 3–4 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; GFP, green fluorescent protein.

Figure S3. Prophylactic ketamine does not influence locomotor activity or novel object recognition memory. (A) Prophylactic saline and ketamine mice had similar levels of locomotor activity. (B) Schematic of NOR paradigm. (C) Prophylactic saline and ketamine mice had increased preference for a novel object when compared to the constant object, but did not differ from each other. (n = 10 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; OF, open field; NOR, novel object recognition; sec, seconds; min, minutes.

Figure S4. Prophylactic ketamine accelerates contextual discrimination and decreases fear generalization. (A) Experimental paradigm. Both groups of mice had comparable freezing levels during CFC encoding (B) and after receiving the shock (C). (D, E, F) Prophylactic saline and ketamine mice freeze equally in the aversive A context throughout the PS task. However, prophylactic ketamine mice freeze significantly less in the similar, but neutral context B when compared with prophylactic saline mice. (G) On days 6 and 8, prophylactic ketamine mice had a significantly higher discrimination ratio between the two contexts than saline mice. (H, I) Prophylactic ketamine mice distinguish between the two contexts on Day 6, whereas prophylactic saline mice distinguish between the two contexts starting on Day 7. (J) Prophylactic ketamine mice freeze less on Day 6 than prophylactic saline mice. (n = 10 mice / group). Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. Sal, saline; K, ketamine; CFC, contextual fear conditioning; PS, pattern separation; sec, seconds.

Table S1. Statistical analysis summary.

Table S2. Contextual information for pattern separation contexts.