Abstract

Arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgRS) recognizes two major identity elements of tRNAArg: A20, located at the outside corner of the L-shaped tRNA, and C35, the second letter of the anticodon. Only a few exceptional organisms, such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, lack A20 in tRNAArg. In the present study, we solved the crystal structure of a typical A20-recognizing ArgRS from Thermus thermophilus at 2.3 Å resolution. The structure of the T. thermophilus ArgRS was found to be similar to that of the previously reported S. cerevisiae ArgRS, except for short insertions and a concomitant conformational change in the N-terminal domain. The structure of the yeast ArgRS⋅tRNAArg complex suggested that two residues in the unique N-terminal domain, Tyr77 and Asn79, which are phylogenetically invariant in the ArgRSs from all organisms with A20 in tRNAArgs, are involved in A20 recognition. However, in a docking model constructed based on the yeast ArgRS⋅tRNAArg and T. thermophilus ArgRS structures, Tyr77 and Asn79 are not close enough to make direct contact with A20, because of the conformational change in the N-terminal domain. Nevertheless, the replacement of Tyr77 or Asn79 by Ala severely reduced the arginylation efficiency. Therefore, some conformational change around A20 is necessary for the recognition. Surprisingly, the N79D mutant equally recognized A20 and G20, with only a slight reduction in the arginylation efficiency as compared with the wild-type enzyme. Other mutants of Asn79 also exhibited broader specificity for the nucleotide at position 20 of tRNAArg. We propose a model of A20 recognition by the ArgRS that is consistent with the present results of the mutational analyses.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) catalyze the esterification of their cognate tRNAs with specific amino acids. Strict recognition of both the amino acid and the tRNA by the aaRS ensures the correct translation of the genetic code. To discriminate the cognate tRNA from the non-cognate tRNAs, the aaRS recognizes characteristic features of the cognate tRNA, which are usually a small number of nucleotides, called identity elements, that comprise the identity sets (1). In most tRNAs, the identity elements are concentrated in the anticodon and/or the acceptor stem (1). This recognition mode can be explained by the fact that most synthetases interact with the inner side of the L-shaped tRNA, so that they can easily access the two extremities of the tRNA (2–7). However, in the cases of arginine, leucine, and serine, where six codons are assigned to a single amino acid in the genetic code, the anticodons of the cognate tRNAs share only one or no nucleotide. Consequently, an additional major identity element may be required in a region other than the anticodon. The leucine and serine tRNAs possess characteristically long variable arms, which are used as important identity elements in most organisms (8–13). In contrast, tRNAArg utilizes an adenosine at position 20 for the non-anticodon major identity element, which is completely conserved among the tRNAArg species in most organisms, and is missing in other tRNA species (14, 15). Actually, genetic and biochemical studies of Escherichia coli tRNAArg demonstrated that A20 is one of the major identity elements of tRNAArg, with a very high discrimination rate of three orders of magnitude on average (14, 16–19). A20 is located in a small, single-stranded region in the D loop at the outside corner of the L-shaped tRNA structure, which is far from both the anticodon and the acceptor stem. No other tRNAs specific to the other amino acids have a major identity element with such a high discrimination rate in this position.

On the other hand, the exceptional organisms that lack A20 in their tRNAArg sequences are Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and Neurospora crassa, in addition to most of the mitochondria of animals and single cell eukaryotes (15). In S. cerevisiae, the tRNAArg species have U, dihydrouridine (D), or C at position 20 (15), and the replacement of C20 by A in a tRNAArg species caused no reduction in the arginine-accepting activity (18). The crystal structure of the S. cerevisiae arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgRS) was reported at 2.85 Å resolution (20), and recently that of the complex between the S. cerevisiae ArgRS and tRNAArg was reported at 2.2 Å resolution (21). In the complex structure, the D20 of the tRNAArg is recognized by Asn106, Phe109, and Gln111 in the N-terminal domain characterizing ArgRS (21). Thus, Cavarelli and colleagues proposed a model for the canonical recognition of A20 by Phe/Tyr and Asn of other ArgRSs, corresponding to Phe109 and Gln111, respectively, of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS (21). In the present study, we determined the 2.3 Å resolution crystal structure of the Thermus thermophilus ArgRS, which recognizes the canonical A20. Furthermore, we carried out site-directed mutagenesis and kinetic analyses at the predicted crucial residues for the recognition of A20 to investigate their precise recognition mode.

Materials and Methods

Structure Determination.

The T. thermophilus ArgRS gene (accession number: AJ278815) was overexpressed in the E. coli strain JM109(DE3) (22). The recombinant protein was purified and crystallized, and the crystal structure was solved by multiple isomorphous replacement augmented with anomalous scattering (MIRAS) (22). The atomic model was built in the electron density map by the program o (23). Crystallographic positional and slow-cooling refinements were carried out by the programs x-plor (24) and cns (25) against the 2.3-Å data set collected from the beamline 41XU at SPring-8 (Harima, Japan). Refinement statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Refinement statistics

| Resolution, Å | 50.0–2.3 |

| Rwork, % | 21.5 (23.3) |

| Rfree, % | 24.2 (26.3) |

| rms deviation from ideal values | |

| Bond length, Å | 0.0058 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.16 |

| Dihedral angles, ° | 21.78 |

| Improper angles, ° | 0.86 |

| Average B-factor, Å2 | 38.18 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell (2.38–2.30 Å).

Rwork = ∑|FO − FC|/∑|FO| for the working set reflections (95% of the data) used for the refinement. Rfree = ∑|FO − FC|/∑|FO| for the test set reflections (5% of the data) excluded from the refinement.

Construction of a Docking Model of ArgRS and tRNA.

A docking model of T. thermophilus ArgRS and tRNA was constructed according to the following simple procedures. The structure of the complex of S. cerevisiae ArgRS and tRNAArg (21) was superposed on that of the T. thermophilus ArgRS, based on the Rossmann-fold and α-helix bundle domains, by the program lsqkab (26). Subsequently, the atomic coordinates of the T. thermophilus ArgRS and those of the tRNAArg were merged. No additional operations were performed.

Cloning of the T. thermophilus Major tRNAArg Gene.

A mixture of T. thermophilus tRNAs was extracted from T. thermophilus HB8 cells according to Zubay's method (27), and was fractionated by chromatography on a column of DEAE-Sephadex A50 (pH 7.5). The tRNAs of each fraction were further separated by electrophoresis on denaturing 15% polyacrylamide gels. The arginine-accepting activity of each fraction was monitored with recombinant T. thermophilus ArgRS throughout. The purified T. thermophilus major tRNAArg was labeled with 32P at its 3′-terminus, and was used as a probe for Southern hybridization to T. thermophilus chromosomal DNA digested with several restriction enzymes, resulting in marked hybridization to a PvuII fragment of about 3.3 kb. The 3.3-kb PvuII fragment was cloned into the SmaI site of plasmid pUC118 by colony hybridization. The insert was sequenced and found to include the major portion of the gene encoding the T. thermophilus major tRNAArg (nucleotides 16–76). Because the tRNAArg gene includes a PvuII site, the 5′ portion corresponding to nucleotides 1–15 is missing. The complete sequence of the gene for the major tRNAArg was deduced based on the complementary nature of its acceptor and D stems and the sequence homology with its E. coli homolog, and was later verified by T. thermophilus HB8 genome sequencing (data not shown).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Kinetic Analyses.

The ArgRS mutant genes were made by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis, and were ligated into the vector pK7 (28). The nucleotide sequences of the genes were confirmed by dideoxy sequencing. All of the ArgRS mutants could be purified by the same procedure as that used for the wild-type enzyme (22). The DNA fragment containing the gene for the T. thermophilus major tRNAArg and the T7 promoter sequence, with an artificial BamHI site at the 5′ end and a HindIII site at the 3′ end, was amplified by PCR by using the T. thermophilus chromosomal DNA as the template. The amplified DNA fragment was ligated into the appropriate sites of the vector pUC 118. The in vitro transcription systems for the tRNAArg variants were constructed in a similar way. The pUC118 vectors harboring the genes for the major tRNAArg and its variants were digested with MvaI, and were used for runoff transcription with T7 RNA polymerase. The transcripts were further purified by electrophoresis on denaturing 15% polyacrylamide gels.

The kinetic parameters of the arginylation were determined at 65°C in 100 mM Hepes-NaOH buffer (pH 7.5) containing 30 mM KCl, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 2 mM ATP, 100 μM l-[14C]arginine, 0.05–1.5 μM of the wild-type and mutant ArgRSs, and 1–80 μM of the major tRNAArg transcripts and its variants. Because the background level of l-[14C]arginine incorporation was relatively high and increased depending on the l-[14C]arginine concentration, it was difficult to determine the correct Km value for l-arginine. Therefore, in the present measurement, the l-[14C]arginine concentration was fixed to 100 μM, which is an estimated physiological l-arginine concentration and is higher than that used thus far for the measurement of arginylation kinetics for other ArgRS species.

Because the purification step included a heat treatment at 75°C for 30 min to denature the E. coli proteins, the amount of the E. coli chromosomal ArgRS in the preparation of the recombinant T. thermophilus ArgRS was negligible. Furthermore, the arginylation assay of T. thermophilus ArgRS was carried out at 65°C, and, under these conditions, the aminoacylation activity of E. coli ArgRS was not detectable. Therefore, the contributions of the E. coli chromosomal ArgRS to the aminoacylation activities measured for the present recombinant T. thermophilus ArgRS samples were estimated to be less than 0.001%.

Results and Discussion

Overall Structure of T. thermophilus ArgRS.

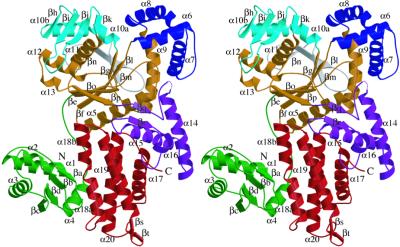

The current model comprises residues 1–397 and 402–592. Residues 398–401, which are in a loop near the “KMSKS” signature motif, were poorly ordered. The size of the T. thermophilus ArgRS is ≈85 Å by 65 Å by 25 Å (Fig. 1). The final model has an Rwork of 21.5% and an Rfree of 24.2% at 2.3 Å resolution, and shows very good geometry, as determined by the program procheck (29): 92.7% and 7.1% of the residues have φ/ψ angles in the “most favored” and “additional allowed regions,” respectively. The structure can be divided into seven regions, which each contain a single domain: the N-terminal α/β globular domain (colored green in Fig. 1), the class-I-specific Rossmann-fold domain (colored brown in Fig. 1), three domains that intervene into the Rossmann-fold domain (colored blue, cyan, and gray, respectively, in Fig. 1), the “stem contact fold (SC-fold)” domain (ref. 30; colored purple in Fig. 1), and the α-helix bundle domain in the C terminus (colored red in Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Ribbon diagram displaying the overall folding of T. thermophilus ArgRS (stereo view). N and C indicate the amino and carboxyl termini, respectively. All of the secondary structures are numbered. All of the graphic figures in the present paper were drawn by using molscript (31) and raster3d (32).

Structural Comparison Between the T. thermophilus and S. cerevisiae ArgRSs.

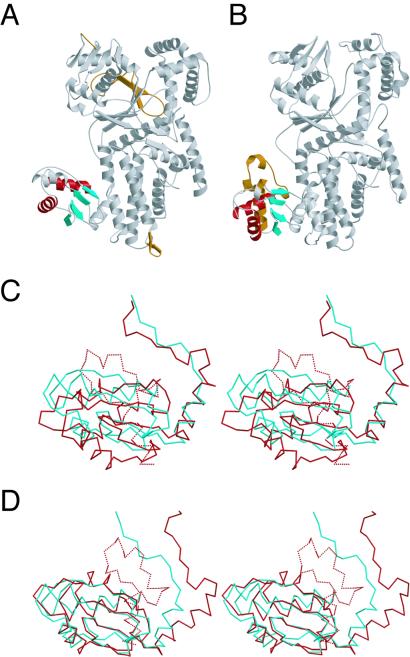

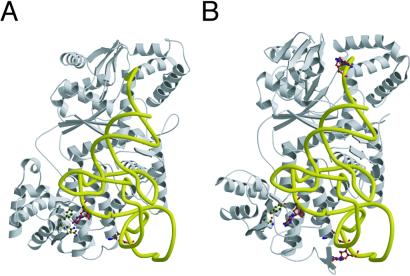

The overall structure of the T. thermophilus ArgRS is similar to that of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS, except for several insertions and domains as described below (Figs. 2 and 3). On the basis of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS⋅tRNAArg complex structure (21), a docking model of the T. thermophilus ArgRS and tRNA was constructed (Fig. 3B). In this docking model, both C35 (the other major identity determinant) and the 3′ adenosine of tRNAArg fit well into the putative recognition pockets on the T. thermophilus ArgRS structure, in the same manner as the S. cerevisiae ArgRS⋅tRNAArg complex (Fig. 3). On the other hand, there are three specific insertions in the T. thermophilus ArgRS structure. First, a short antiparallel β-sheet (βs and βt) is inserted at the end of α19 in the α-helix bundle domain of the T. thermophilus ArgRS (Figs. 1 and 2A). The docking model suggests that the short antiparallel β-sheet of the T. thermophilus ArgRS comes close to position 34 (the first letter of the anticodon) of tRNAArg (Fig. 3B). Second, in the CP domain, which intervenes into the Rossmann-fold domain (31), the loop between βh and βi is elongated by five amino acid residues in the T. thermophilus ArgRS (Fig. 2A). This elongated loop of the T. thermophilus ArgRS is thought to be close to position 73 (the discriminator base) of tRNAArg (Fig. 3B), whereas the discriminator base is a weak identity determinant of E. coli tRNAArg (17). Specific recognition of the discriminator base was not described for the S. cerevisiae ArgRS⋅tRNAArg complex (21). The orientation of the CP domain relative to the Rossmann-fold domain in the T. thermophilus ArgRS structure is different from that in the S. cerevisiae ArgRS⋅tRNAArg complex (Fig. 2 A and B), which is ascribed to the crystal packing effect in the T. thermophilus ArgRS crystals (data not shown). The third insertion of the T. thermophilus ArgRS intervenes between α11 and βo (colored gray in Fig. 1), and extends the β-sheet of the Rossmann fold by a two-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (βl, βm, and βn) at the back of the catalytic site (Fig. 2A). This insertion is species-specific to the T. thermophilus and Pyrococcus horikoshii ArgRSs (data not shown), and may contribute to the thermostability of the catalytic domain. Finally, the N-terminal domain of the T. thermophilus ArgRS has a significantly different structure from that of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS, as described below (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

(A and B) Ribbon diagrams of T. thermophilus ArgRS (A) and S. cerevisiae ArgRS (B). The common antiparallel β-sheets with the lining α helices of the N-terminal domain of the T. thermophilus and S. cerevisiae ArgRSs are colored red for α-helices and cyan for β-sheets, respectively. The additional N-terminal extension of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS and the specific insertions of the T. thermophilus ArgRS are colored brown. (C) Different orientations of the antiparallel β-sheet with the three lining α helices of the N-terminal domain between the T. thermophilus ArgRS (cyan) and the S. cerevisiae ArgRS (red), with the rest of the molecules superimposed (stereo view). The N-terminal extension specific to the S. cerevisiae ArgRS is indicated as dashed lines. (D) Superposition of the antiparallel β-sheet of the N-terminal domain between the T. thermophilus ArgRS (cyan) and the S. cerevisiae ArgRS (red; stereo view).

Figure 3.

(A) The structure of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS complexed with tRNAArg. The tRNA is indicated as a yellow tube. The side chains of Asn106, Phe109, and Gln111, and D20 and C34 are depicted as a ball and stick representation. (B) A docking model of the T. thermophilus ArgRS and tRNA. The side chains of Tyr77 and Asn79, and G34, C35, the discriminator G73, and the predicted A20 are depicted as a ball and stick representation.

Amino Acid Residues Essential for A20 Recognition.

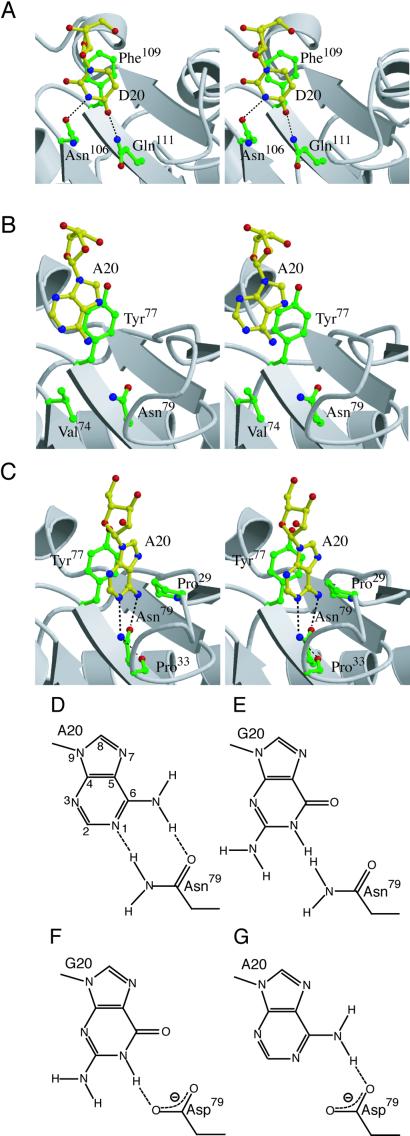

The N-terminal domain (residues 1–102, colored green in Fig. 1) is the most characteristic domain of ArgRS, and is missing in other class-I aaRS structures (20). The S. cerevisiae ArgRS also has a homologous N-terminal domain, designated as an additional domain 1 (Add 1; ref. 20). In the structure of the complex of S. cerevisiae ArgRS and tRNAArg, Add 1 contacts D20 of the cognate tRNAArg. Phe109 of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS is involved in a stacking-type interaction with D20, and Asn106 and Gln111 each interact with D20 by a single hydrogen bond (ref. 21; Figs. 3A and 4A). The sequence alignment of the ArgRSs indicates that the A20-recognizing ArgRSs have the invariant Phe/Tyr and Asn residues (Tyr77 and Asn79 of T. thermophilus ArgRS) at the positions corresponding to Phe109 and Gln111, respectively, of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS (21). By analogy, this invariant Asn residue was suggested to be involved in the interaction with A20 (21).

Figure 4.

(A) Interaction of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS with D20. Hydrogen bonds between D20 and Asn106, and that between D20 and Gln111, are indicated as dashed lines. (B) The docking model of the T. thermophilus ArgRS and tRNA. A20 and the side chains of Val74, Tyr77, and Asn79 are depicted as a ball and stick representation. (C) A model of A20 recognition by Tyr77 and Asn79, based on the present mutagenesis analyses. Putative hydrogen bonds formed between the modeled A20 and Asn79, and that between Asn79 and Pro33, are indicated as dashed lines. (D, E, F, and G) Schematic representations of possible interactions between A20 and Asn79 (D), G20 and Asn79 (E), G20 and Asp79 (F), and A20 and Asp79 (G). Possible hydrogen bonds are indicated as dashed lines.

The N-terminal domain of the T. thermophilus ArgRS folds into a globular structure comprising a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (βa to -d) with four lining α-helices (α1 to -4; Fig. 1). This N-terminal globule is covalently connected to the Rossmann-fold domain by an extended nine-residue linker, and the linker and helix α4 are fixed on the C-terminal α-helix bundle domain through hydrophobic interactions (Fig. 1). On the other hand, the corresponding N-terminal domain of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS has an extension of 33 aa residues at the N terminus. This S. cerevisiae ArgRS-specific extension is extensively involved in the hydrophobic core of the N-terminal domain (Fig. 2 C and D). Because of this significant difference in the N-terminal-domain architecture, the S. cerevisiae ArgRS positions the antiparallel β-sheet with the three α helices, corresponding to the T. thermophilus α1, α2, and α3, in a quite different orientation relative to the last α-helix, corresponding to the T. thermophilus α4 (Fig. 2 C and D). Nevertheless, the former part, consisting of α1–α3 and βa–βd, and the latter part, consisting of α4 and the linker of the T. thermophilus N-terminal domain, separately superpose well on the corresponding parts of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS (Fig. 2 D and C, respectively). Consequently, the orientation of the former part of the N-terminal domain relative to the rest of the entire protein is significantly different between the two ArgRSs, because the latter part of the N-terminal domain is hydrophobically fixed on the C-terminal α-helix bundle domain. This structural difference observed in the N-terminal domain between the T. thermophilus and S. cerevisiae ArgRSs is not likely to be due to the crystal packing.

The two amino acid residues discussed above with respect to the interaction with the nucleotide at position 20 (Tyr77/Asn79 in T. thermophilus and Phe109/Gln111 in S. cerevisiae) are located on one surface of the antiparallel β-sheet (βc and βd in T. thermophilus ArgRS, Fig. 1). In the S. cerevisiae ArgRS⋅tRNAArg complex, D20 directly interacts not only with the two residues Phe109 and Gln111 but also with Asn106 (Fig. 4A). In the docking model of T. thermophilus ArgRS and tRNA, the invariant Tyr77 and Asn79 residues were indeed located in the proximity of A20 (Fig. 3B). However, A20 is not close enough to contact Tyr77 and Asn79 (Figs. 3B and 4B), because of the architectural difference of the N-terminal domain, as described above. If the proposed involvement of the two invariant residues is the case, then either tRNAArg or ArgRS, or both, should change the conformation to make the two residues interact directly with A20. Because the N-terminal domain is tightly folded and fixed to the neighboring α-helix bundle domain, it is likely that the D-loop, which bears A20 in a flipped out orientation, changes its conformation on tRNAArg binding to the enzyme. The putative conformational change should translate and rotate A20 for the proper recognition by Tyr77 and Asn79. Other than the side chain of Asn79, there is no other polar group that might interact with A20. Val74 of the T. thermophilus ArgRS, which is located at the position corresponding to Asn106 of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS, is too far from A20 to be involved in the recognition (Fig. 4B).

Mutational Analyses of the ArgRS.

To validate the proposed model of the A20 recognition by the canonical ArgRSs (21), and to investigate the recognition modes of Tyr77 and Asn79 further, we mutated the two invariant residues in the N-terminal domain. The wild-type T. thermophilus ArgRS arginylated the tRNAArg harboring A20, whereas it did not arginylate the tRNAArg variants with G20, C20, or U20 (Table 2). This result confirmed that A20 actually acts as a major identity element of the T. thermophilus tRNAArg.

Table 2.

Arginylation activities of the wild-type and mutant ArgRS enzymes

| Protein | tRNAArg (A20)

|

tRNAArg (G20)

|

tRNAArg (C20)

|

tRNAArg (U20)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km, μM | Vmax, s−1 | Vmax/Km, relative | Km, μM | Vmax, s−1 | Vmax/Km, relative | Km, μM | Vmax, s−1 | Vmax/Km, relative | Km, μM | Vmax, s−1 | Vmax/Km, relative | |

| WT | 9.8 | 0.67 | 1 | ND* | ND | <0.001† | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 |

| Y77F | 20.4 | 0.66 | 0.47 | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 |

| Y77A | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 |

| N79A | 20.0 | 0.019 | 0.013 | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 |

| N79D | 7.5 | 0.38 | 0.74 | 9.5 | 0.33 | 0.51 | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 |

| N79Q | 25.2 | 0.034 | 0.02 | 19.6 | 0.047 | 0.035 | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 |

| N79E | 12.5 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 9.0 | 0.061 | 0.099 | ND | ND | <0.001 | 19.6 | 0.030 | 0.022 |

| N79K | 8.3 | 0.0024 | 0.0042 | ND | ND | <0.001 | ND | ND | <0.001 | 58.0 | 0.029 | 0.0073 |

| N79R | 21.7 | 0.0069 | 0.0046 | 16.5 | 0.0036 | 0.0032 | ND | ND | <0.001 | 9.3 | 0.0037 | 0.0058 |

ND, Not determined.

The arginylation could not be detected even when the concentration of the enzyme was increased to 5 μM.

The replacement of Tyr77 by Ala resulted in a significant reduction in the arginylation (Table 2), whereas the replacement of Tyr77 by Phe had no serious effect on the arginylation (Table 2). These results indicate that Tyr77 makes a stacking interaction with A20. In addition, the replacement of Asn79 by Ala reduced the arginylation activity for the tRNAArg (Table 2), indicating that Asn79 plays an important role in A20 recognition.

Surprisingly, the N79D mutant equally arginylated tRNAArg transcripts harboring A20 and G20, and the relative arginylation activity was almost the same as that of the wild-type ArgRS for the tRNAArg harboring A20 (Table 2). The mutants of Asn79, such as the N79D mutant, might be highly detrimental to cell growth, because they might arginylate non-cognate tRNAs. This detrimental effect may have acted as the major selective pressure to conserve the invariant Asn residue. The success in the overproduction of these potential misarginylating mutants might be due to the low activity of the T. thermophilus enzymes at the growth temperature of the host E. coli cells (37°C). The arginylation activities of the N79D mutant for the tRNAArg harboring A20 and G20 were significantly higher than that of the N79A mutant. These results indicate that the N79D mutant acquired the ability to interact with G20, instead of having lost the nucleotide specificity for A20.

The replacement of Asn79 by other polar amino acids reduced the arginylation activity for the tRNAArg without exception (Table 2). The amount of the arginylation activity reduction, however, depended on the mutation. For example, the N79R and N79K mutations remarkably reduced the arginylation efficiency, to a rate even lower than that caused by the N79A mutation. The bulky and positively charged side chains of the Arg and Lys residues may destroy the local conformation of the recognition pocket for A20.

It should be noted that the replacement of Tyr77 or Asn79 by other amino acids predominantly affected the Vmax, rather than the Km, in all cases. This tendency corresponds well to the fact that the A20 mutations of E. coli tRNAArg mostly affected Vmax, rather than Km, in the arginylation (16). These results suggest that the A20 recognition mainly contributes to the “enzyme activation,” which may include changes in the spatial arrangement of important residues in the catalytic cleft and/or the CCA terminus of the tRNA.

The Recognition Pocket for A20.

On the basis of the mutational analyses, we constructed a local structural model of the interaction of A20 with Tyr77 and Asn79, by moving A20 toward the two residues (Fig. 4C). The aromatic ring of Tyr77 was thought to make a stacking interaction with the base of A20, and, therefore, the adenosine could be modeled within an appropriate distance for a stacking interaction with Tyr77 (≈3.5 Å distant, Fig. 4C). On the other hand, based on the mutational results of the base-specific interaction between Asn79 and A20, the γ-NH2 and γ-CO groups of Asn79 may form bipartite hydrogen bonds with the N1 and N6, respectively, of A20 (Fig. 4 C and D). Except for Tyr77 and Asn79, the side chain of Pro29 is located at an appropriate distance from the modeled adenosine for a van der Waals interaction (≈3.5 Å distant, Fig. 4C). Therefore, in this case, A20 is probably sandwiched between Tyr77 and Pro29.

This model can explain how A20 is discriminated from guanosine. As shown in Fig. 4E, the γ-NH2 group of Asn79 would clash with the N1 of guanosine, thus precluding the guanosine from being recognized. The side chain of Asn79 may be fixed by a hydrogen bond between the γ-NH2 group of Asn79 and the α-CO group of Pro33 (≈3.2 Å distant, Fig. 4C). Therefore, hydrogen bonds cannot be formed between Asn79 and the guanosine by the rotation of the Asn79 side chain on its Cβ-Cγ axis. Our model of A20 recognition is also consistent with the fact that the N79D mutant efficiently arginylated tRNAArg with G20. The replacement of Asn79 by Asp may remove the steric hindrance caused by the γ-NH2 group, and yet the δ2-O atom of Asp could serve as another hydrogen-bond acceptor for the N1 of the guanosine (Fig. 4F). On the other hand, the replacement of Asn79 by Asp had only a small effect on the arginylation (Table 2). This fact may be ascribed to the distorted orientation of Asn79. The γ-NH2 group of Asn79 is not on the plane of the modeled adenine base, and thus deviates from the ideal position to provide a hydrogen bond with the N1 of the nucleotide (Fig. 4C). Therefore, the γ-NH2 group of Asn79 may have a minor role in the arginylation, as compared with the γ-CO group of Asn79 (Fig. 4 D and G).

The recognition mode of A20 described above is compared with the interaction between D20 and the S. cerevisiae ArgRS (Fig. 4 A and C). In the T. thermophilus case, A20 forms bipartite hydrogen bonds, analogous to Watson-Crick base pairing, with the Asn79 side chain (Fig. 4 C and D). By contrast, in the complex of S. cerevisiae ArgRS and tRNAArg (Fig. 4A), D20 forms only one hydrogen bond with Gln111, which corresponds to the T. thermophilus Asn79, but forms another hydrogen bond with Asn106, which is replaced by Val74 in the T. thermophilus ArgRS. Therefore, the orientation of the A20 base relative to Asn79 of the T. thermophilus ArgRS is slightly different from that of the D base relative to Gln111 of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS. The D20-recognition pocket of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS may recognize C20 by concomitant flipping of the side chain extremities of Asn106 and Gln111, to fulfill the hydrogen bond scheme (21). Furthermore, it appears to be possible for the S. cerevisiae pocket to adopt even A20 in a similar manner, whereas the S. cerevisiae tRNAArg species have U, dihydrouridine (D), or C, but not A, at position 20 (15). Actually, the arginine-accepting activity was not decreased by the replacement of C20 by A in a S. cerevisiae tRNAArg species (18). Therefore, it might be possible that the S. cerevisiae ArgRS has multiple specificities toward position 20 of the tRNA. In contrast, the canonical ArgRSs can recognize only A at this position, because the side chain of the invariant Asn residue (Asn79) is prevented from rotating by a hydrogen bond between the side chain NH2 group and the main chain CO group (of Pro33, as described above; Fig. 4C).

A major unsolved problem is the mechanism by which A20 recognition leads to the enzyme activation that causes the arginylation with such a high discrimination rate. The ongoing structure determination of the complex of T. thermophilus ArgRS and tRNAArg will provide a structural basis for the mechanism of enzyme activation after A20 recognition, as well as a detailed mechanism of A20 recognition.

Acknowledgments

We thank Masayoshi Nakasako, Michiko Konno, and Masami Horikoshi for data collection. We are greatly indebted to Nobuo Kamiya (Institute of Physical and Chemical Research) and Masahide Kawamoto (Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute) for their help in data collection at SPring-8. We thank Jean Cavarelli for providing us the coordinates of the S. cerevisiae ArgRS⋅tRNAArg complex. We also thank Kiyotaka Shiba, Shun-ichi Sekine, Takaho Terada, and Kyoko Saito for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Kouichiro Kodama, Takanori Kigawa, Hitoshi Kurumizaka, and Mikako Shirouzu for their help in the measurement of arginylation kinetics. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Science Research on Priority Areas (09278101 and 11169204) to S.Y. and O.N., respectively, from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, and by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Research Fellowships for Young Scientists (A.S.).

Abbreviations

- aaRS

aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase

- ArgRS

arginyl-tRNA synthetase

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates of the enzyme and the docking model with tRNA have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID codes 1IQ0 and 1IR4, respectively).

See commentary on page 13473.

References

- 1.Giegé R, Sissler M, Florentz C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5017–5035. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavarelli J, Rees B, Ruff M, Thierry J C, Moras D. Nature (London) 1993;362:181–184. doi: 10.1038/362181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruff M, Krishnaswamy S, Boeglin M, Poterszman A, Mitschler A, Podjarny A, Rees B, Thierry J C, Moras D. Science. 1991;252:1682–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.2047877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rould M A, Perona J J, Söll D, Steitz T A. Science. 1989;246:1135–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.2479982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rould M A, Perona J J, Steitz T A. Nature (London) 1991;352:213–218. doi: 10.1038/352213a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silvian L F, Wang J, Steitz T A. Science. 1999;285:1074–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sankaranarayanan R, Dock-Bregeon A C, Romby P, Caillet J, Springer M, Rees B, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B, Moras D. Cell. 1999;97:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80746-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biou V, Yaremchuk A, Tukalo M, Cusack S. Science. 1994;263:1404–1410. doi: 10.1126/science.8128220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soma A, Uchiyama K, Sakamoto T, Maeda M, Himeno H. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:1029–1038. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asahara H, Himeno H, Tamura K, Hasegawa T, Watanabe K, Shimizu M. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:219–229. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breitschopf K, Achsel T, Busch K, Gross H J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3633–3637. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.18.3633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Normanly J, Ogden R C, Horvath S J, Abelson J. Nature (London) 1986;321:213–219. doi: 10.1038/321213a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Normanly J, Ollick T, Abelson J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5680–5684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClain W H, Foss K. Science. 1988;241:1804–1807. doi: 10.1126/science.2459773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sprinzl M, Horn C, Brown M, Ioudovitch A, Steinberg S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:148–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulman L H, Pelka H. Science. 1989;246:1595–1597. doi: 10.1126/science.2688091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamura K, Himeno H, Asahara H, Hasegawa T, Shimizu M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2335–2339. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.9.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu W, Huang Y-W, Eriani G, Gangloff J, Wang E-D, Wang Y-L. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1473:356–362. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(99)00143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McClain W H, Foss K, Jenkins R A, Schneider J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9260–9264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cavarelli J, Delagoutte B, Eriani G, Gangloff J, Moras D. EMBO J. 1998;17:5438–5448. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delagoutte B, Moras D, Cavarelli J. EMBO J. 2000;19:5599–5610. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimada A, Nureki O, Dohmae N, Takio K, Yokoyama S. Acta Crystallogr D. 2001;57:272–275. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900016255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones T A, Zou J-Y, Cowan S W, Kjeldgaard M. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brünger A T. X-PLOR Version 3.1 Manual. London: Yale Univ. Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brünger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, DeLano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. Acta Crystallogr D. 1994;50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zubay G. J Mol Biol. 1962;4:347–356. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(62)80117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kigawa T, Muto Y, Yokoyama S. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:129–134. doi: 10.1007/BF00211776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laskowski R A, MacArthur M W, Moss D S, Thornton J M. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugiura I, Nureki O, Ugaji-Yoshikawa Y, Kuwabara S, Shimada A, Tateno M, Lorber B, Giegé R, Moras D, Yokoyama S, Konno M. Struct Fold Des. 2000;8:197–208. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraulis P J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merrit E A, Bacon D J. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:505–524. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]