Abstract

Establishing left–right asymmetry is a fundamental process essential for arrangement of visceral organs during development. In vertebrates, motile cilia-driven fluid flow in the left–right organizer (LRO) is essential for initiating symmetry breaking event. Here, we report that myosin 1d (myo1d) is essential for establishing left–right asymmetry in zebrafish. Using super-resolution microscopy, we show that the zebrafish LRO, Kupffer’s vesicle (KV), fails to form a spherical lumen and establish proper unidirectional flow in the absence of myo1d. This process requires directed vacuolar trafficking in KV epithelial cells. Interestingly, the vacuole transporting function of zebrafish Myo1d can be substituted by myosin1C derived from an ancient eukaryote, Acanthamoeba castellanii, where it regulates the transport of contractile vacuoles. Our findings reveal an evolutionary conserved role for an unconventional myosin in vacuole trafficking, lumen formation, and determining laterality.

The actin-based motor Myosin1d is needed to establish left–right asymmetry in Drosophila. Here the authors show that myosin 1d has a role in lumen formation, vacuole trafficking and left-right asymmetry establishment during zebrafish development.

Introduction

The biological cues that regulate how and when left–right (LR) patterning is established during development has been a fascinating question that remains unresolved. Several animal models have been used to investigate different theories for establishment of LR asymmetry1. This includes intracellular chirality2, voltage gradient flow3, chromatid segregation4, and motile cilia5. Cilia-driven fluid flow has been reported to be essential for left–right asymmetry in Danio rerio (zebrafish)6, Xenopus laevis (African Clawed Frog)7, Mus musculus (mouse)8, and Oryctolagus cuniculus (rabbit)9. However, a role for cilia is not universally conserved across vertebrates. In chick embryos, symmetry breaking is regulated by asymmetric cell migration around Hensen’s node and does not involve cilia-based flow10. In addition, motile cilia are not associated with LR asymmetries that develop in invertebrates11,12, and for asymmetric looping of the gut and gonad in Drosophila13,14. Therefore, probing common cellular events in different model systems may reveal insights into the early mechanisms of breaking symmetry.

De novo lumen formation by cord hollowing, cavitation, and membrane repulsion has been described for tubular organs during development15. Lumen formation by cord hollowing begins with cellular rearrangement of non-polarized cells to establish a polarized rosette structure that dictates an apical membrane surface. Luminal growth begins with trafficking of membrane vesicles targeted to the apical surface where it fuses with plasma membrane. This process also delivers fluid at the apical surface to expand the lumen. In zebrafish, KV lumen formation is a cord hollowing process16 and its threshold size is critical for creating a unidirectional flow and consistent laterality6. How the KV, a near perfect spherical structure forms at the base of the notochord is not fully established. Evidence from studies on ion channels, such as Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (Cftr) and Na+/K-ATPase, as well as tight junction proteins show that they are critical for establishing KV lumen size17–20. However, additional mechanisms that regulate cellular remodeling and specific lumen shape is not known. Here, we reveal an unconventional myosin, myo1d is required for proper KV lumen formation in zebrafish. For this, vacuolar trafficking by Myo1d and expulsion of intracellular fluid from KV epithelial cells into the lumen is essential for attaining definitive spherical shape and threshold lumen size that specifies embryo laterality.

Results

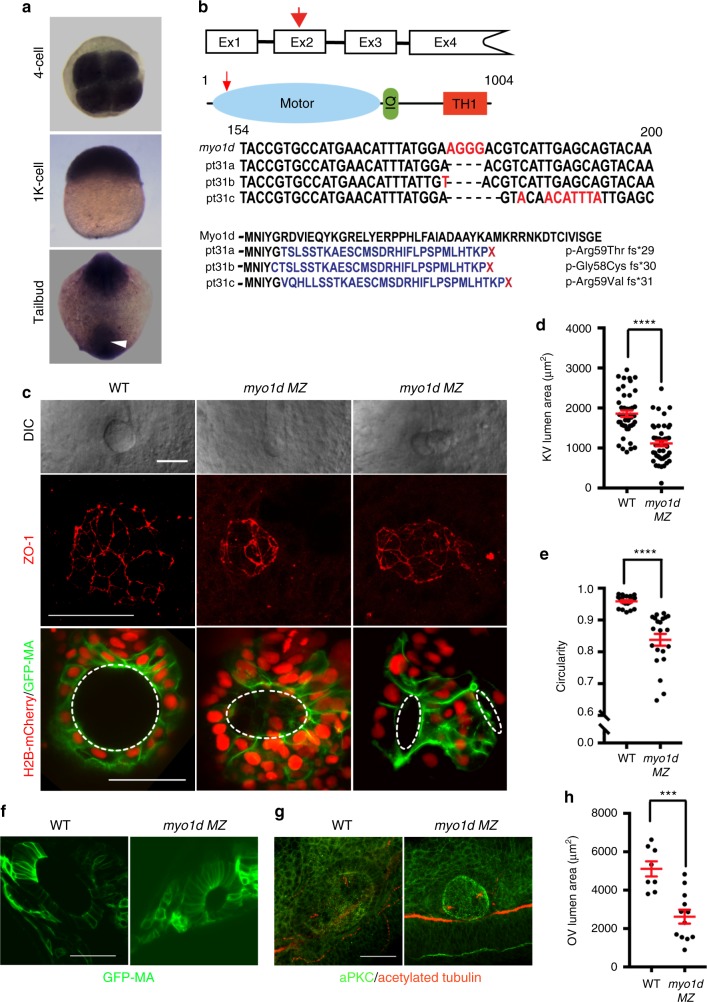

Myo1d is required for proper LRO formation

Prior studies involving Drosophila Myosin1D revealed a role for actin-based molecular motors in establishing LR asymmetry in invertebrates13. We wondered whether myo1d has an evolutionary conserved role in specifying laterality in vertebrates. Zebrafish myo1d is expressed early and ubiquitously, including within the tailbud region where the ciliated KV forms (white arrow, Fig. 1a). We generated myo1d mutations using goldy TALENs21–23 to disrupt the motor domain and reveal its role in LR patterning (Fig. 1b). Three mutant alleles of myo1d, herein named pt31a, b, and c were predicted to cause frame shift and protein truncation (Fig. 1b). However, zygotic homozygous mutants (myo1dpt31a/pt31a) survived to adulthood in a Mendelian ratio suggesting that myo1d maternal expression was sufficient for embryonic development. We generated myo1dpt31a/pt31a maternal-zygotic (MZ) mutants and found that the KV forms into either a small or dysmorphic lumen at the eight somite stage (S), approximately 11 h post fertilization (hpf) (Fig. 1c). Consistently, injection of myo1d translation blocking antisense morpholinos (MO) also decreased KV size (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b & Supplementary Movie 1 & 2). Next, we stained for the tight junction protein, ZO-1 to reveal apical KV morphology. In myo1d MZ mutants, ZO-1 expression revealed small or dysmorphic KV shape compared to controls (Fig. 1c, and Supplementary Fig. 1c). We crossed myo1dpt31a mutants into a transgenic line that labels membranes of KV cells24, Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA)pt21, and confirmed that myo1d MZ mutants have smaller lumen (Fig. 1c, d). Dysmorphic shape of myo1d MZ mutants were further quantified for circularity or isoperimetric quotient, a function of perimeter and area25. We first analyzed KV lumen circularity in embryos during somitogenesis stages to show that as the lumen expands, almost perfect circularity was maintained (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e). In contrast, compared to WT embryos, circularity of KV were decreased in myo1d MZ mutants (Fig. 1c, e). These analyses indicate that myo1d is essential for generating a spherical KV shape and forming a threshold lumen size by 8S. A similar lumen formation defect was also observed in the otic vesicle (OV) (Fig. 1f–h), suggesting that myo1d is essential for the formation of these fluid-filled structures during development. We confirmed that Myo1d expression was detected in KV epithelial cell borders (Supplementary Fig. 2a), whereas Myo1d was absent in mutant KVs (Supplementary Fig. 2b). These data suggest that Myo1d plays a role in the KV epithelial cells and that the pt31a allele is a null mutant.

Fig. 1.

myo1d is required for Kupffer’s vesicle morphogenesis. a myo1d is ubiquitously expression. White arrow demarcates the region where KV is formed. b TALEN mediated genome editing of myo1d. TALENs were designed to target myo1d exon 2 (red arrow) encoding the myosin motor domain (blue). Calmodulin binding IQ motif (green) and Tail Homology 1 (TH1, red) domains are also indicated. Three F1 alleles were isolated, pt31a-c, with predicted amino acid sequence indicated. c–e myo1d MZ mutants showed KV lumen formation defects. Representative DIC images showing KV of myo1d MZ mutants were either smaller and dysmorphic lumens (c). ZO-1 staining at 8S confirmed that the apical surface of KVs were smaller or dysmorphic in myo1d mutants when compared to controls. myo1d MZ;Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) injected with H2BmCherry mRNA showing dysmorphic KV epithelial cell morphology and decreased lumen area, when compared to controls. Lumen marked by dotted circular lines were quantified for area (WT: n = 44, myo1d MZ: n = 46) (d) and circularity (WT: n = 20, myo1d MZ: n = 21) (e). f–h Dysmorphic otic vesicle (OV) observed in myo1d MZ embryos. Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) and myo1d MZ;Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) embryos (f) or stained with aPKC (green) and acetylated tubulin (red) (g) at 24 hpf show smaller OVs and quantified (WT: n = 8, myo1d MZ: n = 12) (h). KV lumen was considered small when it was below threshold lumen size (1000 µm2). Unpaired t test was used with, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 indicated. Data shown in the graphs are mean ± SEM. Scale bar, 50 µm

myo1dMZ mutants display LR patterning defects

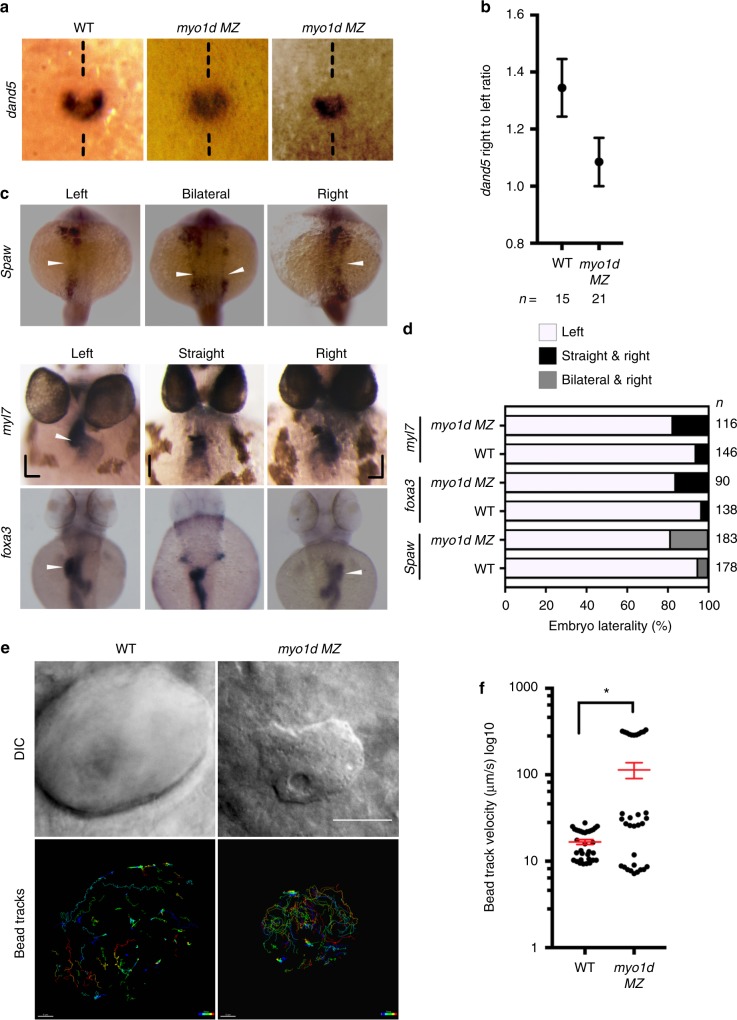

Several reports have shown that a minimum threshold lumen size is necessary for establishing robust KV flow and LR asymmetry in zebrafish18–20,26,27, which prompted us to investigate the mechanism of KV lumen formation. At 6 hpf, the KV is formed from a group of cells called dorsal forerunner cells (DFCs) that form at the base of the organizer6. These cells proliferate and undergo a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition to form a rosette-like structure, where KV lumen forms6. To assess if the abnormal KV lumen phenotype in myo1d MZ mutants are a result of defects in DFC clustering, we analyzed foxj1a expression as a marker for DFCs28. We did not observe differences in foxj1a expression between myo1d MZ and wild-type embryos (Supplementary Fig. 3a). This indicated that DFC clustering and migration was not the cause of defective KV morphogenesis in the myo1d MZ mutants. One of the earliest transcriptional responses to proper KV function is asymmetric expression of the TGFβ antagonist, dand5 (also known as charon)29. In myo1d MZ mutants, the asymmetric dand5 expression on the right- versus left-side KV were reduced when compared to WT embryos at 8S stage indicative of a failure of proper KV function (Fig. 2a, b). We next assessed the expression of spaw, a Nodal gene that marks establishment of definitive left-sided patterning at 18S. In myo1d MZ mutants normal left-sided spaw expression was disrupted such that embryos presented bilateral and even right-sided expression (Fig. 2c, d). We confirmed that the bilateral spaw was not a consequence of midline defects as both T-box transcription factor Ta (tbxta, also known as ntla) and myogenic differentiation 1 (myod1) expression at 10S and 17S were unaffected in myo1d MZ mutants (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Consistently, we detected increased frequency of laterality defects in myo1d MZ mutants (Fig. 2c, d) and in myo1d morphants (Supplementary Fig. 1f). These results suggest that laterality defects we observed in myo1d mutants are not primarily due to midline formation defects, but a result of proper KV formation.

Fig. 2.

myo1d is necessary for KV function and establishing laterality. a, b Relative abundance of dand5 expression on the right vs left were decreased in myo1d MZ mutants compared to WT embryos at 8S. c, d myo1d MZ mutants displayed laterality defects. Heart and gut looping scored by myl7 and foxa3 expression at 72 hpf respectively, spaw expression at 17S (white arrowhead marks expression). Laterality defects were scored in d. e, f myo1d MZ embryos display altered KV flow as analyzed by tracking 0.2 µ FITC fluorescent microbeads injected into KV lumen. DIC images showing KV morphology of control and myo1d MZ mutants (e). Individual beads were mapped showing unidirectional circular movement were lost in myo1d MZ mutants compared to wild-type embryos. Individual bead movement was shown as temporal color-coded tracks. Graph comparing bead track velocity (mean ± SEM) in control (n = 33 tracked beads from three embryos) and myo1d MZ mutant embryos (n = 33 tracked beads from three embryos) (f). Unpaired t test indicate statistical significance * p < 0.05. Scale bar, 50 µm

Since motile cilia in the KV are required for a unidirectional flow and proper laterality30, we determined if loss of myo1d affected ciliogenesis. Acetylated tubulin staining showed that cilia length was normal (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b), but cilia number per KV were less in myo1d MZ mutants (Supplementary Fig. 4c). As KV epithelial cells are monociliated6, we counted KV nuclei bordering the lumen and found fewer cells in myo1d MZ embryos that accounted for the decrease in cilia number (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e). Given that cilia length and number were minimally affected in myo1d MZ mutants, we next determined if disruption in KV fluid flow could explain for the observed laterality defects. To measure fluid flow, we tracked the movement of FITC fluorescent microbeads injected into the KV of WT and myo1d MZ mutants. We noted in myo1d MZ mutants, unidirectional KV fluid flow was lost compared to the control embryos (Fig. 2e, f, and Supplementary Movie 3 & 4). Together, these experiments revealed that in the absence of Myo1d, the process of forming proper KV shape and size is disrupted that results in failure of unidirectional fluid flow and ultimately disrupting LR patterning.

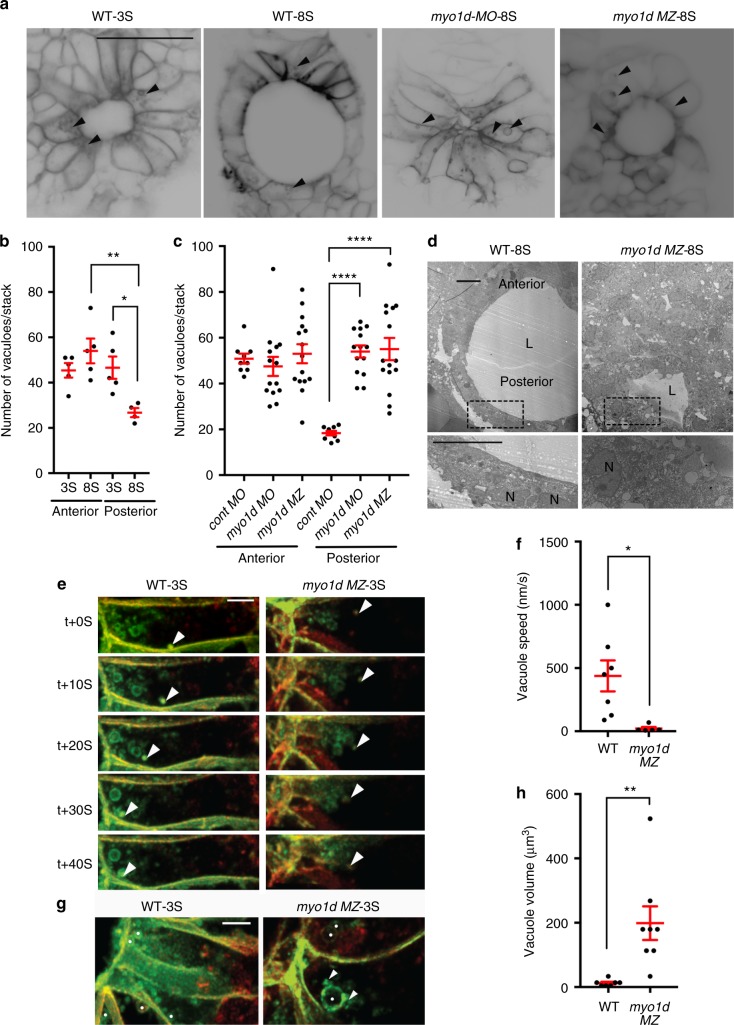

Vacuolar trafficking in KV lumen is disrupted in myo1d mutant

KV lumen formation is a rapid and dynamic process during somitogenesis that spans approximately 3-h period (1S–8S, 10–13 hpf) (Supplementary Movie 1)6. Previous studies described how a symmetric KV rosette undergoes extensive cellular remodeling to become an asymmetric KV so that anterior cells retain columnar shape whereas posterior cells attain squamous or cuboidal shape31. Depletion of Rock2b or pharmacological inhibition of non-muscle myosin II altered anterior–posterior (AP) cell shape changes in the KV21, suggesting that actomyosin activity is important for generating AP asymmetry. Additional fluid filling mechanisms also contribute to this process as chemical inhibition of ion channels, knockdown of cell junction proteins, and mutations in Cftr provide insights into their role in proper KV formation17–20. Thus, we reasoned that myo1d could contribute to the AP asymmetry and lumen expansion through a fluid filling mechanism. In Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) embryos, we observed vacuole-like structures in the KV cells that were designated as such by virtue of their larger size when compared to endocytic or ER-derived vesicles32 (Fig. 3a, and Supplementary Movie 5 & 6). We hypothesized that vacuoles trafficking to the apical surface could be the basis of how the KV lumen expands as these structures provide both membrane and fluid to the epithelium. To quantify this, we counted the number of vacuoles in the KV cells at the beginning and the end of lumen expansion phase (from 3S to 8S). At 3S, vacuoles appeared near the plasma membrane of every KV epithelial rosette cell (Fig. 3a). By 8S, the number of vacuoles was significantly less in posterior cells (Fig. 3a, b). In myo1d MZ mutants and myo1d AUG morphants, we observed an increased number of vacuoles and persistence of columnar shape in the posterior KV epithelial cells at 8S (Fig. 3a, c). Consistently, transmission electron microscopic images revealed an abundance of vacuole-like structures in the myo1d MZ KVs (Fig. 3d). Moreover, Myo1d was co-localized with the vacuoles in KV cells (white arrow, Supplementary Fig. 2a), suggesting Myo1d is involved in trafficking of these vacuoles. Together, these experiments suggest that vacuole clearance contributes to AP cell shape changes in the KV. Next, we used super-resolution imaging to precisely track vacuolar movement from 2S to 3S. The epithelial cells lining KV showed directed vacuolar trafficking toward the rosette apex (Fig. 3e, and Supplementary Movie 7). This vacuolar movement is dynamic such that smaller vacuoles can fuse together as they reach the KV apical membrane (Fig. 3e, & Supplementary Movie 7). On the contrary, myo1d MZ embryos revealed a dispersed, largely cytoplasmic distribution of vacuoles and their movements were misdirected (Fig. 3e). Moreover, the speed of vacuolar movement was decreased in myo1d MZ mutants (Fig. 3e, f, and Supplementary Movie 8). Continuous vacuole fusion events (white arrow Fig. 3g) resulted in larger vacuoles (compare vacuoles marked with white spots in Fig. 3g, and Supplementary Movie 7 & 8). Further, larger vacuoles were predominant in KV epithelial cells of myo1d MZ mutants (Fig. 3h, and Supplementary Movie 9 & 10). Thus, myo1d is required to deliver fluid filled vacuoles to the KV lumen apex. These observations establish the role of myo1d in directed vacuolar movement as a mechanism for KV lumen expansion.

Fig. 3.

myo1d regulate directed vacuolar movement in KV cells. a–c Anterior and posterior KV epithelial cells contain numerous vacuoles (black arrow) at 3S (n = 5 embryos) but decrease in the posterior KV cells at 8S (n = 5 embryos) in Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) embryos (scale bar, 50 µm). Vacuole number in posterior KV cells were increased in myo1d MO injected (n = 14) or in myo1d MZ;Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) mutants (n = 15) when compared to control MO injected embryos (n = 9). Numeration of vacuole number per KV stack are shown in b and c. d TEM showing presence of vacuoles (black arrow) in posterior KV apex in myo1d MZ but not in WT embryos at 8S. L lumen, N nucleus, (n = 4) (scale bar, 10 µm). e–h 4D STED time-lapse still images of a representative KV epithelial cell. Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) KV injected with H2BmCherry mRNA showing directed vacuole migration toward apical surface (white arrow), appeared to fuse with luminal surface. Vacuole movement toward KV apex in the myo1d MZ;Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) mutant were decreased (e). Average vacuole movement speed in KV epithelial cells in myo1d MZ mutants (n = 5 vacuoles from three embryos) were decreased compared to WT (n = 7 vacuoles from three embryos) (f). In myo1d MZ;Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) embryos (n = 7 vacuoles from three embryos), vacuole fusion (shown as white arrow) resulted in increased vacuole size when compared to Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) control (n = 8 vacuoles from three embryos) (g). Vacuoles denoted by white spots. Average vacuole volume was increased in KV epithelial cells (h). Statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis with Turkey’s multiple range tests or unpaired t test. * p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.0001 represents a statistical difference. Data shown are mean ± SEM. Scale bar, 5 µm

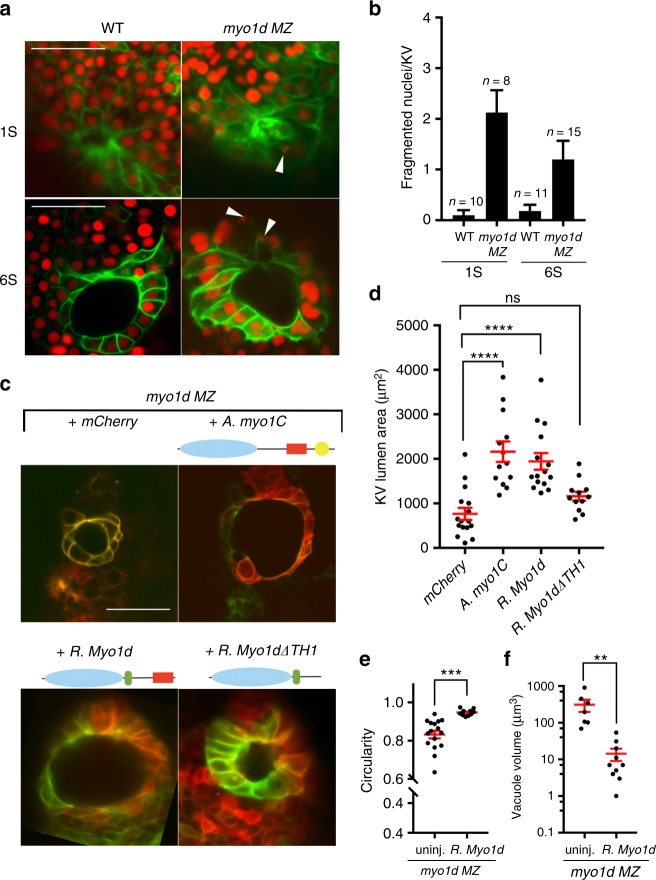

Conservation of Class 1 myosin function in KV morphogenesis

In ancient unicellular eukaryotes, myosin-I is involved in transporting water through contractile vacuoles (CV), which is essential for attaining amoeboid cell shape and regulating directed cell motility33,34. Loss of Acanthamoeba castellanii myosin-IC activity by inhibitory antibodies resulted in CV accumulation in the cell that ultimately leads to cell rupture33. We reasoned that a similar process is occurring in the KV epithelial cells in myo1d MZ mutants. We found a significantly higher number of fragmented nuclei in myo1d MZ embryos compared to wild type at 1S and 6S stage (Fig. 4a, b), suggesting that accumulation of vacuoles may cause KV epithelial cells to burst that may also account for the lower cell number (Supplementary Fig. 4d, e). All unconventional Myosin I class proteins contain a Myosin motor at the N-terminus, and a Myosin Tail-Homology 1 (TH1) domain at the C-terminus35. Other structural domains that are shared within this class of proteins include calmodulin binding IQ motifs and SH3 domains (Supplementary Fig. 5a)35. We used Phyre2 to predict the motor and TH1 protein structures as conservation between zebrafish Myo1d and amoeba myosin-1C were lower than the vertebrate Myosins (Supplementary Fig. 5a)36. Both the motor and TH1 domains (Supplementary Fig. 5b) from these species show similar predicted structures suggesting that they could serve similar functions. Hence, we postulated that the Amoeba myosin-1C could compensate for the loss of myo1d in zebrafish. Overexpression of Acanthamoeba myosin-IC artificially expanded KV lumen in wild-type embryos (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d), indicating that myosin-IC derived from Amoeba is functional in zebrafish KV cells. Moreover, injection of Acanthamoeba myosin-IC mRNA into myo1d MZ embryos rescued KV lumen and AP cell morphology defects as efficiently as a phylogenetically closer version of Myosin 1d derived from rat (Fig. 4c, d). Rescue of circularity, reduction of vacuole volume, and laterality from ectopic expression of rat Myo1d was also observed in Myo1d-deficient embryos (Fig. 4e, f and Supplementary Fig. 1g). These results suggest that vacuole delivery is important for lumen expansion and myo1d is essential for this process. All Myosin I molecules contain a TH1 domain that binds to lipid membranes35,37. To further understand if TH1 domain in Myo1d is required for KV lumen formation, we injected rat Myo1d lacking the TH1 domain (Myo1d∆TH1) into myo1d MZ mutants and observed a failure of KV lumen size rescue (Fig. 4c, d). These results indicate that myo1d is essential component for KV morphogenesis and function.

Fig. 4.

Conservation of Myosin I protein function. a, b Loss of myo1d results in increased nuclear fragmentation. Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) or myo1d MZ; Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA) embryos injected with H2BmCherry mRNA exhibit fragmented nuclei in KV epithelial cells and quantified as fragmented nuclei per KV sample. Fragmented nuclei are represented as absolute numbers per KV Z-section. c–f Overexpression of amoeba myo1C (n = 13) or rat Myo1d (n = 15) were sufficient to rescue lumen area in myo1d MZ embryos compared to uninjected controls (n = 16) (d), circularity (n = 16 myo1d MZ, n = 10 rat Myo1d injected MZ embryos) (e), and reduced vacuole size (n = 9 myo1d MZ, n = 10 rat Myo1d injected MZ embryos) (f) in myo1d MZ mutants. However, rat Myo1d lacking the TH1 domain (myo1d∆TH1) (n = 12) failed to restore lumen size (d). Unpaired t test or one-way ANOVA with post hoc Turkey’s multiple range tests were conducted with, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.0001 represents statistical significance. ns not significant. Data shown are mean ± SEM

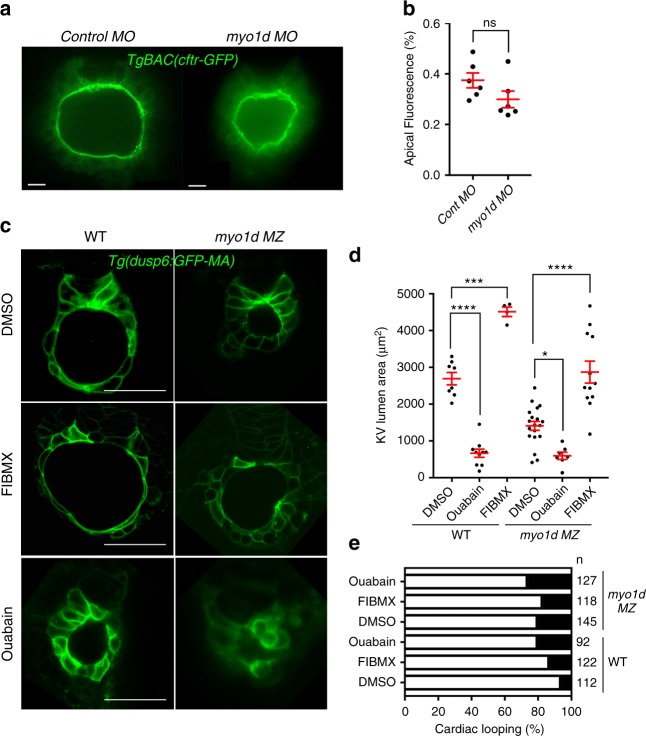

Cftr functions independently of Myo1d in the KV

Cftr, which is localized in KV apical membranes, was shown to regulate water transport into the epithelial lumen38. Consistently, zebrafish Cftr mutants exhibited impaired KV lumen formation19, while activating Cftr with Forskolin and IBMX (FIBMX) expanded KV lumen size20. Myo1a is required for Cftr brush border membrane trafficking and ion transport in the mouse intestine epithelium39. So, we wondered whether Cftr in KV apical surface is regulated through myo1d in zebrafish. This mechanism could also account for the smaller KV lumen in myo1d MZ mutants. For this, we quantified Cftr trafficking to the KV apical surface using the TgBAC(Cftr-GFP) embryos, where Cftr is fused to GFP19. We observed normal Cftr localization in the KV apical membrane after Myo1d depletion (Fig. 5a, b). Interestingly, FIBMX treatment in myo1d MZ embryos showed expansion of KV lumen, implicating Cftr mediated lumen expansion was still functional in the absence of Myo1d (Fig. 5c, d). However, FIBMX treatment in myo1d MZ mutants failed to restore circular KV shape and cardiac looping (Fig. 5e). We next determined if in the absence of Myo1d, suppressing Na+/K+-ATPases would have an additive effect on lumen size. The ion gradient driving Cftr activity is generated by Na+/K+-ATPases in the KV19,20. Embryos treated with ouabain, a potent specific Na+/K+- ATPase inhibitor, blocks Cftr function and decreases KV lumen size19. Ouabain treatment decreased lumen volume in control and to a lesser extent in myo1d MZ mutants embryos (Fig. 5c–e). Similarly, ouabain treatment increased incidence of cardiac looping defects in wild-type embryos (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 6). This is consistent with a previous observation that reported increasing laterality defects with a high dose of ouabain treatment40. However, ouabain treatment on myo1d MZ mutants had no additive effect on laterality defects (Fig. 5e). Thus, proper KV lumen formation with a spherical shape and threshold volume requires multiple modes of fluid filling mechanisms that is coordinated to expand KV lumen within a short developmental time.

Fig. 5.

Modulating Cftr activity restores lumen size in myo1d MZ mutant embryos. a, b Knockdown of myo1d in TgBAC(Cftr-GFP) embryos did not affect CFTR apical GFP localization (n = 6 control MO, n = 6 myo1d MO). c–e Activation of Cftr function in the absence of myo1d MZ mutant expanded lumen area. Representative Z-stack image showing that Forskolin and IBMX (FIBMX) increased KV lumen in WT and myo1d MZ embryos (c). Treating with ouabain, an inhibitor of Na+/K+ ATPase decreased the KV lumen area in WT and myo1d mutant embryos. Numeration of lumen area with treatments are shown in (WT-DMSO: n = 8, WT-ouabain: n = 10, WT-FIBMX: n = 4, myo1d MZ-DMSO): n = 19, myo1d MZ-ouabain: n = 7, myo1d MZ-FIBMX: n = 12) (d). Cardiac looping defects were increased in WT embryos treated with FIBMX or ouabain but did not increase in myo1d MZ mutants (e). Unpaired t test and one-way ANOVA were conducted. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 represents statistical significance. ns not significant. Data shown are mean ± SEM. L lumen, scale bar = 15 µm (a), 50 µm (c)

Discussion

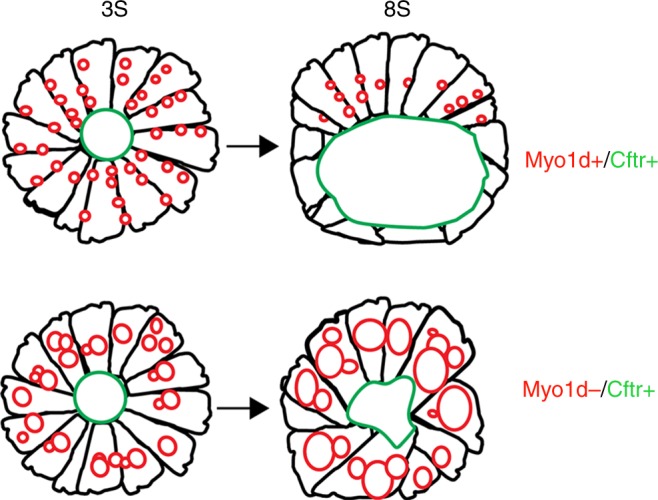

How does Myo1d regulates laterality in different model systems? In Drosophila, tissue specific and temporal expression of myosin1D in the hindgut was sufficient to drive intrinsic chirality at the cellular level that generates a consistent gut and gonad looping pattern11. A mechanical model suggests that anchored myosin motors walking along actin drives the filaments to turn in leftward circles41. With no LRO in invertebrates, these circular forces drive specific organ looping morphogenesis11,12. On the contrary, in zebrafish, myo1d provides the forces required for vacuole delivery and generation of AP cell shape rearrangement of KV. In addition, vacuole delivery by Myo1d can also provide plasma membrane for luminal surface that is required for cell shape morphology. This lack of plasma membrane delivery to the lumen could explain how definitive LRO shape fails to form in myo1d MZ mutants. Irregularity in KV shape likely contributes to the failure of unidirectional flow in the myo1d MZ mutants and increase the frequency of laterality defects. Also, during KV lumen expansion phase, AP cell shape arrangement is critical for asymmetric distribution of cilia31. Thus, defective epithelial cell arrangement in myo1d MZ mutant KVs can affect AP cilia arrangement and flow. While our manuscript was in review, two studies report that Myo1d is required for proper cilia orientation in the LRO through interaction with the planar cell polarity pathway as the reason for laterality defects42,43. This ciliary orientation defect contributes to disruption of unidirectional flow in the LRO (Fig. 2e, f)42. Our studies propose that Myo1d is required for proper KV morphogenesis and lumen formation. We reason that in the absence of this process, the proper orientation of motile cilia would likely be affected and supports these recent findings. Taken together, our results indicate that myosin motor protein found in primitive eukaryotes that is critical for LRO morphogenesis and determining LR asymmetry in vertebrates.

Although KV cell volume changes occur in concert with KV remodeling processes during lumen formation, multiple mechanisms may be involved in coordinating cell shape and threshold size of lumen by 8S stage. In support of this hypothesis, inhibiting Rock2b function or non-muscle myosin II activity had no effect on KV lumen expansion but prevented cell shape changes during KV remodeling21. On the other hand, Cftr, Na+/K+-ATPase ion channels and tight junction proteins regulate KV epithelial cell shape, and cell volume that impinge on proper KV lumen expansion17–20. In addition to these mechanisms, we propose that myo1d-mediated vacuolar transport is required for regulating KV epithelial cells, and lumen shape to attain a threshold volume in a limited developmental timeframe (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

myo1d functions to regulate KV lumen expansion, a key event in establishing proper laterality in zebrafish. A model depicting the role of Myo1d and Cftr in KV lumen expansion. When Myo1d mediated vacuole delivery and Cftr channel are active, proper AP cell morphology and threshold lumen expansion with a definitive spherical shape are established by 8S. In the absence of Myo1d, despite CFTR channel being present, KV lumen fails to generate a spherical shape and proper size. This is due to the failure of vacuole trafficking towards apical surface of the KV

During lumen expansion, it appears that KV fluid is primarily derived from posterior epithelial cells that decrease cell volume concomitant with lumen expansion17. It is remarkable that this process is akin to the water expulsion mechanism found in protozoans that traffic water and other fluid filled contractile vacuoles to the plasma membrane33. Similar asymmetrical fluid loss and epithelial thinning process were observed during zebrafish OV development where actomyosin interaction provides the forces necessary to expand OV lumen44. Consistently, this remodeling process creates new luminal space and cause a net redistribution of fluid from epithelial cells into the lumen, highlighting the role of intra epithelial fluid in lumen expansion44. We also observed lumen formation defects in the OV of myo1d MZ mutants, suggesting that myo1d mediated vacuole trafficking could be a common mechanism for determining lumen shape and size during formation of fluid-filled structures in development.

Methods

Zebrafish handling and maintenance

All the experiments using zebrafish was carried out with prior review and approval by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Transgenic zebrafish lines used in work were: Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA)pt21, AB*, myo1d TALEN mutant lines generated for this work were labeled: pt31a, pt31b, and pt31c alleles.

Morpholino injections and rescue experiments

Antisense Morpholino (MOs) were obtained from Gene-tools LLC. MOs were designed against translation initiation codon (5′-CCAAACTTTCGTGTTCTGCCATAAT-3′) of zebrafish myo1d. MOs were injected into embryos at 2-cell stage as previously reported45. To conduct rescue experiments, full length rat MYO1D was PCR amplified and cloned into pCS2+ vector. Rat Myo1D TH1 deletion construct (Myo1d ΔTH1) was generated by primers forward (5′-gccatgtagatgTTGAAAGGTCAAAGGGCAGAC-3′) reverse (5′-tgcaacctttgcCCTGACCTGGGGAAGGTC-3′) designed to anneal full length rat MYO1D construct. Amplicons were generated and Kinase-Ligase-DpnI (KLD) treated using Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (NEB#E0554S). Rat Myo1d ΔTH1 were designed to insert a STOP codon at the start site of TH1 domain. Acanthamoeba sp myosin-1C33 was cloned into pCS2+ vector between Nco1 and Xba1 restriction site. Linearized pCS2+ vector was used to generate mRNA using SP6 mMessage mMachine (Ambion: AM1340) and purified using Roche mini quick spin RNA columns (Roche: 11814427001, USA).

Design of TALEN DNA binding domains

The software developed by the Bogdanove laboratory (https://boglab.plp.iastate.edu/node/add/talen) was used to find best DNA binding sites to target myo1d exon2 as described21. TALEN-binding sites were 18 (Random variable repeats) RVDs (NI HD HD NH NG NH HD HD NI NG NH NI NI HD NI NG NG NG) on the left-TALEN and 19 RVDs (HD NG NH HD HD NG NG NG NH NG NI HD NG NH HD NG HD NI NI) on the right-TALEN with 15 bases of spacer.

Construction of goldy TALENs and mutant generation

TALEN assembly of the RVD-containing repeats was conducted using the Golden Gate approach31. Once assembled, the RVDs were cloned into a destination vector, pT3TS-GoldyTALEN. After sequence confirming RVDs were in frame with destination vector, linearized plasmids were used to generate mRNAs using SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion: AM1340) and purified using Roche mini quick spin RNA columns (Roche: 11814427001, USA). Each mRNA TALEN pairs were co-injected into 1-cell stage embryos and raised to adults. Somatic and heritable TALEN induced mutations were evaluated by using forward (myo1d-F1: 5′-TTGCTGCAGGTTTGAAAAGGGTCGTA-3′) and reverse (myo1d-R1: 5′-CAGTCTACCTGAGATGACAATGCACG-3′) using primers and One Taq DNA polymerase (NEB: MO0480S). PCR was performed using following cycling conditions: initial denaturation 4 min 95 °C, 35 cycles (30S 95 °C, 30S 58 °C, 30S 68 °C) and final extension 5 min 68 °C. A 226 bp PCR amplicon generated from 48 hpf embryos were used to detect disruption of AatII restriction site in the myo1d target site by restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Founders harboring mutant alleles were outcrossed to generate F1 population and sequence verified. Positive F1 heterozygotes were in-crossed to generate homozygous zygotic (Z) mutants. Maternal zygotic (MZ) mutants are generated by in-crossing homozygous parents.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Total RNA was isolated from zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf. Total RNA (1 µg) was reverse transcribed with Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and amplified with the primers: 5′-AACGTTCCTCCTTGCCCTGTAATC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCTATAATGTGACCGGAGTGAGCA-3′ (reverse). PCR products of myo1d mRNA and inserted into PCRII-TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific: K465001). Sequence confirmed clones were used to make myo1d riboprobes. Following riboprobes prepared using the cDNA constructs for myl746, spaw47 foxa348, foxj1a28, dand549, ntla40, and myod140 with digoxygenin RNA labelling kit (Roche DIG RNA Labeling Kit: 11175025910). In situ RNA hybridizations in whole-mount zebrafish embryo were performed at desired stages using standard zebrafish protocols50. For dand5 quantification, right to left ratio for 8S stage embryos in WT and myo1d MZ were calculated using ImageJ. dand5 insitu expression domains on either side of embryonic midline were measured after fitting a region of interest. Further, a ratio of right- vs left-sided expression region were derived to asses if KV function is compromised. This protocol was adapted from ref.51 to describe KV function.

Immunohistochemistry and microscopy

Primary antibodies used for this study: acetylated tubulin (Sigma T7451: 1:500), Myosin 1d (Abcam ab70204: 1:400), and atypical PKC (Santa Cruz sc-216: 1:200). Secondary antibodies were anti mouse-Alexa 594 (Invitrogen A11005: 1:500) and rabbit-Alexa 488 (Invitrogen A11008: 1:500). Embryos were fixed in 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight and then dechorionated in 1× PBS. Embryos were permeabilized in 1× PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100 and treated with blocking solution containing 1× PBS, 10% sheep serum, 1% DMSO, and 0.1% Triton X for an hour. Primary antibodies were diluted in fresh blocking buffer and incubated with embryos for at 4 °C overnight and then washed in 1× PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100 (3× washes, 30 min each) at room temperature.

KV imaging and analysis

Tg(dusp6:GFP-MA)pt21 transgenic embryos at 2–3S were maintained at 28.5 °C and mounted on a transparent (MatTek: P35G-1.0-20-C) glass bottom culture dish in 1.5% low melting agarose. For Cftr expression analysis, KV was imaged in live TgBAC(Cftr-GFP) embryos using a Perkin-Elmer UltraVIEW Vox spinning disk confocal microscope with ×40 water immersion objective. Imaris (Bitplane) and Fiji (ImageJ NIH, Bethesda, MD) software was used to measure raw integrated density of the total KV area or the apical membrane region. The apical signal was then divided by the total signal to determine the apical intensity as a percentage of total fluorescence to control for differences in KV size or transgene expression levels. For four-dimensional (4D) time-lapse imaging, we used stimulation emission depletion (STED) imaging with Leica 93 × 1.3 NA motorized correction collar objective. Z stacks with 200 nm step size imaged for 10 min with 8 s intervals and were deconvolved with Huygens Professional version 17.04 (Scientific Volume Imaging, The Netherlands) in order to improve signal to noise ratio. All the measurements on speed and volume of vacuole was done manually from 4D STED images using Fiji. Vacuole volume measurements from confocal and STED images were derived from diameter, so only spherical structures were considered for measurement. To measure circularity, the largest Z stack from KV images were used to measure area and perimeter and calculate the circularity values using the formula: (see ref.25 for a more detailed description of this method to calculate circularity).

KV flow analysis

Embryos were removed from chorions mounted in 1.5% low melt agarose in system water in Mattek glass bottom Petri dishes. FITC fluorescent beads (0.2 μm) (Polysciences) were pressure injected into KV at the eight-somite stage. Intact embryos after injection were remounted and imaged on a Nikon (Melville NY) Tie microscope with a high NA (1.15) ×40 LWD water objective52. Movies were made after collecting 2000 frames at 100 frames/s with a Photometrics 95B back-thinned sCMOS camera. Particle tracking was performed using Imaris (Bitplane) software.

Transmission electron microscopy

In total, 8S embryo samples were fixed overnight using cold 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.01 M PBS. Fixed samples were washed 3× in PBS then post fixed in aqueous 1% OsO4, 1% K3Fe(CN)6 for 1 h. Following three PBS washes, the pellet was dehydrated through a graded series of 30–100% ethanol, 100% propylene oxide then infiltrated in 1:1 mixture of propylene oxide: Polybed 812 epoxy resin (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) for 1 h. After several changes of 100% resin over 24 h, pellet was embedded in molds for cross-sectioning embryos, cured at 37 °C overnight, followed by additional hardening at 65 °C for two more days. Ultrathin (70 nm) sections were collected on 200 mesh copper grids, stained using a Leica EM AC20 automatic grid staining machine with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 45 min, followed by Reynold’s lead citrate for 7 min. Sections were imaged using a JEOL JEM 1011 transmission electron microscope (Peabody, MA) at 80 kV fitted with a side mount AMT digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA).

Pharmacological treatment

Stock solutions of 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 100 mM IBMX (Sigma# 410957), 10 mM Forskolin (Sigma# F3917), and 10 mM Ouabain (Cat #O 0200000) were prepared in DMSO. Embryos were treated with a working concentration of 10 μM Forskolin and 40 μM IBMX or 1 and 5 μM Ouabain in E3 egg water from bud stage until 8S.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance using unpaired t test or one-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis using Turkey’s multiple range test by Graphpad Prism (Graph pad, La Jolla, CA, USA).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary information files). In addition, data from this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Korn (National Institute of Health, MD) for sharing Acanthamoeba sp. myosin-IC plasmid construct, S. Wolfe and N. Lawson (University of Massachusetts, MA) for their suggestions on myo1d targeting strategies, C. Stuckenholz and L. Davidson (Department of Bio Engineering) for sharing pCS2 CAAX and H2B: mCherry plasmid construct, and K. Alber (Center for Biological Imaging) at University of Pittsburgh, PA for help with tracking of vacuolar movement in time lapse images. This work was supported by NIH Grant 5R01GM104412 to M.T. and C.W.L. STED imaging instrument used for this work at CBI core facility was supported through NIH Grant S10 OD021540.

Author contributions

C.W.L., H.Y., M.S., and M.T. initiated the project concept. H.Y. and M.S. generated plasmid constructs. M.S. and M.T. generated zebrafish myo1d mutants and analyzed phenotypes. M.S., M.J.C., J.D.A., and M.T. performed morpholino experiments. M.S., T.F., M. Sun, and D.B.S. performed confocal, and TEM imaging and analysis. M.S., M.C., and S.C.W. performed super-resolution 4D STED and KV flow imaging and analysis. M.S. and M.T. analyzed all the data, prepared figures, and drafted the manuscript. M.T., J.D.A., and C.W.L. edited the manuscript. All the authors have read the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/6/2018

This Article was originally published without the accompanying Peer Review File. This file is now available in the HTML version of the Article; the PDF was correct from the time of publication.

Contributor Information

Manush Saydmohammed, Email: mas386@pitt.edu.

Michael Tsang, Email: tsang@pitt.edu.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-05866-2.

References

- 1.Vandenberg LN, Levin M. A unified model for left-right asymmetry? Comparison and synthesis of molecular models of embryonic laterality. Dev. Biol. 2013;379:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown NA, Wolpert L. The development of handedness in left/right asymmetry. Development. 1990;109:1–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aw S, Adams DS, Qiu D, Levin M. H,K-ATPase protein localization and Kir4.1 function reveal concordance of three axes during early determination of left-right asymmetry. Mech. Dev. 2008;125:353–372. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephen LA, et al. Failure of centrosome migration causes a loss of motile cilia in talpid(3) mutants. Dev. Dyn. 2013;242:923–931. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basu B, Bruedner M. Cilia: multifunctional organelles at the center of vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2008;85:151–174. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00806-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Essner JJ, Amack JD, Nyholm MK, Harris EB, Yost HJ. Kupffer’s vesicle is a ciliated organ of asymmetry in the zebrafish embryo that initiates left-right development of the brain, heart and gut. Development. 2005;132:1247–1260. doi: 10.1242/dev.01663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweickert A, et al. Cilia-driven leftward flow determines laterality in Xenopus. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGrath J, Somlo S, Makova S, Tian X, Brueckner M. Two populations of node monocilia initiate left-right asymmetry in the mouse. Cell. 2003;114:61–73. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00511-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okada Y, Takeda S, Tanaka Y, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Hirokawa N. Mechanism of nodal flow: a conserved symmetry breaking event in left-right axis determination. Cell. 2005;121:633–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui C, Little CD, Rongish BJ. Rotation of organizer tissue contributes to left-right asymmetry. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 2009;292:557–561. doi: 10.1002/ar.20872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taniguchi K, et al. Chirality in planar cell shape contributes to left-right asymmetric epithelial morphogenesis. Science. 2011;333:339–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1200940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuroda R, Endo B, Abe M, Shimizu M. Chiral blastomere arrangement dictates zygotic left-right asymmetry pathway in snails. Nature. 2009;462:790–794. doi: 10.1038/nature08597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hozumi S, et al. An unconventional myosin in Drosophila reverses the default handedness in visceral organs. Nature. 2006;440:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature04625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Speder P, Adam G, Noselli S. Type ID unconventional myosin controls left-right asymmetry in Drosophila. Nature. 2006;440:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature04623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryant DM, Mostov KE. From cells to organs: building polarized tissue. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:887–901. doi: 10.1038/nrm2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amack JD, Wang XH, Yost HJ. Two T-box genes play independent and cooperative roles to regulate morphogenesis of ciliated Kupffer’s vesicle in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 2007;310:196–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasgupta, A. et al. Cell volume changes contribute to epithelial morphogenesis in zebrafish Kupffer’s vesicle. Elife7, pii: e30963 (2018). 10.7554/eLife.30963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Kim JG, Bae SJ, Lee HS, Park JH, Kim KW. Claudin5a is required for proper inflation of Kupffer’s vesicle lumen and organ laterality. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0182047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navis A, Marjoram L, Bagnat M. Cftr controls lumen expansion and function of Kupffer’s vesicle in zebrafish. Development. 2013;140:1703–1712. doi: 10.1242/dev.091819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roxo-Rosa M, Jacinto R, Sampaio P, Lopes SS. The zebrafish Kupffer’s vesicle as a model system for the molecular mechanisms by which the lack of Polycystin-2 leads to stimulation of CFTR. Biol. Open. 2015;4:1356–1366. doi: 10.1242/bio.014076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cermak T, et al. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang P, et al. Heritable gene targeting in zebrafish using customized TALENs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:699–700. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller JC, et al. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:143–148. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Missinato, M. A. et al. Dusp6 attenuates Ras/MAPK signaling to limit zebrafish heart regeneration. Development145 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Pantic I, et al. Chromatin fractal organization, textural patterns, and circularity of nuclear envelope in adrenal zona fasciculata cells. Microsc. Microanal. 2016;22:1120–1127. doi: 10.1017/S1431927616011910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gokey JJ, Ji Y, Tay HG, Litts B, Amack JD. Kupffer’s vesicle size threshold for robust left-right patterning of the zebrafish embryo. Dev. Dyn. 2016;245:22–33. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cartwright JHE, Piro O, Tuval I. Fluid-dynamical basis of the embryonic development of left-right asymmetry in vertebrates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7234–7239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402001101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hellman NE, et al. The zebrafish foxj1a transcription factor regulates cilia function in response to injury and epithelial stretch. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18499–18504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005998107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto H, et al. The Cerberus/Dan-family protein Charon is a negative regulator of Nodal signaling during left-right patterning in zebrafish. Development. 2004;131:1741–1753. doi: 10.1242/dev.01070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hirokawa, N., Tanaka, Y. & Okada, Y. Left-right determination: involvement of molecular motor KIF3, cilia, and nodal flow. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 1 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Bedell VM, et al. In vivo genome editing using a high-efficiency TALEN system. Nature. 2012;491:114–118. doi: 10.1038/nature11537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMahon HT, Boucrot E. Molecular mechanism and physiological functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:517–533. doi: 10.1038/nrm3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doberstein SK, Baines IC, Wiegand G, Korn ED, Pollard TD. Inhibition of contractile vacuole function in vivo by antibodies against myosin-I. Nature. 1993;365:841–843. doi: 10.1038/365841a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Betapudi V, Egelhoff TT. Roles of an unconventional protein kinase and myosin II in amoeba osmotic shock responses. Traffic. 2009;10:1773–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu Q, Li JC, Ye F, Zhang MJ. Structure of myosin-1c tail bound to calmodulin provides insights into calcium-mediated conformational coupling. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:81–88. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, Sternberg MJE. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:845–858. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams RJ, Pollard TD. Binding of myosin I to membrane lipids. Nature. 1989;340:565–568. doi: 10.1038/340565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riordan JR. CFTR function and prospects for therapy. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:701–726. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kravtsov DV, et al. Myosin Ia is required for CFTR brush border membrane trafficking and ion transport in the mouse small intestine. Traffic. 2012;13:1072–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Compagnon J, et al. The notochord breaks bilateral symmetry by controlling cell shapes in the zebrafish laterality organ. Dev. Cell. 2014;31:774–783. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tee YH, et al. Cellular chirality arising from the self-organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:445–457. doi: 10.1038/ncb3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Juan, T. et al. Myosin1D is an evolutionarily conserved regulator of animal left–right asymmetry. Nat. Commun.9,1–12 (2018). 10.1038/s41467-018-04284-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Tingler M, et al. A conserved role of the unconventional myosin 1d in laterality determination. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:810–816. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoijman E, Rubbini D, Colombelli J, Alsina B. Mitotic cell rounding and epithelial thinning regulate lumen growth and shape. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7355. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsang M, et al. A role for MKP3 in axial patterning of the zebrafish embryo. Development. 2004;131:2769–2779. doi: 10.1242/dev.01157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Znosko WA, et al. Overlapping functions of Pea3 ETS transcription factors in FGF signaling during zebrafish development. Dev. Biol. 2010;342:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Long S, Ahmad N, Rebagliati M. The zebrafish nodal-related gene southpaw is required for visceral and diencephalic left-right asymmetry. Development. 2003;130:2303–2316. doi: 10.1242/dev.00436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Field HA, Ober EA, Roeser T, Stainier DY. Formation of the digestive system in zebrafish. I. Liver morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2003;253:279–290. doi: 10.1016/S0012-1606(02)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuan SL, Zhao L, Brueckner M, Sun ZX. Intraciliary calcium oscillations initiate vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:556–567. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thisse C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Superina S, Borovina A, Ciruna B. Analysis of maternal-zygotic ugdh mutants reveals divergent roles for HSPGs in vertebrate embryogenesis and provides new insight into the initiation of left-right asymmetry. Dev. Biol. 2014;387:154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang ZY, Wang F, Sellers JR, Korn ED, Hammer JA., 3rd Analysis of the regulatory phosphorylation site in Acanthamoeba myosin IC by using site-directed mutagenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:15200–15205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary information files). In addition, data from this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.