Abstract

Background

Teaching practice is presumed to have significant overlap with clinical skills, yet few studies to date have assessed how residents' teaching skills influence their clinical performance.

Objective

We examined the relationship between the professional roles of residents as teachers and as practicing clinicians as well as how learning about teaching contributes to enhanced skills in the clinical realm.

Methods

Using the framework method, the authors performed a 2-phased (exploratory and confirmatory) qualitative analysis on the data sets to characterize the relationship between resident teaching and clinical skills. To investigate the relationship between teaching and clinical work, we extracted qualitative data from 300 evaluations of clinical performance for residents in a large, urban, academic internal medicine residency program submitted over a 3-year period. Informed by the preliminary framework that evolved from this analysis, we conducted a focus group of 6 residents in a dedicated clinician-educator track to examine how teaching was related to clinical work.

Results

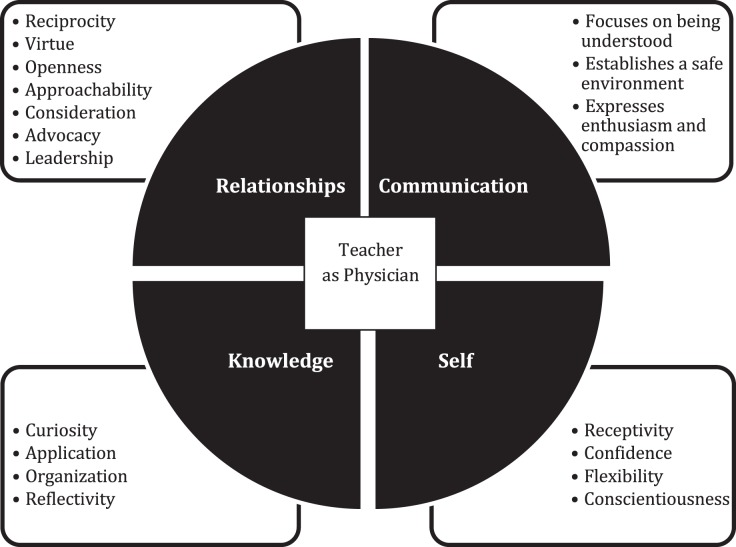

We identified attributes and skills of good resident teachers that enhance clinical skills, categorized as 18 subdomains within 4 domains: relationships, communication, relation to self, and relationship with knowledge.

Conclusions

Themes that link clinical and teaching skills are similar for both patient-physician and learner-teacher relationships. Improving residents' teaching skills may not only benefit the education of learners but also improve the care of patients.

Introduction

Residents hold essential roles as teachers and clinicians in academic medicine. Given the many parallel skills required to be both a physician and a teacher, residents who can teach effectively are more likely to be competent physicians. Few studies have investigated the relationship between resident teaching and how it affects residents' clinical skills. One study found that residents perceived as competent clinicians were also effective teachers, but it did not offer evidence as to how teaching improved clinical competence.1 Another study demonstrated a positive association between residents' level of knowledge on an in-training examination and their teaching ability, as evaluated by medical students and junior residents.2 To our knowledge, no study to date has examined the link between these 2 domains.

The purpose of our study was to examine the relationship between the professional roles of residents as teachers and as physicians as well as how learning about teaching may enhance skills in the clinical realm.

Methods

We used a 2-stage approach (exploratory and confirmatory). We searched the literature to identify attributes of physicians and clinical teachers3–7 and used narrative comments to devise a thematic framework between teaching and clinical skills. We then conducted a focus group that centered on the research question, “What are the attributes and skills of good teachers that enhance clinical skills?”

Over a 3-year study period (July 2010–June 2013) at a large, urban, academic internal medicine residency program with 191 residents, we extracted qualitative data from 300 evaluation narratives completed by faculty that included a purposeful sampling strategy to glean comments from evaluations of low, high, and typical performers.8 The evaluations were about residents' direct patient care experiences and included free text responses to open-ended questions about observed skills and attributes. As is expected of resident evaluations, comments tended to focus on the core Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competencies (eg, interpersonal and communication skills, patient care) and included comments on teaching skills.

In the exploratory phase, we used framework analysis, a structured and systematic form of thematic analysis that facilitates examination of qualitative data sets through the perspective of a priori–defined concepts and relationships, to examine the data from 300 resident evaluations. We drew on this framework to “familiarize, identify, index, chart, and interpret”9 the resident evaluation data to systematically identify and index the qualitative components. This was used to further refine the thematic framework (ie, the concepts that explained the relationship between teaching and clinical skills). Each researcher analyzed the narrative comments and identified key concepts and recurring themes. We then met as a group to compare what we had reviewed in the literature to the resident evaluation data concerning teaching and clinical care. We returned to the resident evaluation data to identify and index corresponding phrases and sections of commentary.

We defined data saturation as the point at which new data no longer introduced additional themes. We then charted text entries and comment summaries to the identified themes. Finally, we interpreted key characteristics of the charts to identify conceptual associations and typologies of the resident evaluation data. The framework after the exploratory phase included 5 major themes: (1) explicit actions with patients and learners; (2) attributes common to physicians and teachers; (3) verbal and nonverbal communication; (4) the physician-teacher's self-perspective; and (5) knowledge management by the physician-teacher.

In the confirmatory phase, we used the framework as the basis for conducting a focus group interview of 6 volunteer graduating residents from the clinician-educator track. This clinician-educator track program, which has been previously described,10 is designed for residents seeking intensive training as clinician-educators. The goal of the focus group was to confirm that we had sufficiently identified the teaching attributes and actions that contributed to residents' provision of clinical care, to determine if there were other themes that had not been captured and to further refine the framework. The discussion centered on the research question, and we prompted participants to reflect on their own experiences related to the framework's themes and how development of their teaching skills enhanced their clinical skills. Specific questions asked about how the residents treated patients in the same way they treated learners (explicit actions), which skills and traits were important for physicians and teachers (common attributes and communication), and how they perceived themselves as physician-teachers (self-perspective). Participants were also asked to describe a clinical care experience they felt was similar to teaching medical students (eg, managing knowledge).

One author (L.R.N.), who had no prior relationship with the residents, conducted the focus group, which lasted 60 minutes and was audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Identifiers and names were removed from the transcript. We independently coded the transcript according to the thematic framework and then met as a group to discuss and chart all identified themes. The resultant data echoed constructs from the evaluation data, addressing communication skills, relationships, and the nature of interactions.

This study was deemed not human subjects research by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center's Institutional Review Board.

Results

Four main themes emerged from the synthesis of the evaluation data and focus group discussion: Relationships, Communication, Relation to Self, and Relationship With Knowledge. These themes were supported by 18 subelements (Figure), with added elaboration presented in the Box.

Figure.

Conceptual Framework Linking Teaching and Clinical Skills Drawn From Resident Evaluations

Box Elements Supporting the Thematic Relationship Between Teaching and Clinical Skills.

Relationships

Reciprocity: To initiate, establish, invest, nurture, and maintain interpersonal relations or relationships through reciprocal interaction and/or cooperation of 2 or more persons.

Virtue: To demonstrate respect, civility, patience, honesty, empathy, compassion, and humility toward another individual.

Openness: To actively listen; share in decision-making; and encourage questions, debate, opinions, and contributions.

Availability: To make oneself available or approachable to others by providing or spending time, sharing knowledge, thinking aloud, and responding promptly and appropriately.

Consideration: To consider another person's perception of the safety and/or comfort of a situation or environment.

Advocacy: To assess needs and expectations in order to advocate and/or negotiate for others.

Leadership: To serve as an active role model or to lead others by example for the benefit of the community.

Communication

Focuses on being understood: To tailor communication to an audience by effectively articulating concepts; simplifying complex topics; and using nonverbal cues, active listening, and effective technology.

Establishes safe environment: To use nonjudgmental language and effective questioning skills to allow others time and space to communicate, speak, and ask questions freely. To be able to share aspects of one's self, such as life stories, successes, mistakes, and to be able to acknowledge limitations. Can also include nonverbal gestures and cues.

Enthusiasm: To be active, enthusiastic, and engaged.

Relation to Self

Receptivity: To acknowledge one's own limitations; to solicit and respond to feedback from multiple sources in a welcoming and productive manner; to be open and receptive to criticism; and to incorporate feedback.

Confidence: To be able to take risks and initiatives and to be comfortable with uncertainty.

Flexibility: To be flexible and able to adjust to new or unexpected situations or information, and to be able to identify and troubleshoot areas of concern.

Conscientious: To strive for excellence, manage time well, be dependable, be willing to admit uncertainty, and act in a professional manner.

Relationship With Knowledge

Organization: To be able to prioritize, organize, prepare, and plan, and to develop and use systems to keep up to date and be knowledgeable about one's discipline, current trends, and new research.

Application: To incorporate evidence, prior knowledge, and experience in daily practice, and to engage in critical thinking.

Curiosity: To be a self-directed and lifelong learner who is consistently inquisitive and curious and who wants to build his or her own knowledge base, and to be willing to experiment.

Reflectivity: To pause and consider all aspects of a concept or act before making a conclusion, and to identify and learn from critical incidents or meaningful events.

Relationships

Characteristics such as openness, consideration, advocacy, and a willingness to negotiate were valued in both teaching and patient care interactions. One focus group participant stated:

“All of the qualities we talk about for teaching, like creating a safe environment and listening and assessing your learners' needs . . . are all things that patients would really appreciate coming from their doctor . . .. It helps to be brilliant and smart, but it's more helpful to patients to know that you are there for them.”

Communication

The focus group noted that skills used to enhance the learner-teacher relationship were transferrable to patient-physician relationships,11 including active listening; establishing a safe environment that allows for open dialogue; sharing ideas, questions, and decisions; and expressing enthusiasm and compassion.

Relation to Self

The focus group observed that the ability to achieve one's full potential as a professional depended on skills applicable to clinical and teaching roles, including receptivity to one's own limitations, taking risks, and asking for and receiving feedback. In addition, one needed to be comfortable with uncertainty and flexible in unexpected situations.

A participant stated, “I would come back and talk to the patient to see if there was anything that didn't make sense . . .. I don't think it was something I would have done before … but I now realize that asking for feedback can actually be quite powerful on how you improve your own skills.”

Relationship With Knowledge

Some participants noted that to be a successful physician and teacher it was critical to possess a deep understanding of medicine to explain concepts in understandable terms when seeing a patient or leading a case-based discussion. Residents reported that they needed to organize and prioritize the vast amount of information presented to patients or students and to demonstrate ongoing curiosity.

Discussion

Our qualitative analysis of resident evaluation comments and a focus group of medical residents helped characterize the relationship between teaching and clinical skills and identified practices used to foster learner-teacher relationships as well as patient-physician relationships. The themes were relationships, communication, relation to self, and relationship with knowledge. These findings support the value of training physicians to be teachers and adds evidence to the scant literature that these initiatives may reap benefits in the clinical realm as well.

The competencies of interpersonal and communication skills and practice-based learning and improvement were central to residents' clinical and teaching skills. Shared decision-making, active listening, and establishing a safe environment fostered an open dialogue that promoted learner and patient relationships. Reflection and receptivity are also at the heart of teachers' and physicians' desire to improve their practice, and the parallels between the task of teaching and the task of “doctoring” may create synergy in designing programs to develop academic physicians.

This study has limitations. It was conducted at a single program, and we cannot conclude whether teaching skills transform clinical skills or the converse. Focus group participants were a highly selected cohort, and the findings may not generalize to other residents.

Further research opportunities entail examining the correlation between clinical skills and teaching skills based on these subdomains and comparing the clinical skills of residents in the clinician-educator track versus those who are not in the track.

Conclusion

The insights gained in this analysis suggest that training physicians as teachers can reinforce and extend clinical skills and may have a profound effect on their development as physicians. Improving resident teaching skills may not only benefit the education of learners but also improve the care of patients.

References

- 1.Busari JO, Scherpbier AJ. Why residents should teach: a literature review. J Postgrad Med. 2004;50(3):205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seeley AJ, Pelletier MP, Snell LS, et al. Do surgical residents rated as better teachers perform better on in-training examinations? Am J Surg. 1999;177(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatem CJ, Searle NS, Gunderman R, et al. The educational attributes and responsibilities of effective medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):474–480. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820cb28a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christmas C, Kravet S, Durso S, et al. Clinical excellence in academia: perspectives from masterful academic clinicians. Mayo Clinic Proceed. 2008;83(9):989–994. doi: 10.4065/83.9.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michels ME, Evans DE, Blok GE. What is a clinical skill? Searching for order in chaos through a modified Delphi process. Med Teach. 2012;34(8):e573–e581. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.669218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jochemsen-van der Leeuw HG, van Dijk N, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, et al. The attributes of the clinical trainer as a role model: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(1):26–34. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318276d070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalo JD, Heist BS, Duffy BL, et al. The art of bedside rounds: a multi-center qualitative study of strategies used by experienced bedside teachers. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):412–420. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2259-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Burgess R, editors. Analysing Qualitative Data. London, UK: Routledge;; 1994. pp. 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith C, McCormick I, Huang G. The clinician–educator track: training internal medicine residents as clinician–educators. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):888–891. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, et al. What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):452–466. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bee61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]