Abstract

Background

Transitions of care pose significant risks for patients with complex medical histories. There are few experiential medical education curricula targeting this important aspect of care.

Objective

We designed and tested an internal medicine transitions of care experience integrated into interns' ambulatory curriculum.

Methods

The program included 1-hour group didactics, a posthospitalization discharge visit in pairs with a home care nurse (cohort 1: 2011–2012; cohort 2: 2012–2013), and a half-day small-group visit to a skilled nursing facility led by a faculty member in geriatrics (cohort 2 only). Both visits had structured debriefings by faculty in geriatrics. For cohort 1, a quantitative follow-up survey was administered 18 to 20 months after the experience. For cohort 2, reflections were analyzed.

Results

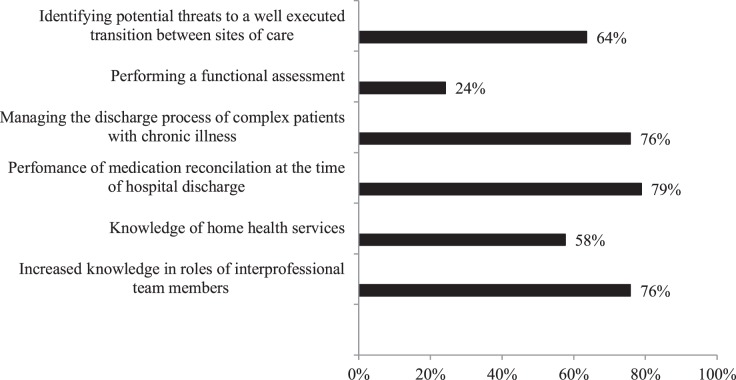

Thirty-three of 42 second-year residents (79%) in cohort 1 who participated in didactics and a home visit completed the survey. Seventy-six percent (25 of 33) reported increased knowledge of interprofessional team members' roles and the discharge process for patients with complex medical histories. Seventy-nine percent (26 of 33) reported continued use of medication reconciliation at discharge, and 64% (21 of 33) reported the experience enhanced their ability to identify threats to transitions. Of cohort 2 interns, 88% (42 of 48) participated in the home visit and 69% (33 of 48) in the skilled nursing facility visit. Intern reflections revealed insights gained, incomprehensive discharge plans, posthospital health care teams, and patients' postdischarge experience.

Conclusions

An experiential transitions of care curriculum is feasible and acceptable. Residents reported using the curriculum 18 to 20 months after exposure.

What was known and gap

Transitions of care are a critical time for patients, yet there are few curricula to enhance resident learning of this segment of care.

What is new

An experiential curriculum in posthospital care for internal medicine residents, including exposure to home care and care in a skilled nursing facility.

Limitations

Single institution and single specialty study limit generalizability; reliance on resident self-reports.

Bottom line

The transitions of care curriculum was feasible and acceptable. Residents reported using elements learned 18 to 20 months after exposure.

Introduction

Policymakers have highlighted the need to improve the quality of care and safety in hospital discharges,1–6 and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has identified transitions of care as a core competency, with milestones focusing on the ability to communicate a safe discharge plan effectively with the patient, interprofessional team, caregiver, and the next care provider.7–11

Residents are responsible for care transitions, yet feel they lack the knowledge of how to safely complete these tasks, and studies have found a need to increase resident knowledge in transitions of care.12–19 Experiential learning theory suggests that learning is best done in the context in which it occurs, and that interactions are fundamental to gain understanding.20,21

To address the need for experiential learning, we embedded an innovative curriculum in our existing postgraduate year 1 (PGY-1) ambulatory block. It provided for direct exposure to different medical environments, including home care and skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), interactions with interprofessional team members, and review of hospital discharge documentation. We hypothesized that this experiential method of learning would improve residents' skills for safe patient discharges.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

Two cohorts of PGY-1 internal medicine residents at an urban academic tertiary medical center completed the transitions of care curriculum. When this program was launched, it had no formal transitions of care curriculum.

Home Visit Curriculum

We implemented the curriculum from September 2011 through June 2013 (cohort 1; Figure 1). Core didactics were integrated into the ambulatory curriculum. Each intern participated in a 1-hour small-group didactic on “Transitions in Care” delivered by core geriatrics faculty (R.K.M.). Topics included identifying vulnerable patients, working in interprofessional teams, medication reconciliation, discharge summaries/instructions, and patient and family communication.

Figure 1.

Cohort 2 Curriculum

A pair of interns were assigned to conduct a posthospitalization discharge home visit with a home care nurse. Each nurse participated in a brief session to review teaching goals and objectives. The patients were primarily African-American, Medicare-eligible, and middle-lower socioeconomic status, with multiple chronic comorbidities and on multiple medications. The interns had not previously met the patients they were visiting due to logistical barriers to arranging visits for their patients.

Interns were expected to complete a medication reconciliation form and a transitions of care checklist, covering medication management, medical care and home services follow-up, patient and family roles, and understanding of the discharge process.22,23 A 1-hour debriefing session led by geriatrics faculty (R.K.M.) was conducted during the last didactic session of the 4-week block. Each intern pair described the patient seen in the home and key transition issues they had encountered.

SNF Curriculum

For cohort 2, which took place in 2012–2013, groups of 4 to 7 interns participated in structured, half-day visits to SNFs led by a faculty member in geriatrics or a fellow who cared for patients at that facility. The SNF visit was added to the curriculum in response to intern and faculty feedback on the value of seeing an alternative discharge site of care. The visit focused on key aspects of care transitions, including basics of SNFs, medication reconciliation, communications with staff, and discharge summaries/instructions. During the tour, interprofessional team members taught residents about their roles and discussed key elements of a successful discharge plan from hospital to SNF using examples of recent discharge summaries. Patients going to SNFs were a similar patient population to those visited in homes. The SNF staff also led a 20-minute debriefing session at the end of the visit.

This study was approved under the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection and Analysis

Survey data from cohort 1 (interns completing a home visit) were collected 18 to 20 months after completion of the transitions of care experience (at the end of PGY-2). The survey was developed by the authors without additional testing. The survey had a variety of open-ended and closed questions (provided as online supplemental material).

Cohort 2 interns were asked to complete separate reflections about the home and SNF visit. Open-ended writing allowed interns to synthesize their experiences on the home and SNF visits. The home visit reflections were discussed at the 1-hour group debriefing session on the last day of the ambulatory block. The SNF reflections were completed on site and discussed as a group. Reflections were guided by 3 questions: (1) How did this experience alter your perception of discharge? (2) How will the experience change your care for patients? (3) Were there any surprises?

Reflections were transcribed by the Mixed Methods Research Lab at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA) and entered into NVivo 10 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, VIC, Australia). We used applied thematic analysis in an iterative, 2-step process to examine the data. Applied thematic analysis is an inductive approach that allows the researcher to describe the explicit and implicit ideas that arise in the data.24 The initial broad set of codes were emergent from the data, assigned a priori, and focused on 5 themes: (1) barriers after discharge; (2) facilitators after discharge; (3) discharge instructions; (4) impact of home visits; and (5) intern expectations and surprises. Coders included a geriatrician with experience in transitions of care who led the curriculum design (R.K.M.), a third-year resident (Z.S.), and 2 qualitative research experts (S.K. and Z.S.). Coders initially applied these broad codes to each line of text. In a second phase of coding, each broad theme was subcoded into emerging categories. Subcoding proceeded in an iterative fashion as categories were created, reviewed, compared, and collapsed until no new themes emerged. Subcodes were discussed iteratively by the team as they emerged.

A subset of 16 reflections, including 8 from SNF and 8 from home visits, were double-coded for interrater reliability to ensure that all coders understood and defined the codes in the same way. A kappa statistic was calculated for each broad code across all 16 double-coded narratives. Coding discrepancies were resolved by consensus among all members of the team, resulting in a final average kappa of 0.75.

Results

Seventy-nine percent (33 of 42) of the PGY-2s in cohort 1 who participated in didactics and a home visit completed the survey. After the transitions of care experience, 76% (25 of 33) of the respondents reported increased knowledge of the role of the interprofessional team and the discharge process for patients with complex, chronic illnesses; 79% (26 of 33) reported they continued to use what they learned about medication reconciliation at hospital discharge; and 64% (21 of 33) reported an ability to identify potential threats to transitions between sites of care. Fifty-eight percent (19 of 33) indicated that the knowledge gained in home health services influenced current practice; and 24% (8 of 33) noted the experience influenced their performance of functional assessments (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cohort 1: What Aspects of Transitions of Care Experience Do You Maintain in Your Current Practice?

Of 48 residents in cohort 2, 42 (88%) participated in the home visit and 33 (69%) in the SNF visit. A total of 69 reflections were included in the analysis (6 essays were missing).

Qualitative analysis revealed 3 overarching themes: (1) the importance of completing comprehensive discharge plans and instructions; (2) awareness and admiration of posthospital health care teams; and (3) understanding the realities patients face postdischarge. The Box contains quotes for each theme and subthemes described below.

Box Cohort 2: Reflection Comments From Postdischarge Home and Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) Visit.

Importance of Completing Comprehensive Discharge Plans and Instructions

Medication Reconciliation

Given the number of medication bottles, it was understandable that Mrs. [X] originally found the task of memorizing all of her prescriptions to be daunting . . .. Going forward, I plan on not only documenting how to take each medication but also writing a quick note regarding which condition the drug is treating. –HV020

The visit highlighted the importance of reconciling medications prior to discharge and providing clear anticipatory guidance for expected medication changes . . .. It also underscored the need for comprehensive discharge summaries that succinctly describe the presentation, hospital course, and discharge condition . . . to ensure that SNFs are able to continue the intended course of care. –SNF018

Communicating More With Patients and Their Families

This experience showed me that I really have to try and make time to explain to the patient thoroughly what happened in the hospital and what we thought was going on. They may hear it every day during rounds, but I think as they leave the door, they need to hear it again . . .. This patient was aware of her follow-up appointments, and knew what medicines she was supposed to take, but had no idea why she was on those medicines, and I think that is something I can make a point to enforce during my own discharges. –HV004

I think in my future practices, I will challenge my patients to be advocates of their own health. Yes, we are providers with knowledge of their condition and medications, but [these are] their bodies and their lives and they are the ones who are ultimately responsible [. . .]. I will encourage each patient to learn his/her own medications and understand its function. I vow to do better in educating my patients on their medications, especially in the outpatient setting. I hope with this partnership patients will value the health care system as something that they're a part of instead of a foreign, nebulous organization. –HV027

Scheduling Follow-up Appointments

And if possible, all appointments should be scheduled for the patient given that the health literacy of many patients is low, and it is often more difficult for them to schedule timely appointments. –HV030

It was good to learn about the level of physician care available such that I can plan follow-up appointments appropriately. –SNF029

Awareness and Admiration for Posthospital Health Care Teams

Aptitude and Quality of Home Health Care Team

Once at home, he had frequent visits from the transition [home care] nurse. This was particularly useful because he symptomatically worsened shortly after being discharged, and the nurse was able to communicate this to his pulmonologist, who then increased [the patient's] steroid dose. The patient responded well to this; in this way, an admission was likely avoided. I was impressed by this use of various resources following discharge: the transition nurse, the pulmonologist, and the patient, all were communicating well about his changing symptoms and were able to prevent . . . a return trip to the ED. –HV013

Level of Care Provided by SNFs

I was [pleasantly] surprised by how thorough the intake and evaluation process at the SNF can be. –SNF021

I was surprised with the multidisciplinary approach to patient care available [at] the SNF. The amount of [physical therapy] the patients received each day was more than I was expecting. The social activities available to the [patient were] also unexpected but I'm sure very valuable. –SNF023

Understanding the Realities Patients Face Postdischarge

Assessing Living Situation and Social Support

Overall, this visit made me aware of the limited resources that patients have, and how important it is to consider a patient's home life upon discharge. There are many ways we can make a patient's life easier in the hospital, and many of those are available at home (OT, PT, RNs). These make it possible for us to discharge patients when they are medically ready, but we still have to make sure patients have what it takes to manage their own everyday life. That varies with the level of education, access, and help at home from family members/friends. –HV019

External factors affecting patient's lives [became] more apparent. Difficulty sleeping may often be attributed to poor sleep hygiene (attempting to sleep on the couch in the living room) . . .. Issues pertaining to mobility and physical therapy [were] also highlighted to greater extent. This particular patient, recovering from GBS, had significant difficulty with ambulation but lived on a second story apartment . . .. Without the assistance of his partner, ordinary tasks may have become impossible. –HV021

Self-Efficacy

The patient started to try using the pillbox as instructed; however, partway through declined, stating that she had her own routine to take her meds. The nurse stated as long as she had a system that worked . . . she was okay with it. Our patient was also very well informed . . .. She knew all her medication changes and the reason she was taking each one. –HV016

Our patient was one of the “good ones.” She had her discharge paperwork carefully filed in 1 sleeve of a folder. And in the other sleeve was a growing list of her daily weights . . .. She was meticulous with her record keeping. It turned out she was admitted recently for a CHF exacerbation. Her weight increased from 170 to 172 pounds, but based on her weight chart, she had fluctuated between those weights several times before without issue. –HV017

Abbreviations: HV, home visit; SNF, skilled nursing facility; ED, emergency department; OT, overtime; PT, part-time; RN, registered nurse; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; CHF, congestive heart failure.

Comprehensive Discharge Plans and Instructions

Medication Reconciliation:

Interns recognized the importance of providing detailed medication reconciliation often after witnessing patients and home care nurses refer to the discharge instructions in an effort to understand the medication regimen. Interns were struck by the number of medications patients required, and several interns vowed to make a concerted effort to finish summaries prior to discharge and to make instructions clear and simple.

Communicating More With Patients and Their Families

Interns reflected on the need to spend more time communicating with patients and their families before discharge. These reflections were usually prompted by witnessing a problem with the patient's care that the interns believed could have been avoided through better communication.

Scheduling Follow-Up Appointments

Interns identified where patients had barriers to understanding their disease and treatment, and who would benefit from early follow-up. They also discussed language and health literacy barriers to prompt follow-up.

Awareness and Admiration for Posthospital Health Care Teams

Aptitude and Quality of Home Health Care Team:

Many interns recognized the significance of interprofessional communication and home health care nurses' skills. Many praised the quality of nurses' care, patient-centered approach, and their ability to implement the discharge instructions and to work with providers to prevent rehospitalizations.

Level of Care Provided by SNFs

Most of the interns who visited SNFs were surprised at the high level of care they witnessed. Interns were impressed by the thorough intake evaluation, the interprofessional approach with physical therapy, and the support with daily living activities, and a few also mentioned they were pleasantly surprised by social activities offered at the SNF. Interns commented on the high nurse-to-patient ratio.

Understanding the Realities Patients Face Postdischarge

Those who visited patients at home appreciated the limitations of some living situations, whereas those who visited the SNF noted how staff could affect patient health outcomes.

Assessing Living Situation and Social Support

Home visits helped interns recognize how a patient's environment could create barriers to care and recovery. They described mobility problems related to clutter, carpeting, and stairs and environmental factors, such as smoke and pets. They also mentioned the impact of neighborhood safety and patients living alone without reliable social support or patients' care.

Self-Efficacy

Several interns mentioned instances in which patients' ability to take charge of their own care and understand their treatments were important keys to facilitating effective transitions posthospitalization. In many instances, the nurses helped reinforce the patient's self-efficacy.

Program Feasibility

The curriculum was embedded in the ambulatory rotation, and the half-day experiences replaced subspecialty clinics. For each year, the lead faculty (R.K.M.) spent 8 hours in didactic time (core and debriefing session). Matching the schedules of PGY-1s, home care nurses, and SNF providers required approximately 16 h/y. That time was initially supported by grant funding and, later, by the internal medicine residency. Home care nurses spent 2 to 3 hours per session with the interns and participated 3 to 4 times a year. Since the nurses were seeing patients with the interns, the time had little effect on productivity. The SNF professionals (all academic faculty or geriatrics fellows) each spent 1.5 to 2 hours and participated 2 to 3 times a year. The teaching responsibility was shared by multiple providers, and visits were scheduled in groups of 5 to 7 to minimize the number of sessions needed.

Discussion

Our transitions of care curriculum resulted in sustained intern awareness of key issues, such as medication reconciliation and importance of communication, 18 months later. The experience was positively received by residents, and the didactics, postdischarge home visit, SNF visit, and debriefing have continued for 7 years.

Our results support a recent study demonstrating that experiences with a postdischarge clinic visit, home visit, or telephone call were correlated with increased perceived responsibility for transitional care tasks.19 We provided learning experiences with patients, a variety of health care professionals, and sites of care, all directly involved in transitions of care.

This program is distinct from other effective transitions of care interventions. Published reports of educational interventions have included postdischarge visits for patients that residents had treated in the hospital and postdischarge and sites of care visits occurring during the 2- to 4-week geriatric or transitions of care rotations.17–19 Embedding the curriculum in the ambulatory schedule facilitated teaching larger groups of interns, and the block scheduling helped with scheduling home care nurses and SNF providers. Our approach did not allow interns to see patients for whom they had provided care in the hospital, but we demonstrated both the feasibility of the visits and the interns' self-reported learning of key transition issues, likely due to the strength of experiential learning with patients and health care teams.20

Establishing relationships between medical education, home care, and skilled nursing facilities can create a learning environment needed for this type of curriculum. Finding champions in local home care agencies and SNFs is important. To prevent workflow interference, coordinating the interns' schedules to align with home care nurse visit schedules is essential. By using a group of nurses as part of the teaching team, we made accommodations when needed. For the SNF clinicians, visits were scheduled in small groups to minimize the number of sessions needed.

This study has several limitations. It was conducted at a single institution, limiting generalizability. We relied on interns to self-report changes in knowledge or behavior, and positive responses could have been due to social desirability. Our survey was not tested for validity evidence, and respondents may not have interpreted items as intended.

Future research should include a review of the care plans compared with what actually happens after discharge. This could include direct observation of patient care in a postdischarge clinic and root cause analysis for readmissions. These opportunities may improve our understanding of the multifactorial issues that lead to poor transitions of care and allow continued evaluation of curricular components and effect.

Conclusion

We demonstrated that a transitions of care curriculum incorporating a posthospital home discharge visit and an SNF visit was well received and feasible. The curriculum has continued with the support of the internal medicine residency program, home care nurse agency, and health care providers of geriatric services.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of care consensus policy statement American College of Physicians–Society of General Internal Medicine–Society of Hospital Medicine–American Geriatrics Society–American College of Emergency Physicians–Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971–976. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0969-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.[MedPAC] Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Improving Incentives in the Medicare Program. Washington, DC: MedPAC; Jun, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care—a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(10):1064–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, et al. The care span: the importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(4):746–754. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of care consensus policy statement: American college of physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364–370. doi: 10.1002/jhm.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; American Board of Internal Medicine. Internal Medicine Milestone Project. 2015 Jul; https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/InternalMedicineMilestones.pdf Accessed June 29, 2018.

- 8.Lurie SJ, Mooney CJ, Lyness JM. Measurement of the general competencies of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):301–309. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181971f08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan B, Englander H, Kent K, et al. Transitioning toward competency: a resident-faculty collaborative approach to developing a transitions of care EPA in an internal medicine residency program. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):760–764. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00414.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauer KE, Soni K, Cornett P, et al. Developing entrustable professional activities as the basis for assessment of competence in an internal medicine residency: a feasibility study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1110–1114. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2372-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green ML, Aagaard EM, Caverzagie KJ, et al. Charting the road to competence: developmental milestones for internal medicine residency training. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(1):5–20. doi: 10.4300/01.01.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchanan IM, Besdine RW. A systematic review of curricular interventions teaching transitional care to physicians-in-training and physicians. Acad Med. 2011;86(5):628–639. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318212e36c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Horwitz LI, et al. “Out of sight, out of mind”: housestaff perceptions of quality-limiting factors in discharge care at teaching hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):376–381. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeCaporale-Ryan LN, Cornell A, McCann RM, et al. Hospital to home: a geriatric educational program on effective discharge planning. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2014;35(4):369–379. doi: 10.1080/02701960.2013.858332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greysen SR, Schiliro D, Curry L, et al. “Learning by doing” resident perspectives on developing competency in high-quality discharge care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1188–1194. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2094-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matter CA, Speice JA, McCann R, et al. Hospital to home: improving internal medicine residents' understanding of the needs of older persons after a hospital stay. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):793–797. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200308000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pavon JM, Pinheiro SO, Buhr GT. Resident learning across the full range of core competencies through a transitions of care curriculum. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2018;39(2):144–159. doi: 10.1080/02701960.2016.1247066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoenborn NL, Christmas C. Getting out of silos: an innovative transitional care curriculum for internal medicine residents through experiential interdisciplinary learning. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):681–685. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00316.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young E, Stickrath C, McNulty M, et al. Residents' exposure to educational experiences in facilitating hospital discharges. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(2):184–189. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00503.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yardley S, Teunissen PW, Dornan T. Experiential learning: AMEE guide No. 63. Med Teach. 2012;34(2):e102–e115. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.650741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufman DM, Mann KV. Teaching and learning in medical education: how theory can inform practice. In: Swanwick T, editor. Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons;; 2010. pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman EA. Medication discrepency tool (MDT) 2011 http://caretransitions.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/MDT.pdf Accessed June 29, 2018.

- 23.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, et al. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc;; 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.