Abstract

The up-regulation of the 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3] is well established and occurs at the transcriptional level through two vitamin D response elements in the promoter of the gene. However, the mechanism of down-regulation of the 24-hydroxylase by parathyroid hormone (PTH) has not yet been elucidated. To study the mechanism of PTH action, we used AOK-B50 cells, a porcine kidney-cell line with stably transfected opossum PTH receptor in which both the 24-hydroxylase mRNA and activity are down-regulated by PTH. Cells dosed with 1,25(OH)2D3 at 0 h, and subsequently at 0, 1, 2, or 4 h with 100 nM of PTH, showed levels of 24-hydroxylase mRNA equivalent to 72.6, 65.3, 57.2, and 37.1%, respectively, of the levels found in cells dosed with 1,25(OH)2D3 only. All cells were collected 7 h after the initial 1,25(OH)2D3 dose. This pattern of expression indicated that PTH does not act by repressing transcription but rather by making the mRNA for 24-hydroxylase susceptible to degradation. At least 1 h is required for PTH to act. Further RNA and protein syntheses are required for PTH to act. However, the sites and mechanism whereby PTH causes 24-hydroxylase mRNA degradation are unknown. Because the untranslated regions of genes can determine the stability of its transcripts, we studied the 5′ untranslated region and the 3′ untranslated region of the rat 24-hydroxylase gene by using reporter-gene strategy to identify possible PTH sites of action. None was found, suggesting that the destabilization site is elsewhere in the coding region.

Keywords: calcium metabolism‖vitamin D endocrine system

Vitamin D, as synthesized in the skin or ingested in the diet, is sequentially hydroxylated at the C25 position in the liver and at the C1α position in the kidney to form the active metabolite 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3] (1). 24-Hydroxylase is the enzyme responsible for the first step in the catabolism of 1,25(OH)2D3 that ultimately leads to the excretion of the hormone as calcitroic acid (1). The 1α-hydroxylase and the 24-hydroxylase are very tightly and reciprocally regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3 itself and parathyroid hormone (PTH) (2). 1,25(OH)2D3 activates its own breakdown by strongly inducing the 24-hydroxylase, while at the same time down-regulating the 1α-hydroxylase (1). PTH induces the 1α-hydroxylase while down-regulating the 24-hydroxylase. The induction of 24-hydroxylase mRNA by 1,25(OH)2D3 has been extensively studied and is largely due to the actions of the vitamin D receptor complexes on two vitamin D response elements in the promoter of the 24-hydroxylase gene (3, 4). The mechanism of down-regulation by PTH remains to be elucidated. It has been shown that PTH acts to decrease 24-hydroxylase mRNA, but it remains unknown whether the decrease is caused by changes in the transcription mechanism or whether it is caused by effects of PTH on mRNA stability (5). By using AOK-B50 cells, a porcine-cell line with stably transfected opossum PTH receptors (6), we have found that PTH administration diminishes stability of 24-hydroxylase mRNA.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

1,25-(OH)2D3 was purchased from Tetrionics (Madison, WI). Bovine PTH (1–34) was purchased from Peninsula Laboratories. Actinomycin D and cycloheximide were purchased from Sigma.

Cell Culture.

AOK-B50 (porcine kidney proximal tubule) cells were a generous gift from F. Richard Bringhurst (Harvard Medical School, Boston; ref. 6). Cells were maintained in DMEM (GIBCO/BRL) plus 7% (vol/vol) FBS (HyClone). When cells reached ≈80% confluency, they were dosed with ethanol or 10−8 M 1,25(OH)2D3 at 0 h and with 100 nM PTH at the indicated times after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose. Cells were collected 7 h after the ethanol or 1,25(OH)2D3 dose, unless otherwise specified.

RNA Isolation.

RNA was isolated from AOK-B50 cells with Tri reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Northern Analysis.

Total RNA (25 μg) from cells was electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gel containing 6.5% (vol/vol) formaldehyde. RNA was transferred to nylon membranes (Micron Separations, Westboro, MA) with 20× SSC (3 M NaCl/0.3 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0) by capillary action. The membranes were prehybridized and hybridized at 68°C with Quikhyb (Stratagene), according to manufacturer's instructions. The membranes were washed with 2× SSC/0.1% SDS for 20 min at 68°C, with 1× SSC/0.1% SDS for 20 min at 68°C, and finally with 0.1× SSC/0.1% SDS for 20 min at 68°C and were analyzed with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Radiolabeled porcine 24-hydroxylase cDNA (bp 1,059–1,572 of the porcine 24-hydroxylase; ref. 5) was produced by excising the cDNA fragments from the vector, purifying the insert with the GeneClean II kit (Bio 101), and labeling the purified insert by using the Prime-a-Gene labeling system from Promega and (α-32P)dCTP from Amersham Pharmacia.

Reporter-Gene Constructs.

Reporter-gene constructs containing 1,414 bp of the rat 24-hydroxylase promoter (KpnI/SmaI fragment; ref. 3) and 348 bp of 5′ untranslated region (UTR; ref. 7) in front of the luciferase gene, and 1,245 bp of 3′UTR (24prom/5UTR/3UTR) or the last 40 bp of the 3UTR (24prom/5UTR/40bp3UTR; ref. 7) following the luciferase gene were obtained by sequential insertion of these fragments into pGL3-basic (Promega). The 5′UTR and the 3′UTR were obtained by reverse-transcription (RT)-PCR amplification with Superscript II (GIBCO) and Advantage Polymerase Mix (CLONTECH) followed by cloning into pCR-BluntII-TOPO using Zero Blunt TOPO PCR cloning kit (Invitrogen). The primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and the sequences of the primers used to amplify the 5′UTR region were 5UTR forward 5′-CCAGCTCAGGGCAGAAACC-3′ and 5UTR reverse 5′-GCGACCCGTGGGACTCAGC-3′. The primers used to amplify the 3′UTR were 3UTR forward 5′-TTTTCACCCCAATCAAGACCA-3′ and 3UTR reverse 5′-TGAACCCAGGAGCCAACATAGAC-3′.

The construct containing the last 40 bp of the 3′UTR was obtained by cloning a double-stranded oligo with XbaI overhangs into the XbaI site of the plasmid following the luciferase coding region. The sequence of these oligonucleotides was 40bp3UTRF 5′-CTAGCACTACTAAACAATAAAAAATAAAATAAAGAAT-3′ and 40bp3UTRR 5′-CTAGATTCTTTATTTTATTTTTTATTGTTTAGTAGTG-3′.

All clones were sequenced on an LKB A. L. F. DNA sequencer from Amersham Pharmacia using the Thermo sequenase fluorescent-labeled primer-cycle sequencing kit (Amersham Pharmacia). Sequence analysis was performed with the WISCONSIN SEQUENCE ANALYSIS PACKAGE from the Genetics Computer Group (Madison, WI).

Transient Transfections.

AOK-B50 cells were transfected with the reporter-gene construct in six-well plates containing 50% confluent cells. Each well received 1.25 μg of DNA and 3.75 μl of lipofectin (GIBCO/BRL) in 750 μl of serum-free DMEM per well for 16 h. Plasmid-expressing β-galactosidase was cotransfected at 25 ng per 1 μg of DNA to normalize for transfection efficiency. After overnight incubation, the medium was changed to DMEM with 7% (vol/vol) FBS; the cells were dosed with ethanol or 10−8 M final of 1,25(OH)2D3 at time = 0 h and with 100 nM PTH at the indicated times after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose. After 7 h, RNA synthesis was blocked with actinomycin D (1 μg/ml), and the cells were harvested after 24 h in 1× reporter lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activity was assayed with a Monolight 2010 luminometer (Analytical Luminescence Laboratory). β-galactosidase activity was assessed by colorimetric assay using o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside as a substrate (8).

Results

PTH Diminishes the Stability of 24-Hydroxylase mRNA.

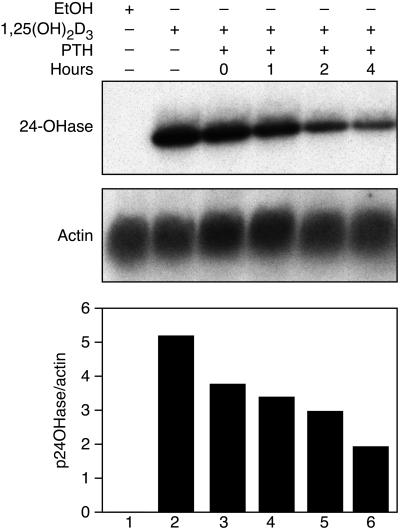

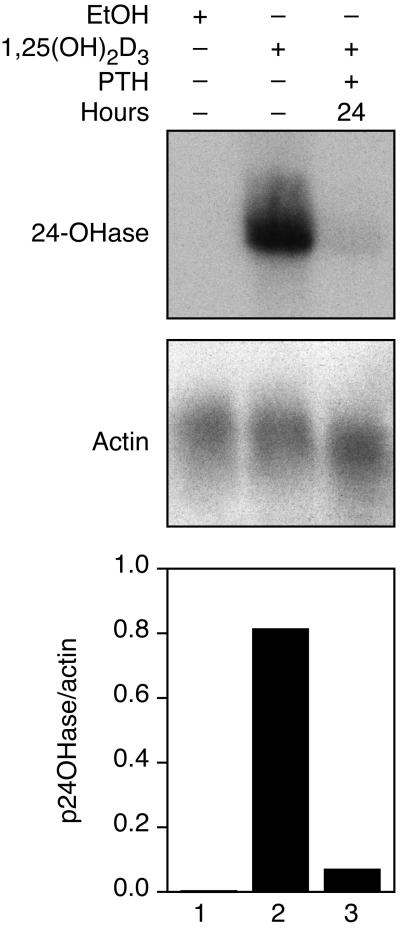

Fig. 1A shows the pattern of 24-hydroxylase mRNA expression of AOK-B50 cells that were dosed with PTH at 0, 1, 2, and 4 h after 1,25(OH)2D3 (at time = 0 h). The levels of 24-hydroxylase mRNA progressively decreased from 72.6 to 65.3, 57.2, and 37.1% when PTH was administered to the cells at time = 0, 1, 2, and 4 h, respectively. Because PTH is stable for only a few hours (9), its action on the newly synthesized mRNA is limited. If PTH were to down-regulate transcription of the 24-hydroxylase gene, the most effective block would be at the earlier time points. In Fig. 2, we show the effect of PTH on AOK-B50 cells 24 h after the addition of 1,25(OH)2D3. The amount of 24-hydroxylase mRNA accumulated in 24 h was considerable, and cells to which PTH was added had almost no 24-hydroxylase mRNA left after 3 h, indicating that PTH markedly affects the lifetime of the mRNA.

Figure 1.

AOK-B50 cells were dosed with vehicle (ethanol) or 1,25(OH)2D3 as shown at 0 h; PTH was added to the cells 0, 1, 2, or 4 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose as indicated. Cells were collected 7 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle dose. RNA was extracted, and Northern analysis was performed using 24-hydroxylase and actin as probes, as described in Materials and Methods. A representative Northern blot is shown as well as a graph representing the normalized amounts of 24-hydroxylase mRNA. The data are representative of four experiments.

Figure 2.

AOK-B50 cells were dosed with vehicle (ethanol) or 1,25(OH)2D3 as shown at 0 h; PTH was added to the cells 24 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3-dose, as indicated. Cells were collected 27 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle dose. RNA was extracted, and Northern analysis was performed with 24-hydroxylase and actin as probes, as described in Materials and Methods. A representative Northern blot is shown as well as a graph representing the normalized amounts of 24-hydroxylase mRNA. The arbitrary ratio units were based on individual PhosphorImager exposures and cannot be used to compare Northern blots from different experiments. The data are representative of two experiments.

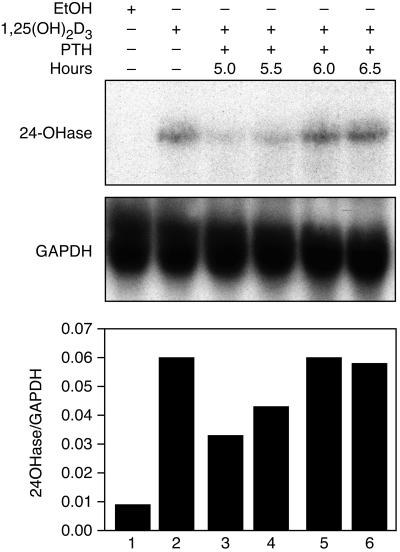

To determine the time required for PTH to act, PTH was added at 5.0, 5.5, 6.0, or 6.5 h after the addition of 1,25(OH)2D3, and the cells were collected at 7 h (Fig. 3). When PTH was added at 5.0 or 5.5 h, the level of 24-hydroxylase mRNA was 55.1 and 71.9% of the level of mRNA in cells dosed with 1,25(OH)2D3 alone. Cells dosed with PTH had no effect when provided for less than 1 h, indicating that the response requires at least 1 h to destabilize the 24-hydroxylase mRNA.

Figure 3.

AOK-B50 cells were dosed with vehicle (ethanol) or 1,25(OH)2D3 as shown at 0 h; PTH was added to the cells 5.0, 5.5, 6.0, or 6.5 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose, as indicated. Cells were collected 7 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 or vehicle dose. RNA was extracted, and Northern analysis was performed with 24-hydroxylase and GAPDH as probes, as described in Materials and Methods. A representative Northern blot is shown as well as a graph representing the normalized amounts of 24-hydroxylase mRNA. The data are representative of four experiments.

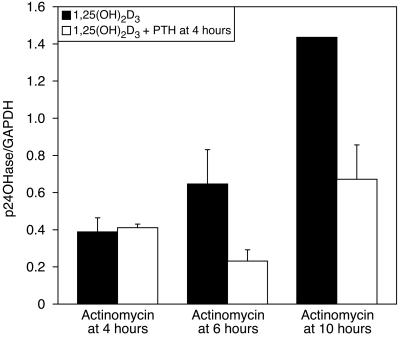

The RNA synthesis-inhibitor actinomycin D was used to determine whether RNA synthesis is required for PTH to be effective in destabilizing 24-hydroxylase mRNA (Fig. 4). AOK-B50 cells were dosed with 1,25(OH)2D3 at time = 0 h. The experimental cells were dosed with 100 nM PTH at time = 4 h, whereas the control group was not. Both groups then were dosed with actinomycin D at either 4 or 6 h. The cells were harvested after 10 h, and the RNA was analyzed by Northern blotting. Fig. 4 shows that actinomycin D given concomitantly with PTH prevents the action of PTH on mRNA. However, if PTH was allowed to act for 2 h before actinomycin D was added, cells dosed with PTH had a lower level of 24-hydroxylase mRNA, suggesting that RNA synthesis is required for the actions of PTH to occur. Cells to which actinomycin D was added at the time of harvesting (at 10 h) also showed a significant decrease in 24-hydroxylase mRNA by PTH.

Figure 4.

AOK-B50 cells were dosed with 1,25(OH)2D3 at 0 h; PTH was added to the cells 4 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose, as indicated. Actinomycin was added 4 or 6 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose, as indicated. Cells were collected 10 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose. RNA was extracted, and Northern analysis was performed with 24-hydroxylase and GAPDH as probes, as described in Materials and Methods. The graph is representative of duplicate experiments expressed as means ± SD.

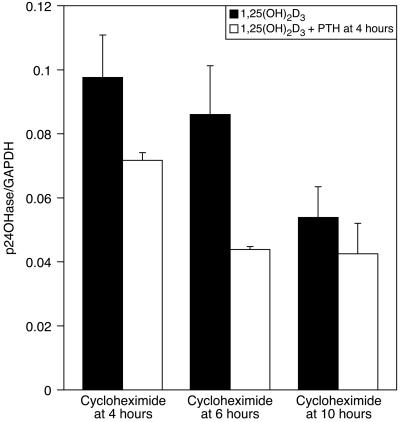

We further investigated if protein synthesis is required for the effects of PTH on 24-hydroxylase mRNA (Fig. 5). A similar experimental design was used as in Fig. 4, except that cycloheximide was added instead of actinomycin D. Fig. 5 shows the results for this experiment. Interpretation of these results is more complicated, because cycloheximide alone increases the 24-hydroxylase mRNA level, as observed (10). The levels of 24-hydroxylase mRNA in the experimental groups (dosed with PTH at 4 h) were all lower than control but were higher than the levels in the cells given cycloheximide at the time of collection (10 h). However, when cycloheximide was given together with PTH at 4 or 6 h, the levels of 24-hydroxylase mRNA were 73.5 and 50.9% of the control, respectively, indicating that protein synthesis is at least partly required for PTH to act, and yet, there is a component that decreases the levels of 24-hydroxylase mRNA in the presence of cycloheximide in response to PTH.

Figure 5.

AOK-B50 cells were dosed with 1,25(OH)2D3 at 0 h; PTH was added to the cells 4 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose, as indicated. Cycloheximide was added 4 or 6 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose, as indicated. Cells were collected 10 h after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose. RNA was extracted and Northern analysis was performed with 24-hydroxylase and GAPDH as probes, as described in Materials and Methods. The graph is representative of duplicate experiments expressed as means ± SD.

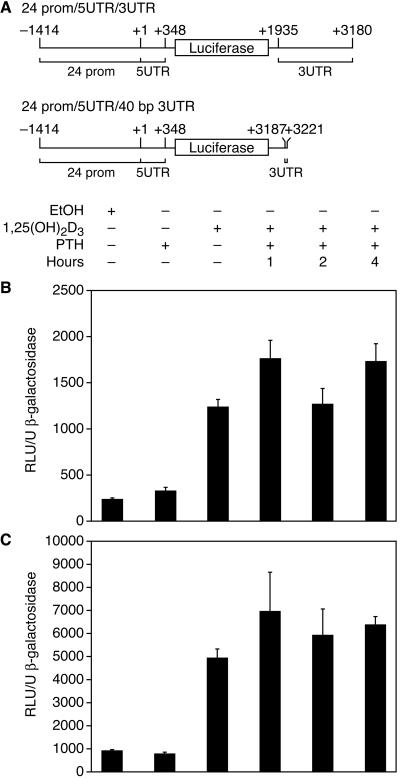

The regulation sites for mRNA stability were previously shown to occur in the UTRs of genes; thus, we made a reporter-gene construct containing a fragment of the 24-hydroxylase promoter, the 5′UTR as well as most of the 3′UTR of the rat 24-hydroxylase (24prom/5UTR/3UTR). A similar construct containing the last 40 bp of the 24-hydroxylase 3′UTR region instead of the 3UTR in the above construct also was generated (24prom/5UTR/40bp3UTR) (Fig. 6A). The 24-hydroxylase promoter region was included in both constructs to render the luciferase constructs responsive to 1,25(OH)2D3. Cells were transfected with the respective constructs and then dosed with 1,25(OH)2D3 at 0 h and with 100 nM PTH at the indicated times. mRNA synthesis was blocked after 7 h with actinomycin D, and the cells were incubated for a total of 24 h before harvest. Luciferase activity was assayed and normalized for transfection efficiency with β-galactosidase activity. The experiment was designed to allow degradation of luciferase synthesized early in the experiment so that luciferase activity could reflect the levels of luciferase mRNA at the time of actinomycin D addition.

Figure 6.

(A) 4-Hydroxylase-luciferase constructs used for transfections. Positive numbers indicate rat 24-hydroxylase cDNA bp position. Negative numbers indicate the rat 24-hydroxylase promoter fragment. (B) Luciferase activity of AOK-B50 cells transfected with the construct 24prom/5UTR/3UTR depicted in Fig. 6A. After transfection, cells were dosed with ethanol or 10−8 M final of 1,25(OH)2D3 at 0 h, and with 100 nM of PTH at the indicated times after the 1,25(OH)2D3 dose. After 7 h, RNA synthesis was blocked by using actinomycin D (1 μg/ml), and the cells were harvested after 24 h. Luciferase activity was assayed and normalized for transfection efficiency with β-galactosidase activity. (C) Luciferase activity of AOK-B50 cells transfected with the construct 24prom/5UTR/40bp3UTR depicted in Fig. 6A. The experiment was performed as described for Fig. 6B. The data are expressed as means ± SD of triplicates, representative of three experiments.

Fig. 6 B and C show the reporter-gene activity results for the constructs shown in Fig. 6A. Cells transfected with either constructs and dosed with PTH did not have lower levels of luciferase activity compared with control, indicating that both the 5′UTR and the 3′UTR of the 24-hydroxylase gene did not confer instability to the luciferase mRNA in these particular constructs in response to PTH. A Northern blot analyzing the effects of PTH on 24-hydroxylase mRNA was run in parallel to these experiments to assure that the PTH was active (data not shown). For both constructs, the activity of luciferase in the presence of PTH consistently showed greater variability than cells not dosed with PTH. The reason for the variability is not known. Control cells dosed with 1,25(OH)2D3 but not with actinomycin D to ensure that actinomycin D was active had ≈3 times the activity of cells dosed with 1,25(OH)2D3 (data not shown).

Discussion

The data presented in this paper show that PTH down-regulates 24-hydroxylase mRNA by a posttranscriptional mechanism that affects the stability of the mRNA. The succession of events in response to PTH include rapid synthesis of RNA and protein that results in a functional system 1 h after the PTH dose. It was previously described that forskolin can mimic the actions of PTH on 24-hydroxylase mRNA by increasing intracellular cAMP and through the protein kinase A pathway (5). Several reports have shown that cAMP can affect the stability of mRNA by acting on sequences in the 3′UTR of several genes, including plasminogen activator-inhibitor (11), estrogen receptor α (12), adrenergic receptor (13), and angiotensin receptor II (14), to name a few. The actions by cAMP on these genes seem to be mediated by AU-rich regions in the 3′UTR. Other reports have shown that 5′UTR also may be involved in regulating the stability mRNA (15, 16). In view of these reports, we analyzed both the 5′UTR and the 3′UTR of the rat 24-hydroxylase gene to determine whether they would render the reporter-gene luciferase mRNA more susceptible to degradation in the presence of PTH. None of the sequences tested were able to destabilize the luciferase mRNA in response to PTH.

Alignment of 3′UTR sequences for the rat, human, and porcine 24-hydroxylase showed very few sequences that are conserved among the three species and, thus, does not point to an obvious site of action of PTH, assuming that PTH acts in the same way for all species. Because the rat 3′UTR was obtained by PCR amplification, a few bases of this construct were mutated although a proofreading polymerase was used. However, an alignment of the sequences for the three species shows these mutations do not lie in any conserved regions, and thus their effect should be minimal.

It was reported that the human β1-adrenergic receptor 3′UTR can confer instability to the β-globin gene; however, the instability is no longer agonist-dependent for the chimera as it is for the wild-type gene, and, thus, the authors conclude that the 3′UTR may be necessary but not sufficient to confer agonist-mediated mRNA destabilization (17). When comparing the absolute normalized luciferase activity in Fig. 6 B and C, the activity is much lower for the construct containing most of the 3′UTR than for the construct containing only the last 40 bp of the 3′UTR. This finding may indicate that a similar phenomenon may be occurring as for the β1-adrenergic receptor, where the 3′UTR does affect the stability of the luciferase mRNA in the construct with most of the 3′UTR; the 3′UTR, although, is not sufficient to confer it in a PTH-dependent manner. Although these data may be an indication of decreased stability of this particular construct, they are not absolute proof, because other factors such as transfection efficiency and construct differences need to be considered. However, the differences in activities between the two constructs are reproducible between different experiments.

The protein coding region of c-myc has been shown to contain sequences that influence turnover of mRNA (18, 19). Thus, it is possible that the coding region may be required for the down-regulation of 24-hydroxylase mRNA by PTH. It will be interesting to address this possibility with a goal to elucidate the mechanism of action of PTH on 24-hydroxylase mRNA stability.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. F. Richard Bringhurst, M.D. (Harvard Medical School) for generously supplying us with the AOK-B50 cells, Ms. Jean Prahl for her assistance with cell culture, and Ms. Pat Mings for her help with manuscript preparation. This work was supported in part by funds from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and the National Foundation for Cancer Research.

Abbreviations

- 1,25(OH)2D3

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- UTR

untranslated region

References

- 1.Jones G, Strugnell S A, DeLuca H F. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:1193–1231. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka Y, DeLuca H F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:196–199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zierold C, Darwish H M, DeLuca H F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:900–902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohyama Y, Ozono K, Uchida M, Shinki T, Kato S, Suda T, Yamamoto O, Noshiro M, Kato Y. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10545–10550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zierold C, Reinholz G G, Mings J A, Prahl J M, DeLuca H F. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;381:323–327. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bringhurst F R, Juppner H, Guo J, Urena P, Potts J T, Jr, Kronenberg H M, Abou-Samra A B, Segre G V. Endocrinology. 1993;132:2090–2098. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.5.8386606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohyama Y, Noshiro M, Okuda K. FEBS Lett. 1991;278:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80115-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segre G V, Niall H D, Habener J F, Potts J T J. Am J Med. 1974;56:774–784. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90805-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zierold C, Mings J A, Prahl J M, Reinholz G G, DeLuca H F. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:S329. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heaton J H, Tillmann-Bogush M, Leff N S, Gelehrter T D. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14261–14268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenealy M R, Flouriot G, Sonntag-Buck V, Dandekar T, Brand H, Gannon F. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2805–2813. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.8.7613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tholanikunnel B G, Malbon C C. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11471–11478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Nickenig G, Murphy T J. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:781–787. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy N, Laflamme G, Raymond V. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5753–5762. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.21.5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dibbens J A, Miller D L, Damert A, Risau W, Vadas M A, Goodall G J. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;10:907–919. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.4.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitchusson K D, Blaxall B C, Pende A, Port J D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:357–362. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wisdom R, Lee W. Genes Dev. 1991;5:232–243. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeilding N M, Lee W M. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2698–2707. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]