Abstract

Background:

Early death after a treatment can be seen as a therapeutic failure. Accurate prediction of patients at risk for early mortality is crucial to avoid unnecessary harm and reducing costs. The goal of our work is two-fold: first, to evaluate the performance of a previously published model for early death in our cohorts. Second, to develop a prognostic model for early death prediction following radiotherapy.

Material and methods:

Patients with NSCLC treated with chemoradiotherapy or radiotherapy alone were included in this study. Four different cohorts from different countries were available for this work (N = 1540). The previous model used age, gender, performance status, tumor stage, income depriv ation, no previous treatment given (yes/no) and body mass index to make predictions. A random forest model was developed by learning on the Maastro cohort (N = 698). The new model used performance status, age, gender, T and N stage, total tumor volume (cc), total tumor dose (Gy) and chemotherapy timing (none, sequential, concurrent) to make predictions. Death within 4 months of receiving the first radiotherapy fraction was used as the outcome.

Results:

Early death rates ranged from 6 to 11% within the four cohorts. The previous model performed with AUC values ranging from 0.54 to 0.64 on the validation cohorts. Our newly developed model had improved AUC values ranging from 0.62 to 0.71 on the validation cohorts.

Conclusions:

Using advanced machine learning methods and informative variables, prognostic models for early mortality can be developed. Development of accurate prognostic tools for early mortality is important to inform patients about treatment options and optimize care.

Introduction

Primary lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide [1]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80–85% of all lung cancers. For non-resectable NSCLC, chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is the standard of care for locally advanced disease. It has been reported that 8% of NSCLC patients die within the first 30 days of systemic anti-cancer treatment (SACT) initiation [2]. In patients who die within a few weeks of radiotherapy initiation, the inconvenience of attending hospital appointments and the side effects may outweigh the benefit of the treatment.

Prognostic models that can identify patients at risk for early mortality are therefore vital to reduce patient burden and treatment costs. Several prognostic factors have been identified, such as performance status [3], weight loss [3], presence of comorbidity [4], chemotherapy use in combination with radiotheraphy (RT) [3], radiation dose [3], tumor volume [5], genetics [6,7] and image features, the socalled radiomics approach [8]. For other factors, such as age and gender, results are contradictory and therefore inconclusive [9,10]. The current gold standard for survival prediction NSCLC patients is the TNM staging system. This system was originally developed to determine patients eligibility for surgery, and not intended to be used in the context of CRT treatment [11]. Prognostic models of survival for nonresectable NSCLC patients receiving CRT are available [5,12]. However, these models focus on 2-year survival, rather than early death. Further shortcomings of these models are that they are trained on relatively small patients datasets with limited heterogeneity and that the added value of more advanced modeling strategies such as random forest is not explored. Therefore, the development of a model for the prediction of early death in NSCLC patients following curativeintent CRT is highly relevant.

In this study, we develop a new model for prediction of early death in locally advanced NSCLC patients. The model is subsequently validated in four independent patient cohorts. In addition, we compared the performance of our model to a reduced version of a previously developed early-death model in the context of SACT by Wallington et al. [2]. We hypothesized that the reduced version of the model published by Wallington et al. [2] will perform above the chance level in predicting early death in our cohorts. Furthermore, we postulated that the new model developed and validated using four international cohorts will show higher discriminative performance than the model developed by Wallington et al. [2].

Material and methods

Data

Clinical data from 1540 lung cancer patients, treated with curative-intent CRT or RT alone were collected and stored in four different medical institutes [698 patients at Maastro Clinic, 147 at University of Michigan (USA), 196 at The Christie Hospital in Manchester (UK) and 499 in Liverpool hospital (Australia)]. Patients were treated for their primary lung tumor and were not diagnosed with another tumor in the 5 years prior to treatment. The patients’ characteristics are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Four-month survival, taken from the first day of radiotherapy, was used as the outcome of this study. Patients with missing data in the validation were excluded. Patients that did not fulfill the planned treatment were included in the study. A consort diagram for this study can be observed in Supplementary Figure S1.

Maastro cohort

The Maastro data were collected under an institutional review board (IRB) approved and registered clinical trial (NCT01949259). Patients were treated between 2004 and 2014. Three different CRT or RT protocol types were administered to the patients in this study. Two hundred twentyseven NSCLC patients were treated according to a new protocol for sequential chemo-radiation, which was introduced in August 2005. The individualized radiation dose ranged from 54.0 to 79.2 Gy, delivered in fractions of 1.8 Gy, twice daily, until the mean lung dose or maximum dose to the spinal cord were reached. Three hundred fifty-seven NSCLC patients received concurrent CRT. A radiation dose of 45 Gy was delivered in fractions of 1.5 Gy, twice daily. This treatment was followed by an individualized dose ranging from 8 to 24 Gy, delivered in fractions of 2 Gy, once daily, again until reaching the normal tissue dose constraints. Fiftythree NSCLC patients received accelerated high dose conformal radiotherapy: 66 Gy in 24 fractions (2.75 Gy per fraction). Some of these patients received chemotherapy. The remaining 61 patients received a treatment regime tailored specifically to the patient. For these patients, total doses ranged from 52.25 to 129.6 Gy and dose per fraction ranged from 2.75 to 5.4 Gy.

Michigan cohort

The Michigan data were collected from prospective protocols under IRB approval (UMCC 2006.040 and UMCC 2007.123). All patients were treated with curative intent in the period between May 2003 and July 2014. One hundred and two received RT to standard doses (60–66 Gy) using once daily fractions of 2 Gy. Seventy eight of these patients received concurrent chemotherapy. Forty-five patients received RT by intensifying doses to persistent PET-avid target volumes during treatment with 2.1–2.85 Gy per fraction up to a total dose of 85.5 Gy in 30 fractions. Forty three out of 45 patients received concurrent chemotherapy.

Manchester cohort

The Manchester cohort consisted of 196 anonymized lung cancer patients with NSCLC, Stage I–IIIB. Studies was conducted under IRB approval. All patients were treated with curative intent in the period between December 2008 and May 2013. Two different protocols were used for treating patients in this dataset. One hundred twenty-one NSCLC patients received 55 Gy in 20 daily fractions (2.75 Gy per fraction), either without chemotherapy or following induction chemotherapy. Seventy-three NSCLC patients received 60–66 Gy in 30–33 daily fractions (2 Gy per fraction) with concurrent radiotherapy.

The remaining two patients received a treatment regime tailored specifically to the patient.

Liverpool cohort

The Liverpool cohort consisted of 499 anonymized lung cancer patients with Stage I–IIIB NSCLC. The study was conducted under IRB approval. All patients were treated with curative intent. Two different protocols were used for treating patients in this dataset. Fifty-three NSCLC patients received 50–55 Gy in 20 daily fractions (2.5–2.75 Gy per fraction) without chemotherapy. Eighty-eight NSCLC patients received 50 55 Gy in 20 or 25 daily fractions (2–2.75 Gy per fraction) without chemotherapy. Forty NSCLC patients received 50–55 Gy in 20 or 25 daily fractions (2–2.75 Gy per fraction) with sequential or concurrent chemotherapy. Three hundred twenty-seven NSCLC patients received 60–66 Gy in 30–33 daily fractions (2 Gy per fraction) either as sole treatment or with concurrent or sequential chemotherapy. Of the remaining 46 patients, 24 received high-fractional dose SABR treatment while 22 patients received a treatment regime tailored specifically to the patient, ranging from 50.4 to 70 Gy with between 15 and 35 fractions.

Variable selection

For variable selection, we have used the largest set of variables that all cohorts had in common and used these to develop a random forest model. The model used performance status, age, gender, T and N stage, total tumor volume (cc), total tumor dose (Gy) and chemo timing (none, sequential, concurrent) to make predictions.

Model comparison

Our newly developed model was compared to the model developed by Wallington et al. [2]. The model by Wallington et al. [2] used age, gender, performance status, tumor stage, income deprivation (ID1, ID2, ID3, ID4, and ID5; based on the English Indices of Deprivation 2010 [13]), no previous treatment given (yes/no) and body mass index (BMI) to make predictions. As income deprivation and BMI were missing in our patient cohorts, we have imputed these with the median to make comparison possible.

Analysis

Random forest is an ensemble machine learning technique that combines several decision trees and has been demonstrated to yield an excellent classification performance [14]. Random forest models used are based on the randomForest package in R (version 3.3.1) [14]. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were made using the pROC package in R [15]. Comparison of ROC curves was done using a method developed by DeLong et al. (1988) [16]. Kaplan–Meier curves were made using the survival package in R [17]. Risk groups were based on partitioning patients in two groups according to survival prediction by the random forest model. Kaplan–Meier curves based on the TNM staging system are included for comparison. Missing values in the training cohort were imputed with a non-parametric missing value imputation method using random forest [18].

Results

The early death rates were 11% for the Maastro clinic cohort, 6% for the Liverpool cohort, 10% for the Manchester cohort and 7% for the Michigan cohort.

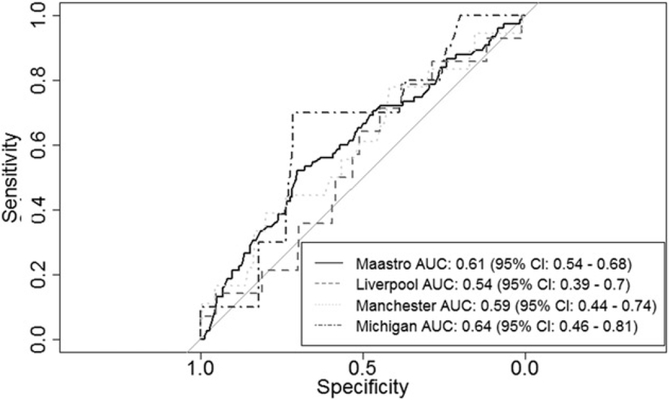

ROC curves for the Wallington model with imputed BMI and income deprivation variables were shown in Figure 1. AUCs range from 0.54 to 0.64. Combining the results for the Manchester, Michigan and Liverpool cohorts gave an overall AUC of 0.55 (95% CI: 0.46–0.63). As the confidence interval overlapped with 0.5, performance of the model did not exceed the chance level.

Figure 1.

ROC curves resulting from validation of the model by Wallington et al. [2] on our patient cohorts.

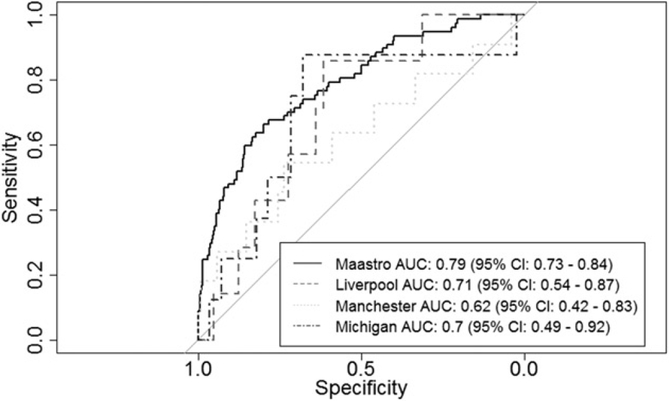

ROC curves for validating the random forest model were shown in Figure 2. AUCs ranged from 0.62 to 0.71. Combining the results for the Manchester, Michigan and Liverpool cohorts gave an overall AUC of 0.66 (95% CI: 0.54–0.77). As the confidence interval did not overlap with 0.5, performance of the model exceeded the chance level. The discriminative performance of the random forest model, compared to the Wallington model with imputed BMI and income deprivation variables, was significantly higher on the Michigan, Manchester and Liverpool validation cohorts combined (p<.05).

Figure 2.

ROC curves resulting from validation of the random forest model trained on the Maastro training cohort.

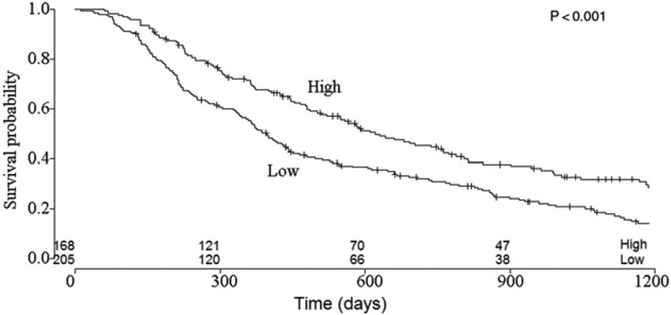

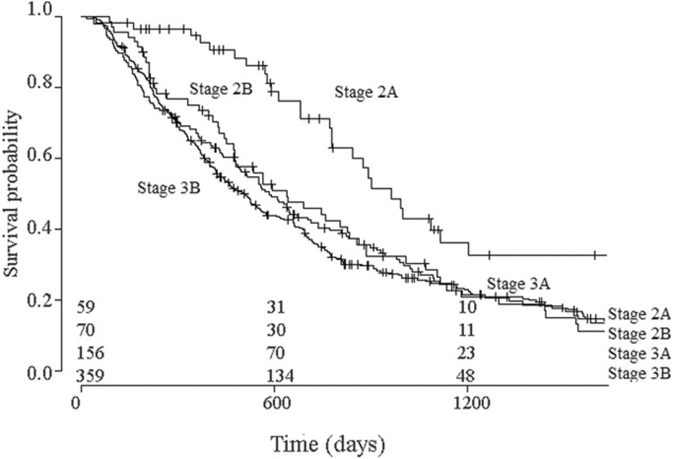

Splitting the validation cohort into two subgroups, resulted in the identification of a high- and low chance of survival group (Figure 3). Median survival in the high survival chance group was 620 days (95% CI: 521–788 days), versus 396 (95% CI: 353–451 days) in the low survival chance group. The 4-month survival rate was 95% (95% CI: 92–99%) for the high survival chance group and 90% (95% CI: 86–94%) for the low survival chance group. A log-rank test on these curves indicated that they were significantly different (p<.001). Figure 4 showed the survival curves for splitting patients based on TNM stage. Median survival was 964 days (95% CI: 780–1708 days) in the Stage 2A group, 638 days (95% CI: 477–856 days) in the Stage 2B group, 583 days (95% CI: 493–737 days) in the Stage 3A group and 510 days (95% CI: 428–574 days) group. The 4-month survival rates were 97% (95% CI: 92–100%) for Stage 2A, 94% (95% CI: 89–99%) for Stage 2B, 89% (95% CI: 84–94%) for Stage 3A and 91% (95% CI: 89–95%) for Stage 3B. The Stage 2A group differs significantly from the other groups (p<.01), however, the other groups were not significantly different from one another (p = .78).

Figure 3.

Survival curves for low and high-risk patient groups identified by the random forest model. The difference between these groups is significant (p<.001).

Figure 4.

Survival curves for patient groups identified TNM staging. The difference between these groups is significant (p<.01).

Discussion

In this study, we developed a random forest model for early death prediction in non-resectable NSCLC patients. We have compared the model performance to the existing model from Wallington et al. [2] for early death prediction in cancer patients following SACT. Our model showed improved AUCs over the Wallington model and can be used to identify high and low risk groups. The model is available at www.predictcancer.org.

There is a paucity of literature on post-RT early mortality relative to the surgical and systemic treatment literature on this topic [2,19]. Previous work on survival prediction for inoperable NSCLC have been developed [12,20], however, these models focus on longer term survival. Our work focuses on identifying patients at high risk of early death. The reduced version model developed by Wallington et al. [2] performs with AUCs >0.5 (i.e., chance) on the validation sets, although the confidence intervals include 0.5 (Figure 1). The AUCs of our random forest model are higher than those of the model of Wallington et al. [2]. Several explanations are plausible for this observation. Firstly, the Wallington model is developed for patients receiving SACT therefore more likely to have advanced disease, whereas our model is based on patients with earlier stage disease receiving RT or CRT. Secondly, different outcome measures are used. In our work, we have used 4-month mortality following the first day of radiotherapy as outcome measure. We have used this outcome measure as it is reasonably close to treatment initiation to make relevance of treatment questionable, while at the same time allowing for sufficient events to occur in our cohorts to make a strong model. Wallington et al. [2] used 30-day mortality following the first day of SACT. Thirdly, the Wallington model uses a logistic regression modeling approach to make predictions. Fourthly, Wallington et al. [2] used a number of variables in their model that were not available in our dataset. Specifically, income deprivation level and BMI (underweight, overweight, obese). The odds ratios for income dependency were relatively small (1.198 for the most income deprived) and did not correlate significantly with the outcome. The odds ratio for BMI underweight was larger (1.752), although it also did not significantly correlate with the outcome (p ¼ .28) [2]. Nonetheless, it is expected that the Wallington model would perform better if these variables were available in our cohorts. In this work, we have used a random forest model. The choice for random forest as modeling strategy is based on experimental work in which it has been shown that random forests are superior to conventional regression models [21].

The model proposed in this study uses readily available clinical variables to make predictions while performing with high discriminative performance for this outcome. Dehing-Oberije et al. [5] have proposed a survival model that outperforms the TNM staging model by including tumor volume and number of positive lymph node stations to make predictions. In another study, it is shown that comprehensive quantification of the tumor using high numbers of imaging features may add value over clinical parameters in predicting outcome for NSCLC patients [8]. Therefore, inclusion of more tumor-specific biomarkers into the model may further enhance model performance.

One of the weaknesses of our study is that we use as our primary outcome 4-month survival from the first day of RT administration. It may be more beneficial to take as an outcome measure 4-month survival from the first day of any treatment. Unfortunately, these dates were not always available in the four available cohorts. Another weakness of this work is that comorbidities were not included as a prognostic variable in the model, as this information was not available in our datasets. There is a significant impact of comorbidities on survival in lung cancer patients [4]. Another weakness of our work is that a rather large portion of data are missing (for example, 46% missing T-stage, in the Maastro cohort). This is a problem that arises when using data originating from routine clinical practice. As more complete datasets give us a better representation of the patients than imputed values, a more complete dataset is expected to produce better results.

Another weakness of our study is that our training cohorts are very heterogeneous in terms of therapy and cancer stages, making it more difficult to capture the diversity of these patients in the model.

The model presented in this study has several weaknesses (as mentioned above). Furthermore, the model leaves room for higher discriminative performance (AUCs range between 0.62 and 0.79). Therefore, we believe this model is not a substitute for clinical judgement by a physician. However, it can be used as a supplement thereof.

In future work, we intend to include variables that could potentially have higher prognostic value, such as radiomics and genomics features to develop more sophisticated models [8,22,23]. Furthermore, as high volumes of patient data are required to capture the heterogeneity of the disease, we intend use the distributed learning approach to have access to further datasets [24–26]. The ultimate aim is to include these models in customized patient decision aids and use them for patient stratification in clinical trials [27,28].

We have developed a prognostic model predicting early mortality in NSCLC patients receiving CRT. The model performs above the chance level in three different validation cohorts (AUCs between 0.62 and 0.79). This model outperforms the previous model.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Interreg grant euroCAT and the Dutch Technology Foundation STW [DuCAT, grant no. 10696; Radiomics STRaTegy, grant no. P14–19], which is the applied science division of Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO); the Technology Programme of the Ministry of Economic Affairs; and the Cancer Research UK Manchester Centre grants (C147/A18083) and (C147/ A25254). The authors also acknowledge financial support from the EU 7th framework program [ARTFORCE, grant no. 257144, REQUITE, grant no. 601826], CTMM-TraIT, EUROSTARS (CloudAtlas), Kankeronderzoekfonds Limburg from the Health Foundation Limburg, Alpe d’HuZes-KWF (DESIGN), The Dutch Cancer Society, NIH P01 CA059827, the European Program H2020–2015-17 [ImmunoSABR, grant no. 733008], the ERC advanced grant [ERC-ADG-2015, grant no. 694812; Hypoximmuno], SME Phase 2 (EU proposal 673780, RAIL).

Footnotes

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Disclosure statement

A.D. is funded by Varian Medical systems for projects other than the one described in this study.

References

- [1].Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wallington M, Saxon EB, Bomb M, et al. 30-day mortality after systemic anticancer treatment for breast and lung cancer in England: a population-based, observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1203–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:330–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Halvorsen TO, Sundstrøm S, Fløtten Ø, et al. Comorbidity and outcomes of concurrent chemo- and radiotherapy in limited disease small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:1349–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dehing-Oberije C, De Ruysscher D, van der Weide H, et al. Tumor volume combined with number of positive lymph node stations is a more important prognostic factor than TNM stage for survival of non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with (chemo)radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70: 1039–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Pøhl M, Olsen KE, Holst R, et al. Keratin 34betaE12/keratin7 expression is a prognostic factor of cancer-specific and overall survival in patients with early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol. 2016;55:167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kvarnbrink S, Karlsson T, Edlund K, et al. LRIG1 is a prognostic biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:1113–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Aerts HJWL,Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RTH, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Comms. 2014;5:4006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hansen O, Schytte T, Nielsen M, et al. Age dependent prognosis in concurrent chemo-radiation of locally advanced NSCLC. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Makita C, Nakamura T, Takada A, et al. High-dose proton beam therapy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: clinical outcomes and prognostic factors. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Berghmans T, Lafitte J-J, Thiriaux J, et al. Survival is better predicted with a new classification of stage III unresectable non-small cell lung carcinoma treated by chemotherapy and radio-therapy. Lung Cancer. 2004;45:339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pöttgen C, Eberhardt W, Stamatis G, et al. Definitive radiochemo-therapy versus surgery within multimodality treatment in stage III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) - a cumulative meta-analysis of the randomized evidence. Oncotarget. 2017;8: 41670–41678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Leeser R English indices of deprivation 2010: A London perspective. Gt. Lond. Auth 2011;232. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Breiman L Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Therneau T, Lumley T. Survival: survival analysis, including penalised likelihood. R package version. 2.36–5; 2011. Available from: http://ftp.auckland.ac.nz/software/CRAN/doc/packages/survival.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stekhoven DJ, Bühlmann P. MissForest-non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28: 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Myrdal G, Gustafsson G, Lambe M, et al. Outcome after lung cancer surgery. Factors predicting early mortality and major morbidity. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:694–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Dehing-Oberije C, Yu S, De Ruysscher D, et al. Development and external validation of prognostic model for 2-year survival of nonsmall-cell lung cancer patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Caruana R, Niculescu-Mizil A. An empirical comparison of supervised learning algorithms. Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning. Pittsburgh (PA); 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Leijenaar RTH, Carvalho S, Hoebers FJP, et al. External validation of a prognostic CT-based radiomic signature in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:1423–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lambin P, Zindler J, Vanneste B, et al. Modern clinical research: How rapid learning health care and cohort multiple randomised clinical trials complement traditional evidence based medicine. Acta Oncol. 2015;54:1289–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jochems A, Deist TM, van Soest J, et al. Distributed learning: developing a predictive model based on data from multiple hospitals without data leaving the hospital - a real life proof of concept. Radiother Oncol. 2016;121:459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jochems A, Deist TM, El Naqa I, et al. Developing and validating a survival prediction model for NSCLC patients through distributed learning across 3 countries. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;99:344–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Deist TM, Jochems A, van Soest J, et al. Infrastructure and distributed learning methodology for privacy-preserving multi-centric rapid learning health care: euroCAT. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2017;4:24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lambin P, Zindler J, Vanneste BG, et al. Decision support systems for personalized and participative radiation oncology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;109:131–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lambin P, van Stiphout RGPM, Starmans MHW, et al. Predicting outcomes in radiation oncology – multifactorial decision support systems. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:27–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.