Abstract

A few commonly used non-antibiotic drugs have recently been associated with changes in gut microbiome composition, but the extent of this phenomenon is unknown. We screened >1000 marketed drugs against 40 representative gut bacterial strains, and found that 24% of the drugs with human targets, including members of all therapeutic classes, inhibited the growth of at least one strain. Particular classes such as the chemically diverse antipsychotics were overrepresented. The effects of human-targeted drugs on gut bacteria are reflected on their antibiotic-like side effects in humans and are concordant with existing human cohort studies, providing in vivo relevance for our screen. Susceptibility to antibiotics and human-targeted drugs correlates across bacterial species, suggesting that non-antibiotics may promote antibiotic resistance. Our results provide a comprehensive resource for future research on drug-microbiome interactions, opening new paths for side effect control and drug repurposing, and broaden our view on antibiotic resistance.

Introduction

Pharmaceuticals have both beneficial and undesirable effects. Improving their efficacy and reducing their side effects are the focus of studies on the mechanism of action (MoA) and off-target spectrum of various drugs. Yet, the role of the gut microbiota on both these levels is rarely considered, even though gastrointestinal side effects are common for drugs and the gut microbiome itself is pivotal for human health 1. Recently, consumption of drugs designed to target human cells and not microbes, such as antidiabetics (metformin 2), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) 3,4, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs 5 and atypical antipsychotics (AAPs) 6, was associated with microbiome composition changes. A larger cohort study implied a more general role of medication on gut microbiome composition 7. As it is unclear whether such effects are direct and go beyond the few drug classes studied, we systematically profiled interactions between drugs and individual gut bacteria. We aimed at generating a comprehensive resource of drug action on the microbiome, which could nucleate more in-depth clinical and mechanistic studies, ultimately improving therapy and drug design.

Results

A high-throughput drug screen on human gut bacterial species

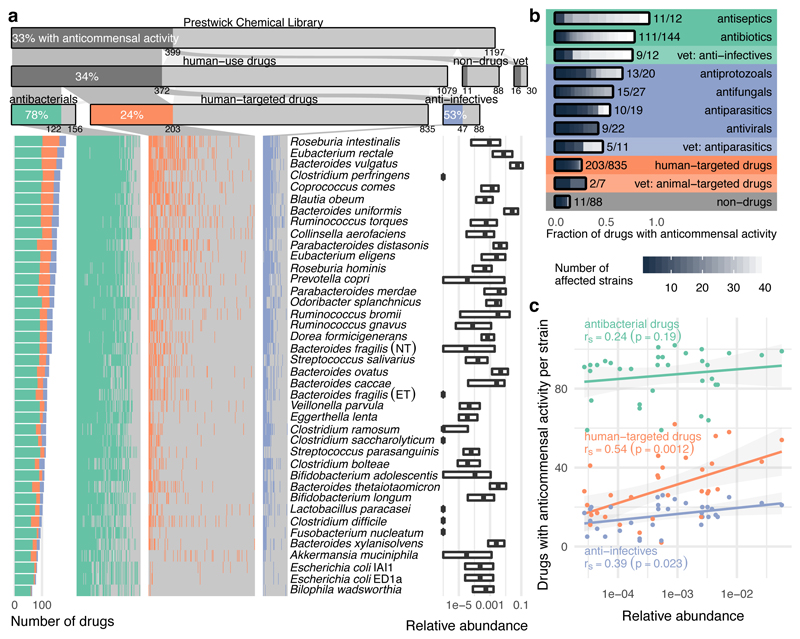

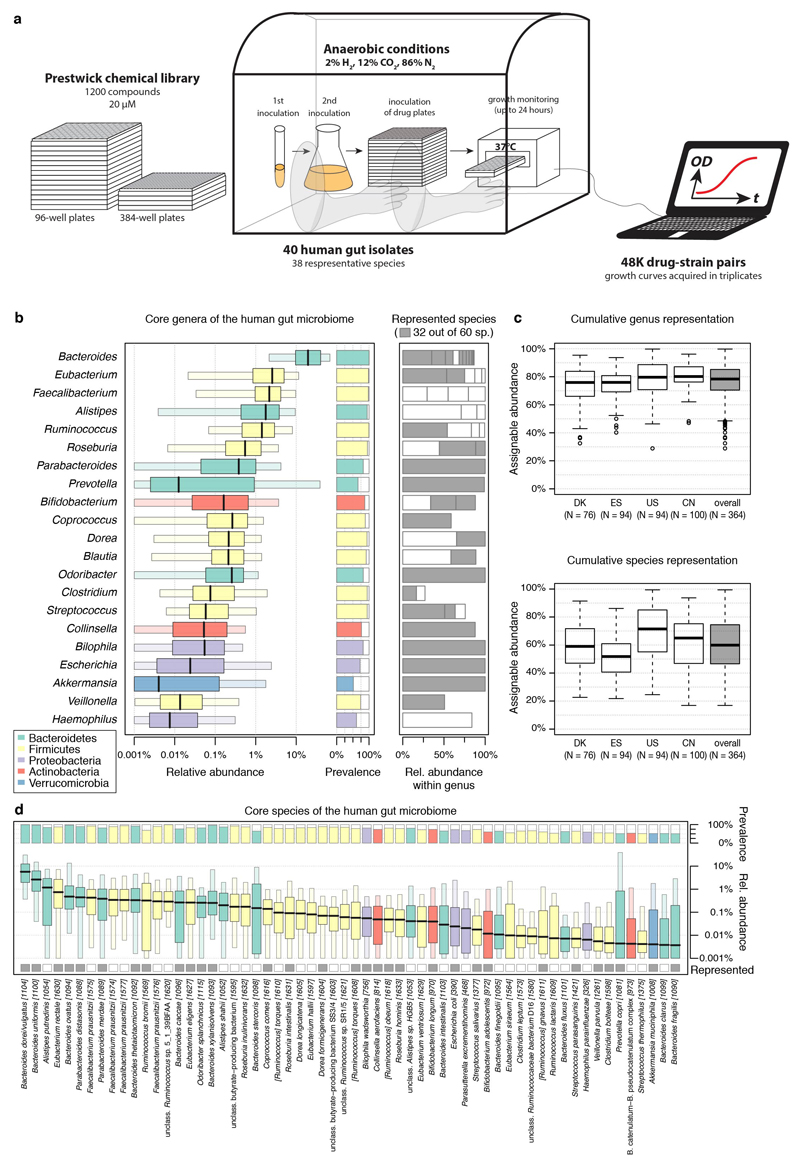

To systematically map interactions between drugs and human gut bacteria, we monitored the growth of 40 representative isolates upon treatment with 1197 compounds in modified Gifu Anaerobic Medium broth (mGAM), which partially recapitulates relative gut microbiota abundances 8, under anaerobic atmosphere, at 37°C (ED Fig. 1a). We used the Prestwick Chemical Library, consisting mostly of off-patent FDA-approved compounds with high chemical and pharmacological diversity. Most compounds are administered to humans (1079), covering all main therapeutic classes (Supplementary Table 1). Three quarters (835) are human-targeted drugs (i.e. have molecular targets in human cells), whereas the rest are anti-infectives: 156 with antibacterial activity (144 antibiotics, 12 antiseptics) and 88 effective against fungi, viruses or parasites (Fig. 1a). All compounds were screened at 20 μM, which is within range of what is commonly used in high-throughput drug screens 9.

Figure 1. Systematic profiling of marketed drugs on a representative panel of human gut microbial species.

a. Broad impact of pharmaceuticals on the human gut microbiota. Compounds of the Prestwick Chemical Library are divided into drugs used in humans, exclusively in animals (veterinary) and compounds without medical/veterinary use (non-drugs). Human-use drugs are further categorized according to targeted organism. Strain-drug pairs (i.e. instances when a drug significantly reduced the growth of a specific strain; Methods) are highlighted with a vertical colored bar in the matrix. Bacterial strains are sorted by drug sensitivity. Relative abundances of each strain in four cohort studies of healthy individuals are displayed on the right (boxes correspond to IQR and central line to median relative abundance). b. Fraction of drugs with anticommensal activity by sub-category. Grey scale within bars denotes inhibition spectrum, that is the number of affected strains per drug. c. Correlation between species abundance in the human microbiome and their drug sensitivity. For each strain (N=40), the number of drugs impacting its growth is plotted against its median relative abundance in the human gut microbiome. Lines depict the best linear fit, rS the Spearman correlation and grey shade the 95% confidence interval of the linear fit. All drugs, and in particular human-targeted drugs inhibit the growth of abundant species more.

To be representative of the gut microbiome of healthy individuals we selected a set of ubiquitous gut bacterial species (Supplementary Table 2). Prevalence and abundance in the human gut, and phylogenetic diversity were our main selection criteria (ED Fig. 1b), although we were occasionally constrained by strain unavailability or irreproducible growth in mGAM. In total, we included 40 human gut isolates from 38 bacterial species and 21 genera (Escherichia coli and Bacteroides fragilis are represented by two strains), accounting together for 78% of the median assignable relative abundance of the human gut microbiome at genus level (60% at species level, ED Fig. 1c). Most strains are commensals, covering 31/60 sequenced species detected at a relative abundance of ≥1% and prevalence of ≥50% in fecal samples of asymptomatic humans from three continents (ED Fig. 1d). In addition, the set includes four pathobionts (Clostridium difficile, Clostridium perfringens, Fusobacterium nucleatum and an enterotoxigenic strain of B. fragilis), a probiotic (Lactobacillus paracasei) and two commensal Clostridia (C. ramosum and C. saccharolyticum). All 38 species are found in the gut of healthy individuals and are part of a larger strain resource panel for the healthy human gut microbiome 8.

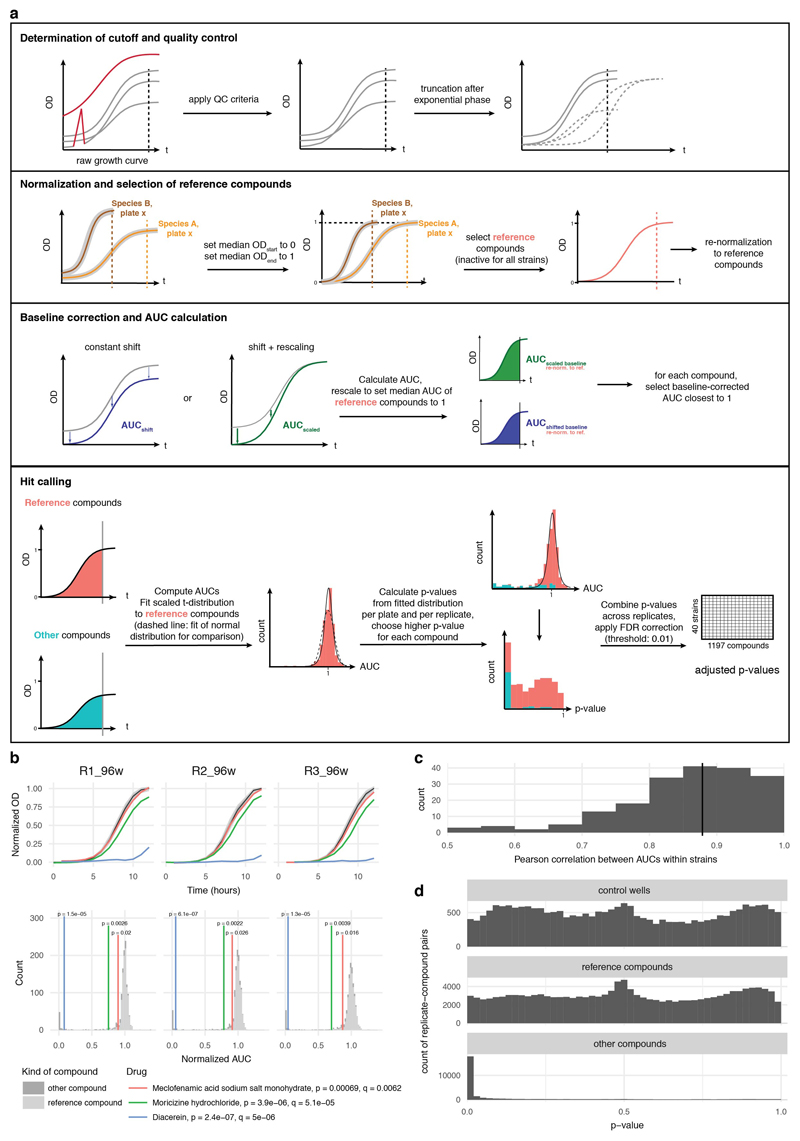

We screened all compounds in multi-well plates, measuring optical density over time to monitor growth, and quantifying the area under the growth curve (AUC) up to the timepoint at which controls with unperturbed growth transitioned to stationary phase (Methods & ED Fig. 2). We obtained at least three biological replicates per strain, which highly correlated (ED Fig. 2c). We then tested for significant deviations from the normalized AUC distribution of samples with unperturbed growth, combining p-values across replicates and correcting for multiple hypothesis testing on the complete matrix of compounds and strains (Methods and ED Fig. 2). Drugs significantly reducing growth of at least one strain (FDR < 0.01), were classified as hits with anticommensal activity (Supplementary Table 3a), reflecting their potential to modulate the human gut microbiota.

Of the 156 antibacterials tested, 78% were active against at least one species, typically with broad activity spectrum (Fig. 1a-b). Inactive antibiotics mainly belong to sulfonamides (inactive in our media; manufacturer’s guidelines), aminoglycosides (compromised activity under anaerobic conditions 10) and specific antimycobacterial drugs. Antibiotics are used to inhibit pathogens, but as expected, also target gut commensals. The medical importance of this collateral damage to the resident microbiome is lately becoming clearer 11. Nevertheless, drug-microbiome species relationships had not been mapped at this scale before.

Interestingly, 27% of the non-antibiotic drugs were also active in our screen. More than half of the anti-infectives against viruses or eukaryotes exhibited anticommensal activity (47 drugs; Fig. 1 a-b). Antibacterial activity has been previously reported for many, including the antifungal imidazoles 12 (11 in our screen), but for others (e.g. the antivirals saquinavir and trifluridine) such activity is new. More noteworthy is the anticommensal activity of 203 (24%) human-targeted drugs. Most were effective against smaller subsets of strains with the exception of 40 drugs that affected at least 10 strains – 14 with no previously reported direct antibacterial activity (Supplementary Table 3b). Among the known ones, auranofin was recently reported to have broad-spectrum bactericidal activity 13, and the ovulation stimulant clomiphene inhibits a conserved bacterial enzyme in the synthesis of an essential precursor for cell wall carbohydrate polymers 14. Such drugs or their scaffolds can be used for repurposing towards antibiotics, especially since many have MICs reaching the sub μg/ml range (Supplementary Table 4). In contrast, the microbial specificity of most human-targeted drugs could aid the development of microbiome modulators.

Species responded to drugs variably with the abundant Roseburia intestinalis, Eubacterium rectale and Bacteroides vulgatus being the most sensitive, and γ-proteobacteria representatives being the most resistant (Fig. 1a). Overall, species with higher relative abundance across healthy individuals were significantly more susceptible to human-targeted drugs (Fig. 1c). This suggests that human-targeted drugs have an even larger impact to the gut microbiome with key species related to healthy status 15, such as major butyrate- (E. rectale, R. intestinalis, Coprococcus comes) and propionate-producers (B. vulgatus, Prevotella copri, Blautia obeum) 16, and enterotype drivers (P. copri) 17 taking the heavier toll.

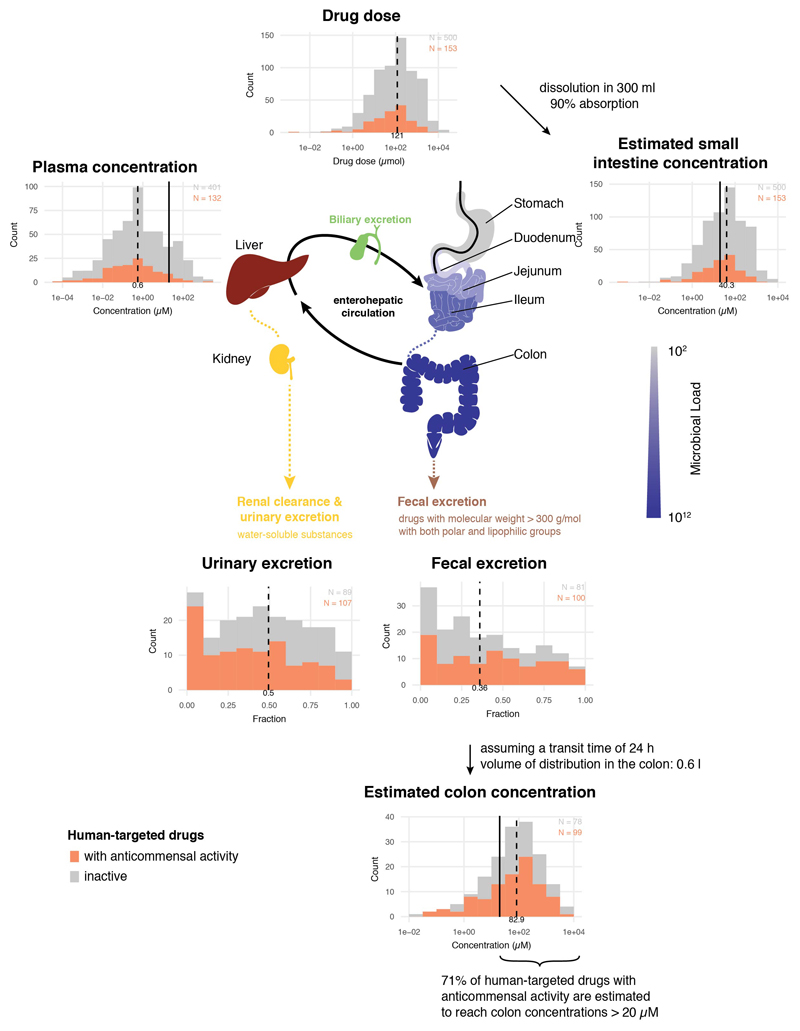

Dose relevance and validation of the in vitro drug screen

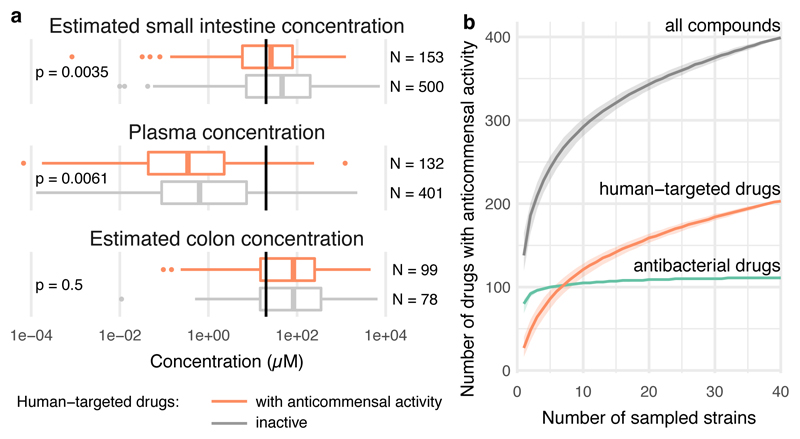

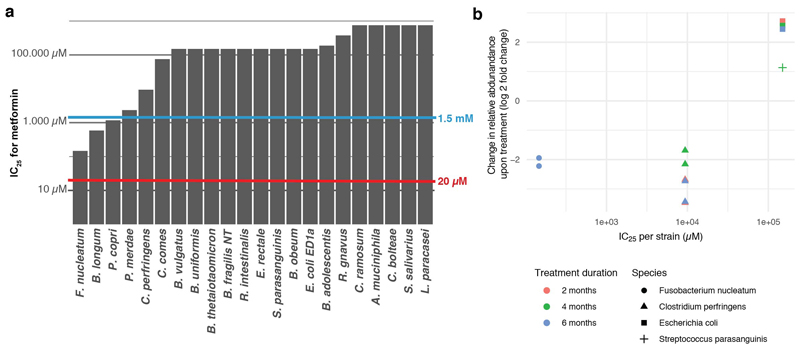

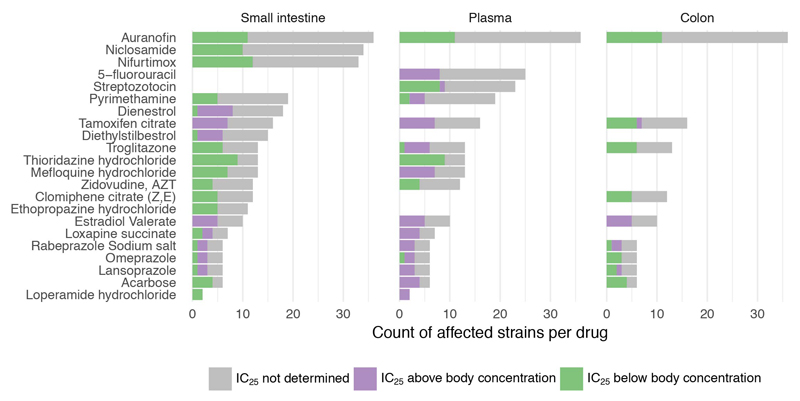

We sought to address how close the screening concentration (20 μM) is to drug concentrations in the terminal ileum and colon, where most gut microbes reside 18. However, drug concentrations are systematically measured only in blood; there human-targeted drugs have on average an order of magnitude lower concentrations than in our screen (Fig. 2a & ED Fig. 3). We deduced colon concentrations based on drug excretion patterns from literature, and small intestine concentrations based on daily doses of individual drugs (Supplementary Table 1) and a measured example of duodenal concentrations for the well-absorbed drug posaconazole 19 (Methods). Based on these approximations, 20 μM was below the median small intestine and colon concentration of the human-targeted drugs tested here (Fig. 2a, ED Fig. 3). Interestingly, human-targeted drugs with anticommensal activity have lower plasma and estimated small intestinal concentrations than ones without (Fig. 2a; p = 0.0061 and p = 0.0035, respectively, two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test; we have fewer colon concentration estimates due to data availability), suggesting that more human-targeted drugs would inhibit bacterial growth if probed at higher doses, closer to physiological concentrations. A case in point is metformin, which was recently identified as the key contributor to changes in the human gut microbiome composition of type-II diabetes (T2D) patients 2, but lacked anticommensal activity in our screen. Metformin reaches 10-40 μM in the plasma of treated T2D patients, but its small intestine concentration is 30-300 fold higher 20, which matches our small intestine and colon concentration estimates (1.5 mM). When we probed for higher, more physiological intestinal metformin concentrations, 3 of 22 tested strains were inhibited at concentrations below 1.5 mM (ED Fig. 4a).

Figure 2. Evaluating human-targeted drugs with anticommensal activity.

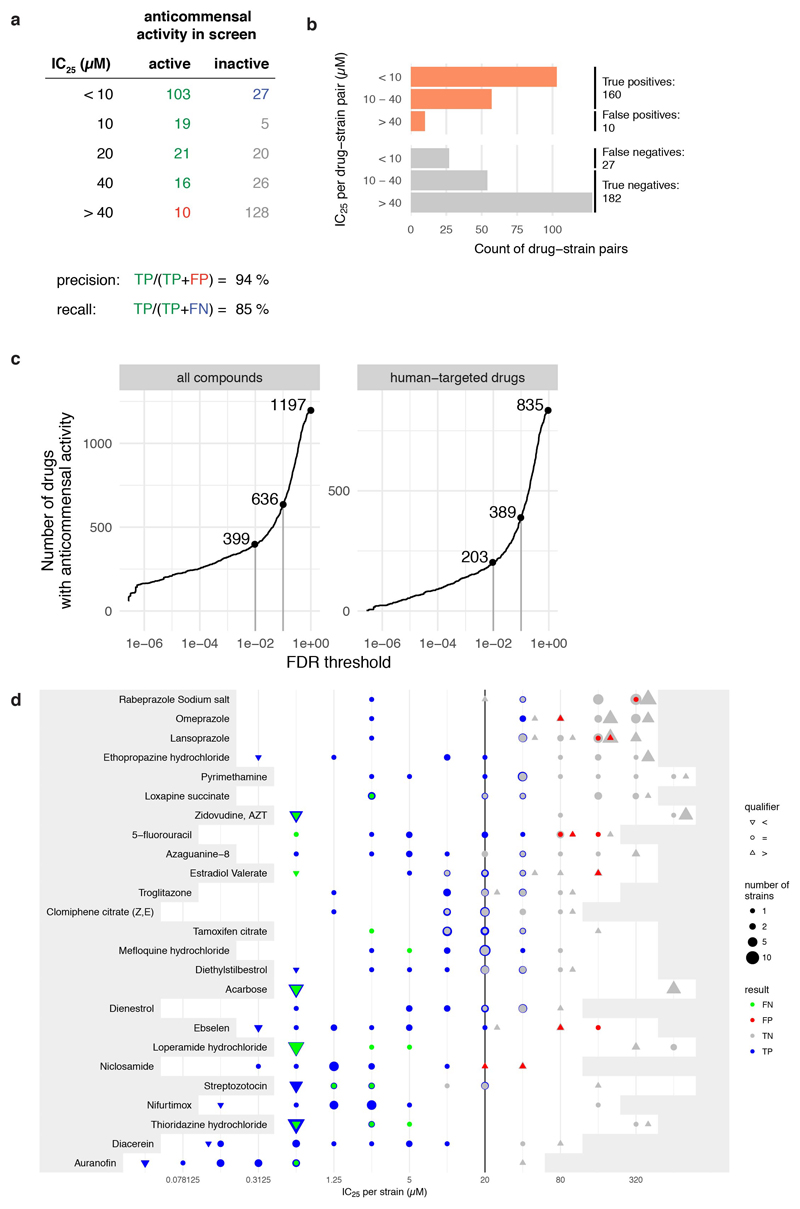

a. Estimated small intestine and colon concentrations, and measured plasma concentrations for human-targeted drugs with (orange) and without (grey) anticommensal activity in our screen (Methods, ED Fig. 2). For both active and inactive compounds, the median estimated small intestine and colon concentrations are higher than the screened concentration (20 μM, black vertical lines), whereas plasma concentrations are lower. Non-hits in our screen generally reach higher plasma and small intestine concentrations (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test). Box plots: center line, median; limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x IQR; points, outliers. b. Rarefaction analysis indicates that anticommensal activity would be discovered for more human-targeted drugs if we screened additional strains.

We also benchmarked our screen with an independent set of experiments, measuring IC25 (the drug concentration conferring 25% growth inhibition) for 25 selected drugs in a subset of up to 27 strains (Methods). This analysis revealed excellent precision (94%), but slightly lower recall (85%) (ED Fig. 5a-b). False negatives, i.e. drugs with anticommensal activity missed in our screen, were due to specific chemicals that likely lost activity during screening (ED Fig. 5d), and our stringent FDR cutoff for calling hits. Increasing this cutoff to 0.1 would almost double the fraction of drugs with anticommensal activity (ED Fig. 5c). In addition, we found that more species were inhibited at higher concentrations (ED Fig. 5d & Supplementary Table 4), and that IC25’s were mainly below the estimated gut concentrations and occasionally below plasma concentrations (ED Fig. 6).

Furthermore, we only screened a representative subset of species, but the gut microbiome of an individual harbors hundreds of species and an even larger strain diversity 21. Rarefaction analysis indicates that if more gut species were tested, the fraction of human-targeted drugs with anticommensal activity would increase (Fig. 2c).

In summary, we probed human-targeted drugs largely within physiologically relevant concentrations and we likely underreport the impact of human-targeted drugs in gut bacteria.

Concordance with clinical studies and side effect patterns support physiological relevance

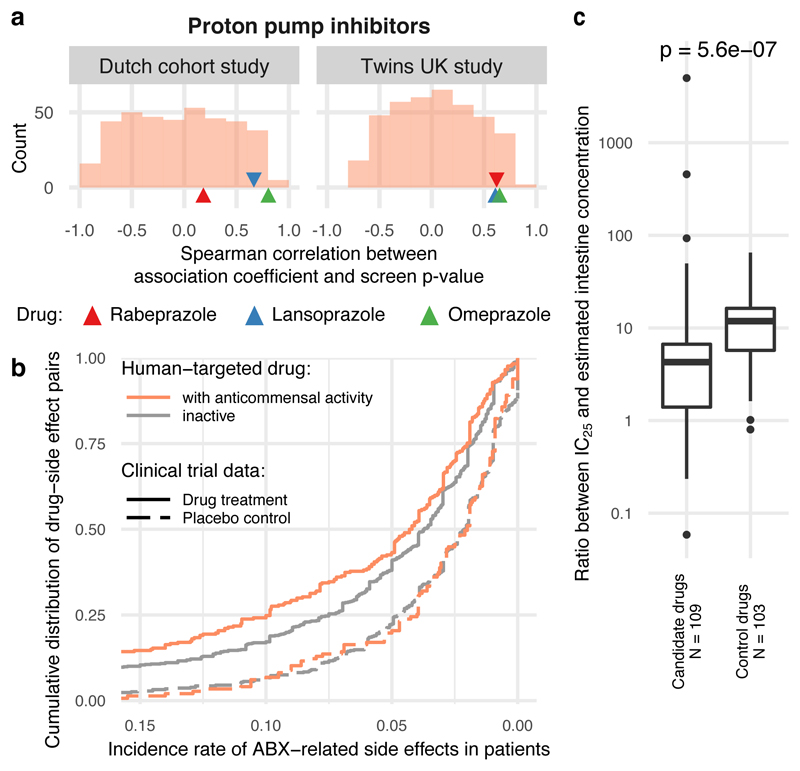

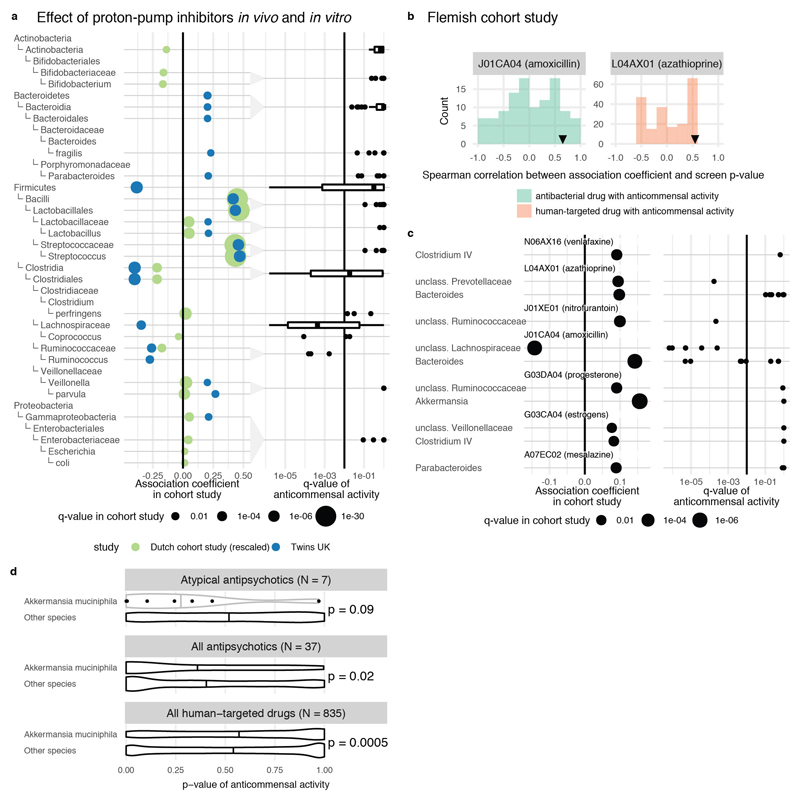

Having demonstrated that many human-targeted drugs inhibit gut bacteria in vitro at relevant doses, we searched for evidence that such effects manifest in vivo in the human gut. We reviewed all available clinical cohort data from metagenomics association studies and compared it to our screen if studies had enough statistical power and affected taxa overlapped with those tested here. We found suitable studies for PPIs, AAPs, and 7 further drugs, spanning altogether 5 different drug classes according to Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification. All three PPI representatives in our screen exhibited broad anticommensal activity similar to microbiome changes occurring in patients taking PPIs 3,4 (Fig. 3a): taxa with reduced abundance in patients exhibited reduced growth in our screen and enriched taxa in patients were rarely inhibited by PPIs in vitro (ED Fig. 7a). This suggests that PPIs directly influence the gut microbiome composition, in addition to changing the stomach pH and thus, which bacteria reach the gut 3,4. Concordance was similarly high for many microbe-drug associations identified in a large Flemish cohort 7 for the immunosuppressive azathioprine, the antidepressant venlafaxine, the anti-inflammatory mesalazine, aminosalicylate, progesterone, estrogens and amoxicillin; the only exception was another antibiotic, nitrofurantoin (ED Fig. 7b-c). We also compared our data to a study reporting lower Akkermansia levels after treatment with AAPs 6. Our screen included 6/10 AAPs investigated in this study. Akkermansia muciniphila was significantly more sensitive to these AAPs than other strains (p = 0.09; one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test), while being more resistant to other human-targeted drugs (p = 0.0005, one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test; ED Fig. 7d). Finally, we found high concordance between a longitudinal microbiome study of patients taking metformin and our IC25 data for the same drug (ED Fig. 4b).

Figure 3. Anticommensal activity of human-targeted drugs in vitro reflects patient data.

a. Changes in microbiome composition of patients taking PPIs are in agreement with drug effects in our screen. Displayed are Spearman correlation coefficients between in vitro growth inhibition p-values and changes in taxonomic relative abundances after PPI consumption for corresponding taxa from two studies (Twins UK 4 and Dutch 3 cohorts, 229/1827 and 211/1815 individuals had taken PPIs respectively). The histogram represents the background distribution of correlations between the in vitro data for all human-targeted drugs and the in vivo response to PPIs; correlations with PPIs are highlighted by triangles. b. Human-targeted drugs with anticommensal activity in our screen had a significantly higher incidence of antibiotic-related side effects (orange trace shows cumulative distribution, N = 285 drug-side effect pairs) in clinical trials compared to drugs without activity (grey trace, N = 767; p = 0.002, two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test). Dashed lines indicate the incidence of the same side effects upon placebo treatment, with no significant difference between active (N = 138) and inactive drugs (N = 474). c. Based on similarity to antibiotic-related side effects, we selected 26 candidate and 16 control drugs for testing for anticommensal activity. Although both candidate and control drugs inhibited bacterial growth at higher concentrations, candidate drugs had anticommensal activity at significantly lower doses than control drugs (p = 5.6e-7, two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test). Box plots as in Fig. 2a.

Metagenomics association studies and our in vitro study have distinct limitations. We screened a subset of species, mostly one strain per species, out of the context of microbial communities and the host. Cohort studies can be underpowered, biased by methodological approaches and confounding factors, and may detect indirect effects. Nonetheless, we find high concordance between effects of drugs in vitro and in humans, confirming the clinical relevance and direct anticommensal activities for the aforementioned cases.

To further assess the physiological relevance of our screen, we investigated the registered side effects of these drugs in humans. We first identified side effects enriched in antibiotics for systemic use compared to those found in all other drugs in the SIDER database 22. We identified 69 side effects, which were enriched in antibiotics (Methods, Supplementary Table 5). These antibiotic-related side effects occurred with higher frequency in clinical trials for human-targeted drugs with anticommensal activity compared to inactive compounds in our screen (p = 0.002, two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test), whereas no significant difference was observed for placebo-treated patients (Fig. 3b). This suggests that the collateral damage of human-targeted drugs on gut bacteria can be detected by higher occurrences of antibiotic-like side effects in patients.

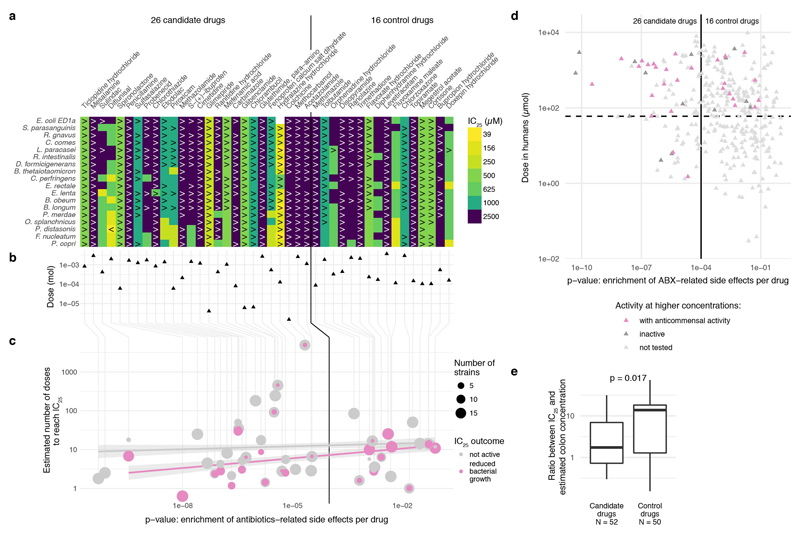

We then tested whether this side effect signature was predictive of anticommensal activity of human-targeted drugs, which we may have missed due to the low drug concentration we used. We screened 26 candidate compounds with enrichment of antibiotic-related side effects and 16 without (control compounds) in 18 strains (ED Fig. 8), in concentrations up to 2.5 mM (Methods). 28/42 compounds inhibited the growth of at least one strain (ED Fig. 8), with both the fraction of active compounds and the number of affected strains being similar for both candidate and control compounds. However, when we normalized the measured IC25 by the recommended drug dose to make amounts comparable between drugs, a significant difference was evident. Drugs predicted to be active had a median IC25 across all drug–strain pairs that corresponded to 4.3 drug doses, compared to 12 for control drugs (p = 2e-6, one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test; Fig. 3c). The IC25 corresponds to less than two drug doses in 34% of drugs with predicted activity, compared to just 8% for control drugs. Similarly, the IC25 is below the estimated colon concentration for 16/52 (31%) of candidate drugs and only for 5/50 (10%) of control drugs (ED Fig. 8e).

In conclusion, human-targeted drugs with anticommensal activity have antibiotic-like side effects in humans, and for the few studies available, consumption of these drugs led to changes in taxa we also detected to be inhibited in vitro, implying that more drugs with anticommensal activity reported here will have an impact in vivo.

Features of human-targeted drugs with anticommensal activity

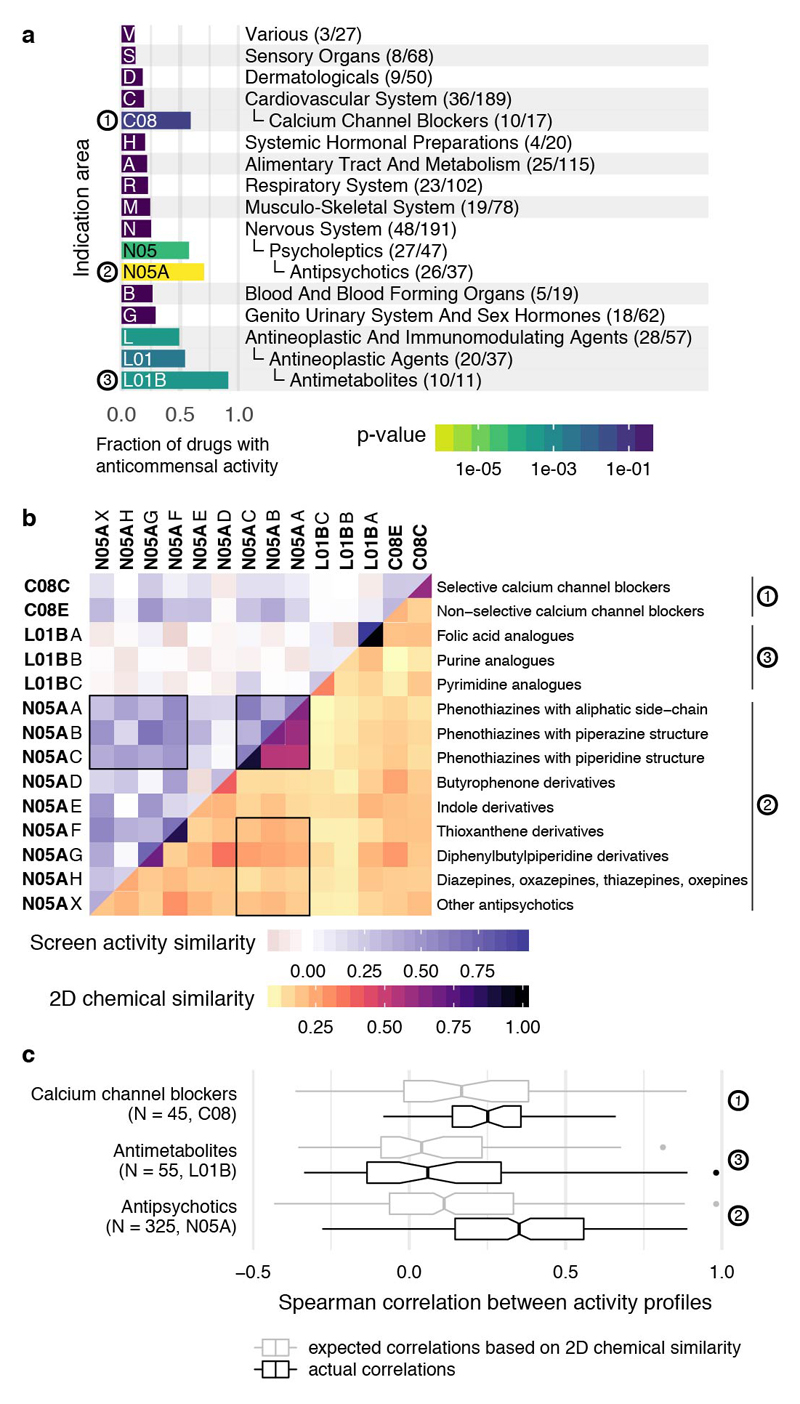

Drugs from all major ATC indication areas exhibited anticommensal activity, with antineoplastics, hormones and compounds targeting the nervous system inhibiting gut bacteria more than other medications (ED Fig. 9a & 10). Three ATC subclasses were significantly enriched in hits: antimetabolites, antipsychotics and calcium-channel blockers (ED Fig. 9a). Antimetabolites are used as chemotherapeutic and immunosuppressant agents with their incorporation into RNA/DNA or their interaction with respective synthesis enzymes being cytotoxic to human cells. Their molecular targets are often conserved in bacteria 23, explaining the observed effects and raising the possibility that antibacterial effects may also be directly involved in mucositis development during chemotherapy 24.

The enrichment in antipsychotics is intriguing, given that they target dopamine and serotonin receptors in the brain, which are absent in bacteria. Although phenothiazines are known to have antibacterial effects 25, nearly all subclasses of the chemically diverse antipsychotics exhibited anticommensal activity (ED Fig. 9b). They targeted a significantly more similar pattern of species than expected from their chemical similarity (ED Fig. 9b-c). This raises the possibility that direct bacterial inhibition may not only manifest as side effect for antipsychotics 26, but also be part of their MoA.

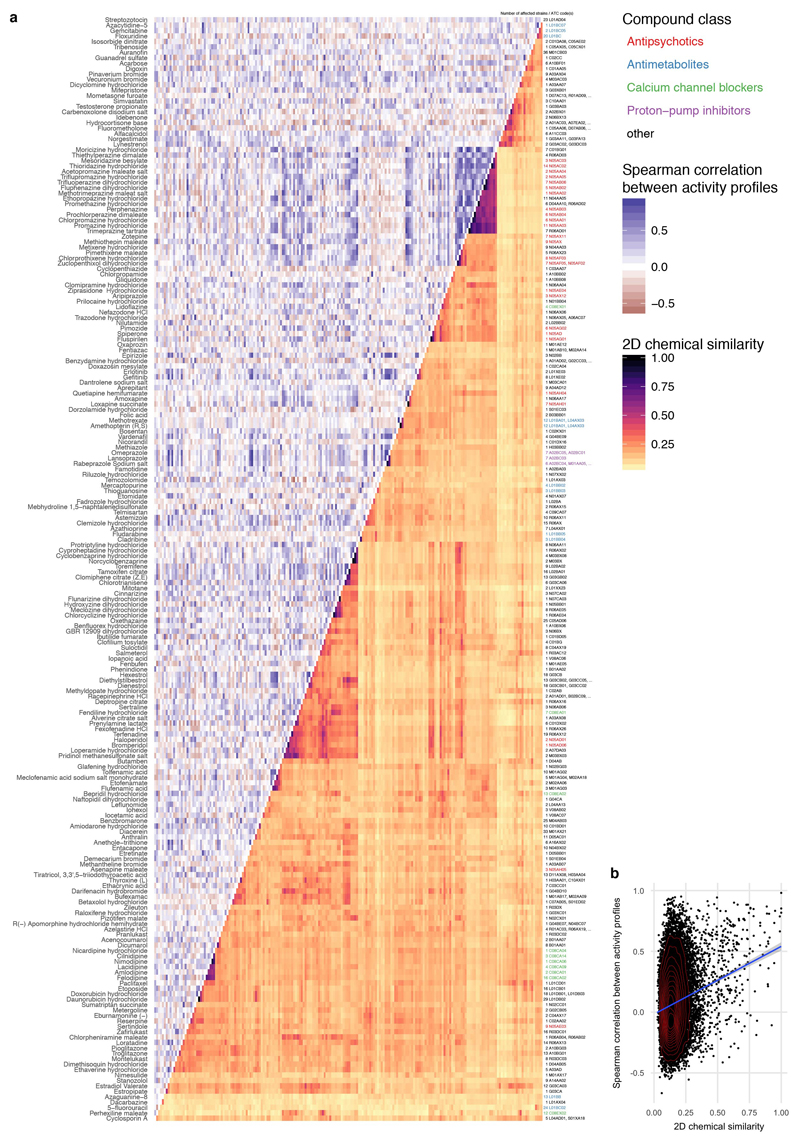

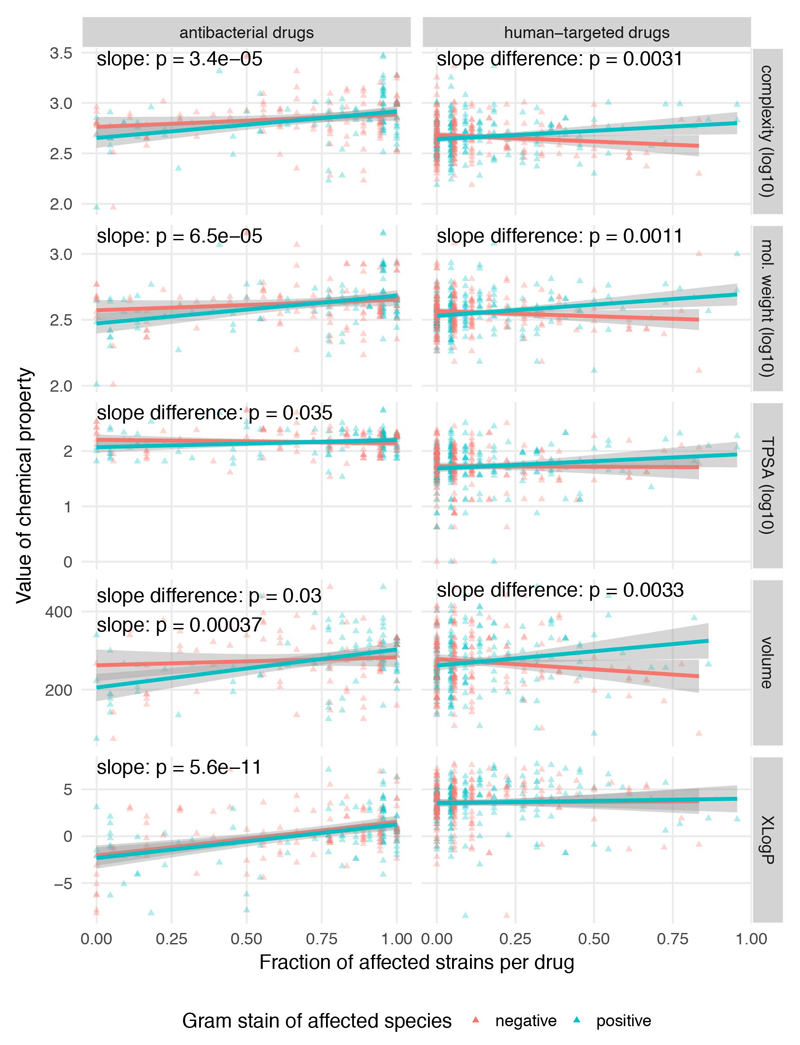

As different indication areas contain chemically similar drugs, we explored whether chemical properties of drugs can influence their anticommensal activity (ED Fig. 11a). To some degree, chemically similar human-targeted drugs had more similar effects in the screen (ED Fig. 11b). We tested several compound properties including complexity, molecular weight, topological polar surface area (TPSA), volume and hydrophobicity (XLogP). Complex, heavier and larger compounds preferentially targeted Gram-positive bacteria, whereas Gram-negative bacteria were protected against such bulkier drugs by their selective outer membrane barrier (ED Fig. 12). Due to the vast number of chemical moieties present in drugs with anticommensal activity, we did not attempt an exhaustive enrichment analysis. Nevertheless, we did observe reactive nitro-groups being enriched in drugs with anticommensal activity (p=6.4 e-06, Fisher’s exact test), indicating that local chemical properties may confer antibacterial activity.

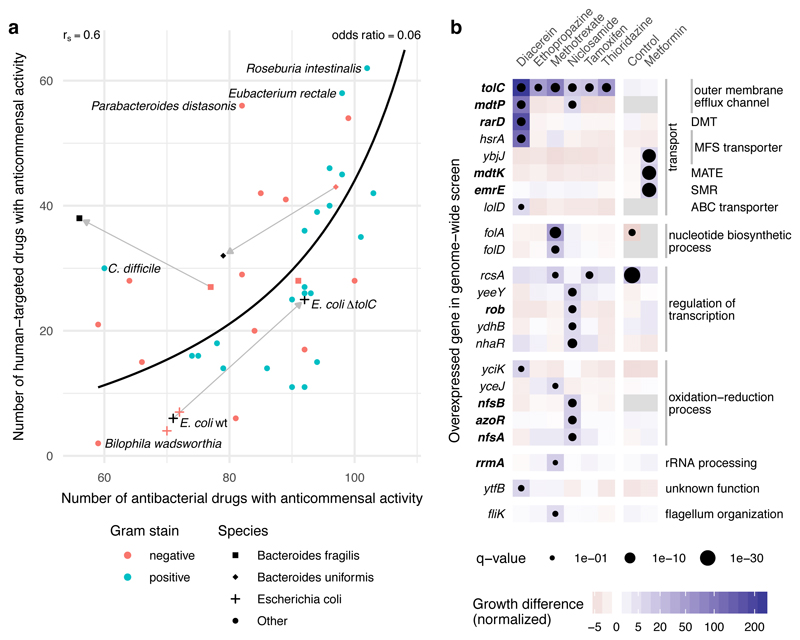

Human-targeted drug consumption may promote antibiotic resistance

There is a strong correlation between resistance to antibacterials and human-targeted drugs in our data, not simply explained by general cell envelope composition, as there is no clear division between Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Fig. 4a). We reasoned that more specific, yet common mechanisms could confer resistance against both drug groups. To test this hypothesis, we selected TolC, known to efflux several antibiotics in E. coli and other bacteria 27, as a prominent representative of a common resistance mechanism against antibiotics. We profiled an E. coli ΔtolC mutant and its parental wildtype (BW25113) against the Prestwick Chemical Library. E. coli lacking TolC did not only become more sensitive to antibacterials (22 hits more than wildtype), but also became equally more sensitive to human-targeted drugs (19 additional hits; Fig. 4a & Supplementary Table 6). This effect is not E. coli- or TolC-specific, since a more antibiotic-resistant B. uniformis strain (HM-715) was also equally more resistant to human-targeted drugs (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4. Antibiotic resistance mechanisms protect against human-targeted drugs.

a. Susceptibility to antibacterials and human-targeted drugs correlates across the 40 tested strains (Spearman correlation, rS=0.6 and a line depicting the nonlinear least-squares estimate of the odds ratio, OR=0.06), suggesting common resistance mechanisms against both drug types. Knocking out a major antibiotic efflux pump, tolC, in the lab E. coli strain, BW25113 (behaving as the other 2 commensal E. coli strains in the screen), makes E. coli equally more sensitive to both antibacterials and human-targeted drugs. Two antibiotic-resistant isolates of B. fragilis (black square, HM-20) and B. uniformis (black diamond, HM-715) were screened in addition to the main screen with only the latter showing a similar increase in resistance towards human-targeted drugs. b. Chemical genetic screen of an E. coli genome-wide overexpression library in 7 non-antibiotics; all screens except for metformin were performed in ΔtolC background to sensitize E. coli to these drugs. Genes that when overexpressed improved significantly the growth of E. coli to at least one of the drugs are shown here; in bold genes previously associated with antibiotic resistance. Among them, genes encoding for transporters from different families: DMT (drug metabolite transporter), MFS (major facilitator superfamily), MATE (multidrug and toxin extrusion), SMR (small multidrug resistance) and ABC (ATP-binding cassette). Growth is measured by colony size (median n=4) 41, color depicts the normalized size difference from the median growth of all strains in the drug (>6-fold difference), and dot size the significance (FDR-corrected p-value <0.1). Control denotes the growth of the library without drug.

While our data support a strong role for general resistance mechanisms, there are also outliers to this trend, the most prominent being C. difficile and P. distansonis (Fig. 4a). For both previously known, strong antibiotic resistance 28 was contrasted with relatively weaker resistance to human-targeted drugs. Similarly, an antibiotic-resistant B. fragilis strain, HM-20, was not equally resistant against human targeted drugs (Fig. 4a). These examples make the important distinction between specific antibiotic resistance mechanisms, irrelevant for resistance to human-targeted drugs, and more predominant, general mechanisms, which confer resistance to both drug groups.

To more systematically elucidate mechanisms conferring resistance against human-targeted drugs, we employed a chemical genetic approach 29 and screened a genome-wide overexpression library in E. coli against seven non-antibiotics (six human-targeted drugs and niclosamide, an antiparasitic) with broad anticommensal activity in our screen. Since wildtype E. coli was one of the most resistant gut species (Fig. 4a), we used the ΔtolC mutant, which is sensitive to most of these drugs, allowing us to probe further resistance mechanisms. For all tested drugs except metformin, overexpression of tolC rescued E. coli growth, as expected. Furthermore, we identified a number of diverse transporter families contributing to resistance against these drugs (Fig. 4b). Many of them have previously been linked to antibiotic resistance 30–33. Resistance was also acquired by overexpression of transcription factors (e.g. rob controlling efflux pump expression 34), the ribosome maturation factor rrmA, which plays a role in resistance to the antibiotic viomycin 35, and detoxification mechanisms (nitroreductases modify nitro-containing antibiotics 36). For methotrexate, we validated the known primary target in bacteria (E. coli dihydrofolate reductase) 37, illustrating the potential of this approach to identify bacterial MoA of human-targeted drugs 29.

All these results point to an overlap between resistance mechanisms against antibiotics and human-targeted drugs, implying a hitherto unnoticed risk of acquiring antibiotic resistance by consuming non-antibiotic drugs.

Discussion

We report the first systematic drug screen against a reference panel of human gut bacteria. 27% of non-antibiotics (24% of human-targeted drugs) inhibited the growth of at least one species. As we demonstrated, this is likely an underestimate due to stringent thresholds for calling hits and the limited selection of bacterial strains screened. Many of the direct in vitro effects described here may translate into microbiome shifts in vivo, since (i) we used concentrations within range of what is estimated to be found in the human gut for many drugs, (ii) our observations agree with the few clinical microbiome studies for which medication has been recorded, and (iii) side effects of anticommensal drugs in humans resemble those of antibiotics. Thus, our results underscore the necessity of accounting for potential medication-related confounding effects in future microbiome disease association studies. Taking into account that abundant members of the human gut microbiome are impacted more by drugs, one could speculate that pharmaceuticals, used regularly in our times, may be contributing to the decrease in the diversity of microbiomes of modern Western societies 38.

Although the antibacterial potential of human-targeted drugs has been profiled repeatedly in the quest for new antimicrobials, previous efforts focused on pathogenic and often multi-drug-resistant (MDR) species 9,13,14. We demonstrate that some of these species or their commensal relatives are the most resistant in our screen (e.g. γ-proteobacteria: Bilophila wadsworthia and E. coli were impacted by 2 and 4-7 human targeted drugs, respectively), that many human-targeted drugs have species-specific effects, and that resistance mechanisms to antibiotics and human-targeted drugs partially overlap (thus, MDR species may be more resistant to human drugs too). Altogether these findings explain why previous efforts failed to register how many human-targeted drugs can inhibit bacteria.

We show that many pharmaceuticals influence the human gut microbiota. As gut bacteria, in turn, can also modulate drug efficacy and toxicity 39, the emerging drug-microbe network could guide therapy and drug development. The herein described resource already opens up new avenues for translational applications in mitigating drug side effects, improving drug efficacy, repurposing of human-targeted drugs as antibacterials or microbiome modulators, and on controlling antibiotic resistance (more detailed discussion 40). However, before any translational application can be pursued, our in vitro findings need to be tested rigorously in vivo (animal models, pharmacokinetics, clinical trials) and understood better mechanistically.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial isolates used in this study were purchased from DSMZ, BEI Resources, ATCC and Dupont Health & Nutrition, or were gifts from the Denamur Lab (INSERM). All strains were recovered in their recommended rich media (resource and literature). The screen and validation experiments were performed in modified Gifu Anaerobic Medium broth (mGAM) (HyServe GmbH & Co.KG, Germany, produced by Nissui Pharmaceuticals) 42, since almost all species could grow robustly in this medium in a manner that is reflective of their gut abundance 8. Due to selecting for robust growth, potential positive effects of drugs in growth could not be detected. Only one strain was grown in Todd-Hewitt Broth (Sigma-Aldrich), one in a 1:1 mixture of mGAM and Gut Microbiota Medium 43 and for one strain, mGAM was supplemented with 60 mM sodium formate and 10 mM taurine; see also Supplementary Table 2). All media were pre-reduced at least 1 day before use under anoxic conditions in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products Inc) (2% H2, 12% CO2, rest N2) and all experiments were performed under anaerobic conditions at 37°C unless specified otherwise.

Species selection

To select a representative core of species in the human gut microbiome, we analyzed 364 fecal metagenomes of asymptomatic individuals from 3 continents 44–47. Species were defined and their abundance quantified as previously described 48,49. A core set of 60 microbiome species was defined (ED Fig. 1b-d), and from this core, 31 species were selected for this screen. 7 additional species were selected for reasons explained in the main text.

Screen of the Prestwick Chemical Library

Preparation of screening plates

The Prestwick Chemical Library was purchased from Prestwick Chemical Inc. (Illkirch, France) with compounds coming dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 10 mM. Compounds were re-arrayed to redistribute the DMSO control wells in each plate and to minimize the total number of 96- and 384- well plates (4 x 384-well plates or 14 x 96-well plates). At the same time, drugs were diluted to a concentration of 2 mM to facilitate further aliquoting, and these plates were stored at -30°C. For each experimental batch (10 replicates in 96-well plates; 20 replicates in 384-well plates) we prepared drug plates in the respective growth medium (2x for 96-well plates, 1x for 384-well plates), and stored at -30°C until use (max 2 months). Before inoculation, plates were thawed and pre-reduced in the anaerobic chamber overnight. The Biomek FXP (Beckman Coulter) liquid handling system was used for all rearranging and aliquoting of the library compounds.

Inoculation

Strains were grown twice overnight to make sure we had a robustly and uniformly growing culture before inoculating the screening plates. For 96-well plates, the second overnight culture was diluted to fresh medium in order to reach a 2x of the aimed starting optical density (OD) at 578nm. Next, 50 μL of this diluted inoculum was added to wells containing already 50 μl of 2x concentrated drug in the respective culture medium using a multichannel pipettor. Final drug concentration was 20 μM and each well contained 1% DMSO. For 384-well plates, we inoculated with a 384 floating pin replicator VP384FP6S (V&P Scientific, Inc.), transferring 1μl of appropriately diluted overnight culture to wells containing 50 μl of growth media, 1% DMSO and 20 μM drug. For bacterial species that reached lower OD in overnight cultures we transferred twice 1 μl of appropriately adjusted OD culture. Both for 96- and 384-well plates, the starting OD was 0.01 or 0.05 depending on the growth preference of the species (Supplementary Table 2).

Screening conditions

After inoculation, plates were sealed with breathable membranes (Breathe-Easy®) to prevent evaporation and cross-contamination between wells, and incubated at 37°C without shaking. Growth curves were acquired by tracking OD at 578nm with a microplate spectrophotometer (EON, Biotek). Measurements were taken every 1-3 hrs after 30-60 seconds of linear shaking, initially manually but later automatically using a microplate stacker (Biostack 4, Biotek), fitted inside a custom-made incubator (EMBL Mechanical Workshop). We collected measurements for 16-24 hrs. Each strain was screened in at least three biological replicates.

Normalization of growth curves and quantification of growth

Growth curves were analyzed by plate. All growth curves within a plate were truncated at the time of transition from exponential to stationary. The end of exponential phase was determined automatically by finding the peak OD (using the median across all compounds and control wells, and accounting for a small increase during stationary phase) and verified by inspection. Using this timepoint allowed us to capture effects of drugs on lag phase, growth rate and stationary phase plateau (ED Fig. 2a). Timepoints with sudden spikes in OD (e.g. caused by condensation) were removed, and growth curves were discarded completely if they had too many missing timepoints (ED Fig. 2a). Similarly, growth curves were discarded if OD fell far outside the normal range (e.g. caused by colored compounds). Three compounds had to be completely excluded from the analysis, as they caused aberrant growth curves: Chicago sky blue 6B, mitoxantrone and verteporfin.

Growth curves were processed by plate to set the median OD at the start and end timepoints to 0 and 1, respectively. Then we determined reference compounds across all replicates as those that did not reduce growth significantly for most drugs: had measurements for > 95% of all replicates, and for which final OD was > 0.5 for more than 142 out of 152 replicates. We used these reference compounds as representatives of uninhibited growth. Since wells containing reference compounds outnumbered control wells within a plate, we used control wells only later to verify the p-value calculation (ED Fig. 2d). After determining reference compounds, we rescaled growth curves such that the median growth of reference compounds at the end point is 1.

While growth curves in control wells and most wells with reference compounds followed the expected logistic growth pattern, a variety of deviations were observed for drugs that influenced growth. To quantify growth without relying on assumptions about the shape of the growth curve, we calculated the area under the curve (AUC) using the trapezoidal rule. While we set the median starting OD to 0, the OD of individual wells deviated from this. We used two different methods to correct for this and determine the baseline for each growth curve (ED Fig. 2a). First, a constant shift was assumed, subtracting the same shift to all timepoints of the growth curve such that the minimum is zero. Second, an initial perturbation was assumed that affects initial timepoints more than later timepoints (e.g. condensation). To correct this, we first subtracted a constant shift as above, and then rescaled the curve such that a timepoint with an uncorrected OD of 1 also has an OD of 1 after correction. AUCs were calculated for both scenarios, rescaled such that the AUC of reference compounds is 1, and then for each compound the baseline correction that yielded an AUC closest to 1 (i.e. normal growth) was selected.

AUCs are highly correlated to final ODs, with a Pearson correlation of 0.95 across all compounds and replicates. Nonetheless, we preferred to use AUCs to decrease the influence of the final timepoint, which will contain more noise than a metric based on all timepoints.

Identification of drugs with anticommensal activity

We detected hits from normalized AUC measurements using a statistical method that controls for multiple hypothesis testing and varying data quality. We fitted heavy-tailed distributions (scaled Student’s t-distribution 50) to the wells containing reference compounds for each replicate and, separately, to each individual plate. These distributions captured the range of AUCs expected for compounds that did not reduce growth, and represented the null hypothesis that a given drug did not cause a growth defect in the given replicate or plate. We calculated one-sided p-values from the cumulative distribution function of the fitted distribution. Within a replicate, each compound was associated with two p-values: one from the plate on which it was measured, and one for the whole replicate. Of those two, the highest p-value was chosen (conservative estimate) to control for plates with little or high noise, and varying levels of noise within the same replicate.

The resulting p-values were well-calibrated (i.e. the distribution of p-values is close to uniform with the exception of a peak at low p-values, ED Fig. 2d) and captured the distribution of controls, which were not used for fitting the distribution and kept for validation. We then combined p-values for a given drug and strain across replicates using Fisher’s method. Lastly, we calculated the False Discovery Rate (FDR) using the Benjamini-Hochberg method 51 over the complete matrix of p-values (1197 compounds by 40 strains). After inspecting representative AUCs for compound–strain pairs at different FDR levels, we chose a conservative FDR cut-off of 0.01.

Drug indications, dose, and administration

We annotated drugs by their primary target organism on the basis of their WHO Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification, or, if there were uncertainties, based on manual annotation. Compounds were classified as: antibacterial drugs (antibiotics, antiseptics), anti-infective drugs (acting against protozoa, fungi, parasites or viruses), human-targeted drugs (i.e. drugs whose mechanism of action affects human cells), veterinary drugs (used exclusively in animals), and finally non-drugs (which can be drug metabolites, drugs used only in research, or endogenous substances). If a human-use drug belonged to several classes, the drug class was picked according to this order of priority (from high to low): antibacterial, anti-infective, and human-targeted drug. This ensured that drugs used also as antibacterials were not classified in the other two categories.

Drugs from the Prestwick Chemical Library were matched against STITCH 4 identifiers 52 using CART 53. Identifiers that could not be mapped were annotated manually. Information about drug indications, dose and administration was extracted from the ATC classification system and Defined Daily Dose (DDD) database. Dose and administration data were also extracted from the Drugs@FDA resource. Doses that were given in grams were converted to mol using the molecular weight stated in the Prestwick library information files. When the dose guidelines mentioned salt forms, we manually substituted the molecular weight. Dose data from Drugs@FDA stated the amount of drug for a single dose (e.g. a single tablet). Analyzing the intersection between Drugs@FDA and DDD, we found that the median ratio between the single and daily doses is two. To combine the two datasets we therefore estimated the single dose as half of the daily dose (Supplementary Table 1).

In general, it is difficult to estimate effective drug concentrations in intestine, since those depend on the dose, the speed of dissolution, uptake and metabolization by human cells and by bacteria, binding to proteins, and excretion mechanisms into the gut. To estimate gut concentrations of drugs based on their dose with a simple model, we relied on an in situ study for posaconazole 19. When 40 mg (57 μmol) of the drug are delivered to the stomach in either an acidic or neutral solution, the maximum concentration in the duodenum reaches 26.3 ± 10.3 and 13.6 ± 5.8 μM, respectively. This is equivalent to dissolving the drug in 300 ml (240 ml of water to swallow the pill as recommended for bioavailability/bioequivalence studies plus ~43 ml resting water in small intestine 54) and an absorption rate of 90%. We collected doses for as many human-targeted drugs as we could find and used the above assumption to estimate small intestine concentrations. To estimate colon concentrations, we relied on reported fecal excretion data (Supplementary Table 1, gathered from DrugBank 5.0 55 and across the literature) assumed a single daily dose, 24 h transit time 56 and a volume of distribution in the colon of 0.6 litres 57 (ED Fig. 3).

IC25 determination/Screen validation

To validate our screen, we selected 25 drugs including human-targeted drugs (19), antiprotozoals (3), one antiparasitic, one antiviral and one 'no-drug' compound. The human-targeted drugs spanned 5 therapeutic classes (ATC codes A, G, L, M, N). Our selection comprised mostly of drugs with extended antibacterial activity in our screen (19 drugs hit > 10 strains). This bias ensured that we can also evaluate false positives. We chose 15 strains to test IC25s (that is the minimal concentration of drug that causes 25% growth inhibition), spanning different phyla (5) and including both sensitive (E. rectale, R. intestinalis) and resistant species (E. coli ED1a).

Compounds for validation were purchased from independent sources (Supplementary Table 1) and dissolved at 100x starting concentration in DMSO. 2-fold serial dilutions were prepared in 96-well U-bottom plates (same as screen). Each row contained a different drug at eleven 2-fold dilutions and a control DMSO well in the middle of the row (in total 8 drugs per plate). These master plates were diluted to 2x assay concentration and 2% DMSO in mGAM medium (50 μl) and stored at -30°C (< 1 month). For the assay, plates were pre-reduced overnight in the anaerobic chamber, and mixed with equal volume (50μl) of appropriately diluted overnight culture (prepared as described for screening section) to reach a starting OD578 of 0.01 and a DMSO concentration of 1% across all wells. OD578 was measured hourly for 24 hrs after 1 min of shaking. Experiments were performed in two biological replicates.

Growth curves were converted to AUCs as described above, using in-plate control wells (no drug) to define normal growth. For each concentration, we calculated the mean across the two replicates. We further enforced monotonicity to conservatively remove noise effects: if the AUC decreased for lower concentrations, it was set to the highest AUC measured at higher concentrations. The IC25 was defined as the lowest concentration for which a mean AUC of below 0.75 was measured. In 68% of cases, IC25s are equal between replicates and in further 22%, there is a two-fold change between replicates, which is within the two-fold error margin reported for inhibitory concentration 58. Additionally, MIC as listed in Supplementary Table 4 was defined as the lowest concentration for which the AUC dropped below 0.1. In the large-scale screen, we detect significant growth reductions, which do not necessarily correspond to complete growth inhibition (ED Fig. 2b). To ensure comparability between the results of the validation procedure and the screen, we used the IC25 metric for benchmarking.

Analysis of side effects

Side effects (SEs) of drugs were extracted from the SIDER 4.1 database 22 using the mapping between Prestwick compounds and STITCH 4 identifiers described above. In SIDER, SEs are encoded using the MedDRA terminology, which contains lower-level terms and preferred terms. Of these, we used the preferred terms, which are more general. We excluded rare SEs that occurred for less than five drugs from the analysis. Drugs with less than seven associated SEs were discarded 59. In a first pass, we identified SEs associated with antibiotics in SIDER, by calculating for each SEs its enrichment for systemic antibiotics (ATC code J01) versus all other drugs using Fisher’s exact test (p-value cut-off: 0.05, correcting for multiple hypothesis testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method). Antibiotics are typically administered in relatively high doses, and some of the enriched SEs might therefore be caused by a dose-dependent effect (e.g. kidney toxicity). We therefore used an ANOVA (Type II) to test if the presence of SEs for a drug is more strongly associated with it being an antibiotic or with its (log-transformed) dose. SEs that were more strongly associated with the dose were excluded from the list of antibiotics-related SEs. Since inhibitory concentration calculations are known to have a two-fold error margin 58, we considered an IC25 of 10-40 μM as being in agreement with the screening result (ED Fig. 5a,c). A higher number of false negatives implies that likely more human-targeted drugs have anticommensal activity.

Data on the incidence rates of SEs in patients was also extracted from SIDER 4.1. As different clinical trials can report different incidence rates, we computed the median incidence rate per drug–SE pair. As SIDER also contains data on the incidence of SE upon placebo treatment, we were able to ensure the absence of systematic biases.

Experimental validation of side effect–based predictions

Selected candidate and control compounds belonged to multiple therapeutic classes (ATC codes A, B, C, G, H, L, M, N, S for candidate compounds and A, C, D, G, H, M N, R, S, V for control compounds). Compounds of interest were purchased from independent sources (Supplementary Table 1) and if possible, dissolved at 5 mM concentration in mGAM. Lower concentrations were used when solubility limit was reached. Solutions were sterile filtered, and three 4-fold serial dilutions were arranged in 96 well plates, aiming at covering a broad range of drug concentrations. Inoculation and growth curve acquisition was performed as described for the IC25 determination experiments.

Chemical genetics in E. coli

Conjugation of the TransBac overexpression plasmid library into E. coli ΔtolC

The TransBac library, a new E. coli overexpression library based on a single-copy vector 60 (H. Dose & H. Mori - unpublished resource) was conjugated in the BW25113 ΔtolC::Kan strain. The receiver strain (BW25113 ΔtolC::kan) was grown to stationary phase in LB medium, diluted to an OD578 of 1, and 200 μl were spread on a LB plate supplemented with 0.3 mM diaminopimelic acid (DAP). Plates were dried for 1 hour at 37°C and then a 1536 colony array of the library carried within a donor strain (BW38029 Hfr (CIP8 oriT::cat) dap-61) was pinned on top of the lawn. Conjugation was carried out at 37°C for ~6 hours, and the first selection was done by pinning on LB plates supplemented with tetracycline only (10 μg/ml) and growing overnight. Two more rounds of selection followed on LB plates containing tetracycline (10 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml) to ensure killing of parental strains and select only for tolC mutants carrying the different plasmids.

Chemical genetic screen

The screen was carried out under aerobic conditions on solid LB Lennox medium (Difco), supplemented with 30 μg/ml kanamycin, 10 μg/ml tetracycline, the appropriate drug, and 0 or 100 μM IPTG. Drugs were used at the following sub-inhibitory concentrations for the tolC mutant: diacerein 20 μM, ethopropazine hydrochloride 160 μM, tamoxifen citrate 20 μM, niclosamide 1.25 μM, thioridazine hydrochloride 40 μM, methotrexate 320 μM, or for the wildtype: metformin 100 mM. The 1536 colony array of BW25113 ΔtolC::kan mutant carrying the TransBac collection was pinned on the drug-containing plates, and plates were incubated for 16-38 hours at 37°C. In the case of metformin we used the version of the TransBac library, in which each plasmid complements its corresponding barcoded single-gene deletion mutant 60, since we did not need to use the ΔtolC background for sensitizing the cell. Growth of this library was determined at 0 and 100 mM metformin (both in the presence of 0, 50 and 100 μM IPTG). All plates were imaged using an 18 megapixel Canon Rebel T3i and images were processed using the Iris software 41.

Data analysis

We used colony size to measure the fitness of the mutants on the plate. For standardisation of colony sizes, we subtracted the median colony size and then divided by a robust estimate of the standard deviation (removing outliers below the 1st and above the 99th percentile). We found edge effects affecting up to five rows and columns around the perimeter of the plate. We therefore first standardised colony sizes across the whole plate using only colony sizes from the inner part of the plate as reference. To remove the edge effects, we subtracted from each column its median colony size, and then from each row its median colony size. Finally, we standardised the adjusted colony sizes using the whole plate as reference. The distribution of adjusted colony sizes was right-skewed (i.e. more outlier colonies with larger size), suggesting a log-normal distribution. At the same time, the presence of outliers suggested that a logarithmic equivalent of the Student’s t-distribution with variable degree of freedom 50 would be more suitable. We fitted such a distribution for each plate and calculated p-values for both tails of the distribution. This approach assumes that the overexpression of most genes does not affect growth in response to drug treatment. p-values were combined using Fisher’s method across replicates and IPTG concentrations (since we noticed that different IPTG concentrations resulted in largely the same results – i.e. plasmids are leaky). We corrected for multiple hypothesis testing for each drug individually using the Benjamini-Hochberg method 51.

Analysis of common resistance mechanisms

To determine a relationship between the number of human-targeted drugs (h) and the number of antibacterial drugs (a) that affect each strain, we determined the odds ratio (OR):

Where H=203 and A=122 are the numbers of human-targeted and antibacterial drugs that show activity against any strain, respectively. We computed the nonlinear least-squares estimate for OR based on the following equation:

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Screen set-up and species selection.

a. Drugs from the Prestwick Chemical Library (arranged in either 96- or 384-well format) were diluted in growth media (for most part mGAM) and pre-reduced in a Coy anaerobic chamber before inoculation with one out of 40 different human gut microbes. Bacterial growth was monitored for 16-24 hour at 37°C. Growth curves were acquired at least in triplicates for each drug-microbe interaction (see also Methods). b. Species with a minimum relative abundance of 1% in at least one sample and a prevalence of 50% across samples (the latter estimated by rarefying to 10,000 reads mapping to taxonomic markers) were included in the set of core species. Boxplots show relative abundances of core species grouped by genus (according to NCBI taxonomy) and colored by phylum (see key). The inner box indicates the inter-quartile range (IQR), with the median as black vertical line; the outer bars extend to the 5th and 95th percentiles; circles, outliers. To the right of the boxplots, prevalence is depicted by bars, and next to this the species diversity is shown: grey boxes indicate species represented in the screen with box widths corresponding to mean relative abundance within the genus. c. Relative abundance of genera of which at least one species was represented in the screen cumulates to 78% of the assignable fraction of reads (median across all samples, upper panel); first four boxplots show abundance within each study identified by country codes underneath 44–47. When directly cumulating the relative abundance of represented species the corresponding median is 60% (lower panel). Boxes span the IQR and whiskers extend to the most extreme data points up to a max of 1.5 times the IQR. d. Core species are shown in the order of their median abundances across all samples. Relative abundance boxplots and prevalence bars are defined as in (b) and grey boxes underneath indicate species screened in this study. Numbers in brackets correspond to specI cluster identifiers (version 1) 48.

Extended Data Figure 2. Data analysis pipeline for identifying compounds with anticommensal activity.

a. Schematic overview of the data analysis pipeline. All steps (determination of time cutoff and removal of noisy points; normalization and selection of reference compounds, baseline correction, AUC calculation and hit calling) are explained in detail in methods. On first panel dashed lines on plot on the right depict the three possible effects that a drug can have on the growth of a microbe: increase the lag phase, decrease the growth rate or the stationary phase plateau. All effects are captured by cutting off the growth curves upon transition to stationary phase for most compounds (most drugs do not affect growth). On second panel, median growth rates for two drugs on same plate are depicted and normalized, whereas baseline correction (third panel) is applied at the individual wells. b. Growth curves (normalized OD) of Bacteroides ovatus in three exemplary drug cases for the three biological replicates (upper panel) - meclofenamic acid (red), moricizine (green) and diacerein (blue). Light and dark grey shades represent the 50% and 90% confidence intervals for normal growth. Normalized AUC histograms for all drugs in the three biological replicates for the case of B. ovatus. Meclofenamic acid is just below the hit threshold, moricizine is a hit with partial but strong growth inhibition, and diacerein almost completely inhibits the growth of B. ovatus. c. For most species, correlation between replicates is very high (median: 0.88). d. For both controls and reference compounds, p-values were approximately uniformly distributed. Determining the background distribution of uninhibited growth using reference compounds is validated by their very similar behavior with control wells. Other drugs (i.e. drugs not used as reference compounds) show a clear enrichment of low p-values.

Extended Data Figure 3. Anticommensal activity relative to compound- and compartment-specific drug concentrations.

Simplified pharmacokinetic estimation of small intestine and colon concentrations by assuming that one dose of an orally administered drug (extracted from Drugs@FDA and Daily Defined Dose (DDD) of the ATC) reaches the intestine and is dissolved/absorbed similarly as the well-absorbed drug, posaconazole 19 (see also Supplementary Table 1). After absorption into the liver via the portal circulation, the drug enters circulation through the hepatic veins and reaches its characteristic plasma concentration. The two main routes of drug elimination are either secretion via kidney/urine or secretion into the intestine via the biliary duct. In the intestine, drugs can be reabsorbed in a circuit called the enterohepatic cycle or excreted in stools. Compounds that are either poorly absorbed in the small intestine or secreted by bile reach the large intestine. Considering the measured excreted fraction of the drug in feces (both changed and unchanged compound, as we do not know whether drug is metabolized in liver or gut), and assuming a large intestinal transit time of 24 h 56 and a volume of distribution in the colon of 0.6 liters 57, we estimated the colon concentrations of the human-targeted drugs in our screen (see also Supplementary Table 1). Histograms for drug dose, plasma concentrations, estimated small intestine concentration, urinary and fecal excretion and estimated colon concentrations depict the respective distributions for human-targeted drugs color-coded based on their anticommensal behavior in our screen. Dashed lines indicate medians, vertical lines highlight the drug concentration used in our screen (20 μM). Interactions between drugs and microbiota are possible throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract with microbial load having a gradient-like distribution (ileum and colon containing the largest numbers), which can be though disturbed during disease 18. Also drugs can be modified at several stages: by host digestive and intestinal epithelial enzymes, by phase I and phase II metabolism in the liver and by microbial enzymes. Some of these processes neutralize each other, resulting in reconversion into the original compound.

Extended Data Figure 4. Effects of metformin in gut microbiota in vivo correlate with its in vitro activity.

a. IC25’s of the antidiabetic drug metformin for a selection of 22 strains. Metformin did not inhibit any species in our screen as the concentration used, 20 μM (red line), is below the IC25 of all strains. However, at its estimated small intestinal and colon concentration of 1.5 mM (blue line), metformin would inhibit 3/22 tested strains. This exemplifies that more human-targeted drugs would interfere with bacterial growth if doses were to be increased towards drug- and body-site-specific concentrations. b. IC25’s of metformin correlate well with its observed effects in humans 62, based on the four species that overlap between the two studies. Significant treatment effects on the species level were mapped to our set of strains for which we had determined IC25’s.

Extended Data Figure 5. Validation of the screen and conservative hit-calling.

a-b. Validation of our screen by IC25 determination for 25 selected drugs in a subset of up to 27 strains reveals high precision (94%) and recall (85%). We considered IC25 as the lowest concentration that reduces growth by >25% (Methods). Breakdown into active and inactive compounds for drugs concentrations at the 20 μM concentration, used in our screen. True positives (TP) – green; false positive (FP) – red; true negatives (TN) – grey; false negative (FN) - blue. c. Number of drugs with anticommensal activity versus the applied FDR threshold for all compounds (left) and human-targeted drugs (right). Increasing the FDR threshold from 0.01 to 0.1 (vertical grey lines) would nearly double the fraction of drugs impacting human gut microbes. d. IC25’s of 25 drugs in up to 27 individual strains (see also panels a-b.). The white area indicates the drug concentration ranges tested for each drug. Symbol sizes depict number of strains with a particular IC25, symbol colors indicate categorization into FN, FP, TN or TP, and symbol shapes qualify whether actual IC25s were determined or IC25 was deemed to be higher or lower from the highest and lowest concentration tested, respectively. Vertical line indicates the drug concentration used in screen (20 μM). IC25’s for all drug-strain pairs are listed in Supplementary Table 4. Particular drugs were responsible for FNs in our screen (acarbose, loperamide, thioridazine), presumably due to drug decay.

Extended Data Figure 6. IC25 relation to drug concentrations in human body.

For drug-strain pairs with measured IC25’s (Supplementary Fig. 5), we compared IC25’s with plasma and estimated small intestine and colon concentrations by plotting the number of strains that are affected in relation to whether they are above/below relevant body concentrations (color code). With the exception of estradiol valerate and 5-FU (only plasma concentrations available), all other drugs with available body concentrations reach concentrations high enough in the body to reach IC25’s for at least one gut microbial species (out of up to 27 tested for IC25’s).

Extended Data Figure 7. Concordance of drug in vitro species susceptibilities and drug-mediated shifts in microbiome composition of patients.

a. Association coefficients between PPI usage and relative taxonomical abundance in fecal microbiomes of PPI users from two studies (twins, UK cohort – green 4; and 3 independent cohorts from the Netherlands 3- blue) (left) are compared to in vitro growth inhibition of isolates with same taxonomic rank in the presence of PPIs (omeprazole, lansoprazole and rabeprazole) as accessed by FDR adjusted p-values (q-values) in our screen (right). Point size in the left panel corresponds to the q-value as reported in the original study. Reduced taxa in patients (negative association coefficient, left to vertical black line) were mostly inhibited by PPIs in our screen (q-value below 0.01, left to vertical black line), while enriched taxa were insensitive to PPIs. Box plots show: centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. For fewer than 10 data points, all points are shown individually. b. Spearman correlation coefficients between association coefficients of fecal microbiome composition after consumption of amoxicillin or azathioprine 7 and the screen p-values. The histogram represents the background distribution of correlations between the in vitro data for all human-targeted drugs and the in vivo response to these drugs; correlations with amoxicillin/azathioprine are highlighted by triangles c. Comparisons between association coefficients and drugs from different therapeutic classes as assessed by Falony et al. 7 and our in vitro data. d. A bipolar disease cohort study 6 reported a significantly decrease in abundance of Akkermansia upon atypical antipsychotics (AAP) treatment. Comparing distributions of adjusted p-values from our screen for different strains, Akkermansia muciniphila was significantly more sensitive than all other strains to antipsychotics in general and APP in particular (p = 0.02 and p = 0.09, one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test). In contrast, A. muciniphila is relatively more resistant than other strains across all human-targeted drugs (p = 0.0005, one-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test). Violin plot shows estimated density of points with the estimated median as vertical bar. For fewer than 10 data points, all points are also shown individually.

Extended Data Figure 8. Evaluation of anticommensal activity predictions based on side-effects.

a. IC25’s of 26 candidate compounds (p-value for enrichment of antibiotic-related side effects < 1e-4, using a one-sided Fisher’s exact test) and 16 control compounds (see also Fig. 3d & panel d of this Figure) were determined for 18 representative strains and results are depicted as an IC25 heatmap. Drugs are ordered according to their side effect similarity to antibiotics from left to right (for antibiotic-related side effects see Supplementary Table 5). Qualifiers indicate whether IC25s are higher/lower than the indicated concentration; if no symbol the box depicts the exact IC25. If highest tested concentrations did not reduce growth of any of the tested strains, the compound was classified as inactive (e.g. Topiramate). b. Dose of the tested compounds according to the Defined Daily Dose and Drugs@FDA databases (see also Supplementary Table 1). c. Based on a compound’s recommended dose and its median IC25 for different bacterial strains, we estimated the number of doses need to reach this IC25. This number was plotted against the drug’s p-value for enrichment of antibiotics-related side effect. For direct comparison between the two groups, see Fig. 3e. Circles in magenta depict drug–strain pairs for which growth was reduced, showing a clear correlation between p-values and the estimated number of doses (magenta line). To rule out that the tested concentration range is causing this correlation, we also depict the estimated number of doses corresponding to the highest tested concentration (grey line), which exhibits no clear dependency between p-value and number of doses. A vertical line across all panels connects all parameters attributable to a particular drug. d. Recommended single drug doses of human-targeted drugs with no anticommensal activity in our screen plotted against enrichment in antibiotic-related side effects (n=339). Candidate and control drugs selection for testing for anticommensal activity at higher concentrations were selected based on similarity to antibiotic-related side effects (vertical black line depicts prediction threshold) and aiming at drugs used at higher doses than concentration in our screen (horizontal dashed line). Purple and dark grey triangles indicate hits and non-hits from this validation effort, respectively. e. Ratios between IC25 and estimated colon concentrations are significantly lower (p = 0.017, two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test) for candidate drugs than for control drugs. For candidate drugs, 16/52 (31%) IC25’s were below the estimated colon concentrations while for control drugs this fraction was only 5/50 (10%). Box plots show: centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers.

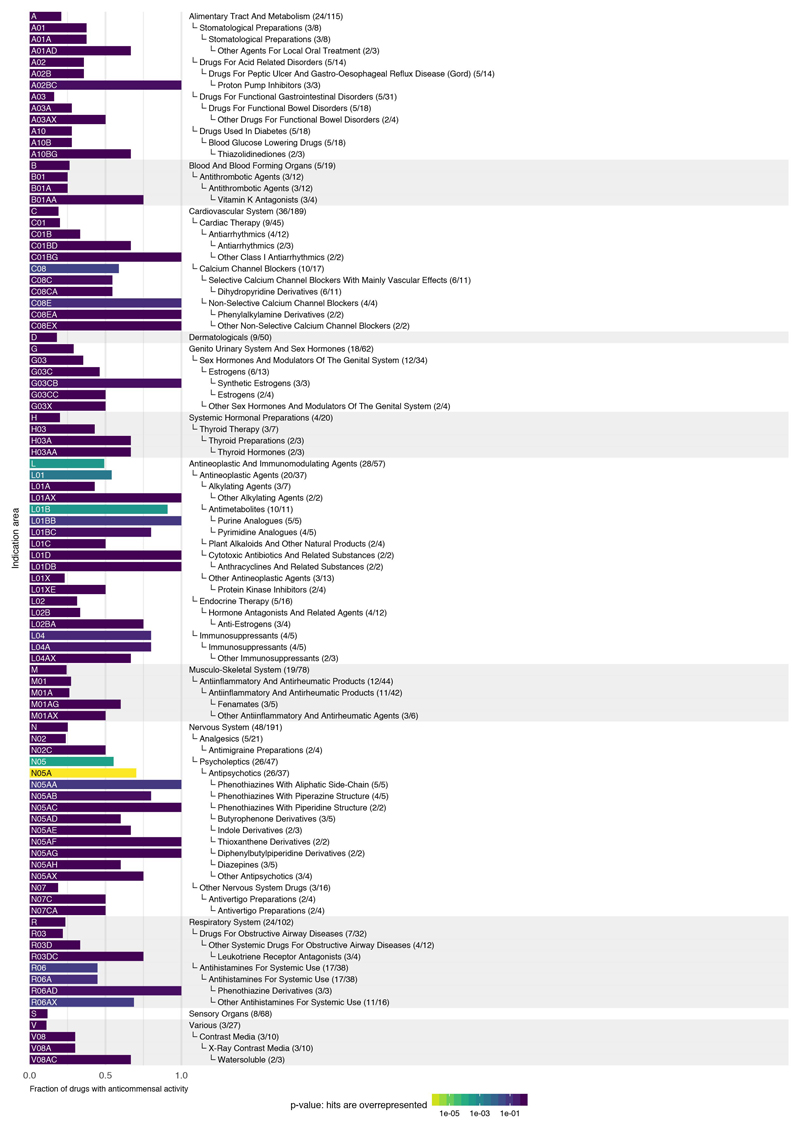

Extended Data Figure 9. Drug therapeutic classes with anticommensal activity.

a. Fraction of drugs with anticommensal activity by ATC indication area (bars). All first-level indication areas and significantly enriched lower levels are shown (see also ED Fig. 10). Significance (p-value, one-sided Fischer’s exact test) is controlled for multiple hypothesis testing (Benjamini-Hochberg) independently at each ATC hierarchy level. b. Heat map of anticommensal activity and chemical similarities of human-targeted drugs within the three significantly ATC indication levels from a. Colors represent the median of drug pairwise Spearman correlations within and between subgroups depicted, calculated from the growth profiles of the 40 strains in each drug (p-values) or their Tanimoto scores 63. Examples of structurally similar (phenothiazines; N05AA-AC) and diverse (N05AF-AX) antipsychotics that all elicit similar responses in our screen are marked. c. Antipsychotics exhibit higher similarity in gut microbes they target than that expected based on their structural similarity (p-value = 2e-19 estimated from random permutations; other classes depicted show no significance difference). Box plots show: centre line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5x interquartile range; points, outliers. Notches correspond roughly to a 95% confidence interval for comparing medians.

Extended Data Figure 10. Drugs with anticommensal activity for all hierarchy levels of the ATC classification system.

Fraction of drugs with anticommensal activity for all indication areas of the ATC classification scheme with a high fraction of active compounds. Shown are indication areas that contain at least two active compounds and a fraction of at least 50% active compounds, their parent terms and all top-level indication areas. Significance (p-value, one-sided Fischer’s exact test) is indicated by the bar color and corrected for multiple hypothesis testing (Benjamini-Hochberg) independently at each hierarchy level of the ATC. Many smaller classes, including PPIs (A02BC), non-selective calcium channel blockers (C08E), synthetic estrogens (G03CB), leukotriene receptor antagonists (R03DC) and phenothiazine and other antihistamines (R06AD & R06AX) are enriched, but due to multiple testing and small numbers of drugs tested in each group, they do not reach a significant p-value.

Extended Data Figure 11. Comparing chemical similarity of drugs and similarity of hit profiles across gut microbes.

a. Heat map of anticommensal activity and chemical similarities for all active human-targeted drugs in our screen. Drugs are clustered according to chemical similarity. Colors represent the median of drug pairwise Spearman correlations within and between subgroups depicted, calculated from the growth profiles of the 40 strains in each drug (p-values) or their Tanimoto scores 63. Several prominent groups are color coded. Only drugs of some classes share both chemical similarity and have similar effects on the 40 strains – for example: phenothiazine antipsychotics & antihistamines (N05A & R06AD), structurally similar dibenzothiazepines & dibenzoxazepines for antipsychotics and antidepressants (N05AH & N06AA), PPIs (A02BC), antiestrogens (L02BA), synthetic estrogens (G03CB) and anti-inflammatory fenamates (M01AG & M02AA06). b. A mild correlation exists between chemical similarity (Tanimoto scores) and anticommensal activity similarity (drug pairwise Spearman correlations) - rs = 0.12 (p-value of Spearman’s test < 2e-16).

Extended Data Figure 12. More complex, bulkier and heavier human-targeted drugs are more effective against Gram-positive bacteria.

Fraction of inhibited Gram-positive (blue, N = 22) or -negative (red, N = 18) strains per drug plotted against different chemical properties of the drugs. Chemical properties, such as complexity (based on atom types, symmetry, computed using the Bertz/Hendrickson/Ihlenfeldt formula), molecular weight, TPSA (topological polar surface area, an estimate of the area - in Å squared), volume (in cubic Å) and XLogP (distribution coefficient that is a measure of differential solubility in octanol/water) were obtained from PubChem 64. For each chemical property, we used a Type II ANOVA to test for linear dependency between the fraction of affected species and the chemical property (slope). Additionally, we tested if this dependency depended on the Gram stain (slope difference). It is possible that there is no significant slope without considering Gram stain, but that there is a significant difference between the slopes for the two Gram stains. Lines show a linear fit to the data, with 95% confidence intervals as shaded area.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Pedro Beltrao (EBI), KC Huang (Stanford) and Filipe Cabreiro (UCL) for feedback on the manuscript, Friedrich Rippmann (Merck KGaA) for pointing to the delayed onset of antipsychotics, Sebastian Wicha (University of Hamburg) for discussions on drug concentrations, John Overington (Medicines Discovery Catapult) for help with drug plasma concentrations, and all four labs’ members for fruitful discussions - in particular T. Hodges for suggestions on the manuscript and M. Driessen for experimental support. We thank the EMBL mechanical workshop for the custom-made incubator. We acknowledge funding from EMBL and the Microbios grant (ERC-AdG-669830). LM and MP were supported by the EMBL Interdisciplinary Postdoc (EIPOD) programme under Marie Sklodowska Curie Actions COFUND (grant 291772). ATe and ARB were supported by the Sofja Kovaleskaja Award of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation to ATy.

Footnotes

Data Availability

Data is available from FigShare: http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4813882

Code Availability

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Scripts for analysing data and generating figures are available at https://git.embl.de/mkuhn/drug_impact_gut_bacteria. A snapshot of the repository has been deposited together with the data.

Author Contributions

The study was conceived by KRP, PB and ATy; designed by LM, MP, GZ, ARB and ATy; supervised by KRP, PB and ATy. In vitro screening was established by MP and performed by LM, MP, ATe and KCF. Follow-up and validation experiments were conducted by LM, MP and EEA. HD and HM constructed and provided the Transbac library. Data preprocessing was performed by MK and GZ; statistical analyses by MK; data curation by LM, MK and EEA; data interpretation by LM, MP, MK, GZ, KRP, PB and ATy. LM, MK, GZ, KRP, PB and ATy wrote the manuscript with inputs from MP and ARB; LM, MK and GZ designed figures with inputs from KRP, PB and ATy. All authors approved the final version for publication.

Author Information

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kåhrström CT, Pariente N, Weiss U. Intestinal microbiota in health and disease. Nature. 2016;535:47. doi: 10.1038/535047a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forslund K, et al. Disentangling type 2 diabetes and metformin treatment signatures in the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2015;528:262–266. doi: 10.1038/nature15766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imhann F, et al. Proton pump inhibitors affect the gut microbiome. Gut. 2016;65:740–748. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson MA, et al. Proton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut. 2016;65:749–756. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers MA, Aronoff DM. The influence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the gut microbiome. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:178 e171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flowers SA, Evans SJ, Ward KM, McInnis MG, Ellingrod VL. Interaction between Atypical Antipsychotics and the Gut Microbiome in a Bipolar Disease Cohort. Pharmacotherapy. 2016 doi: 10.1002/phar.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falony G, et al. Population-level analysis of gut microbiome variation. Science. 2016;352:560–564. doi: 10.1126/science.aad3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tramontano M, et al. Nutritional preferences of the human gut bacteria reveal their metabolic idiosyncasies. Nat Microbiol. 2017 doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0123-9. accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ejim L, et al. Combinations of antibiotics and nonantibiotic drugs enhance antimicrobial efficacy. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:348–350. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taber HW, Mueller JP, Miller PF, Arrow AS. Bacterial uptake of aminoglycoside antibiotics. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:439–457. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.439-457.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blaser MJ. Antibiotic use and its consequences for the normal microbiome. Science. 2016;352:544–545. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rani N, Sharma A, Singh R. Imidazoles as promising scaffolds for antibacterial activity: a review. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2013;13:1812–1835. doi: 10.2174/13895575113136660091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harbut MB, et al. Auranofin exerts broad-spectrum bactericidal activities by targeting thiol-redox homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:4453–4458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1504022112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farha MA, et al. Antagonism screen for inhibitors of bacterial cell wall biogenesis uncovers an inhibitor of undecaprenyl diphosphate synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:11048–11053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511751112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pasolli E, Truong DT, Malik F, Waldron L, Segata N. Machine Learning Meta-analysis of Large Metagenomic Datasets: Tools and Biological Insights. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1004977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell. 2016;165:1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arumugam M, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. nature09944 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donaldson GP, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:20–32. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hens B, Brouwers J, Corsetti M, Augustijns P. Supersaturation and Precipitation of Posaconazole Upon Entry in the Upper Small Intestine in Humans. J Pharm Sci. 2016;105:2677–2684. doi: 10.1002/jps.24690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bailey CJ, Wilcock C, Scarpello JH. Metformin and the intestine. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1552–1553. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schloissnig S, et al. Genomic variation landscape of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2013;493:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature11711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhn M, Letunic I, Jensen LJ, Bork P. The SIDER database of drugs and side effects. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:D1075–1079. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodet CA, 3rd, Jorgensen JH, Drutz DJ. Antibacterial activities of antineoplastic agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:437–439. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.3.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stringer AM, Gibson RJ, Bowen JM, Keefe DM. Chemotherapy-induced modifications to gastrointestinal microflora: evidence and implications of change. Curr Drug Metab. 2009;10:79–83. doi: 10.2174/138920009787048419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]