Abstract

Background

a trend towards decline in disability has been reported in older adults, but less is known about corresponding temporal trends in measured physical functions.

Objective

to verify these trends during 2001–16 in an older Swedish population.

Methods

functional status was assessed at three occasions: 2001–04 (n = 2,266), 2007–10 (n = 2,033) and 2013–16 (n = 1,476), using objectively measured balance, chair stands and walking speed. Point prevalence was calculated and trajectories of change in impairment/vital status were assessed and were sex-adjusted and age-stratified: 66; 72; 78; 81 and 84; 87 and 90.

Results

point prevalence of impairment was significantly lower at the 2013–16 assessment than the 2001–04 in chair stand amongst age cohorts 78–90 years, and in walking speed amongst age cohorts 72–84 years (P < 0.05), but not significantly different for balance. The prevalence remained stable between 2001–04 and 2007–10, while the decrease in chair stands and walking speed primarily occurred between 2007–10 and 2013–16. Among persons unimpaired in 2007–10, the proportion of persons who remained unimpaired in 2013–16 tended to be higher, and both the proportion of persons who became impaired and the proportion of persons who died within 6 years tended to be lower, relative to corresponding proportions for persons unimpaired in 2001–04. Overall, there were no corresponding changes for those starting with impairment.

Conclusions

our results suggest a trend towards less functional impairment in older adults in recent years. The improvements appear to be driven by improved prognosis amongst those without impairments rather than substantial changes in prognosis for those with impairments.

Keywords: walking speed, gait speed, chair stands, balance, physical performance, older people

Introduction

Despite the rapid gain in life expectancy in the last century, it is not clear to what extent the added years consist of healthy years or years lived in poor health and disability [1]. We recently reported stable or even declining levels of disability, defined as the inability to perform basic activities of daily living (ADL) independently [2]. Consistent findings were also reported in Sweden [3, 4], in the Netherlands [5] and in Denmark [6]. However, there is also inconsistency during the last two decades, especially concerning light disability, such as mobility problems [1, 7–9]. For example, results from the US National Health Interview Survey showed an increase in the prevalence of mobility problems among people aged 65 years and older from 1998 to 2006 [9]. Disability is a construct based on physical functioning of individuals within their environments [10], therefore, disability trends can be influenced by changes in the environment such as development of technical equipment [3]. Thus, it is not clear to what extent the encouraging trend towards declines in disability in the older population reflects actual improvements in physical function.

Few recent studies have examined temporal trends in objective measures of physical function, such as balance, walking speed and chair stands. One existing study examined physical function in two cohorts of Danish nonagenarians, born 10 years apart and suggested an increasing trend in chair stand limitations and in the proportion of people being unable to walk [6]. In contrast, other studies have reported stable levels, improvements in physical function [11–13] or even a prominent reduction in mobility limitations over time (1968–92) [14, 15]. A Swedish study of temporal trends in walking limitations from 1968 to 2002 found steady levels for most age groups, but a decreasing trend for those aged 55–76 from 1981 to 2001 [16].

In this study, we aim to verify the temporal trends in objectively measured physical function during 2001–16 in a population of Swedes aged 66–90 years. As measures of physical function are strong markers of current health status and independent predictors of disability, dementia, healthcare utilisation and mortality in older adults [17–19], studying their temporal trends have relevant clincial and public health implications [19].

Methods

Data were gathered from a longitudinal study carried out in the Kungsholmen district of Stockholm, Sweden, from 2001 to present: the Swedish National study of Aging and Care in Kungsholmen (SNAC-K). All phases of SNAC-K have been approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Study population

The study population was derived from three assessments in SNAC-K (2001–04, 2007–10 and 2013–16). SNAC-K (http://www.snac-k.se) [20] targeted individuals aged 60+ living either at home or in institutions in Kungsholmen. The sample was randomly selected by specific age cohorts (60, 66, 72, 78, 81, 84, 87, 90, 93, 96 and 99+ years), and reassessed at different intervals: 6-year intervals in the younger age groups (60–72 years old) and 3-year intervals in the older groups (78+ years old). There were 4,590 persons who were eligible at baseline, of which 3,363 (73.3%) participated at the baseline assessment. A new cohort of 81 year olds was added at the SNAC-K 2007–10 assessment, in which 282 persons were eligible, of whom 194 (68.8%) participated; a further new cohort of 81 year olds was added at the SNAC-K 2013–16 assessment, in which 340 persons were eligible, of whom 195 (57.4%) participated.

The samples of the present study at each assessment were constructed to maximise comparability in age resulting in five categories: 66; 72; 78; 81 and 84; and 87 and 90 years. There was no age 66 cohort examined during the 2013–16 study period. Since the time between each of the three assessments in the present study was 6 years, all participants transitioned to the next age group from one phase to another, i.e. people aged 66 years in 2001–04 were 72 years in 2007–10, etc. Since all analyses were age-stratified (please see Statistical methods), there were no people who participated in two or more waves and they were in the same analyses. The size of the study population for each assessment, the transition between phases and number of deaths and dropouts are reported in Figure 1 in the Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online.

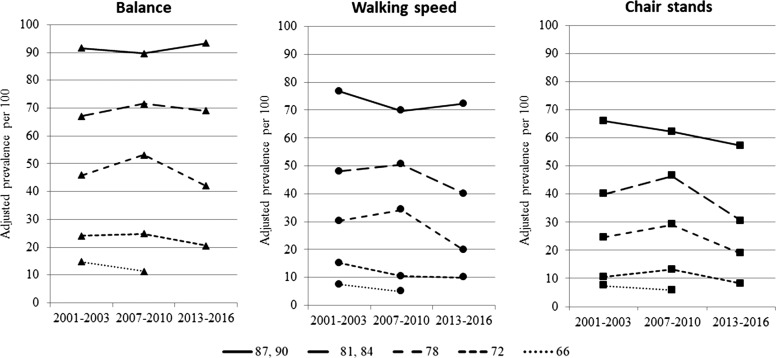

Figure 1.

Sex-adjusted point prevalence (per 100) of impairment in physical function at each of the three assessments among SNAC-K participants during the period 2001–16, stratified by age.

Performance measures of physical function

The assessment of physical function was based on three performance measures of balance, chair stands and walking speed. The measure of balance was based on how long the person was able to stand on one leg (up to 60 s) with eyes open [21]. Each leg was tested twice, and the best overall score was used. Chair stands were assessed by asking the participants to fold their arms across their chests and to stand up from a sitting position and then sit down, five times in succession, as quickly as possible [22]. Walking speed was assessed by asking the participants to walk 6 m, or if the participant reported walking slowly, 2.4 m at a self-selected speed [22]. The tests of balance, chair stands and walking speed were derived from the Established Populations for the Epidemiologic Study of the Elderly [23]. Impairment in physical function was defined for each respective test (balance, chair stands and walking speed) as: the inability to stand on one leg for five seconds; the inability to perform five consecutive chair stands and a walking speed of less than 0.8 m/s [24–26]. If persons were unable to perform the test because they were physically unable (e.g. in a wheelchair), they were considered to be impaired in that test. If they were missing data on only one test but were either impaired or unimpaired consistently in both of the other two tests, then they were considered to be impaired or unimpaired, respectively, in the test that was not performed. If they were missing data on two or more tests, without a physical restriction (e.g. in a wheelchair) to explain the missing data, they were excluded (N = 122, 29, 31 from each study interval respectively) from analyses.

Statistical methods

Estimates of point prevalence at each of the three assessment intervals and differences in the magnitude and direction of each point prevalence between consecutive study intervals, as well as between the first and last study intervals, were derived from logistic regression models. A negative amount of change indicates that the level of impairment decreased in the more recent study interval and thus represents an improvement in physical function.

Finally, logistic regression was used to examine each age cohort longitudinally to assess change over time in each of the three measures (balance, chair stands and walking speed), stratified by starting impairment status. The 6-year change in functional status was examined for the 2001–04 cohort and the 2007–10 cohort. For each measure of physical function, and by age and starting impairment status (impaired/unimpaired), the proportion was calculated for those who remained unimpaired/impaired, those who became unimpaired/impaired, and those who died before the subsequent 6-year study assessment. The main analyses were controlled for sex and stratified by age category, and in the secondary analyses, we performed sex-stratified analyses.

Statistical significance was based on P-values <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA/SE 14.1 software (TX, USA).

Results

Temporal trends in point prevalence of impairments

The number of SNAC-K participants and point prevalence (per 100) of impairment in physical function at each assessment, stratified by age group, are reported in Table 1, and stratified by age group and sex reported in Table S1 in the Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online.

Table 1.

Number of SNAC-K participants and point prevalence (per 100) of impairment in physical function (measured with tests of balance, chair stands and walking speed) at each of the three assessments during the period 2001–16 in the Kungsholmen district of Stockholm, Sweden, stratified by age group.

| 2001–04 | 2007–10 | 2013–16 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | N | % Impaired | N | % Impaired | N | % Impaired |

| Balance | ||||||

| 66 | 555 | 14.6 | 592 | 11.3 | ||

| 72 | 454 | 23.8 | 425 | 24.7 | 493 | 20.7 |

| 78 | 441 | 46.0 | 329 | 53.2 | 335 | 42.1 |

| 81/84 | 425 | 67.1 | 465 | 71.6 | 410 | 69.0 |

| 87/90 | 391 | 91.6 | 222 | 89.6 | 238 | 93.3 |

| Chair stands | ||||||

| 66 | 555 | 7.2 | 592 | 5.7 | ||

| 72 | 454 | 10.4 | 425 | 13.2 | 493 | 8.1 |

| 78 | 441 | 24.7 | 329 | 29.2 | 335 | 18.8 |

| 81/84 | 425 | 40.0 | 465 | 46.5 | 410 | 30.5 |

| 87/90 | 391 | 70.0 | 222 | 62.2 | 238 | 57.1 |

| Walking speed | ||||||

| 66 | 555 | 7.2 | 592 | 4.9 | ||

| 72 | 454 | 14.8 | 425 | 10.4 | 493 | 9.7 |

| 78 | 441 | 30.4 | 329 | 34.4 | 335 | 19.7 |

| 81/84 | 425 | 48.0 | 465 | 50.5 | 410 | 40.0 |

| 87/90 | 391 | 76.7 | 222 | 69.8 | 238 | 72.3 |

Point prevalence of impairment in physical function by age in 2001–04 were similar to those in 2007–10 (Figure 1, Tables 1 and 2). However, point prevalence of impairment tended to be lower by age in 2013–16 than in 2007/10 or than in 2001–04, especially for chair stands and walking speed. Point prevalence of impairment were significantly lower at 2013/16 than 2001–04 in chair stands amongst age groups 78, 81/84 and 90 years, and in walking speed amongst age groups 72, 78 and 81/84 years (P < 0.05) (Tables 1 and 2). For balance, the point prevalence of impairment remained quite stable from 2001–04 to 2013–16 in all age groups (P > 0.05).

Table 2.

Change in impairment point prevalence (per 100) in physical function (measured with tests of balance, chair stands and walking speed) between each of the three assessments amongst SNAC-K participants during the period 2001–16 in the Kungsholmen district of Stockholm, Sweden, stratified by age, and adjusted by sex.

| Age (years) | Difference in impairment point prevalence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001–04 to 2007–10 | P | 2007–10 to 2013–16 | P | 2001–04 to 2013–16 | P | ||||

| Change | (95% CI) | Change | (95% CI) | Change | (95% CI) | ||||

| Balance | |||||||||

| 66 | −3.2 | (−7.1, +0.6) | 0.102 | ||||||

| 72 | +0.9 | (−4.7, +6.6) | 0.752 | −4.0 | (−9.4, +1.5) | 0.152 | −3.1 | (−8.4, +2.2) | 0.259 |

| 78 | +7.1 | (+0.02, +14.3) | 0.049 | −11.1 | (−18.7, −3.6) | 0.004 | −4.0 | (−11.0, +3.1) | 0.270 |

| 81, 84 | +4.6 | (−1.4, +10.7) | 0.136 | −2.3 | (−8.4, +3.8) | 0.455 | +2.3 | (−4.0, +8.6) | 0.474 |

| 87, 90 | −1.5 | (−6.3, +3.3) | 0.544 | +3.4 | (−1.7, +8.4) | 0.155 | +1.9 | (−2.4, +6.1) | 0.387 |

| Chair stands | |||||||||

| 66 | −1.5 | (−4.3, +1.4) | 0.318 | ||||||

| 72 | +2.8 | (−1.4, +7.1) | 0.194 | −5.0 | (−9.0, −1.0) | 0.015 | −2.2 | (−5.9, +1.5) | 0.248 |

| 78 | +4.5 | (−1.9, +10.8) | 0.166 | −10.4 | (−16.8, −3.9) | 0.002 | −5.9 | (−11.7, −0.06) | 0.048 |

| 81, 84 | +6.5 | (+0.01, +0.13) | 0.050 | −15.8 | (−22.1, −9.4) | <0.001 | −9.3 | (−15.7, −2.8) | 0.005 |

| 87, 90 | −3.4 | (−11.4, +4.5) | 0.395 | −5.2 | (−14.2, +3.7) | 0.251 | −8.7 | (−16.6, −0.84) | 0.030 |

| Walking speed | |||||||||

| 66 | −2.3 | (−5.1, +0.5) | 0.103 | ||||||

| 72 | −4.4 | (−8.8, −0.05) | 0.048 | −0.6 | (−4.5, +3.3) | 0.776 | −5.0 | (−9.1, −0.8) | 0.020 |

| 78 | +4.3 | (−2.3, +11.0) | 0.205 | −14.6 | (−21.2, −7.9) | <0.001 | −10.2 | (−16.3, −4.2) | 0.001 |

| 81, 84 | +2.6 | (−3.9, +9.2) | 0.430 | −10.0 | (−16.6, −3.5) | 0.003 | −7.4 | (−14.1, −0.7) | 0.030 |

| 87, 90 | −5.9 | (−13.2, +1.4) | 0.114 | +1.8 | (−6.4, +10.0) | 0.666 | −4.1 | (−11.1, +3.0) | 0.257 |

Negative change indicates a decrease in prevalence of impairment and thus indicates an improvement in physical performance in the more recent assessment period.

Temporal trends in 6-year changes in impairment status

Age cohorts were examined longitudinally to assess changes in physical function between the first and second time points and between the second and third time points (please see Table S2A, B and C in the Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online. The proportions of people who were unimpaired, impaired or had died at the end of the 6-year interval are presented below separately for those who were unimpaired and those who were impaired at the start of the time interval.

Among people who were unimpaired at start of the 6-year interval

Proportions of people who remained unimpaired

Those who were unimpaired during the 2007–10 assessment were often more likely to remain unimpaired during the subsequent assessment 6 years later, compared with those who were unimpaired during the 2001–04 assessment. This trend was significant for the youngest three age cohorts (66, 72 and 78 years) for balance and for chair stands, and for age cohorts 72, 78 and 87/90 years for walking speed (please see Table S2A, B and C in the Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online.

Proportions of people who became impaired

There was some consistent evidence that those who were unimpaired during the 2007–10 assessment were less likely to be impaired at the assessment 6 years later, compared with those who were unimpaired during 2001–04. This finding was significant for the 72-year age cohort for balance, for the youngest two age cohorts (66 and 72 years) for chair stands, and for the 72- and 78-year age cohorts for walking speed (please see Table S2A, B and C in the Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online.

Proportions of people who died

There was also some consistent evidence that mortality prior to the assessment 6 years later was less for those unimpaired in 2007–10 compared with those unimpaired in 2001–04. This difference was significant or borderline significant for the four youngest age groups for balance and for chair stands, and borderline significant for the youngest two age groups for walking speed (please see Table S2A, B and C in the Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online.

Among people who were impaired at start of the six-year interval

For those impaired at either 2001–04 or 2007–10, there were no significant differences found in transitions 6 years later to either remaining impaired, becoming unimpaired or dying before the subsequent 6-year assessment, for either balance or chair stands. However, for the 66-year age cohort, there was a significant increase in the proportion of persons impaired in walking speed at 2007–10 who remained impaired 6 years later, relative to the earlier 6-year study interval. For the 72-year age cohort, there was a significant increase in the proportion with walking speed impairment improving to non-impairment 6 years later, in the second study interval (please see Table S2A, B and C, in the Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online.

Proportions of people lost to follow-up

The proportion of persons who remained alive at the end of the interval but did not participate at the latter assessment, did not differ significantly between the first and second intervals, for either people who were unimpaired or impaired at the start of the time interval (please see Table S2A, B and C, in the Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online.

Sex-stratified analyses

Further sex-stratified secondary analyses revealed that the positive time trends in physical function were more evident among women than among men (please see Table S3A and B, in the Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online.

Discussion

Our results suggest a trend towards less functional impairment in older adults, in the most recent 6 years. The improvements appear to be driven by improved prognosis among those without impairments rather than any substantial changes in prognosis for those with impairments.

Our findings are consistent with a few other studies that have also reported improvements in physical functioning of older adults. For instance, a Swedish study found a stable trend in walking speed limitation, with a tendency towards improvement, when comparing two cohorts of Swedish 75-year olds born 18 years apart [11]. However, this study used only one objective measure of physical performance, one age cohort and two time points, the most recent of which was more than 10 years ago. A German study found steady levels in physical functioning from 2006 to 2012 for adults aged 65–90, with a tendency towards improvement in functioning for those aged 75–90 [12]. This study examined a range of ages, however again only two time points were assessed, and the measure of physical functioning was self-reported. Furthermore, a Swedish study examining temporal trends from 1992 to 2011 found a tendency towards a decline in impaired mobility and impaired physical function from 2002 to 2011 [13]. However, although a range of ages were included in the study population, there were no stratified analyses based on age. Also, physical function was assessed by self-report.

The longitudinal population-based study used for these analyses was well designed, had high participation rates at each assessment and provided well-validated measurements for each of the three performance measures of physical function during the study period from 2001 to 2016. These advantages notwithstanding, some limitations need to be taken into account. We need to be cautious in generalising our results, as our study is based on an urban population living in Sweden, which has a high socio-economic standard and a universal healthcare system. However, our previous findings on disability trends were consistent with the findings from other parts of Sweden [3, 4], as well as from the Netherlands [5] and Denmark [6], suggesting that our population is not substantially different from other ageing cohorts. Regarding the comparisons that failed to attain statistical significance, the issue could be partly related to insufficient power. For instance, there were fewer unimpaired persons in the oldest ages, which could explain the lack of significance when evaluating 6-year change from a starting status of non-impairment amongst the oldest age cohorts. There appeared to be a tendency towards increased recovery from impairment in balance and walking speed in the younger ages during the more recent study interval. The lack of statistical significance could be related to the low prevalence of impairment amongst the youngest age cohorts. However, as age was so highly correlated with impairment, we felt it critical to stratify by age.

Another important aspect to consider in interpreting the prevalence of impairment is the cut-off point used to define impairment for each test of objective physical performance. We selected the cut-off points based on previous literature that have shown that physical performance (balance [25, 27], chair stands [28] and walking speed [24, 29, 30]) below these thresholds has been associated with an increased likelihood of adverse outcomes, such as injurious falls, disability, morbidity and mortality. Although, the cut-off points may indicate different levels of difficulty for each test, this study did not attempt to assess what cut-off points would yield comparable prevalence levels of impairment between tests.

The fact that the recent improving trend in physical function appears to be driven by improved prognosis amongst those without impairments (increased tendency to remain unimpaired, decreased tendency to become impaired and decreased tendency to die within 6 years) is consistent with the previous findings reported from this study population, in which improvements in temporal trends of ADL disability were connected with decreased mortality over time among the non-disabled persons [2]. The current findings are encouraging, suggestive that there tends to be a reduction in the probability of becoming impaired, as well as a tendency towards a reduction in mortality within 6 years. It is promising that, regardless of the inclusion of more recent data and study measures, this study echoes the improvements in temporal trends of ADL disability already observed in this study population. While disability is a construct based on physical functioning of individuals within their environments [10], the functional impairments in our study have been objectively measured and are less related to evolving improvements in assistive technologies and more accessible environments [3]. The present study also extends the findings from our previous study, which included people over 80, by showing an improved prognosis among the unimpaired across a wider range of ages. In contrast to our findings, a study on older adults from the USA found that life expectancy increased among those with mobility problems, but not among those without mobility problems [9]. Both incidence of and survival with impaired functioning, such as disability and physical impairment, may vary in different countries due to numerous factors that influence the risk, development and consequences of impaired functioning. Additional studies are justified in order to compare temporal trends, especially within the most recent 10 years and in other geographic settings.

In the supplementary analyses, we have presented findings that indicate significant improvements in function among women but not men. As there are more women than men in our population, and as we lose power by stratifying simultaneously by both sex and age cohorts, it is unclear if this sex difference is real, or if it is an artefact of sample size. Future studies are warranted with larger study populations, to confirm age- and sex-specific temporal trends in objectively measured physical function.

Conclusion

Our results point towards less functional impairments in the most recent years. Our findings are consistent with and build upon previous research by suggesting that unimpaired older adults not only seem to gain in life expectancy, but that they also may be increasingly more likely to maintain a good functional ability. If confirmed in further studies, this trend towards a healthier ageing may offer a more optimistic view of ageing.

Key points.

Prevalence of impairment was lower in 2013–16 than in 2001–04 in chair stands and walking speed amongst most age cohorts.

The decrease in impairment in chair stands and walking speed primarily occurred in the most recent years.

Prevalence of impairment in balance remained substantially unchanged over the 12-year period.

The trend towards less functional impairment appear to be driven by improved prognosis amongst those without impairments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

In addition to the funding agencies, we thank all the SNAC-K participants for their invaluable contributions and our colleagues in the SNAC-K study team for their collaboration in data collection and management.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

This work was supported by various funding sources. The Swedish National study of Aging and Care-Kungsholmen (SNAC-K) population study is supported by the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs and the participating county councils and municipalities. This study was further supported by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskaprådet) (grant numbers 521-2014-21-96; 2013-8676).

References

- 1. Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet 2009; 374: 1196–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Angleman SB, Santoni G, Von Strauss E, Fratiglioni L. Temporal trends of functional dependence and survival among older adults from 1991 to 2010 in Sweden: toward a healthier aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015; 70: 746–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Falk H, Johansson L, Ostling S et al. . Functional disability and ability 75-year-olds: a comparison of two Swedish cohorts born 30 years apart. Age Ageing 2014; 43: 636–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Parker MG, Ahacic K, Thorslund M. Health changes among Swedish oldest old: prevalence rates from 1992 and 2002 show increasing health problems. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005; 60: 1351–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Gool CH, Picavet HS, Deeg DJ et al. . Trends in activity limitations: the Dutch older population between 1990 and 2007. Int J Epidemiol 2011; 40: 1056–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christensen K, Thinggaard M, Oksuzyan A et al. . Physical and cognitive functioning of people older than 90 years: a comparison of two Danish cohorts born 10 years apart. Lancet 2013; 382: 1507–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. (OECD) OfEC-oaD Trends in Severe Disability Among Elderly People: Assessing the Evidence in 12 OECD Countries and the Future Implications. In: OECD Health Working Papers. vol. 26 Paris, 2007.

- 8. Lin SF, Beck AN, Finch BK, Hummer RA, Masters RK. Trends in US older adult disability: exploring age, period, and cohort effects. Am J Public Health 2012; 102: 2157–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crimmins EM, Beltran-Sanchez H. Mortality and morbidity trends: is there compression of morbidity? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2011; 66: 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schoeni RF, Freedman VA, Martin LG. Why is late-life disability declining? Milbank Q 2008; 86: 47–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Horder H, Skoog I, Johansson L, Falk H, Frandin K. Secular trends in frailty: a comparative study of 75-year olds born in 1911–12 and 1930. Age Ageing 2015; 44: 817–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steiber N. Population aging at cross-roads: diverging secular trends in average cognitive functioning and physical health in the older population of Germany. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0136583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fors S, Thorslund M. Enduring inequality: educational disparities in health among the oldest old in Sweden 1992–2011. Int J Public Health 2015; 60: 91–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ahacic K, Parker MG, Thorslund M. Mobility limitations in the Swedish population from 1968 to 1992: age, gender and social class differences. Aging (Milano) 2000; 12: 190–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ahacic K, Parker MG, Thorslund M. Mobility limitations 1974–1991: period changes explaining improvement in the population. Soc Sci Med 2003; 57: 2411–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ahacic K, Parker MG, Thorslund M. Aging in disguise: age, period and cohort effects in mobility and edentulousness over three decades. Eur J Ageing 2007; 4: 83–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Minneci C, Mello AM, Mossello E et al. . Comparative study of four physical performance measures as predictors of death, incident disability, and falls in unselected older persons: the insufficienza cardiaca negli anziani residenti a dicomano study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63: 136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perera S, Patel KV, Rosano C et al. . Gait speed predicts incident disability: a pooled analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015; 71: 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Welmer AK, Rizzuto D, Laukka EJ, Johnell K, Fratiglioni L. Cognitive and physical function in relation to the risk of injurious falls in older adults: a population-based study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016; 72: 669–75. 10.1093/gerona/glw1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lagergren M, Fratiglioni L, Hallberg IR et al. . A longitudinal study integrating population, care and social services data. The Swedish National study on Aging and Care (SNAC). Aging Clin Exp Res 2004; 16: 158–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rossiter-Fornoff JE, Wolf SL, Wolfson LI, Buchner DM. A cross-sectional validation study of the FICSIT common data base static balance measures. Frailty and Injuries: Cooperative Studies of Intervention Techniques. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995; 50: M291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seeman TE, Charpentier PA, Beerkman LF et al. . Predicting changes in physical performance in a high-functioning elderly cohort: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Gerontol 1994; 49: M97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L et al. . A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 1994; 49: M85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW et al. . Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people--results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 1675–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Romero L, Baumgartner RN, Rubenstein LZ, Garry PJ. One-leg balance is an important predictor of injurious falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997; 45: 735–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ward RE, Leveille SG, Beauchamp MK et al. . Functional performance as a predictor of injurious falls in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63: 315–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heiland EG, Welmer AK, Wang R et al. . Association of mobility limitations with incident disability among older adults: a population-based study. Age Ageing 2016; 45: 812–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang F, Ferrucci L, Culham E, Metter EJ, Guralnik J, Deshpande N. Performance on five times sit-to-stand task as a predictor of subsequent falls and disability in older persons. J Aging Health 2013; 25: 478–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abellan van Kan G, Rolland Y, Andrieu S et al. . Gait speed at usual pace as a predictor of adverse outcomes in community-dwelling older people an International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (IANA) Task Force. J Nutr Health Aging 2009; 13: 881–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Studenski S, Perera S, Patel K et al. . Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA 2011; 305: 50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.