Abstract

In the United States, does growing up in a poor household cause negative developmental outcomes for children? Hundreds of studies have documented statistical associations between family income in childhood and a host of outcomes in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. Many of these studies have used correlational evidence to draw policy conclusions regarding the benefits of added family income for children, in particular children in families with incomes below the poverty line. Are these conclusions warranted? After a review of possible mechanisms linking poverty to negative childhood outcomes, we summarize the evidence for income’s effects on children, paying particular attention to the strength of the evidence and the timing of economic deprivation. We demonstrate that, in contrast to the nearly universal associations between poverty and children’s outcomes in the correlational literature, impacts estimated from social experiments and quasi-experiments are more selective. In particular, these stronger studies have linked increases in family income to increased school achievement in middle childhood and to greater educational attainment in adolescence and early adulthood. There is no experimental or quasi-experimental evidence in the United States that links child outcomes to economic deprivation in the first several years of life. Understanding the nature of socioeconomic influences, as well as their potential use in evidence-based policy recommendations, requires greater attention to identifying causal effects.

Keywords: poverty, family stress, family investments, causal effects

INTRODUCTION

The term poverty brings to mind many images and has been used to describe contrasting contexts of scarcity. Poverty typically refers to a lack of economic resources but is sometimes defined more broadly as social exclusion. Mention of poverty often evokes images of poor children from economically developing countries, for whom family life consists of struggles to survive on little, if any, consistent income. Conditions of such severe economic deprivation can compromise children’s basic health and development. Yet, even in a nation as wealthy as the United States, poverty characterizes the living conditions of a substantial number of its children. The overall economic conditions of the United States have cycled between growth and recession, but even extensive economic growth has failed to lift millions of children out of poverty.

Measuring poverty in terms of economic resources is complicated because it requires defining both the types of economic resources that should be counted as income and the minimum threshold below which families have insufficient economic resources. In the 1960s, the US federal government developed a method for generating a dollar amount that, if greater than annual income, could be used to designate a family as poor. The resulting definition of poverty has been used for both determining social program eligibility and tracking trends in poverty rates.

In 2014, approximately 15.5 million US children—more than one in five—lived in poor families (DeNavas-Walt & Proctor 2015), meaning that their family income was less than approximately $24,000 for a family of two parents and two children. Since the 1960s, child poverty rates have ranged between 14% and 22%, with higher rates of poverty occurring during periods of economic decline. But this average masks important differences: Poverty rates are higher for younger than for older children, and rates for children of color are nearly 2.5 times higher than those for white children. Most US children who experience poverty do so for a short time, usually only a year or two out of their childhood. However, nearly 10% of children experience persistent poverty throughout childhood (Ratcliffe & McKernan 2012).

Developmental psychology has a long-standing interest in understanding how conditions of economic scarcity affect developmental processes. Part of this attention is driven by a desire to understand how variation in child-rearing environments and experiences gives rise to differences in child development; another part comes from a desire to improve the life chances of economically disadvantaged children by developing better social policies and programs. The existing body of research thus tries to describe both the extent to which poverty affects children and the processes behind these influences.

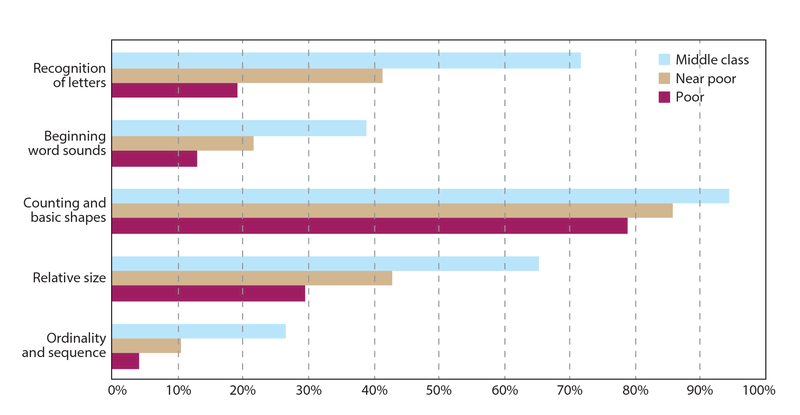

Correlational evidence shows that poor children fare worse than their more affluent peers, especially with respect to schooling and educational outcomes. Poor children begin formal schooling well behind their more affluent peers in terms of classroom and academic skills, and they never close these gaps during subsequent school years. On average, poor US children have lower levels of kindergarten reading and math skills than their more economically advantaged peers (Figure 1). Moreover, when compared with individuals whose families had incomes of at least twice the poverty line during their early childhood, adults who were poor as children completed two fewer years of schooling, earned less than half as much, worked far fewer hours per year, received more food stamps, and were nearly three times as likely to report poor health (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Rates of kindergarten proficiencies for poor, near-poor, and middle-class children, calculated by the authors from data collected by the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten from 1998 to 1999. Poor children belong to a family with income below the official US poverty threshold. Near-poor children belong to a family with income between one and two times the poverty line. Middle-class children belong to a family with income greater than twice the poverty line.

Table 1.

Adult (age 30–37) outcomes by poverty status between the prenatal year and age five

| Early childhood income below the official US poverty line (mean or percent) | Early childhood income between one and two times the poverty line (mean or percent) |

|---|---|

| 11.8 years | 12.7 years |

| $17,900 | $26,800 |

| 1,512 | 1,839 |

| $896 | $337 |

| 13% | 13% |

| 26% | 21% |

| 50% | 28% |

Earnings and food stamp values are in 2005 dollars.

Table based on data presented in Duncan et al. (2010).

Such large differences in life chances raise the possibility that poverty itself plays an influential role in shaping development. However, poverty is associated with a constellation of disadvantages that may themselves be harmful to children, including low levels of parental education and living with a single parent. Indeed, sociologists have long argued for the importance of socioeconomic status—the social status and prestige that is derived from a wide set of economic and social conditions—rather than parental income alone. Thus, it is critical to determine whether poverty itself affects development or whether other, correlated aspects of social disadvantage and status are key. Doing so will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how environments shape human development and strengthen our capacity to develop policies, programs, and interventions that support healthy physical and psychological development. For this reason, we focus in this review on characterizing the ways in which poverty and the living conditions related to poverty affect children’s development. Although we recognize the rich tradition of descriptive studies that characterize the life chances of poor children, we highlight findings from studies that can identify the causal effects of economic disadvantage on child development.

In suggesting that more attention be paid to the causal nature of the associations, we are primarily interested in probabilistic, rather than deterministic, causal associations. Poverty does not always affect all families, or even affect all families that experience negative outcomes from poverty, in the same way. Poverty is best understood as an insufficient, nonredundant part of a condition, which is itself unnecessary but is sufficient for the occurrence of the effect (Mackie 1974). A good analogy is a piece of paper and a match causing a fire. The match and paper are both nonredundant and together give rise to a causal chain of events that leads to the creation of fire. These factors do not constitute the only way in which fire can be created, nor can either alone create fire. However, we would agree that both the match and the paper are causal agents within a condition that makes fire. Thus, we consider family poverty or low income to be part of a sufficient constellation of related factors that create conditions which cause adverse family and child outcomes (see also Cook 2014).

What are the important conditions that, in combination with poverty, are the key causal agents of adverse outcomes? These conditions are best understood by considering the downstream effects of income on family processes. For example, a bag containing a thousand dollars that sits in a family’s closet would not have a causal effect on children’s outcomes. However, if the money is used to pay overdue bills or buy more nutritious food and thus reduces the parent’s psychological distress, then we would identify income as a causal agent in the condition of poverty alleviation. This type of causal thinking is important because it helps us to consider whether a policy that increases family income but does not directly target other characteristics of the family environment would enhance child and adult development.

An understanding of how the timing of poverty intersects with developmental processes is particularly important in considering how poverty shapes child development. Few studies focus on the timing of economic hardship across childhood and adolescence, in part because longitudinal studies rarely track children and their economic contexts across a variety of childhood stages. However, emerging research in neuroscience and developmental psychology suggests that poverty early in a child’s life may be particularly harmful. Not only does the astonishingly rapid development of young brains leave children sensitive and vulnerable to environmental conditions during this stage of development, but the family context dominates their everyday lives (as opposed to schools or peers, which have a greater effect on older children). For this reason, we focus our review of existing literature not only on whether poverty affects children but also on whether effects differ as a function of the developmental timing of economic deprivation.

Although our review focuses specifically on poverty, we use the terms poverty and low income synonymously. The official US poverty thresholds ensure consistency in tracking poverty rates over time and are used to determine eligibility for many means-tested programs, but there is no evidence that these precise dollar thresholds meaningfully differentiate families’ economic needs. Indeed, evidence suggests that improving the incomes of families both just below and just above the poverty line will have positive effects similar to those of pushing families across the thresholds. However, income increases do appear to matter more for lower- than for higher-income children. This has been demonstrated in studies considering links between income and children’s development across a broader spectrum of the income distribution (e.g., Loken et al. 2012). Accordingly, our review focuses on theoretical and empirical evidence of the effects of low family incomes on children rather than on how differences in income affect children residing in middle class or wealthy families.

WHY POVERTY MAY HINDER HEALTHY DEVELOPMENT

What are the consequences of growing up in a poor household? Economists, sociologists, developmental psychologists, and neuroscientists emphasize different pathways by which poverty can influence children’s development. The three main theoretical approaches describing these causal processes are the family and environmental stress perspective, the resources and investment perspective, and the cultural perspective. In addition, neuroscience is beginning to provide a fourth approach by documenting functional and structural differences in brain architecture that correlate with both family economic conditions and child development. These frameworks are grounded in different disciplinary backgrounds and vary in the extent to which they focus on socioeconomic status (SES) in general rather than on income, poverty, or any other single component of SES (e.g., parental education, occupational prestige). Nevertheless, these frameworks overlap and are complementary. Although developed primarily in the United States, each theory has cross-national and cross-cultural applications.

Family and Environmental Stress Perspective

Economically disadvantaged families experience more stressors in their everyday environments than do more affluent families, and these disparities may affect children’s development (Evans 2004). The family stress model was first developed by Glen Elder (1974; Elder et al. 1985) to explain the influence of economic loss during the Great Depression on children. Other researchers have further developed this model and applied it to families facing sudden economic downturn in rural farming communities (Conger & Elder 1994) and to single parent families (Brody & Flor 1997), as well as to ethnically diverse urban families (Mistry et al. 2002).

According to this perspective, poor families face significant economic pressure as they struggle to pay bills and purchase important goods and services, and they are thus forced to cut back on daily expenditures. This economic hardship is coupled with other stressful life events that are more prevalent in the lives of poor than nonpoor families and creates high levels of psychological distress, including depressive and hostile feelings, in poor parents (Kessler & Cleary 1980, McLeod & Kessler 1990). Psychological distress spills over into marital and coparenting relationships. As couples struggle to make ends meet, their interactions tend to become more hostile and conflicted. This leads them to withdraw from each other (Brody et al. 1994, Conger & Elder 1994). Parents’ psychological distress and conflict, in turn, are linked to parenting practices that are, on average, more punitive, harsh, inconsistent, and detached and less nurturing, stimulating, and responsive to children’s needs. Such lower-quality parenting elevates children’s physiological stress responses and ultimately harms children’s development (McLoyd 1990).

Although, historically, work in this field has focused on the family as the primary conduit of stress, theoretical and empirical work conducted in the past two decades has extended this perspective to consider stress in the broader environment. Compared with their more affluent peers, poor children are more likely to live in housing that is crowded, noisy, and characterized by structural defects such as a leaky roof, rodent infestation, or inadequate heating (Evans 2004, Evans et al. 2001). Poor families are more likely to reside in neighborhoods characterized by high rates of violence and crime and such other neighborhood risk factors as boarded-up houses, abandoned lots, and inadequate municipal services.

The schools that low-income children attend are more likely to be overcrowded and have structural problems (e.g., excessive noise and poor lighting and ventilation) compared with the schools attended by more affluent children. Economically disadvantaged children are also exposed to higher levels of air pollution from parental smoking, traffic, and industrial emissions (Clark et al. 2014, Miranda et al. 2011). These environmental conditions in the lives of low-income children create physiological and emotional stress that may impair socioemotional, physical, cognitive, and academic development (Evans 2004). For example, childhood poverty heightens a child’s risk for lead poisoning, which has been linked to ill health, problem behavior, and neurological disadvantages that may persist through adolescence and beyond (Grandjean & Landrigan 2006).

Evidence from the field of psychoneuroimmunology suggests that the experience of chronic elevated physiological stress responses may interfere with the healthy development of children’s stress response system as well as the regions of the brain responsible for self-regulation. Researchers have documented the harmful effects of such stress on animal brain development. Exposure to stress and the elevation of stress hormones such as cortisol negatively influence animals’ cognitive functioning, leading to impairments in brain structures such as the hippocampus, which is important for memory (McEwen 2000). Nonexperimental studies have found that low-income children have significantly higher levels of stress hormones than their more advantaged counterparts and that early childhood poverty is associated with increased allostatic load, a measure of physiological stress (Lupien et al. 2001, Turner & Avison 2003).

These higher levels of physiological stress relate to decreased cognitive and immunological functioning; the latter has long-term implications for a host of inflammatory diseases later in life (Miller et al. 2011). For example, recent work has linked the body’s stress response system to brain regions that support cognitive skills, such as executive functioning and self-regulation (Blair et al. 2011). The same study also found that heightened salivary cortisol, an indicator of elevated stress, partially accounts for the association between poverty on the one hand and parenting and children’s executive functioning on the other (Blair et al. 2011). Thus, disparities in stress exposure and related stress hormones may partially explain why poor children have lower levels of academic achievement, as well as poorer health later in life.

An emerging body of literature within the family stress perspective suggests that there are important individual differences in children’s susceptibility to stressful environmental influences, which may affect how income impacts children’s development (e.g., Raver et al. 2013). Ellis et al. (2011) argue that children differ in their sensitivity to environmental contexts for biological or physiological reasons, such that some children are more reactive to both positive and negative environments than other children. This framework, which is termed differential susceptibility, raises the question of whether children who are more susceptible to contextual influences are more likely to be affected by either the adversity created by poverty or the positive environment created by affluence. Empirical support for such an association is found in a small number of studies that consider how cortisol, a measure of temperamental reactivity, interacts with poverty to predict children’s executive functioning skills (Obradović et al. 2016, Raver et al. 2013). However, additional research is needed to more fully understand differential sensitivity to environments and how this may interact with poverty to affect children.

Although the biological links between low income and stress are compelling, no methodologically strong study has linked poverty and prolonged elevated stress reactions in children. Some quasi-experimental studies have examined these connections in mothers. A study of the expansions of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which provides refundable tax credits to low-income working families, used data from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Survey (Evans & Garthwaite 2014) to determine whether increased EITC payments were associated with improvements in maternal health. Between 1993 and 1996, the generosity of the EITC increased sharply, particularly for mothers with two or more children. If income matters for maternal stress, we should see a bigger improvement for children and mothers in low-income families with two children when compared to low-income mothers with a single child. Indeed, the study found that, when compared with mothers with just one child, low-income mothers with two or more children reported larger improvements in mental health, as well as reductions in stress-related biomarkers. An earlier study of the effects of increases in the Canadian Child Benefit, which is similar to a tax credit, also found improvements in maternal mental health among low-income women (Milligan & Stabile 2011).

The family stress perspective has seen major conceptual and empirical advances in the past two decades. A narrow focus on parental mental health and parenting has been extended to incorporate additional stressors that poor children encounter in their everyday environments. In addition, neurobiological evidence has begun to document the potential harmful effects of chronic elevated stress on children’s development. Increasingly methodologically rigorous studies suggest linkages between expansion of income supports and reductions in maternal stress. We expect that theoretical and empirical research will continue to benefit from an explosion in neuroscience-based findings shedding light on connections among economic resources, physiological stress responses, behavior, and development.

Resource and Investment Perspective

Although pioneered and championed by economists, household production theory has played a central role in how social scientists and developmental psychologists conceive of family influences on child development. Whereas psychologists have focused on how parent–child interactions affect developmental processes, economists have challenged scholars to think about the many ways parents use economic resources to support healthy development. Gary Becker’s (1991) A Treatise on the Family posits that child development is produced from a combination of endowments and parental investments. Endowments include genetic predispositions and the values and preferences that parents instill in their children. Parents’ preferences, such as the importance they place on education and their orientation toward the future, combined with their resources, shape parental investments.

Economists argue that time and money are the two basic resources that parents draw upon when they invest in their children. For example, investments in high-quality child care and education, housing in good neighborhoods, and rich learning experiences enhance children’s development, as do investments of parents’ time. Links among endowments, investments, and children’s development appear to differ according to the domain of development (e.g., achievement, behavior, health). Characteristics of the children also affect the level and type of investments that parents make in their offspring (Becker 1991, Foster 2002). For example, if a young child is talkative and enthusiastic about learning, parents are more likely to purchase children’s books or take the child to the library.

Becker’s (1991) household production theory suggests that children from poor families lag behind their economically advantaged counterparts in part because their parents have fewer resources to invest in them. Compared with more affluent parents, poor parents are less able to purchase inputs for their children, including books and educational materials at home, high-quality child care settings and schools, and safe neighborhoods. Economically disadvantaged parents may also have less time to invest in their children owing to higher rates of single parenthood, nonstandard work hours, and less flexible work schedules. This, too, may have negative consequences for children. Evidence suggests that the amount of cognitive stimulation in the home environment varies with changes in family income (Votruba-Drzal 2006).

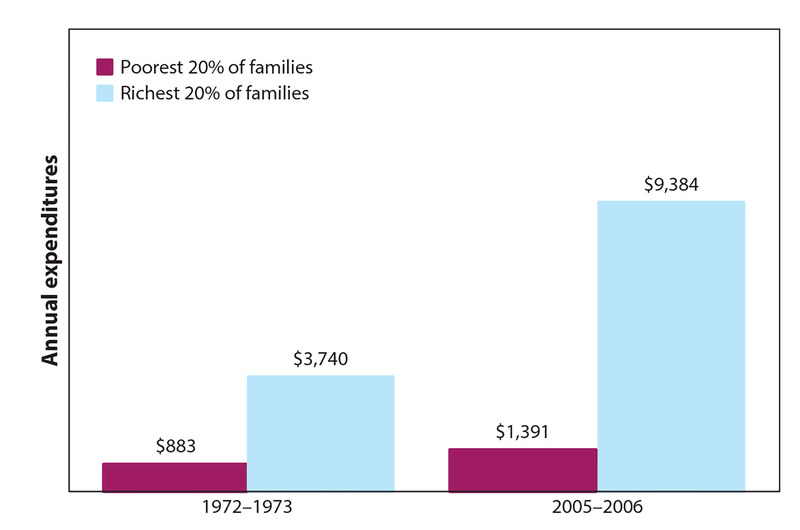

According to data from the Consumer Expenditure Surveys (http://www.bls.gov/cex/), low-income families in 1972–1973 spent approximately $850 (in 2011 dollars) per year per child on child enrichment resources such as books, computers, high-quality child care, summer camps, and private school tuition. Higher-income families spent more than $3,500, already a substantial difference (Figure 2; Duncan & Murnane 2011a). By 2005–2006, low-income families had increased their expenditures to more than $1,300, but high-income families had increased theirs much more, to more than $9,000 per child per year. The differences in spending between the two groups almost tripled in the intervening years. The largest spending differences were for activities such as music lessons, travel, and summer camps (Kaushal et al. 2011). Nonexperimental studies suggest that differences in the quality of the home environments of poorer and more advantaged children account for a substantial portion of the association between poverty and children’s educational achievement. Thus, economists contend that family income matters to children because it enables parents to buy many things that support their children’s learning and healthy development.

Figure 2.

Family enrichment expenditures on children. Calculations are based on data from the Consumer Expenditure Surveys (presented in Duncan & Murnane 2011a,b). Amounts are in 2012 dollars.

The family stress and investment pathways are complemented by insights from cognitive psychology and by behavioral economic studies of cognitive resources and decision making under conditions of scarcity. Enhanced family income may create more enriching and less stressful family environments by reducing the cognitive load that parents face (Gennetian & Shafir 2015). Studies show that conditions of scarcity place demands on limited cognitive resources, directing attention to some problems at the expense of others (Mani et al. 2013). Research, much of which has been conducted in developing countries, has found that making economic decisions under a variety of conditions of scarcity reduces adults’ subsequent behavioral self-control and renders them less able to regulate their own behavior to pursue longer-term goals (Mullainathan & Shafir 2013). The many daily tasks that require poor adults to make complicated decisions and evaluate consequential trade-offs deplete their cognitive resources, increasing the likelihood that subsequent decisions will favor more impulsive and counterproductive choices.

Cultural Perspective

Sociological theories about the ways in which the norms and behavior of poor families and communities affect children were integrated into Oscar Lewis’s (1969) culture of poverty model. Drawing from field work with poor families in Latin America, Lewis argued that the poor were economically marginalized and had no opportunity for upward mobility. Individuals responded to their marginalized position with maladaptive behavior and values. The resulting culture of poverty was characterized by weak impulse control and an inability to delay gratification, as well as feelings of helplessness and inferiority—conditions unlikely to change in response to a social program that might boost family income by several thousand dollars. These adaptations manifested in high levels of female-headed households, sexual promiscuity, crime, and gangs. Although Lewis acknowledged that these behaviors emerged in response to structural factors, he theorized that such values and behaviors were transmitted to future generations, and therefore they became a cause of poverty:

By the time slum children are age six or seven they have usually absorbed the basic values and attitudes of their subculture and are not psychologically geared to take full advantage of changing conditions or increased opportunities. (Lewis 1966, p. xlv)

Cultural explanations for the effects of poverty on children have thus suggested that high levels of nonmarital childbearing, joblessness, female-headed households, criminal activity, and welfare dependency among the poor were likely to be transmitted from parents to children. From the mid-1980s through the 1990s, scholars expanded the scope of this argument by paying closer attention to the origins of cultural and behavioral differences. For example, some researchers emphasized the role of individual choice in the face of the liberal welfare state’s perverse incentives rewarding single-mother households and joblessness among men (e.g., Mead 1986). Others have stressed the importance of structural and economic factors, including the concentration of neighborhood poverty, the social isolation of poor inner-city neighborhoods, and the deindustrialization of urban economies (Massey 1990; Wilson 1987, 1996). They contend that these structural factors negatively affect community norms and influence the behavior of inner-city adults and their children.

A common criticism of culture of poverty explanations is that they fail to differentiate the behavior of individuals from their values and beliefs (Lamont & Small 2008). Evidence suggests that disadvantaged individuals hold many middle-class values and beliefs, but circumstances make it difficult for them to behave accordingly. For example, one study showed that poor Black women value marriage and recognize the benefits of raising children in a two-parent household (Edin & Kefalas 2005). However, their low wages, as well as Black men’s high rates of unemployment and incarceration, lead poor women to conclude that marriage is out of their reach.

Traditional views of the culture of poverty do not account for this disconnect between values and behaviors. Incarnations of the cultural perspective over the past two decades argue that it is important to take culture seriously not because the fundamental values and beliefs of the poor differ from those of the middle classes but because it is important to understand the heterogeneity in the worldviews created by the living conditions that poor individuals experience. More specifically, focusing on how conditions and experiences give rise to limited worldviews facilitates an examination of how poverty may constrain the range of choices and productive pathways available to low-income families (Lamont & Small 2010).

Annette Lareau’s (2003) qualitative study of family management strategies identifies other differences between the cultural child-rearing repertoires of high- and low-income families, including the degree to which middle-class parents manage their children’s lives and working-class and poor parents leave children to play and otherwise organize their activities on their own:

In the middle class, life was hectic. Parents were racing around from one activity to another…. Because there were so many activities, and because they were accorded such importance, child’s activities determined the schedule for the entire family…. [In contrast, in working class and poor families,] parents tend to direct their efforts toward keeping children safe, enforcing discipline, and, when they deem it necessary, regulating their behavior in certain areas…. Thus, whereas middle-class children are often treated as a project to be developed, working class and poor children are given boundaries for their behavior and then allowed to grow. (Lareau 2003, pp. 35, 66–67)

These middle-class child-rearing patterns are called concerted cultivation and involve providing stimulating learning activities and social interactions that parents believe will promote their children’s social and cognitive development. In contrast, the natural growth perspective of working-class and poor parents often stops at providing basic supports (e.g., food, shelter, comfort). Such differences in cultural repertoires provide a distinct advantage to middle-class children and contribute to the intergenerational transmission of social class.

These cultural theories extend the resource and investment perspectives discussed above. Class-related differences in the parenting practices of the families studied by Lareau arise, in part, from income differences that enable some to support a much broader repertoire of activities for their children. However, some of the differences arise from divergent beliefs or worldviews about how children succeed and the best kinds of parenting practices for children. Once these beliefs are adopted, they are unlikely to change in response to policy-relevant changes in family income.

DEVELOPMENTAL PERSPECTIVES: POVERTY ACROSS CHILDHOOD AND ADOLESCENCE

Theoretical perspectives on the effects of family poverty on children have focused on how poverty shapes children’s environments rather than on processes operating within the child. Attention to within-child processes, however, suggests the importance of greater specification of the implicated developmental processes and greater attention to the developmental timing of poverty. For some children, poverty persists throughout childhood; however, for most children, poverty lasts for shorter periods of time. The developmental perspective leads to the hypothesis that for some outcomes, the timing of economic disadvantage during childhood and adolescence may matter for children’s development. The fields of economics and developmental neuroscience have provided conceptual arguments and, to a lesser extent, empirical evidence for the importance of development in the earliest years of children’s lives. The field of developmental neuroscience suggests that both the stress response processes (discussed in the section Family and Environmental Stress) and the more general development of brain circuitry early in life may be important mechanisms driving the effects of poverty and related environments on children.

Economists Cunha & Heckman (2007) posit a cumulative model of the production of human capital that allows for the possibility of differing childhood investment stages, as well as roles for the past effects of cognitive and socioemotional skills on the future development of those skills. In this model, children have endowments from birth of cognitive potential and temperament that reflect a combination of genetic and prenatal environmental influences. The Cunha & Heckman (2007) model highlights the interactive nature of skill building and investments from families, preschools and schools, and other agents. It suggests that human capital accumulation results from self-productivity—skills developed in earlier stages bolstering the development of skills in later stages—as well as the dynamic complementary process that results when skills acquired prior to a given investment increase the productivity of that investment. These two principles are combined in the hypothesis that skill begets skill. This model predicts that economic deprivation in early childhood creates disparities in school readiness and early academic success that widen over the course of childhood.

Developmental neuroscience has contributed to the understanding of the developmental timing of poverty by arguing that early environments, especially adverse environments, play an especially important role in shaping early brain development (Rosenzweig 2003). Some studies have focused on family socioeconomic status generally or on income specifically as an important dimension of early contexts (Brito & Noble 2014, Hackman & Farah 2009, Noble et al. 2015a). In contrast to the social science literature, these studies focus on specific cognitive skills and, increasingly, on direct measures of brain function and structure. This innovation is critical because differences in neural circuitry are often evident at an early age, well before general cognitive or behavioral differences can be detected (Fox et al. 2010), and can thus serve as an early indicator of the development of cognitive disparities. Moreover, neuroscience provides an explanatory framework for the physiological mechanisms early in life that lead to lower cognitive skills and other observed behavioral differences later in life. Distinct brain circuits support discrete cognitive skills, and differentiating between these underlying neural systems may point to different causal pathways and avenues for intervention. Specifically, one of the key pathways linking early childhood SES to adult outcomes encompasses the developmental assembly and long-term functioning of particular brain circuits, namely, circuits that are important for cognitive and emotional control functions and self-regulatory behaviors that impact a range of adult processes.

Neuroscience studies have documented SES-based differences in language use, memory, executive function, and socioemotional processing. Socioeconomic disparities in neurocognitive skills have been reported beginning in toddlerhood and continuing throughout adolescence. Electro-physiological and brain imaging research offers evidence that, for children, family socioeconomic disadvantage predicts indicators of brain function hypothesized to reflect the delayed development of the prefrontal cortex. In turn, delayed development of the prefrontal cortex can affect neurocognitive abilities, such as selective attention, reading and language acquisition, decision making, and higher-order cognition. SES-based differences have also been found in the volume, structure, and function of brain regions that support these skills in studies of older children and adolescents using magnetic resonance imaging techniques (Hanson et al. 2013; Kim et al. 2013; Noble et al. 2012a,b, 2015a,b). Noble et al. (2015a,b) reported associations between family income and the size of the brain’s surface beginning at age three, particularly in regions supporting children’s language and executive functioning; this association was strongest among the most disadvantaged families.

Neuroscience studies suggest that the early experience of poverty may shape children’s brain development and that such mechanisms may underlie observed differences in subsequent cognitive skills, behavior, school completion, and achievement. However, despite the specificity and rigor of brain measurement, these descriptive studies of small samples support neither causal inference nor population generalizability. The data and methods typically rely on comparing low-income children with their higher-income counterparts and, at best, control for only a small handful of other characteristics. Thus, it is hard to know whether income is a causal agent in producing the differences in brain structure or function or whether income is just confounded with other conditions that matter.

Additional support for the idea that poverty in early childhood may be particularly pernicious for children’s development comes from intensive programs aimed at providing early care and educational experiences for high-risk infants and toddlers. The best known are the Abecedarian program, a full-day, center-based, educational program for children who are at high risk for school failure, starting in early infancy and continuing until school entry; and the Perry Preschool program, which provided one or two years of intensive center-based education for preschoolers (Duncan & Magnuson 2013). Both of these programs have generated long-term improvements in subsequent education, criminal behavior, and employment—outcomes that are strongly associated with poverty, although the general pattern of effects from other early childhood education programs is more modest.

Although income in early childhood may matter the most for early brain development, several studies suggest that economic circumstances experienced later in childhood and adolescence may also be important (Akee et al. 2010, Maynard & Murnane 1979). For example, economic and sociological studies demonstrate that income increases may also be beneficial for low-income adolescents and young adults, particularly when used to help pay for postsecondary schooling. Although Pell Grants and other sources of financial aid drive down the net costs of college for low-income students, the costs of enrollment in public four-year colleges have increased faster than grants have. In contrast, the costs of attendance at a public community college have not increased over the past two decades for students from low-income families because the amount of aid has expanded to cover the higher price. Of course, many low-income students and their parents either lack awareness of the aid that is available or are discouraged by the extremely complex federal financial aid application form (Bettinger et al. 2012).

Additional evidence highlighting the potential importance of family economic circumstances in middle childhood and adolescence comes from studies in social and health psychology suggesting that poverty, and economic inequality more generally, may affect children by creating social distance that imposes harmful intrapsychic costs (Boyce et al. 2012, Odgers et al. 2015). Heberle & Carter (2015) argue that poor individuals may experience status anxiety related to their membership in a low-status group within a highly stratified and unequal society. Thus, the psychological costs of poverty may be exacerbated when the economic and social distance between low-income and higher-income peers is greater. Heberle & Carter (2015) further suggest that the developmental task of forming a sense of self in relation to others may make poor children’s anxiety derived from social status especially harmful during middle childhood and adolescence. Similarly, Odgers (2015) argues that low-income children attending schools with affluent peers may be doubly disadvantaged because they are directly affected by both their families’ poverty and upward social comparisons that will negatively shape their internal attributions, behavior, and health. Odgers et al. (2015) argue that low-income children who are not exposed to as many affluent peers will not experience the harmful effects of upward comparison. Thus, one important factor in understanding whether poverty has adverse effects on aspects of children’s development is the salience of their poverty as determined by their social distance from affluent peers.

However, the empirical support for this proposition remains limited. Odgers et al. (2015) finds that low-income boys have higher levels of antisocial behavior in neighborhoods in England that are of mixed economic status compared with boys who are in more economically segregated neighborhoods. This pattern does not hold true for girls, and more generally, it is not clear to what extent this pattern is generalizable across contexts. For example, descriptive portraits of children’s achievement and behavior at school entry do not find that poor children residing in neighborhoods with low rates of poverty have worse behavior or lower achievement than poor children residing in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty (S. Wolf, K. Magnuson, and R. Kimbro, unpublished manuscript). Of course, it is possible that the harm from upward social comparison is more prominent in particular contexts or for children during particular developmental periods. More work is necessary to better understand whether and under what conditions these risks of upward social comparison may occur and to consider whether these risks are offset by access to the improved economic, institutional, and social resources often afforded to low-income children by greater economic integration (Reardon & Owens 2014).

Finally, economic conditions in middle childhood and adolescence may be important if stereotype threat comes into play. Stereotype threat refers to the risk of conforming to negative stereotypes about the group with which an individual identifies. In the case of identification by social class, the argument is that when the contexts experienced by children make social class highly salient, low-income children are more likely to conform to the stereotype of poor children as demonstrating lower achievement (Croizet & Claire 1998). The empirical evidence related to status anxiety and stereotype is suggestive but not extensive enough to draw clear conclusions. Moreover, the work to date describes relevant intraindividual processes but does not articulate how these processes interface with developmental processes. For example, are the harmful effects of upward social comparison most detrimental when children are developing their beliefs about self-efficacy in early middle childhood or during adolescence, when their understanding of how others view poor individuals becomes more complete and possibly negative?

Both theory and correlational evidence suggest that the effects of economic deprivation on children may depend on when in childhood or adolescence that deprivation is experienced. Numerous neuroscience studies have found that brain structure and function vary by income level early in childhood, suggesting that early deprivation might be especially important, a result confirmed in some life-cycle correlational studies. Both social psychological literature and the increase in outof-pocket costs for college suggest that adolescence may also be a period in which development is sensitive to income fluctuations.

ASSESSING CAUSAL CONSEQUENCES OF POVERTY: METHODS AND RESULTS

Studying how poverty affects children and families is challenging. The most important construct of interest, poverty, is expensive to manipulate, leaving the researcher little choice but to use observational data to disentangle whether and how poverty influences the developmental processes and outcomes of children. However, because poor and nonpoor children differ in so many ways, it is hard to argue that the differences between low-income children and their more affluent peers are due only to income.

Studies aimed at estimating the influence of income on child development differ in their methodological rigor. At one end are correlational studies that analyze associations between family income and child outcomes, with few adjustments for confounding factors. These studies are common, particularly in neuroscience, but are likely to be plagued by biases that lead to overestimates of the causal impacts of income. At the other end are large social policy experiments in which families are randomly assigned to receive additional income. If implemented correctly, experiments provide unbiased estimates of income effects. However, experimental studies are exceedingly rare and sometimes condition their income support on behavior such as full-time work, which may exert its own influence on child development. Quasi-experiments, in which income changes are beyond the control of families, are almost as reliable as experiments. The Evans & Garthwaite (2014) EITC expansion study is an example of quasi-experimental research based on policy changes that increase the generosity of programs like the EITC. In this case, the larger increase in payments for two or more as opposed to one child created income variation that was beyond the control of recipient families.

School Achievement and Attainment

The differences in academic skills and attainment between poor and nonpoor children have been well documented and described. The focus on these outcomes reflects both the somewhat greater ease of measuring them, using test scores of academic performance and completed schooling, and their importance in social science theories about intergenerational social mobility and status attainment. However, the large body of longitudinal and observational studies varies considerably in the extent to which they address threats to causal inference. In a review, Haveman & Wolfe (1995) conclude that, in studies conducted prior to 1995, growing up in poverty is consistently related to lower education-related outcomes. However, they also point out that these studies suffered from numerous shortcomings, including the lack of a common framework to guide the choice of model specification, and as a result the inclusion of variables often appears to be ad hoc.

The strongest experimental evidence in the literature relates income increases to children’s school achievement and attainment. The only large-scale randomized interventions to alter family income directly were the US Negative Income Tax Experiments, which were conducted between 1968 and 1982 to identify the influence of guaranteed income on parents’ labor force participation. Three of the sites (Gary, Indiana, and rural areas in North Carolina and Iowa) measured impacts on achievement gains for children in elementary school; significant impacts were found in two of the three sites (Maynard 1977, Maynard & Murnane 1979). In contrast, no achievement differences were found for adolescents and young adults. Impacts on school enrollment and attainment for youth were more uniformly positive, with both the Gary site and a fourth site in New Jersey reporting increases in school enrollment, high school graduation rates, or years of completed schooling. Teachers rated student comportment through eighth grade in the rural sites in North Carolina and Iowa; results showed improvements in North Carolina but not in Iowa. Taken together, this pattern of findings suggests that income may be more important for the school achievement of preadolescents than that of adolescents. In contrast, income may matter more for the completed schooling of adolescents and young adults. However, the small sample sizes and high rates of missing school achievement data make it difficult to draw firm conclusions from this work, in which an understanding of the effects of income supplements on children was not one of the primary goals of the research.

A second body of evidence on the importance of family income comes from experimental welfare reform evaluation studies undertaken during the 1990s to incentivize parental employment by providing wage supplements to working-poor parents. Moreover, some of these studies measured the test scores of at least some children who had not yet entered school when the programs began. One study analyzed data from seven random-assignment welfare and antipoverty policies, all of which increased parental employment; only some of these policies increased family income (Morris et al. 2005). The combined impacts of higher income and more maternal work on children’s school achievement varied markedly by the children’s age. Treatment-group children who were between the ages of four and seven when the programs took effect, many of whom made the transition into elementary school after the programs began, scored significantly higher on achievement tests than their control-group counterparts. A sophisticated statistical analysis of the data on these younger children suggests that a $3,500 annual income boost is associated with a gain in achievement scores of about one fifth of a standard deviation (Duncan et al. 2011).

In contrast to the positive findings for younger children, the achievement of older children (ages 8 to 11) did not appear to benefit from the income and employment programs, and the achievement of children who were 12 and 13 seemed to be hurt by the programs’ efforts to increase family income and parental employment. These results may be explained by maternal employment forcing teens to take on child care responsibilities that interfered with their school work (Gennetian et al. 2002).

Two quasi-experimental studies have focused on expansions in tax credits and a third on casino disbursements as sources of positive income shocks. Studies of expansions to the EITC in the mid-1990s (Dahl & Lochner 2012) and National Child Benefit program across Canadian provinces (Milligan & Stabile 2011) found evidence that increased tax income coincided with modestly higher achievement scores during middle childhood among low-income families. A third quasi-experimental study examined the impact of the opening of a casino by a Native American tribal government in North Carolina, which distributed approximately $6,000 annually to each adult member of the tribe (Akee et al. 2010). A comparison of Native American youth with non-Native American youth, before and after the casino opened, found that receipt of casino payments for approximately six years increased the school attendance and high school graduation rates of poor Native American youth. Achievement test scores were not available in these data, nor were data available on children under the age of nine.

Related evidence on income effects comes from evaluations of programs providing conditional cash transfer (CCT) payments to low-income families. First tested in developing countries as a way to incentivize children’s continued schooling and medical care, CCTs distribute cash to mothers only when they engage in targeted behavior such as well-baby visits or their children meet school attendance goals (Fiszbein et al. 2009). Many of the programs tested in developing countries produced significant improvements in children’s development, education, and health. It is unclear whether the improvements are caused by the increased income or the structure of CCTs, which provide incentive payments that directly offset the specific and large opportunity cost of the desired behavior.

In the United States, the evaluation of Opportunity New York City, a CCT program aimed at reducing family poverty and economic hardship, showed no impacts on children’s school test scores after two years of participation (Riccio et al. 2010, 2013). Possible explanations for the null effects include the complexity of the payment schedule, the diversity and complexity of behaviors targeted by the intervention, implementation difficulties, the small amount of cash support relative to the high cost of living in New York, and the fact that the children were older than those enrolled in many other income studies.

Two lessons emerge from these experimental and quasi-experimental studies. First, achievement gains are selective and depend on the children’s age when income gains were received. Elementary school students and children making the transition into school generally demonstrated the most consistent achievement increases. For adolescents, the achievement changes were mixed, with different studies finding positive, null, and even negative impacts for achievement outcomes. Second, in the case of adolescents and young adults, income appears to affect educational attainments, such as high school graduation, and completed years of schooling rather than test scores. Given the high costs of postsecondary education, the effect of family income on completed schooling is not surprising.

Behavior and Mental Health

In addition to lagging behind their economically advantaged peers when it comes to academic achievement and educational attainment, low-income children are typically rated by their parents and teachers as having more behavior problems than more affluent children. This is reflected in elevated levels of externalizing problems, such as aggression and acting out, and internalizing problems, such as depression and anxiety. In adolescence, poverty is related to higher rates of nonmarital fertility and criminal activity. For example, compared with children whose families had incomes of at least twice the poverty line during their early childhood, poor males are more than twice as likely to be arrested. For females, poverty is associated with a more than fivefold increase in the likelihood of bearing a child out of wedlock prior to age 21 (Duncan et al. 2010; Table 1). Again, the extent to which these correlations reflect causal impacts remains uncertain.

As is the case for studies of achievement, most poverty-related studies of behavior have been correlational in nature and have varied in the extent to which they have addressed the challenges of identifying causal effects. Using longitudinal data from nationally representative and diverse samples, links have been found between low income and several dimensions of psychological functioning, including internalizing and externalizing behaviors, antisocial behavior, inadequate self-regulation, and poor mental health (Blau 1999, Mistry et al. 2002, Votruba-Drzal 2006). For example, 7.8% of poor parents versus 4.6% of nonpoor parents rated their children as having difficulties with emotions, concentration, behavior, or getting along with others (Simpson et al. 2005). However, these associations are not consistently replicated in studies that hold constant related disadvantages, such as family structure and parental education (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn 1997, Duncan et al. 2010, Mayer 1997). For example, Dearing et al. (2006) examined within-child associations between family income and behavior of young children and found significant negative effects of lower family income on externalizing behavior, especially for children who live in chronically poor households, but not on internalizing behavior.

Few studies have employed rigorous experimental or quasi-experimental designs to study children’s psychological and behavioral health. An important exception is the above-cited study by Akee and colleagues (2010) that compared Native American children with non-Native American children before and after a casino opened on tribal land. They found that receipt of casino payments reduced criminal behavior, drug use, and behavioral disorders including depression, anxiety, and other emotional disorders such as conduct or oppositional disorders. This study of adolescents provides a compelling research design and suggests that income may play a causal role in at least some aspects of adolescent mental health.

Associations between income and dimensions of children’s behavioral functioning tend to be less consistent and less robust in studies that employ more rigorous methodological approaches and analytical techniques (Reiss 2013). However, the most compelling quasi-experimental study to date shows that income is strongly linked to improvements in behavioral disorders. This suggests that, to the extent that there are causal connections between income and behavior in childhood, these connections may be selective, with some evidence suggesting that there are stronger associations between income and externalizing, rather than internalizing, problems.

However, it is important to note that few studies have been able to differentiate between these subtypes of problem behavior or look carefully at the timing of poverty across childhood. The global measures of child behavior problems that are commonly found in large nationally representative data tend to rely more heavily on items that assess externalizing problems, such as aggression and oppositional behavior, rather than those assessing internalizing problems, including depression and anxiety. Additionally, research in the field of developmental psychopathology has shown that internalizing and externalizing disorders follow different developmental courses as children age (Lewis & Rudolph 2014). Externalizing problems tend to peak during early childhood and then subside as children age, with a second period of elevation for some children in adolescence. Prevalence of problem internalizing behaviors tends to be low throughout early and middle childhood, with increases occurring during the transition into adolescence. Yet most studies examine children only in one age range or, more commonly, collapse the data across developmental stages (e.g., Blau 1999, D’Onofrio et al. 2009). This may obscure important associations, and research would benefit from increased attention to these differences in developmental trajectories, as well as to unique associations between poverty and particular dimensions of children’s behavioral functioning.

Childhood Poverty and Development into Adulthood

Studies examining the long-term effects of childhood poverty have begun to appear in the past decade. Some have examined associations between poverty (e.g., family income in early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence) and achievement and behavioral functioning into adulthood. Like other observational studies, these analyses face challenges in identifying causal effects, but their findings establish that early childhood income predicts adult outcomes. For example, Duncan et al. (2010) and Ziol-Guest et al. (2012) use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) on individuals born in the early years of the study, for whom adult outcomes were collected when they were in their 30s. The PSID measures income in every year of a child’s life from the prenatal period through age 15, making it possible to measure poverty experiences and family income early in life (from the prenatal period through the fifth year of life in one study and through the first year in the other) as well as later in childhood and in adolescence. Analysis of these data indicates that for families with average early childhood incomes below $25,000, an annual boost to family income during early childhood (from birth to age five) is associated with increased adult work hours and a rise in earnings, as well as with reductions in receipt of food stamps (but not receipt of Aid to Families with Dependent Children and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits for female children). Family income in other childhood stages was never significantly related to adult earnings and work hours.

As discussed in the section Cultural Perspective, children raised in low-income households also have higher rates of arrest and incarceration in adulthood than their affluent counterparts (Bjerk 2007, Duncan et al. 2010). Duncan and colleagues (2010 ) found that boys living in poverty during the first five years of life were more than twice as likely to be arrested as boys who had family incomes over twice the poverty threshold (28% versus 13%). However, taking into account the variety of ways in which poor families differ from wealthier families reduced the associations to statistical insignificance. Thus, it is questionable whether elevations in criminal activity can be attributed to poverty per se rather than to the range of social disadvantages associated with poverty.

When it comes to socioeconomic variability in important adult behaviors, such as arrests, nonmarital childbearing, and educational attainment, the timing of income seems to be important, with income in adolescence more strongly related to adult behavior than is income in earlier life stages. Importantly, few studies have assessed these linkages, so additional research is necessary to confirm these findings; the use of compelling quasi-experimental research designs is especially important.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH

A vitally important question in this research field is to what extent variability in household income actually causes differences in children’s development. There are many early intervention or enrichment programs designed to promote child development, and most of the program evaluations employ random assignment of subjects to treatment and control groups. Why not adopt the same strategy to assess the causal impact of the components of SES? We should not resign ourselves to the conclusion that SES cannot be manipulated because policies can change individual components of SES, in particular income.

Our review has described several instances of developmental studies taking advantage of ongoing random assignment policy evaluations in which boosting family income is an important component of the experimental manipulation. Several found that both test-based and teacher reports of achievement were affected by these policies. Health and behavioral outcomes were less frequently examined (and often less well measured).

Ongoing data collections involving the measurement of child and adolescent outcomes might be able to take advantage of quasi-experimental manipulation of income. As reviewed in the section Assessing Causal Consequences of Poverty: Methods and Results, several studies have taken advantage of ongoing data collection efforts measuring children’s achievement to assess the impacts of changes in the generosity of income support policies such as the US EITC and the Canadian National Child Benefit. Other natural experiments are possible, as indicated by the studies by Akee and colleagues (2010, 2015) that linked data on child outcomes from the Great Smokey Mountain Study of Youth to the timing of the introduction of a casino by a tribal government in North Carolina.

International scholarship estimating causal effects has surpassed efforts by US scholars. Researchers have implemented field studies of CCTs and unconditional cash transfers in many developing countries (Fiszbein et al. 2009). The main outcomes of interest in these studies are often economic and material conditions, which are not traditionally of interest in psychological studies; however, attention is increasingly being paid to the use of these experiments to understand how poverty and conditions of economic standing affect individuals and families. To significantly advance our understanding of how developmental processes are affected by economic conditions, we must be willing to undertake more ambitious studies rather than to rely on methods and samples of convenience.

An alternative, if somewhat expensive, strategy would be to launch an experimental developmental study devoted to assessing the impact of the manipulation of income. Suppose low-income families with newborns were recruited into a five-year study of early child development and randomly assigned to treatment or control groups. The study provides control families nominal monthly payments (say $20) and experimental families much larger monthly payments of a scale associated with policies such as the EITC (say $333 per month, or $4,000 per year). The $3,760 annual difference between the treatment and control groups constitutes a substantial income increase for a family with an income near the poverty line. Quasi-experimental studies suggest that this income increase might be sufficient to boost test scores by approximately 0.20–0.25 of a standard deviation, and a simple power calculation shows that approximately 1,000 cases would be sufficient to provide 80% power to detect an effect of this size (given expected attrition) on outcomes. Rigorous laboratory measures of children’s cognitive and brain development, as well as measures of health, stress, and behavior, could be gathered at approximately age three. Careful thought would need to be given to whether more sophisticated measures of brain functioning might be expected to change by at least 0.20 SD. This approach would also help one to better understand how poverty reduction improves brain functioning; one could measure elements of family context expected to link poverty to child development, including parent stress, family expenditures, routines and time use, parenting practices, and child care arrangements.

A large-scale poverty reduction study would not be without challenges and complications, but the potential reward of understanding how and to what extent poverty affects developmental processes would be invaluable to the field. This reorientation of the field, with the resulting goal of studying experimentally or quasi-experimentally induced variation in poverty and economic resources, would vastly increase both the specificity and the certainty of our knowledge about how income affects neurocognitive development (Duncan & Magnuson 2012). This approach would resolve lingering questions about the importance of income in the constellation of potential causal factors leading to disadvantage. Perhaps even more importantly, it would also advance policy discussion by providing a way to better assess the consequences of decisions that might increase or decrease the incomes of parents with young children.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Portions of this article were adapted from a more general review of socioeconomic status that the authors wrote for the Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science (Duncan et al. 2015) and from Duncan et al. (2014).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

G.D. and K.M. have a proposal under review for a randomized controlled trial to test the impact of income supplements on the cognitive development of young children.

LITERATURE CITED

- Akee RKQ, Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. 2010. Parents’ incomes and children’s outcomes: a quasi-experiment using transfer payments from casino profits. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ 2(1):86–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akee R, Simeonova E, Costello EJ, Copeland W. 2015. How does household income affect child personality traits and behaviours? Work. Pap. No. 21562, Natl. Bur. Econ. Res [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. 1991. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Bettinger EP, Long BT, Oreopoulos P, Sanbonmatsu L. 2012. The role of application assistance and information in college decisions: results from the H&R Block FAFSA experiment. Q. J. Econ 127(3):1205–42 [Google Scholar]

- Bjerk D 2007. Measuring the relationship between youth criminal participation and household economic resources. J. Quant. Criminol 23(1):23–39 [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Granger DA, Willoughby M, Mills-Koonce R, Cox M, et al. 2011. Salivary cortisol mediates effects of poverty and parenting on executive functions in early childhood. Child Dev 82(6):1970–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau DM. 1999. The effect of income on child development. Rev. Econ. Stat 81(2):261–76 [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Obradović J, Bush NR, Stamperdahl J, Kim YS, Adler N. 2012. Social stratification, classroom climate, and the behavioral adaptation of kindergarten children. PNAS 109(Suppl. 2):17168–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito NH, Noble KG. 2014. Socioeconomic status and structural brain development. Front. Neurosci 8:276. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL. 1997. Maternal psychological functioning, family processes, and child adjustment in rural, single-parent, African American families. Dev. Psychol 33(6):1000–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Flor D, McCrary C, Hastings L, Conyers O. 1994. Financial resources, parent psychological functioning, parent co-caregiving, and early adolescent competence in rural two-parent African-American families. Child Dev. 65(2):590–605 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LP, Millet DB, Marshall JD. 2014. National patterns in environmental injustice and inequality: outdoor NO2 air pollution in the United States. PLOS ONE 9(4):1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Elder GH Jr. 1994. Families in Troubled Times: Adapting to Change in Rural America. New York: A. de Gruyter [Google Scholar]

- Cook TD. 2014. Generalizing causal knowledge in the policy sciences: external validity as a task of both multiattribute representation and multiattribute extrapolation. J. Policy Anal. Manag 33(2):527–36 [Google Scholar]

- Croizet JC, Claire T. 1998. Extending the concept of stereotype threat to social class: the intellectual under-performance of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull 24(6):588–94 [Google Scholar]

- Cunha F, Heckman J. 2007. The technology of skill formation. Am. Econ. Rev 97(2):31–47 [Google Scholar]

- Dahl GB, Lochner L. 2012. The impact of family income on child achievement: evidence from the earned income tax credit. Am. Econ. Rev 102(5):1927–56 [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, McCartney K, Taylor BA. 2006. Within-child associations between family income and externalizing and internalizing problems. Dev. Psychol 42(2):237–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. 2015. Income and poverty in the United States: 2014 Curr. Popul. Rep P60–252, US Census Bur, Washington, DC: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/ publications/2015/demo/p60-252.pdf [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Goodnight JA, Van Hulle CA, Rodgers JL, Rathouz PJ, et al. 2009. A quasi-experimental analysis of the association between family income and offspring conduct problems. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol 37(3):415–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, eds. 1997. Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson K. 2012. Socioeconomic status and cognitive functioning: moving from correlation to causation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci 3(3):377–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson K. 2013. Investing in preschool programs. J. Econ. Perspect 27(2):109–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Magnuson K, Votruba-Drzal E. 2014. Boosting family income to promote child development. Future Child. 24(1):99–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G, Magnuson K, Votruba-Drzal E. 2015. Children and socioeconomic status In Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science, Vol. 4: Ecological Settings and Processes in Developmental Systems, ed. Bornstein MH Leventhal T, pp. 534–73. New York: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Morris PA, Rodrigues C. 2011. Does money really matter? Estimating impacts of family income on young children’s achievement with data from random-assignment experiments. Dev. Psychol 47(5):1263–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Murnane RJ. 2011a. Introduction: the American dream, then and now. See Duncan & Murnane 2011b, pp. 3–23 [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Murnane RJ, eds. 2011b. Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances. New York/Chicago: Russell Sage Found./Spencer Found. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Ziol-Guest KM, Kalil A. 2010. Early-childhood poverty and adult attainment, behavior, and health. Child Dev. 81(1):306–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Kefalas M. 2005. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage. Berkeley, CA: Univ. California Press [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. 1974. Children of the Great Depression. Chicago, IL: Univ. Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr., Nguyen TV, Caspi A 1985. Linking family hardship to children’s lives. Child Dev. 56(2):361–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. 2011. Differential susceptibility to the environment: an evolutionary-neurodevelopmental theory. Dev. Psychopathol. 23(1):7–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW. 2004. The environment of childhood poverty. Am. Psychol 59(2):77–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WN, Garthwaite CL. 2014. Giving mom a break: the impact of higher EITC payments on maternal health. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 6(2):258–90 [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Saltzman H, Cooperman JL. 2001. Housing quality and children’s socioemotional health. Environ. Behav 33(3):389–99 [Google Scholar]

- Fiszbein A, Schady NR, Ferreira FH. 2009. Conditional cash transfers: reducing present and future poverty World Bank Policy Res. Rep, World Bank, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Foster EM. 2002. How economists think about family resources and child development. Child Dev. 73(6):1904–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SE, Levitt P, Nelson CA. 2010. How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain architecture. Child Dev. 81(1):28–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian LA, Duncan GJ, Knox VW, Vargas WG, Clark-Kauffman E, London AS. 2002. How welfare and work policies for parents affect adolescents: a synthesis of research MDRC Rep., New York, NY: mdrc.org/sites/default/files/full_394.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gennetian LA, Shafir E. 2015. The persistence of poverty in the context of financial instability: a behavioral perspective. J. Policy Anal. Manag 34(4):904–36 [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Landrigan PJ. 2006. Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet 368(9553):2167–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman D, Farah MJ. 2009. Socioeconomic status and the developing brain. Trends Cogn. Sci 13:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson JL, Hair N, Shen DG, Shi F, Gilmore JH, et al. 2013. Family poverty affects the rate of human infant brain growth. PLOS ONE 8(12):e80954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haveman R, Wolfe B. 1995. The determinants of children’s attainments: findings and review of methods. J. Econ. Lit 33(4):1829–78 [Google Scholar]

- Heberle AE, Carter AS. 2015. Cognitive aspects of young children’s experience of economic disadvantage. Psychol. Bull 141(4):723–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal N, Magnuson K, Waldfogel J. 2011. How is family income related to investments in children’s learning? See Duncan & Murnane 2011b, pp. 187–206 [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Cleary PD. 1980. Social class and psychological distress. Am. Sociol. Rev 45(3):463–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim P, Evans GW, Angstadt M, Ho SS, Sripada CS, et al. 2013. Effects of childhood poverty and chronic stress on emotion regulatory brain function in adulthood. PNAS 110(46):18442–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont M, Small ML. 2008. How culture matters for poverty: enriching our understanding of poverty In The Colors of Poverty: Why Racial and Ethnic Disparities Persist, ed. Lin AC, Harris DR, pp. 76–102. New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont M, Small ML. 2010. Cultural diversity and anti-poverty policy. Int. Soc. Sci. J 61(199):169–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A 2003. Unequal Childhoods: Race, Class, and Family Life. Berkeley: Univ. Calif. Press [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Rudolph K. 2014. Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology. New York: Springer [Google Scholar]

- Lewis O 1966. La Vida: A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of Poverty—San Juan and New York. New York: Random House [Google Scholar]

- Lewis O 1969. The culture of poverty In On Understanding Poverty: Perspectives from the Social Sciences, ed. Moynihan DP, pp. 187–200. New York: Basic Books [Google Scholar]

- Loken KV, Mogstad M, Wiswall M. 2012. What linear estimators miss: the effects of family income on child outcomes. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ 4(2):1–35 [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, King S, Meaney MJ, McEwen BS. 2001. Can poverty get under your skin? Basal cortisol levels and cognitive function in children from low and high socioeconomic status. Dev. Psychol 13(3):653–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie JL. 1974. The Cement of the Universe: A Study of Causation. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press [Google Scholar]

- Mani A, Mullainathan S, Shafir E, Zhao J. 2013. Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science 341(6149):976–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. 1990. American apartheid: segregation and the making of the underclass. Am. J. Sociol 96:329–57 [Google Scholar]

- Mayer SE. 1997. What Money Can’t Buy: Family Income and Children’s Life Chances. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press [Google Scholar]