Abstract

Background

Clinical Competency Committees (CCCs) are charged with making summative assessment decisions about residents.

Objective

We explored how review processes CCC members utilize influence their decisions regarding residents' milestone levels and supervisory roles.

Methods

We conducted a multisite longitudinal prospective observational cohort study at 14 pediatrics residency programs during academic year 2015–2016. Individual CCC members biannually reported characteristics of their review process and Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestone levels and recommended supervisory role categorizations assigned to residents. Relationships among characteristics of CCC member reviews, mean milestone levels, and supervisory role categorizations were analyzed using mixed-effects linear regression, reported as mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and Bayesian mixed-effects ordinal regression, reported as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% credible intervals (CrIs).

Results

A total of 155 CCC members participated. Members who provided milestones or other professional development feedback after CCC meetings assigned significantly lower mean milestone levels (mean 1.4 points; CI –2.2 to –0.6; P < .001) and were significantly less likely to recommend supervisory responsibility in any setting (OR = 0.23, CrI 0.05–0.83) compared with CCC members who did not. Members recommended less supervisory responsibility when they reviewed more residents (OR = 0.96, 95% CrI 0.94–0.99) and participated in more review cycles (OR = 0.22, 95% CrI 0.07–0.63).

Conclusions

This study explored the association between characteristics of individual CCC member reviews and their summative assessment decisions about residents. Further study is needed to gain deeper understanding of factors influencing CCC members' summative assessment decisions.

What was known and gap

Clinical Competency Committees (CCCs) are critical to the success of milestone-based assessment, yet little is known about how members' review processes influence assessment decisions.

What is new

A prospective cohort study in multiple pediatrics programs assessed CCC members' processes and milestone and supervisory ratings.

Limitations

Single-specialty study; reliance on self-reporting.

Bottom line

Providing milestone-based feedback after CCC meetings was associated with lower milestone levels and lower likelihood of recommending supervisory responsibility. Further study of these associations is needed.

Introduction

With the advent of milestone-based assessment, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has required programs to convene Clinical Competency Committees (CCCs).1 The literature on CCCs to date has largely focused on how-to approaches for designing a CCC2–5 and potential best practices for the CCC review process.6–15

While studies have not yet closely examined the work performed by CCCs, 2 aspects of their efforts stand out. First, CCCs focus on making summative assessments in many cases without direct observation of residents in the clinical environment.1,2,16 In contrast, much of the milestone and entrustment literature has focused on frontline assessors.17–23 Second, while milestones and CCCs could represent a new framework for planned, vetted reviews of resident performance, recent discussions suggest that in actuality, milestones may serve as the impetus to create a more intentionally designed program of resident assessment.24 Yet, relatively little is known about the summative assessment work of CCCs. We conducted a multi-institutional study to explore associations between characteristics of individual CCC member reviews and the summative assessment decisions they make about resident physicians, namely ACGME milestone levels and recommended supervisory role categorizations (ie, whether or not residents may serve in supervisory capacities and in what settings).

Methods

Setting and Participants

This longitudinal prospective observational cohort study was conducted during the 2015–2016 academic year. Fourteen pediatrics residency programs in the Association of Pediatric Program Directors (APPD) Longitudinal Educational Assessment Research Network (LEARN) participated (participant information provided as online supplemental material). Programs were chosen for their representative range of size, program type, and geographic location. Geographic location was due to the possibility of regional differences in how groups of programs may approach several aspects of residency education.

Eligible study subjects at each program included current CCC members, all categorical pediatrics residents, and program directors. For feasibility purposes, programs were given the option to report data for all pediatrics residents or a defined subset of residents whose performance spanned the full range of performance.

Intervention

Data collection occurred during biannual CCC reviews and milestone reporting periods of the academic year (winter 2015 and spring 2016), with data submitted to the research network between December 2015 and August 2016. Site leads were asked to recruit individual CCC members at their program via e-mail. These participants provided details about their review processes through an electronic survey (provided as online supplemental material).

Outcomes

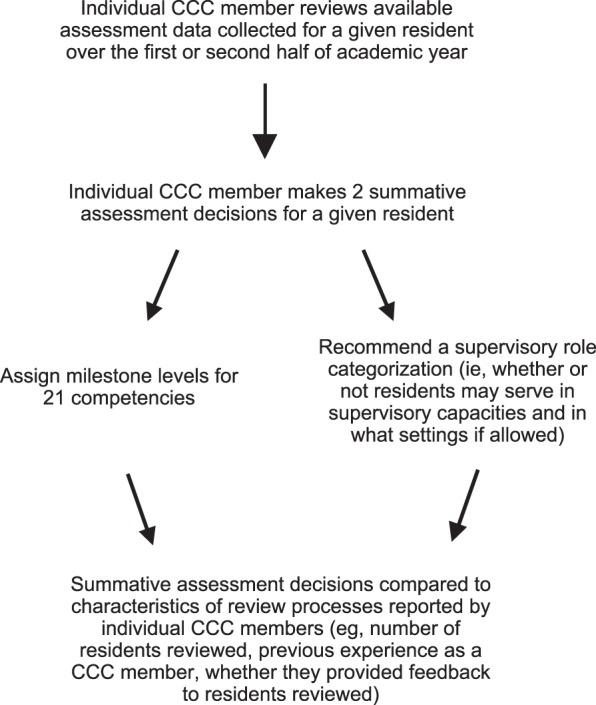

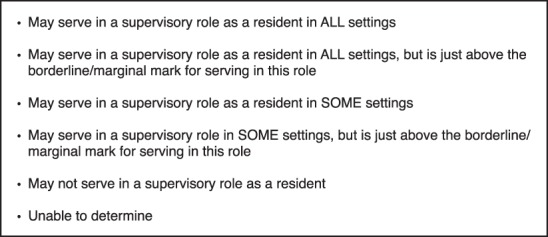

During each review cycle, individual CCC members were asked to provide 2 study variables for the residents reviewed (Figure 1): ACGME milestone levels (1–5 scale, by 0.5 increments) selected for the 21 ACGME reporting competencies and their recommended supervisory role categorization, choosing from 5 categories (no settings to all settings), including inpatient and outpatient general pediatrics and intensive care (Figure 2). This entrustment inference (“readiness to supervise others”) is 1 of several defined by the Pediatrics Milestones Assessment Collaborative (an effort of APPD LEARN, the American Board of Pediatrics, and the National Board of Medical Examiners). It embraces a broader view of entrustment22,23,25 than focusing on individual specific entrustable professional activities to determine the level of entrustment germane to the specialty.26–29

Figure 1.

Study Data Collection Process

Figure 2.

Supervision Categories

One program did not have a review process where CCC members were assigned residents, and the program director reported the consensus decisions of the group. Program directors also provided information about how many CCC members prereview residents prior to full CCC meetings. Study questions were developed, reviewed, and edited by a group of 12 residency and medical education research leaders through an iterative process without field testing.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center (lead site) granted exempt status to this study, and at each participating program, the IRB reviewed and either approved or exempted the study.

Analysis

Frequencies and descriptive statistics (mean, range, interquartile range) for the self-reported CCC member review characteristics were calculated using R version 3.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).30 The ACGME milestone levels were averaged across the 21 competencies for each resident to construct a mean milestone level, called a summative milestone profile (ranging from 1 to 5). Our goal in developing this summative profile was to aggregate milestone ratings into a single summative assessment for the purpose of comparison. For 3 pediatrics milestones, levels are intended to range from 1 to 4, but because many programs submitted at least 1 level of 4.5 or 5 on 1 competency, we did not transform levels on these competencies before averaging them. A sensitivity analysis that excluded these competencies from the summative milestone profile did not show a change in the results.

We examined the relationship between characteristics of individual CCC member reviews and the summative milestone profile by fitting a set of linear mixed models to mean milestone levels with resident year, with each review characteristic variable as a fixed-effect predictor, and random effects for resident, program, and CCC member, using the lme4 and lmerTest packages.31,32 We used histograms of the residuals to visually confirm roughly normal distributions of error in the mixed models, and report both unadjusted P values and P values adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sîdak procedure.33 We entered characteristics with univariate regression coefficients significant at P < .02 into a single multivariate linear mixed model, along with resident year and random effects.

We also examined the relationship between characteristics of individual CCC member reviews and recommended supervisory role categorizations, excluding 8 reports of “unable to determine.” We collapsed the supervisory role categorizations into 3 categories: “may not serve,” “may serve in some settings,” and “may serve in all settings.” This was done to simplify the results for easier understanding. We then fit a set of mixed-model ordinal (continuation ratio) regressions to the supervisory role categorization, with resident year as a fixed nominal effect predictor, each single review characteristic variable as fixed, category-specific, nominal effect predictor, and random effects for resident, program, and CCC member, using full Bayesian inference with an uninformative prior and multi-chain Monte Carlo sampling to provide unbiased estimates and credible intervals via the Stan system34 and the brms R package.35

In analyses of the relationship between types of information reviewed and summative assessment decisions, we only analyzed options reported by the majority of CCC participants because 31 of 35 types of information reviewed were reported only by a small number of participants. We report effect sizes and 95% confidence or credible intervals for each review characteristic predictor.

Results

Across the 14 sites, 155 of 192 CCC members and all 14 program directors participated in this study. Over 2 review cycles (midpoint and end of academic year), participants reported milestone assignments and supervisory role categorizations for 463 of 852 residents at the study sites (307 both cycles; 34 fall only; 122 spring only). Supervisory role categorizations were distributed as follows: able to supervise in all settings (level 5, n = 512), all settings but borderline (level 4, n = 56), some settings (level 3, n = 47), some settings but borderline (level 2, n = 80), not able to serve as a supervisor (level 1, n = 67), and unable to assign a level (n = 8).

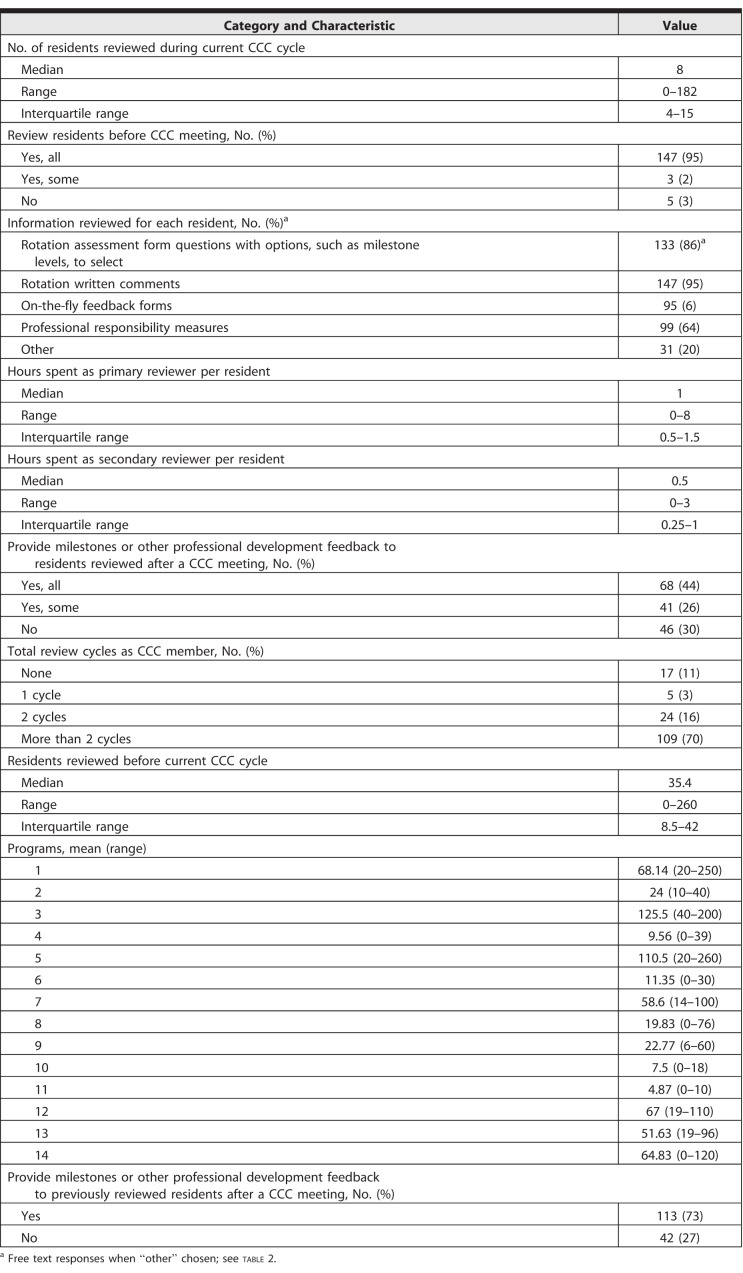

Individual CCC members reviewed a median of 8 residents per cycle (interquartile range [IQR] 4–15, Table 1). Most members (97%, 150 of 155) indicated that they reviewed residents before CCC meetings. Based on program director reports, residents were reviewed by 1 CCC member before a full CCC meeting at 8 programs. Three of the programs had additional members review select residents with identified concerns before or during the primary review. The remaining 6 programs had 2 or more CCC members prereview all residents prior to a full CCC meeting. When serving as the primary reviewer assigned to residents, individual CCC members spent a median of 1 hour (range 0–8, IQR 0.5–1.5) reviewing a resident and a median of 0.5 hours (range 0–3, IQR 0.25–1) when serving as a secondary reviewer. As Table 1 and the Box show, individual CCC members reviewed a variety of assessment data types, predominated by written comments (eg, narrative assessment data) in end-of-rotation assessments (95%, 147 of 155). Most CCC members provided milestones or other professional development feedback to all (44%, 68 of 155) or some (26%, 41 of 155) of the residents reviewed. Finally, most CCC members (70%, 109 of 155) had been part of more than 2 CCC review cycles.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) Member Reviews

Box Other Information Reviewed by Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) Members (No. of Responses).

In-training examination score (10)

Individualized learning plan (10)

360s (7)

Procedure logs (5)

Self-assessment (5)

Nursing evaluations and comments (5)

Quality improvement project (4)

Critical incidents (3)

Conference attendance (2)

Academic plan (2)

Continuity clinic performance (2)

Student evaluation (2)

Scholarly work (1)

PREP (a board review resource) progress (1)

Do not personally review residents (1)

Progress on track project (1)

Direct observations (1)

Senior talk (1)

Discussion with chiefs/other educators (1)

Scholarly works (1)

Comments program director receives (1)

Credentials (1)

Verbal feedback (1)

Peer evaluations (1)

Milestone summary form (1)

Parent/patient evaluations (1)

Teaching documentation (1)

Prior CCC meeting information (1)

Extra meetings or issues for resident (1)

Structured clinical observations translated to milestones plus written comments (1)

Feedback from other clinicians (face to face) if I don't have an excellent handle of the resident's milestones (1)

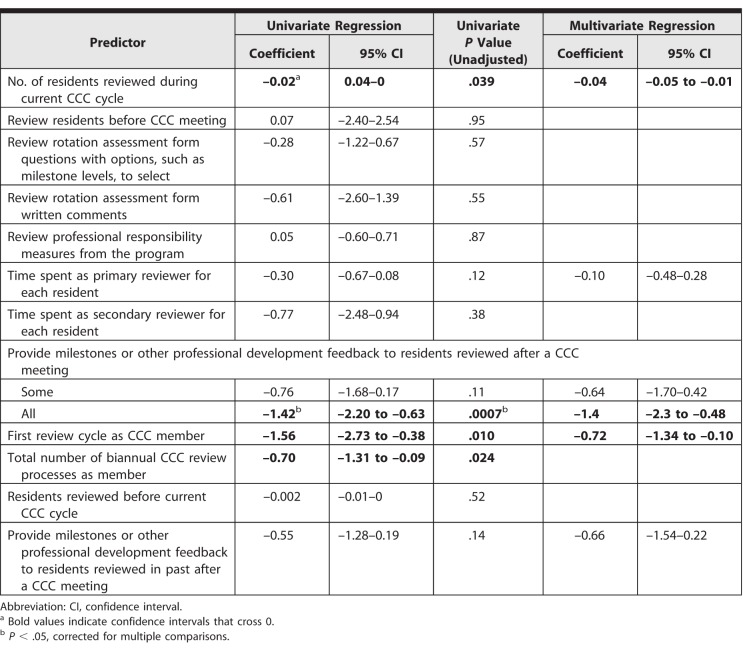

Association Between Characteristics of CCC Member Reviews and Summative Milestone Profiles

After adjusting for multiple comparisons and controlling for resident year and resident clustering in CCC member, program, and review cycle, CCC members assigned lower summative milestone profiles when they provided post-CCC meeting milestones or other professional development feedback to all reviewed residents, compared with members who did not provide such feedback (regression coefficient –0.55; 95% CI 1.28–0.19; Table 2), along with other significant predictors. These CCC members assigned an average milestone level 1.4 levels lower than faculty who did not provide such feedback. We left the characteristic “first CCC review cycle” out of the multivariate model as it was linearly dependent with the “total number of CCC review cycles” predictor, which we retained. In the multivariate model, all significant univariate predictors remained significant and had similar coefficients (Table 2, right column).

Table 2.

Association Between Characteristics of Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) Member Reviews and Summative Milestones Profile

Association Between Characteristics of CCC Member Reviews and Recommended Supervisory Role Categorizations

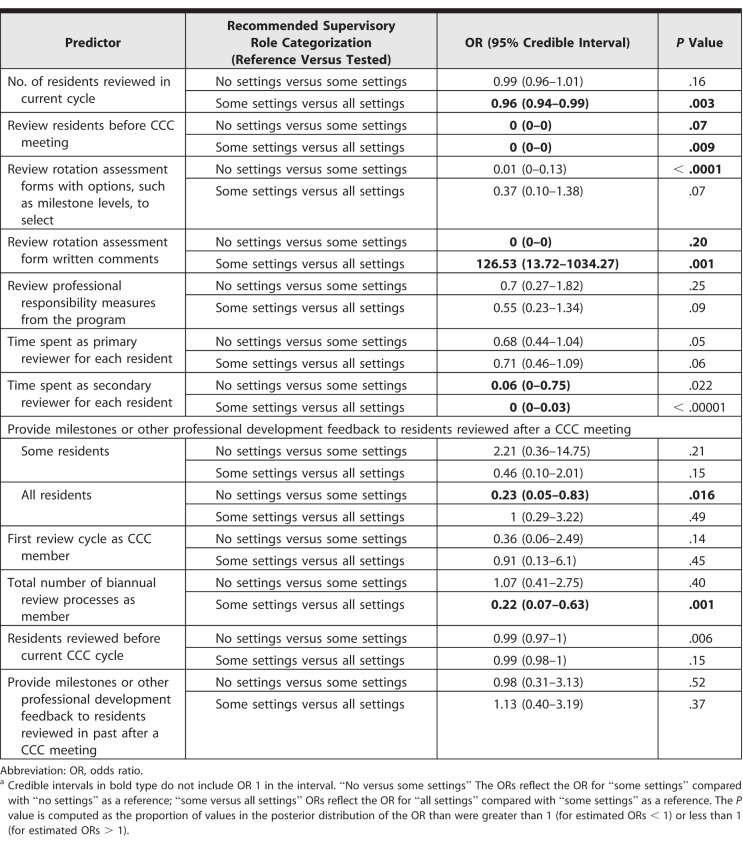

Reviewing more residents during the current review cycle was associated with individual CCC members being significantly more likely to place residents in the “some settings” category compared with “all settings” (odds ratio [OR] = 0.96; 95% credible interval [CrI] 0.94–0.99; Table 3).

Table 3.

Association Between Characteristics of Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) Member Reviews and Recommended Supervisory Role Categorizationa

Completing reviews of residents prior to the full CCC meeting was significantly associated with individual members recommending residents in categories allowing for less supervisory responsibility, with both “no settings” being more likely than “some settings” and “some settings” being more likely than “all settings.”

When reviewers provided post-CCC meeting milestones or other professional development feedback to all residents reviewed, they were more likely to place them in the “no settings” rather than “some settings” category (OR = 0.23, 95% CrI 0.05–0.83).

Finally, being involved in more biannual CCC processes in the past was associated with being more likely to place a resident in the “some settings” category compared with “all settings” (OR = 0.22, 95% CrI 0.07–0.63).

Discussion

In this study, we found that individual CCC members who provide milestones or other professional development feedback to residents assigned lower milestone levels and recommended less supervisory role responsibility. In addition, reviewing more residents during a given cycle, being involved in more biannual CCC cycles, and completing reviews of residents prior to full CCC meetings were all associated with CCC members recommending residents be granted less supervisory responsibility.

This study suggests that individuals' experience and attributes of their review process influence the summative assessment decisions they make as members of the CCC, including that reviewing more residents may lead individual CCC members to be more stringent in assigning summative assessment decisions. This raises the question of whether they are more discerning based on their vantage point of reviewing a larger number of composites of residents' performance, or whether they may satisfice judgments due to time pressures or other factors. The CCC members completing their first cycle also assigned lower milestone ratings. Explanations may exist for these seemingly contradictory findings, such as CCC members being more cautious when completing their first cycle, and thus more likely to assign lower milestones.

Individual CCC members who completed resident reviews prior to full CCC meetings were similarly more stringent when recommending supervisory roles. This finding highlights the importance of further study of CCC member decisions made before, compared with during, full CCC meetings. Future efforts should seek to elucidate the role and value of individual CCC member review versus group-level decisions, including potential sources of bias.2,36

Stringency in milestone ratings and supervisory roles was also observed when individual CCC members provided milestone or other professional development feedback to all residents they reviewed. This finding warrants further study to determine if providing performance feedback develops relationships with residents that allow for more honest and accurate summative assessment, whether providing such feedback happens more frequently with lower-performing residents, or if other explanations exist.

This study has limitations. We did not gather data on faculty training relevant to assessment. We did not test our survey questions for validity evidence, and respondents may not have interpreted questions as intended. Data were reported by individual CCC members without objective measures of assessment programs or review processes, and we did not include an objective measure of resident performance for comparison to the summative milestone profiles and supervisory role categorizations. This study was conducted in 1 specialty, and its results may not generalize. Finally, we considered only the role that review characteristics of CCC members played in their summative assessment decisions.

Conclusion

This study found that individual CCC members who reviewed more residents during a given CCC review cycle were involved in more biannual CCC review cycles, completed reviews of residents prior to full CCC meetings with all or most CCC members present, and provided milestones or other professional development feedback to residents assigned lower summative milestone ratings and supervisory roles to residents.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chahine S, Cristancho S, Padgett J, et al. How do small groups make decisions? A theoretical framework to inform the implementation and study of clinical competency committees. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6(3):192–198. doi: 10.1007/s40037-017-0357-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Promes SB, Wagner MJ. Starting a clinical competency committee. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1):163–164. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00444.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French JC, Dannefer EF, Colbert CY. A systematic approach toward building a fully operational clinical competency committee. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e22–e27. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauer KE, Kohlwes J, Cornett P, et al. Identifying entrustable professional activities in internal medicine training. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):54–59. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00060.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross FJ, Metro DG, Beaman ST, et al. A first look at the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education anesthesiology milestones: implementation of self-evaluation in a large residency program. J Clin Anesth. 2016;32:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sklansky DJ, Frohna JG, Schumacher DJ. Learner-driven synthesis of assessment data: engaging and motivating residents in their milestone-based assessments. Med Sci Educator. 2017;27(2):417–421. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ketteler ER, Auyang ED, Beard KE, et al. Competency champions in the clinical competency committee: a successful strategy to implement milestone evaluations and competency coaching. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(1):36–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shumway NM, Dacus JJ, Lathrop KI, et al. Use of milestones and development of entrustable professional activities in 2 hematology/oncology training programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):101–104. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00283.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong R. Observations: we need to stop drowning—a proposal for change in the evaluation process and the role of the clinical competency committee. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):496–497. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00131.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mount CA, Short PA, Mount GR, et al. An end-of-year oral examination for internal medicine residents: an assessment tool for the clinical competency committee. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):551–554. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00365.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donato AA, Alweis R, Wenderoth S. Design of a clinical competency committee to maximize formative feedback. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2016;6(6):33533. doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v6.33533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schumacher DJ, Sectish TC, Vinci RJ. Optimizing clinical competency committee work through taking advantage of overlap across milestones. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(5):436–438. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johna S, Woodward B. Navigating the next accreditation system: a dashboard for the milestones. Perm J. 2015;19(4):61–63. doi: 10.7812/TPP/15-041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman KA, Raimo J, Spielmann K, et al. Resident dashboards: helping your clinical competency committee visualize trainees' key performance indicators. Med Educ Online. 2016;21(1):29838. doi: 10.3402/meo.v21.29838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lomis K, Amiel JM, Ryan MS, et al. Implementing an entrustable professional activities framework in undergraduate medical education: early lessons from the AAMC Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency Pilot. Acad Med. 2017;92(6):765–770. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterkenburg A, Barach P, Kalkman C, et al. When do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1408–1417. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab0ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choo KJ, Arora VM, Barach P, et al. How do supervising physicians decide to entrust residents with unsupervised tasks? A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):169–175. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy TJT, Rehehr G, Baker GR, et al. Point-of-care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med. 2008;83(suppl 10):89–92. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauer KE, ten Cate O, Boscardin C, et al. Understanding trust as an essential element of trainee supervision and learning in the workplace. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2014;19(3):435–456. doi: 10.1007/s10459-013-9474-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheu L, Kogan JR, Hauer KE. How supervisor experience influences trust, supervision, and trainee learning: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2017;92(9):1320–1327. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hicks PJ, Margolis M, Poynter SE, et al. The Pediatrics Milestones Assessment Pilot: development of workplace-based assessment content, instruments, and processes. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):701–709. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner TL, Bhavaraju VL, Luciw-Dubas UA, et al. Assessment of pediatric interns and sub-interns on a subset of pediatrics milestones. Acad Med. 2017;92(6):809–819. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmboe ES, Call S, Ficalora RD. Milestones and competency-based medical education in internal medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1601–1602. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hicks PJ, Schwartz A. The Philip Dodds Memorial Lecture. MedBiquitous Annual Conference; Baltimore, MD: 2017. The story of PMAC: a workplace-based assessment system for the real world. Paper presented at. June 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 2007;82(6):542–547. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31805559c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ten Cate O, Snell L, Carraccio C. Medical competence: the interplay between individual ability and the health care environment. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):669–675. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.500897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen HC, van den Broek WES, ten Cate O. The case for use of entrustable professional activities in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):431–436. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rekman J, Hamstra SJ, Dudek N, et al. A new instrument for assessing resident competence in surgical clinic: the Ottawa clinic assessment tool. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(4):575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2016 https://www.R-project.org Accessed June 26, 2018.

- 31.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, et al. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 2.0-32. 2016.

- 33.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carpenter B, Gelman A, Hoffman MD, et al Stan: a probabilistic programming language. J Stat Softw. 2017;76(1):1–32. doi: 10.18637/jss.v076.i01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bürkner PC. brms: an R Package for Bayesian Multilevel Models using Stan. J Stat Softw. 2017;80(1):1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauer KE, Chesluk B, Iobst W, et al. Reviewing residents' competence: a qualitative study of the role of clinical competency committees in performance assessment. Acad Med. 2015;90(8):1084–1092. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.