Abstract

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of individual CBT (ICBT) and group CBT (GCBT) for referred children with anxiety disorders within community mental health clinics.

Method

Children (N=165) referred to five clinics in Norway, aged 7–13 years, with primary DSM-IV separation anxiety disorder (SAD), social anxiety disorder (SOC), or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) participated in a randomized clinical trial. Participants were randomized to ICBT, GCBT, or wait list (WL). WL participants were randomized to one of the two active treatment conditions following the wait period. Primary outcome was loss of principal anxiety disorder over 12 weeks and 2-year follow-up.

Results

Both ICBT and GCBT were superior to WL on all outcomes. In the ITT analysis, 52% in ICBT, 65% in GCBT, and 14% in WL were treatment responders. Planned pairwise comparisons found no significant differences between ICBT and GCBT. GCBT was superior to ICBT for children diagnosed with SOC. Improvement continued during two-year follow-up with no significant between group differences.

Conclusions

Among anxiety disordered children, both individual and group CBT can be effectively delivered in community clinics. Response rates were similar to those reported in efficacy trials. Although GCBT was more effective than ICBT for children with SOC following treatment, both treatments were comparable at 2-year follow-up. Drop-out rates were lower in GCBT than ICBT, suggesting that GCBT may be better tolerated. Response rates continued to improve over the follow-up period with low rates of relapse.

Public Health Significance

Findings indicate that both ICBT and GCBT can be effectively delivered by community mental health practitioners with only a minimal amount of formal training. Outcomes were similar to those reported in more controlled settings.

Keywords: pediatric anxiety disorders, treatment effectiveness, cognitive behavioral therapy, implementation study

As a group, anxiety disorders in youth are the most common mental health disorders and typically have their onset in childhood or early adolescence (Kessler et al., 2005). Untreated anxiety disorders in youth are associated with poor functioning in several areas of life as well as conferring a significant risk for psychopathology and functional impairment later in life (Copeland, Angold, Shanahan, & Costello, 2014; Swan & Kendall, 2016). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an empirically supported treatment (EST) for pediatric anxiety disorders (Hollon & Beck, 2013; James, James, Cowdrey, Soler, & Choke, 2013; Reynolds, Wilson, Austin, & Hooper, 2012) and is considered a first-line treatment (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007). However, despite robust evidence from efficacy studies (e.g., Kendall, Hudson, Gosch, Flannery-Schroeder, & Suveg, 2008; Walkup et al., 2008), CBT remains underutilized in community care settings where most youth receive treatment for mental health problems (Schoenwald & Hoagwood, 2001).

There are a number of reasons why the uptake of ESTs in community mental health clinics is low. One reason is practitioner skepticism fueled by (1) their beliefs that efficacy studies use highly selective and homogeneous participants that bear little resemblance to the clients they see in everyday practice and (2) the finding that effectiveness studies report smaller effect size estimates than efficacy trials (e.g., Bodden et al., 2008; Wergeland et al., 2014). Therefore, it is important for community clinicians to be involved in developing and evaluating treatment (Weisz, Sandler, Durlak, & Anton, 2005), and it remains essential to conduct effectiveness evaluations as part of the process of evaluating and developing treatment.

Most of the current evidence-base for the benefits of CBT for anxiety comes from efficacy studies. Efficacy studies test interventions under ideal circumstances with rigorous control over study factors (Haynes, 1999). Study therapists are usually highly trained and have small caseloads, participants are more homogeneous than those seen in usual care settings (Weisz, Weiss, & Donenberg, 1992), and staff and facilities dedicated to research are much less in the settings in which most children receive treatment (Southam-Gerow, Weisz, & Kendall, 2003). Effectiveness studies, on the other hand, test interventions in real-world settings--the usual circumstances of clinical practice (Haynes, 1999). The distinction between efficacy and effectiveness trials can be considered to lie on a continuum with varying degrees of control over study variables.

Efficacy studies find that between 55–60% of treated children with anxiety disorders improve significantly after receiving CBT (James et al., 2013). Some effectiveness trials find response rates similar to those observed in efficacy trials (e.g., Barrington, Prior, Richardson, & Allen, 2005; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010) whereas others have observed lower response rates when evaluating ESTs in community settings (e.g., Bodden et al., 2008; Wergeland et al., 2014). Several effectiveness studies are limited by small sample sizes (Barrington et al., 2005; Lau, Chan, Li, & Au, 2010; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010).

The majority of trials to date have examined treatments that target the most common and impairing anxiety disorders: separation anxiety disorder (SAD), social anxiety disorder (SOC), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Although studies consistently document a significant main effect for CBT, secondary analyses suggest that children with SOC respond less favorably than do children with SAD or GAD (Compton et al., 2014; Hudson et al., 2015; Kerns, Read, Klugman, & Kendall, 2013). This finding suggests that current treatment protocols may need to be modified to better address the needs of children and adolescents with SOC by providing more clinically relevant exposure exercises. This may be difficult to do within an individual (youth-focused) CBT treatment format in most community clinics where therapists have tight schedules preventing them from seeking out the very situations that trigger the youth’s anxiety within the time of a treatment session.

Research has found that CBT can be modified and delivered in a variety of formats, including groups. When averaged across anxiety disorders, the majority of studies have not found significant differences between individual and group formats (Flannery-Schroeder & Kendall, 2000; Liber et al., 2008; Manassis et al., 2002; Wergeland et al., 2014). However, systematic reviews report large effect size estimates for individual CBT and moderate effect size estimates for group CBT (Reynolds et al., 2012). From a practical perspective, the two formats have advantages and disadvantages. On one hand, individual CBT allows for more personalized attention and greater flexibility on the part of the therapist to tailor treatment components to a particular child. However, planning exposure tasks that meet the needs of children with SOC may be more challenging within the context of individual therapy (Compton et al., 2014). On the other hand, therapists conducting group CBT may be less able to tailor treatment components to every child, but the group format may allow for more ecologically valid exposure exercises for youth with SOC. The fact that children in group treatment must interact with peers (Manassis et al., 2002), means that the format itself provides “ready-made” exposure opportunities. In addition, group treatment is a cost-effective way of providing empirically supported care to more children using fewer clinician resources compared to individual CBT (Flannery-Schroeder, Choudhury, & Kendall, 2005).

Prior to the present study, we conducted a pilot project at two local community mental health clinics. The pilot project evaluated the feasibility of doing group CBT for referred children with anxiety disorders (Martinsen, Aalberg, Gere, & Neumer, 2009). Group treatment was not part of the standard treatments offered in these community clinics, but clinicians expressed an interest in learning this format of delivery. In most group-based CBT protocols, youth meet directly with the group after their baseline assessment. Based on feedback received following the pilot project, some therapists reported that tailoring exposure exercises that met the needs of all children in the group was a challenge. Therapists also felt that initially they did not know each individual child well enough to adequately plan and prepare for each group session. At the same time the therapists noticed that some of the children were very slow to participate in group and were hesitant to engage with peers. Based on the pilot experience, we modified the group CBT protocol to meet the needs of the therapists and participants. The group CBT evaluated in this study had youth and therapists meet individually for the first three sessions before transitioning to group. This adjustment allowed each therapist and child to get to know one another, to build trust, to address concerns the child might have about group therapy, and to facilitate planning exposure tasks. This adjustment also gave the child the opportunity to become familiar with the treatment model and address concerns privately before working within a group.

The present study examined the effectiveness of individual CBT and the modified group CBT for referred children with anxiety disorders within outpatient community mental health clinics. We hypothesized that individual CBT and group CBT would outperform a waitlist control condition. Although we did not expect significant differences between the two treatment formats overall, we hypothesized that children with SOC would respond more favorably to the adapted group CBT protocol than to individual CBT.

Method

Design and Implementation

The present study evaluated the relative effectiveness of two formats of CBT treatment delivery (i.e., individual vs. group) compared to a 12-week waitlist. Following the waitlist period, waitlist participants were re-randomized to one of the two treatment formats. This design allowed for two sets of analyses. The first set compared the 12-week outcomes across the three conditions: individual CBT (ICBT), group CBT (GCBT), and waitlist (WL). The second set, which included the WL participants who then received an active treatment, compared 12-week and 2-year outcomes for the two treatment conditions (i.e., ICBT; GCBT)1. The study protocol was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics.

Participants

Participants were 165 youth (54.5% male, age M=10.46, SD=1.49, age range 7–13 years) referred for mental health services to one of five child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS) clinics in South-Eastern Norway. Inclusion criteria were: (1) children between the ages of 7 and 13 years, (2) a primary diagnosis of SAD, GAD, or SOC (according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision [DSM-IV-TR], American Psychiatric Association, 2000), (3) significant functional impairment, (4) an IQ of 70 or higher, and (5) at least one parent had to be proficient in Norwegian. Exclusion criteria were: (1) a mental health disorder with a higher treatment priority, (2) pervasive developmental disorder(s), (3) psychosis, or (4) current use of anxiolytic medication.

Sampling Procedures and Determination of Eligibility

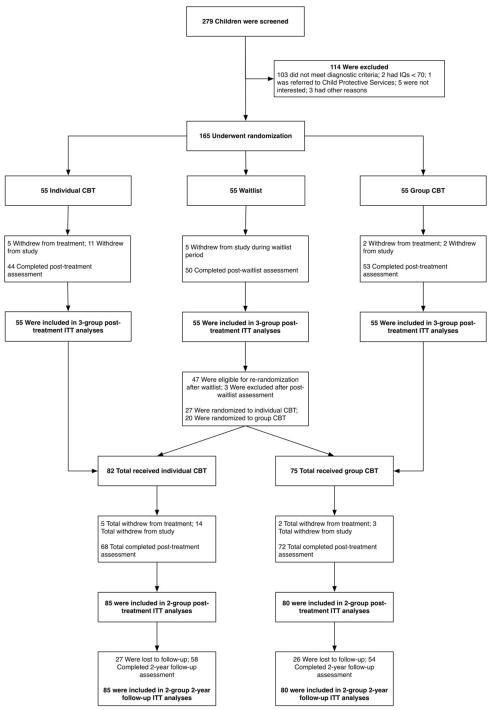

Recruitment occurred from September 2008 through October 2011. Participants were recruited among referred children at one of five CAMHS clinics in South-Eastern Norway. In Norway, all children who receive mental health services at a CAMHS must be referred by an allied professional, most commonly a general practitioner or school psychologist. During the study enrollment period, the parent(s) of any new patient was approached for possible participation if his or her child was within the appropriate age range and met at least one of the two following criteria: (1) anxiety listed as the reason for referral to the CAMHS clinic or (2) a t-score 65 on the internalizing problems subscale on the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), which was routinely sent out to all new referrals. Of the included participants, 92 were referred for anxiety problems; 73 were referred for other reasons but were eligible based on their elevated CBCL scores. After obtaining informed consent, the child and parent(s) underwent an assessment of the child’s anxiety symptomology and comorbidity. Progression through the assessment process was typically completed within three weeks and is summarized in the Consort Diagram (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study enrollment.

Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions using a computergenerated permuted blocking procedure, stratified by clinic. Children were randomized in blocks of five. Waitlist participants were re-randomized to one of the two treatment conditions using the same computer-generated procedure and stratification variables.

Treatments

All treatment provided in ICBT and GCBT followed a Norwegian translation of the Coping Cat manual (Kendall & Martinsen, 2008; Kendall, Martinsen, & Neumer, 2006). Treatment in both conditions consisted of 14 sessions (12 child sessions and two parent sessions) delivered over a 12-week period. Each child received training in anxietymanagement skills and received behavioral exposure to anxiety-provoking situations. Exposure tasks were tailored to the individual child. For a child with SAD, for example, insession exposure would be having the parent outside the therapy room and the child not able to check-up on the parent during the session, or asking the parent to drop the child off and then leave to run an errand. At home, the exposure would be having the child do something with a friend without having the parent present. For children with SOC, the group format allowed for a range of in-session exposures, such as introducing yourself to a new person and speaking in front of the group. As homework, the child would practice in other settings, such as reading aloud in school. For a child with GAD, an in-session exposure task could be writing a story involving his/her worries coming true but without seeking reassurance from the therapist or others. At home, the child could watch the news and practice not seeking reassurance from the parent afterwards. Children randomized to GCBT met individually with one of the two group therapists for the first three sessions before joining a group from session four onwards. The GCBT approach comprised treatment groups consisting of a mean of 4.63 participants each (range 3–5).

Setting and therapists

Five community clinics participated, covering both urban and rural areas. In Norway, mental health services are provided free of charge and there is marginal use of private mental health practitioners for children. Each clinic enrolled, on average, 33 participants with a range of 17–45 participants.

Treatment was provided by 32 community therapists (M age=34.7, SD=5.9, range 2749, 81.3% female) treating an average of five children each (range 1–19). The therapists had an average of 44.3 months of clinical experience with youth (SD=35.6, range 3–156), mainly from CAMHS. Twenty therapists were licensed clinical psychologists (minimum master level), four were clinical social workers (master level), six were psychiatry residents (MDs), and two were clinical pedagogues (i.e., undergraduate degree in education with an additional two years of clinical training). All therapists were employees of community clinics (volunteered as study therapists) and study participants were treated as part of their ordinary caseload. Two (2/32) therapists had completed a two-year post-graduation CBT training program, but all other therapists had little or no previous training in CBT with the exception of those who were clinical psychologists (20/32), where basic CBT was likely part of standard education. Therapists varied in their theoretical orientation before the study, including eclectic, cognitive, psychodynamic, or family oriented. All therapists attended a two-day workshop on CBT for childhood anxiety disorders in general, and using the Coping Cat in particular. In addition, annual one-day booster workshops were offered. The workshop focused on the key treatment principles outlined in the manual and consisted of a combination of lectures, practical exercises, and answering questions. Supervision was provided by two experienced clinical psychologist with formal CBT training. During the treatment phase of the study, therapists were offered monthly two-hour group supervision. Attendance was not mandatory and between three and ten study therapists typically attended the meetings. Supervision typically involved discussions of questions raised by the study therapists in relation to patients they were currently treating and the practical application of the treatment protocol. Additional supervision was available upon request, but few therapists took advantage of this offer. Most therapists did both individual and group treatments. For GCBT, two therapists were assigned to each group.

Ratings of adherence and competence

To assess treatment fidelity, all sessions were video-recorded. A random sample of 212 sessions (13% of total number of sessions) was rated for adherence and competence. Sessions were rated using the CBT Youth Adherence and Competence scale (Bjaastad et al., 2015). The scale consists of 11 items. Adherence was rated from 0 (None) to 6 (Thorough) and competence was rated from 0 (Poor skills) to 6 (Excellent skills). The selection of rated sessions was stratified on early (1–6) and late (7–12) sessions. Two expert therapists and three non-experts rated the sessions. Inter-rater reliability of randomly selected sessions rated by all five raters (10% of all sessions rated were rated for reliability) showed excellent agreement, intraclass correlation coefficient = .96 for adherence and .90 for competence. The mean score across treatments for ICBT was M=4.06 (SD=1.08, range 1.29–5.86) for adherence and M=4.39 (SD=1.02, range 1.50–6.00) for competence. For GCBT the mean rating for adherence was M=4.54 (SD=0.95, range 1.57–5.68) and M=4.60 (SD=1.09, range 1.25–6.00) for competence. There were no significant differences between treatment conditions in adherence or competence.

Assessment

Independent evaluators (IEs) were advanced graduate students in clinical psychology, or clinicians who worked at the clinics. IEs were blind to treatment condition and conducted semi-structured diagnostic interviews at baseline, at post treatment, and at 2-year follow-up. For each assessment the IEs completed the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM- IV-TR (ADIS) (Silverman & Albano, 1996) and the Child Global Assessment of Severity (CGAS) (Shaffer et al., 1983). All assessments were videotaped. IEs were trained to reliability (Kappa=1) and had to match disorder(s) on three or more taped training interviews before being allowed to assess study participants. IEs interviewed the child and parent(s) separately and were permitted to incorporate other information as deemed appropriate. Composite diagnoses were determined in accordance with guidelines outlined by Silverman and Albano (1996). All baseline assessments were discussed anonymously and diagnoses confirmed in weekly clinic supervision by a clinical psychologist, IEs, and participating clinicians before eligible cases were assigned to a therapist. Post-treatment and follow-up assessments were determined by the IEs only.

Measures

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, child and parent versions

(Silverman & Albano, 1996) was used to assess diagnostic eligibility and response to treatment. Parents and children were interviewed separately. Parents were interviewed using the full interview and children completed the modules covering SAD, SOC, and GAD. IEs provided a composite Clinical Severity Rating (CSR) on a nine-point scale (0–8), with a CSR ≥ 4 required for clinical disorders. The diagnosis with the highest CSR determined the principal disorder. Inter-rater reliability for the anxiety diagnoses in the present study showed kappa coefficients of 1.00 for SAD, 1.00 for SOC, and 0.89 for GAD when compared to an expert evaluator’s rating of 15% of randomly selected interviews from the video recordings.

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, child and parent versions

(March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) is a 39-item self-report measure of anxiety symptoms. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never true about me), 2 (rarely true about me), 3 (sometimes true about me), and 4 (often true about me). Cronbach’s alpha was .90 for child-report and α=.89 for mother-report at baseline. The MASC has been shown to be a meaningful measure of anxiety symptoms and anxiety diagnoses among Norwegian youth (Villabø, Gere, Torgersen, March, & Kendall, 2012).

Child Behavior Checklist

(Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) is a 113-item checklist completed by a parent to obtain information of a broad range of behavioral and emotional problems. Statements are rated from 0 to 2 for how well a particular statement describes the child: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very often true). Scores are summed and the total score subdivided into an Internalizing Problem scale and Externalizing Problem scale. Multicultural norms are available for scoring of the CBCL and were applied in the present study (Achenbach et al., 2008).

Children’s Global Assessment Scale

(Shaffer et al., 1983) is a clinician-rated measure of the child’s overall functioning that considers not only emotional or behavioral problems, but also somatic problems, family and other environmental factors that may influence the youth’s daily functioning. The CGAS is rated from 1 (lowest functioning) to 100 (excellent functioning), and 70 is the cut-off for caseness. The final score used in the analyses is the average score of the independent ratings provided by clinicians who were present at the weekly case conferences. Reliability of the CGAS is acceptable (Hanssen-Bauer, Aalen, Ruud, & Heyerdahl, 2007; Shaffer et al., 1985). Based on 40 randomly selected cases, intraclass correlation (ICC) for CGAS scores in the current sample was above .90.

Questionnaire for Evaluation of Treatment

(Fragebogen zur Beurteilung der Behandlung) (Mattejat & Remschmidt, 1998) was used to evaluate treatment satisfaction and was completed by the child, parent, and therapist. The scale has different versions for the three informants. The child version consists of 20 items, parent version 21 items, and therapist version 26 items. The scale was translated from German, back-translated, and approved by the scale’s author.

Sample Size and Power

Assuming response (defined as a loss of baseline principal anxiety disorder at the end of treatment) rates of 60%, 60% and 20% for ICBT, GCBT, and WL, respectively, a 5% Type-I error, two-tailed test, and a planned total sample size of 165 (55 per group), the study was designed to detect a difference in response rates between an active treatment (ICBT or GCBT) and the control condition (WL) with 97% probability.

Missing Data

Every effort was made to collect outcomes on all participants, even those who withdrew from treatment but not from the assessments. Missingness was mainly related to study withdrawal (see Figure 1 for details). Prior to analysis, we used multiple imputation to replace missing values. SAS PROC MI was used to generate multiple data sets for both categorical (using logistic regression) and continuous (using predictive mean matching) variables. Each imputation model included all longitudinal outcome measures, assessment points, treatment indicators, and key putative moderators and mediators of outcome. Twenty imputed data sets were generated. Results were calculated using Rubin’s rules for combining imputed data sets as implemented in SAS PROC MIANALYZE.

Statistical Analysis

All randomized participants were included in analyses, in accordance with intent-totreat (ITT) principles. To examine and compare treatment effects for categorical outcomes (diagnoses), estimates of binomial proportions of responders in each treatment condition and the difference between these proportions, as well as their asymptotic standard errors, were calculated using SAS PROC FREQ and passed directly to SAS PROC MIANALYZE to derive pooled estimates over all imputed data sets (Ratitch, Lipkovich, & O'Kelly, 2013). For continuous outcomes, separate longitudinal regression models, implemented in SAS PROC MIXED, examined mean differences in each outcome between (1) the three randomized conditions (ICBT, GCBT, and WL) and (2) the two randomized treatment formats (ICBT, GCT), which included data from WL participants after they had received treatment. Each regression model included indicators of time (assessment visit), treatment condition, and all time-by-treatment interaction terms. Residual error terms were assumed to follow a meanzero, normal distribution with an unstructured covariance structure used to capture the within person correlation over time. The following covariates were also included in each regression model: age, gender, number of baseline comorbidities, and baseline ADIS CSR ratings for each of the 3 main anxiety diagnoses. All covariates were grand mean centered. The fitted models were used to report model-based mean scores at each assessment point and to make inferences about between-group comparisons at each assessment point. The sequential Dunnett test was used to control overall family-wise error rate. All statistical models were fit using version 9.4 TS Level 1M3 of SAS Statistical Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Recruitment and Retention

The Consort diagram (Figure 1) illustrates that of the 165 randomized participants, 11 (7%) stopped treatment prematurely but agreed to complete the post treatment assessments (treatment withdrawals) and 17 (10%) stopped both treatment and assessments (study withdrawals). Of these 28 participants, 8 (15%) were from WL, 16 (29%) from ICBT, and 4 (7%) from GCBT. On the basis of logistic regression analyses, pairwise comparisons indicated that participants in the ICBT group were significantly more likely to prematurely stop treatment or withdraw from the study altogether (p<.01) when compared to those in the GCBT group (OR=5.2; 95% CI, 1.6 to 16.9), see Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference in premature termination or study withdrawal rates between WL and ICBT conditions (p>.22). Five children who were randomized to the WL condition were study withdrawals, 3 children were excluded after completing the WL because an anxiety disorder was no longer their principal disorder (2 met criteria for primary depression, 1 for primary ADHD), leaving 47 children from the WL who were re-randomized to ICBT (n=28) and GCBT (n=19) following the waitlist period. The mean number of completed sessions in ICBT and GCBT was 9.5 (SD=4.3) and 10.6 (SD=3.7), respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants at baseline

| Variable | ICBT | GCBT | WL | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| CAMH Clinic | p>.97 | ||||

| Bærum | 15 (27.3) | 15 (27.3) | 15 (27.3) | 45 (27.3) | |

| Grorud | 10 (18.2) | 10 (18.2) | 9 (16.4) | 29 (17.6) | |

| Jessheim | 15 (27.3) | 15 (27.3) | 15 (27.3) | 45 (27.3) | |

| Skien | 11 (20.0) | 8 (14.6) | 9 (16.4) | 28 (17.0) | |

| Porsgrunn | 4 (7.3) | 7 (12.7) | 6 (10.9) | 17 (10.3) | |

| Referral Reason | p>.69 | ||||

| Anxiety | 30 (54.6) | 33 (60.0) | 29 (52.7) | 92 (55.8) | |

| Hyperactivity | 3 (5.4) | 4 (7.3) | 6 (10.9) | 14 (7.9) | |

| Depression | 6 (10.9) | 4 (7.3) | 2 (3.6) | 12 (7.3) | |

| Other | 16 (29.1) | 14 (25.5) | 18 (32.7) | 48 (29.1) | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 10.5 (1.6) | 10.4 (1.5) | 10.4 (1.4) | 10.5 (1.5) | p>.94 |

| Female | 24 (43.6) | 25 (45.5) | 26 (47.3) | 75 (45.5) | p>.93 |

| Living with… | |||||

| Mother | 6 (10.9) | 5 (9.1) | 9 (16.4) | 20 (12.2) | |

| Father | 4 (7.3) | 3 (5.4) | 0 (0) | 7 (4.2) | |

| Both parents | 30 (54.5) | 38 (69.1) | 31 (56.4) | 99 (60.0) | |

| Mother and partner | 9 (16.4) | 1 (1.8) | 8 (14.6) | 18 (10.9) | |

| Father and partner | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Two home family | 5 (9.1) | 8 (14.5) | 5 (9.1) | 18 (10.9) | |

| Other | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Baseline Measures | |||||

| SAD ADIS CSR | 6.7 (0.9) | 6.1 (1.1) | 6.2 (1.0) | 6.3 (1.0) | p>.13 |

| SOP ADIS CSR | 6.5 (1.2) | 6.5 (0.8) | 6.5 (1.1) | 6.5 (1.0) | p>.98 |

| GAD ADIS CSR | 6.4 (1.0) | 6.2 (0.9) | 6.9 (0.9) | 6.5 (1.0) | p>.09 |

| Child MASC (t-score) | 57.8 (11.0) | 57.2 (11.7) | 58.2 (10.5) | 57.7 (11.0) | p>.88 |

| Parent MASC | 57.2 (16.5) | 58.6 (17.1) | 56.4 (16.2) | 57.4 (16.5) | p>.79 |

| MFQ | 14.0 (13.7) | 13.7 (9.8) | 12.6 (8.3) | 13.4 (10.8) | p>.77 |

| CBCL Internalizing | 70.6 (8.6) | 72.3 (8.0) | 70.8 (10.0) | 71.2 (8.9) | p>.56 |

| CBCL Externalizing | 57.6 (11.8) | 56.3 (11.4) | 56.8 (11.9) | 56.9 (11.7) | p>.86 |

| CGAS | 50.8 (6.1) | 53.1 (5.4) | 51.1 (6.1) | 51.7 (5.9) | p>.08 |

| Baseline Comorbidity | |||||

| Any Comorbidity | 41 (74.6) | 32 (58.2) | 39 (79.9) | 112 (67.9) | p>.15 |

| MDD | 4 (7.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | 5 (3.0) | p>.15 |

| Specific phobia | 18 (32.7) | 12 (21.8) | 15 (27.3) | 45 (27.3) | p>.44 |

| ADHD | 9 (16.4) | 12 (21.8) | 10 (19.2) | 31 (19.1) | p>.77 |

| ODD | 8 (14.6) | 2 (3.6) | 2 (3.6) | 12 (7.3) | p<.04 |

| Other comorbidity | 3 (5.4) | 3 (5.4) | 6 (10.9) | 12 (7.3) | p>.44 |

| Observed Cases | |||||

| Baseline | 55 | 55 | 55 | 165 | |

| Study dropouts | 16 (29.1) | 4 (7.3) | 8 (14.6) | 28 (17.0) | p<.01 |

| Treatment withdrawals | 5 (9.1) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (7.3) | 11 (6.7) | p>.36 |

| Study withdrawals | 11 (20.0) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (7.3) | 17 (10.3) | p<.01 |

| Completed… | |||||

| Week 12 assessments | 44 (80.0) | 52 (94.5) | 51 (92.7) | 147 (89.09) | p<.03 |

| Year 2 assessments | 58 (68.2) | 54 (67.5) | NA | 112 (67.9) | p>.92 |

Note: ICBT = individual cognitive behavioral therapy; GCBT = group cognitive behavioral therapy; WL = wait list control; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; SOP = social phobia; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; MFQ = Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; CBCL Internalizing = Child Behavioral Checklist Internalizing subscale; CBCL Externalizing = Child Behavioral Checklist Externalizing subscale; CGAS = Children’s Global Assessment Scale; MDD = major depressive disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder; ODD = opposition defiant disorder.

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants by treatment condition. Only one significant between groups difference emerged. A significantly larger (p<.04) proportion of ICBT (14.6%) participants were comorbid with oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) when compared to the other two conditions, GCBT (3.6%) and WL (3.6%). Most of the participants were European/Caucasian2 (98.8%), one child was Asian (0.6%), and one was Hispanic (0.6%). The majority were referred to CAMHS clinics specifically for a possible anxiety disorder (55.8%), were male (54.5%), and lived with both biological parents in the same household (60.0%). Fourteen (8.5%) mothers and 14 (8.5%) fathers had no high-school education, 70 (42.9%) mothers and 69 (41.8%) fathers had a high-school degree, 44 (26.7%) mothers and 42 (25.5%) fathers had a college level education, and 36 (21.8%) mothers and 30 (18.2%) fathers had post college level education. Education level was not reported for 1 (0.6%) mother and 10 (6.1% fathers).

Treatment Response

The categorical primary outcome was loss of the child’s principal anxiety disorder based on the IEs ADIS interview following treatment. The proportion of responders in each condition is presented in Table 2. In the ITT analysis, the percentages of participants across the three study conditions that no longer met diagnostic criteria for their principal anxiety disorder were: 14% for WL (95% CI, 4% to 23%), 52% for ICBT (95% CI, 38% to 67%), and 65% for GCBT (95% CI, 52% to 78%). Planned pairwise comparisons, using a chi-square test, showed that both ICBT (p<.001) and GCBT (p<.001) were superior to WL. ICBT and GCBT were not significantly different from each other (p=.19). Full diagnostic recovery, defined as loss of all anxiety disorders, were 6% for WL (95% CI, 0% to 14%), 38% for ICBT (95% CI, 24% to 52%), and 56% for GCBT (95% CI, 43% to 69%). Table 2 provides detailed description of point estimates, confidence intervals, and planned comparisons for changes in diagnostic status following treatment.

Table 2.

Proportion of responders by the three treatment conditions

| Loss of… | Proportion of Responders (95% CI) | Pairwise Difference in Proportions of Responders (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WL N = 55 | ICBT N = 55 | GCBT N = 55 | WL vs. ICBT | WL vs. GCBT | ICBT vs. GCBT | |

| Primary Anxiety Diagnosis | 0.14 (0.04, 0.23) | 0.52 (0.38, 0.67) | 0.65 (0.52, 0.78) | 0.38a (0.21, 0.56) | 0.51a (0.35, 0.68) | 0.13 (−0.07, 0.33) |

| SAD Diagnosis | 0.28 (0.13, 0.44) | 0.55 (0.37, 0.73) | 0.57 (0.40, 0.74) | 0.27c (0.03, 0.50) | 0.28c (0.05, 0.51) | 0.01 (−0.24, 0.26) |

| SOP Diagnosis | 0.15 (0.01, 0.28) | 0.41 (0.21, 0.61) | 0.77 (0.60, 0.95) | 0.26c (0.02, 0.50) | 0.62a (0.40, 0.84) | 0.36b (0.09, 0.62) |

| GAD Diagnosis | 0.25 (0.09, 0.42) | 0.74 (0.58, 0.91) | 0.63 (0.43, 0.83) | 0.49a (0.26, 0.72) | 0.38b (0.12, 0.64) | −0.11 (−0.37, − 0.15) |

| All Anxiety Diagnoses | 0.06 (−0.01, 0.14) | 0.38 (0.24, 0.52) | 0.56 (0.43, 0.69) | 0.31a (0.16, 0.47) | 0.50a (0.34, 0.65) | 0.18 (−0.01, 0.38) |

<.001;

<.01;

<.05.

Note: WL = Waitlist Control; ICBT = individual cognitive behavioral therapy; GCBT = group cognitive behavioral therapy; CI = confidence interval; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; SOP = social anxiety disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder.

To evaluate whether one treatment was more effective for a specific anxiety disorder, a series of pairwise comparisons were undertaken using the same approach as that used to evaluate the categorical primary outcome. Only those participants who met baseline diagnostic criteria for a given disorder were included in these analyses. The pattern of findings for SAD, GAD, and loss of all baseline anxiety disorders was similar to that found with the categorical primary outcome; namely, both active treatments were superior to WL but not significantly different from each other (i.e., ICBT=GCBT>WL). However, a different pattern of results emerged for youth diagnosed with SOC. The percentages of participants who no longer met diagnostic criteria for SOC were: 15% for WL (95% CI, 1% to 28%), 41% for ICBT (95% CI, 21% to 61%), and 77% for GCBT (95% CI, 60% to 95%). Pairwise comparisons revealed that both ICBT (p<.03) and GCBT (p<.001) were significantly superior to WL. The pairwise comparison between the two active treatment conditions found that GCBT was significantly superior to ICBT (p<.008; see Table 2).

Additional ITT analysis of only the two active treatment conditions, but including data from the WL participants after they had received treatment, revealed a similar pattern of findings (see Table 3). Namely, the only significant difference between ICBT and GCBT was in percentage of participants who no longer met diagnostic criteria for SOC (p<.05).

Table 3.

Proportion of responders in individual and group CBT with children previously randomized to wait list included in active treatment

| Loss of… | Time Point | Proportion of Responders (95% CI) | Pairwise Difference in Proportions of Responders (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICBT N = 85 | GCBT N = 80 | ICBT vs. GCBT | ||

| Primary Anxiety Diagnosis | 12-Week | 0.54 (0.40, 0.68) | 0.61 (0.49, 0.73) | 0.07 (−0.09, 0.23) |

| 2-Year | 0.82 (0.74, 0.91) | 0.91 (0.84, 0.98) | 0.09 (−0.03, 0.20) | |

| SAD Diagnosis | 12-Week | 0.61 (0.45, 0.77) | 0.59 (0.44, 0.74) | −0.02 (−0.22, 0.18) |

| 2-Year | 0.87 (0.77, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.00) | 0.08 (−0.03, 0.20) | |

| SOP Diagnosis | 12-Week | 0.41 (0.23, 0.60) | 0.68 (0.51, 0.85) | 0.26a (0.04, 0.49) |

| 2-Year | 0.72 (0.56, 0.88) | 0.79 (0.63, 0.94) | 0.06 (−0.15, 0.28) | |

| GAD Diagnosis | 12-Week | 0.74 (0.59, 0.90) | 0.58 (0.41, 0.76) | −0.16 (−0.37, 0.05) |

| 2-Year | 0.95 (0.87, 1.00) | 0.95 (0.87, 1.00) | 0.00 (−0.11, 0.11) | |

| All Anxiety Diagnoses | 12-Week | 0.45 (0.31, 0.58) | 0.48 (0.35, 0.60) | 0.03 (−0.13, 0.19) |

| 2-Year | 0.72 (0.62, 0.82) | 0.78 (0.67, 0.89) | 0.06 (−0.08, 0.21) | |

<.03.

Note: ICBT = individual cognitive behavioral therapy; GCBT = group cognitive behavioral therapy; CI = confidence interval; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; SOP = social anxiety disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder.

Planned pairwise comparisons of the continuous outcome variables showed an inconsistent pattern of findings (see Table 4). There were no significant between group differences on the child or the parent MASC total scores (all p-values NS). For the CGAS, both ICBT and GCBT were significantly superior to WL (t=5.91, p<.001; t=6.31, p<.001, respectively), and ICBT and GCBT did not significantly differ from each other (t=-0.18, p=.86). Estimates of the effect size (Hedges’ g) on the CGAS for the two treatment conditions and WL were calculated. Effect sizes were based on the means on the CGAS, estimated from the mixed-effects model. The effect size was 1.01 (95% CI, 0.67 to 1.35) for ICBT and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.72 to 1.37) for GCBT. Tables 4 and 5 provide a detailed description of point estimates planned comparisons, and the respective effect sizes for each continuous outcome.

Table 4.

Three-group comparison of model-based means and effect size estimates at post-treatment

| Time Point | Study Group Means (SEs) | Hedges’ g Effect Size Estimates (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WL | ICBT | GCBT | WL vs. ICBT | WL vs. GCBT | ICBT vs. GCBT | ||

| Child MASC | Baseline | 57.97 (1.47) | 57.3 (11.47) | 57.63 (1.48) | NA | NA | NA |

| 12-Week | 51.95 (1.60) | 48.61 (1.48) | 48.80 (1.65) | 0.28 (0.10, 0.65) | 0.26 (0.12, 0.64) | 0.01 (−0.36, 0.39) | |

| Parent MASC | Baseline | 55.46 (2.10) | 55.04 (2.06) | 59.82 (2.10) | NA | NA | NA |

| 12-Week | 50.86 (2.45) | 47.25 (2.58) | 49.72 (2.46) | 0.20 (0.18, 0.61) | 0.06 (−0.34, 0.48) | 0.14 (−0.27, 0.56) | |

| CGAS | Baseline | 51.20 (0.70) | 51.46 (0.70) | 52.44 (0.71) | NA | NA | NA |

| 12-Week | 53.05 (1.09) | 62.52 (1.17) | 62.81 (1.10) | 1.01a (0.68, 1.35) | 1.04a (0.72, 1.37) | 0.03 (−0.31, 0.37) | |

p<.001.

Note: SE = standard error; WL = wait list control; ICBT = individual cognitive behavioral therapy; GCBT = group cognitive behavioral therapy; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; CGAS = Child Global Assessment Scale.

Means presented are model based mean estimated at each time point. The following covariates were included (grand mean centered) in each model: Child age (at baseline), gender, number of comorbid disorders, baseline ADIS CSR ratings for each target anxiety disorder.

For effect size estimates, calculations were based on between-groups differences in estimated mean scores at Week 12 divided by the pooled standard deviation of the outcome at Week 12, otherwise known as Hedges’ g (95% CI).

Table 5.

Two-group comparison of model-based means and effect size estimates at post-treatment and two-year follow-up

| Measure | Time Point | Study Group Means (SEs) | Hedges’ g Effect Size Estimates (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICBT | GCBT | ICBT vs. GCBT | ||

| Child MASC | Baseline | 57.27 (1.21) | 58.03 (1.25) | NA |

| 12-Week | 47.78 (1.40) | 48.05 (1.35) | 0.02 (−0.31, 0.35) | |

| 2-Year | 47.12 (1.18) | 45.71 (1.16) | −0.13 (−0.43, 0.16) | |

| Parent MASC | Baseline | 54.77 (1.69) | 58.91 (1.74) | NA |

| 12-Week | 45.40 (2.03) | 49.32 (1.95) | 0.23 (−0.10, 0.57) | |

| 2-Year | 42.30 (1.80) | 40.67 (1.88) | −0.10 (−0.42, 0.22) | |

| CGAS | Baseline | 51.33 (0.56) | 52.10 (0.58) | NA |

| 12-Week | 63.03 (1.04) | 62.69 (1.04) | −0.04 (−0.36, 0.28) | |

| 2-Year | 69.66 (1.34) | 72.91 (1.33) | 0.26 (−0.03, 0.56) | |

Note: ICBT = individual cognitive behavioral therapy; GCBT = group cognitive behavioral therapy; CI = confidence interval; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; CGAS = Child Global Assessment Scale.

Means presented are model based mean estimated at each time point. The following covariates were included (grand mean centered) in each model: Child age (at baseline), gender, number of comorbid disorders, baseline ADIS CSR ratings for each target anxiety disorder.

For effect size estimates, calculations were based on between-groups differences in estimated mean scores at Week 12 divided by the pooled standard deviation of the outcome at Week 12, otherwise known as Hedges’ g (95% CI).

Maintenance of gains

Treatment gains were maintained at two-year follow-up as the post treatment rates of remission were relatively stable at two-year follow-up assessment (see Table 3 for categorical and Table 5 for continuous outcomes). Table 6 presents the proportion of participants who continued to be in remission, relapse, and new remission at follow-up assessment compared to the post-treatment assessment. Very few children had relapsed by the two-year follow-up assessment (ICBT=6%, 95% CI 1% to 12% and; GCBT=4%, 95% CI 0% to 9% for primary anxiety diagnosis). In addition, a relatively large number of children continued to improve and reached remission by the end of the two-year follow-up assessment (ICBT=35%, 95% CI 22% to 48%; GCBT=35%, 95% CI 23% to 46%). Analyses of continuous measures by treatment condition revealed no additional improvement on the child MASC from posttreatment to follow-up assessment (ICBT p=.684; GCBT p=.126). On parent-report of anxiety symptoms on the MASC, GCBT continued to show significant improvement from posttreatment to two-year follow-up (t=3.57, p<.001), while no significant improvement was observed for ICBT (t=1.24, p=.216). Improvement was noted across both treatment conditions on the CGAS from post-treatment to follow-up (ICBT t=4.01, p<.001; GCBT t=6.43, p<.001). Further tests to evaluate if one treatment condition was associated with greater improvement at follow-up, were all non-significant.

Table 6.

Rates of stable remission, relapse, and new remission at two-year follow-up assessment

| Proportion of Participants (95% CI) | Pairwise Difference in Proportions of Participants (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICBT | GCBT | ICBT vs. GCBT | |

| Stable Remission Through Follow-up | |||

| Primary Anxiety Diagnosis | 0.47 (0.34, 0.61) | 0.57 (0.44, 0.69) | 0.09 (−0.07, 0.25) |

| SAD Diagnosis | 0.53 (0.37, 0.69) | 0.55 (0.40, 0.70) | 0.02 (−0.19, 0.23) |

| SOP Diagnosis | 0.38 (0.19, 0.56) | 0.59 (0.42, 0.77) | 0.21 (−0.02, 0.45) |

| GAD Diagnosis | 0.71 (0.55, 0.87) | 0.55 (0.38, 0.72) | −0.17 (−0.38, 0.05) |

| Relapse at Follow-up | |||

| Primary Anxiety Diagnosis | 0.06 (0.01, 0.12) | 0.04 (0.00, 0.09) | −0.02 (−0.10, 0.06) |

| SAD Diagnosis | 0.08 (−0.01, 0.16) | 0.04 (−0.01, 0.09) | −0.04 (−0.14, 0.06) |

| SOP Diagnosis | 0.04 (−0.03, 0.11) | 0.09 (−0.01, 0.18) | 0.05 (−0.07, 0.17) |

| GAD Diagnosis | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.08) | 0.04 (−0.03, 0.10) | 0.01 (−0.08, 0.09) |

| New Remission at Follow-up | |||

| Primary Anxiety Diagnosis | 0.35 (0.22, 0.48) | 0.35 (0.23, 0.46) | 0.00 (−0.16, 0.15) |

| SAD Diagnosis | 0.34 (0.17, 0.51) | 0.41 (0.26, 0.56) | 0.07 (−0.13, 0.27) |

| SOP Diagnosis | 0.34 (0.18, 0.50) | 0.19 (0.05, 0.33) | −0.15 (−0.37, 0.07) |

| GAD Diagnosis | 0.23 (0.08, 0.38) | 0.40 (0.23, 0.57) | 0.17 (−0.05, 0.38) |

Note: ICBT = individual cognitive behavioral therapy; GCBT = group cognitive behavioral therapy; CI = confidence interval; SAD = separation anxiety disorder; SOP = social anxiety disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder.

Clinically significant change

Using normative information to judge clinically meaningful change (Kendall et al, 1999), the findings indicated that all children were, at baseline, in the clinical range of the CGAS (i.e., CGAS<70) indicating marked functional impairment. The percent of children who moved out of the clinical range (into the non-clinical range) on functional impairment (CGAS) was 22.0% at post treatment and 50.1% at follow-up. Children in ICBT and GCBT did not differ significantly in the percentage who moved into the non-clinical range on the CGAS at post treatment or at follow-up.

Treatment satisfaction

Children, parents, and therapists rated their overall satisfaction with the treatment. Satisfaction with the treatment was good across informants. Mothers reported significantly greater overall satisfaction with ICBT (M=3.39, SD=.44) compared to GCBT (M=3.09, SD=.46. t=3.51, p<.001). Treatment satisfaction did not differ significantly between ICBT and GCBT based on child (ICBT M=3.23, SD=.59, GCBT M=3.11, SD=.60, t=1.13, p=.26), father (ICBT M=3.14, SD=.48, GCBT M=3.01, SD=.46, t=1.29, p=.20), and therapist (ICBT M=2.80, SD=.32, GCBT M=2.68, SD=.43, t=1.30, p=.20) report.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the effectiveness and two-year follow-up of CBT for pediatric anxiety disorders. Similar to the large number of prior efficacy studies, current results provide evidence for the effectiveness of CBT when provided by clinicians in community mental health clinics. These findings underscore that CBT as a treatment for pediatric anxiety can be effectively delivered by clinicians with little prior training in CBT. Importantly, the overall observed response rates were comparable to those found in randomized clinical efficacy trials. However, unlike several prior outcome studies, (e.g., Walkup et al., 2008) participants who received treatment continued to improve between posttreatment and two-year follow-up. This study also evaluated two formats of CBT delivery, individual and group. Both individual and group CBT were superior to the waitlist comparison condition following acute-care and in general, there were few significant differences between the two formats. One important exception, children diagnosed with SOC responded better to group CBT than to individual CBT.

Response rates from previous effectiveness trials have been inconsistent. Some studies reported results comparable to those observed in efficacy trials (e.g., Nauta, Scholing, Emmelkamp, & Minderaa, 2003; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010), whereas others found much lower response rates (e.g., Bodden et al., 2008; Wergeland et al., 2014). For example, Wergeland and colleagues’ (2014) effectiveness study used a similar design and treated Norwegian children in community mental health clinics. However, their reported outcomes were not as favorable, with 35% of children no longer meeting criteria for their principal anxiety disorder at post-treatment and 23% showing full diagnostic recovery post-treatment. The recovery rate did increase to 33% at follow-up but remained lower than what was observed in the current study. One potential explanation for the observed differences may be related to the protocols evaluated. The protocol evaluated by Wergeland and colleagues, Friends for Life (Barrett, 2004), does not include in-session exposures. Rather, exposures are negotiated as specific homework exercises. In contrast, the protocol evaluated in the present study emphasizes in-session exposures as a key component of the treatment. Prior work has shown that significant clinical improvement follow the introduction of exposure tasks during therapy (Peris et al., 2015) and are essential to treatment success (Bouchard, Mendlowitz, Coles, & Franklin, 2004; Hudson, 2005; Peterman, Carper, & Kendall, 2016; Rapee, Wignall, Hudson, & Schniering, 2000; Öst, Svensson, Hellstrom, & Lindwall, 2001). Assigning exposures solely as a homework exercise as opposed to a task to be completed under the guidance of the therapist in session, means that it is more difficult to know whether the child actually completed the exposure tasks and how well they were done. This in turn may lead to less favorable treatment outcomes.

Treatment gains were maintained at two-year follow-up and rates of remission were relatively stable. Relapse rates were encouragingly low and a high percentage of nonresponders at post treatment achieved remission of their primary anxiety disorders two years later. These findings are consistent with prior studies with shorter (Bodden et al., 2008; Nauta et al., 2003; Wergeland et al., 2014) as well as longer follow-up periods (Kendall, Safford, Flannery-Schroeder, & Webb, 2004) supporting the durability of treatment effects. Maintenance of treatment gains were noted on child self-report, but no additional improvement was observed at follow-up. However, both parent ratings of anxiety symptoms and therapist ratings of functional outcomes continued to improve from post-treatment to follow-up.

Much of the evidence-base for ESTs for childhood anxiety disorders come from North-American studies and studies from other countries have shown poorer outcomes (Weisz et al., 2013). Patient characteristics relevant for treatment outcome may differ not only between efficacy and effectiveness studies, but also across different nationalities. Previous comparisons of children treated in university-based research clinics and community clinics have found important differences, for example in socio-demographic characteristics, anxiety severity and comorbid externalizing symptoms (Ehrenreich-May et al., 2011; Southam-Gerow et al., 2003; Villabø, Cummings, Gere, Torgersen, & Kendall, 2013), but also important similarities (Villabø et al., 2013). Similarly, the present sample had higher clinical severity ratings of their anxiety disorders (ADIS CSR) and parent-reported internalizing symptoms compared to participants in the largest treatment trial to date for pediatric anxiety disorders (Walkup et al., 2008). Yet, response rates between the two studies were comparable.

The present study found both individual and group CBT to be effective, with no overall significant differences between them, lending further support to the effectiveness for both formats of delivery (de Groot, Cobham, Leong, & McDermott, 2007; FlannerySchroeder & Kendall, 2000; Lau et al., 2010; Liber et al., 2008; Wergeland et al., 2014). Of particular relevance for dissemination of ESTs, the present results suggest that CBT can be effectively delivered by non-specialist therapists with little prior training in CBT (and working in “real-world” settings). Therapists only received a two-day workshop before the study, which is less than in some other effectiveness trials (Barrington et al., 2005; Bodden et al., 2008; Wergeland et al., 2014). Therapists in university-based research (efficacy) settings are typically doctorial trainees or doctoral -level psychologists specialized in the treatment delivered (e.g., Kendall et al., 2008; Walkup et al., 2008), whereas therapists in community care (effectiveness) settings, such as in the present study, represent multiple professions and treat a clinically heterogeneous population (Smith et al., 2017; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010; Wergeland et al., 2014). Such differences can impact treatment delivery, although a recent study found more similarities than differences in treatment delivery of manual-based ICBT across research and practice settings (Smith et al., 2017). Treatment integrity was comparable to some effectiveness trials (e.g., Wergeland et al., 2014), but lower than other both effectiveness and efficacy trials using the same treatment protocol (e.g., Kendall et al., 1997; Kendall et al., 2008; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010). These results may directly address therapist skepticism regarding the ecological validity of efficacy trials. Ensuring that treatment evaluations are relevant to practitioners is key to successful dissemination of ESTs in non-research settings (Antony, 2005).

Findings to date have indicated that although youth with social anxiety respond positively to CBT, their outcomes are not as favorable as those for youth with SAD or GAD. An additional important finding of the current study is that SOC as the principal disorder moderated effectiveness of ICBT and GCBT: children with SOC responded better when treated in the group format than in the individual format. This finding is contrary to some previously reported inconsistent outcomes (Liber et al., 2008; Manassis et al., 2002; Wergeland et al., 2014). The modifications made to the traditional group format in the current study may in part explain these differences. Introducing the child to treatment in individual sessions with the therapist before entering the group may be a key factor to successful outcomes for youth with SOC. The presence of comorbid disorders may compromise treatment response. Comorbid ODD was more frequent among children in ICBT. Cooccurrence of SOC and ODD was low (only 2% of children with SOC had comorbid ODD, compared to 7% of children with SAD and 11% of children with GAD) and it is less likely that differences in comorbid disorders can explain the more favorable outcomes for children with SOC in GCBT compared to ICBT. In addition to GCBT being more effective than ICBT for children with SOC, attrition rates were significantly lower in the group format. Taken together, these results suggest that the modified group format may be more acceptable to anxious youth and particularly more suitable for children with SOC. However, at the two-year follow-up there were no significant between-group differences in outcomes between the diagnostic groups and children with SOC who had received individual or group CBT. This suggests that children who receive individual CBT are likely to catch up to those who received group CBT. Treatment gains were maintained and additional improvement was observed over the course of the follow-up period for a significant portion of children in both treatment groups. The difference in speed of recovery during acute treatment in children with SOC, however, has important implications. Results from the current study suggest that the modified group CBT format will lead to a more rapid response when compared to traditional individual-based CBT.

More children who received the active treatment lost their principal anxiety diagnosis and improved their overall functioning compared to children on the waitlist. However, there were no differences between the groups in change in anxiety symptoms, neither by youth nor by parent report. There are several possible explanations. As part of the treatment, children and parents learn about anxiety symptoms and how to recognize them which may raise their awareness of such symptoms. As a consequence, they may actually report more symptoms at post-treatment. In addition, given that children are taught to expect some symptoms to continue, but to use them as cues to not avoid, self-report of symptoms may persist even when functioning improves.

Potential limitations merit consideration. CBT was compared to a waitlist and not to treatment as usual (TAU), and such a comparison may inflate the observed treatment effects. Relatedly, using a waitlist comparison condition eliminates the opportunity to make comparisons at follow-up (unethical to make treatment-seeking children wait two years). It is important to compare treatments, such as CBT, to standard care. Some evidence showed limited support for CBT against TAU for child anxiety disorders in effectiveness studies (Barrington et al., 2005; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010), but a closer look (e.g., Southam-Gerow et al., 2010) identified that (a) TAU youth received multiple mental health services and (b) the exposure portion of CBT was not done with full integrity. Studies were also underpowered to detect anything but large differences in effect sizes. On the other hand, using TAU as a comparison condition is not without its challenges (Öst, 2014): TAU changes over time, treatment duration may differ between TAU and the treatment of interest, and treatment integrity is typically not assessed with TAU. In the present study, we did not observe significant differences in treatment response between ICBT and GCBT. However, as this twogroup comparison was a secondary question in the study, it was not adequately powered to detect small differences between the two active treatments. Another limitation in the present study is the fact that we do not know what other services children received during the followup period. The degree to which additional services received may have contributed to the positive findings is unknown.

Future directions

Based on the present findings, CBT for pediatric anxiety disorders can be implemented effectively when delivered in individual and group formats. However, the group format was associated with lower treatment attrition and may thus be more feasible in community settings. The adapted group format may result in more rapid improvement for youth with SOC and merits consideration for this group. Future implementation efforts need to consider more feasible ways of providing clinical supervision to improve attendance and possibly treatment outcome.

Youth vary in the speed with which they show a positive treatment response. Future studies should examine factors that influence the speed of recovery for children with anxiety disorders and what forces contribute to a speedier recovery for subgroups of children. Such a goal may be important when making recommendations about formats of delivery, such as modified group CBT for children with SOC. A critical, but as yet unanswered question is what treatments to offer a child who does not respond to know to be effective interventions. How can we best sequence treatments by augmenting or altering them to provide more effective services to those who do not respond to current best-practice protocols?

Acknowledgments

Philip C. Kendall receives royalties for the publication of materials for the treatment of anxiety in youth. Simon-Peter Neumer receives royalties for he publication of the Coping Cat Manual.

Phillip C. Kendall received funding for this article from the NIH, R01HD080097

Footnotes

For waitlist participants randomized to treatment following the waitlist period, their 12-week post waitlist assessment served as the baseline assessment for all analyses involving the active treatment conditions.

Ethnicity was determined based on country of origin of the child’s parents.

Contributor Information

Marianne A. Villabø, Akershus University Hospital.

Martina Narayanan, University College London.

Scott N. Compton, Duke University Medical Center.

Philip C. Kendall, Temple University.

Simon-Peter Neumer, Center for Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

References

- Achenbach TM, Becker A, Dopfner M, Heiervang E, Roessner V, Steinhausen HC, Rothenberger A. Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: Research findings, applications, and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49(3):251–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Anxiety Disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(2):267–283. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000246070.23695.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, D.C: Author; 2000. text rev. ed. [Google Scholar]

- Antony MM. Five strategies for bridging the gap between research and clinical practice. the Behavior Therapist. 2005;28(7):162–163. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett PM. FRIENDS for Life: Group leaders' manual for children. Bowen Hills, Queensland: Australian Academic Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington J, Prior M, Richardson M, Allen K. Effectiveness of CBT Versus Standard Treatment for Childhood Anxiety Disorders in a Community Clinic Setting. Behaviour Change. 2005;22(1):29–43. doi: 10.1375/bech.22.1.29.66786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bjaastad JF, Haugland BSM, Fjermestad KW, Torsheim T, Havik OE, Heiervang ER, Öst L-G. Competence and Adherence Scale for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CASCBT) for Anxiety Disorders in Youth: Psychometric Properties. Psychological Assessment. 2015 doi: 10.1037/pas0000230. No Pagination Specified. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodden DHM, Bögels SM, Nauta MH, De Haan E, Ringrose J, Appelboom C, … Appelboom-Geerts KCMMJ. Child Versus Family Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in Clinically Anxious Youth: An Efficacy and Partial Effectiveness Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(12):1384–1394. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318189148e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard S, Mendlowitz SL, Coles ME, Franklin M. Considerations in the use of exposure with children. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2004;11(1):56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Compton SN, Peris TS, Almirall D, Birmaher B, Sherrill J, Kendall PC, … Albano AM. Predictors and moderators of treatment response in childhood anxiety disorders: Results from the CAMS trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(2):212–224. doi: 10.1037/a0035458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Angold A, Shanahan L, Costello E. Longitudinal patterns of anxiety from childhood to adulthood: The Great Smoky Mountains study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(1):21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot J, Cobham V, Leong J, McDermott B. Individual Versus Group Family-Focused Cognitive–Behaviour Therapy for Childhood Anxiety: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41(12):990–997. doi: 10.1080/00048670701689436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich-May J, Southam-Gerow MA, Hourigan SE, Wright LR, Pincus DB, Weisz JR. Characteristics of anxious and depressed youth seen in two different clinical contexts. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:398411. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery-Schroeder E, Choudhury MS, Kendall PC. Group and individual cognitivebehavioral treatments for youth with anxiety disorders: 1-year follow-up. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29(2):253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery-Schroeder E, Kendall PC. Group and individual cognitive-behavioral treatments for youth with anxiety disorders: A randomized clinical trial. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24(3):251–278. [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen-Bauer K, Aalen O, Ruud T, Heyerdahl S. Inter-rater reliability of clinician-rated outcome measures in child and adolescent mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;34:504–512. doi: 10.1007/s10488007-0134-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes B. Can it work? Does it work? Is it worth it? : The testing of healthcare interventions is evolving. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 1999;319(7211):652–653. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollon SD, Beck AT. Cognitive-behavioral therapies. In: Lambert MJ, editor. Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. 6. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2013. pp. 393–442. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL. Mechanisms of change in cognitive behavioral therapy for anxious youth. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005;12:161–165. doi: 10.1093/clipsy/bpi019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, Rapee RM, Lyneham HJ, McLellan LF, Wuthrich VM, Schniering CA. Comparing outcomes for children with different anxiety disorders following cognitive behavioural therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;72:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AC, James G, Cowdrey FA, Soler A, Choke A. Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;(6):CD004690. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004690.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Flannery-Schroeder E, Panichelli-Mindel SM, Southam-Gerow M, Henin A, Warman M. Therapy for youths with anxiety disorders: a second randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(3):366–380. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Hudson JL, Gosch E, Flannery-Schroeder E, Suveg C. Cognitivebehavioral therapy for anxiety disordered youth: A randomized clinical trial evaluating child and family modalities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(2):282–297. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Martinsen KD. Mestringskatten - Gruppemanual (Coping Cat -manual for groups) Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Martinsen KD, Neumer S-P. Mestringskatten (Coping Cat). Terapeutmanual. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Safford S, Flannery-Schroeder E, Webb A. Child anxiety treatment: outcomes in adolescence and impact on substance use and depression at 7.4-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):276–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CM, Read KL, Klugman J, Kendall PC. Cognitive behavioral therapy for youth with social anxiety: Differential short and long-term treatment outcomes. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(2):210–215. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau W-y, Chan CK-y, Li JC-h, Au TK-f. Effectiveness of group cognitive-behavioral treatment for childhood anxiety in community clinics. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(11):1067–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liber JM, Van Widenfelt BM, Utens EM, Ferdinand RF, Van der Leeden AJ, Van GW, Treffers PD. No differences between group versus individual treatment of childhood anxiety disorders in a randomised clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2008;49(8):886–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manassis K, Mendlowitz SL, Scapillato D, Avery D, Fiksenbaum L, Freire M, … Owens M. Group and individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders: a randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(12):1423–1430. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200212000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen KD, Aalberg M, Gere M, Neumer SP. Using a structured treatment, Friends for Life in Norwegian outpatient clinics: results from a pilot study. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. 2009;2(1):10–19. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X08000160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattejat F, Remschmidt H. Fragebögen zur Beurteilung der Behandlung (FBB) Göttingen: Hogrefe; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nauta MH, Scholing A, Emmelkamp PM, Minderaa RB. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for children with anxiety disorders in a clinical setting: no additional effect of a cognitive parent training. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(11):1270–1278. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000085752.71002.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst LG. The efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;61:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst LG, Svensson L, Hellstrom K, Lindwall R. One-Session treatment of specific phobias in youths: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(5):814–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, Compton SN, Kendall PC, Birmaher B, Sherrill J, March J, … Piacentini J. Trajectories of change in youth anxiety during cognitive-behavior therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(2):239–252. doi: 10.1037/a0038402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman JS, Carper MM, Kendall PC. Testing the Habituation-Based Model of Exposures for Child and Adolescent Anxiety. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2016:1–11. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1163707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Wignall A, Hudson JL, Schniering CA. Treating anxious children and adolescents: An evidence-based approach. Canada: New Harbinger; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ratitch B, Lipkovich I, O'Kelly M. Combining analysis results from multiply imputed categorical data. Paper presented at the PharmaSUG; Chicago, IL. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds S, Wilson C, Austin J, Hooper L. Effects of psychotherapy for anxiety in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32(4):251–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SJ, Hoagwood K. Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: What matters when? Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1190–1197. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) Archives of General Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–1231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S. A children's global assessment scale (CGAS) (for children 4 to 16 years of age) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21(4):747–748. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child Version. San Antonio, TX: The Psychologial Corporation/Graywind Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MM, McLeod BD, Southam-Gerow MA, Jensen-Doss A, Kendall PC, Weisz JR. Does the delivery of CBT for youth anxiety differ across research and practice settings? Behavior Therapy. 2017;48(4):501–516. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Weisz JR, Chu BC, Mcleod BD, Gordis EB, Connor-Smith JK. Does cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety outperform usual care in community clinics? An initial effectiveness test. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Weisz JR, Kendall PC. Youth with anxiety disorders in research and service clinics: examining client differences and similarities. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:375–385. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan AJ, Kendall PC. Fear and Missing Out: Youth Anxiety and Functional Outcomes. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2016;23(4):417–435. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villabø MA, Cummings CM, Gere MK, Torgersen S, Kendall PC. Anxious youth in research and service clinics. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villabø MA, Gere MK, Torgersen S, March J, Kendall PC. Diagnostic efficiency of the child and parent versions of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:1–11. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.632350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, … Kendall PC. Cognitive Behavioral therapy, Sertraline, or a Combination in Childhood Anxiety. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(26):2753–2766. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Hawley KM, Jensen-Doss A. Performance of evidence-based youth psychotherapies compared with usual clinical care: A multilevel meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(7):750–761. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Sandler IN, Durlak JA, Anton BS. Promoting and protecting youth mental health through evidence-based prevention and treatment. American Psychologist. 2005;60(6):628–648. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Weiss B, Donenberg GR. The lab versus the clinic: Effects of child and adolescent psychotherapy. American Psychologist. 1992;47(12):1578–1585. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.12.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wergeland GJH, Fjermestad KW, Marin CE, Haugland BSM, Bjaastad JF, Oeding K, … Heiervang ER. An effectiveness study of individual vs. group cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders in youth. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;57:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]