Abstract

Microbiomes influence plant establishment, development, nutrient acquisition, pathogen defense, and health. Plant microbiomes are shaped by interactions between the microbes and a selection process of host plants that distinguishes between pathogens, commensals, symbionts and transient bacteria. In this work, we explore the microbiomes through massive sequencing of the 16S rRNA genes of microbiomes two Marchantia species of liverworts. We compared microbiomes from M. polymorpha and M. paleacea plants collected in the wild relative to their soils substrates and from plants grown in vitro that were established from gemmae obtained from the same populations of wild plants. Our experimental setup allowed identification of microbes found in both native and in vitro Marchantia species. The main OTUs (97% identity) in Marchantia microbiomes were assigned to the following genera: Methylobacterium, Rhizobium, Paenibacillus, Lysobacter, Pirellula, Steroidobacter, and Bryobacter. The assigned genera correspond to bacteria capable of plant-growth promotion, complex exudate degradation, nitrogen fixation, methylotrophs, and disease-suppressive bacteria, all hosted in the relatively simple anatomy of the plant. Based on their long evolutionary history Marchantia is a promising model to study not only long-term relationships between plants and their microbes but also the transgenerational contribution of microbiomes to plant development and their response to environmental changes.

Introduction

All multicellular eukaryotes have a microbiome composed of prokaryotes, primarily bacteria, and eukaryotes, both uni- and multicellular. Species of the microbiome can be commensal, pathogenic, symbiotic, essential, or neutral. Land plants are no exception, with three distinct habitats colonized by microbial species — the rhizosphere underground and at the substrate surface, the phyllosphere on the aerial plant surfaces, and the endosphere within the plant body1–3. Land plants evolved from a freshwater algal ancestor and upon the transition to terrestrial habitats was exposed to novel microbial communities. It has long been recognized that early, and perhaps the first, land plants harbored mycorrhizal fungi, perhaps in a symbiotic relationship from the onset4. Furthermore, it has been suggested that early land plants may have inherited a microbiome from their algal ancestor, perhaps consisting of nitrogen-fixing bacterial and methanotrophs5.

Extant land plants consist of bryophytes (liverworts, mosses, hornworts), a monophyletic or paraphyletic group of gametophyte dominant plants and the monophyletic vascular plants. Bryophytes are largely poikilohydric — their water potential is equilibrated rapidly to external water availability. Their gametophyte bodies are in close contact with the substrate surface and ventral rhizoids act in water absorption and distribution. In contrast, the diploid sporophyte dominant vascular plants are homoiohydric, with a root system through which water is obtained. Early land plants established symbiotic associations with mycorrhizae, and it is thought that Palaeozoic drops in CO2 reduced phosphate (P) absorption in non-vascular plants which in addition to competition for light favoured the vascular plants Earth dominance6.

Extensive sequencing approaches have fostered recent studies on plant-microbe interactions, and plant microbiomes from model plants like Arabidopsis thaliana and agriculturally relevant species are publicly available7–10, and these have contributed to the study of plant-microbe interactions. Proposed models for the establishment of the plant root microbiome include the two-step model that considers the root microbiome as a product of plant-independent features. The two-step model considers edaphic factors, the general selection of microorganisms for general plant cell wall composition, rhizodeposits and the host genotype which actively selects their microbial inhabitants11. While considerable knowledge of vascular plant microbiomes is available, much less is known about the microbiomes of bryophytes, and knowledge is largely limited to mycorrhizal and other fungal interactions.

In contrast to vascular plants that possess roots that penetrate deeply into the soil, sometimes meters, bryophytes adhere to the substratum via rhizoids, unicellular (liverworts, hornworts) or multicellular (mosses) filaments that penetrate only the top few millimeters of the substratum. Despite these differences, the rhizoids and ventral tissues of liverworts and hornworts are colonized by mycorrhizal fungi in a similar manner as the roots hairs and root tissues of vascular plants4, reviewed in12,13. In addition to mycorrhizal fungi, pathogenic fungi infecting all three lineages bryophytes have been described in some detail reviewed in2. Less is known about the broader fungal microbiomes of bryophytes, however, a recent survey of fungal inhabitants of the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha in a variety of habitats revealed a diversity of fungi, some of which are pathogenic and others of which could promote growth of the liverwort host14.

In contrast to fungal components of bryophyte microbiomes, less is known about the bacterial communities inhabiting bryophytes. One exception is the well-characterized symbiotic colonization of slime cavities of hornwort thalli and ventral structures of the liverworts Blasia and Cavicularia by nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterial Nostoc colonies15–17. Recently, a few broad surveys of several bryophyte species has begun to provide insight into their broader bacterial microbiomes and have hinted at a diverse microbiome including some potential nitogen-fixing bacteria5,18–21.

Among liverworts, species within the genus Marchantia have become model genetic systems to investigate fundamental questions in evolutionary biology. Liverwort with a similar morphology have existed since the Permian22 possibly allowing ancient microbial associations to persist. Species of the liverwort genus Marchantia are cosmopolitan, inhabiting most of the terrestrial planet and can colonizing a large number of habitats including stream banks, rocks surfaces, logs, and also growing as epiphytes on trees23. M. polymorpha has attracted the attention of naturalists and scientists as a model system since the 18th century, with Marchantia pivotal to the study of sexual chromosomes in plants, sex determination, the cellular nature of organisms and to the study of the establishment of dorsoventral body plans and polarity24. The M. polymorpha subsp. ruderalis genome was the first liverwort genome sequenced24–26.

While Marchantia polymorpha subsp. ruderalis has not been observed to establish mycorrhizal fungal interactions, they have been observed in M. polymorpha subsp. montivagans and other Marchantia species, such as M. paleacea and M. foliacea13,27–29. Recently, fungal endophytes from wild populations of M. polymorpha were isolated and found their interactions with the host plant under in vitro conditions could be pathogenic, commensal or beneficial14. Again, less is known about the bacterial inhabitants of Marchantia. A handful of reports on culturable bacteria isolated from Marchantia thalli identified Methylobacterium as a likely commensal30,31. A study of the bacterial microbiome of M. inflexa in three different habitats (streamside, roadside, and greenhouse) found habitat-specific microbiome diversity, with the wild habitats harboring more similar microbiomes than that found under greenhouse conditions21. Interestingly, there are reports of M. polymorpha extracts able to inhibit bacterial growth32, suggesting an active microbial selection of its microbial guests.

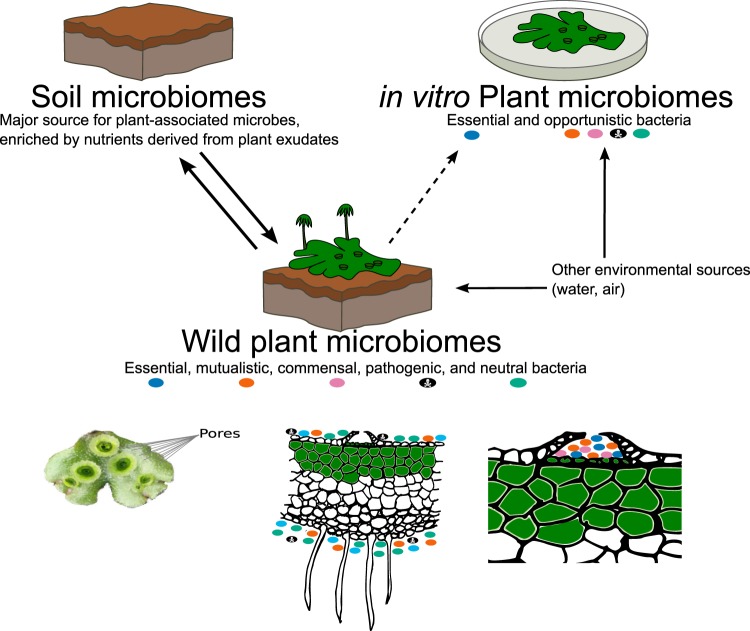

In this work we attempt to understand the richness and diversity of two Marchantia species microbial inhabitants in plants from the wild and plants established under in vitro conditions33 (Fig. 1). One species, M. polymorpha subsp. ruderalis is a rapid colonizer of disturbed habitats34 that does not form mycorrhizal associations. The second species, M. paleacea, is an ecological ‘stayer’ forming stable colonies with mycorrhizal associations. The plant’s microbiome, specifically the root-associated microbiome has been shown to have dramatic effects on plants establishment, survival, and access to nutrients11. Given their anatomical structure, profiling microbiomes from Marchantia’s thalli (also containing single cell rhizoids) would be the equivalent of microbiome profiles obtained from both root and phyllosphere in vascular plants.

Figure 1.

Marchantia microbiomes are the product of soil microbiomes and other environmental sources. Most bacteria in a plant microbiome are introduced to their soil as minor contributors from other environmental sources, such as rain and wind propagated microbes. Essential bacteria should be present in microbiomes from Marchantia grown in both the wild and in vitro conditions. By comparing M. paleacea and M. polymorpha under wild and in vitro conditions, we aimed to identify key plant-associated bacteria.

Results and Discussion

Marchantia microbiome richness and diversity

A total of 164,385 Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs; 97% identity 16S rRNA gene identity) were assigned to the whole dataset encompassing wild populations of M. polymorpha and M. paleacea, their source soils, and in vitro grown plants for both Marchantia species. After removal of chimeras, singletons, mitochondrial, and chloroplasts sequences, the whole dataset was reduced to 36,299 high-quality representatives OTUs that was the dataset used for this study. Marchantia paleacea under wild conditions recruited more OTUs (Mpala = 10,070) than wild M. polymorpha (Mpoly = 6,188) (see Table 1). Both soils of wild M. paleacea and M. polymorpha show similarly observed OTU numbers (Mpala = 8,367; Mpoly = 8,313). The in vitro grown Marchantia species showed a pattern opposite from their wild relatives, where M. polymorpha (1,162) recruited 2.89 more OTUs than M. paleacea (402). The nonparametric Chao1 index35–37 estimated an expected number of OTUs based on the number of low abundance OTUs. We used the Chao1 as a reference to determine the gap between our observed OTUs and a theoretical maximum. We observed fair sequencing coverage when comparing the observed OTUs against Chao1 Index with up to 89% of the wild Marchantia OTUs, up to 90% of soil OTUs coverage (M. polymorpha’s soil), and up to 99% of the in vitro grown Marchantia OTUs. Shannon’s index indicated that Marchantia wild species were diverse (Mpala = 8.29; Mpoly = 7.32) along with their source soils (~8.3), but the in vitro plants microbiomes had a substantial reduction in diversity (Mpoly = 3.69; Mpala = 1.35). We also observed diversity reduction by means of Simpson’s diversity index that assesses the probability that two sampled individuals will belong to different OTUs. We found the Simpson’s diversity index to be high for the wild Marchantia species (D > 0.99) but lower for M. polymorpha (D = 0.903) and M. paleacea (D = 0.576) under in vitro conditions. Marchantia species lack roots, but have single elongated cells called rhizoids. The complete Marchantia individual is only a few cell layers thick. Various models of root diversity were proposed. One such model was the two-step selection of rhizosphere microbiota (Bulgarelli et al.11) where the diversity decreased from soil to rhizosphere to endosphere. However, the model failed to account for every plant. Multiple accounts in the literature reported the rhizosphere was more diverse than its surrounding soil, such as rhizospheres of black pepper38 and rice9. Global meta-analysis also showed that plant rhizosphere diversity had a larger median than its soil or sediments39. One possible explanation for this diversity was that plant exudates influenced nutrient availability.

Table 1.

Marchantia OTU richness and alpha diversity indices.

| Sequenced reads (after QC) | Raw OTUs (97% identity 16S rRNA gene) | OTUs (without singletons) | Chao1 (±SE) | Shannon (H) | Simpson (D) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild M. paleacea | 175,252 | 17,613 | 10,070 | 11420.56 ± 87.79 | 8.29 | 0.998 |

| Wild M. polymorpha | 145,321 | 9,461 | 6,188 | 7048.66 ± 74.27 | 7.32 | 0.996 |

| Soil M. paleacea | 143,690 | 15,215 | 8,367 | 9696.03 ± 92.02 | 8.27 | 0.999 |

| Soil M. polymorpha | 144,918 | 15,051 | 8,313 | 9593.76 ± 90.75 | 8.26 | 0.999 |

| in vitro M. paleacea | 197,540 | 585 | 402 | 422.00 ± 10.56 | 1.35 | 0.576 |

| in vitro M. polymorpha | 167,224 | 1,882 | 1162 | 1229.50 ± 24.55 | 3.69 | 0.903 |

Number of assembled sequences with a read median size of 460 bp. We observed a total of 36,299 OTUs. The most diverse samples were the wild Marchantia and their soils. An expected, diversity dramatically decreased for the in vitro Marchantia species. Diversity indexes were calculated without singletons.

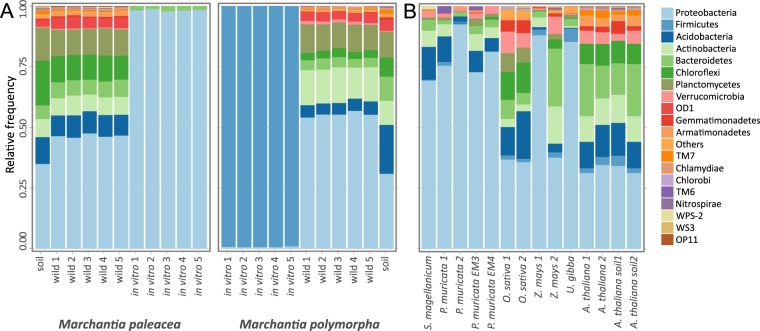

We conducted taxonomic assignments of the OTUs, showed phyla affiliations for each sample, and transformed the data sets to a relative frequency (Fig. 2). The two wild Marchantia hosted larger Proteobacteria OTUs than their source soils. The second most abundant phylum hosted by M. paleacea was Planctomycetes while M. polymorpha hosted Actinobacteria . Despite having similar abundance patterns of the main phyla, the two Marchantia species could be distinguished based on their wild and in vitro microbiome profiles. The most abundant phylum hosted by the Marchantia species was Proteobacteria for all samples, except for in vitro M. polymorpha plants that hosted more Firmicutes . In both wild Marchantia species, the amount of Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia was higher in plant microbiomes than in their soils. On the other hand, Acidobacteria, Chloroflexi, Planctomycetes, Bacteroidetes, TM7, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospirae, Verrucomicrobia, Chlorobi, and Firmicutes phyla had lower proportions in the wild plants relative to source soils (Fig. 2A). While Firmicutes was detected in all samples and better represented in the in vitro M. paleacea microbiome elsewhere for wild plants nor soils . As expected, the in vitro Marchantia species hosted lower overall diversity than their wild relatives. In the case of M. paleacea, diversity was largely dominated by Proteobacteria and small amounts of Bacteroidetes . For in vitro M. polymorpha, Firmicutes was the main phyla in addition to a small fraction of Proteobacteria (Fig. 2A). A detailed breakdown of the diversity within phyla is presented in the Supplementary Figures (Supplementary Figs S1–S5).

Figure 2.

Phyla diversity in Marchantia microbiomes and a concise comparison of plant-related microbiomes. (A) M. paleacea and M. polymorpha microbiomes. Proteobacteria was the most abundant phylum for both wild M. paleacea and M. polymorpha, but Firmicutes dominated the microbiome diversity of in vitro M. polymorpha. (B) Proteobacteria was the most abundant phylum in the plant microbiomes analyzed but each microbiome had different frequencies, spanning from 30% up to 90%. Plant microbiomes were ordered according to their phylogenetic distances. Sphagnum moss13 served a representative for bryophytes (along with Marchantia species); Pinus represented gymnosperms14; rice16 and maize15 represented monocots; and the carnivorous plant Utricularia gibba68 and Arabidopsis11 represented dicots (see Methods).

To better understand the relevance of a Marchantia microbiome composition relative to microbiomes from other non-vascular and vascular plants (Fig. 2B; Table 2), we compared Marchantia bacterial communities with microbiomes from the bryophyte moss Sphagnum magellanicum, the gymnosperm Pinus muricata (containing two datasets, one dataset from roots containing arbuscular mycorrhiza and another dataset from mycorrhizae-free roots), rice, maize, Arabidopsis thaliana, and the bladders from Utricularia gibba (see Methods). Taking into account that the gametophytic thalli of both Marchantia species grew as laminar sheets attached to the soil by rhizoids, we decided to focus our comparative analysis on microbiomes from rhizospheres of representative species. By comparing the most abundant phyla across all datasets (Fig. 2B), we observed common features for all of the plant microbiomes, such as a high relative abundance of Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes for most of the plants analyzed. Some samples showed a strong bias towards Proteobacteria (>0.50), including M. polymorpha (wild), Pinus muricata, S. magellanicum, Utricularia gibba, and a subgroup from the maize microbiome samples. Several non-cultivable bacteria phyla appeared to be widely distributed in plants microbiomes albeit in lower abundances, such as OD1, TM7, WPS-2, WS3, and OP11. Detailed OTU tables and taxonomic assignments are available as supplementary information (Supplementary Tables S1–S5).

Table 2.

Alpha diversity indices in the comparison of microbiomes.

| Shannon | Simpson | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. paleacea wild | 8.29 | 0.998 | This work |

| M. polymorpha wild | 7.32 | 0.996 | This work |

| M. paleacea iv | 1.35 | 0.576 | This work |

| M. polymorpha iv | 3.69 | 0.903 | This work |

| S. magellanicum | 8.62 | 0.999 | (Bragina et al.73) |

| Pinus muricata | 4.97 | 0.979 | (Nguyen & Bruns74) |

| P. muricata, no mycorrhiza | 5.12 | 0.985 | (Nguyen & Bruns74) |

| O. sativa | 9.68 | 0.999 | (Edwards et al.9) |

| Z. mays | 5.97 | 0.986 | (Peiffer et al.10) |

| A.thaliana | 7.19 | 0.998 | (Lundberg et al.7) |

| U. gibba | 8.49 | 0.999 | (Alcaraz, et al.75) |

| M. paleacea soil | 8.27 | 0.999 | This work |

| M. polymorpha soil | 8.26 | 0.999 | This work |

| A. thaliana soil | 7.52 | 0.999 | (Lundberg et al.7) |

M. paleacea displays more diversity than M. polymorpha in wild conditions, but the reverse is true for in vitro conditions. There is a slight decrease in diversity in P. muricata without endo-mycorrhizae. Diversity was estimated via individual study clustering. Sequences were publicly available, as stated in their publications.

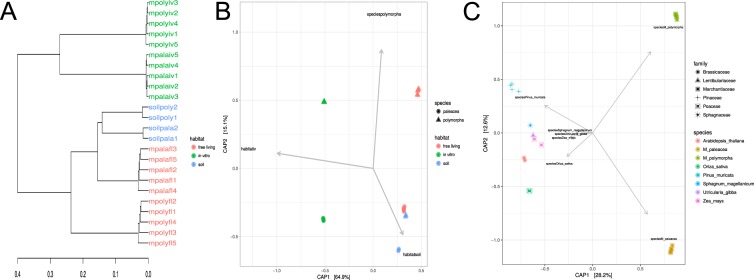

Using Shannon’s index, we sorted the microbiomes under comparison based on their diversity (Table 2). Under wild conditions, M. paleacea displayed more diversity than M. polymorpha, but this diversity was reversed under in vitro conditions. All of the microbiomes under comparison showed large dominance values (Simpson >0.9) except for in vitro M. polymorpha. This discrepancy suggested that the microbial guests of M. polymorpha were not as structured as the other plants. In addition, random colonization by opportunistic bacteria might have occurred rather than a guest-host recognition and selection process (Table 2). The lack of microbiome diversity for M. polymorpha was supported by beta diversity analyses using both weighted and unweighted Unifrac distances and visualized with constrained analysis of principal coordinates (CAP). We found significant differences (p = 1e-04) between the M. polymorpha microbiome compositions under in vitro and wild conditions (Fig. 3A). Weighted Unifrac distances showed that lower diversity of M. polymorpha translated into a larger distance from its soil source than the wild plants of M. paleacea. Meanwhile, the in vitro microbiomes featured a distant external group compared to their wild relatives. Each species group formed a single cluster that supported a selective microbiome process for each species (Fig. 3B). The comparative analyses against other microbiomes was only possible through CAP using Bray-Curtis dissimilarities. We were unable to perform Unifrac, because the 22 samples were obtained by different methods and were not alignable (see Methods). The analyses showed significant differences (p > 0.001) between plant taxonomy (family and species) such that the microbiome composition variance split Marchantia from the rest of species. These analyses accounted for 28.2% of the variation (Fig. 3C). Additional beta diversity comparisons using 43 different beta diversity distances and three other types of method comparisons are available as Supplementary Fig. S8.

Figure 3.

Comparison of plant microbiomes. (A) Weighted Unifrac distances for the Marchantia microbiomes were tested in this work. Diversity reduction in wild M. polymorpha (mpolyfl) showed a larger distance to its soil source when compared to M. paleacea (mpalafl). (B) Constrained analysis of principal coordinates (CAP) using weighted Unifrac distances with 9,999 permutational multivariate ANOVA showed significant (p > 1e-04) differences between in vitro, soil, and M. polymorpha microbial communities. (C) CAP of comparative literature plant-associated microbiomes using Bray-Curtis dissimilarities showed significant differences (p > 0.001) between microbial communities of different host plant species. Larger differences were found in Pinus, rice, and Marchantia species of this work.

Marchantia soil and in vitro microbiome interactions

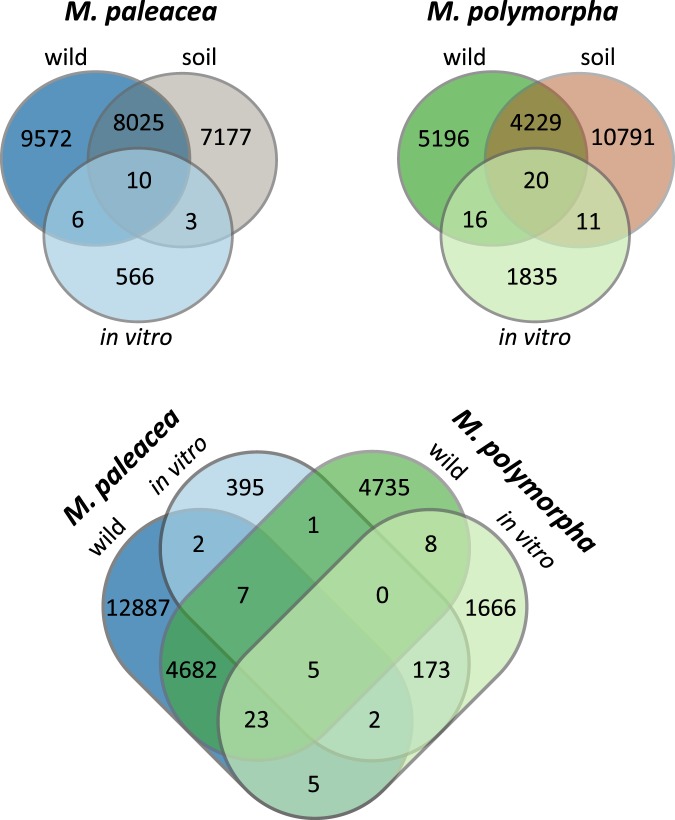

We conducted both qualitative and quantitative analyses to determine the shared, unique, and significantly different features for Marchantia species and their soils. First, the qualitative approach of comparing datasets showed that 8,035 OTUs were shared between M. paleacea and its soil, 7,180 OTUs were unique to the soil, and 9,578 OTUs were unique to the wild plant (Fig. 4). Wild M. polymorpha displayed less diversity (9,461 OTUs) than wild M. paleacea (17,613 OTUs) while both plants shared 4,717 OTUs. We found 180 OTUs in both in vitro grown plant species. We observed 16 OTUs shared between wild and in vitro M. paleacea possibly due to having similar microbial survivors of various in vitro selection constraints. A group of 569 OTUs were exclusive to in vitro plants. In future experiments, we plan to test whether this exclusive set is the result of opportunistic or host selected bacteria. M. polymorpha showed a similar case with 4,249 OTUs shared between the wild plant and soil and 5,212 exclusive OTUs in the wild plant. Only 36 OTUs were shared between wild and in vitro M. polymorpha while 1,846 OTUs were unique to the in vitro plant (Fig. 4). Relative abundances of the OTUs and their identities in a Venn diagram are available as Supplementary Table S6. We were surprised by the large number of particular plant OTUs. Some of these unique bacteria could come directly from air and water. However, air and water microbiomes were found to be less diverse than soil microbial communities. Rainwater and river microbial diversity (Chao1 index) was under 1,000 OTUs, while diversity from air was below 600 OTUs40,41. The results were congruent with the rarefaction analysis (Supplementary Fig. S7). This diversity of microbial sources suggested that plant microbiome composition was influenced by plant-environmental interactions with some bacteria transferred from plant to plant and others dispersed by soil, air, or water.

Figure 4.

Venn diagrams of microbiomes from M. paleacea, M. polymorpha and their soils. Above, OTUs are compared from in vitro, wild and soil microbiomes of each Marchantia species. Below, wild and soil microbiomes are compared from the two Marchantia species.

On the other hand, the union set between the two Marchantia species and their soils constituted only five OTUs. The identity of these five OTUs which we called Marchantia microbiome members were assigned up to the genus level as Methylobacterium (Alphaproteobacteria; (relative reads abundance) ra = 0.00066), Rhizobium (Alphaproteobacteria; ra = 0.0029), Paenibacillus chondroitinus (Firmicutes; ra = 0.0222), Citrobacter (Gammaproteobacteria; ra = 0.00013) and Methylobacterium organophilum (ra = 0.00036). The relevance of the five taxa relied on a core community assumption. The core microbial community came from the soil, and the shared microbiomes was modulated by the plant hosts. This qualitative approach allowed us to determine which microbes had an intimate relation with their hosts. Next, we summarized information about the abovementioned taxa showing that their genera featured plant-associated lifestyles.

Paenibacillus chondroitinus (Firmicutes; ra = 0.0222), previously classified as Bacillus chondroitinus, was named for its ability to degrade complex carbohydrates, such as chondroitin and alginates (Nakamura, 1987). It was discovered to be a core member of the Marchantia microbiome (<0.95 confidence, as a species). Chondroitin and alginates play a role in diverse desiccation tolerance mechanisms in bacteria. For example, common soil bacteria, such as Azotobacter vinelandii, have the ability to produce alginates that are crucial for the development of desiccation resistant cysts. Bacteria produced alginates can also be used as virulence factors, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa which happens to infect plants, insects, nematodes, and mammals42,43. Desiccation was one of the major challenges for plants during the transition from an aquatic to a terrestrial environment. M. polymorpha has been used as a model to study desiccation tolerance44,45. In the case of Marchantia accompanying bacteria, desiccation resistance strategies—like the one used by Azotobacter (alginate mediated) or the formation of spores like those in Bacillus—highlight the importance of molecular mechanisms for drought resistance in plants and their microbes. At the end of the dry season, drought resistance related compounds should be metabolized as is the case of chondroitin being degraded by P. chondroitinus. Additionally, alginate and depolymerized alginates have been shown to promote plant root growth by the induction of auxin biosynthesis genes in the plant46,47.

Methylobacterium species are plant-associated bacteria in both phyllosphere and roots, forming nodules in some species, helping with nitrogen fixation, and producing cytokinin trans-zeatin. They are known as pink-fermented facultative methylotrophic bacteria (PPFM) and are able to grow on single carbon sources (methanol and methylamine) as well as other C2, C3, and C4 sources48–50. The residence of Methylobacterium OTUs within Marchantia species was supported in other research where the same Methylobacterium species were present in year-long transgenerational experiments involving Arabidopsis49. Methylobacterium was found to occur as a core microbiome component for the dwarf shrub Andromeda polifolia found in alpine bog vegetation that was dominated by Sphagnum species51. Additionally, the pink pigmented bacterial colonies of Curtobacterium and a Rhizobiaceae were observed in our in vitro grown M. polymorpha and M. paleacea. A new Methylobacterium species, M. marchantiae species nov., was isolated from a thallus of M. polymorpha31. Methylobacterium is a phytosymbiont for liverworts and mosses. Some believe methanol is consumed in liverworts as the by-product of the plant’s cell wall metabolism and then emitted through Marchantia’s upper epidermis stomata-like pores31,52. Methylobacterium probably accumulates within the plant’s air chambers. Methylotenera is another member of methylotrophic bacteria (C1 as source) prevalent in M. paleacea. Methylotenera mobilis grew in the presence of methylamine as a source of carbon, nitrogen, and energy under laboratory conditions, but methylotrophy seemed to be facultative under natural conditions53. Our study confirmed the presence of two Methylobacterium OTUs (147,611 and 150,024 OTU ID) that were present in wild and in vitro M. paleacea and M. polymorpha plants as well as soil. Marchantia stomata-like pores (air chambers), visible to the naked eye, remained open most of the time as they were not finely regulated. Air chambers allowed gas exchange to occur while controlling the contact of internal moisture with photosynthetic cells54. Methanol was emitted as a volatile organic compound (VOC) from leaves and through plant stomata55, and the release of plant methanol was correlated with leaf growth52. The air chambers of Marchantia proved to be an ideal habitat for various bacteria, possibly Methylobacterium, that made use of C1 sources, such as methanol.

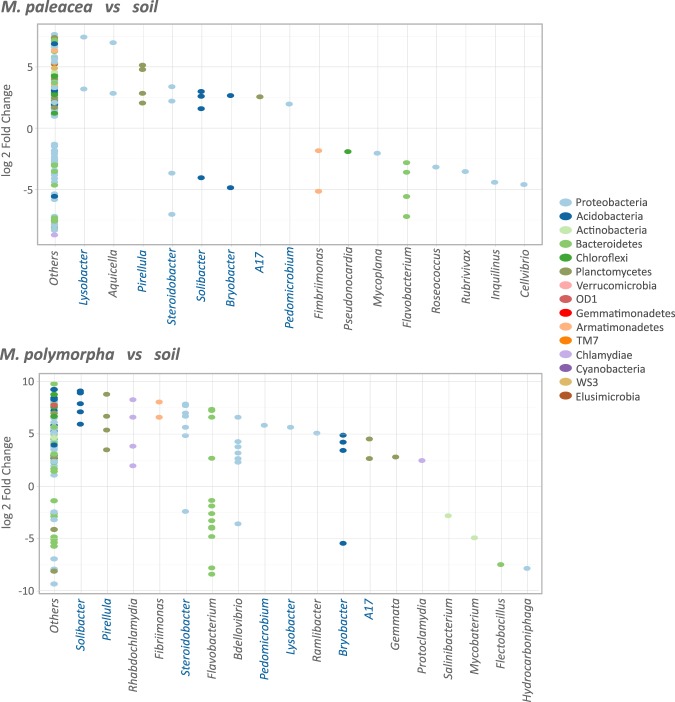

We used a quantitative approach to detect interactions between significantly different OTUs among plants and soil bacteria by comparing the log2 fold change (log2fc) of the OTU abundance ratio for wild Marchantia species versus their soil (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table 6). We used DESeq256 log2fc where fold changes less than one were negative values and fold changes greater than one were positive values, making it easy to plot the changes symmetrically in a single plot. Then we obtained an adjusted p-value (padj > 0.01) to correct for false positives (False Discovery Rate, FDR) using the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction57. A total of 201 OTUs of M. paleacea and 280 OTUs of M. polymorpha displayed a significant (padj < = 0.01) change of abundances compared their soils (Fig. 5). The majority of OTUs were Proteobacteria from both M. paleacea (44%) and M. polymorpha (35%), followed by Bacteroidetes, Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria and Planctomycetes that contained around 9% (for each phylum) of the significant OTUs from both plants. The “Others” category in Fig. 5 corresponded to the vast majority of OTUs that were not phylotyped up to genus level (171/201 M. paleacea; 222/280 M. polymorpha) but to at least the phylum level and pertained to bacteria with significant log fold changes due to their source. Seven highly represented phylotyped genera along with both wild Marchantia species could play a major role in plant growth and development, including Lysobacter, Pirellula, Steroidobacter, Solibacter, Bryobacter, A17, and Pedomicrobium. Several OTUs were in surprisingly lower numbers in the plants which indicated a negative interaction. Some genera, such as Flavobacterium or Steroidobacter, showed OTU-specific enrichments and depletions that suggested species or strain specific relationships between plant and bacteria.

Figure 5.

Relative abundance of the bacteria associated with Marchantia. The genera with significant (padj = 0.01) log2 fold changes are shown. “Other” corresponds to OTUs whose genera could not be assigned. Each dot represents an OTU. The OTUs prevalent in the Marchantia species are located on top of the plot while the OTUs prevalent in soil are located at the bottom. The majority of the OTUs were not assigned to a known genus, and are shown as “Others” in the plots. Shared genera between both Marchantia species are highlighted in blue.

Plants contained derived photosynthates as carbon sources, thus their associated microbes were expected to feature metabolic machinery that were able to utilize such sources. These specialized carbon consumers, such as Bryobacter (Acidobacteria), were prevalent in wild Marchantia. These bacteria have been described as a typical component of Sphagnum-dominated bogs. They are non-motile and grow well on the residual products of Sphagnum decay, such as complex heteropolysaccharides, glucuronic acids, and galacturonic acids58. Another bacterial genus dominating M. paleacea includes Steroidobacter (γ-Proteobacteria) which was isolated from soils and plant roots59,60. Some strains, such as Steroidobacter agariperforans, degrade complex polysaccharides derived from rhizospheres and can even degrade agar. S. agariperforans was isolated as a commensal strain to a Rhizobiales bacterium59. S. denitrificans was discovered to denitrify under anoxic conditions using nitrate as an electron acceptor and to degrade steroidal hormones60. Denitrification could be parallel to nitrogen fixation. Denitrification in roots and nodules could reduce cytotoxic damages produced by nitrates. These nitrates could inhibit nitrogen fixation and be a final electron acceptor for rhizobia when the plant is under environmental stress, such as floods61. Recently, Steroidobacter was reported to be part of the core rhizosphere microbiome of the gymnosperm Welwitschia mirabilis, a 110 million-year-old living fossil62.

Predators, such as bacteria, have also been found to be attracted to a nutrient rich environment containing plant derived photosynthates. Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, the most studied species of the Bdellovibrio genus, is a sophisticated Gram-negative bacterial predator63. Bdellovibrio species were isolated from a wide range of environments, including plant rhizospheres. The concentration of B. bacteriovorus in rhizospheres can reach levels higher than one order of magnitude relative to the circumventing soil. Bdellovibrio likely preys on bacteria attracted to the C-rich plant exudates64. The noticeably high concentration of Bdellovibrio on Marchantia is interesting, because it might prey on other Gram-negative inhabitants that are potential pathogens, such as Agrobacterium. Agrobacterium was reported to be prevalent in M. polymorpha.

A suggested explanation for the greater bacterial diversity observed in wild M. paleacea compared to M. polymorpha was consistent with previous work in which the mycorrhiza formation capabilities with glomeromycotan fungi (GA) were analyzed for a set of species of liverworts and were depleted in M. polymorpha29. Ligrone and collaborators (2007) found evidence which suggested an ancient symbiotic origin for GA and liverworts as well as several independent losses for the mycorrhiza formation across time. Molecular explanations of GA absences in M. polymorpha could be due to mutations or gene silencing in the M. polymorpha mycorrhiza plant symbiotic genes DMI1, DMI3 and IPD365. We observed a larger diversity—diversity indices and OTU richness—in the M. paleacea wild microbiome than its soil substrate. This diversity had nearly twice as many observed OTUs as M. polymorpha. The lowest microbe diversity of M. polymorpha could be due to their low symbiotic capabilities for this plant under wild conditions. Another possibility for lower microbiome diversity is consequence of both Marchantia species ecological strategies, where M. polymorpha is a primary colonizer of disturbed habitats, whereas M. paleacea is resilient in its environment26.

Potential reasons for the different microbial diversity observed in the in vitro growing plants include: 1) Microbiological condition were cleaner for M. paleacea; 2) The microbiome of M. polymorpha was composed of opportunistic and maybe transient bacteria, while M. paleacea was actively recruiting its microbial inhabitants; 3) M. paleacea actively selected and recruited microbes which might be a trait that M. polymorpha lost; and 4) Different developmental times between M. paleacea and M. polymorpha. Indeed, M. paleacea took about 28 days longer to develop gemmae cups and gemmae than M. polymorpha under our laboratory conditions. We would like to investigate these possibilities in future research. We think that in vitro conditions were providing the right selective conditions for recruiting plant-associated microbiota through a frequency dependent selection mechanism driven by the plants. Isolated bacteria from in vitro Marchantia species were reported30,31, even though the plant culture media were not optimal for bacteria growth. All carbon sources for heterotrophic bacteria should be derived from plant exudates. Some of the in vitro bacteria were probably acquired by handling in the laboratory, aerosols, dust, and several contamination sources but some of the identified microbes are closer to plant-associated bacteria that are being transferred in growth conditions.

Conclusions

For both Marchantia species, we were able to identify highly abundant OTUs from their wild sources. We observed that OTUs enriched in Marchantia showed evidence of plant-associated lifestyles supported by related cultured strains previously discussed. We identified genera of plant growth promoting bacteria (i.e. Rhizobium and Methylobacterium) and complex organic compound degrading bacteria (i.e. Paenibacillus, Steroidobacter, and Lysobacter) both reported to use plant-derived polymers and return plant hormones that provided pathogen protection to their hosts. We recorded the presence of bacterial predators, such as Bdellovibrio, that actively attacked and parasitized other Proteobacteria, suggesting that negative interactions occurred among Marchantia species inhabitants. The enrichment for methylotrophic bacteria was likely due to bacterial niche opportunity and specialization found in the Marchantia air chambers. The microbial toolkit of M. paleacea and M. polymorpha could facilitate understanding whether the microbial input affects plant development.

Methods

Sampling

A total of 30 Marchantia polymorpha and 30 M. paleacea specimens were collected in wild conditions near the locality of Oxtlapa, a municipality of Xico in the Mexican state of Veracruz (19°25′26″N, 97°3′31″W and 19°25′33″N, 97°3′31″W elev. 1,763 masl; collection date: 7/3/2013). Both plant species were growing in a rocky substrate with shallow soil (<1 cm). This location was chosen because both species were naturally occurring in sympatric conditions with less than 200 m between sampling sites for each species (see Supplementary Fig. S6). We collected specimens in the field with sterilized tweezers and carefully removed adhering soil particles. The cleaned specimens were placed into 50 ml sterile tubes that were frozen in place with liquid nitrogen. We collected approximately 50 ml of soil volume from each plant location to study its role as an inoculant for the Marchantia microbiomes. Landowners allowed us to sample within their terrain without the need of a special collection permit. Neither Marchantia species were found on the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; http://www.iucnredlist.org/search). Gemmae from both Marchantia (female) species grown in the wild were disinfected and grown under in vitro conditions (following the detailed protocols described in Ishizaki et al. 2016) to generate thalli. We recovered gemmae from in vitro cultured thalli, and the resulting gemmae were grown and propagated in vitro for three subsequent cycles (gemmae-to-gemma). We processed the resulting thalli for DNA isolation.

DNA extraction and sequencing library preparation

Five plant specimens of each Marchantia species were used for each treatment (wild and in vitro) for DNA extractions. The naturally occurring populations of M. polymorpha and M. paleacea were gently washed away from the surrounding particles with phosphate buffer. Then they were washed by vortex mixing with 1% Tween-20 and the resulting pellets were used to extract the metagenomic DNA. We used the same procedure on the in vitro specimens of the Marchantia species. These samples were removed from the agar plate with sterile tweezers and washed with 1% Tween-20 since there were no soil particles attached to them. We washed the plant pellets and soil samples to extract plant-derived metagenomic DNA following MoBio’s PowerSoil procedures (MoBio Laboratories, Solana Beach, CA). We observed the Marchantia microbiome as the microbes attached to plant thalli surfaces. Because of the small size of the plants (1 cm × 5 cm; and only a few cell layers thick), we recovered microbes from the rhizoids, epidermis, pores that were analogous to the rhizosphere, phylosphere, and endophytic microbiome of other plants We followed the phosphate buffer washing-vortexing protocol that was used in several plants microbiome studies7.

We used PCR primers from the V3-V4 (341 F, 805 R; 464 bp amplicon) region of the 16S rRNA gene (Klinsworth 2012) which was recommended by the MiSeq™ Illumina® protocol with 5′ overhangs for multiplex library preparation. We performed triplicate PCR reactions using a final volume of 30 μL using high fidelity Pfx platinum polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and mixed all the reactions per sample to a final volume of 90 μL. The PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min; 5 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, and extension at 68 °C for 30 s; 25 cycles of two-step cycling with denaturation at 94 °C for 5 s, and extension at 68 °C for 30 s. PCR products were column purified using High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The 16S rRNA amplicon libraries were constructed (barcodes and Illumina multiplex sequencing adapters added) and sequenced at the Unidad de Secuenciación Masiva at the National Autonomous University of Mexico’s Biotechnology Institute, using a Illumina® MiSeq™ run with a 2 × 300 bp configuration based on manufacturer’s directions.

Sequence processing

We used a previously reported pipeline for 16S amplicon sequences66 (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3470555.v1). Briefly, we merged paired-end reads using PANDASEQ (Masella, Bartram, Truszkowski, Brown & Neufeld 2012) and used FASTX tools for quality control (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/). We trimmed all of the reads to the expected amplicon size (250 bp) and assembled them using the following parameters: a minimum probability threshold of 0.95 that accounts for the minimum probability cut-off for assembly; a minimum length of 250 bp, and a maximum length of 470 bp. Clustering and OTU picking was done using CD-HIT-EST with a 97% identity cutoff and a minimum of 97% for the read length. We tested multiple open and closed-reference OTU picking strategies and decided to use the CD-HIT program, because it fit our computer cluster configuration and the OTU range was enormous—from 6,806 to 896,439 OTUs—depending on the chosen software (QIIME options). We built the OTU table using make_otu_table.py of QIIME’s suite67 and picked the representative OTUs. We conducted taxonomy assignment with BLAST against the Greengenes database (13_8 release68). We identified chimeras and removed them with ChimeraSlayer69. Finally, we identified and removed mitochondrial and chloroplast sequences from the following analyses.

Diversity metrics and statistical analysis

All of the diversity metrics were calculated with R (R Core Team 2014) and its phyloseq70, and vegan71 packages. We created plots using R′s phyloseq, ggplot2 (Wickham 2009) and RColorBrewer (www.ColorBrewer.org) libraries. With the alpha diversity metrics, we calculated the number of observed species, nonparametric Chao1 index35–37, Shannon’s index72, and Simpson’s diversity index (Simpson) for the Marchantia species and the comparative dataset. We generated Venn diagrams using the Draw Venn Diagram tool (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/). We calculated community distances with phyloseq. Several normalization procedures were conducted on the data, including performing relative frequency transformation to obtain bar plots that compared phyla abundances across samples/species. To search for significant differences between Marchantia samples, we applied a normalized logarithmic transformation (rlog) on the OTUs. We computed counts by fitting each OTU to an abundance baseline using a generalized linear model (GLM) and estimated logarithmic fold change (LFC) and dispersion for each OTU. We corrected for false positives (False Discovery Rate, FDR) using the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) correction. We made these comparisons using the R′s DESeq2 package56. Detailed R procedures can be found in Supplementary Table S7.

Compared microbiomes

For comparison purposes, we chose several available root microbiomes for plant species in order to get a general representation of land plants. From publicly available repositories of published data (see Table 2), we selected sequences from one Sphagnum magellanicum moss microbiome73 and four samples from a Pinus muricata rhizosphere microbiome study74. We selected root microbiome samples from individuals with and without arbuscular mycorrhizas, two samples from B73 maize root microbiomes10, two samples from rice’s roots (Edwards et al.9), one sample from bladder associated microbes of the carnivorous plant Utricularia gibba75; and two root associated microbiomes from Arabidopsis thaliana7. Sequences for comparative microbiomes were downloaded from the databases stated in their respective publications. All of the sequences groups were processed individually (see Sequence processing) for diversity estimations. We performed QIIME’s pick_closed_otus.py (Caporaso et al.67) using a similarity cutoff of 0.97 and utilized the gg_otus_13_8 database68. Although the comparison microbiome studies were conducted with different technologies, sequencing lengths, and 16S rRNA gene variable regions, we were able to compare the samples using a closed-reference full-length 16S rRNA sequence to cluster the sequences.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Jesús Dorantes-López, Elisa Acosta-Avilés, Liliana Arteaga-Dorantes and Elena Arteaga-Dorantes (Landowners) for permission to collect soil and plant samples. We thank Hugo R. Barajas de la Torre for sampling support. We also thank Takayuki Kohchi and Kimitsune Ishizaki for sharing unpublished protocols for in vitro culturing of Marchantia. This research was funded by UCMEXUS Collaborative program (grant 2011-UCMEXUS-19941-44-OAC7), Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología - Ciencia Básica (CONACYT - Basic Research) (grants CB-158550 and CB-158561), COSEAMX1 JEAI EPIMAIZE grant from the Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Royal Society Newton Advance Fellowship (NA150181) project number RG79985, Universidad Veracruzana (Cuerpo Académico CA-UVER-234), DGAPA-PAPIIT-UNAM (grants IA200514 and TA200117) and CONACYT Ciencia Básica CB-237387. We are thankful for the suggestions of two anonymous reviewers which together improved our manuscript. We thank Carolyn Smith of Peace Corps Response for editing the manuscript.

Author Contributions

L.D.A., M.P., A.E.D.A. and M.A.A.V. conceived the project, analyzed the data and provided reagents. L.D.A., M.P., A.E.D.A., J.L.B. and M.A.A.V. wrote the paper. L.D.A., H.R.B., and M.A.A.V. collected the wild soil and plants. A.E.D.A. established and perpetuated the plant material under in vitro conditions. M.P. performed metagenomic DNA extraction and library preparations for sequencing. L.D.A. and M.P. created the figures.

Data availability

Data for the Marchantia microbiome was deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ Bioproject database under the accession code PRJNA320287. Raw genomic sequence data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ for the whole study under the accession code SRP078003 as well as the following individual accessions: SRR3746049, SRR3746050, SRR3746051, SRR3746052, SRR3746053 and SRR3746054. Raw OTU tables, taxonomic assignments for Marchantia and the comparative dataset are available as supplementary information (Supplementary Tables S1–S5).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Luis D. Alcaraz, Email: lalcaraz@ciencias.unam.mx

Mario A. Arteaga-Vázquez, Email: maarteaga@uv.mx

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-31168-0.

References

- 1.Turner, T. R. et al. Comparative metatranscriptomics reveals kingdom level changes in the rhizosphere microbiome of plants. ISME J. 1–11, 10.1038/ismej.2013.119 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Carella P, Schornack S. Manipulation of Bryophyte Hosts by Pathogenic and Symbiotic Microbes. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;59:651–660. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcx182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vandenkoornhuyse P, Quaiser A, Duhamel M, Le Van A, Dufresne A. The importance of the microbiome of the plant holobiont. New Phytol. 2015;206:1196–1206. doi: 10.1111/nph.13312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strullu-Derrien, C., Selosse, M. A., Kenrick, P. & Martin, F. M. The origin and evolution of mycorrhizal symbioses: From palaeomycology to phylogenomics. New Phytologist, 10.1111/nph.15076 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Knack JJ, et al. Microbiomes of Streptophyte Algae and Bryophytes Suggest That a Functional Suite of Microbiota Fostered Plant Colonization of Land. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2015;176:405–420. doi: 10.1086/681161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field KJ, et al. Contrasting arbuscular mycorrhizal responses of vascular and non-vascular plants to a simulated Palaeozoic CO2 decline. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:835. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundberg DS, et al. Defining the core Arabidopsis thaliana root microbiome. Nature. 2012;488:86–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulgarelli D, et al. Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature. 2012;488:91–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edwards J, et al. Structure, variation, and assembly of the root-associated microbiomes of rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E911–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414592112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peiffer JA, et al. Diversity and heritability of the maize rhizosphere microbiome under field conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:6548–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302837110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulgarelli D, Schlaeppi K, Spaepen S, van Themaat EVL, Schulze-Lefert P. Structure and Functions of the Bacterial Microbiota of Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013;64:807–838. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rayner MC. Mycorrhiza. New Phytol. 1927;26:22–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1927.tb06704.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stahl M. Die Mykorrhiza der Lebermoose mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der thallösen Formen. Planta. 1949;37:103–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01929705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson JM, Hauser DA, Hinson R, Shaw AJ. A novel experimental system using the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha and its fungal endophytes reveals diverse and context-dependent effects. New Phytol. 2018;217:1217–1232. doi: 10.1111/nph.15012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bond G, Scott GD. An Examination of some Symbiotic Systems for Fixation of Nitrogen. Ann. Bot. 1955;14:67–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a083419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodgers GA, Stewart WDP. The Cyanophyte-Hepatic Symbiosis. I. Morphology and Physiology. New Phytol. 1977;78:441–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1977.tb04851.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams DG, Duggan PS. Cyanobacteria-bryophyte symbioses. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59:1047–1058. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koua FHM, Kimbara K, Tani A. Bacterial-biota dynamics of eight bryophyte species from different ecosystems. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2015;22:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2014.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang, J. Y., Ma, J., Li, X. D. & Li, Y. H. Illumina sequencing-based community analysis of bacteria associated with different bryophytes collected from Tibet, China. BMC Microbiol. 16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Wang, S., Tang, J. Y., Ma, J., Li, X. D. & Li, Y. H. Moss habitats distinctly affect their associated bacterial community structures as revealed by the high-throughput sequencing method. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 34 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Marks, R. A., Smith, J. J., Cronk, Q. & McLetchie, D. N. Variation in the bacteriome of the tropical liverwort, Marchantia inflexa, between the sexes and across habitats. Symbiosis 1–9, 10.1007/s13199-017-0522-3 (2017).

- 22.Oostendorp, C. The bryophytes of the Palaeozoic and the Mesozoic. (J. Cramer, 1987).

- 23.Schofield, W. B. Introduction to bryology. (Blackburn Press, 2001).

- 24.Bowman JL. A brief history of marchantia from Greece to genomics. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57:210–229. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger F, Bowman JL, Kohchi T. Marchantia. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:R186–R187. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowman JL, et al. Insights into Land Plant Evolution Garnered from the Marchantia polymorpha Genome. Cell. 2017;171:287–304.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golenkin M. Die Mycorrhiza-ahnlichen Bildungen der Marchantiaceen. Flora. 1902;90:209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell J, Bulman S. The liverwort Marchantia foliacea forms a specialized symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the genus Glomus. New Phytol. 2005;165:567–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ligrone R, et al. Glomeromycotean associations in liverworts: A molecular, cellular, and taxonomic analysis. Am. J. Bot. 2007;94:1756–1777. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.11.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kutschera U, Koopmann V. Growth in liverworts of the Marchantiales is promoted by epiphytic methylobacteria. Naturwissenschaften. 2005;92:347–349. doi: 10.1007/s00114-005-0640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schauer S, Kämpfer P, Wellner S, Spröer C, Kutschera U. Methylobacterium marchantiae sp. nov., a pinkpigmented, facultatively methylotrophic bacterium isolated from the thallus of a liverwort. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011;61:870–876. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.021915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mewari N, Kumar P. Antimicrobial Activity of Extracts of Marchantia polymorpha. Pharm. Biol. 2008;46:819–822. doi: 10.1080/13880200802315725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishizaki K, Johzuka-Hisatomi Y, Ishida S, Iida S, Kohchi T. Homologous recombination-mediated gene targeting in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha L. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1532. doi: 10.1038/srep01532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuster, R. M. The Hepaticae and Anthocerotae of North America east of the hundredth meridian. (Columbia University Press, 1992).

- 35.Gotelli, N. J. & Chao, A. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity5, 195–211 (Elsevier Ltd., 2013).

- 36.Gotelli NJ, Colwell RK. Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol. Lett. 2001;4:379–391. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00230.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes JB, Hellmann JJ, Ricketts TH, Bohannan BJM. Counting the uncountable: statistical approaches to estimating microbial diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:4399–406. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4399-4406.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z, et al. Different responses of rhizosphere and non-rhizosphere soil microbial communities to consecutive Piper nigrum L. monoculture. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35825. doi: 10.1038/srep35825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson, L. R. et al. A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature, 10.1038/nature24621 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Chidamba L, Korsten L. Pyrosequencing analysis of roof-harvested rainwater and river water used for domestic purposes in Luthengele village in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015;187:41. doi: 10.1007/s10661-014-4237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lymperopoulou DS, Adams RI, Lindow SE. Contribution of Vegetation to the Microbial Composition of Nearby Outdoor Air. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:3822–33. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00610-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hay ID, Rehman ZU, Moradali MF, Wang Y, Rehm BHA. Microbial alginate production, modification and its applications. Microb. Biotechnol. 2013;6:637–650. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yorgey P, Rahme LG, Tan M-W, Ausubel FM. The roles of mucD and alginate in the virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in plants, nematodes and mice. Mol. Microbiol. 2008;41:1063–1076. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatanaka R, Sugawara Y. Development of desiccation tolerance and vitrification by preculture treatment in suspension-cultured cells of the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. Planta. 2010;231:965–976. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akter K, Kato M, Sato Y, Kaneko Y, Takezawa D. Abscisic acid-induced rearrangement of intracellular structures associated with freezing and desiccation stress tolerance in the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha. J. Plant Physiol. 2014;171:1334–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hien NQ, et al. Growth-promotion of plants with depolymerized alginates by irradiation. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2000;59:97–101. doi: 10.1016/S0969-806X(99)00522-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, et al. The promoting effects of alginate oligosaccharides on root development in Oryza sativa L. mediated by auxin signaling. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014;113:446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jourand P, et al. Methylobacterium nodulans sp. nov., for a group of aerobic, facultatively methylotrophic, legume root-nodule-forming and nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004;54:2269–2273. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knief C, Ramette A, Frances L, Alonso-Blanco C, Vorholt JA. Site and plant species are important determinants of the Methylobacterium community composition in the plant phyllosphere. ISME J. 2010;4:719–728. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lidstrom ME, Chistoserdova L. Plants in the pink: Cytokinin production by Methylobacterium. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:1818. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.7.1818.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bragina A, Berg C, Berg G. The core microbiome bonds the Alpine bog vegetation to a transkingdom metacommunity. Mol. Ecol. 2015;24:4795–4807. doi: 10.1111/mec.13342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hüve K, et al. Simultaneous growth and emission measurements demonstrate an interactive control of methanol release by leaf expansion and stomata. J. Exp. Bot. 2007;58:1783–1793. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalyuzhnaya MG, et al. Functioning in situ: gene expression in Methylotenera mobilis in its native environment as assessed through transcriptomics. ISME J. 2010;4:388–98. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glime, J. M. In Bryophyte Ecology (ed. Glime, J. M.) 1, 1–46 (Michigan Technological University, 2015).

- 55.Nemecek-Marshall M, Macdonald RC, Franzen JJ, Wojciechowski C, Fall R. Methanol Emission from Leaves. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:1359–1368. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.4.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kulichevskaya IS, Suzina NE, Liesack W, Dedysh SN. Bryobacter aggregatus gen. nov., sp. nov., a peat-inhabiting, aerobic chemo-organotroph from subdivision 3 of the acidobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010;60:301–306. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.013250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sakai M, Hosoda A, Ogura K, Ikenaga M. The growth of Steroidobacter agariperforans sp. nov., a novel agar-degrading bacterium isolated from soil, is enhanced by the diffusible metabolites produced by bacteria belonging to Rhizobiales. Microbes Environ. 2014;29:89–95. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME13169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fahrbach M, et al. Steroidobacter denitrificans gen. nov., sp. nov., a steroidal hormone-degrading gammaproteobacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2008;58:2215–2223. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bedmar, E. et al. In Beneficial Plant-microbial Interactions 165–182, 10.1201/b15251-9 (2013).

- 62.Valverde A, et al. Specific Microbial Communities Associate with the Rhizosphere of Welwitschia mirabilis, a Living Fossil. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0153353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rendulic S, et al. A predator unmasked: life cycle of Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus from a genomic perspective. Science. 2004;303:689–692. doi: 10.1126/science.1093027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jurkevitch E, Minz D, Ramati B, Barel G. Prey Range Characterization, Ribotyping,and Diversity of Soil and Rhizosphere Bdellovibrio spp.Isolated on Phytopathogenic Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:2365–2371. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.6.2365-2371.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang B, et al. Presence of three mycorrhizal genes in the common ancestor of land plants suggests a key role of mycorrhizas in the colonization of land by plants. New Phytol. 2010;186:514–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alcaraz LD, Hernández AM, Peimbert M. Exploring the cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus) fecal microbiome, bacterial inhabitants of a worldwide pet. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2837. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Caporaso JG, et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012;6:1621–1624. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.DeSantis TZ, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:5069–72. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Haas BJ, et al. Chimeric 16S rRNA sequence formation and detection in Sanger and 454-pyrosequenced PCR amplicons. Genome Res. 2011;21:494–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.112730.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dixon P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 2003;14:927–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2003.tb02228.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gliessman, S. R. Agroecology: Ecological Processes in Sustainable Agriculture. Agroecol. Ecol. Process. Sustain. Agric. 28, xxiii + 357 pp.-xxiii + 357 pp. (1998).

- 73.Bragina A, et al. The Sphagnum microbiome supports bog ecosystem functioning under extreme conditions. Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:4498–4510. doi: 10.1111/mec.12885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nguyen, N. H. & Bruns, T. D. The Microbiome of Pinus muricata Ectomycorrhizae: Community Assemblages, Fungal Species Effects, and Burkholderia as Important Bacteria in Multipartnered Symbioses. Microb. Ecol. 914–921, 10.1007/s00248-015-0574-y (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Alcaraz LD, Martínez-Sánchez S, Torres I, Ibarra-Laclette E, Herrera-Estrella L. The Metagenome of Utricularia gibba’s Traps: Into the Microbial Input to a Carnivorous Plant. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for the Marchantia microbiome was deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ Bioproject database under the accession code PRJNA320287. Raw genomic sequence data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ for the whole study under the accession code SRP078003 as well as the following individual accessions: SRR3746049, SRR3746050, SRR3746051, SRR3746052, SRR3746053 and SRR3746054. Raw OTU tables, taxonomic assignments for Marchantia and the comparative dataset are available as supplementary information (Supplementary Tables S1–S5).