Abstract

Organic crystals are of primary importance in pharmaceuticals, functional materials, and biological systems; however, organic crystallization mechanisms are not well-understood. It has been recognized that “nonclassical” organic crystallization from solution involving transient amorphous precursors is ubiquitous. Understanding how these precursors evolve into crystals is a key challenge. Here, we uncover the crystallization mechanisms of two simple aromatic compounds (perylene diimides), employing direct structural imaging by cryogenic electron microscopy. We reveal the continuous evolution of density, morphology, and order during the crystallization of very different amorphous precursors (well-defined aggregates and diffuse dense liquid phase). Crystallization starts from initial densification of the precursors. Subsequent evolution of crystalline order is gradual, involving further densification concurrent with optimization of molecular ordering and morphology. These findings may have implications for the rational design of organic crystals.

Short abstract

A long-sought mechanistic picture of organic crystallization reveals how two dissimilar amorphous precursors gradually transform into crystals.

Introduction

Obtaining a comprehensive picture of how molecular or atomic order evolves during crystallization is a long-standing challenge. It has been recognized recently that “nonclassical” crystallization from solution involving transient amorphous precursor phases1−5 and particle attachment is commonplace.6 Understanding the morphological and structural properties of these precursors, and how they evolve into crystals, is a key challenge in inorganic,7−10 protein,11−14 and organic crystallization.15−18 The mechanistic picture of organic crystallization is lacking, as dissimilarity of the initially formed amorphous phases and how they transform into crystals have not been elucidated.3 Herein, we present a study on the crystallization of common organic dyes—perylene diimides (PDIs). Direct structural imaging of two crystallization processes, which involve very different amorphous precursors (well-defined aggregates and diffuse liquidlike state), elucidates a common mechanism of crystalline order development. We observe that, in both precursor scenarios, PDI crystallization proceeds via initial densification of prenucleation aggregates, followed by gradual ordering concomitant with continuous densification and change in morphology. This mechanistic picture reveals that density, molecular ordering, and morphology are intimately connected and develop gradually, providing a unifying view on how different amorphous precursors convert into crystals.

Results and Discussion

PDI crystallization is of primary importance in industrial pigments and organic electronic devices.19 Simple PDI derivatives 1 and 2 (Figures 1A and 3A) were chosen for our study as prototypical aromatic molecules. These compounds allow observation of stable prenucleation states due to strong hydrophobic interactions in the initially formed aggregates (Figure 1D).20 Their transformation into crystals was studied by electron microscopy imaging (see below). Water/tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent mixtures are used as crystallization media, where the THF is a good solvent for PDIs, which enables to control the stability of the initially formed aggregates. The aggregation-sensitive optical properties of PDI molecules enable spectroscopic follow up of the crystallization process, complementing the insights obtained from imaging.

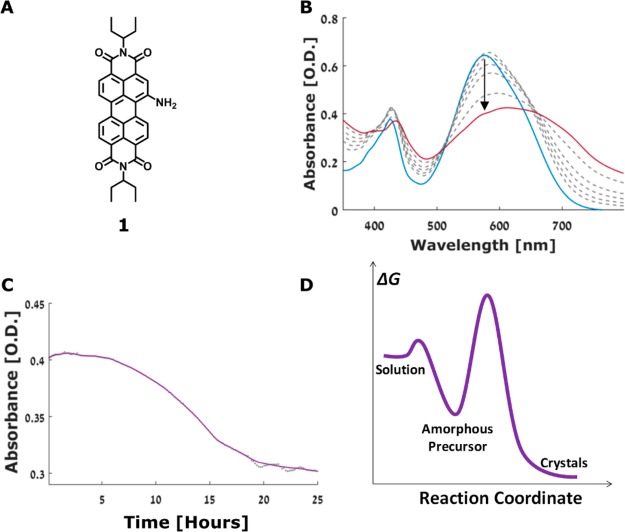

Figure 1.

(A) Molecular structure of 1. (B) UV–vis spectra of 1 recorded during crystallization: 0 (blue), 24 (red), 5, 7, 9, 11, and 15h (top to bottom in gray). (C) Absorption intensity at 530 nm over time (dots—measurements every 5 min). (D) Schematic of the free-energy profile for the crystallization of 1.

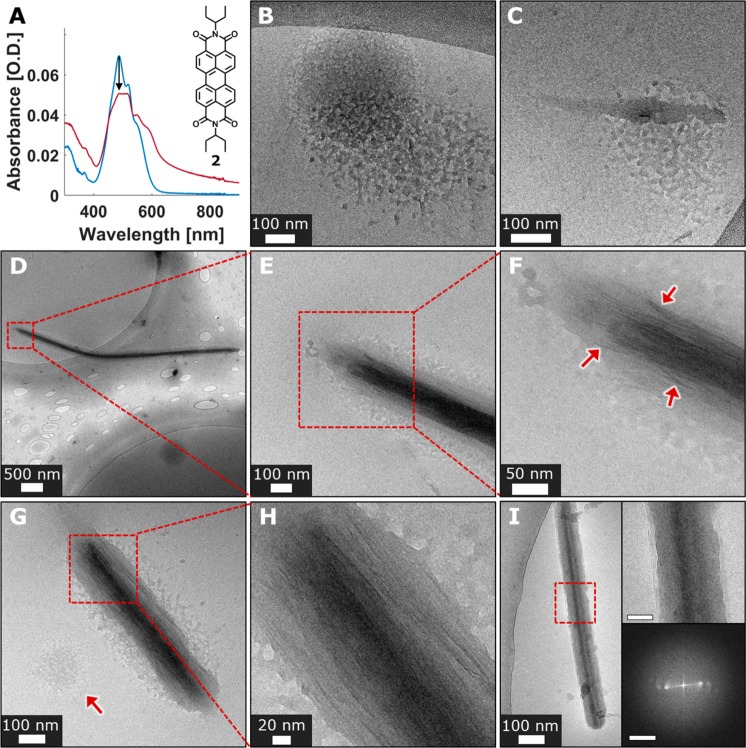

Figure 3.

Cryo-TEM images, crystallization of 2. (A) Molecular structure of compound 2 and its UV–vis spectra in water/THF = 7/3 (v/v) mixture, 10–5 M, immediately after preparation (blue), and after 3 h (red). (B–H) Cryo-TEM images of 2 in water/THF = 1/1 (v/v) mixture, 10–4 M. (B) Unstructured amorphous liquidlike aggregate (30 min of aging). (C) Dense elongated structure forming within the amorphous aggregate (30 min of aging). (D–H) Early order evolution stages (30 min of aging). (D) Underformed needle shrouded in remains of an amorphous aggregate. (E, F) Magnified views of the areas marked in parts D and E, respectively. (F) Fibrous features within the underformed needle are indicated by red arrows. (G) Underformed needle shrouded in an amorphous phase. An amorphous aggregate is indicated by a red arrow. (H) Magnified view of the area marked in G showing fibrous features composing the evolving crystal. (I) 2 in water/THF = 7/3 (v/v) mixture, 10–5 M, showing an underformed needle shrouded in amorphous phase (30 min of aging). Top inset: magnified view of the marked area. Scale bar is 30 nm. Bottom inset: FFT analysis of the marked area showing lattice fringes periodicity of 1.1 and 1.6 nm. Scale bar is 1 nm–1.

Crystallization of 1

Crystallization of compound 1 was induced by a direct addition of a THF solution of 1 into water at 18 °C, resulting in 10–4 M water/THF = 85/15 (v/v) solution (Figure S1). The crystallization was monitored using UV–vis and emission spectroscopies, Hyper-Rayleigh scattering (HRS),21 dynamic light scattering (DLS), and electron microscopy. The UV–vis spectrum exhibits a gradual broadening, red-shift, and decrease in intensity of PDI absorption bands during crystallization (Figure 1B). Strongly broadened red-shifted PDI peaks are due to formation of PDI crystals having extended π-stacks with strong electronic coupling between PDI molecules.22,23 The kinetics at the absorption maximum in UV–vis spectra give rise to a sigmoidal curve typical of nucleation/growth processes (Figure 1C). The lag time is 5–6 h, followed by a growth period of about 9–12 h (Figure 1C). Similar sigmoid kinetic traces are also observed by the emission, HRS, and DLS spectroscopies, as well as by broadening of the UV–vis absorption band (Figure S2). Precipitation starts after 18 h (Figure S1), and most material precipitates after 36 h.

Structural development was further studied using electron microscopy. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging of dried samples of 1 reveal fast formation of spherical aggregates (0–15 min of aging, Figures S3 and S4) having diameters of 51 ± 10 nm and no apparent order. Elongated crystals, several to tens of micrometers long and hundreds of nanometers in width, are observed after 18 h (Figures S5 and S6). Their crystallinity is evident from powder X-ray diffraction (pXRD, Figure S7), electron diffraction (ED, Figure S8), and the periodicity of the lattice fringes observed in TEM images (Figure S6). At the end of the lag time (5–6 h of aging), mostly spheres and a few crystals are observed (Figures S9 and S10). To elucidate the crystallization mechanism we used cryogenic TEM (cryo-TEM) imaging to follow crystallization of 1.24,25 Cryo-TEM revealed round aggregates that formed within minutes of the initial mixing (Figure 2A and Figure S11), in good agreement with the SEM and TEM images of dried samples (Figures S3 and S4). These spherical aggregates had relatively smooth surfaces, and diameters of 60 ± 27 nm. Occasionally, truncated or dented spheres were also observed, suggesting that the round structures are hollow and filled with solvent, based on a lower contrast of interior (Figure 2A and Figure S11). Within 30 min to 1 h, cryo-TEM imaging revealed morphological changes, manifested by apparent squeezing and deviations from the originally smooth globular morphology (Figure 2B,C and Figure S12). The distorted spheres showed higher contrast compared to nonevolved spheres, indicating densification. Cracks and ruptures in some of the distorted spheres (exposing their hollow interior) coincided with the observed change in morphology (Figure 2B, inset). At longer aging times, the distorted densified spheres display initial crystalline order, as made evident by the observation of lattice fringes, and faceting (Figure 2D and Figures S13–S16). With further aging, the evolving aggregates exhibit a more pronounced faceting (at times adopting triangular or rectangular shapes), also developing fiberlike crystalline whiskers (Figure 2E and Figures S17–S19). They feature lattice fringe periodicity of 1.6–1.9 and 1.2 nm (based on FFT, Figures S13–S19), comparable to the lattice fringes (Figures S6 and S20) and the diffraction peaks observed in the final crystals (1.8 and 1.1 nm, from the pXRD, Figure S7). Eventually, only elongated crystals of various widths are observed in solution by cryo-TEM imaging after 24 h (Figure 2F and Figure S20). SEM imaging of the precipitate revealed formation of faceted elongated crystals (10–30 μm long and 100–700 nm width, Figure S5).

Figure 2.

Cryo-TEM images, crystallization of 1. (A) Spherical aggregates formed immediately after sample preparation. (B) Aging 30–50 min, distorted densified spheres are observed (indicated by red arrows). Inset: an example of aggregate densification, scale bar is 50 nm.(C) A faceted intermediate with apparent crystallinity (indicated by a black arrow). Red arrows denote distorted densified spheres. (D) Ruptured aggregate exhibiting crystallinity (4.5 h of aging). Inset: magnified view of the marked area, showing lattice fringes. Scale bar is 20 nm. (E) Fibrous crystals growing from distorted (faceted) spherical cores (5 h of aging). (F) Developed elongated crystals (24 h of aging). Inset (magnified view of the marked area): lattice fringes. Scale bar is 5 nm. Inset: FFT analysis showing periodicity of 0.9 and 1.7 nm. Scale bar is 1 nm–1.

Overall, the crystallization of 1 involves several key stages: (1) formation of amorphous spherical aggregates; (2) their initial densification, leading to nucleation; (3) appearance of crystalline order within the precursor that retains round morphology; and (4) crystal growth occurring via continuous transition from crystalline spheres to elongated faceted crystals. Few cases of fusion of unevolved spherical aggregates with crystals were also detected (Figure S21). UV–vis spectroscopy shows a continuous PDI absorption band broadening during the crystal growth stage (following lag time of 5–6 h, Figure 1B and Figure S2C), indicating a gradual evolution of molecular ordering that leads to stronger electronic coupling between the molecules of 1.22,23 The beginning of the crystallization appears to involve THF desolvation from the aggregates, since high THF content was found to stabilize the amorphous spheres. At higher THF content the spheres, that initially form, are more stable: In water/THF = 7/3 (v/v, 10–4 M) solutions, the spherical aggregates are stable for days (Figure S22), and only small amounts of crystalline products are observed. In water/THF = 1/1 (v/v, 10–4 M) the spheres are stable for months (Figure S23). The THF content also affects the supersaturation level; when the THF content is higher, the effective concentration is lower. In the crystallization of 1, the immediate formation of the spherical aggregates suggests high supersaturation that promotes efficient phase separation. We note that the nature of the initially formed phase and its role in crystallization represent a key question in nonclassical crystallization.3,26 In the case of 1, the initial amorphous phase (the spheres) is relatively stable, resulting in slow nucleation as made evident by kinetic and cryo-TEM studies, consistent with the two-step nucleation theory.1 The high barrier (Figure 1D) implies the need for a considerable reorganization within the spheres to form a nucleus. The densification (shrinking) of the spheres suggests that nucleation takes place in the inner denser parts of the aggregates; however, the precise location of the more ordered regions was not possible to observe directly.

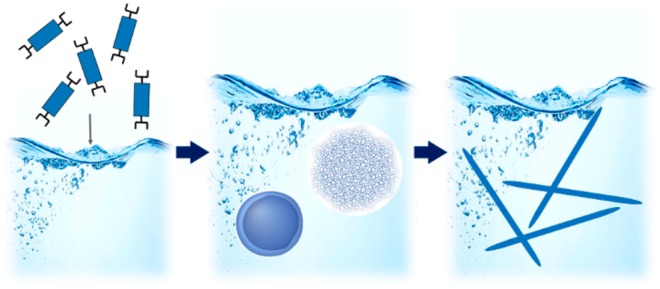

Crystallization of 2

In the case of compound 2 (Figure 3A), crystallization involves precursors very different from those observed for 1. To achieve conditions optimal for the cryo-TEM and spectroscopic studies, a high THF content was required to prevent fast precipitation of 2. Crystallization was induced by a direct addition of water into the THF solution of 2 at 18 °C, yielding the desired water/THF content (1/1 or 7/3, v/v) and concentration. At high THF content (water/THF = 1/1, v/v) and with 2 in a concentration of 10–4 M, some of the material precipitated within several days as crystalline red needles, while most of it remained in solution (Figure S24A), where it is molecularly dissolved (Figure S25), indicating low supersaturation. The crystal structure of the needles was determined by single crystal synchrotron X-ray diffraction and was found to fit a previously published crystal structure of 2 (monoclinic P21/c unit cell),27 featuring π-stacked PDI columns along the crystalline b axis (Figures S26 and S27).

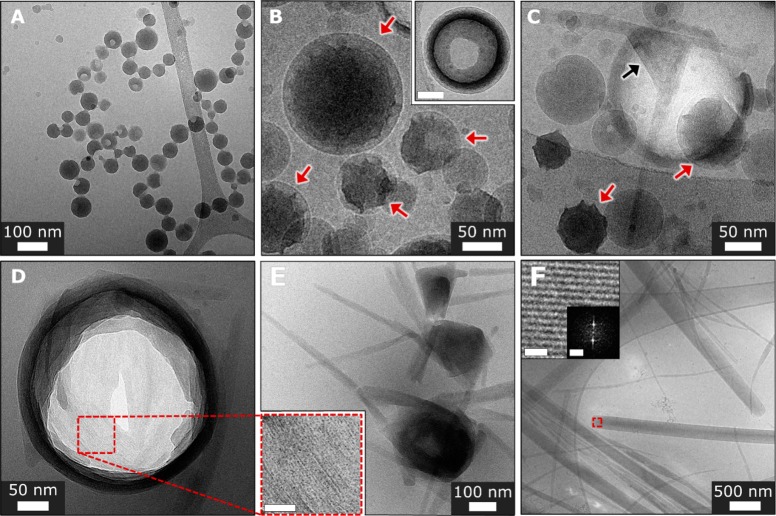

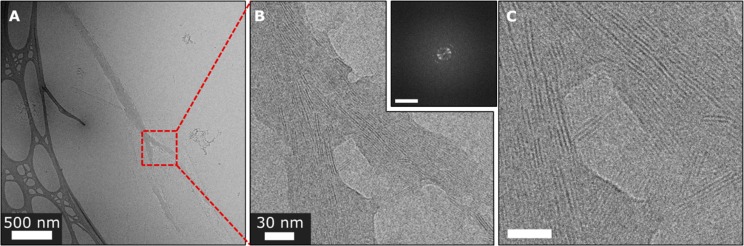

Cryo-TEM imaging at various aging times revealed several distinct morphologies in THF/water = 1/1 (v/v) solution of 2 at 10–4 M concentration. An early diffuse amorphous phase was detected both in a nascent form (Figure 3B) and in a more developed form—in contact with partially developed elongated structures (Figure 3C). The amorphous phase appeared to contain a significant amount of solvent as revealed by its relatively light contrast and disjointed morphology. The elongated structures formed in contact with the amorphous phase (Figure 3C) lack any apparent order as made evident by FFT analysis, but are denser than the surrounding phase as indicated by its darker contrast. A more evolved phase, underdeveloped needles (Figure 3D–H and Figures S29 and S30), was also observed. These lack the sharp faceting characteristic of the final products and are embedded within the diffuse amorphous phase, yet they show regions of periodic lattice fringes of 1.6 nm fitting the (200) spacing of 16.3 Å (Figures S27 and S30). These underdeveloped needles also exhibit poorly aligned fibrous features 2.4 ± 0.7 nm wide (Figure 3F,H, and Figure S29), reflecting an intermediate stage in crystal evolution. The crystallization intermediates in Figure 3D–H and Figures S29 and S30 exhibited an increase in the density gradient from the outer to the inner part. More evolved structures represent a later stage of crystallization, exhibiting various levels of order (Figure 4). They feature domains having lattice fringes of 1.7 and 0.9 nm, yet the latter are somewhat misaligned, while the domains are oriented in different directions. Amorphous regions were also observed (Figure 4B). Overall, the evolving needles reveal the broad spectrum of the ordering, indicating the gradual development of crystallinity. The fully evolved crystalline needles showed faceted surfaces and lattice spacings of 1.7 and 0.9 nm (Figures S31 and S32) that correspond to the {200} and {002} planes of the crystal (Figure S27). During crystallization, the amorphous diffuse phase (Figure 3B,G and Figure S28) represents the prenucleation (dense liquid) state and has no apparent order. It subsequently densifies (Figure 3C) and gradually develops crystalline order (Figures 3D–H and 4).

Figure 4.

Cryo-TEM images of 2 in water/THF (1/1 v/v) solution, 10–4 M. (A) Partly developed needle. (B) Magnified view of the marked area in part A showing misaligned and partly parallel patches of ordered domains. (C) Magnified view of the marked area in part B. Inset: FFT analysis of part C showing periodicities of 1.7 and 0.9 nm with wide angular spread, demonstrating misalignment of lattice fringe patches. Scale bar is 2 nm–1.

At lower THF content, water/THF = 7/3 (v/v) and 2 in concentration of 10–5 M, most of the material precipitated as red needles within 72 h (Figures S24B,C and S33). It exhibited the same structure as that of the crystals observed in the case of water/THF = 1/1 (v/v, Figure S27). The UV–vis spectrum of the freshly prepared water/THF = 7/3 (v/v, 10–5 M) solution of 2 exhibited a broad peak with a 0–0 and 0–1 band pattern typical of π-stacked PDIs (Figure 3A, blue trace). Within 3 h, the spectrum gradually developed a broad absorption band (Figure 3A, red trace) typical of PDI crystals.22,23 Cryo-TEM of the solution after aging time of 20–30 min revealed underformed needles lacking distinct facets and shrouded within an amorphous phase (Figure 3I and Figure S34). These needles showed regions having observable lattice fringes (Figure 3I and Figure S34), and exhibited an increased density gradient from the outer to the inner part, where order appears to be more pronounced in the inner part (Figure 3I and Figure S34). These observations imply that the nucleation takes place at the interior part of the phase, and order is developing outward. Fully developed faceted crystals were observed after 3 h of aging (Figure S35). Thus, in water/THF = 7/3 (v/v, 10–5 M) the crystallization of 2 involves gradual order evolution and apparent densification as indicated by UV–vis and cryo-TEM, similarly to the water/THF = 1/1 (v/v, 1 × 10–4 M) system. The crystallization of 2 reveals a mechanistic resemblance to that of 1, following the same key stages and the same type of energetic path (Figure 1D), yet there are also apparent differences resulting from variations in molecular structures and crystallization conditions. Compound 2 exhibits both a higher symmetry and hydrophobicity compared to 1. Hence, 2 displays a more efficient ordering, bringing the system closer to the final structure. On the other hand, higher THF content in the case of crystallization of 2 results in a more liquidlike, dynamic nature of the initial aggregates, while in the case of 1 the prenucleation aggregates are more “solidlike”, less dynamic, and less ordered.

Crystallization Mechanism

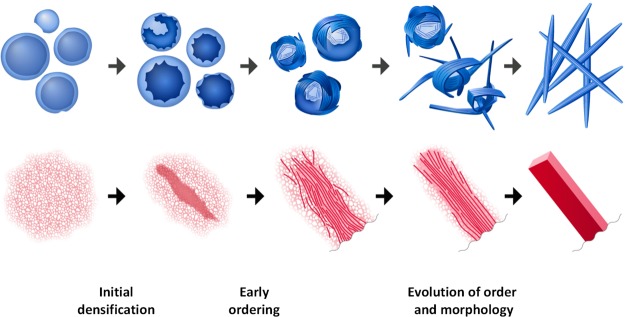

Crystallization paths of 1 and 2 are schematically represented in Figure 5. Although these two processes commence from aggregates that are very different in terms of density and morphology, they exhibit a common general mechanism. It involves three main stages: (1) initial densification; (2) early ordering; and (3) concurrent evolution of order and morphology (Figure 5). The initial densification of the solvent-rich precursors is a critical step, analogously to nonclassical inorganic crystallization.28 Furthermore, crystalline order evolves continuously from the amorphous precursors via partial early ordering followed by order optimization and concurrent morphology change. This mechanistic picture differs significantly from classical crystallization mechanisms, where the initial crystal nucleus is postulated to exhibit the same crystalline structure and density as the final crystal.29 Our findings support two-step nucleation theory that implies initial densification of a solvent-rich precursor phase.1 Furthermore, we elucidate the intrinsic connection between density, molecular ordering, and morphology that evolve gradually.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of crystallization pathways of compounds 1 (top) and 2 (bottom). Three main stages of continuous order development are depicted: initial densification, early ordering, and evolution of molecular order (crystal packing) and morphology.

Conclusions

Nonclassical crystallization of simple aromatic compounds has been studied with high temporal and structural resolution. We show that dissimilar amorphous precursors exist. They transform into crystals via simultaneous and gradual evolution of density, molecular packing, and morphology. These findings provide direct experimental evidence that corroborates the two-step nucleation theory, and further elucidates continuous evolution of crystallinity, in which the final crystalline order gradually develops rather than forms at the nucleation stage. This is of fundamental importance for nonclassical crystallization paradigm, and has not been previously observed in organic systems. Overall, the observed mechanism advances a unifying view of nonclassical organic crystallization, having implications for rational design of organic crystalline materials.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation, Minerva Foundation, Gerhardt M. J. Schmidt Minerva Center for Supramolecular Architectures, and the Helen and Martin Kimmel Center for Molecular Design. The SEM and TEM studies were conducted at the Irving and Cherna Moskowitz Center for Nano and BioNano Imaging (Weizmann Institute of Science).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00289.

Additional materials and methods and figures including photos of the samples solutions, kinetics of crystallization, SEM and TEM, pXRD, electron diffraction image, UV–vis and emission spectra, crystal structure, and cryo-TEM images (PDF)

Author Contributions

⊥ Y.T. and S.R. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Vekilov P. G. Nucleation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2010, 10, 5007–5019. 10.1021/cg1011633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdemir D.; Lee A. Y.; Myerson A. S. Nucleation of Crystals from Solution: Classical and Two-Step Models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 621–629. 10.1021/ar800217x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer D.; Kellermeier M.; Gale J. D.; Bergström L.; Cölfen H. Pre-Nucleation Clusters as Solute Precursors in Crystallisation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 2348–2371. 10.1039/C3CS60451A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolde P. R. t.; Frenkel D. Enhancement of Protein Crystal Nucleation by Critical Density Fluctuations. Science 1997, 277, 1975–1978. 10.1126/science.277.5334.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn D. Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Prenucleation Clusters, Classical and Non-Classical Nucleation. ChemPhysChem 2015, 16, 2069–2075. 10.1002/cphc.201500231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Yoreo J. J.; Gilbert P. U. P. a.; Sommerdijk N. a. J. M.; Penn R. L.; Whitelam S.; Joester D.; Zhang H.; Rimer J. D.; Navrotsky A.; Banfield J. F.; Wallace A. F.; Michel F. M.; Meldrum F. C.; Colfen H.; Dove P. M. Crystallization by Particle Attachment in Synthetic, Biogenic, and Geologic Environments. Science 2015, 349, aaa6760–aaa6760. 10.1126/science.aaa6760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniash E.; Aizenberg J.; Addadi L.; Weiner S. Amorphous Calcium Carbonate Transforms into Calcite during Sea Urchin Larval Spicule Growth. Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. B 1997, 264, 461–465. 10.1098/rspb.1997.0066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner J.; Dey A.; Bomans P. H. H.; Le Coadou C.; Fratzl P.; Sommerdijk N. a J. M.; Faivre D. Nucleation and Growth of Magnetite from Solution. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 310–314. 10.1038/nmat3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupulescu A. I.; Rimer J. D. In Situ Imaging of Silicalite-1 Surface Growth Reveals the Mechanism of Crystallization. Science 2014, 344, 729–732. 10.1126/science.1250984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R. E.; Houben L.; Wolf S. G.; Leitus G.; Lang Z.-L.; Carbó J. J.; Poblet J. M.; Neumann R. Real-Time Molecular Scale Observation of Crystal Formation. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 369–373. 10.1038/nchem.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filobelo L. F.; Galkin O.; Vekilov P. G. Spinodal for the Solution-to-Crystal Phase Transformation. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 014904. 10.1063/1.1943413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleutel M.; Van Driessche A. E. S. Role of Clusters in Nonclassical Nucleation and Growth of Protein Crystals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, E546–E553. 10.1073/pnas.1309320111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter A.; Roosen-Runge F.; Zhang F.; Lotze G.; Jacobs R. M. J.; Schreiber F. Real-Time Observation of Nonclassical Protein Crystallization Kinetics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1485–1491. 10.1021/ja510533x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T.; Kimura Y.; Vekilov P. G.; Furukawa E.; Shirai M.; Matsumoto H.; Van Driessche A. E. S.; Tsukamoto K. Two Types of Amorphous Protein Particles Facilitate Crystal Nucleation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, 2154–2159. 10.1073/pnas.1606948114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidhar Y.; Weissman H.; Tworowski D.; Rybtchinski B. Mechanism of Crystalline Self-Assembly in Aqueous Medium: A Combined Cryo-TEM/Kinetic Study. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20, 10332–10342. 10.1002/chem.201402096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar C.; Dutta S.; Weissman H.; Shimon L. J. W.; Ott H.; Rybtchinski B. Precrystalline Aggregates Enable Control over Organic Crystallization in Solution. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 179–182. 10.1002/anie.201507659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur D.; Politi Y.; Sivan B.; Fratzl P.; Weiner S.; Addadi L. Guanine-Based Photonic Crystals in Fish Scales Form from an Amorphous Precursor. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 388–391. 10.1002/anie.201205336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harano K.; Homma T.; Niimi Y.; Koshino M.; Suenaga K.; Leibler L.; Nakamura E. Heterogeneous Nucleation of Organic Crystals Mediated by Single-Molecule Templates. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 877–881. 10.1038/nmat3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Würthner F.; Saha-Möller C. R.; Fimmel B.; Ogi S.; Leowanawat P.; Schmidt D. Perylene Bisimide Dye Assemblies as Archetype Functional Supramolecular Materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 962–1052. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybtchinski B. Adaptive Supramolecular Nanomaterials Based on Strong Noncovalent Interactions. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6791–6818. 10.1021/nn2025397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenne S.; Grinvald E.; Shirman E.; Neeman L.; Dutta S.; Bar-Elli O.; Ben-Zvi R.; Oksenberg E.; Milko P.; Kalchenko V.; Weissman H.; Oron D.; Rybtchinski B. Self-Assembled Organic Nanocrystals with Strong Nonlinear Optical Response. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 7232–7237. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b02010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett P. E.; Margulies E. A.; Matte H. S. S. R.; Hersam M. C.; Marks T. J.; Wasielewski M. R. Effects of Crystalline Perylenediimide Acceptor Morphology on Optoelectronic Properties and Device Performance. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 3928–3936. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b01230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazmaier P. M.; Hoffmann R. A Theoretical Study of Crystallochromy. Quantum Interference Effects in the Spectra of Perylene Pigments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 9684–9691. 10.1021/ja00100a038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich H.; Frederik P. M.; de With G.; Sommerdijk N. A. J. M. Imaging of Self-Assembled Structures: Interpretation of TEM and Cryo-TEM Images. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7850–7858. 10.1002/anie.201001493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman H.; Rybtchinski B. Noncovalent Self-Assembly in Aqueous Medium: Mechanistic Insights from Time-Resolved Cryogenic Electron Microscopy. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 17, 330–342. 10.1016/j.cocis.2012.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knezic D.; Zaccaro J.; Myerson A. S. Nucleation Induction Time in Levitated Droplets. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 10672–10677. 10.1021/jp049586s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maniukiewicz W.; Bojarska J.; Olczak A.; Dobruchowska E.; Wiatrowski M. 2,9-Di-3-Pentylanthra[1,9- Def:6,5,10- d ′ e ′ f ′]Diisoquinoline-1,3,8,10-Tetrone. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E: Struct. Rep. Online 2010, 66, o2570–o2571. 10.1107/S1600536810036275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihli J.; Wong W. C.; Noel E. H.; Kim Y.-Y.; Kulak A. N.; Christenson H. K.; Duer M. J.; Meldrum F. C. Dehydration and Crystallization of Amorphous Calcium Carbonate in Solution and in Air. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–10. 10.1038/ncomms4169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sear R. P. The Non-Classical Nucleation of Crystals: Microscopic Mechanisms and Applications to Molecular Crystals, Ice and Calcium Carbonate. Int. Mater. Rev. 2012, 57, 328–356. 10.1179/1743280411Y.0000000015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.