Abstract

Background

Listeria monocytogenes as the main causative agent of human listeriosis is an intracellular bacterium that has the capability to infect a wide range of cell types. Human listeriosis is a sporadic foodborne disease, which is epidemiologically linked with consumption of contaminated food products. Listeriosis may range from mild and self-limiting diseases in healthy people to severe systemic infections in susceptible populations. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in food resources and human samples from Iran.

Methods

A systematic search was performed by using electronic databases from papers that were published by Iranian authors Since January of 2000 to the end of April 2017. Then, 47 publications which met our inclusion criteria were selected for data extraction and analysis by Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software.

Results

The pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes in human origin was 10% (95% CI: 7–12%) ranging from 0 to 28%. The prevalence of L. monocytogenes in animals was estimated at 7% (95% CI: 4–10%) ranging from 1 to 18%. Moreover, the pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes in Iranian food samples was estimated at 4% (95% CI: 3–5%) ranging from 0 to 50%. From those 12 studies which reported the distribution of L. monocytogenes serotypes, it was concluded that 4b, 1/2a, and 1/2b were the most prevalent serotypes.

Conclusions

The prevalence of L. monocytogenes and prevalent serotypes in Iran are comparable with other parts of the world. Although the overall prevalence of human cross-contamination origin was low, awareness about the source of contamination is very important because of the higher incidence of infections in susceptible groups.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12889-018-5966-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Listeria monocytogenes, Food pathogen, Listeriosis, Meta-analysis, Iran

Background

Listeria is ubiquitous Gram-positive bacteria, which are rod-shaped, facultative anaerobic, and non-spore forming, with a low C + G content [1]. The genus Listeria is composed of several species, of which Listeria monocytogenes is an opportunistic pathogen of humans and animals [1]. Due to ubiquitous nature of Listeria spp., and their unique ability to survive across a broad range of environmental stress including pH, temperature, and salt, they are considered as important foodborne pathogens [2].

L. monocytogenes as the main causative agent of human listeriosis is an intracellular bacterium that has the capability to infect a wide range of cell types and cross the intestinal, blood-brain and placental barriers [3]. Human listeriosis is a sporadic foodborne disease, which is epidemiologically linked with consumption of contaminated food products [4]. In human, listeriosis may range from a mild and self-limiting flu-like sickness or febrile gastroenteritis in healthy people to severe systemic infections including meningitis, septicemia, and abortion in susceptible people [3]. High-risk individuals are the pregnant women, neonates, elderly, immunocompromised individuals and adults with malignancy [5]. Listeriosis can be a serious disease with an approximate 20% mortality; that case–fatality rate may increase in groups at highest risk [4]. Regarding the wide distribution of L. monocytogenes in food resource and high fatality rate of listeriosis, L. monocytogenes has been considered as a major public health concern [1].

Variation in Iranian food tastes results in consumption of different kinds of foods, which may be considered as a risk factor of listeriosis outbreaks. Despite some local information on the prevalence of Listeria spp. in various food resources in Iran, there is no comprehensive data available on its prevalence to estimate the burden of L. monocytogenes. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in food resources and human samples from Iran by using a systematic review and meta-analysis based method. This finding can provide good epidemiological background contributing to the international data of L. monocytogenes distribution.

Methods

Search strategies

A systematic literature search was conducted in the Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar electronic databases from papers that were published by Iranian authors since January of 2000 to the end of April 2017. The following terms, “Listeriosis” or “Listeria” or “L. monocytogenes”, in combination with “Food”, “Animal”, “Human”, and “Iran” were searched as scientific keywords in the present survey both separately and simultaneously in March and April 2017.

Selection criteria and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently screened the databases with the related keywords and reviewed the titles, abstracts, and full texts to determine the articles which met the inclusion criteria; any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The articles published in English or Persian language with English abstract which indexed in Pubmed or Scopus and had met the inclusion criteria were considered in our survey: standard methods (Culture methods, the results based on antibodies (ELISA) and molecular techniques) were used for Listeria detection, present data on the prevalence of L. monocytogenes, and samples were collected from foods or clinical samples. The criteria for identifying Iranian authors were the author or location of the work and also affiliations of authors. Additionally, research that has been conducted by non-Iranian authors on the Iranian population or samples were also assessed. Studies that did not use standardized methods, the sample size was less than 10 isolates, duplicate reports, and articles, samples obtained from environment sources or the origin of samples was unclear in them, articles that were written in Persian with Persian abstract and studies which did not detect L. monocytogenes were excluded. The quality of eligible studies was judged independently by two authors in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute. Eventually, the studies that obtained more than 60% were included in this study [6].

Data extraction

The following details were extracted for each of the included studies: the first author’s name, the time of performing the study, publication date, the study setting, sample size, source of isolation, the frequency of Listeria spp., and L. monocytogenes serotypes.

Statistical analysis

To estimate the overall prevalence meta-analyses, “metaprop program” in STATA version 14.0 (STATA, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software was used [7]. Meta-analysis was performed by using the random-effects model to estimate the pooled prevalence and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical heterogeneity groups were estimated using the Cochran Chi-square test and the Cochrane-I2. The funnel plot, Begg’s rank correlation test, and Egger’s weighted regression tests were used to evaluate possible publication bias (P < 0.05 was considered as an indication of a statistically significant publication bias). Possible sources of heterogeneity were evaluated by sensitivity analysis, meta-regression and subgroup analysis based on the location of the study and diagnostic methods [8, 9]. Sensitivity analysis was applied to determine that the exclusion of any study has a significant effect on the estimated pooled prevalence while ignoring each individual one. The present study designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Additional file 1).

Results

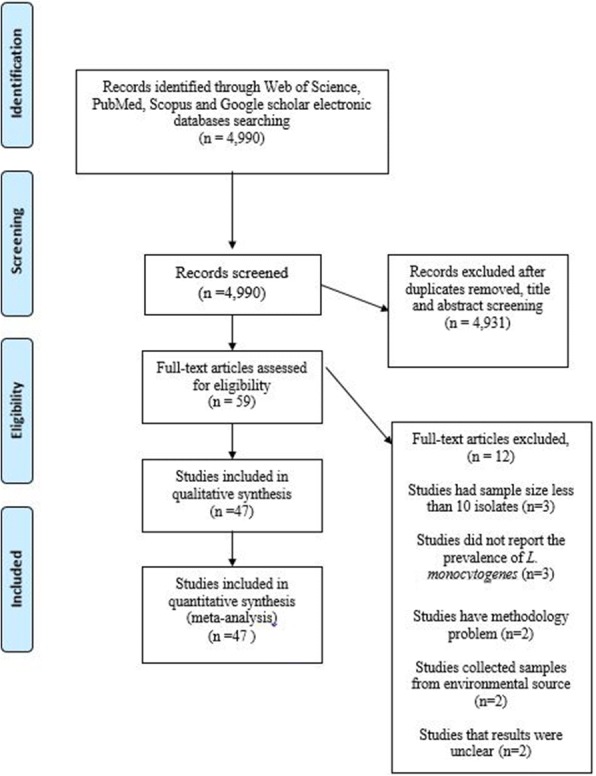

The database search yielded 4990 citations. Among them, 4931 were removed by index, title and abstract screening and 59 were accessed in full text. Of 59 reviewed studies, three studies had a sample size less than 10 isolates, three studies did not report the prevalence of L. monocytogenes, two studies had a methodological problem, two studies collected samples from environment sources, and results of two studies were unclear. Finally, 47 studies matched with eligibility criteria and were subjected to meta-analysis, [2–4, 10–53]. However, out of 47 included studies, three studies reported prevalence in animals and/ humans and/food, simultaneously. The searching procedure for selection of eligible studies is demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review

The full results of the included articles, sample size, the prevalence of L. monocytogenes and predominant serotypes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author | Publication year | Years of study | City or Province/Region | Diagnostic method | Sample source | Types food/animal species/Human | Study design | Sample size | L. monocytogenes | Predominant serotypes | L. innocua | Total | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firouzi et al. | 2000 | UN | Shiraz/South | Culture | Human | Slaughter houses | Cross sectional | 130 | 0 | – | 0 | 3 | 6 |

| Akhondzadeh Basti et al. | 2004 | UN | Tehran and Guilan/North | Culture | Food | Fresh fish, salted and smoked fish | Cross sectional | 120 | 4 | 4b | – | – | 7 |

| Moshtaghi et al. | 2007 | 2005 | Shahrekord/Central | Culture | Food | Raw milk | Cross sectional | 500 | 8 | 4b | 3 | 11 | 8 |

| Rahimi et al. | 2008 | 2006–2007 | Isfahan/Central | Culture | Animal | Cattle | Cross sectional | 200 | 6 | – | – | – | 9 |

| Jalali et al. | 2008 | 2003–2005 | Isfahan/ Central | PCR | Food | Meat, diary, vegetables products ready to eat food | Cross sectional | 461 | 7 | – | 13 | 27 | 4 |

| Jamshidi et al. | 2009 | 2002–2003 | Bandar Abbas/South | Serology | Human | ‘Spontaneous abortion, control group | Case-control study | 450 | 124 | – | – | – | 10 |

| Jami et al. | 2010 | 2008 | Mashhad/Northeast | PCR | Food | Raw milk | Cross sectional | 100 | 4 | – | – | – | 11 |

| Rahimi et al. | 2010 | 2007–2009 | Isfahan/Central | PCR | Food | Milk,dairy products | Cross sectional | 594 | 18 | – | 32 | 55 | 12 |

| Mahmoodi et al. | 2010 | UN | Noorabad/South | Culture | Food | Raw milk, White cheese, yoghurt | Cross sectional | 360 | 6 | – | – | – | 13 |

| Lotfollahi et al. | 2011 | 2009–2010 | Tehran/North | Culture | Human | Spontaneous abortions | Cross sectional | 100 | 9 | – | – | – | 14 |

| Rahimi et al. | 2011 | UN | Tehran/North | Culture | Human | Pregnant mothers | Cross sectional | 512 | 5 | – | – | – | 15 |

| Rahimi et al. | 2011 | 2009–2010 | Isfahan and Shahrekord/Central | PCR | Food | Sea food | Cross sectional- | 264 | 5 | – | 15 | 20 | 16 |

| Ghasemian Safaei et al. | 2011 | 2008 | Shahrekord/Central | Culture | Food | Eggs | Cross sectional | 100 | 0 | – | – | – | 17 |

| Goudarzi et al. | 2012 | 2011 | Karaj/North | PCR | Human | Women with septic abortion | Cross sectional | 87 | 12 | – | – | – | 18 |

| Fallah et al. | 2012 | 2010–2011 | Shahrekord/Central | PCR | Food | Poultry product | Cross sectional | 402 | 52 | 4b, 1/2a, 1/2b, 1/2c | 62 | 134 | 2 |

| Zarei et al. | 2012 | UN | Ahvaz/Southwest | PCR | Food | Raw/fresh,frozen, and ready-to-eat (RTE) seafood | Cross sectional | 245 | 2 | – | – | – | 19 |

| Hosseinzadeh et al. | 2012 | 2009 | Shiraz/South | PCR | Animal | Poultry flocks | Cross sectional | 100 | 7 | – | – | – | 20 |

| Safarpoor Dehkordi et al. | 2012 | 2011 | Various parts of Iran | Real-Time PCR | Food | Milk | Cross sectional- | 596 | 69 | – | – | – | 21 |

| Animal | Vaginal swab/Urine samples | 1575 | 158 | ||||||||||

| Rahimi et al. | 2012 | 2009–2010 | Chahar Mahal & Bakhtiyari/Central and South | Culture and PCR | Food | Dairy products | Cross sectional | 290 | 5 | – | 14 | 21 | 22 |

| Rahimi et al. | 2012 | 2010–2011 | Various parts of Iran | PCR | Food | Raw meats | Cross sectional | 1107 | 27 | – | 98 | 141 | 23 |

| Seifi et al. | 2012 | 2009–2010 | North and west | PCR | Animal | Broiler fl ocks | Cross sectional | 490 | 44 | – | – | – | 24 |

| Fallah et al. | 2013 | 2011–2012 | Shahrekord/ Central | PCR | Food | Raw and RTE seafood product | Cross sectional | 462 | 35 | 1/2a, 4b, 1/2c, 1/2b, 4c | – | – | 25 |

| Jamali et al. | 2013a | 2008–2010 | Tehran/North | PCR | Food | Raw milk | Cross sectional | 446 | 18 | 1/2a, 3a; 1/2c, 3c; 4b, 4d, 4e | 48 | 83 | 26 |

| Jamali et al. | 2013b | 2008–2010 | Tehran/North | PCR | Food | Milk | Cross sectional | 207 | 17 | (4b, 4d or 4e), (1/2a or 3a), (1/2b, 3b or 7), (1/2c or 3c) | 3 | 21 | 27 |

| Sohrabi et al. | 2013 | UN | Isfahan/Central | Culture | Food | Poultry meat | Cross sectional | 52 | 1 | – | 11 | 12 | 28 |

| Vahedi et al. | 2013 | 2011 | Sari/North | Culture | Food | Milk | Cross sectional | 200 | 0 | – | – | – | 29 |

| Momtaz et al. | 2013 | 2010–2011 | Isfahan and Shahrekord/Central | PCR | Food | Fresh fish/shrimp samples | Cross sectional | 300 | 18 | 4b, 1/2b, 1/2a | 2 | 24 | 30 |

| Salehian et al. | 2013 | 2012 | Sari/North | Culture | Food | Traditional ice cream | Cross sectional | 50 | 1 | – | – | 31 | |

| Zarei et al. | 2013 | UN | Ahvaz/ Southwest | PCR | Food | Beef, buffalo and lamb meats | Cross sectional | 210 | 7 | – | – | – | 32 |

| Akya et al. | 2013 | UN | Kermanshah/West | Culture | Food | Dairy, meat, products,RTE | Cross sectional | 530 | 3 | – | 56 | 66 | 33 |

| Shakib et al. | 2013 | UN | Lorestan/West | PCR | Human | Pregnant women | Cross sectional | 100 | 0 | – | – | – | 34 |

| Rahimi et al. | 2014 | 2010–2011 | Fars and Khuzestan/South and Southwest | PCR | Food | Bulk milk, camel, Water, buffalo, ovine, caprine, | Cross sectional | 260 | 7 | – | 13 | 27 | 3 |

| Eslami et al. | 2014 | 2012–2013 | Tehran/North | PCR | Human | Women with abortion | Cross sectional | 96 | 16 | – | – | – | 35 |

| Alidoosti et al. | 2014 | 2012 | Isfahan/Central | Culture | Animal | domestic dogs | 92 | 1 | 1/2b | – | – | 36 | |

| Jamali et al. | 2014 | 2008–2010 | Tehran/North | Culture | Animal | Duck, goose intestinal contents | Cross sectional | 471 | 19 | – | 5 | 58 | 37 |

| Moosavy et al. | 2014 | UN | Tabriz/Northwest | Culture | Food | Raw milk | Cross sectional | 18 | 9 | – | – | – | 38 |

| Haghi et al. | 2015 | 2014 | Zanjan/West | PCR | Food | Bovine milk, ovine milk | Cross sectional | 60 | 0 | – | – | – | 39 |

| Haghroosta et al. | 2015 | UN | Ahvaz/ Southwest | Serologic | Human | Pregnant women with spontaneous abortion and healthy pregnant women | Cross sectional | 180 | 43 | – | – | – | 40 |

| Jamali et al. | 2015 | 2012–2014 | Mazandaran/North | PCR | Food | Raw fish | Cross sectional | 488 | 104 | 1/2a, 4b, 1/2b | 34 | 37 | 41 |

| Soltan Dallal et al. | 2015 | 2013 | Tehran/North | Culture | Food | Vegetables, salads | Cross sectional | 200 | 1 | – | – | 48 | 42 |

| Mashak et al. | 2015 | 2011–2012 | Tehran/North | Culture | Food | Fresh, frozen meats | Cross sectional | 410 | 115 | 1/2a, 4b, 4c, 3b | – | – | 43 |

| Mansouri-Najand et al. | 2015 | 2011 | Kerman/Central | PCR | Food | Raw milk | Cross sectional | 100 | 5 | – | – | – | 44 |

| Pourkaveh et al. | 2016 | 2015 | Tehran/North | PCR | Human | Women with spontaneous abortion | Cross sectional | 317 | 54 | – | – | – | 45 |

| Abdollahzadeh et al. | 2016 | 2014–2015 | Karaj and Tehran/North | PCR | Food | Fish, shrimp, RTE seafood | Cross sectional | 201 | 5 | 1/2b, 3b, 7, 1/2a, 3a | – | 18 | 46 |

| Pournajaf et al. | 2016 | 2012–2015 | Tehran/North | PCR | Human | Patients with spontaneous abortions | Cross sectional | 170 | 14 | – | – | – | 47 |

| Food | Dairy products/meat, | 317 | 20 | ||||||||||

| Animal | Domestic animals | 130 | 12 | ||||||||||

| Zeinali et al. | 2017 | 2013 | Mashhad/North east | PCR | Animal | Fresh chicken carcasses | Cross sectional | 200 | 36 | – | 23 | 80 | 48 |

| Lotfollahi et al. | 2017 | 2013–2015 | Tabriz/North west | PCR | Food | Sausage, milk, cheese, chicken, meat | Cross sectional | 267 | 8 | (1/2c or 3c), (4b, 4d or 4e), (1/2a or 3a) | – | – | 49 |

| Human | Pregnant woman with a abortion | 125 | 11 | ||||||||||

| Animal | Goat and sheep carcasses | 50 | 3 |

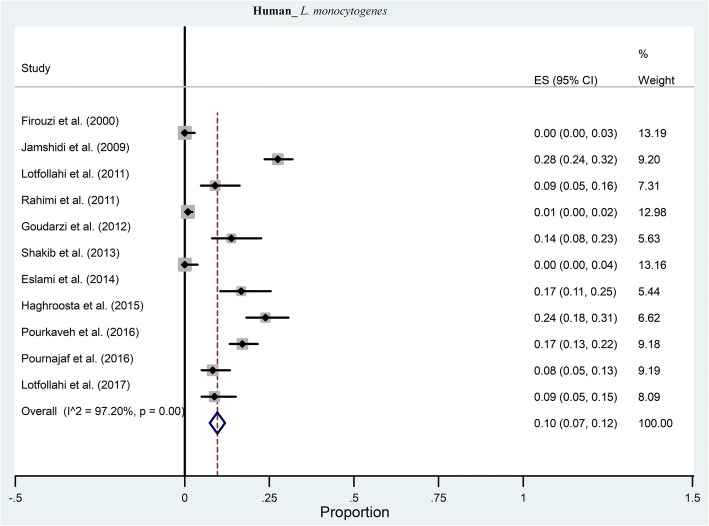

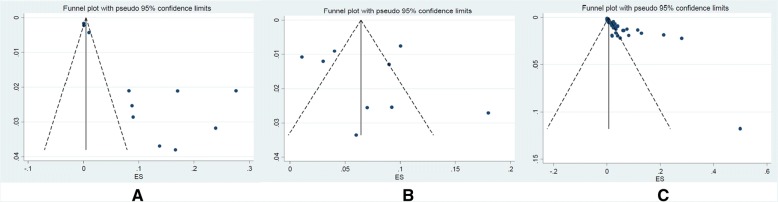

Eleven studies investigated the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in humans. From those studies, the pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes was 10% (95% CI: 7–12%) ranging from 0 to 28% (Fig. 2). There was a significant heterogeneity among the 11 studies (χ2 = 331.98; p < 0.001; I2 = 97.2%). The funnel plot for publication bias showed evidence of asymmetry. Additionally, Begg’s and Egger’s tests were performed to quantitatively evaluate the publication biases. According to the results of Begg’s test (z = 1.48, p = 0.02) and Egger’s test (t = 5.21, p < 0.001) a significant publication bias was observed.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of L. monocytogenes prevalence in human

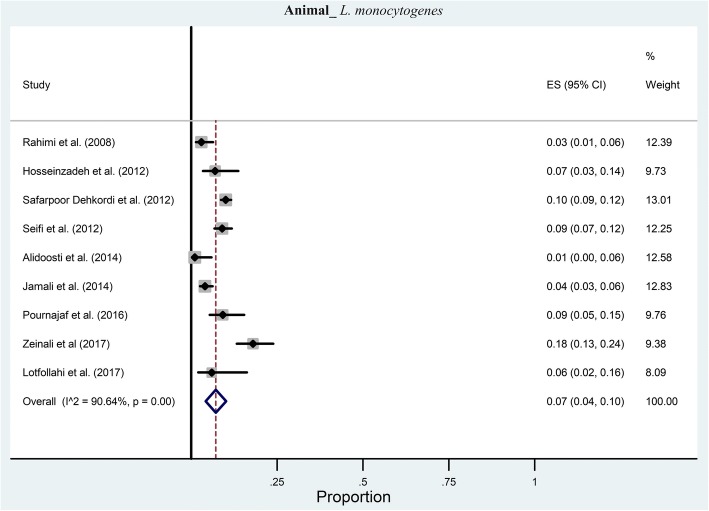

According to the included publications, in nine studies the prevalence of L. monocytogenes was investigated in animals. The pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes was estimated at 7% (95% CI: 4–10%) ranging from 1 to 18% (Fig. 3). There was a significant heterogeneity among the nine studies (χ2 = 85.46; p < 0.001; I2 = 90.64%). The symmetric funnel plot showed no evidence of publication bias and confirmed by the results of Begg’s test (z = 0.21, p = 0.835) and Egger’s test (t = 1.62, p = 0.116).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of L. monocytogenes prevalence in animals

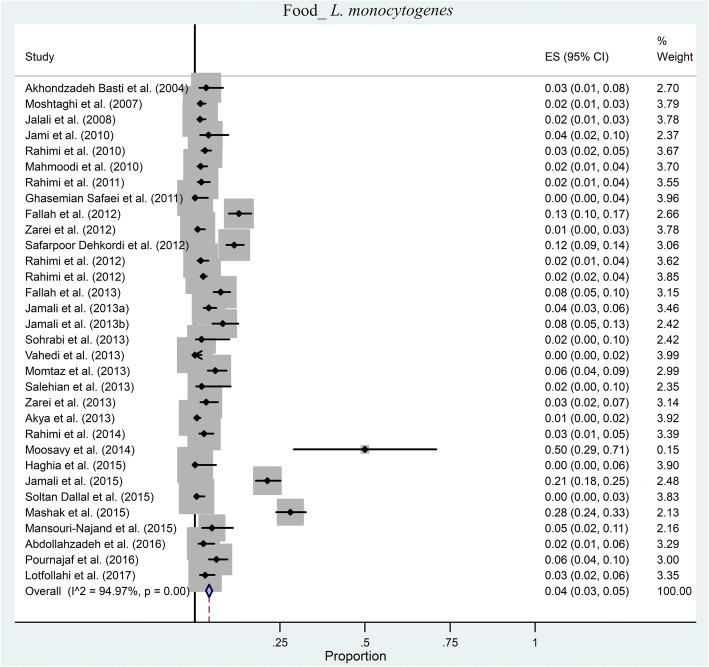

We found 32 articles which investigated the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in foods samples. The pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes in Iranian food samples was estimated at 4% (95% CI: 3–5%) ranging from 0 to 50% (Fig. 4). Based on Q statistic and the I2 index heterogeneity was significant (χ2 = 573.757; p < 0.001; I2 = 94.97%). There was evidence of strong publication bias from the funnel plot of the included articles (Fig. 5); it was confirmed by Begg’s rank correlation analysis (z = 3.73, p < 0.001). However, Egger’s regression analysis showed a significant publication bias (t = 1.62, p = 0.116).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis of L. monocytogenes prevalence in foods

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot of publication bias for the included studies related to a Human, b Animal, and c Food

Of the totally included articles, only in 12 studies the distribution of L. monocytogenes serotypes was reported. From those studies, it was concluded that 4b, 1/2a, and 1/2b were the most prevalent serotype. Furthermore, the pooled prevalence of L. inocua was 5.6% ranging from 4.1 to 7.7%.

The results of subgroup analysis based on geographic location in human samples showed that pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes was 14% (95% CI: 1–36%; n = 3 studies), 10% (95% CI: 4–18%; n = 7 studies), and 1% (95% CI: 0–5%; n = 1 studies) in South, North (West and East) and West of Iran, respectively (Additional file 2: Figure S1). The results of subgroup analysis based on diagnostic methods in human samples showed that pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes was 1% (95% CI: 0–3%; n = 3 studies), 26% (95% CI: 23–30%; n = 2 studies), and 11% (95% CI: 4–17%; n = 6 studies) based on culture, serology and PCR methods, respectively (Additional file 2: Figure S1).

The results of subgroup analysis based on geographic location in food samples showed that pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes was 7% (95% CI: 4–10%; n = 13 studies), 4% (95% CI: 2–5%; n = 11 studies), and 2% (95% CI: 1–3%; n = 4 studies), 3% (95% CI: 3–4%; n = 2 studies) in North (West and East), Central, South and all parts of Iran, respectively (Additional file 2: Figure S1).

The results of subgroup analysis based on the diagnostic methods in food samples showed that pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes was 3% (95% CI: 1–4%; n = 11 studies), 5% (95% CI: 3–6%; n = 19 studies), and 12% (95% CI: 9–14%; n = 1 studies), 2% (95% CI: 1–4%; n = 1 studies) based on culture, PCR, Real-Time PCR and culture and serology methods, respectively (Additional file 2: Figure S1).

The results of subgroup analysis based on geographic location in Animal samples showed that pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes was 9% (95% CI: 5–13%; n = 5 studies), 2% (95% CI: 0–4%; n = 2 studies), and 7% (95% CI: 3–14%; n = 1 studies) in North (West and East), Central and South of Iran, respectively (Additional file 2: Figure S1). The results of subgroup analysis based on the diagnostic methods in Animal samples showed that pooled prevalence of L. monocytogenes was 10% (95% CI: 6–13%; n = 5 studies) and 3% (95% CI: 1–5%; n = 3 studies) based on PCR and methods, respectively (Additional file 2: Figure S1).

Sensitivity analysis and meta-regression

The sample size of included studies could not be accounted as the causes of heterogeneity due to the result of carried meta-regression analysis in which no possible associated effect was observed between a sample size of included studies and pooled prevalence.

Besides, sensitivity analysis’s results concluded that none of the incorporated studies has the ability to change the overall prevalence substantially (Additional file 3: Figure S2).

Discussion

Direct transmission of L. monocytogenes from the infected animals or contaminated raw products is the main route of human cross-contamination [54]. The unique ability of this microorganism to survive food preservation or hostile environments and the presence of numerous bacterial surface components and extracellular virulence factors make L. monocytogenes as a serious threat to food safety [1, 55]. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first comprehensive systematic review of the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in foods, animal and human origin from Iran, simultaneously. Based on the meta-analysis results, the overall estimate of L. monocytogenes prevalence among human origin with 10% was slightly higher than animal and food resources, i.e. 7% and 4%, respectively. However, some reasons may explain the higher prevalence of L. monocytogenes in Iranian population compared to environmental sources. First, most of the human origin studies were performed on susceptible groups including pregnant women or hospitalized patients, so the burden of L. monocytogenes infections would be expected to be lower in the general community. Second, in two studies with the highest isolation rate, authors used the serological method for detection of L. monocytogenes among the participants [14, 44] because antigenic cross-reactivity serological methods have lower discriminatory power in epidemiological studies compared to molecular methods [56].

Due to the multifactorial nature of L. monocytogenes prevalence, its international comparison is challenging. It seems that some factors have more profound effects on the prevalence of L. monocytogenes. Regarding the role of sample type, with some variation incidence of L. monocytogenes contamination in dairy products tends to be lower than other resources such as vegetables or meat products (mostly less than 10%) [57–64]. Based on previous reports, the infection rate of domestic and wild animals is frequently higher than foods origin and has a much more variation [65–71].

Gain a global estimate of L. monocytogenes infections in human is even more challenging since most of the studies looking in the distinct range of society or samples [72–78]. Besides the variation according to the origin of isolation, various incidence rates of L. monocytogenes may arise from differences in the sample size, seasonal variability, and geographical distribution.

Listeria innocua is a ubiquitous non-pathogenic membrane of genus Listeria. This bacterium does not seem to carry the virulence-associated genes described in pathogenic species [79]. However, recently it has been shown that L. innocua can invade bovine trophoblasts, but it is unable to multiply in the intracellular environment [80]. In our findings the isolation rate of L. innocua among Iranian food resources was remarkable. To date, there is no report of human complication by this bacterium from Iran; however, two cases of L. innocua human infections were reported in European countries [79, 81]. These observations make us keep in mind that we should not rule out the potential risk of Listeria contamination rather than L. monocytogenes.

Analysis of the included studies revealed serotypes 4b, 1/2a, and 1/2b as the most prevalent serotypes. From annual trends of serotypes changes, it seems that 4b serotype is losing its dominant position and replaced by 1/2a and 1/2b. However, serotypes can be variable during different time periods, seasons or geographical distributions, and different sample type. Wang et al. showed 648 food samples collected within years 2013–2014 in Shanghai, China the majority of the isolates (more than 80%) belonged to serotypes 1/2a, and 1/2b [58]. Kevenk et al. from Turkey reported the presence of four different serotypes (1/2a, 1/2b, 1/2c, and 4b) in isolates obtained from milk and dairy products [61]. Haley et al. showed the predominance of 3 serogroups (1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b) in the isolates collected during 2004 and 2010 within a U.S. dairy herd [82]. In a study on several regions of Brazil from 1975 to 2013, with the same serotype distribution, Almeida and colleagues introduced 4b, 1/2b, and 1/2c, as the main serotypes in human and food sources [83]. Serotypes l/2a, l/2b, and 4b were the most prevalent serotypes in sows and fattening pigs in France in 2008 [70]. Hasegawa et al. showed the predominance of 1/2b, 1/2a, and 4b serotypes among black beef cattle in Japan [68]. Surveillance of invasive listeriosis within the years 2006–2010 in Italy, revealed serotypes 1/2a, 4b, and 1/2b as the frequent types [84]. When rank correlation methods show bias, the bias is likely evidence of small studies effect [85]. Meanwhile, meta-regression analysis showed that weight of studies could not be considered as a confounding factor. Also, sensitivity analysis on included studies indicated that exclusion of any study has no significant effect on the estimated pooled prevalence.

The limitations of our systematic review include the following: Firstly, due to the extent of L. monocytogenes has not yet been examined in many regions of Iran, we cannot fully represent the frequency of L. monocytogenes in the country. Secondly, the studies could not fully indicate the prevalence of L. inocua in Iran, because the prevalence of L. inocua has not yet been surveyed in many studies conducted in Iran. Third, heterogeneity was detected among the included studies therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

The results of the present study provide good epidemiological information about the contamination status and distribution of L. monocytogenes among Iranian resources. The prevalence of L. monocytogenes and prevalent serotypes in Iran is comparable with other parts of the world. Although the overall prevalence of human cross-contamination source was low, awareness about the source of contamination is very important because of a higher incidence of infections in susceptible groups.

Additional files

Study design according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. (DOC 57 kb)

Figure S1. Forest plot of pooled estimated prevalence of L. monocytogenes in subgroup analysis based on geographic location and diagnostic methods in Human (1), Food (2) and Animal samples (3). (ZIP 7589 kb)

Figure S2. Sensitivity plot of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis related to (a) Human, (b) Animal, and (c) Food. (ZIP 248 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thanks from all member of the Clinical Research Development Center of Baqiyatallah hospital. This study was financially supported in part by “Clinical Research Development Center of Baqiyatallah hospital, Tehran, Iran.

Funding

We would like to thank from the “Clinical Research Development Center of Baqiyatallah hospital” for their kindly cooperation. This study was financially supported in part by “Clinical Research Development Center of Baqiyatallah hospital”.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Authors’ contributions

RR Conceived designed and supervised the study and revised the manuscript; MH Collected and analyzed the data; RR and MH drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Reza Ranjbar, Phone: +98-21-88039883, Email: ranjbar@bmsu.ac.ir, Email: ranjbarre@gmail.com.

Mehrdad Halaji, Email: Mehrdad.md69@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Vazquez-Boland JA, Kuhn M, Berche P, Chakraborty T, Dominguez-Bernal G, Goebel W, et al. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:584–640. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.3.584-640.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fallah AA, Saei-Dehkordi SS, Rahnama M, Tahmasby H, Mahzounieh M. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Listeria species isolated from poultry products marketed in Iran. Food Control. 2012;28:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahimi E, Momtaz H, Behzadnia A, Baghbadorani ZT. Incidence of Listeria species in bovine, ovine, caprine, camel and water buffalo milk using cultural method and the PCR assay. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2014;4:50–53. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(14)60313-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalali M, Abedi D. Prevalence of Listeria species in food products in Isfahan, Iran. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;122:336–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mateus T, Silva J, Maia RL, Teixeira P. Listeriosis during pregnancy: a public health concern. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:851712. doi: 10.1155/2013/851712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3:123. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72:39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8:2–10. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sterne JA, Egger M, Smith GD. Systematic reviews in health care: investigating and dealing with publication and other biases in meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:101. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7304.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Firouzi R, Golabadi MB. Prevalence of listeria organisms in abattoir workers in Shiraz, Iran. J Appl Anim Res. 2000;17:297–300. doi: 10.1080/09712119.2000.9706315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akhondzadeh Basti A, Zahrae Salehi T, Bokaie S. Some bacterial pathogens in the intestine of cultivated silver carp and common carp. Dev Food Sci. 2004;42:447–451. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4501(04)80044-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moshtaghi H, Mohamadpour AA. Incidence of Listeria spp. in raw milk in Shahrekord, Iran. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2007;4:107–110. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2006.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahimi E, Momtaz H, Hemmatzadeh F. The prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes and campylobacter spp. on bovine car casses in Isfahan, Iran. Iran J Vet Res. 2008;9:365–370. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jamshidi M, Jahromi AS, Davoodian P, Amirian M, Zangeneh M, Jadcareh F. Seropositivity for Listeria monocytogenes in women with spontaneous abortion: a case-control study in Iran. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;48:46–48. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jami S, Jamshidi A, Khanzadi S. The presence of Listeria monocytogenes in raw milk samples in Mashhad, Iran. Iran J Vet Res. 2010;11:363–367. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahimi E, Ameri M, Momtaz H. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Listeria species isolated from milk and dairy products in Iran. Food Control. 2010;21:1448–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahmoodi MM. Occurrence of Listeria monocytogenes in raw milk and dairy products in Noorabad, Iran. J Anim Vet Adv. 2010;9:16–19. doi: 10.3923/javaa.2010.16.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lotfollahi L, Nowrouzi J, Irajian G, Masjedian F, Kazemi B, Eslamian L, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profiles of Listeria monocytogenes in spontaneous abortions in humans. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5:1990–1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahimi MK, Hashemi M, Tayebi Z, Adimi P, Masoumi M, Boroumandi S. Evaluation of indirect immunofluorescence assay for diagnosis of Listeria monocytogenes in abortion. Adv Environ Biol. 2011;5:1335–1338. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahimi E, Shakerian A, Raissy M. Prevalence of Listeria species in fresh and frozen fish and shrimp in Iran. Ann Microbiol. 2012;62:37–40. doi: 10.1007/s13213-011-0222-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safaei HG, Jalali M, Hosseini A, Narimani T, Sharifzadeh A, Raheimi E. The prevalence of bacterial contamination of table eggs from retails markets by Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes, Campylobacter jejuni and Escherichia coli in Shahrekord, Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2011;4:249-54.

- 22.Goudarzi E, Vande Yousefi J, Harzandi N. Survey of polymerase chain reaction efficiency in the detection of mycoplasma, Listeria and Brucella in culture negative samples obtained from women with abortion. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2013;23:60–69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zarei M, Maktabi S, Ghorbanpour M. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella spp. in seafood products using multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2012;9:108–112. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosseinzadeh S, Shekarforoush SS, Ansari-Lari M, EsalatPanah-Fard Jahromi M, Berizi E, Abdollahi M. Prevalence and risk factors for Listeria monocytogenes in broiler flocks in shiraz, southern Iran. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2012;9:568–572. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Safarpoor Dehkordi F, Barati S, Momtaz H, Hosseini Ahari SN, Nejat Dehkordi S. Comparison of shedding, and antibiotic resistance properties of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from milk, feces, urine, and vaginal secretion of bovine, ovine, caprine, buffalo, and camel species in Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2013;6:284-94.

- 26.Rahimi E, Momtaz H, Sharifzadeh A, Behzadnia A, Ashtari MS, Zandi Esfahani S, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of listeria species isolated from traditional dairy products in Chahar Mahal & Bakhtiyari, Iran. Bulgarian J Vet Med. 2012;15:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahimi E, Yazdi F, Farzinezhadizadeh H. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of listeria species isolated from different types of raw meat in Iran. J Food Prot. 2012;75:2223–2227. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seifi S. Prevalence and risk factors for Listeria monocytogenes contamination in Iranian broiler flocks. Acta Sci Vet. 2012:40.

- 29.Fallah AA, Saei-Dehkordi SS, Mahzounieh M. Occurrence and antibiotic resistance profiles of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from seafood products and market and processing environments in Iran. Food Control. 2013;34:630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jamali H, Radmehr B, Thong KL. Prevalence, characterisation, and antimicrobial resistance of Listeria species and Listeria monocytogenes isolates from raw milk in farm bulk tanks. Food Control. 2013;34:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jamali H, Radmehr B. Frequency, virulence genes and antimicrobial resistance of Listeria spp. isolated from bovine clinical mastitis. Vet J (London, England: 1997) 2013;198:541–542. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sohrabi R, Tajbakhsh F, Tajbakhsh E, Momeni M. Prevalence of Listeria spp in chicken, Turkey and ostrich meat from Isfahan, Iran. Glob Vet. 2013;11:80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vahedi M, Nasrolahei M, Sharif M, Mirabi AM. Bacteriological study of raw and unexpired pasteurized cow’s milk collected at the dairy farms and super markets in sari city in 2011. J Prev Med Hyg. 2013;54:120–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Momtaz H, Yadollahi S. Molecular characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from fresh seafood samples in Iran. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:149. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salehian M, Salehifar E, Esfahanizadeh M, Karimzadeh L, Rezaei R, Molanejad M. Microbial contamination in traditional ice cream and effective factors, sari 2012. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2013;23:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zarei M, Basiri N, Jamnejad A, Eskandari MH. Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. in beef, buffalo and lamb using multiplex PCR. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2013;6

- 37.Akya A, Najafi A, Moradi J, Mohebi Z, Adabagher S. Prevalence of food contamination with Listeria spp. in Kermanshah, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19:474–477. doi: 10.26719/2013.19.5.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shakib P, Ghafourian S, Goudarzi G, Ghafarzadeh M, Noruzian H. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in pregnant women in Khoram Abad, Iran. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2013;7:475–477. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eslami G, Goudarzi H, Ohadi E, Taherpour A, Pourkaveh B, Taheri S. Identification of Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors in women with abortion by polymerase chain reaction. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2014;9:e19931.

- 40.Alidoosti HA, Razzaghi Manesh MR, Mashhady Rafie SI, Dadar MO. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in dogs in Isfahan, Iran. Bulgarian J Vet Med. 2014;17:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jamali H, Radmehr B, Ismail S. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Listeria, Salmonella, and Yersinia species isolates in ducks and geese. Poult Sci. 2014;93:1023–1030. doi: 10.3382/ps.2013-03699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moosavy MH, Esmaeili S, Mostafavi E, Bagheri AF. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes from milks used for Iranian traditional cheese in Lighvan cheese factories. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2014;21:728–729. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1129923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haghi F, Zeighami H, Naderi G, Samei A, Roudashti S, Bahari S, et al. Detection of major food-borne pathogens in raw milk samples from dairy bovine and ovine herds in Iran. Small Rumin Res. 2015;131:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2015.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haghroosta A, Shakh AF, Shooshtari MM. Investigation on the seroprevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in women with spontaneous abortion. Comp Clin Path. 2015;24:153–156. doi: 10.1007/s00580-013-1876-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jamali H, Paydar M, Ismail S, Looi CY, Wong WF, Radmehr B, et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility and virulotyping of Listeria species and Listeria monocytogenes isolated from open-air fish markets. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:144. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0476-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dallal MMS, Shojaei-Zinjanab M, Rad FH. Identification and frequency of Listeria monocytogenes in vegetables and ready to eat salads of Tehran, Iran. Sci J Kurdistan Univ Med Sci. 2015;20:78–84. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mashak Z, Zabihi A, Sodagari H, Noori N, Basti AA. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in different kinds of meat in Tehran Province, Iran. Br Food J. 2015;117:109–116. doi: 10.1108/BFJ-09-2013-0268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mansouri-Najand L, Kianpour M, Sami M, Jajarmi M. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in raw milk in Kerman, Iran. Vet Res Forum. 2015;6:223–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pourkaveh B, Ahmadi M, Eslami G, Gachkar L. Factors contributes to spontaneous abortion caused by Listeria monocytogenes, in Tehran, Iran, 2015. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-Grand, France) 2016;62:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdollahzadeh E, Ojagh SM, Hosseini H, Irajian G, Ghaemi EA. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes isolated from fish, shrimp, and cooked ready-to-eat (RTE) aquatic products in Iran. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2016;73:205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pournajaf A, Rajabnia R, Sedighi M, Kassani A, Moqarabzadeh V, Lotfollahi L, et al. Prevalence, and virulence determination of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from clinical and non-clinical samples by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2016;49:624–627. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0403-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeinali T, Jamshidi A, Bassami M, Rad M. Isolation and identification of Listeria spp. in chicken carcasses marketed in northeast of Iran. Int Food Res J. 2017;24:881–887. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lotfollahi L, Chaharbalesh A, Ahangarzadeh Rezaee M, Hasani A. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility and multiplex PCR-serotyping of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from humans, foods and livestock in Iran. Microb Pathog. 2017;107:425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allerberger F, Wagner M. Listeriosis: a resurgent foodborne infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koutsoumanis KP, Kendall PA, Sofos JN. Effect of food processing-related stresses on acid tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:7514–7516. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7514-7516.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gasanov U, Hughes D, Hansbro PM. Methods for the isolation and identification of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes: a review. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:851–875. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Costard S, Espejo L, Groenendaal H, Zagmutt FJ. Outbreak-related disease burden associated with consumption of unpasteurized Cow’s milk and cheese, United States, 2009-2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23:957–964. doi: 10.3201/eid2306.151603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang W, Zhou X, Suo Y, Deng X, Cheng M, Shi C, et al. Prevalence, serotype diversity, biofilm-forming ability and eradication of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from diverse foods in Shanghai, China. Food Control. 2017;73:1068–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.10.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Osman KM, Samir A, Abo-Shama UH, Mohamed EH, Orabi A, Zolnikov T. Determination of virulence and antibiotic resistance pattern of biofilm producing Listeria species isolated from retail raw milk. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:263. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0880-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D’Amico DJ, Groves E, Donnelly CW. Low incidence of foodborne pathogens of concern in raw milk utilized for farmstead cheese production. J Food Prot. 2008;71:1580–1589. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-71.8.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kevenk TO, Terzi GG. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and serotype distribution of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from raw milk and dairy products. J Food Saf. 2016;36:11–18. doi: 10.1111/jfs.12208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dalzini E, Bernini V, Bertasi B, Daminelli P, Losio M-N, Varisco G. Survey of prevalence and seasonal variability of Listeria monocytogenes in raw cow milk from northern Italy. Food Control. 2016;60:466–470. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Garedew L, Taddese A, Biru T, Nigatu S, Kebede E, Ejo M, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of listeria species from ready-to-eat foods of animal origin in Gondar town, Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:100. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0434-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hasegawa M, Iwabuchi E, Yamamoto S, Esaki H, Kobayashi K, Ito M, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes in bovine colostrum in Japan. J Food Prot. 2013;76:248–255. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weindl L, Frank E, Ullrich U, Heurich M, Kleta S, Ellerbroek L, et al. Listeria monocytogenes in different specimens from healthy Red Deer and wild boars. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2016;13:391–397. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2015.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sarno E, Stephan R, Zweifel C. Occurrence of Erysipelothrix spp., Salmonella spp., and Listeria spp. in tonsils of healthy Swiss pigs at slaughter. Archiv fur Lebensmittelhygiene. 2012;63:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hellstrom S, Kiviniemi K, Autio T, Korkeala H. Listeria monocytogenes is common in wild birds in Helsinki region and genotypes are frequently similar with those found along the food chain. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;104:883–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hasegawa M, Iwabuchi E, Yamamoto S, Muramatsu M, Takashima I, Hirai K. Prevalence and characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes in feces of black beef cattle reared in three geographically distant areas in Japan. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2014;11:96–103. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2013.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guerini MN, Brichta-Harhay DM, Shackelford TS, Arthur TM, Bosilevac JM, Kalchayanand N, et al. Listeria prevalence and Listeria monocytogenes serovar diversity at cull cow and bull processing plants in the United States. J Food Prot. 2007;70:2578–2582. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-70.11.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boscher E, Houard E, Denis M. Prevalence and distribution of Listeria monocytogenes serotypes and pulsotypes in sows and fattening pigs in farrow-to-finish farms (France, 2008) J Food Prot. 2012;75:889–895. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Aury-Hainry K, Le Bouquin S, Labbe A, Petetin I, Chemaly M. Listeria monocytogenes contamination in French breeding and fattening Turkey flocks. J Food Prot. 2011;74:1096–1103. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-10-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tambekar DH, Dhanorkar DV, Gulhane SR, Dudhane MN. Prevalence, profile and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates from blood. J Med Sci. 2007;7:439–442. doi: 10.3923/jms.2007.439.442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gaschignard J, Levy C, Romain O, Cohen R, Bingen E, Aujard Y, et al. Neonatal bacterial meningitis: 444 cases in 7 years. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:212–217. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fab1e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bhat SA, Willayat MM, Roy SS, Bhat MA, Shah SN, Ahmed A, et al. Isolation, molecular detection and antibiogram of Listeria monocytogenes from human clinical cases and fish of Kashmir, India. Comp Clin Path. 2013;22:661–665. doi: 10.1007/s00580-012-1462-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Soni DK, Singh DV, Dubey SK. Pregnancy - associated human listeriosis: Virulence and genotypic analysis of Listeria monocytogenes from clinical samples. J Microbiol (Seoul, Korea) 2015;53:653–660. doi: 10.1007/s12275-015-5243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moon SY, Chung DR, Kim SW, Chang HH, Lee H, Jung DS, et al. Changing etiology of community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults: a nationwide multicenter study in Korea. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29:793–800. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-0929-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim NO, Jung SM, Na HY, Chung GT, Yoo CK, Seong WK, et al. Enteric Bacteria isolated from diarrheal patients in Korea in 2014. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2015;6:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang HL, Ghanem KG, Wang P, Yang S, Li TS. Listeriosis at a tertiary care hospital in Beijing, China: high prevalence of nonclustered healthcare-associated cases among adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:666–676. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Favaro M, Sarmati L, Sancesario G, Fontana C. First case of Listeria innocua meningitis in a patient on steroids and eternecept. JMM Case Rep. 2014;1. 10.1099/jmmcr.0.003103.

- 80.Rocha CE, Mol JPS, Garcia LNN, Costa LF, Santos RL, Paixão TA. Comparative experimental infection of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria ivanovii in bovine trophoblasts. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Perrin M, Bemer M, Delamare C. Fatal case of Listeria innocua bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5308–5309. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5308-5309.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haley BJ, Sonnier J, Schukken YH, Karns JS, Van Kessel JA. Diversity of Listeria monocytogenes within a U.S. dairy herd, 2004-2010. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12:844–850. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Almeida RM, Barbosa AV, Lisboa RC, Santos A, Hofer E, Vallim DC, et al. Virulence genes and genetic relationship of L. monocytogenes isolated from human and food sources in Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2017;21:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mammina C, Parisi A, Guaita A, Aleo A, Bonura C, Nastasi A, et al. Enhanced surveillance of invasive listeriosis in the Lombardy region, Italy, in the years 2006-2010 reveals major clones and an increase in serotype 1/2a. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:152. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1119–1129. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Study design according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. (DOC 57 kb)

Figure S1. Forest plot of pooled estimated prevalence of L. monocytogenes in subgroup analysis based on geographic location and diagnostic methods in Human (1), Food (2) and Animal samples (3). (ZIP 7589 kb)

Figure S2. Sensitivity plot of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis related to (a) Human, (b) Animal, and (c) Food. (ZIP 248 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.