Abstract

Background

“Dry mouth” syndrome (chronic hyposalivation) can be caused by a number of pathophysiological conditions such as acute and chronic stress exposure, abnormal body weight (both too high and too low ones), eating disorders (such as anorexia nervosa), metabolic syndrome(s), Sjögren’s and Sicca syndromes, drugs and head/neck radiotherapy application. In turn, the chronic hyposalivation as a suboptimal health condition significantly reduces quality of life, may indicate a systemic dehydration, provokes and contributes to a number of pathologies such as a strongly compromised protection of the oral cavity, chronic infections and inflammatory processes, periodontitis, voice and digestive disorders. Consequently, “dry mouth” syndrome might be extremely useful as an indicator for an in-depth diagnostics of both—co-existing and snowballing health-threating conditions. However, predictive diagnostics, targeted prevention and personalisation of treatments are evidently underdeveloped for individuals at high risk suffering from the “dry mouth” syndrome.

Working hypothesis and methodology

In the current study, we have hypothesised that individuals demonstrating “Flammer syndrome” (FS) phenotype may suffer from the “dry mouth” syndrome more frequently, due to disturbed microcirculation, psychological factors (obsessional personality/perfectionism), and diminished feeling of thirst with consequently insufficient daily liquid intake potentially resulting in the systemic dehydration with individually pronounced level of severity. If confirmed, FS phenotyping linked to the chronic hyposalivation might be predictive for individuals at risk identified by innovative screening programmes. To verify the working hypothesis, healthy individuals (negative control group) versus individuals with evident hyposalivation as well as patients diagnosed with periodontitis (positive control group) observed and treated at the dental clinic were investigated. The degree to which an individual is affected by hyposalivation was determined by the Bother xerostomia Index utilising a questionnaire of 10 issue-specific items and monitoring of a typically matt roof of the mouth in dental practice. An extent to which individuals included in the study are the carriers of the FS phenotype was estimated by the specialised 15-item questionnaire.

Results and conclusions

For both—the target group (hyposalivation) and positive control group (periodontitis)—FS phenotype was demonstrated to be more specific compared to the disease-free (negative control) group. Moreover, self-reports provided by interviewed adolescents of the target group frequently recorded remarkable discomfort related to “dry mouth” syndrome, acute and chronic otorhinolaryngological infections and even delayed wound healing. Further, interviewed adolescents do worry about the symptoms which might be indicative for potential diseases; they are also amazed that too little attention is currently paid to the issue by caregivers. In conclusion, FS questionnaire linked to the “dry mouth” syndrome is strongly recommended for application in primary healthcare. Consequently, targeted preventive measures can be triggered early in life. For example, traditional, complementary and alternative medicine demonstrates positive therapeutic effects in individuals suffering from xerostomia. For in-depth diagnostics, epi/genetic regulations involved into pathophysiologic mechanisms of hyposalivation in FS-affected individuals should be thoroughly investigated at molecular level. Identified biomarker panels might be of great clinical utility for predictive diagnostics and patient stratification that, further, would sufficiently improve personalised care to the patient.

Keywords: Predictive preventive personalised medicine, Hyposalivation, Xerostomia, Sicca syndrome, Periodontitis, Voice disorder, Digestive disorder, Flammer syndrome, Phenotype, Dehydration, Patient stratification, Impaired wound healing

Introduction

Saliva is a life-important body fluid essential for an effective immune defence, antibacterial and antifungal function, buffering, remineralisation and lubrication of the oral cavity, tasting, swallowing and speaking, amongst others [1, 2]. Saliva consists of up to 99% of water molecules and about 1% of both organic and inorganic compounds; salivary molecular patterns analysed by saliva-omics is a valuable source of information for early and predictive diagnostics [3]. Salivary secretion is individually ranging between half of litter and litter of the fluid per day [4]. Hyposalivation—a reduced salivary flow also known as the “dry mouth” syndrome and the most common etiologic factor in xerostomia [5]—can be caused by a number of patho/physiological conditions such as acute and chronic stress exposure, abnormal body weight (both too high and too low ones), eating disorders (such as anorexia nervosa), metabolic syndrome(s), Sjögren’s and Sicca syndromes, drugs and head/neck-radiotherapy application [2, 4, 6–10]. Saliva secretion disorder may be manifested at any age. Hence, a strong correlation between disadvantageous and handicapped psychological health conditions (such as stress and anxiety) and development of abnormal saliva flow and its composition can be observed early in life as it has been demonstrated for bullied children [11]. In turn, the chronic hyposalivation as a suboptimal health condition reduces quality of life, may indicate a systemic dehydration, provokes and contributes to a number of pathologies such as a strongly compromised protection of the oral cavity, chronic infections and inflammatory processes, periodontitis, and voice and digestive disorders [2, 4, 10]. Consequently, chronic hyposalivation might be extremely useful as an indicator for an in-depth diagnostics of both—co-existing and snowballing health-threating conditions. An example: as recently published, “dry eyes” and/or “dry mouth” syndrome is more indicative for diagnostics of depression rather than Sjögren’s syndrome itself [12]. In contrast, the factor of hyposalivation is rather neglected in currently applied screening programmes, though recently published articles clearly demonstrate that some phenotypes are strongly predisposed to a systemic dehydration with consequent snowballing health-threating effects such as an increased risk for compromised detoxification and breast cancer predisposition specifically in young subpopulations [13, 14]. Contextually, “Flammer syndrome” (FS) individuals demonstrate strongly reduced feeling of thirst that, if daily liquid intake is not permanently controlled by mind, might be potentially linked to a systemic dehydration [15]. Further, a strongly pronounced FS phenotype has been demonstrated for pre-menopausal breast cancer patients with particularly aggressive metastatic disease [16].

All the above noted actualities have motivated this study estimating potential relationship between the FS phenotype and evidence-based hyposalivation—the “dry mouth” syndrome.

Working hypothesis

The degree to which an individual is affected by hyposalivation or xerostomia (chronic hyposalivation, defined as the subjective sensation of the oral dryness) is ubiquitously determined by the Bother xerostomia Index utilising a questionnaire of 10 issue-specific items [17].

An extent to which individuals included in the study are the carriers of the FS phenotype is estimated by a questionnaire of 15 items [4, 7].

In the current study, we have hypothesised that individuals demonstrating FS phenotype may suffer from the “dry mouth” syndrome more frequently, due to disturbed microcirculation, psychological factors (obsessional personality/perfectionism), and diminished feeling of thirst with consequently insufficient daily liquid intake potentially resulting in the systemic dehydration with individually pronounced level of severity. To verify the working hypothesis, healthy individuals (negative control group) versus individuals with evident hyposalivation as well as patients with periodontitis (positive control group) observed and treated at the dental clinic were interviewed according to the FS questionnaire. Statistically evaluated results are summarised and discussed below.

Materials and methods

Hyposalivation proof

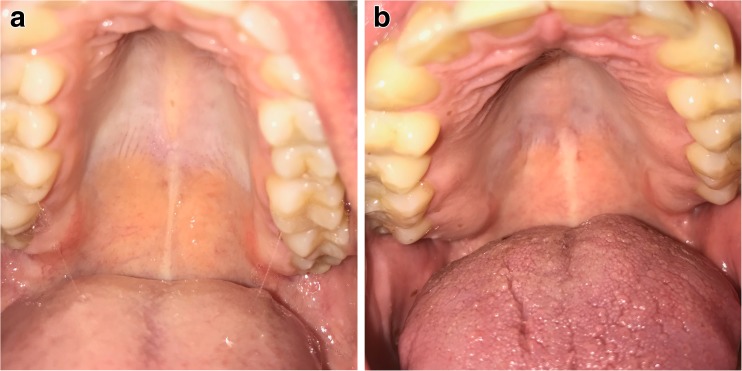

Hyposalivation or xerostomia (chronic hyposalivation) was determined by the Bother xerostomia Index utilising a questionnaire of 10 issue-specific items [17] and monitoring of a typically matt roof of the mouth in dental practice (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Visual estimation of the diagnosed xerostomia in dental practice. a Normally salivated roof of the mouth versus b strongly hyposalivated (matt) roof of the mouth; this methodology has been used additionally to the Bother xerostomia Index utilising a questionnaire of 10 issue-specific items described in the “Materials and methods” section

“Flammer syndrome”: 15-item questionnaire

The “Flammer syndrome” (FS) phenotype became characterised earlier [15]. The FS questionnaire utilised in the actual study has been developed at the University Hospital Basel, Switzerland [18]. The actual version of the FS questionnaire has been effectively applied to study the FS symptomatic in different populations [19] as well as in a spectrum of potentially relevant pathologies such as eye diseases, specific breast cancer subtypes [14, 20] and aggressive metastatic disease [21–23].

Study design

Altogether, 60 individuals recruited at the specialised medical centre (Department of Hospital Dentistry, Voronezh N.N. Burdenko State Medical University, Voronezh, Russia) were involved in this international study and equally distributed between three groups of comparison, namely the disease free group (20 individuals), the target group with hyposalivation (20 individuals) and the group of patients diseased on periodontitis (20 patients). Gender and menopausal status in female individuals were not considered as stratification criteria in the design of the current study; however, corresponding statistical evaluations have been performed (see “Results”).

Disease free individuals

The control group comprised staff members of the medical centre who regularly undergo full check-up of their health condition and who voluntarily participated in the current study. Individuals with no history of major pathologies were included into the (negative) control group of the current study.

Selection of individuals with hyposalivation

The target group comprised staff members and students of the Voronezh N.N. Burdenko State Medical University, who voluntarily participated in the current study. Based on the Fox’s criteria, individuals who positively responded to at least one question numbered 1, 2, 3 or 4 (see Table 1) were classified as persons with hyposalivation [4] and considered for the target group of the study. The scoring according to the Bother xerostomia Index was performed [17]. Finally, individual monitoring of a matt roof of the mouth in the treating dental practice was documented (see Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Ten-item questionnaire to estimate hyposalivation (xerostomia); based on the Fox’s criteria, individuals were classified as suffering from hyposalivation, if they have positively responded at least to one of the italicised questions [4]

| 1. | Do you have a feeling of dry mouth when you eat? |

| 2. | Do you have difficulty swallowing food? |

| 3. | Do you need to drink when eating? |

| 4. | Do you have a feeling of hyposalivation most of the time? |

| 5. | Do you have a feeling of dry mouth at night or when you get up? |

| 6. | Do you have a feeling of dry mouth at other time during the day? |

| 7. | Do you use chewing gum or candy to improve your sense of dry mouth? |

| 8. | Do you wake up at night for drinking water? |

| 9. | Do you have problems of food tasting? |

| 10. | Do you have a feeling of burning tongue from time to time? |

Excluding criteria: Individuals with history of major pathologies such as oncologic diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes mellitus, acute and chronic infectious diseases, rheumatic and autoimmune diseases, as well as pregnant women and persons with alcohol and drug abuse.

Periodontitis patients

Since periodontitis is considered as one of the pathologies resulting from chronic and severe hyposalivation (xerostomia) [4, 9, 10], patients observed and treated due to periodontitis at the Department of Hospital Dentistry, Voronezh N.N. Burdenko State Medical University in Voronezh were recruited to create a positive control group for the current study. No specific excluding criteria were applied to this group.

Statistical analysis

For analytical and statistical evaluations, the data got transferred to Microsoft Excel. SPSS Statistics v20.0.0 software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) was applied. The prevalence of individual symptoms in groups of comparison was evaluated and expressed in percent. Pearson’s chi-square test of associations was applied. p values below 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Statistics for the age, gender and menopausal status in groups of comparison

Table 2 presents statistics provided for the disease free (negative control) group and target group of individuals, who suffer from hyposalivation and patients with periodontitis (positive control group) with 20 participants per each group of comparison. The disease free group created the youngest group, the age mean (33.3 years old) of which was similar to that of the target group (37.2 years old). Substantially, older group was created by patients diagnosed with periodontitis (46.9 years old). Although the difference was found statistically non-significant, the absolute majority of participants were pre-menopausal women in each group of comparison.

Table 2.

Age- and gender-related statistics for the groups of comparison: the age mean of the target group with otherwise healthy individuals, who suffer from the “dry mouth” syndrome is close to this of the negative control group (youngest one); the oldest one is the group of periodontitis patients

| Characteristics | Patient subgroup | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Periodontitis | Hyposalivation | Disease free | ||

| Female | 13 | 12 | 13 | 0.931 |

| Male | 7 | 8 | 7 | |

| Pre-menopausal | 10 | 12 | 10 | 0.193 |

| Post-menopausal | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Patient age mean (min-max) [years] | 46.9 (33–60) | 37.2 (24–54) | 33.3 (19–67) | < 0.001 |

FS prevalence in three groups of comparison

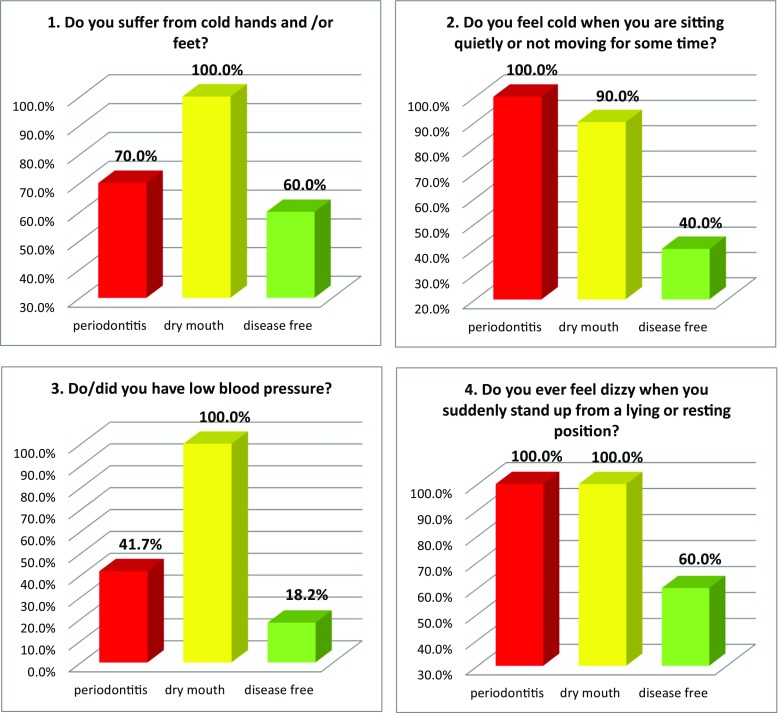

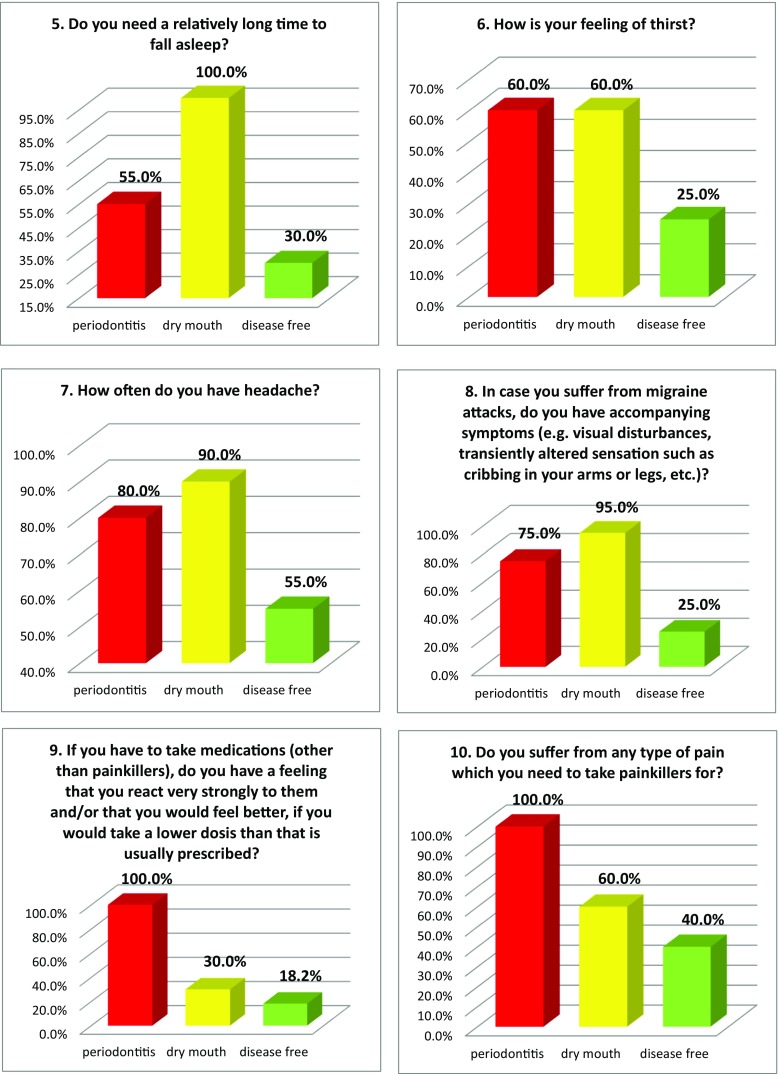

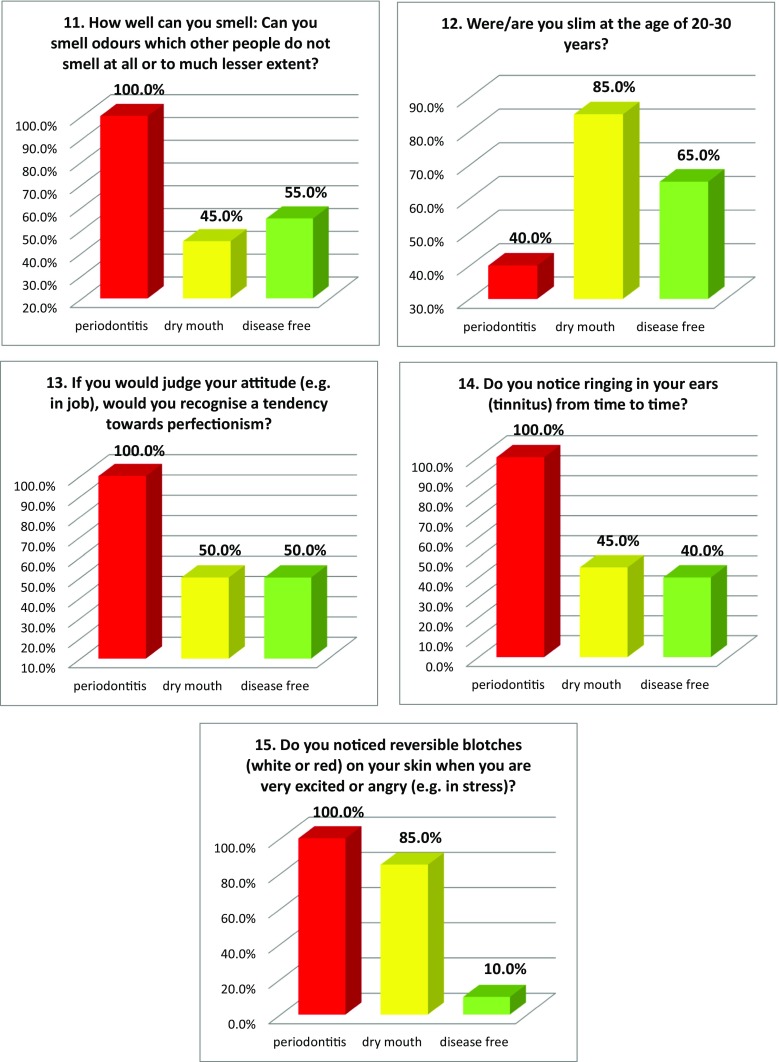

Figure 2 summarises the prevalence of individual “Flammer Syndrome” symptoms utilising the 15-item questionnaire in three groups of comparison. Complementary to that, Table 3 specifies the portion of individual group members, who responded with “no” versus “yes”/“frequently” and/or “sometimes”/“rather” as well as the level of specificity of individual symptoms for groups of comparison providing corresponding level of significance for the group-specific differences. Noteworthy, all 15 items demonstrated highly significant differences between the groups of comparison (see Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of the prevalence of individual symptoms (1–15) of the “Flammer syndrome” phenotype in groups of comparison: “dry mouth” syndrome versus “disease free” reference (negative control) group versus positive control group with periodontitis patients. For more details regarding the patient recruitment and stratification, see “Materials and Methods” section. The prevalence in each individual group is presented in percent of individuals, who have responded to the corresponding question with “frequently” and “sometimes” pooled together. Responders answering “I do not know” were excluded from the overall numbers/calculations; Question 6 answered “I do not feel thirsty and control my liquid intake by mind” is presented; Question 12—answers “very slim” and “slim” are pooled together and presented in percent; Question 13—answers “yes” and “rather” are pooled together and presented in percent

Table 3.

Statistics summarised for the specialised 15-item FS questionnaire; the most representative answer (largest percentage) for each group of comparison is noted. Further, “no” answer is noted for each group as well as “frequently” for the control group, since “no” was the most frequent answer provided in this group. Finally, “Comments” demonstrate which group the corresponding sign/symptom is more versus less typical for, such as H > P > C means more typical for “hyposalivation” than for “periodontitis” and least typical for the control group; H = P means equally typical for “hyposalivation” and “periodontitis”; statistical significance (p) is noted for each item

| Group of comparison | Disease free controls (C) | Hyposalivation (H) | Periodontitis (P) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of item (specialised FS questionnaire) | ||||

| 1 | No—40% Frequently—35% |

Frequently—70% No—0% |

Sometimes—40% No—30% |

H > P > C p = 0.015 |

| 2 | No—60% Frequently—10% |

Sometimes—70% No—10% |

Frequently—65% No—0% |

P > H > C p < 0.001 |

| 3 | No—82% Yes—0% |

Yes—65% No—0% |

Rather—42% No—58% |

H > P > C p < 0.001 |

| 4 | Sometimes—47% No—40% |

Sometimes—100% No—0% |

Frequently—100% No—0% |

P > H > C p < 0.001 |

| 5 | No—70% If feel cold—20% Yes—10% |

Yes—65% If feel cold—35% No—0% |

If feel cold—55% No—45% |

H > P > C p < 0.001 |

| 6 | Normal—55% | Do not feel thirsty/controlled drinking— 60% Normal—0% |

Do not feel thirsty/controlled drinking— 60% Normal—0% |

H = P > C p < 0.001 |

| 7 | No—45% Frequently—15% |

Sometimes—90% No—10% |

Frequently—55% No—20% |

H > P > C p = 0.007 |

| 8 | No—75% Frequently—0% |

Sometimes—95% No—5% |

Frequently—40% No—25% |

H > P > C p < 0.001 |

| 9 | No—82% Frequently—0% |

No—70% Sometimes—30% |

Sometimes—100% No—0% |

P > H > C p < 0.001 |

| 10 | No—60% Frequently—0% |

Sometimes—40% No—40% |

Sometimes—100% No—0% |

P > H > C p < 0.001 |

| 11 | No—45% Frequently—25% |

No—55% Sometimes—45% |

Sometimes—60% No—0% |

P > H > C p = 0.001 |

| 12 | Slim—45% Averaged—35% |

Slim—80% Averaged—15% |

Averaged—60% Slim—40% |

H > C > P p = 0.007 |

| 13 | No—50% Yes—25% |

Rather—50% No—50% |

Rather—70% No—0% |

P > H > C p = 0.001 |

| 14 | No—60% Frequently—0% |

No—55% Sometimes—45% |

Sometimes—75% No—0% |

P > H > C p < 0.001 |

| 15 | No—90% Frequently—0% |

Sometimes—80% No—15% |

Frequently—50% No—0% |

H > P > C p < 0.001 |

For the target group (hyposalivation), FS phenotype was demonstrated to be more specific compared to the disease free (negative control) group with the exception of two items, namely 11 slightly less, and 13 equal to the negative controls. Further, the most significant prevalence of the FS symptoms was demonstrated for altogether 10 items: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12 and 15.

For the periodontitis patients (positive control), similarly to the target group, FS phenotype was demonstrated to be more specific compared to the disease free group with the exception of only one item, namely 12 (average body weight of the majority). Further, the most significant prevalence of the FS symptoms was demonstrated for altogether 12 items: 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14 and 15.

Comparing the target group with periodontitis patients, the FS symptoms of “cold extremities”, “low blood pressure”, “sleep patterns”, “migraine with accompanying symptoms” and “(very) slim body shape” were found to be more specific for the target group, while “altered sensitivity towards drugs”, “pain”, “strong sense of smell”, “meticulous personality”, “tinnitus” and “skin blotches under stress” were found to be more specific for periodontitis patients.

Hyposalivation—interview with selected individuals

Case 1

A 19-year-old female, studying medicine, generally healthy, has been interviewed towards FS symptoms. The interview resulted in 12 positive responses from the maximum of 15 (see the “Materials and methods” section). The negative responses were given regarding the symptoms 5 (answered as “rather normal sleep onset”), 8 (absence of accompanying symptoms of migraine) and 9 (particularly strong reaction towards medication). Particularly noticeable responses were given towards the following symptoms:

Symptom 1—frequently observed cold extremities

Symptom 2—feeling cold frequently

Symptom 3—evidently low blood pressure

Symptom 10—increased pain sensitivity

Symptom 11—strongly pronounced smell perception

Symptom 12—very slim body shape

Symptom 13—strongly pronounced tendency towards perfectionism

Symptom 14—frequent tinnitus

Symptom 15—evident skin blotches in stress situations.

Self-reported additional information:

since early childhood, the patient suffers from acute and chronic otorhinolaryngologic infections: chronic tonsillitis is clinically manifested

records of cold extremities even during warm period of time, remarkably low blood pressure, feeling vertiginous, “dry mouth” syndrome and related discomfort, impaired wound healing

the patient does not feel thirsty and drinks too little

excellent student with remarkably good notes at any educational level

the patients worries about achievements but also about symptoms which might potentially indicate a predisposition to diseases which, however, are not recognised by general practitioners.

Case 2

A 20-year-old male, studying medicine, generally healthy, was interviewed towards FS symptoms. The interview resulted in 11 positive responses from the maximum of 15 (see the “Materials and methods” section). The negative responses were given regarding the symptoms 5 (answered as “rather normal sleep onset”), 8 (absence of accompanying symptoms of migraine), 9 (particularly strong reaction towards medication) and 10 (rather normal pain sensitivity). Particularly noticeable responses have been given towards the following symptoms:

Symptom 1—frequently observed cold extremities

Symptom 2—feeling cold frequently

Symptom 11—strongly pronounced smell perception

Symptom 12—slim body shape

Symptom 13—strongly pronounced tendency towards perfectionism

Symptom 15—evident skin blotches in stress situations.

Self-reported additional information:

since early childhood, the patient suffers from acute and chronic otorhinolaryngologic infections: chronic tonsillitis is clinically manifested

records of cold extremities even during warm period of time, feeling vertiginous, “dry mouth” syndrome and related discomfort, impaired wound healing

the patient does not feel thirsty and drinks too little

excellent student with remarkably good notes at any educational level

the patient worries about achievements but also about above reported symptoms which might potentially indicate a predisposition to diseases which however, are not recognised by general practitioners.

Discussion

In 2018, Springer has selected around 250 articles across all areas with a potential to change the world, which have been awarded the title: “groundbreaking scientific findings that could help humanity and protect our planet” [24]. Specifically, in the category “Medicine and Public Health”, 60 articles have been selected [25], one of which published by the Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology clearly demonstrates the added value of patients’ self-reports [26]. The paper emphasises the crucial role of the patient experience as “a key measure of health-care quality”. Hearing the patient voice at greater volume, indeed, should be the leading principle of personalised healthcare. Contextually, early this year, EPMA J. has published a self-report of an individual with a strongly pronounced “Flammer syndrome” phenotype, who provided a lot of crucial information indicating a predisposition to several pathologies and caregivers’ mistakes who ignored mild signs and symptoms appeared early in life of and self-reported by the patient [27]. Due to potential relevance of the FS phenotype monitored early in life, and a number of pathological conditions recorded later on for the person introduced in the above noted paper, current project has carefully analysed signs and symptoms reported for the adolescent period of life which, if not paid attention to, may potentially lead to severe complications and clinically manifested severe pathologies. Although, if ignored, the dental component is known to play a central role in transition between precondition and several clinically manifested pathologies [3], evidently mild oral and dental symptoms in FS-affected individuals have not yet been taken into consideration as a potential early predictor. In the current paper, a hypothetical link between signs and symptoms generally known for individuals with the FS phenotype and a predisposition to the “dry mouth” syndrome with potentially health-threatening consequences got thoroughly analysed. Collected data clearly demonstrate the relevance of the FS phenotype for both “dry mouth” syndrome and manifested periodontitis. Moreover, while altogether 10 items of the FS symptoms were prevalent in the target group with hyposalivation of otherwise healthy individuals, the patients with manifested periodontitis demonstrated the prevalence of altogether 12 items typical for FS phenotype (see Fig. 2, Table 3).

Most consolidated answers

The most consolidated answers in the groups of comparison are summarised in Table 3. Seventy percent of individuals with hyposalivation frequently suffer from cold extremities and 65% of patients with periodontitis feel cold soon. One hundred percent of patients with periodontitis feel frequently vertiginous and 100% of individuals feel it at least sometimes. One hundred percent of individuals with hyposalivation have/had earlier low blood pressure and 100% of them noted altered sleep patterns. Ninety percent of individuals with hyposalivation suffer from headache and almost all of them receive a migrainous attack with accompanying symptoms. One hundred percent of patients with periodontitis suffer from pain and tinnitus and all of them note altered drug sensitivity and skin blotches under stress conditions; all of them are perfectionists and recognise smell very strongly.

FS signs and symptoms in individuals with delayed and impaired healing process

Amongst all three groups of comparison, specifically in the target group (hyposalivation) and patients with periodontitis, we have identified a significant number of persons who reported delayed or even impaired healing on themselves (see self-reports for “Case 1” and “Case 2” provided above). This question was included additionally to the 15-item FS questionnaire. Due to a relatively low number of the identified persons, currently, we do not provide any statistical evaluation. However, our preliminary observations of individuals with self-reported delayed and impaired healing process indicate their highly pronounced FS phenotype. The most indicative prevalence of the FS symptoms is for altogether 12 items: 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14 and 15. Similarly to individuals with hyposalivation, individuals of this subgroup feel cold soon and vertiginous, they suffer from increased pain sensitivity and frequent headache/migraine with accompanying symptoms. The majority of them do not feel thirsty. All of them note altered drug sensitivity and very strong sense of smell. All of them estimate their attitude as being perfectionistic. Frequently, they suffer from tinnitus and observe skin blotches under stress conditions.

Concluding remarks and expert recommendations

Chronic hyposalivation—“dry mouth” syndrome (xerostomia)—is a major risk factor for strongly compromised life quality and oral disorders such as dental erosion, caries and periodontal diseases, which, if neglected, may contribute to or even provoke a cascade of follow-up pathologies including systemic inflammatory process and cancer. Moreover, the prevalence of xerostomia in the general population is remarkably high, comprising up to 46% of female and up to 26% of male subpopulations [28]. Therefore, it is astonishing how little attention is paid by caregivers to this health condition, particularly in young populations, where targeted prevention is highly cost-effective. Specifically, predictive diagnostics is strongly underdeveloped for individuals with “dry mouth” syndrome. To our best knowledge, the current paper is the very first one aiming at the precise phenotyping of the “dry mouth” syndrome individuals. Knowing the phenotype with specific symptoms and signs is crucial for creating innovative screening programmes, effective patient stratification, predictive diagnosis and targeted prevention. In our study, we hypothesised the relevance of the “Flammer syndrome” phenotype for the prevalent manifestation of the “dry mouth” syndrome based on the data published earlier [23, 27]. Indeed, on the one hand, primary vascular dysregulation, altered stress reactions, perfectionism, altered sense regulation (such as reduced feeling of thirst) and evident similarities to the Sjögren syndrome are characteristics for the “Flammer syndrome” individuals [23]. On the other hand, manifested Sjögren syndrome, chronic stress (e.g. due to obsessional personality), eating disorders (such as perpetual dieting and anorexia nervosa) and insufficient liquid intake—individually and/or synergistically—have been demonstrated to reduce salivary flow and to alter the salivary composition [9, 10, 29]. Contextually, results of our current study clearly confirm the relevance of the FS phenotype for the manifestation of xerostomia and—against the control group—high prevalence of the specific FS symptoms in “dry mouth” syndrome individuals and patients with periodontal disease as analysed above. Noteworthy, the pilot character of the study should be mentioned as a limitation considering a small number of participants included and involvement of only one medical centre which has recruited individuals and patients for the current study.

What are the next steps recommended?

FS questionnaire is strongly recommended for its application by general practitioners (family doctors) to select individuals at high risk; consequently, targeted preventive measures can be triggered early in life (e.g. teenager age). TCAM (traditional, complementary and alternative medicine) such as acupuncture (by releasing vasodilating neuropeptides and improving microcirculation, activating salivary glands, amongst others) [30, 31] and “Qigong” exercise programme - both demonstrate positive therapeutic effects in individuals with hyposalivation and xerostomia [32]. For in-depth diagnostics, certainly a specific epi/genetic regulation involved into pathophysiologic mechanisms of hyposalivation in FS-affected individuals should be investigated at molecular level. Indeed, altered regulation of the hyposalivation-relevant pathways has been demonstrated for some pathologic conditions such as hypertension [33]. To this end, “multi-omics” might be the first choice for constructing advanced diagnostic tools specifically utilising liquid biopsies as became well justified by the most recent literature [3]. Further, an innovative “machine learning” approach should be considered for the multi-parametric analysis, development of the clinically relevant models and accurate patient stratification [34]. Corresponding biomarker panels might get selected for the patient stratification, predictive diagnostics and targeted prevention. Predictive services might be then offered considering several potential diagnoses: disorders of the oral cavity and digestive tract, voice disease, chronic inflammation such as tonsillitis mentioned in the above listed patient cases and cancer predisposition, amongst others. An individual level of the disease severity can be adequately estimated, once specific biomarker panels are ready for their routine application.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the European Association for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine, EPMA, Brussels, Belgium, for professional support in organising current multicentre study.

Authors’ contributions

Olga Golubnitschaja is the project coordinator who has created scientific concepts and hypotheses presented in the manuscript; she has drafted the manuscript. Anatoly Kunin has coordinated the research, performed patient recruitment and data analysis in Russia, analysed the corresponding patient database and selected disease free individuals for the reference group and individuals with hyposalivation involved in the study. Natalia Moiseeva has provided the final data from interviewing the groups of comparison. Jiri Polivka Jr. has performed complete statistical analysis. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study has been supported by the National Sustainability Program I (NPU I) Nr. LO1503, Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Czech Republic, and MH CZ-DRO (Faculty Hospital in Plzen-FNPl, 00669806) and the Charles University Research Fund (Progres Q39).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent declaration

Healthy individuals were informed about the purposes of the study and have signed their consent for publishing the data. Patients interviewed for creating the case reports were informed about the purposes of the study and have signed their consent for publishing the data.

References

- 1.Pedersen AML, Sørensen CE, Proctor GB, Carpenter GH. Salivary functions in mastication, taste and textural perception, swallowing and initial digestion. Oral Dis. 2018; 10.1111/odi.12867. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Berk LB, Shivnani AT, Small W. Pathophysiology and management of radiation-induced xerostomia. J Support Oncol. 2005;3:191–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mileguir D, Golubnitschaja O. Human saliva as a powerful source of information: multi-omics biomarker panels, In: EPMA World Congress: traditional forum in predictive, preventive and personalised medicine for multi-professional consideration and consolidation. EPMA J. 2017;8:1–54. 10.1007/s13167-017-0108-4.

- 4.Carramolino-Cuéllar E, Lauritano D, Silvestre F-J, Carinci F, Lucchese A, Silvestre-Rangil J. Salivary flow and xerostomia in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Oral Pathol Med. 2018;47:526–530. doi: 10.1111/jop.12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nederfors T. Xerostomia and hyposalivation. Adv Dent Res. 2000;14:48–56. doi: 10.1177/08959374000140010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sreebny LM. Saliva in health and disease: an appraisal and update. Int Dent J. 2000;50:140–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2000.tb00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shigeyama C, Ansai T, Awano S, Soh I, Yoshida A, Hamasaki T, Kakinoki Y, Tominaga K, Takahashi T, Takehara T. Salivary levels of cortisol and chromogranin A in patients with dry mouth compared with age-matched controls. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:833–839. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kisely S. No mental health without oral health. Can J Psychiatr Rev Can Psychiatr. 2016;61:277–282. doi: 10.1177/0706743716632523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulthuis MS, Jan Jager DH, Brand HS. Relationship among perceived stress, xerostomia, and salivary flow rate in patients visiting a saliva clinic. Clin Oral Investig. 2018; 10.1007/s00784-018-2393-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Both T, Dalm VASH, van Hagen PM, van Daele PLA. Reviewing primary Sjögren’s syndrome: beyond the dryness - from pathophysiology to diagnosis and treatment. Int J Med Sci. 2017;14:191–200. doi: 10.7150/ijms.17718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaillancourt T, Duku E, Decatanzaro D, Macmillan H, Muir C, Schmidt LA. Variation in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity among bullied and non-bullied children. Aggress Behav. 2008;34:294–305. doi: 10.1002/ab.20240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzales JA, Chou A, Rose-Nussbaumer JR, Bunya VY, Criswell LA, Shiboski CH, Lietman TM. How are ocular signs and symptoms of dry eye associated with depression in women with and without Sjögren syndrome? Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;191:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golubnitschaja O. Feeling cold and other underestimated symptoms in breast cancer: anecdotes or individual profiles for advanced patient stratification? EPMA J. 2017;8:17–22. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0086-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zubor P, Gondova A, Polivka J, Kasajova P, Konieczka K, Danko J, Golubnitschaja O. Breast cancer and Flammer syndrome: any symptoms in common for prediction, prevention and personalised medical approach? EPMA J. 2017;8:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0089-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konieczka K, Ritch R, Traverso CE, Kim DM, Kook MS, Gallino A, Golubnitschaja O, Erb C, Reitsamer HA, Kida T, Kurysheva N, Yao K. Flammer syndrome. EPMA J. 2014;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1878-5085-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bubnov R, Polivka J, Zubor P, Konieczka K, Golubnitschaja O. “Pre-metastatic niches” in breast cancer: are they created by or prior to the tumour onset? “Flammer Syndrome” relevance to address the question. EPMA J. 2017;8:141–157. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0092-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Challacombe SJ, Osailan SM, Proctor GB (2015) Clinical scoring scales for assessment of dry mouth. In: Carpenter G, editor. Dry mouth: a clinical guide on causes, effects and treatments [Internet]. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2015 [cited 2018 Jul 12]. Available from: //www.springer.com/us/book/9783642551536.

- 18.Flammer Syndrome [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 12]. Available from: http://www.flammer-syndrome.ch/index.php?id=32.

- 19.Konieczka K, Choi HJ, Koch S, Schoetzau A, Küenzi D, Kim DM. Frequency of symptoms and signs of primary vascular dysregulation in Swiss and Korean populations. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2014;231:344–347. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1368239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smokovski I, Risteski M, Polivka J, Zubor P, Konieczka K, Costigliola V, Golubnitschaja O. Postmenopausal breast cancer: European challenge and innovative concepts. EPMA J. 2017;8:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0094-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konieczka K, Todorova MG, Chackathayil TN, Henrich PB. Cilioretinal artery occlusion in a young patient with flammer syndrome and increased retinal venous pressure. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2015;232:576–578. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1545774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konieczka K, Flammer J, Sternbuch J, Binggeli T, Fraenkl S. Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy, normal tension glaucoma, and Flammer syndrome: long term follow-up of a patient. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 2017;234:584–587. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-119564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baban B, Golubnitschaja O. The potential relationship between Flammer and Sjögren syndromes: the chime of dysfunction. EPMA J. 2017;8:333–338. doi: 10.1007/s13167-017-0107-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Change the World - One article at a time [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 12]. Available from: https://www.springernature.com/gp/researchers/campaigns/change-the-world?wt_mc=SocialMedia.Twitter.10.CON417.ctw2018_tw_shared_button&utm_medium=socialmedia&utm_source=twitter&utm_content=ctw2018_tw_shared_button&utm_campaign=10_dann_ctw2018_tw_shared_button.

- 25.Change the World - Medicine and Public Health [Internet]. [cited 2018 Jul 12]. Available from: https://www.springernature.com/gp/researchers/campaigns/change-the-world/medicine-public-health.

- 26.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer care - hearing the patient voice at greater volume. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:763–772. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golubnitschaja O, Flammer J. Individualised patient profile: clinical utility of Flammer syndrome phenotype and general lessons for predictive, preventive and personalised medicine. EPMA J. 2018;9:15–20. doi: 10.1007/s13167-018-0127-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orellana MF, Lagravère MO, Boychuk DGJ, Major PW, Flores-Mir C. Prevalence of xerostomia in population-based samples: a systematic review. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66:152–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.da Luz Neto LM, de Vasconcelos FMN, da Silva JE, Pinto TCC, Sougey ÉB, Ximenes RCC. Differences in cortisol concentrations in adolescents with eating disorders: a systematic review. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018; 10.1016/j.jped.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Naik PN, Kiran RA, Yalamanchal S, Kumar VA, Goli S, Vashist N. Acupuncture: an alternative therapy in dentistry and its possible applications. Med Acupunct. 2014;26:308–314. doi: 10.1089/acu.2014.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blom M, Lundeberg T, Dawidson I, Angmar-Månsson B. Effects on local blood flux of acupuncture stimulation used to treat xerostomia in patients suffering from Sjögren’s syndrome. J Oral Rehabil. 1993;20:541–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1993.tb01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayat-Movahed S, Shayesteh Y, Mehrizi H, Rezayi S, Bamdad K, Golestan B, Mohamadi M. Effects of qigong exercises on 3 different parameters of human saliva. Chin J Integr Med. 2008;14:262–266. doi: 10.1007/s11655-008-0262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Zhong L-J, Wang Y, Liu L-M, Cong X, Xiang R-L, Wu LL, Yu GY, Zhang Y. Proteomic analysis reveals an impaired Ca2+/AQP5 pathway in the submandibular gland in hypertension. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14524. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15211-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabryś HS, Buettner F, Sterzing F, Hauswald H, Bangert M. Design and selection of machine learning methods using radiomics and dosiomics for normal tissue complication probability modeling of xerostomia. Front Oncol. 2018;8:35. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]