Abstract

Purpose

To develop an efficient MR technique for ultra-high resolution diffusion MRI (dMRI) in the presence of motion.

Methods

gSlider is an SNR-efficient high-resolution dMRI acquisition technique. However, subject motion is inevitable during a prolonged scan for high spatial resolution, leading to potential image artifacts and blurring. In this study, an integrated technique termed Motion Corrected gSlider (MC-gSlider) is proposed to obtain high-quality, high-resolution dMRI in the presence of large in-plane and through-plane motion. A motion-aware reconstruction with spatially adaptive regularization is developed to optimize the conditioning of the image reconstruction under difficult through-plane motion cases. In addition, an approach for intra-volume motion estimation and correction is proposed to achieve motion correction at high temporal resolution.

Results

Theoretical SNR and resolution analysis validated the efficiency of MC-gSlider with regularization, and aided in selection of reconstruction parameters. Simulations and in-vivo experiments further demonstrated the ability of MC-gSlider to mitigate motion artifacts and recover detailed brain structures for dMRI at 860 m isotropic resolution in the presence of motion with various ranges.

Conclusion

MC-gSlider provides motion-robust, high-resolution dMRI with a temporal motion correction sensitivity of 2s, allowing for the recovery of fine detailed brain structures in the presence of large subject movements.

Keywords: diffusion imaging, high resolution, motion correction, bulk motion, simultaneous multi-slab

Introduction

Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) has been demonstrated to be an important tool to study tissue microstructure (1,2). It has been widely used to assess structural brain connectivity by reconstructing white matter fiber tracts (3), and is also capable of probing neural tissue abnormalities in clinical settings in order to detect and characterize numerous neurological and psychiatric disorders (4). However, a major challenge for dMRI is its low spatial resolution, typically at 1.5-2mm isotropic, which compromises its ability to provide details of the brain’s fine-scale structures, especially at the tissue interfaces such as at gray and white matter boundaries (5,6). The difficulties in achieving high-resolution dMRI originate from i) the inherent low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), ii) the distortion/blurring artifacts of EPI or spiral readout typically used in dMRI, and iii) the sensitivity to motion during long dMRI scans. Recent developments toward mitigating these issues are described below.

In recent years, simultaneous multi-slice (SMS) (7–11) has been used to reduce acquisition time and provide higher SNR efficiency in dMRI, in particular through controlled aliasing approaches (8) such as blipped-CAIPI in EPI (12,13). Nonetheless, multiband (MB) acceleration of 4x or higher is difficult to achieve without significant noise penalty, especially when used in conjunction with in-plane acceleration (Rinplane). This limits the ability of SMS to achieve SNR-efficient short-TR acquisitions for high isotropic resolution whole-brain dMRI at <1mm. In such cases, 3D multi-shot multi-slab imaging (14–18) that can achieve short-TR acquisitions for this resolution/coverage range, is a promising approach to improve SNR efficiency. Recent methods to mitigate slab-boundary artifacts (19,20) and improve robustness of 3D multi-shot multi-slab acquisition in dMRI (16,18) have shown promise. Moreover, simultaneous multi-slab approaches (21–23) have also been developed to enable faster encoding for this SNR efficient acquisition.

To mitigate the distortion/blurring of EPI acquisitions in dMRI (24), a number of in-plane segmented techniques have been developed (25–30). These techniques can achieve excellent mitigation at a cost of longer scan time and increased motion sensitivity. On the other hand, a combined use of in-plane parallel imaging and reduced field-of-view (FOV) acquisition (31–33) has also been developed, which provides good, albeit more limited distortion/blurring mitigation, without the need to resort to multi-shot imaging. Recently, ZOOPPA (32) has enabled whole-brain imaging with reduced distortions through sagittal acquisition with phase-encoding along the head-foot direction (34).

Another major issue in high-resolution dMRI is its motion sensitivity during the long scan time, which causes image degradation and resolution loss. For single-shot EPI (ss-EPI), the diffusion-weighted images can be co-registered to correct for inter-volume motion. However, for multi-shot and multi-slab acquisitions, intra-volume subject movements between different shots or slab-encodings can cause severe artifacts and blurring. Several methods have been proposed to address this problem, including a number of navigator-based motion correction (14,25,35–38) and self-navigated or navigation-free motion correction approaches (35,39–42). Among the navigation-free techniques, augmented multiplexed sensitivity encoding (AMUSE) (42) incorporates motion correction into parallel imaging reconstruction, which reduces the effects of both microscopic and macroscopic motion in high-resolution multi-shot dMRI data. Nonetheless, most methods including AMUSE do not consider the effect of through-plane motion, which would lead to large signal dropout or incorrect mixture of anatomy from different slices.

In our recent work, we proposed the Generalized Slice Dithered Enhanced Resolution-Simultaneous Multislice (gSlider-SMS) technique (22) to achieve high-resolution dMRI, with high SNR and low distortion. This technique combines blipped-CAIPI controlled aliasing with a slab radio frequency (RF) encoding for SNR-efficient, navigator-free, simultaneous multi-slab acquisition. The acquisition also utilizes the ZOOPPA approach for low-distortion ss-EPI, and for the first time achieved in vivo whole-brain dMRI at 600-800 isotropic resolution range. In this study, we extend the gSlider-SMS acquisition/reconstruction framework to create a motion-robust, navigator-free, high-resolution dMRI technique termed motion-corrected gSlider (MC-gSlider), that mitigates both i) the background phase corruption from physiologic and bulk motion, and ii) the actual bulk in-plane and through-plane motion effects. To our knowledge, even though there are some existing methods (14) correcting for in-plane motion for multi-slab diffusion acquisition, no method has been previously proposed to retrospectively correct for the actual 3D bulk motion with or without the use of navigators. In MC-gSlider, a motion-aware reconstruction with spatially varying regularization is developed to optimize the conditioning of the image reconstruction under difficult through-plane motion cases. Additionally, a navigator-free approach for intra-volume motion estimation and correction is proposed to achieve motion correction at a high temporal resolution of 2s. Simulations and in-vivo experiments demonstrated the ability of MC-gSlider to remove motion artifacts and recover detailed brain structure for dMRI at 860 isotropic voxel size in the presence of motion ranging from sub-millimeter to several centimeters.

Theory

gSlider-SMS

In this section, we briefly review the basic theory of gSlider-SMS, based on which we will develop MC-gSlider. The original gSlider-SMS combines simultaneous multi-slab acquisition with a novel RF slab encoding that is similar to Hadamard encoding (43). Several RF slab-encoded volumes are acquired in consecutive TRs and combined to reconstruct a single high-resolution, thin-slice volume. The RF encodings are designed with ‘slice-phase dithering’, such that a different sub-slice within each slab undergoes a π phase modulation for each encoding. This slice phase-dithering not only provides highly independent encoding basis for reconstruction (similar to Hadamard), but also creates high-SNR images in each slab-encoded volume for navigation-free phase correction. During the reconstruction, the simultaneously acquired slabs are first unaliased using leak-block slice-GRAPPA (44). The phase variations due to physiological motion are then estimated and removed using the low frequency phase of each RF encoded data estimated from the center of the k-space. Finally, the corrected slab-volumes can be used to reconstruct the final thin-slice volume using standard linear reconstruction with Tikhonov regularization (22):

| [1] |

Here, is the gSlider RF-encoding matrix containing slab profiles obtained from Bloch simulation, the size of is × ; is a vector of the encoded low-resolution data at a given spatial position along the readout and phase encoding directions (r,p) with a length of ; and is the vector of the corresponding reconstructed high-resolution data with a length of Here, is the gSlider encoding factor, is the number of thick-slabs in each low-resolution volume and is the number of thin-slices in the reconstructed high-resolution data. Note that for each (r,p) position, the reconstruction is performed all in one step across the whole imaging volume along z and not per RF-encoded slab area. This is because the RF slab profiles contain transition bands that extend slightly beyond the desired encoding slab, which creates coupling in the reconstruction across adjacent slabs.

By combining gSlider encoding with SMS, TR can be effectively shortened. Furthermore, by combining gSlider-SMS with zoomed imaging using inferior saturation pulse and in-plane acceleration, the EPI readout time can be shortened, thus reducing in-plane distortions without the need for multi-shot acquisition. This integrated approach provides high resolution data with high SNR efficiency as well as the ability to achieve navigator-free physiological motion correction. However, since several RF slab-encoded volumes are combined to reconstruct each high-resolution diffusion-weighted image, gSlider-SMS can still be sensitive to macroscopic subject motions across these slab-encoded volumes. For typical imaging at 600-800 m with = 5 slab-encoding volumes, each acquired with MB = 2 and TR of 4-5s, the motion sensitivity time frame is 20-25s. Below we outline our MC-gSlider approach to reduce this motion sensitivity time frame to 2-2.5s.

Motion Corrected gSlider (MC-gSlider)

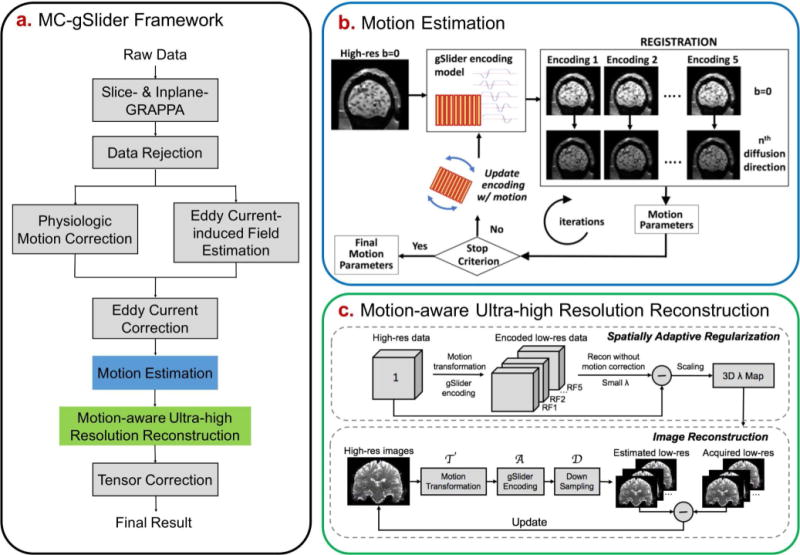

The proposed reconstruction framework includes corrupted data rejection, physiological motion correction, eddy current (EC)-induced distortion correction, bulk motion estimation and motion-aware reconstruction as shown in Figure 1a. Details of the various components are outlined below.

FIG. 1.

(a) The reconstruction framework of the proposed motion-corrected gSlider (MC-gSlider) including data preprocessing steps, (b) iterative motion estimation and (c) motion-aware reconstruction. In the iterative motion estimation process, the updated reference b0 images are obtained by passing a high-resolution b0 volume (created from a b0 gSlider acquisition at the beginning of the scan, assumed motion-free) through a gSlider-encoding simulation that incorporates motion information estimated from the previous iteration.

Corrupted data rejection, physiological motion correction, and eddy-current correction

Prior to bulk motion estimation and correction, several pre-processing steps are needed:

Corrupted data rejection: When large bulk motion occurs during the application of diffusion gradients, significant, unrecoverable signal loss can happen. Such corrupted data are detected by comparing the image intensity of each acquired slab with a threshold, which is determined by the average value of image intensity of that slab across all diffusion directions. Any slab with signal intensity lower than the threshold would be regarded as corrupted data and this slab would be rejected.

Physiological motion correction: is then performed by removing the low frequency phase of each RF encoded data estimated from the center of the k-space.

- Subsequently, EC-induced image distortion is corrected. This distortion is diffusion encoding dependent and consists of in-plane shears, stretches and translations along the phase encoding direction (45,46). The conventional gSlider-SMS corrects for EC-induced distortion on the reconstructed high-resolution images, assuming that there is no difference of head position and EC-induced distortion between different slab-encoded volumes of the same diffusion direction. Both assumptions could be problematic since subject movements can occur between the slab-encoded volumes during the same diffusion direction (in 20-25s), and the different slab-encoded volumes can experience different ECs due to the leftover eddy currents from the previous diffusion encoding gradients, which is especially true when TR is short. To correct for the distortions across different RF-encoded volumes without jeopardizing the encoding information along the slice direction, we estimate the EC-induced field on the acquired RF-encoded volumes images, and correct for the distortions before the motion-aware reconstruction by applying the in-plane transformation in the observed space as follows (47):

where is the coordinate in the observed space and in the desired undistorted space, denotes the voxel displacement field given EC-induced off resonance field , represents EC parameters. This correction only includes in-plane transformation and interpolation, thereby preserves RF-encoding information and provides reliable data to feed into the motion estimation and motion-aware reconstruction process.[2]

Iterative motion estimation

To achieve motion-robust reconstruction, accurate estimation of motions between the RF-encoded volumes is essential. However, the RF-encodings can introduce significant image contrast differences between the RF-encoded volumes, which lead to inaccurate registration. For example, the first RF-encoded volume with phase on the left-most sub-slice will appear to have a bulk volume shift to the right in the slice direction, whereas the last RF-encoding volume with phase on the right-most sub-slice will look like being shifted to the left. To overcome this, motion parameters with 6 degrees of freedom (3 translations and 3 rotations) for each diffusion-weighted RF-encoded volume are estimated relative to a corresponding b = 0 s/mm2 (b0) volume with the same RF-encoding, acquired at the beginning of the scan. Here, it is assumed that there is no motion between the b0 RF-encoded volumes at the start of the scan.

Based on our simulations, sub-voxel subject movements along the slab-encoding direction also create significant contrast differences even among imaging volumes acquired with the same RF-encoding, leading to registration errors. To address this undesirable interaction of motion and RF-encoding, an iterative motion estimation method is developed, as illustrated in Figure 1b. Here, motion estimates are iteratively updated by registering the target RF-encoded diffusion volumes to the updated reference b0 volumes, created using the motion parameters estimated from the previous iteration. Specifically, the reference b0 volumes are re-generated at each iteration by passing a high-resolution b0 volume and the current motion estimates through a forward RF-encoding model. The high-resolution b0 volume is reconstructed by gSlider from the RF-encoded b0 volumes acquired at the start of the scan before motion estimation. As the iteration progresses, the reference b0 volumes should get closer to the motion states of the target diffusion volumes, which should improve the accuracy of the motion estimates.

Motion-aware gSlider reconstruction with spatially-adaptive regularization

Estimated motion parameters are incorporated into a motion-aware reconstruction where artifact-free high-resolution volume of each diffusion direction can be obtained by solving the following minimization problem:

| [3] |

where are the physiological-motion and EC-corrected slab-encoded volumes; denotes the desired high-resolution volume to be reconstructed; is the rigid-motion transformation matrix (48), which transfers the high-resolution volume into motion states based on the sets of estimated motion parameters, where is the same as the gSlider encoding factor for inter-volume motion correction; A is the gSlider encoding matrix which encodes high-resolution volumes with different motion into RF-encoded volumes; represents the sampling matrix selecting encoded volumes with the corresponding motion, and is the regularization parameter.

Note that in-plane motions (both translations and rotations) do not affect the conditioning of Eq. [3], as each RF-encoded volume is fully encoded in-plane. However, through-plane motions can decrease the orthogonality of the slice-dithered RF-encodings and lead to an ill-posed reconstruction. Additionally, rotational and translational motions can cause spatially varying degree of through-plane motion, which leads to spatial variability in the conditioning of the reconstruction. To mitigate the potential of an ill-posed reconstruction, two repetitions of a full RF-encoded gSlider data are acquired consecutively (i.e. ‘double-basis’ = 2 for each diffusion direction to provide more encoding information for motion robustness.

To constrain the reconstruction in ill-posed spatial locations while avoiding over-regularizing the well-posed regions, spatially varying regularization ( ) is employed. In particular, a tailored 3D map is used to reconstruct the motion-corrupted dataset of each diffusion encoding. This map is tailored to the specific motions that occur during that timeframe, and reflects the spatially varying conditioning of the reconstruction. To capture the spatially varying conditioning, a high-resolution image with all voxel values set to one is transformed with the estimated motion parameters and encoded by RF encoding to obtain motion-corrupted low-resolution images. Then, we take the difference map between the high-resolution image, and the corrupted image reconstructed from the low-resolution data via Eq. [3] with a very small amount of regularization (Fig. 1c). Such difference map can be computed quickly and a scaled version of which is used to generate the desired 3D map for each diffusion encoding. Upper and lower thresholds are applied to the resulting maps to constrain the reconstructions to be in a reasonable SNR and point spread function tradeoff range according to the theoretical analysis that will be outlined below in the method section.

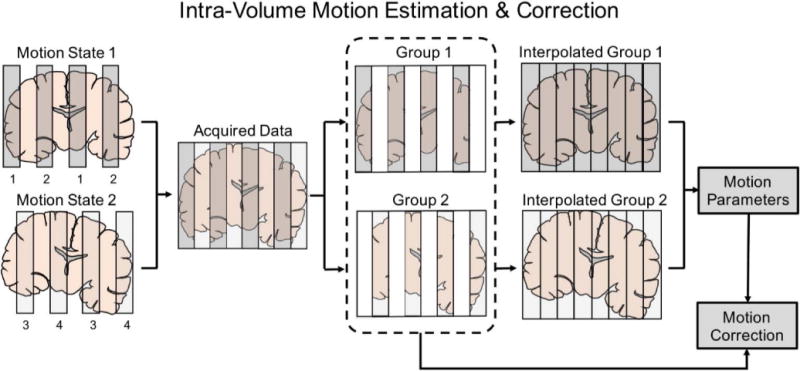

Intra-volume motion estimation and reconstruction

To increase the temporal resolution of our motion estimation and achieve good reconstruction in rapid motion cases, motion parameters will be estimated at two rather than one time-point per RF-encoded volume (TR/2, ~2s). Diffusion images are usually acquired in a slab-interleaved fashion to minimize artifacts due to spin history or cross-talk, therefore whole-brain coverage (with slice gaps) is achieved every TR/2. For motion estimation, the data in each TR/2 slab group are assumed to have the same motion states, and are interpolated to obtain full volumes to allow for motion estimation (Fig. 2). With intra-volume motion correction, the motion transformation matrix in Eq. [3] will now transfer the high-resolution volume into motion states, and the sampling matrix will be altered to select encoded slabs for each group.

FIG. 2.

Intra-volume motion estimation and correction. The volume is divided into two groups with different motion states, which are then interpolated for motion estimation and reconstruction. This allows us to improve the temporal motion correction sensitivity to TR/2. The figure shows the case with 8 total slices acquired with MB=2. Therefore, for each motion state, the 4 slices are acquired in two excitations as indicated by the index underneath the slabs.

Methods

SNR and point spread function analysis

To quantitatively evaluate MC-gSlider, an analysis of the tradeoff between SNR and point spread function (PSF) in the reconstruction was performed. The PSF, which acts as a measure of the effective resolution, was calculated by passing an impulse signal through the forward gSlider-encoding matrix and the reconstruction matrix , as per (22):

| [4] |

where is an impulse vector at the ith position along slice direction, and is the corresponding impulse response. The SNR of the ith voxel was calculated as follows,

| [5] |

where is the variance of the acquired slab data, and j is the index that counts through the different spatial positions along vector and the second dimension of .

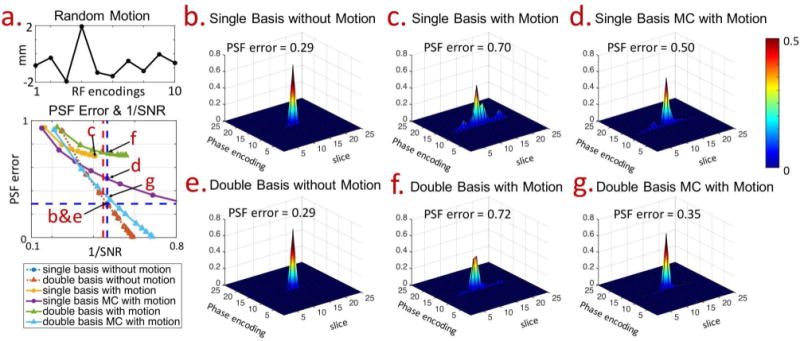

Using Eq. [4] and [5] we performed SNR vs. PSF analysis for MC-gSlider to i) compare the performance of single vs. double basis RF-encoding in the presence of motion, ii) evaluate the effects of different regularizations used in , and iii) characterize the effects of motion estimation errors on the reconstruction. These analyses, which are outlined below, were performed for 5x gSlider encoding ( = 5), but can be easily adapted and applied to other gSlider encoding paradigms.

Single vs. double basis

A comparison of reconstruction performance for single- and double-basis gSlider encoding, with and without motion was conducted. Only through-plane translation was considered since in-plane motions do not affect the conditioning of the reconstruction. PSFs were calculated based on Eq. [4], where the impulse signal was first passed through the single or double basis encoding ( = ), for both motion-present and motion-free cases. Tikhonov regularization was used for the reconstruction:

| [6] |

To examine the benefits of motion correction, motion-corrupted cases were reconstructed using generated from with and without motion information. The PSF error, defined as the normalized root mean squared error (nRMSE) of the input impulse signal and the corresponding impulse response, was calculated for each case. The SNR was also calculated using Eq. [5], where the SNRs of the double-basis cases were normalized by to compensate for the doubled acquisition time to provide a fair comparison. Finally, by sweeping through the regularization parameter ( ) values, a plot of PSF errors vs. 1/SNR (similar to the L-curve) was also generated for each case.

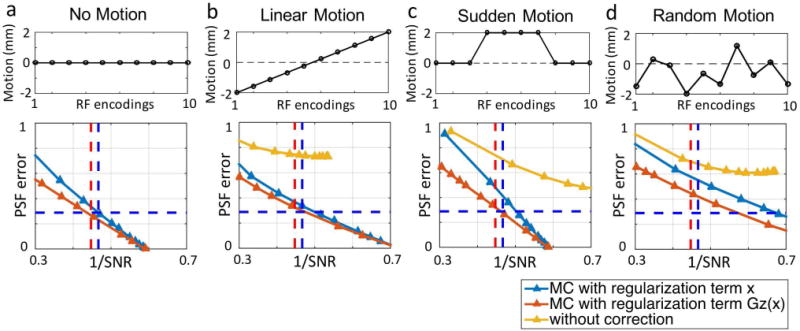

Effects of regularization terms

Two different Tikhonov regularization terms were evaluated: (i) L2 of image value , and (ii) L2 of , where is the gradient operator. The impulse response was calculated via Eq. [4], using the reconstruction matrix in Eq. [6] for (i) and the following Eq. [7] for (ii), respectively.

| [7] |

Here, and are gradient operators along the phase-encoding, readout and slice directions, while , and are the corresponding regularization parameters. First, the PSF error vs. 1/SNR curves of MC-gSlider reconstructions using the two different regularizations ( and ) were evaluated on double-basis data, and compared to the one from the conventional gSlider reconstruction (without motion correction and with L2 regularization on the image). Then, to further optimize the regularization parameters for along the three directions ( and ), different weighting ratios of the regularization parameters were tested. Double-basis data with three different types of motion: linear, sudden and random motion, as well as without motion were used for all the evaluations.

Effects of motion estimation errors

To investigate the effects of motion estimation errors on MC-gSlider, a study was performed on double-basis encoded signal without motion and with random motion, where different amounts of random estimation errors were added to the MC-gSlider reconstruction matrix. regularization with optimal weighting ratio of and (1:1:1), obtained from the above analysis, was used. PSF-errors and SNRs were calculated and compared to the ones obtained through the conventional gSlider without motion correction but with the same regularization.

Experimental validation

To validate the proposed motion-correction framework, phantom and in-vivo motion experiments were performed. Data were acquired on the MGH-USC 3T Connectom scanner with a maximum gradient strength of 300 mT/m and a maximum slew rate of 200 T/m/s (49–51), using a custom-built 64-channel phased-array coil (52).

Phantom Experiments

As a gold standard dataset, diffusion-weighted gSlider data were collected on an anthropomorphic head phantom (phantoms.martinos.org) using the following imaging parameters: FOV = 224 × 136 × 163 mm3; 860 m isotropic resolution, Rinplane × Rzoom = 2 × 1.64; gSlider × MB = 5 × 2; partial Fourier = 6/8; TE/TReffective = 70ms/42s (TR per slab volume = 4.2s); 1 diffusion direction at b = 1000 s/mm2. The acquired data were reconstructed to high-resolution using standard gSlider reconstruction. Rigid motion transformations with 6 degrees of freedom were applied to the high-resolution data to mimic subject movements at a temporal resolution of TR/2. By passing these transformed data through the forward RF encoding model, double-basis RF-encoded data with motion can be simulated. Spatially uncorrelated Gaussian noise was then added to the k-space data (SNR = 10) to mimic in-vivo noise conditions. Finally, the proposed motion estimation and motion-aware reconstruction were applied to this simulated data to obtain high-resolution motion-corrected reconstruction. The conventional gSlider reconstruction was also implemented for comparison.

Three different types of motion profiles (linear, sudden and random motion) across four different ranges of motion (2, 4, 8 and 16 mm°rees) were tested. In each case, rigid motion with 6 degrees of freedom (3 translations and 3 rotations) were added to the data. For MC-gSlider, the spatially-varying regularization was applied with the optimal weighting ratio of 1 between and (obtained via SNR vs. PSF analysis above), while the conventional gSlider reconstruction used Tikhonov regularization on image values as per (22). Three iterations were performed to estimate the motion parameters for MC-gSlider. FLIRT (53,54) was used for motion estimation in each iteration. The nRMSEs of the reconstructed images compared to the reference image were calculated, and the effect of spatially adaptive regularization was investigated by comparing the reconstruction results with and without adaptive .

In-vivo Experiments

Data were acquired from a healthy volunteer with consented institutionally approved protocol. Imaging parameters were: FOV = 220 × 134 × 181 mm3; 860 m isotropic resolution, Rinplane × Rzoom = 2 × 1.64; gSlider × MB = 5 × 2; double-basis encoding; partial Fourier = 6/8; TE/TReffective = 68ms/42s (TR per slab-volume = 4.2s); effective echo-spacing = 0.317ms, 44 diffusion directions at b = 1000 s/mm2 and 3 b0 images, total scan time = 34 minutes. The healthy volunteer was instructed to move his head both in the in-plane and through-plane directions throughout the scan, before which a 34-minute scan was also acquired for reference, where the subject was instructed to keep still. The threshold of each slab for data rejection was set to be 0.8 multiplied by the average intensity across all diffusion directions empirically, and the rejection ratio of the motion data was 0.06% of all the acquired slabs. For MC-gSlider reconstruction, the spatially varying regularization was applied with optimal weighting, while the conventional gSlider reconstruction used Tikhonov regularization on image values. Three iterations were performed to estimate motion parameters in MC-gSlider. Registration in the proposed motion estimation method was performed using the FMRIB Software Library (FSL) FLIRT (53,54). EC-induced field estimation was performed using eddy-current toolbox (47) followed by EC correction using in-house code. EC-induced fields were estimated from a phantom to obtain accurate eddy field estimates that is not corrupted by motion. DTI fitting was then calculated using FSL (55–57). Tensor correction was performed using the average motion parameters of different RF-encoding volumes within one diffusion direction. For standard gSlider reconstruction, no motion-correction was performed between RF-encoded volumes but eddy-current and motion correction across the reconstructed high-resolution diffusion-weighted volumes were performed prior to DTI fitting as per (22).

Results

Figure 3 shows the SNR vs. resolution tradeoff in the reconstruction of single- and double-basis encoding, for the no-motion and the through-slice motion cases (through-slice motion’s time-course shown in Fig. 3a, top). For through-slice motion, results are shown for both the standard and the motion-corrected reconstructions. Figure 3a shows the PSF-error vs. 1/SNR plot (L-curve) for various reconstruction cases, where a normalization has been applied to the SNR of the double-basis cases to account for the doubled scan time. As expected, with no motion, the L-curves for the single- and double-basis are identical. The operating point at the cross of the blue-dotted lines represents reconstruction with an SNR-level of and a PSF side-lobe level of 8%. This operating point was used in (22), as the 8% side-lobe was deemed similar to what is achieved in conventional slice-selective acquisition. The red-dotted vertical line in the figure marks the SNR-level that could be achieved when ideal orthogonal 5x RF-encoding basis is employed. With through-slice motion, reconstructions without correction fare poorly for both single (yellow line) and double (green line) basis, and good slice-resolution (low PSF error) cannot be achieved at any level of SNR tradeoff. The proposed motion-corrected reconstruction mitigates this issue. In particular, for the double-basis case, the reconstruction is much better conditioned and its L-curve is close to that of the no-motion case. Figure 3b shows the PSFs of all the reconstruction cases at a fixed SNR-level of (except for the motion-corrupted single-basis case with no correction, where this SNR level cannot be reached). The PSFs in the p-z plane are shown, where large side-lobes and blurring in the slice-direction are observed in the motion-corrupted cases without correction. These artifacts are largely mitigated through the proposed motion-corrected reconstruction, particularly in the double-basis case.

FIG. 3.

The comparison of reconstruction performances of single- and double-basis gSlider encoding, with and without motion. Figure 3a shows PSF-error vs. 1/SNR curves, with theoretical SNR gain of for 5x gSlider shown as the red vertical dotted-line. The operating point at the cross of the blue dotted-lines represents an SNR level of and PSF side-lobe level of 8%. Note that the SNRs of double-basis data were divided by to compensate for the doubled acquisition time. The PSF profiles for points b, c, d, e, f, g marked by the arrows in Fig. 3a are shown in panels on the right, together with their corresponding PSF-error values.

Figure 4 shows comparison of L-curves obtained from two types of Tikhonov regularized motion-corrected reconstruction ( and ) for double-basis encoding in four motion-scenarios: a) no motion, b) linear, c) sudden, and e) random. The L-curve from the standard reconstruction (without motion-correction and with regularization on ) is also included for each scenario as a reference. In all scenarios, motion correction with regularization resulted in the best SNR vs. resolution tradeoff, with its L-curve being closest to the bottom-left corner of the PSF-error vs. 1/SNR plot. The simulation for regularization was also expanded from the 1D case ( presented in Fig.4 to the 3D case ( and ) in the supporting material (Fig. S1), where the weighting ratio between , and regularization parameters that achieves the best SNR vs. resolution tradeoff across the four motion-scenarios was determined to be 1. This was used in all subsequent results below.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the reconstruction performances of gSlider and MC-gSlider, for data with (a) no motion, (b) linear motion, (c) sudden motion and (d) random motion. For MC-gSlider, reconstructions using two different regularization terms, L2 of image value and L2 of in the slice direction, were analyzed. In all cases, MC-gSlider with L2 regularization on in the slice direction provides the best performance.

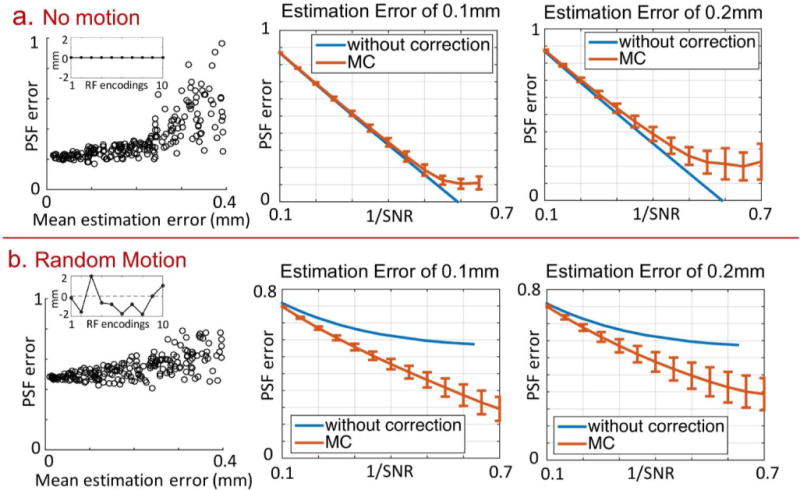

Figure 5 examines the effects of motion-estimation errors on MC-gSlider reconstruction in the i) no motion (top-row) and ii) random motion (bottom-row) scenarios. Double-basis encoding was used along with regularized reconstruction. The left column of Fig. 5 shows the scatter plots of PSF-errors vs. mean estimation errors between adjacent RF-encoding volumes. For each of the two scenarios, 200 motion estimation error cases were simulated with random error profiles, and the regularization parameter in the reconstruction was chosen so that the SNR was hold constant at . As expected, PSF error increases with motion-estimation error in both the no-motion and random-motion scenarios. Based on our simulation, the mean estimation error of 0.2 mm°rees by FSL FLIRT can be reduced to 0.1 mm°rees by our proposed estimation method (Fig. 6a). Therefore, The PSF-error vs. 1/SNR (L-curve) at 0.1 and 0.2 mm mean estimation-error levels were examined as shown in the middle and right columns of Fig. 5. The red-solid lines represent the mean PSF errors, while the corresponding error bars represent the ±one standard deviation width across the relevant simulated motion cases. The blue-solid lines are L-curves for the conventional gSlider without motion correction, and with the same regularization. For the no-motion scenario, at 0.1 mm mean estimation-error level, the L-curve of MC-gSlider is similar to that of the conventional gSlider, with very minor increases in PSF error at the SNR level of interest (1/SNR =1/ = 0.47). As expected, when the estimation error increases to 0.2 mm, the curve deviates more from the conventional gSlider case. For the random-motion scenario, MC-gSlider performs significantly better when compared to the conventional gSlider, with markedly lower PSF errors even in the presence of 0.2 mm mean estimation error.

FIG. 5.

Effects of motion estimation errors on MC-gSlider reconstruction of double-basis data (with regularization term set to the optimal weighting ratio of 1). Two motion scenarios were examined: (a) no motion and (b) random motion. For each scenario, 200 simulated estimation error cases were analyzed, and the resulting scatter plots of PSF errors as a function of mean estimation errors are shown on the left. In each simulated case, the regularization parameter in the reconstruction was chosen so that the SNR was hold constant at . Shown on the right are the PSF errors (mean and standard deviation bars) across different SNR levels of reconstruction, for two mean estimation-error levels of 0.1 and 0.2 mm. The plots for gSlider reconstruction without motion correction are also shown for comparison. Note that the typical operating point would be around 1/SNR = 1/ = 0.47.

FIG. 6.

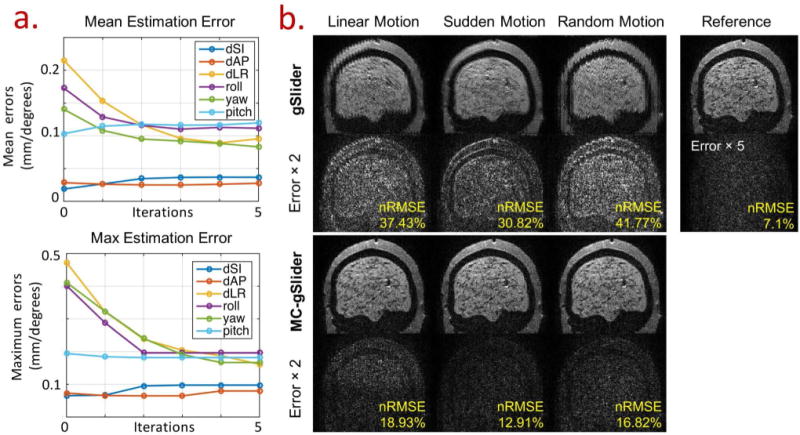

(a) The mean and maximum errors of motion estimation as a function of iterations for random motion case on the head phantom, where random motion of up to ±2 mm°rees across all 6 rigid-motion parameters were applied to the 10 double-basis encoding of 5xgSlider. (b) Comparison of the conventional gSlider and MC-gSlider of data with linear motion, sudden motion, and random motion (±2 mm°rees motion range for all six rigid motion parameters). Three motion estimation iterations were performed to obtain the estimated motion parameters for MC-gSlider reconstruction. The reconstructed images along with their corresponding error maps ( ) and nRMSEs are shown. The error map ( ) below the reference image corresponds to the reconstructed case without any motion, indicating the level of simulated Gaussian noise.

The results of motion simulations using head phantom data and double-basis encoding are shown in Fig. 6–8. Figure 6a shows the performance characterization of the iterative motion estimation obtained from a simulation study, where random motions of up to ± 2mm°rees across all 6 rigid-motion parameters were applied to the 10 double-basis encoding of 5xgSlider (3 translations: Superior-Inferior (dSI), Anterior-Posterior (dAP), Left-Right (dLR), and 3 rotations: S-I axis (roll), A-P axis (yaw) and L-R axis (pitch)). The top and bottom plots show the mean and the maximum estimation errors as a function of iterations, respectively. The estimation errors for in-plane translations (dSI and dAP for this sagittal scan) are low as expected due to the high in-plane resolution in the slab-encoded volume. However, the estimation errors of the other motion parameters are high at the first iteration because of the lower slab-resolution and the undesirable interactions between motion and RF-encoding as outlined in the theory section. After 3 iterations, both the mean and maximum errors of these motion estimates decrease by ~50%, which indicates the effectiveness of the proposed iterative motion estimation.

FIG. 8.

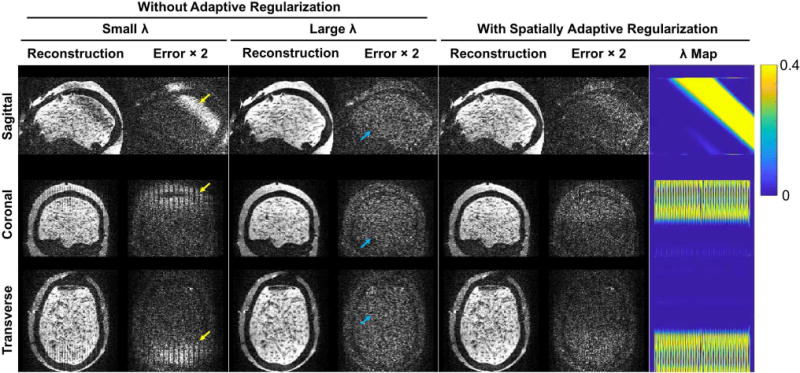

Comparison of reconstructed images for a linear motion case (±2 mm°rees range in all six rigid-motion parameters across 10 double-basis encodings), reconstructed with MC-gSlider using small , large , and spatially adaptive . Three orthogonal planes of the reconstructed images are shown along with the corresponding error maps ( ). The ill-posed regions reconstructed using the small and the well-posed regions with unnecessary blurring using the large are indicated by the yellow and blue arrows respectively. The map for the adaptive regularization case is also shown on the far right.

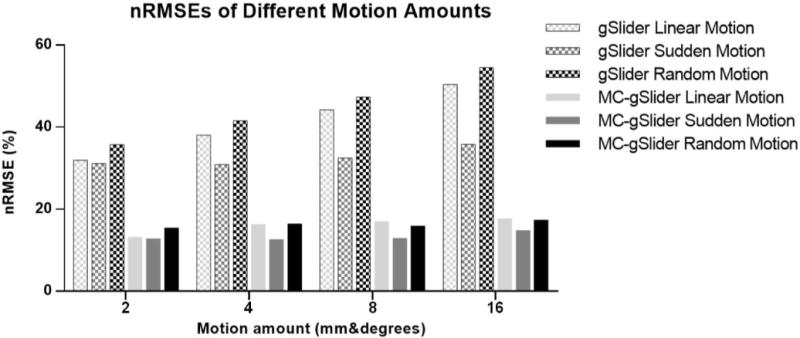

Figure 6b shows reconstruction results from the conventional gSlider (top rows) and MC-gSlider (bottom rows) for three different types of motion profiles previously used in Fig. 4b-d, with a motion range of 4 mm°rees (±2 mm°rees). For MC-gSlider reconstruction, iterative motion-estimation (3 iterations) was used along with spatially-adaptive on . For each reconstruction case, the reconstructed images along with the error maps against a reference high-resolution image are shown. The reference high-resolution image is also shown in the right-most column, along with an error map corresponding to the conventional gSlider reconstruction in the no-motion case. This error map represents the baseline error resulting from the added Gaussian noise in the simulation. In all three motion cases, image reconstructed by the conventional gSlider shows severe artifacts and blurring, resulting in large errors. Most of these artifacts and errors are successfully removed by MC-gSlider. Additional simulation results for a range of simulated motion up to 16 mm°rees can be found in Fig. 7, where MC-gSlider shows consistent improvement over the conventional gSlider. In addition, as the motion range increases, the nRMSEs of MC-gSlider is not increasing as much as the conventional gSlider, indicating the efficacy of MC-gSlider in presence of large motion.

FIG. 7.

nRMSEs of images reconstructed by the conventional gSlider and MC-gSlider for different types and amounts of motions. Head phantom data with different amounts of linear, sudden and random motion were simulated (6 rigid motion were applied simultaneously in each case) and reconstructed using the two methods.

Figure 8 shows a comparison of MC-gSlider performance when reconstruction was performed with and without spatially-adaptive regularization, for a simulated data with ±2 mm°rees linear-motion profile across all six rigid-motion parameters. When a single small value is used (Fig. 8, left), severe jagged-artifacts along the slice-direction (L-R) and signal dropout in the ill-posed regions are present. On the other hand, if a single large is applied to improve the conditioning (Fig. 8, center), unnecessary blurring can occur in the well-posed regions, compromising the effective resolution. Through adaptive (Fig. 8, right), artifacts and signal dropout can be reduced in the ill-posed regions while spatial resolution is maintained in other regions.

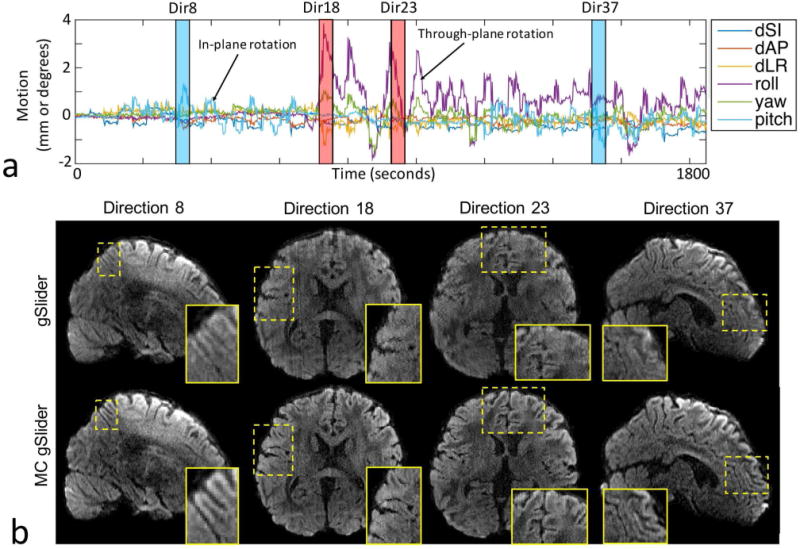

Figure 9 and 10 show in-vivo results from 860 m data acquired with 44 diffusion encodings. Figure 9a shows the estimated motion parameters at a temporal resolution of 2.1s across the 34-minute scan, where large in-plane and through-plane motions can be observed in the blue and red time-blocks, respectively. The top-row of Figure 9b shows reconstruction results from the conventional gSlider at these large motion time-points, where significant blurring is observed. The bottom-row shows reconstruction results from MC-gSlider, where the blurring is satisfactorily mitigated to allow for the recovery of detailed structures around the cortex as shown in the zoomed panels. Figure 10 shows the color-coded fractional anisotropy (cFA) maps from: top-row) reference acquisition with negligible motion, center-row) motion-corrupted acquisition with the conventional gSlider reconstruction, bottom-row) motion-corrupted acquisition with MC-gSlider reconstruction. Three orthogonal views, along with corresponding zoomed-in panels are shown. The cFA maps of the motion-corrupted data, reconstructed using the conventional gSlider show marked deviations from the reference, even after co-registration. These deviations are highlighted in the zoomed-in panels with yellow arrows, where the incorrectly added structures are likely caused by signal mixing from neighboring slices. In comparison, the cFA maps of the motion-corrupted data reconstructed with MC-gSlider is in much better alignment with the reference, indicating the ability of the proposed method to obtain high-isotropic resolution even in presence of large subject movements. Minor differences between the MC-gSlider and the reference still remain, likely from residual displacements between these two separate scans even after co-registration and the residual errors in the correction.

FIG. 9.

(a) Estimated subject movements during a deliberate motion scan. Motion parameters were estimated at a temporal rate of ~2s across the 34-minute scan needed to acquire 860 m data with 44 diffusion encodings, using double-basis RF-encoding. (b) Reconstructed images during large motion periods, using the conventional gSlider and MC-gSlider. Zoomed-ins of the images are shown on the bottom right of each image, which clearly indicating the ability of MC-gSlider to recover detailed brain structures that were lost to motion.

FIG. 10.

Colored-FA results of motion-corrupted data obtained through the conventional gSlider (middle row) and MC-gSlider (bottom row), along with results from the reference data with negligible motion (top row). Spurious structures that are present in the conventional gSlider reconstruction (yellow arrows), likely from unintentional signal mixing between neighboring slices, are removed by MC-gSlider.

Discussion and Conclusion

MC-gSlider is an integrated approach developed to provide efficient acquisition and reconstruction for sub-millimeter isotropic diffusion imaging in presence of subject movements ranging from sub-millimeter to several centimeters. This self-navigated approach was demonstrated in vivo to provide motion estimation and correction at a high temporal rate of ~2s, to recover fine-detailed brain structures. The reconstruction framework has been designed to mitigate various sources of motion-related artifacts: starting with the commonly addressed background phase-corruption from physiologic and bulk motion, to the more demanding correction of the bulk in-plane and through-plane motions themselves. To our knowledge, this is the first technique that has been proposed to retrospectively correct for these 3D bulk motions in multi-slab diffusion acquisitions. In addition to these motions, MC-gSlider also corrects for the subtler differences in EC-induced image distortions across slab-encoding shots.

The comprehensive motion correction in MC-gSlider is possible due to the use of gSlider RF-encoding in the slice direction, which allows unaliased, high-SNR images to be reconstructed directly from each slab-encoded acquisition. In addition to enabling high-temporal, navigation-free motion estimation, this feature also uncouples the motion correction problem from the parallel imaging and k-space reconstruction, making the motion correction much more tractable. With each slab-encoded volume fully-encoded in-plane, all in-plane motion corrections can be performed directly between the slab-encoded volumes without effecting the conditioning of the overall image reconstruction. Further, through-plane motion correction can also be incorporated directly into the gSlider reconstruction, where the use of regularization and double-basis encoding have helped ensure that the reconstruction remain well-posed, even in the presence of large motions. The incorporation of motion correction into gSlider’s linear reconstruction also enables full characterization of SNR vs. resolution tradeoff for the motion-corrected reconstruction, as well as aiding in the development of motion-aware spatially varying regularization which further improves reconstruction performance.

One major challenge in incorporating motion correction into the gSlider reconstruction was obtaining accurate motion parameters. The RF-encodings in gSlider can introduce image contrast differences between different RF-encoded volumes, and sub-voxel movements along the slice direction can lead to contrast differences even between volumes that employ the same RF-encoding, which further complicates motion estimation. The proposed iterative motion estimation addresses these problems by iteratively updating the reference b0 volumes to have the same motion-states and RF-encodings as the target diffusion-weighted volumes. Its effectiveness was demonstrated in phantom simulations, where the mean estimation error was reduced from about 0.2 to 0.1 mm°rees for motion scenario of ±2 mm°rees range (Fig. 6a). Based on our analysis of the effect of motion estimation error on MC-gSlider reconstruction (Fig. 5), such reduction in motion estimation error will significantly reduce reconstruction error and enable better effective resolution.

Another challenge in MC-gSlider is to solve an ill-posed reconstruction caused by compromised/reduced RF-encoding basis set. In particular, through-plane motion changes the RF-encoding along slice direction, making the actual encoding basis less orthogonal. Moreover, the necessary data rejection of corrupted data with large signal loss can also lead to reduced encoding basis. Therefore, double-basis acquisition and regularized reconstruction were employed to improve the conditioning of the reconstruction without sacrificing SNR efficiency. A motion-aware spatially-adaptive regularization on was developed and utilized to constrain the reconstruction in ill-posed spatial locations while avoiding over-regularizing the well-posed regions (Fig. 8). MC-gSlider performed well for various ranges of motion as illustrated in Fig. 7, and the efficacy of reconstruction was not compromised in presence of larger motion range. This is because the 3D encoding A matrix consists of periodic RF encoding bases across different slabs, so for the motion larger than the slab thickness, it is actually the remainder of the motion divided by the slab thickness that is affecting the conditioning of the reconstruction. Because of this reason, the motion range of ±2mm as investigated in the SNR&PSF analysis and phantom simulations is a representative ill-conditioned motion range at the slab thickness of 4.3mm used in the human studies. Future work will explore the incorporation of regularizations that also leverage joint information across diffusion encodings, such as the ones previously employed to denoise and accelerate gSlider acquisitions (through interlaced subsampling of the RF-encoding basis) (58–61). This should further improve MC-gSlider reconstruction and enable motion-robust reconstruction even in the case of single-basis encoding. Data reacquisition (26,62) may also be applied to further mitigate the ill-posed reconstruction problem.

For patient populations that are prone to frequent/rapid motions, such as pediatric patients, intra-volume motions could degrade the image quality of MC-gSlider. Therefore, intra-volume motion correction was developed, where each RF-encoded volume was separated naturally into the two slab-interleaved groups, each with whole imaging volume coverage to achieve motion estimation every TR/2. A faster rate of motion estimation should be feasible through rearranging the slab acquisition order, to create slab groups that span across the whole imaging volume at a faster rate. However, there is a natural tradeoff between temporal resolution and accuracy of such intra-volume motion correction approach. The use of temporal smoothing/denoising across the estimated motion parameters could potentially mitigate this issue. Note that rapid motion could also cause significant spin-history changes to create spatially varying signal modulations that are currently not accounted for in MC-gSlider, which could also lead to reconstruction artifacts. A more sophisticated data rejection scheme to exclude large motion volumes and/or additional regularization/modeling could be explored to mitigate this issue.

MC-gSlider corrects for the inter-diffusion-direction b-matrix rotation by using the averaged parameters across the gSlider encoding volumes in each diffusion direction, while ignoring the intra-direction rotation differences. Such inter-direction strategy has been proven effective for correcting most of the errors from b-matrix rotation (38), since motion typically varies slowly within the acquisition of one diffusion direction, and the amount of rotation is relatively small compared to the change of diffusion gradient for different directions.

In summary, the MC-gSlider provides motion-robust high isotropic resolution dMRI with a temporal motion correction rate of 2s per frame. The method was shown to provide accurate imaging of fine-scale brain structures in the presence of large subject movements. Such technique should improve the robustness of sub-millimeter isotropic dMRI and pave way for its more widespread usage in neuroscientific and clinical settings.

Supplementary Material

FIG. S1. Comparison of different ratios of regularization control parameters and for double-basis data with (a) no motion, (b) linear motion, (c) sudden motion, and (d) random motion. The mesh-grids were created by calculating the SNR and PSF-errors using different values of control parameters in the three directions, each with a range of [0, 2−8, 2−7, …, 20] × C, where C = 0.41. Five lines on the mesh-grids indicating five ratios of the control parameters were evaluated using PSF-error vs. 1/SNR curve as shown on the right column. The third curve (yellow) with ratio of 1 (i.e. with the same control parameter values for all three directions) obtained the best results.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor:

We wish to thank Peter Koopman and Karla Miller for their help with FSL. This work was supported by NIH NIBIB (R01EB020613, R24MH106096, R01EB019437 and R01MH116173) and the instrumentation Grants (S10-RR023401, S10-RR023043, and S10-RR019307).

References

- 1.Basser PJ, Mattiello J, LeBihan D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys J. 1994;66:259–267. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80775-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones DK. The effect of gradient sampling schemes on measures derived from diffusion tensor MRI: a Monte Carlo study. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:807–815. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mori S, Crain BJ, Chacko V, Van Zijl P. Three-dimensional tracking of axonal projections in the brain by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:265–269. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<265::aid-ana21>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moseley M, Kucharczyk J, Mintorovitch J, Cohen Y, Kurhanewicz J, Derugin N, Asgari H, Norman D. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of acute stroke: correlation with T2-weighted and magnetic susceptibility-enhanced MR imaging in cats. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11:423–429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander AL, Hasan KM, Lazar M, Tsuruda JS, Parker DL. Analysis of partial volume effects in diffusion-tensor MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45:770–780. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan Q, Nummenmaa A, Polimeni JR, Witzel T, Huang SY, Wedeen VJ, Rosen BR, Wald LL. HIgh b-value and high Resolution Integrated Diffusion (HIBRID) imaging. NeuroImage. 2017;150:162–176. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larkman DJ, Hajnal JV, Herlihy AH, Coutts GA, Young IR, Ehnholm G. Use of multicoil arrays for separation of signal from multiple slices simultaneously excited. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13:313–317. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200102)13:2<313::aid-jmri1045>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breuer FA, Blaimer M, Heidemann RM, Mueller MF, Griswold MA, Jakob PM. Controlled aliasing in parallel imaging results in higher acceleration (CAIPIRINHA) for multi-slice imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:684–691. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reese TG, Benner T, Wang R, Feinberg DA, Wedeen VJ. Halving imaging time of whole brain diffusion spectrum imaging and diffusion tractography using simultaneous image refocusing in EPI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29:517–522. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moeller S, Yacoub E, Olman CA, Auerbach E, Strupp J, Harel N, Uğurbil K. Multiband multislice GE-EPI at 7 tesla, with 16-fold acceleration using partial parallel imaging with application to high spatial and temporal whole-brain fMRI. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:1144–1153. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feinberg DA, Moeller S, Smith SM, Auerbach E, Ramanna S, Glasser MF, Miller KL, Ugurbil K, Yacoub E. Multiplexed echo planar imaging for sub-second whole brain FMRI and fast diffusion imaging. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Setsompop K, Gagoski BA, Polimeni JR, Witzel T, Wedeen VJ, Wald LL. Blipped-controlled aliasing in parallel imaging for simultaneous multislice echo planar imaging with reduced g-factor penalty. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:1210–1224. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Setsompop K, Cohen-Adad J, Gagoski B, Raij T, Yendiki A, Keil B, Wedeen VJ, Wald LL. Improving diffusion MRI using simultaneous multi-slice echo planar imaging. Neuroimage. 2012;63:569–580. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engström M, Skare S. Diffusion-weighted 3D multislab echo planar imaging for high signal-to-noise ratio efficiency and isotropic image resolution. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:1507–1514. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frost R, Miller KL, Tijssen RH, Porter DA, Jezzard P. 3D Multi-slab diffusion-weighted readout-segmented EPI with real-time cardiac-reordered k-space acquisition. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72:1565–1579. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang H-C, Sundman M, Petit L, Guhaniyogi S, Chu M-L, Petty C, Song AW, Chen N-k. Human brain diffusion tensor imaging at submillimeter isotropic resolution on a 3Tesla clinical MRI scanner. NeuroImage. 2015;118:667–675. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holtrop JL, Sutton BP. High spatial resolution diffusion weighted imaging on clinical 3 T MRI scanners using multislab spiral acquisitions. J Med Imaging. 2016;3:023501–023501. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.3.2.023501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu W, Poser BA, Douaud G, Frost R, In M-H, Speck O, Koopmans PJ, Miller KL. High-resolution diffusion MRI at 7T using a three-dimensional multi-slab acquisition. NeuroImage. 2016;143:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van AT, Aksoy M, Holdsworth SJ, Kopeinigg D, Vos SB, Bammer R. Slab profile encoding (PEN) for minimizing slab boundary artifact in three-dimensional diffusion-weighted multislab acquisition. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73:605–613. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu W, Koopmans PJ, Frost R, Miller KL. Reducing slab boundary artifacts in three-dimensional multislab diffusion MRI using nonlinear inversion for slab profile encoding (NPEN) Magn Reson Med. 2016;76:1183–1195. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost R, Jezzard P, Porter DA, Tijssen R, Miller K. Simultaneous multi-slab acquisition in 3D multislab diffusion-weighted readout-segmented echo-planar imaging. Proceedings of the 21st Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. 2013; p. 3176. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setsompop K, Fan Q, Stockmann J, Bilgic B, Huang S, Cauley SF, Nummenmaa A, Wang F, Rathi Y, Witzel T. High-resolution in vivo diffusion imaging of the human brain with generalized slice dithered enhanced resolution: Simultaneous multislice (gSlider-SMS) Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:141–151. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruce IP, Chang H-C, Petty C, Chen N-K, Song AW. 3D-MB-MUSE: A robust 3D multi-slab, multi-band and multi-shot reconstruction approach for ultrahigh resolution diffusion MRI. NeuroImage. 2017;159:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farzaneh F, Riederer SJ, Pelc NJ. Analysis of T2 limitations and off-resonance effects on spatial resolution and artifacts in echo-planar imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1990;14:123–139. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910140112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butts K, de Crespigny A, Pauly JM, Moseley M. Diffusion-weighted interleaved echo-planar imaging with a pair of orthogonal navigator echoes. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:763–770. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porter DA, Heidemann RM. High resolution diffusion-weighted imaging using readout-segmented echo-planar imaging, parallel imaging and a two-dimensional navigator-based reacquisition. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:468–475. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller KL, Pauly JM. Nonlinear phase correction for navigated diffusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:343–353. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen N-k, Guidon A, Chang H-C, Song AW. A robust multi-shot scan strategy for high-resolution diffusion weighted MRI enabled by multiplexed sensitivity-encoding (MUSE) Neuroimage. 2013;72:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma X, Zhang Z, Dai E, Guo H. Improved multi-shot diffusion imaging using GRAPPA with a compact kernel. NeuroImage. 2016;138:88–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dai E, Ma X, Zhang Z, Yuan C, Guo H. Simultaneous multislice accelerated interleaved EPI DWI using generalized blipped-CAIPI acquisition and 3D K-space reconstruction. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:1593–1605. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Morze C, Kelley DA, Shepherd TM, Banerjee S, Xu D, Hess CP. Reduced field-of-view diffusion-weighted imaging of the brain at 7 T. Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;28:1541–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heidemann RM, Anwander A, Feiweier T, Knösche TR, Turner R. k-space and q-space: combining ultra-high spatial and angular resolution in diffusion imaging using ZOOPPA at 7T. Neuroimage. 2012;60:967–978. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eichner C, Setsompop K, Koopmans PJ, Lützkendorf R, Norris DG, Turner R, Wald LL, Heidemann RM. Slice accelerated diffusion-weighted imaging at ultra-high field strength. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71:1518–1525. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setsompop K, Feinberg DA, Polimeni JR. Rapid brain MRI acquisition techniques at ultra-high fields. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:1198–1221. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bammer R, Aksoy M, Liu C. Augmented generalized SENSE reconstruction to correct for rigid body motion. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57:90–102. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aksoy M, Liu C, Moseley ME, Bammer R. Single-step nonlinear diffusion tensor estimation in the presence of microscopic and macroscopic motion. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:1138–1150. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holdsworth SJ, Skare S, Newbould RD, Bammer R. Robust GRAPPA-accelerated diffusion-weighted readout-segmented (RS)-EPI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:1629–1640. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong Z, Wang F, Ma X, Dai E, Zhang Z, Guo H. Motion-corrected k-space reconstruction for interleaved EPI diffusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pipe JG. Motion correction with PROPELLER MRI: application to head motion and free-breathing cardiac imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:963–969. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199911)42:5<963::aid-mrm17>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu C, Bammer R, Kim Dh, Moseley ME. Self-navigated interleaved spiral (SNAILS): application to high-resolution diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:1388–1396. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu C, Moseley ME, Bammer R. Simultaneous phase correction and SENSE reconstruction for navigated multi-shot DWI with non-cartesian k-space sampling. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:1412–1422. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guhaniyogi S, Chu ML, Chang HC, Song AW, Chen Nk. Motion immune diffusion imaging using augmented MUSE for high-resolution multi-shot EPI. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:639–652. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saritas EU, Lee D, Cukur T, Shankaranarayanan A, Nishimura DG. Hadamard slice encoding for reduced-FOV diffusion-weighted imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72:1277–1290. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cauley SF, Polimeni JR, Bhat H, Wald LL, Setsompop K. Interslice leakage artifact reduction technique for simultaneous multislice acquisitions. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72:93–102. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haselgrove JC, Moore JR. Correction for distortion of echo-planar images used to calculate the apparent diffusion coefficient. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:960–964. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bastin ME. Correction of eddy current-induced artefacts in diffusion tensor imaging using iterative cross-correlation. Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;17:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(99)00026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andersson JL, Sotiropoulos SN. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage. 2016;125:1063–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cordero-Grande L, Teixeira RPA, Hughes EJ, Hutter J, Price AN, Hajnal JV. Sensitivity encoding for aligned multishot magnetic resonance reconstruction. IEEE Trans Comput Imaging. 2016;2:266–280. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Setsompop K, Kimmlingen R, Eberlein E, Witzel T, Cohen-Adad J, McNab JA, Keil B, Tisdall MD, Hoecht P, Dietz P. Pushing the limits of in vivo diffusion MRI for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage. 2013;80:220–233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McNab JA, Edlow BL, Witzel T, Huang SY, Bhat H, Heberlein K, Feiweier T, Liu K, Keil B, Cohen-Adad J. The Human Connectome Project and beyond: initial applications of 300mT/m gradients. Neuroimage. 2013;80:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fan Q, Witzel T, Nummenmaa A, Van Dijk KR, Van Horn JD, Drews MK, Somerville LH, Sheridan MA, Santillana RM, Snyder J. MGH–USC Human Connectome Project datasets with ultra-high b-value diffusion MRI. Neuroimage. 2016;124:1108–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.08.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keil B, Blau JN, Biber S, Hoecht P, Tountcheva V, Setsompop K, Triantafyllou C, Wald LL. A 64-channel 3T array coil for accelerated brain MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:248–258. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5:143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23:S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woolrich MW, Jbabdi S, Patenaude B, Chappell M, Makni S, Behrens T, Beckmann C, Jenkinson M, Smith SM. Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage. 2009;45:S173–S186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage. 2012;62:782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ning L, Setsompop K, Rathi Y. A combined compressed sensing super-resolution diffusion and gSlider-SMS acquisition/reconstruction for rapid sub-millimeter whole-brain diffusion imaging. Proceedings of the 24th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Singapore. 2016; p. 4212. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ning L, Setsompop K, Michailovich O, Makris N, Shenton ME, Westin C-F, Rathi Y. A joint compressed-sensing and super-resolution approach for very high-resolution diffusion imaging. NeuroImage. 2016;125:386–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haldar JP, Fan Q, Setsompop K. Whole-brain quantitative diffusion MRI at 660 μm resolution in 25 minutes using gSlider-SMS and SNR-enhancing joint reconstruction. Proceedings of the 24th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Singapore. 2016; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haldar JP, Setsompop K. Fast high-resolution diffusion MRI using gSlider-SMS, interlaced subsampling, and SNR-enhancing joint reconstruction. Proceedings of the 25th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Honolulu, Hawaii, USA. 2017; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Frost R, Jezzard P, Douaud G, Clare S, Porter DA, Miller KL. Scan time reduction for readout-segmented EPI using simultaneous multislice acceleration: Diffusion-weighted imaging at 3 and 7 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2015;74:136–149. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIG. S1. Comparison of different ratios of regularization control parameters and for double-basis data with (a) no motion, (b) linear motion, (c) sudden motion, and (d) random motion. The mesh-grids were created by calculating the SNR and PSF-errors using different values of control parameters in the three directions, each with a range of [0, 2−8, 2−7, …, 20] × C, where C = 0.41. Five lines on the mesh-grids indicating five ratios of the control parameters were evaluated using PSF-error vs. 1/SNR curve as shown on the right column. The third curve (yellow) with ratio of 1 (i.e. with the same control parameter values for all three directions) obtained the best results.