Summary

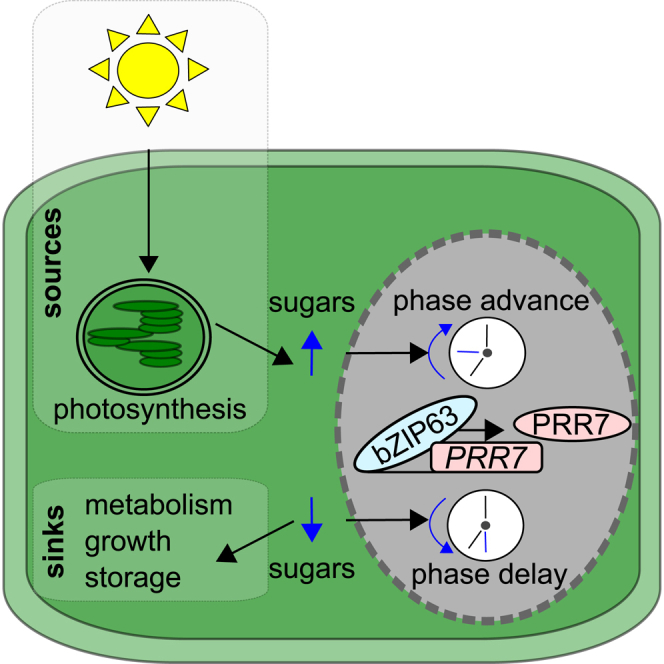

Synchronization of circadian clocks to the day-night cycle ensures the correct timing of biological events. This entrainment process is essential to ensure that the phase of the circadian oscillator is synchronized with daily events within the environment [1], to permit accurate anticipation of environmental changes [2, 3]. Entrainment in plants requires phase changes in the circadian oscillator, through unidentified pathways, which alter circadian oscillator gene expression in response to light, temperature, and sugars [4, 5, 6]. To determine how circadian clocks respond to metabolic rhythms, we investigated the mechanisms by which sugars adjust the circadian phase in Arabidopsis [5]. We focused upon metabolic regulation because interactions occur between circadian oscillators and metabolism in several experimental systems [5, 7, 8, 9], but the molecular mechanisms are unidentified. Here, we demonstrate that the transcription factor BASIC LEUCINE ZIPPER63 (bZIP63) regulates the circadian oscillator gene PSEUDO RESPONSE REGULATOR7 (PRR7) to change the circadian phase in response to sugars. We find that SnRK1, a sugar-sensing kinase that regulates bZIP63 activity and circadian period [10, 11, 12, 13, 14] is required for sucrose-induced changes in circadian phase. Furthermore, TREHALOSE-6-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE1 (TPS1), which synthesizes the signaling sugar trehalose-6-phosphate, is required for circadian phase adjustment in response to sucrose. We demonstrate that daily rhythms of energy availability can entrain the circadian oscillator through the function of bZIP63, TPS1, and the KIN10 subunit of the SnRK1 energy sensor. This identifies a molecular mechanism that adjusts the circadian phase in response to sugars.

Keywords: circadian rhythms, signal transduction, metabolism, sugar signaling

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

The transcription factor bZIP63 binds and regulates the circadian clock gene PRR7

-

•

bZIP63 is required for adjustment of circadian period by sugars

-

•

Trehalose-6-phosphate metabolism and KIN10 signaling regulate circadian period

-

•

Sugar signals establish the correct circadian phase in light and dark cycles

Frank et al. identify mechanisms by which the Arabidopsis circadian clock entrains to sugars. Metabolic adjustment of circadian phase involves trehalose-6-phosphate, SnRK1 subunit KIN10 and the transcription factor bZIP63. bZIP63 regulates the circadian clock gene PSEUDORESPONSE REGULATOR7. This sets the circadian phase in light and dark cycles.

Results

bZIP63 Regulates a Response of the Circadian Oscillator to Sugars

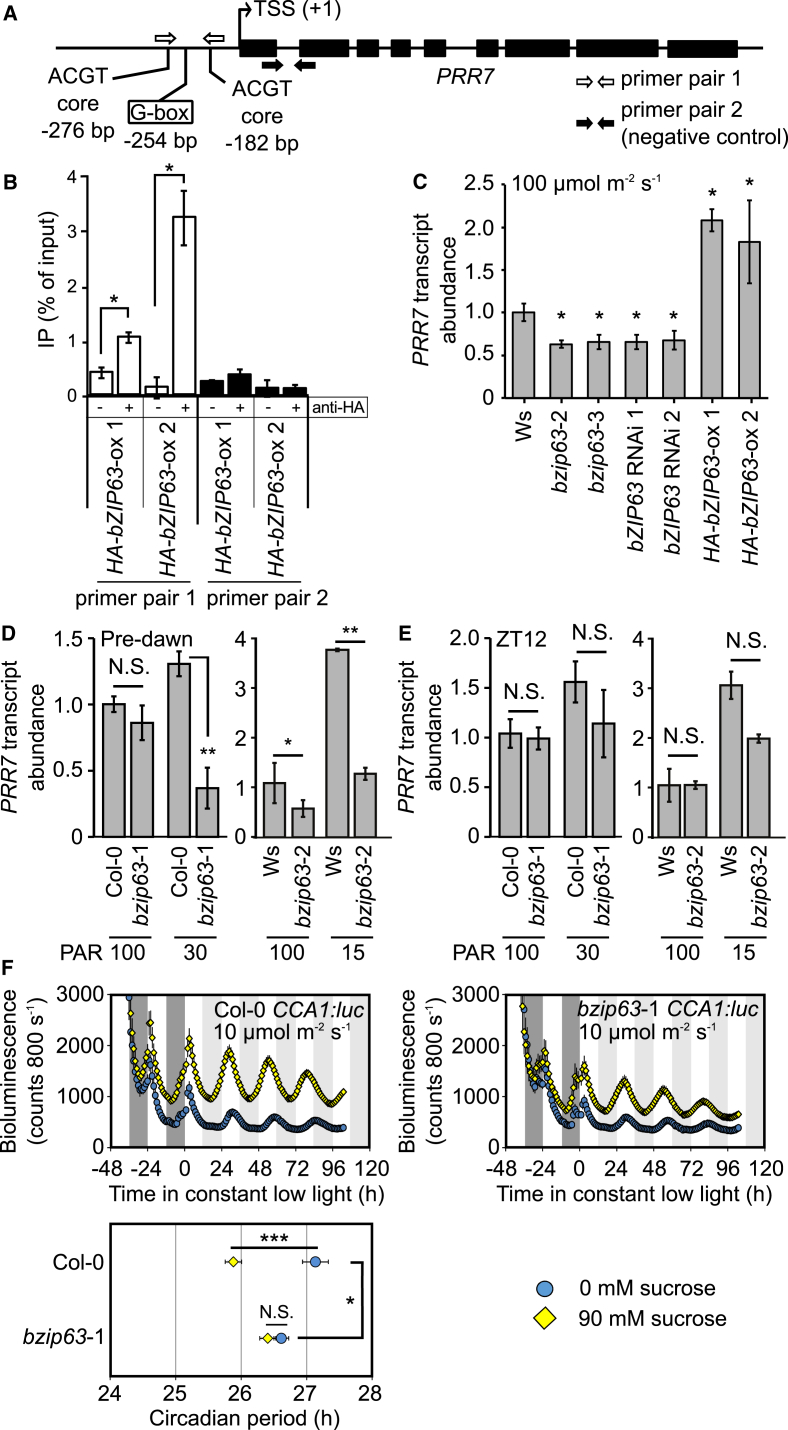

Circadian entrainment to sugars involves the regulation of PRR7 transcription [5]. In response to sugars, the wild-type circadian period shortens, whereas that of prr7-11 does not [5]. Previous investigation of candidate regulators of PRR7 failed to identify candidates affecting the response of the circadian oscillator to sugars [5, 15]. We hypothesized that the transcription factor (TF) bZIP63 might regulate PRR7 because bZIP63 is regulated by the SnRK1 energy sensor and bZIP63 transcripts peak before PRR7 in constant light (Figure S1A). bZIP63 is a strong candidate for sugar-mediated regulation of the circadian oscillator because it binds ACGT core element motifs [16], and the PRR7 promoter contains five ACGT-core bZIP TF-binding motifs within 300 bp of its transcription start site, including a canonical G-box at −254 bp [11, 17, 18, 19] (Figure 1A). bZIP63 binds a PRR7 promoter region spanning −276 to −182 (Figures 1A and 1B; primer pair 1). PRR7 transcripts were downregulated in T-DNA insertion mutants and RNAi lines of bZIP63 (Figures 1C, S1B, and S1C) and upregulated in bZIP63 overexpressors (Figures 1C and S1B). We measured PRR7 transcript abundance under normal and low light, which mimics starvation, demonstrated by accumulation of the marker transcript DARK INDUCIBLE6 (DIN6) [5, 17] (Figure S1D). Under low-light conditions that deplete endogenous sugars, PRR7 transcripts accumulated in the wild-type before dawn (Figure 1D [5]), whereas this was attenuated in bzip63 mutants (Figure 1D). Under high light, which elevates endogenous sugars (Figure S1D [5]), bzip63 mutations had little effect on PRR7 transcript abundance; bzip63-1 was without effect and bzip63-2 reduced PRR7 transcript abundance slightly (Figure 1D). Sucrose supplementation and high light both suppress PRR7 transcript accumulation (Figure 1D) [5], and bzip63 mutants prevent PRR7 upregulation under low light (Figures 1D and 1E). These data suggest that bZIP63 upregulates PRR7 in low-energy conditions and that bzip63-2 is a stronger allele (Figure 1D). At the end of the photoperiod, the bzip63 mutations did not affect PRR7 transcript abundance, consistent with the effects of sugar on PRR7 being restricted to the early photoperiod (Figure 1E) [5]. PRR7 transcripts decreased in bzip63-2 only at the night end, whereas CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED1 (CCA1) and its target GBS1 were upregulated at ZT20-24 (Figure S1E). Upregulation of CCA1 in bzip63-2 might be due to downregulation of PRR7. Therefore, bZIP63 upregulates PRR7 in response to low energy. This is suppressed by sugars because both sucrose supplementation and bzip63 mutants inhibit PRR7 transcript accumulation.

Figure 1.

bZIP63 Binds the PRR7 Promoter to Regulate the Circadian Oscillator

(A) PRR7 structure indicating promoter motifs, transcription start site (TSS), and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-PCR primers. Black rectangles indicate exons.

(B) bZIP63 binds the PRR7 promoter (n = 3 (HA-bZIP63-ox1) and n = 6 (HA-bZIP63-ox2); ±SD); − indicates mock and + indicates immunoprecipitated samples. ChIP used material harvested at end of dark period.

(C) PRR7 transcripts at ZT0 under high light in bzip63 mutant and RNAi lines, and bZIP63 overexpressors (n = 3 ± SD; t test).

(D and E) bZIP63 regulates PRR7 transcript abundance in low, but not high, fluence light/dark cycles. PRR7 transcript abundance immediately before (D) dawn and (E) dusk in mature plants exposed to low light 1 day before sampling (n = 5 ± SD; t test).

(C–E) Significance is indicated for comparisons against wild-type at 100 μmol m–2 s–1.

(F) Sucrose shortened the circadian period of CCA1:luc in Col-0 (t test), but not bzip63-1 (n = 32; ± SEM). Dark and light gray shading indicates actual and subjective darkness, respectively.

See also Figure S1.

Because we found a PRR7-mediated circadian system-wide effect of bZIP63, we investigated whether bZIP63 underlies a response of the circadian oscillator to sugars. Unlike the wild-type, bzip63-1 circadian period was unaffected by sucrose under low light (Figure 1F), indicating that the circadian oscillator in bzip63-1 is sugar unresponsive. This suggests the circadian oscillator did not respond to sugars in bzip63-1 because PRR7 was not upregulated by low-energy conditions.

Sugar-Induced Changes in Circadian Period Involve KIN10 and Trehalose-6-Phosphate Biosynthesis

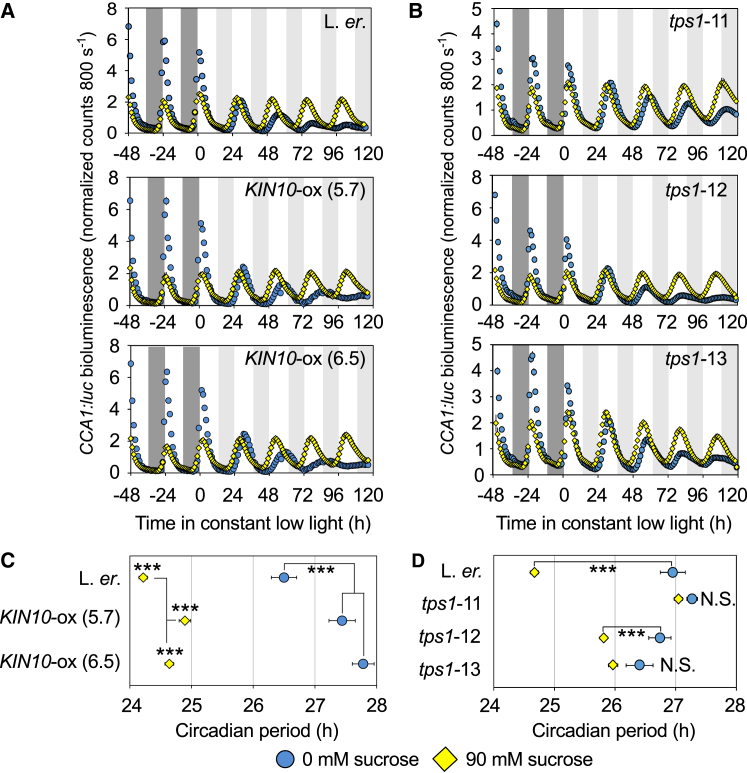

We investigated how regulators of bZIP63 influence the response of the circadian oscillator to sugars. KIN10 (AKIN10/SnRK1.1), an α subunit of the sugar sensor SnRK1 [17], regulates bZIP63 activity in response to starvation [11]. KIN10 overexpression (KIN10-ox; Figure S1F) [17] further increased the long circadian period of the wild-type occurring under low-energy conditions (Figures 2A and 2C). The circadian system in KIN10-ox remained sugar sensitive because sucrose supplementation shortened its period (Figure 2C) [5]. This could be because overexpressed KIN10 is inhibited post-translationally by sugars. Constitutive KIN10 overexpression under high light, when sugars are high, did not lengthen the period (Figure S2A).

Figure 2.

KIN10 and TPS1 Regulate the Response of the Arabidopsis Circadian Clock to Sugar

(A and B) CCA1:luc bioluminescence in low light, with/without exogenous sucrose in (A) two KIN10-ox lines (n = 37–58; three experiments combined) and (B) three tps1 mutants (n = 36–64; six experiments combined). Dark and light gray panels indicate actual and subjective darkness, respectively.

(C and D) Circadian period of CCA1:luc bioluminescence in KIN10-ox (C) and tps1 mutants (D), relative to wild-types, with or without exogenous sucrose under low light (t test; ±SEM).

Under low-energy conditions, such as low light, KIN10-ox caused a longer period relative to the wild-type (Figure 2C). Under high-energy conditions (either low light plus sucrose or high light), KIN10-ox had less effect (Figures 2C and S2A). Therefore, sugar levels affect the circadian phenotype in KIN10-ox. This is consistent with KIN10 regulating the circadian clock in response to energy status because low-energy conditions cause a longer period [5], KIN10 is activated by low energy [14, 17], and sucrose rescues light-intensity-dependent effects of KIN10 upon the circadian oscillator [14].

TREHALOSE-6-PHOSPHATE SYNTHASE1 (TPS1) synthesizes the signaling sugar trehalose-6-phosphate (Tre6P). Tre6P concentration tracks sucrose and negatively regulates SnRK1 activity, bZIP63, and other sugar-sensing targets [11, 20, 21]. We investigated the circadian phenotype of three hypomorphic tps1 TILLING mutants [22]. Sucrose had no effect on period in tps1-11 and tps1-13 (Figures 2B and 2D). Sucrose shortened the period of tps1-12, the weakest allele for metabolite alterations [22], but less than the wild-type (Figure 2D). In the presence of sucrose, all three tps1 alleles had longer periods than the wild-type (Figure 2D), presumably because low Tre6P mimics starvation. In the absence of sucrose under low-light conditions, tps1 mutants did not have a longer period than the wild-type (Figure 2D). This might be because these seedlings were already in a low-sugar state [5], so disrupting this pathway caused no further change.

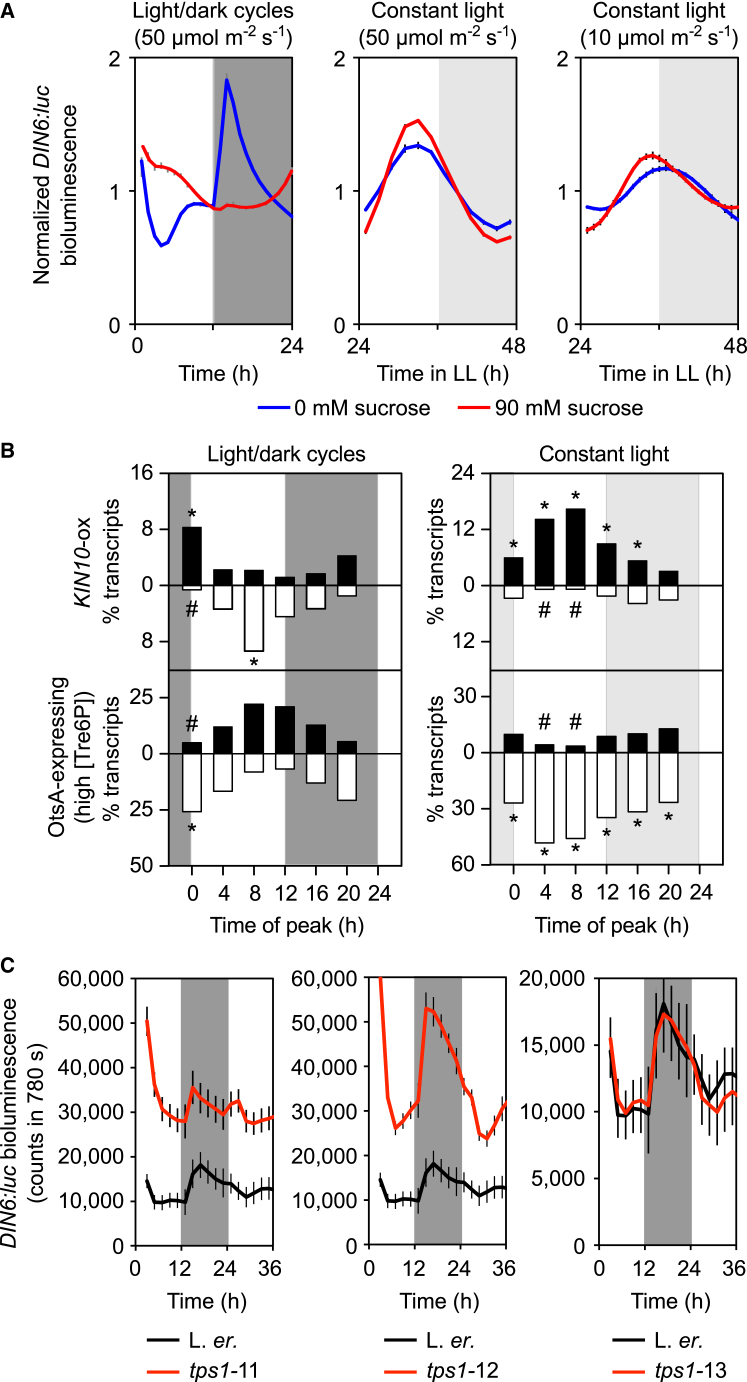

Diel and Circadian Rhythms of Sugar Signaling Revealed by DIN6 Promoter Dynamics

Energy changes might arise from fluctuations in sucrose availability [23]. We investigated this using DARK INDUCIBLE6 (DIN6/ASN1), which is upregulated by starvation, downregulated by sugars, and downstream of the regulation of bZIP63 by KIN10 [11, 17]. DIN6:luc had a diel rhythm, with promoter activity (2.4-fold; Figure 3A) and transcript abundance (2.7-fold; Figure S2B) increasing after dusk. DIN6 promoter activity reduced through the night, presumably as sugars became available from starch breakdown [28]. After dawn, DIN6:luc activity decreased rapidly, suggesting the accumulation of photosynthetic sugars (Figure 3A). DIN6 promoter dynamics in light/dark cycles arose from sugar status alterations, because sucrose supplementation attenuated DIN6:luc rhythms (Figure 3A). This is also supported by increased DIN6 transcript abundance under low-light/dark cycles at pre-dawn and dusk compared with high-light controls (Figure S1D). DIN6 promoter activity and transcript accumulation are also circadian regulated, peaking in the middle of the subjective day in constant high light (LL) (Figures 3A and S2C). As with CCA1:luc [5], DIN6:luc was phase-advanced by sucrose under constant low light but not higher light intensity. Therefore, under light/dark cycles there are sugar-dependent cycles in a readout of KIN10- and bZIP63-mediated sugar signaling [11, 17]. This indicates that starvation pathways are upregulated during each night of light-dark cycles (Figures 3A and S2B). Extensive integration of circadian regulation with energy signaling is corroborated by statistically significant overlaps between KIN10- and [Tre6P]-regulated transcripts and five sets of circadian- and diel-regulated transcripts (Figures 3B and S2D–S2F) [17, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27].

Figure 3.

Diel Cellular Energy Signaling Dynamics

(A) Normalized DIN6:luc bioluminescence dynamics (n = 6; ±SEM).

(B) A significant proportion of circadian [24, 25, 26] and diel-regulated [23, 27] transcripts are regulated by KIN10 signaling [17, 20]. This analysis combines individual datasets from Figures S2E and S2F. Transcripts binned by phase (upregulated, black; downregulated, white). ∗ and # indicate overlaps with more or fewer transcripts than expected from a chance association between gene sets, respectively.

(C) Under light/dark, DIN6:luc is upregulated in tps1-11 and tps1-12 (n = 6; ±SEM). Dark and light gray shading indicates actual and subjective darkness, respectively.

See also Figures S2 and S3.

Diel cycles of DIN6:luc activity are likely mediated by Tre6P. DIN6:luc activity was increased in two tps1 alleles (tps1-11 and tps1-12), particularly at night when low sugar availability combines with the low TPS1 activity in these mutants to activate KIN10 and the DIN6 promoter [11, 17, 20] (Figure 3C). DIN6:luc was unaltered in tps1-13, which is a weaker allele for some physiological traits [22]. This demonstrates that Tre6P transmits diel changes in sugar status to the bZIP63-responsive promoter DIN6 (Figure 3C) [17, 18].

Circadian Oscillator Protein CHE Interacts with bZIP63 and Regulates a Response of the Circadian Oscillator to Sugar

bZIP TFs undergo regulatory interactions with many other proteins [29]. We investigated whether these might contribute to circadian entrainment by sugars. Using a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screen, we identified interaction between bZIP63 and the circadian oscillator component CCA1 HIKING EXPEDITION (CHE/TCP21) (Figure S3A). Like PRR7, CHE is a transcriptional repressor of CCA1 [30, 31]. No other known regulators of the circadian system interacted with bZIP63. We confirmed that bZIP63 interacts with CHE in planta using bimolecular fluorescence complementation (Figure S3B). We hypothesized that CHE might contribute to a response of the circadian oscillator to sugars. We found that sucrose induces CHE transcripts in the wild-type, but this was attenuated in KIN10-ox and somewhat in tps1-12 (Figure S3C). In light/dark cycles without sucrose supplementation, CHE overexpression and che loss-of-function mutants suppressed and increased the amplitude of daily CCA1:luc fluctuations, respectively (Figures S3D and S3E) [30]. When diel changes in sugar status were eliminated by cultivation on 90 mM sucrose (Figure 3A), the amplitude difference between che mutants and the wild-type was abolished (Figures S3D and S3E). This suggests that CHE might not suppress CCA1 under sugar-replete conditions, and that CHE regulates a response of CCA1 to sugars. This occurred independently from CHE binding to the TCP-binding site (TBS) within the CCA1 promoter [30], because mutation of the TBS did not alter the response of CCA1 to a morning sugar pulse (Figure S3F).

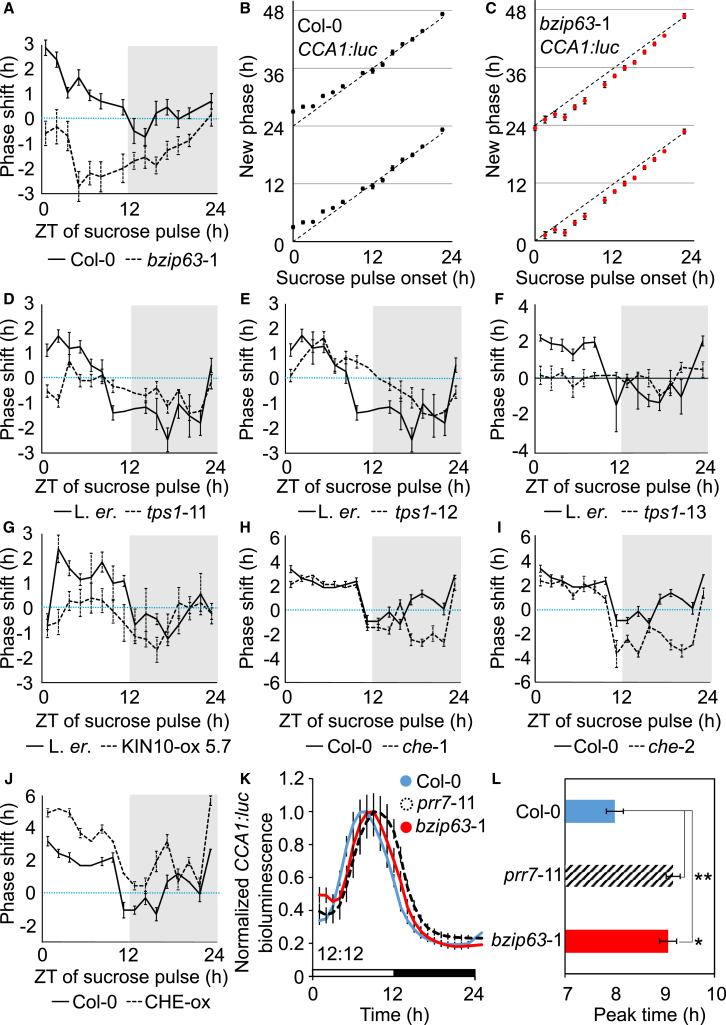

bZIP63, KIN10, and TPS1 Regulate the Response of Circadian Phase to Sugars

To test the potential involvement of bZIP63, KIN10, Tre6P, and CHE in circadian entrainment, we measured the time-dependent adjustment of circadian phase in response to a sucrose pulse. This tests the response of the circadian oscillator to a transient stimulus, as opposed to prolonged sucrose treatments (Figures 1F and 2). A morning sugar pulse (ZT0–ZT6) advanced the wild-type circadian phase (Figures 4A and 4B) [5]. In contrast, morning sugar pulses did not advance the circadian phase in bzip63-1 mutants (Figures 4A and 4C). This demonstrates that sucrose acts as a type 1 (weak) zeitgeber in the wild-type, resulting in a circadian phase advance. This phase advance was absent in bzip63-1. There was also no phase advance in tps1-11, tps1-13, and KIN10-ox in response to morning sucrose pulses (ZT3–ZT7.5, Figures 4D–4G). tps1-12 had a phase advance in response to sucrose pulses at this time (Figure 4E), which is consistent with its weaker metabolic phenotypes [22]. These data suggest that TPS1, KIN10, and bZIP63 might be positioned within a pathway by which sugars entrain the circadian oscillator (Figures 4A–4G).

Figure 4.

TPS1, KIN10, and bZIP63 Entrain the Circadian Oscillator

(A–J) Phase response curves (A and D–J) and phase transition curves (B and C) of CCA1:luc for sucrose treatment of bzip63-1 (A), tps1-11 (D), tps1-12 (E), tps1-13 (F), KIN10-ox (G), che-1 (H), che-2 (I), and CHE-ox (J). x axes indicate zeitgeber time (ZT) of sugar pulse. Blue dotted line indicates phase of a control grown without sucrose.

(K and L) Phase of rhythms of CCA1:luc in Col-0, prr7-11 and bzip63-1 in light/dark cycles of 70 μmol m–2 s–1 in the absence of sucrose (n = 12 ± SEM; t test), plotted as CCA1:luc bioluminescence (K) and time of peak bioluminescence (L). Shaded areas indicate subjective dark period.

In (B) and (C), phase transition curves are double-plotted using data from (A) and indicate new phase against time following a 90 mM sucrose pulse for (B) wild-type and (C) bzip63-1. Dashed line indicates no phase shift. Data from two independent experiments were combined (n = 8 in each; ±SEM).

Two che mutations had little effect upon the morning sucrose-induced phase advance (ZT0–ZT7.5; Figures 4H and 4I), and a sucrose-induced phase delay occurred in che during the subjective night (ZT15–ZT19.5; Figures 4H and 4I). CHE-ox increased the magnitude of the sucrose-induced phase advance of CCA1 at most times of day (Figure 4J). Therefore, CHE is not required for the sugar-induced circadian phase advance in the morning but might be associated with other sugar responses. This is consistent with our hypothesis that circadian entrainment to sugars depends upon PRR7, with the alteration of CCA1 transcription occurring in response PRR7 expression dynamics [5].

Lastly, we examined whether PRR7 and bZIP63 are required for correct circadian function under day/night cycles. prr7-11 and bzip63-1 have a late phase of CCA1 expression (Figures 4K and 4L) demonstrating that bZIP63 and PRR7 are required for correct oscillator phase under light/dark cycles (Figures 4K and 4L). These late-phase phenotypes (Figures 4K and 4L) suggest defective entrainment. Considering that bZIP63 participates in the regulation of the circadian oscillator in response to sugars (Figure 1F), this sugar-responsive entrainment pathway is required to ensure correct circadian phase under light/dark cycles.

Discussion

Our finding that bZIP63 regulates the circadian oscillator allowed us to investigate entrainment of the Arabidopsis circadian oscillator by sugars. We propose that daily fluctuations in sugar availability might be signaled by Tre6P to effect entrainment. Mutants impaired in Tre6P production had a reduced response of circadian period to sucrose (Figures 2B and 2D), and the circadian oscillator of tps1 mutants was not entrained by sucrose (Figures 4D–4F). bZIP63 homo- and heterodimerization is regulated by KIN10-mediated phosphorylation [11], so transcriptional regulation of PRR7 by bZIP63 might arise from bZIP63 phosphorylation dynamics. Mutants of both bzip63 and its negative regulator TPS1 have similar effects on the circadian oscillator because PRR7 cannot respond to sugar dynamics in both sets of mutants. KIN10-ox was insensitive to entraining sugar pulses, suggesting that SnRK1 participates in entrainment to transient sugar fluctuations (Figure 4G). Morning sucrose pulses delayed the phase in bzip63-1 (Figure 4A), whereas the phase in tps1-11 and tps1-13 was sucrose insensitive (Figures 4D and 4F). This difference might reflect additional effects of the tps1 TILLING alleles, which influence a range of phenotypes [22]. Other kinases and pathways might be involved because KIN10-ox seedlings retained a shorter period, like the wild-type, during long-term sucrose supplementation (Figure 2C) [14]. bzip63-1 was unresponsive to prolonged sucrose stimulation (Figure 1F), whereas it retained some sucrose-induced phase changes within the phase response curve (Figure 4A). This is similar to the lip1-1 mutant, which has a very small period response to varying intensity of continuous light, but retains a phase delay response to pulsed light in phase response curves [32]. In continuous darkness, the period of an evening reporter of the circadian oscillator (GIGANTEA) is unaltered in KIN10-ox [14]. This might be because, in continuous darkness, evening components of the circadian oscillator appear to uncouple from morning components such as CCA1 and PRR7 investigated here [5, 15, 33].

We found that bZIP63 binds the PRR7 promoter in a region containing a canonical G-box motif. While bZIP63 might bind to other cis elements within this region, for two reasons it is possible that bZIP63 binds to this −254 bp G-box. First, mutating the G-box within the promoter of another bZIP63- and KIN10-regulated gene, DIN6, abolishes the regulation of DIN6 by KIN10 [17]. Second, bZIP1 binding to G-box motifs is enhanced by heterodimerization with bZIP63 [34, 35].

Our data suggest that the response of bZIP63 and PRR7 to sugar entrains the Arabidopsis circadian clock to dynamic energy signals during light/dark cycles. This will allow identification of other network components, since bZIP63 and other bZIPs are phosphorylated by protein kinases other than KIN10, potentially including KIN11 and casein kinase II [11, 29]. It will be informative to determine whether other bZIP TFs dimerize with bZIP63 to regulate PRR7 transcription and whether binding and/or activity of bZIP63 is regulated by energy status.

bZIP63 works through protein-protein interactions in addition to protein-DNA interactions. We identified potential interactions with CHE, a regulator of CCA1 [30]. This suggests several modes of regulation of bZIP63 activity and that CHE might affect the circadian oscillator through multiple mechanisms. bZIP63 interacts with a further TCP TF, TCP2 [36], suggesting an interacting network of bZIP and TCP TFs. This bZIP63-CHE interaction provides further evidence that TCP TFs are important regulators within the plant circadian system [30, 37, 38, 39]. The bZIP63-CHE interaction might have mechanistic similarities with the coincident binding of interacting TOC1 and PIF3 to promoters of growth-regulating genes [40]. PIF4 is proposed as an additional regulator of circadian entrainment to sugars [41], although PIF4 does not bind the PRR7 promoter [42, 43] and roles for PIF4 within metabolic entrainment remain untested.

Conclusions

Our identification of key molecular components that permit the circadian oscillator to respond to sugars brings a new dimension to the study of plant circadian systems, by identifying a TF that adjusts circadian phase to entrain the oscillator. Our finding that bZIP63 upregulates PRR7 promoter activity in response to low energy suggests that sugars regulate circadian period and phase through a signaling pathway rather than indirect metabolic changes [44]. This underlies the plasticity of the circadian period to sugars, with this plasticity absent from prr7-11 and bzip63 mutants (Figure 1F) [5]. We propose that the dynamic sensitivity of the circadian system to cellular energy, through bZIP63 regulation of PRR7 expression, permits its continuous metabolic adjustment to contribute to energy homeostasis [45]. This is important because circadian systems provide a selective advantage through their phase relationship with the environment [3, 46]. Here, we identified a mechanism that establishes that phase relationship.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| KIN10 antibody | Agrisera | Cat# AS10 919; RRID: AB_10754154 |

| RbcL antibody | Agrisera | Cat# AS03 037A; RRID: AB_2175408 |

| Anti-HA antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat# sc-7392 C1313 |

| H3-K9 antibody | Epigentek | Cat# P-2014-48 |

| Normal mouse IgG antibody | Epigentek | Cat# P-2014-48 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli DH5α | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# 18265017 |

| Escherichia coli DB3.1 | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# A10460 |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 | N/A | N/A |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 | N/A | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Bacto-agar | VWR | Cat# 214050 |

| Duchefa Murashige & Skoog Medium | Melford Laboratories | Cat# M0221.0050 |

| Sucrose | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# 10020440 |

| Sorbitol | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# BP439-500 |

| 3′,5′-dimethoxy-4’-hydroxyacetophenone (Acetoseringone) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D134406 |

| Kanamycin | GIBCO | Cat# 11815-024 |

| Ampicillin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A0166 |

| Rifampicin | Affymetrix | Cat# USB-21246 |

| Tetracycline | Affymetrix | Cat# USB-22105 |

| Phosphinothricin | Melford Laboratories | Cat# P0159.0250 |

| BamHI | New England Biolabs | Cat# R0136S |

| KpnI | New England Biolabs | Cat# R0142S |

| T4 DNA ligase | New England Biolabs | Cat# M0202S |

| SD/-His/-Leu/-Trp/-Ura with Agar | Clontech | Cat# 630325 |

| Drop-out Supplement -Leu/-Trp | Clontech | Cat# 630417 |

| Drop-out Supplement -His/-Leu/-Trp | Clontech | Cat# 630419 |

| 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3AT) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# A8056 |

| Sterile RNase-free water | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# BP561-1 |

| RNaseZap RNase decontamination solution | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# AM9780 |

| Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | New England Biolabs | Cat# M0530S |

| D-luciferin, potassium salt | Melford Laboratories | Cat# L37060 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| EpiQuik Plant ChIP kit | Epigentek | Cat# P-0214-048 |

| pGEM-T easy vector systems kit | Promega | Cat# A1360 |

| pENTR/D-TOPO cloning kit, with One Shot TOP10 chemically competent E. coli | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# K240020 |

| ProQuest two-hybrid system with Gateway Technology | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# PQ1000101 |

| RNEasy Plant Mini kit | QIAGEN | Cat# 74104 |

| Machery-Nagel Nucleospin II RNA kit | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# 12373368 |

| Machery-Nagel Nucleospin Plasmid kit | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# 11932392 |

| High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit | Life Technologies | Cat# 4368814 |

| RNAase inhibitor for reverse transcription kit | Life Technologies | Cat# N8080119 |

| Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix | Agilent Technologies | Cat# 600883 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain PJ694a (MATa, trp1-901, leu2-3,122, ura3-52, his3-200 gal4Δ, gal80Δ, LYS2::GAL1-HIS3, GAL2-ADE2::GAL7-lacZ) | [47] | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Arabidopsis: Col-0 | Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: Wassilewskija | Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: Landsberg erecta | Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: bzip63-1 | [16] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: bzip63-2 | [16] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: bzip63-3 | Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre | Line FLAG_532A10 |

| Arabidopsis: bZIP63 RNAi 1 | This paper | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: bZIP63 RNAi 2 | This paper | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: HA-bZIP63-ox 1 | This paper | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: HA-bZIP63-ox 2 | This paper | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: KIN10-ox 5.7 | [15] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: KIN10-ox 6.5 | [15] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: tps1-11 | [22] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: tps1-12 | [22] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: tps1-13 | [22] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: prr7-11 | [48] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: che-1 | [30] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: che-2 | [30] | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: CHE-ox | [30] | N/A |

| Nicotiana benthemiana | N/A | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S1 | N/A | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pGREENII 0229 binary vector | John Innes Centre, U.K. | pGREENII0229 |

| pSOUP helper vector | John Innes Centre, U.K. | pSOUP |

| CCA1:luc binary vector | [49] | N/A |

| pPZP CCA1(TBSm):luc | [30] | N/A |

| pPZP CCA1:luc | [30] | N/A |

| pDEST22 | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# PQ1000101 |

| pDEST32 | Thermo-Fisher | Cat# PQ1000101 |

| pDEST32:CHE | This paper | N/A |

| pDEST32:bZIP63 | This paper | N/A |

| pDEST22:bZIP63 | This paper | N/A |

| HA-bZIP63-ox in pFP101HAVP16 | [50] | N/A |

| bZIP63 RNAi in pHANNIBAL | [51] | N/A |

| bZIP63 RNAi in pFP100-LacZ | [50] | N/A |

| pSPYNE-35S (YFPN) | [52] | N/A |

| pSPYCE-35S (YFPC) | [52] | N/A |

| pSPYNE-35S:bZIP63 (bZIP63-YFPN) | This paper | N/A |

| pSPYCE-35S:bZIP63 (bZIP63-YFPC) | This paper | N/A |

| pSPYCE-35S:CHE (CHE-YFPC) | This paper | N/A |

| pCH32 | [53] | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Excel | Microsoft | N/A |

| Sigmaplot 13.0 | Systat Software, USA | N/A |

| Inkscape 0.91 | https://inkscape.org/en/ | N/A |

| Biological Rhythms Analysis Software System (BRASS) | University of Edinburgh; http://millar.bio.ed.ac.uk/ | N/A |

| Image32 | Photek, U.K. | N/A |

| Other | ||

| MLR350/352 growth chamber | Sanyo or Panasonic, Japan | N/A |

| Photek HRPCS intensified CCD camera system | Photek, U.K. | N/A |

| LB982 Nightshade | Berthold Technologies, Germany | N/A |

| GFP2 filter equipped SMZ1000 stereomicroscope | Nikon | N/A |

| LSM 510 Confocal Microscope | Zeiss | N/A |

| Zen software | Zeiss | N/A |

| Mx3005P real-time PCR machine | Agilent Technologies | N/A |

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by Antony Dodd (antony.dodd@bristol.ac.uk).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. background lines Columbia-0 (Col-0), Landsberg erecta (L. er.) and Wassilewskija (Ws) were used for experimentation, with mutants and transgenic lines in these backgrounds as detailed in the Key Resources Table. Arabidopsis seedlings were cultivated at 19°C, under light conditions required by each experiment and described in the Results. Nicotiana benthemiana was cultivated at 25°C (both for growth and bimolecular fluorescence complementation analysis). Saccharomyces cerevisiae was cultured at 30°C for all assays.

Method Details

Plant material and growth conditions

Seeds were surface-sterilized with 10% v/v sodium hypochlorite (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) and 0.02% (v/v) Triton X-100 (Fisher Scientific, Loughborough, UK) for 5 min, washed three times with sterile deionised water and sown on half-strength Murashige & Skoog media (Duchefa, Netherlands), pH = 5.7 with 0.8% w/v agar (Bactoagar, BD). Where specified, media was supplemented with 90 mM sucrose or 90 mM sorbitol as an osmotic control. This concentration of sucrose is appropriate for our experiments because it saturates the sugar response of the circadian oscillator, is the standard concentration of sucrose used for experimentation with Arabidopsis, and there is no dose-dependent effect of sucrose upon circadian entrainment [5, 14, 15, 25, 33]. Seeds were stratified at 4°C for 2 or 3 days in darkness, then transferred into 50 μmol m-2 s-1 (before starting low light experiments) or 80 – 100 μmol m-2 s-1 (for standard light experiments) photon flux of cool white fluorescent light, at 19°C, with cycles of 12 hr light and darkness (MLR-350/352 growth chamber, Sanyo/Panasonic, Japan). Background lines for the tps mutants were derived originally from mutagenesis of Col-0 and backcrossed three times with Landsberg erecta (L. er.) [22]. We have, therefore, used L. er. as a control for experiments with tps lines. KIN10-ox was as described elsewhere [17]. T-DNA insertion mutants bzip63-1 (SALK_006531, Col-0 background [18]), bzip63-2 (FLAG_610A08, Ws-2 background [18]) and bzip63-3 (FLAG_532A10, Ws-2 background) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC). Homozygous bzip63-3 was isolated using kanamycin-resistance segregation analysis, and sequencing of the flanking regions revealed that the T-DNA is inserted in the sixth exon of the bZIP63 gene. For experiments using mature plants, Arabidopsis was grown under 12 hr photoperiods of 100 μmol m-2 s-1 for 30 days before experimentation.

Generation of transgenic lines

To make HA-bZIP63-ox and bZIP63 RNAi lines, both the bZIP63 coding sequence (CDS) and a 350 bp fragment for RNAi were amplified using PCR primers that incorporated restriction sites (indicated in lower case); overexpressor: tctaga ATGGAAAAAGTTTTCTCC (FP); ggatccCTACTGATCCCCAACGCT (RP); RNAi: aagcttggtaccTCACTGGTCGGTTAATGG (FP); tctagactcgagCACTTGTTATAGCACTGC (RP). The bZIP63 CDS was cloned into the pFP101 vector, fused to 3xHA tag and the VP16 activation domain for overexpression by the CaMV 35S promoter. The 350 bp bZIP63 fragment was cloned antisense and sense into pHANNIBAL, then transferred to pFP100-Lacz with the CaMV 35S promoter driving antisense-sense hairpin expression.

To produce the DIN6:luciferase construct, 2659 bp of genomic DNA upstream of the DIN6 start codon was isolated by PCR, using primers that introduced the KpnI (5′) and HindIII (3′) restriction sites (FP: CGTGGTACCTGGACATGAGTGCATGAC; RP: GCGAAGCTTGAAGAAAGTGAAAAAGATCACG). The fragment was ligated into a modified pGreenII0179 binary vector containing the LUCIFERASE+ coding sequence [54]. The CCA1:luciferase construct used is described elsewhere [55]. Reporter lines with CCA1(TBSm):luc and control CCA1:luc used constructs in the pPZP binary vector described elsewhere [30]. All constructs were transformed into Arabidopsis by the floral dip method, using Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Transformants were identified with hygromycin (pGreenII0179) or gentamycin (pPZP) selection, or from GFP fluorescence in the seed coat (pFP101 and pFP100-LacZ), using a GFP2-equipped SMZ1000 stereomicroscope. Lines were validated by PCR and RT-PCR, and selected for similar levels of luciferase activity. Homozygous third or fourth generation seed lines were used for experiments.

Bioluminescence imaging

Imaging of luciferase bioluminescence was performed as described previously [5, 54]. Briefly, circular clusters of 9 day old seedlings were supplied with 2 mM (two doses) or 5 mM (single dose) of D-luciferin potassium salt (Melford Labs, UK, or Biosynth AG, Switzerland) between 1 hr and 24 hr prior to commencing imaging. Luciferase bioluminescence was integrated for 800 s each hour using either a Photek HRPCS intensified CCD camera (Photek, Hastings, UK) or LB 982 NightSHADE (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Light was controlled automatically to provide the stated photon irradiance and LD cycles or constant (LL) light from a red/blue LED mix (wavelengths 660 nm and 470 nm). Circadian oscillation parameters were calculated from four 24 hr cycles, excluding the first 24 hr of data, using the Fast Fourier Transform Non-Linear Least-squares method [56] within the BRASS software (http://millar.bio.ed.ac.uk/). The mean peak height parameter was calculated as an average of the differences between peak (maximum value) and trough (minimal value) measured on days 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 of LL (thus excluding first 24 hr), and for LD was calculated by averaging the differences between peaks and troughs measured for each day under light/dark conditions. Phase response curves were produced using the same method as described previously [5, 57].

RNA extraction and real time PCR analysis

Sampling and RNA isolation for real-time PCR was performed as described previously [5, 54]. Primers were PRR7: TTCCGAAAGAAGGTACGATAC (FP); GCTATCCTCAATGTTTTTTATGT (RP); PP2AA3 reference transcript [18]: CATGTTCCAAACTCTTACCTG (FP); GTTCTCCACAACCGCTTGGT (RP) (for Figure 1C); CHE: TAATGGGTGGTGGTGGTTCTG (FP); GCAAAGCTCCAGACTTGTCC (RP); Figure S3C); DIN6: TTCACCTTTCGGCCTACGAT (FP); ATCGGCATGTTGTCAATTGC (RP); ACT2 reference (TGAGAGATTCAGATGCCCAGAA (FP); TGGATTCCAGCAGCTTCCAT (RP) (for Figure S3C).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Aerial parts of 12-day old seedlings were vacuum-infiltrated with 1% v/v formaldehyde solution and incubated at room temperature for 20 min to crosslink DNA-protein complexes. After cross-linking, tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen using mortar and pestle. Chromatin extraction was performed as described elsewhere [58]. The isolated chromatin was re-suspended in 300 μL of nuclear lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCL, pH 8; 10 mM EDTA; 1% w/v SDS; 1X Pierce protease inhibitor cocktail #88265 (Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). Resuspended chromatin was sonicated to achieve DNA fragments ranging 0.3 - 1 Kb. Immunoprecipitation was performed using EpiQuik Plant ChIP kit (Epigentek Group, Farmingdale, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. DNA-protein complexes were immuno-precipitated using a monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Texas, USA). Analysis of enrichment of target genes was performed by qPCR (ABI 7500 Fast Real-time PCR System). For PRR7, primer pair 1 was GACGTTTTCCTTACCCACCA (FP), ATTGGCGAGGATTAGTGACG (RP), and primer pair 2 TGCTTTTGTATGGTTGGATTTTT (FP), TGAAGAACGACGAATTCTCAAA (RP) (Figures 1A and 1B). Data were normalized using cycle thresholds from immunoprecipitated and non-immunoprecipitated samples as elsewhere.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR was performed using two transgenic lines overexpressing HA-tagged bZIP63 (HA-bZIP63-ox1 and HA-bZIP63-ox2 in Figure 1B), using an anti-HA antibody (+) and an anti-mouse IgG antibody (-) as a negative control. ChIP using overexpressor lines is a common approach (e.g., [59, 60]), with the bZIP63 overexpressors accumulating approximately double the transcript as the wild-type under high light at ZT0 (Figure 1C). Primer pair 1 amplifies the promoter region containing G-box motif and primer pair 2 as a control amplifies a region without any putative bZIP binding site. Data in Figure 1B compare the cycle threshold (Ct) of the anti-HA antibody IP samples (adjusted relative to Ct of input DNA) and Ct of mock IP (adjusted relative to Ct of the input DNA); t tests compared control and anti-HA treated samples (HA-bZIP63-ox1 p = 0.011; HA-bZIP63-ox2 p = 0.014).

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation

Full-length coding regions of bZIP63 (AT5G28770.2) and CHE (AT5G08330.1) were cloned using specific primers (CHE: TAAGCAGGATCCATGGCCGACAACGACGGAGC (FP); TAAGCAGGTACCACGTGGTTCGTGGTCGTC (RP); bZIP63: TAAGCAGGATCCATGGAAAAAGTTTTCTCCG (FP); TAAGCAGGTACCCTGATCCCCAACGCTTC (RP) into binary vectors pSPYNE-35S (YFPN terminus; aa 1-155) or pSPYCE-35S (YFPC terminus; aa 156-239) to generate the fusion proteins bZIP63-YFPN, bZIP63-YFPC and CHE-YFPC [52]. The binary vectors containing the constructs bZIP63-YFPN, bZIP63-YFPC and CHE-YFPC were inserted into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1, which was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium containing appropriate antibiotics (100 μg ml-1 rifampicin, 50 μg ml-1 kanamycin, 10 μg ml-1 tetracycline) at 28°C for 16 hr and 200 RPM agitation. Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation and the pellet resuspended in 5 mL of infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES-KOH pH 5.7 and 200 μM acetosyringone (#D134406, Sigma-Aldrich). Agrobacterium strains carrying the constructs containing putative interacting proteins were mixed and co-infiltrated in the abaxial surface of four-week-old Nicotiana benthamiana leaves at a final OD600 = 0.5 each. To enhance expression of fusion proteins, Agrobacterium C58C1 carrying the pCH32 helper plasmid that suppress gene silencing [53] was co-infiltrated in all experiments. After 3-4 days, infiltrated regions of Nicotiana leaves were excised and pavement cells visualized in a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510 Meta, Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, U.S.A.) with an argon laser (excitation = 488 nm, emission = 524 nm).

Yeast two-hybrid analysis

Full-length coding regions of bZIP63 (AT5G28770.2) and CHE (AT5G08330.1) were cloned using specific primers (CHE: caccATGGCCGACAACGACGGAGC (FP); TCAACGTGGTTCGTGGTCGTC (RP); bZIP63: caccATGGAAAAAGTTTTCTCCGAC (FP); CTACTGATCCCCAACGCTTC (RP) into pENTR-D-TOPO (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions, to generate pENTR-D-TOPO:bZIP63 and pENTR-D-TOPO:CHE intermediary entry vectors. The sequence indicated in lowercase in the bZIP63 and CHE forward primers (FP) were incorporated by PCR into the amplicon for directional cloning in pENTR-D-TOPO. Subsequently, the intermediary entry vectors were recombined into the yeast expression vectors pDEST32 and pDEST22 of the ProQuest Two-Hybrid System with Gateway Technology (Thermo Scientific) following manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting yeast expression vectors pDEST32:bZIP63; pDEST32:CHE; and pDEST22:bZIP63, as well as the empty vectors pDEST32 and pDEST22 (used here as negative controls) were transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain PJ69-4a (MATa trp1-901 leu2-3,122 ura3-52 his3-200 gal4Δ gal80Δ LYS2::GAL1-HIS3 GAL2-ADE2::GAL7-lacZ) [47]. Y2H assays were performed using yeast double-transformants (pDEST32:bait + pDEST22:prey) lines. The yeast lines obtained were grown for 16 hr (overnight) at 30°C and 200 RPM agitation in minimal SD (Synthetic Defined) liquid medium lacking leucine and tryptophan (SD/-Leu/-Trp), auxotrophic markers for pDEST32 and pDEST22 vector selection, respectively. To verify yeast double transformation, yeast cells carrying the vector combinations shown in the figure were grown in solid SD medium lacking both leucine and tryptophan (SD/-Leu/-Trp. Protein-protein interactions were evaluated by dropping 5 μL of overnight yeast cultures (106 CFU.mL-1) in SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His, where histidine (His) is the auxotrophic marker for protein-protein interaction, and grown at 30°C for 3 days. To reduce background growth due to residual activity of HIS3 gene, 3 mM of 3-Amino-1,2,4-Triazol (3AT), a competitive inhibitor of the HIS3 reporter enzyme, was added to test plates.

Protein isolation and western blotting

Seedling cultivation and sampling occurred as for RNA sampling. Total protein was isolated in 1.1 M glycerol, 5 M Tris-MES (pH 7.6), 1 mM EGTA and 2 mM dithiothreitol with protease inhibitor cocktail P9599 (Sigma). Protein concentrations were quantified with Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad). Proteins were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad), which were subsequently stained with Ponceau Red to verify equal protein loading. Membranes were incubated with KIN10 antiserum (AKIN10/SNF1-related protein kinase catalytic subunit alpha antibody, Agrisera) at 1:1000 dilution with 1% w/v fat-free milk powder and 0.1% v/v Tween 20, and incubated subsequently with goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP conjugate (GtxRb-003-DHRPX from ImmunoReagents, Raleigh, NC) at 1:2000 dilution. Blots were developed using Pierce ECL-2 reagent (Thermo Scientific). Two independent biological repeats were performed of each experiment (data from one repeat shown in Figure S1F).

Transcriptome data meta-analysis

Lists of rhythmic genes and lists of genes that are regulated by KIN10 were compared and their overlaps analyzed for significance. Rhythmic genes were selected from two nycthemeral experiments (light/dark) and three circadian experiments (constant light) [23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. Lists of genes with all the rhythmic transcripts in the nycthemeral experiments or all the circadian genes in the circadian experiments were also analyzed. The KIN10-regulated genes were selected from genes having altered expression in KIN10-ox [17] or in lines overexpressing the E. coli trehalose 6-phosphate synthase (OtsA), which elevates Tre6P in planta [20]. Statistical significance of overlaps and the representation factor were estimated using web-based software designed by Jim Lund (University of Kentucky), with statistical significance quantified using a hypergeometric test [61] (http://elegans.uky.edu/MA/progs/overlap_stats.html). 25% - 40% of transcripts upregulated by KIN10-ox and 19% - 34% of transcripts downregulated by otsA-ox oscillate under light/dark cycles. 49% - 59% of transcripts upregulated by KIN10-ox and 37% - 41% of transcripts downregulated by otsA-ox oscillate under constant conditions. Each overlap was calculated as the proportion of the total number of rhythmic transcripts in each phase bin. Only overlaps with p < 0.01, and representation factor < 0.5 (#) or > 2 (∗) and were considered significant.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Sigmaplot 13.0. Details of statistical tests used, replication levels, and nature of error bars are provided in figure legends. Circadian rhythm parameters were determined using the Biological Rhythms Analysis Software System (BRASS) (University of Edinburgh; millar.bio.ed.ac.uk). Statistical significance of intersections between transcriptomes was calculated with a hypergeometric test [61]. No data were excluded from analysis. Statistical significance is indicated by the p value, where ∗ = p < 0.05, ∗∗ = p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗ = p < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the BBSRC (UK) (grant nos. BB/I005811/1, BB/I005811/2, BB/M006212, and BB/H006826), a RCUK/FAPESP joint research grant, the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) (grant nos. 2008/52071-0 and 2015/06260-0; BIOEN Program), The Royal Society, the Bristol Centre for Agricultural Innovation, the Peter und Traudl Engelhorn-Stiftung, the National Council of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) (Brazil), and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt) (Mexico). We thank Filip Rolland, Ian Graham, Steve Kay, Anthony Hall, and Jose Pruneda-Paz for donating seeds and/or reporter constructs, Ian Graham and Jen Sheen for helpful discussion, and Maeli Melotto (UC Davis) for sharing a Y2H cDNA library.

Author Contributions

A.F., J.K., C.C.M., A.J.C.V., T.J.H., F.E.B., A.Y., D.L.C.-R., A.C., K.C.-B., D.W.N., M.J.H., M.V., A.A.R.W., and A.N.D. designed experiments, collected data, and analyzed data; C.T.H. performed bioinformatics analysis; A.F., C.C.M., M.J.H., C.T.H., M.V., A.A.R.W., and A.N.D. wrote the paper.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: August 2, 2018

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes three figures and one table and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.092.

Contributor Information

Alex A.R. Webb, Email: aarw2@cam.ac.uk.

Antony N. Dodd, Email: antony.dodd@bristol.ac.uk.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Pittendrigh C., Bruce V., Kaus P. On the significance of transients in daily rhythms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1958;44:965–973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.9.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dodd A.N., Dalchau N., Gardner M.J., Baek S.-J., Webb A.A.R. The circadian clock has transient plasticity of period and is required for timing of nocturnal processes in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2014;201:168–179. doi: 10.1111/nph.12489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodd A.N., Salathia N., Hall A., Kévei E., Tóth R., Nagy F., Hibberd J.M., Millar A.J., Webb A.A.R. Plant circadian clocks increase photosynthesis, growth, survival, and competitive advantage. Science. 2005;309:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1115581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang H., Alvarez S., Bindbeutel R., Shen Z., Naldrett M.J., Evans B.S., Briggs S.P., Hicks L.M., Kay S.A., Nusinow D.A. Identification of evening complex associated proteins in Arabidopsis by affinity purification and mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2016;15:201–217. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M115.054064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haydon M.J., Mielczarek O., Robertson F.C., Hubbard K.E., Webb A.A.R. Photosynthetic entrainment of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock. Nature. 2013;502:689–692. doi: 10.1038/nature12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millar A.J. The intracellular dynamics of circadian clocks reach for the light of ecology and evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2016;67:595–618. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-115619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bass J. Circadian topology of metabolism. Nature. 2012;491:348–356. doi: 10.1038/nature11704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solt L.A., Wang Y., Banerjee S., Hughes T., Kojetin D.J., Lundasen T., Shin Y., Liu J., Cameron M.D., Noel R. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by synthetic REV-ERB agonists. Nature. 2012;485:62–68. doi: 10.1038/nature11030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho H., Zhao X., Hatori M., Yu R.T., Barish G.D., Lam M.T., Chong L.-W., DiTacchio L., Atkins A.R., Glass C.K. Regulation of circadian behaviour and metabolism by REV-ERB-α and REV-ERB-β. Nature. 2012;485:123–127. doi: 10.1038/nature11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehlert A., Weltmeier F., Wang X., Mayer C.S., Smeekens S., Vicente-Carbajosa J., Dröge-Laser W. Two-hybrid protein-protein interaction analysis in Arabidopsis protoplasts: establishment of a heterodimerization map of group C and group S bZIP transcription factors. Plant J. 2006;46:890–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mair A., Pedrotti L., Wurzinger B., Anrather D., Simeunovic A., Weiste C., Valerio C., Dietrich K., Kirchler T., Nägele T. SnRK1-triggered switch of bZIP63 dimerization mediates the low-energy response in plants. eLife. 2015;4:4. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weltmeier F., Rahmani F., Ehlert A., Dietrich K., Schütze K., Wang X., Chaban C., Hanson J., Teige M., Harter K. Expression patterns within the Arabidopsis C/S1 bZIP transcription factor network: availability of heterodimerization partners controls gene expression during stress response and development. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;69:107–119. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9410-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nukarinen E., Nägele T., Pedrotti L., Wurzinger B., Mair A., Landgraf R., Börnke F., Hanson J., Teige M., Baena-Gonzalez E. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals the role of the AMPK plant ortholog SnRK1 as a metabolic master regulator under energy deprivation. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:31697. doi: 10.1038/srep31697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin J., Sánchez-Villarreal A., Davis A.M., Du S.X., Berendzen K.W., Koncz C., Ding Z., Li C., Davis S.J. The metabolic sensor AKIN10 modulates the Arabidopsis circadian clock in a light-dependent manner. Plant Cell Environ. 2017;40:997–1008. doi: 10.1111/pce.12903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haydon M.J., Mielczarek O., Frank A., Román Á., Webb A.A.R. Sucrose and ethylene signaling interact to modulate the circadian clock. Plant Physiol. 2017;175:947–958. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirchler T., Briesemeister S., Singer M., Schütze K., Keinath M., Kohlbacher O., Vicente-Carbajosa J., Teige M., Harter K., Chaban C. The role of phosphorylatable serine residues in the DNA-binding domain of Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factors. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2010;89:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baena-González E., Rolland F., Thevelein J.M., Sheen J. A central integrator of transcription networks in plant stress and energy signalling. Nature. 2007;448:938–942. doi: 10.1038/nature06069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matiolli C.C., Tomaz J.P., Duarte G.T., Prado F.M., Del Bem L.E.V., Silveira A.B., Gauer L., Corrêa L.G.G., Drumond R.D., Viana A.J.C. The Arabidopsis bZIP gene AtbZIP63 is a sensitive integrator of transient abscisic acid and glucose signals. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:692–705. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.181743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ezer D., Shepherd S.J.K., Brestovitsky A., Dickinson P., Cortijo S., Charoensawan V., Box M.S., Biswas S., Jaeger K.E., Wigge P.A. The G-Box transcriptional regulatory code in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2017;175:628–640. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y., Primavesi L.F., Jhurreea D., Andralojc P.J., Mitchell R.A.C., Powers S.J., Schluepmann H., Delatte T., Wingler A., Paul M.J. Inhibition of SNF1-related protein kinase1 activity and regulation of metabolic pathways by trehalose-6-phosphate. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:1860–1871. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.133934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Figueroa C.M., Lunn J.E. A tale of two sugars: trehalose 6-phosphate and sucrose. Plant Physiol. 2016;172:7–27. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gómez L.D., Gilday A., Feil R., Lunn J.E., Graham I.A. AtTPS1-mediated trehalose 6-phosphate synthesis is essential for embryogenic and vegetative growth and responsiveness to ABA in germinating seeds and stomatal guard cells. Plant J. 2010;64:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bläsing O.E., Gibon Y., Günther M., Höhne M., Morcuende R., Osuna D., Thimm O., Usadel B., Scheible W.-R., Stitt M. Sugars and circadian regulation make major contributions to the global regulation of diurnal gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3257–3281. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.035261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dodd A.N., Gardner M.J., Hotta C.T., Hubbard K.E., Dalchau N., Love J., Assie J.-M., Robertson F.C., Jakobsen M.K., Gonçalves J. The Arabidopsis circadian clock incorporates a cADPR-based feedback loop. Science. 2007;318:1789–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.1146757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edwards K.D., Anderson P.E., Hall A., Salathia N.S., Locke J.C.W., Lynn J.R., Straume M., Smith J.Q., Millar A.J. FLOWERING LOCUS C mediates natural variation in the high-temperature response of the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2006;18:639–650. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Covington M.F., Harmer S.L. The circadian clock regulates auxin signaling and responses in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith S.M., Fulton D.C., Chia T., Thorneycroft D., Chapple A., Dunstan H., Hylton C., Zeeman S.C., Smith A.M. Diurnal changes in the transcriptome encoding enzymes of starch metabolism provide evidence for both transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of starch metabolism in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:2687–2699. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.044347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y., Gehan J.P., Sharkey T.D. Daylength and circadian effects on starch degradation and maltose metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:2280–2291. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.061903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jakoby M., Weisshaar B., Dröge-Laser W., Vicente-Carbajosa J., Tiedemann J., Kroj T., Parcy F., bZIP Research Group bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:106–111. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(01)02223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruneda-Paz J.L., Breton G., Para A., Kay S.A. A functional genomics approach reveals CHE as a component of the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Science. 2009;323:1481–1485. doi: 10.1126/science.1167206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamichi N., Kiba T., Henriques R., Mizuno T., Chua N.-H., Sakakibara H. PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATORS 9, 7, and 5 are transcriptional repressors in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2010;22:594–605. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kevei E., Gyula P., Fehér B., Tóth R., Viczián A., Kircher S., Rea D., Dorjgotov D., Schäfer E., Millar A.J. Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock is regulated by the small GTPase LIP1. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1456–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalchau N., Baek S.J., Briggs H.M., Robertson F.C., Dodd A.N., Gardner M.J., Stancombe M.A., Haydon M.J., Stan G.-B., Gonçalves J.M., Webb A.A. The circadian oscillator gene GIGANTEA mediates a long-term response of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock to sucrose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:5104–5109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015452108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kang S.G., Price J., Lin P.-C., Hong J.C., Jang J.-C. The arabidopsis bZIP1 transcription factor is involved in sugar signaling, protein networking, and DNA binding. Mol. Plant. 2010;3:361–373. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Para A., Li Y., Marshall-Colón A., Varala K., Francoeur N.J., Moran T.M., Edwards M.B., Hackley C., Bargmann B.O.R., Birnbaum K.D. Hit-and-run transcriptional control by bZIP1 mediates rapid nutrient signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:10371–10376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404657111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trigg S.A., Garza R.M., MacWilliams A., Nery J.R., Bartlett A., Castanon R., Goubil A., Feeney J., O’Malley R., Huang S.-s.C. CrY2H-seq: a massively multiplexed assay for deep-coverage interactome mapping. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:819–825. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giraud E., Ng S., Carrie C., Duncan O., Low J., Lee C.P., Van Aken O., Millar A.H., Murcha M., Whelan J. TCP transcription factors link the regulation of genes encoding mitochondrial proteins with the circadian clock in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3921–3934. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu J.-F., Tsai H.-L., Joanito I., Wu Y.-C., Chang C.-W., Li Y.-H., Wang Y., Hong J.C., Chu J.-W., Hsu C.-P., Wu S.H. LWD-TCP complex activates the morning gene CCA1 in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13181. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kubota A., Ito S., Shim J.S., Johnson R.S., Song Y.H., Breton G., Goralogia G.S., Kwon M.S., Laboy Cintrón D., Koyama T. TCP4-dependent induction of CONSTANS transcription requires GIGANTEA in photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soy J., Leivar P., González-Schain N., Martín G., Diaz C., Sentandreu M., Al-Sady B., Quail P.H., Monte E. Molecular convergence of clock and photosensory pathways through PIF3-TOC1 interaction and co-occupancy of target promoters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:4870–4875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603745113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shor E., Paik I., Kangisser S., Green R., Huq E. PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTORS mediate metabolic control of the circadian system in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2017;215:217–228. doi: 10.1111/nph.14579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pfeiffer A., Shi H., Tepperman J.M., Zhang Y., Quail P.H. Combinatorial complexity in a transcriptionally centered signaling hub in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. 2014;7:1598–1618. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssu087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oh E., Zhu J.-Y., Wang Z.-Y. Interaction between BZR1 and PIF4 integrates brassinosteroid and environmental responses. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:802–809. doi: 10.1038/ncb2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pal S.K., Liput M., Piques M., Ishihara H., Obata T., Martins M.C.M., Sulpice R., van Dongen J.T., Fernie A.R., Yadav U.P. Diurnal changes of polysome loading track sucrose content in the rosette of wild-type arabidopsis and the starchless pgm mutant. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1246–1265. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.212258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seki M., Ohara T., Hearn T.J., Frank A., da Silva V.C.H., Caldana C., Webb A.A.R., Satake A. Adjustment of the Arabidopsis circadian oscillator by sugar signalling dictates the regulation of starch metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:8305. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08325-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ouyang Y., Andersson C.R., Kondo T., Golden S.S., Johnson C.H. Resonating circadian clocks enhance fitness in cyanobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8660–8664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.James P., Halladay J., Craig E.A. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144:1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakamichi N., Kita M., Ito S., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATORS, PRR9, PRR7 and PRR5, together play essential roles close to the circadian clock of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2005;46:686–698. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu X., Hotta C.T., Dodd A.N., Love J., Sharrock R., Lee Y.W., Xie Q., Johnson C.H., Webb A.A.R. Distinct light and clock modulation of cytosolic free Ca2+ oscillations and rhythmic CHLOROPHYLL A/B BINDING PROTEIN2 promoter activity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3474–3490. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.046011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bensmihen S., To A., Lambert G., Kroj T., Giraudat J., Parcy F. Analysis of an activated ABI5 allele using a new selection method for transgenic Arabidopsis seeds. FEBS Lett. 2004;561:127–131. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wesley S.V., Helliwell C.A., Smith N.A., Wang M.B., Rouse D.T., Liu Q., Gooding P.S., Singh S.P., Abbott D., Stoutjesdijk P.A. Construct design for efficient, effective and high-throughput gene silencing in plants. Plant J. 2001;27:581–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walter M., Chaban C., Schütze K., Batistic O., Weckermann K., Näke C., Blazevic D., Grefen C., Schumacher K., Oecking C. Visualization of protein interactions in living plant cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Plant J. 2004;40:428–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Voinnet O., Rivas S., Mestre P., Baulcombe D. An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J. 2003;33:949–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noordally Z.B., Ishii K., Atkins K.A., Wetherill S.J., Kusakina J., Walton E.J., Kato M., Azuma M., Tanaka K., Hanaoka M., Dodd A.N. Circadian control of chloroplast transcription by a nuclear-encoded timing signal. Science. 2013;339:1316–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1230397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gould P.D., Locke J.C.W., Larue C., Southern M.M., Davis S.J., Hanano S., Moyle R., Milich R., Putterill J., Millar A.J., Hall A. The molecular basis of temperature compensation in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1177–1187. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plautz J.D., Straume M., Stanewsky R., Jamison C.F., Brandes C., Dowse H.B., Hall J.C., Kay S.A. Quantitative analysis of Drosophila period gene transcription in living animals. J. Biol. Rhythms. 1997;12:204–217. doi: 10.1177/074873049701200302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haydon M.J., Webb A.A.R. Assessing the impact of photosynthetic sugars on the Arabidopsis circadian clock. In: Duque P., editor. Environmental Responses in Plants: Methods and Protocols. Springer; 2016. pp. 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gendrel A.V., Lippman Z., Yordan C., Colot V., Martienssen R.A. Dependence of heterochromatic histone H3 methylation patterns on the Arabidopsis gene DDM1. Science. 2002;297:1871–1873. doi: 10.1126/science.1074950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng X.Y., Zhou M., Yoo H., Pruneda-Paz J.L., Spivey N.W., Kay S.A., Dong X. Spatial and temporal regulation of biosynthesis of the plant immune signal salicylic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:9166–9173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511182112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Portolés S., Más P. The functional interplay between protein kinase CK2 and CCA1 transcriptional activity is essential for clock temperature compensation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim S.K., Lund J., Kiraly M., Duke K., Jiang M., Stuart J.M., Eizinger A., Wylie B.N., Davidson G.S. A gene expression map for Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;293:2087–2092. doi: 10.1126/science.1061603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.