Abstract

Purpose

Over 1.5 million women per year have a benign breast biopsy resulting in concern regarding their future breast cancer (BC) risk. We examine the performance of two BC risk models that integrate clinical and histologic findings in this population.

Methods

Five and 10-year BC risk were estimated by the BC Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) and Benign Breast Disease to BC (BBD-BC) models for women diagnosed with BBD at Mayo Clinic from 1997–2001. Women with BBD were eligible for the BBD-BC, but BCSC also required a screening mammogram. Calibration and discrimination were assessed.

Results

The 2,142 women with BBD, median 50 years, had 56 BC diagnosed within 5 years (118 within 10 years). BBD-BC had slightly better calibration at five (0.89 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.21)) vs. ten years (0.81 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.00)), but similar discrimination at both time periods: (0.68 (95% and 0.66 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.71)), respectively. In contrast, among the 1089 women with screening mammograms (98 BC within 10 years), BCSC had better calibration (0.94; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.43) and discrimination (0.63; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.71) at ten vs. five years (calibration 1.31, 95% CI 0.94 to 2.25; discrimination 0.59, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.71), where discrimination was not different from chance.

Conclusion

The BCSC and BBD-BC models validated in the Mayo BBD cohort, although performance differed by five vs. ten-year risk. Further enhancement of these models is needed to provide accurate BC risk estimates for women with BBD.

Keywords: Benign Breast Disease, Risk Models, Breast Cancer, Absolute Risk, Biopsy

Introduction

As part of early detection efforts for breast cancer (BC), over 1.6 million breast biopsies are performed on women every year within the United States.1 Many women with a confirmed benign biopsy or benign breast disease (BBD) have been shown to be at increased risk of future BC, ranging from population risk for those diagnosed with non-proliferative lesions (NP) to above average risk for those with proliferative lesions without atypia (PDWA), to 4-fold increased risk for those with atypical hyperplasia (AH).2 Being able to provide accurate risk estimates in this population is important.2

The most widely used BC risk prediction tool is the Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (BCRAT), which identifies groups of women at increased risk, but has limited accuracy in predicting risk for individual women3–5 and has been shown to be ineffective at predicting risk in women with AH.6 The only pathologic risk factor included in the BCRAT is presence of AH. The recently developed Benign Breast Disease—to—Breast Cancer (BBD-BC) model, developed in the Mayo BBD cohort2, uses clinical risk factors and pathologic features from the benign biopsy including age-related lobular involution, to predict future risk of either invasive BC or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) following BBD, and has demonstrated greater accuracy than the BCRAT in this setting.7 The Breast Cancer Surveillance and Consortium (BCSC) risk prediction model was developed to estimate risk of incident invasive BC in average risk screened populations by incorporating breast density using Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) criteria along with other epidemiologic risk factors. The BCSC model was also shown to be more accurate than BCRAT.8 Recently, the BCSC was updated to include prior diagnoses of BBD.9

The BCSC model was previously validated in a mammography screening cohort, the Mayo Mammography Health Study,10 but it has not been evaluated in a cohort composed exclusively of women with BBD. The BBD-BC model has not been examined outside of the model development and validation studies.7 This study assesses the performance of both models in an independent sample from Mayo Clinic’s BBD cohort.

Methods

Study Sample

The Mayo Clinic BBD cohort has been described previously, and currently includes 13,528 women ages 18–85 years who underwent a benign breast biopsy between 1967 and 2001 at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN.2,11 Clinical risk factors, demographics and follow-up for BC were identified from questionnaires and medical records, including family history of BC, age of first live birth (AFLB), and number of children.

Each woman was retrospectively followed forward in time from date of biopsy to the first occurrence of BC diagnosis (invasive or DCIS), prophylactic mastectomy, death, or date of last contact, determined using electronic or manual abstraction of medical records, billing data, and mailed questionnaires as described previously.2 Women with less than 6 months of follow-up were excluded.

Women from the BBD cohort with an initial benign biopsy between 1997 and 2001 form the study group used in the current analysis.7 Because the original BBD-BC model was developed in women diagnosed from 1967–1991, this more recent group is mutually exclusive from prior modeling activities and thus is suitable as an independent validation for both the BBD-BD and BCSC models.7 Also, because the BCSC model incorporates BI-RADS density, which was not used clinically at Mayo until 1997, we exclude women with initial biopsies between 1992 and 1996.

Eligibility criteria differed between the two models. First, the BCSC included women with lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and categorized them as having benign disease, whereas BBD-BC excluded women with LCIS at initial biopsy and censored women at time of LCIS diagnosis at subsequent biopsy. Second, the BCSC model only included women who underwent mammography and had corresponding BI-RADS density measures, whereas BBD-BC included women not undergoing mammography or with missing density values. Third, the BCSC model is restricted to women aged 35–74, whereas BBD-BC included women aged 18–85. Finally, the BCSC model only predicts women with invasive cancer as events, whereas the BBD-BC includes a diagnosis of DCIS in its case definition. In order to fairly evaluate and validate the two respective models, we attempted to replicate the study designs of each; thus, final sample sizes and variable definitions for the validation sets differed according to the study-specific criteria described above. For purposes of this study, women in the Mayo BBD cohort with a screening mammogram 24 months prior to biopsy were considered eligible for the BCSC model.

Risk models

Risk variables for the BCSC model include age, pathologic diagnosis (NP, PDWA, AH and LCIS), BI-RADS breast density (see below)12, race (White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaskan Native, Hispanic, other, mixed or unknown) and number of first degree relatives with BC (none, one or more, unknown). The BBD-BC model includes age, pathologic diagnosis (NP, PDWA, AH), number of foci of AH (none, 1, 2, 3 or more), lobular involution (none, partial, complete), radial scars (absent, present), combined variable of sclerosing adenosis (SA) or columnar cell alteration (CCA) (present/absent), AFLB and number of children combined (<21 and one or more children, ≥21 and 3 or more children, ≥21 and 1–2 children, nulliparous), and family history of BC (none or any family history in first through third degree relative).

Histologic Examination

Pathologic variables were assessed by an experienced study pathologist (DWV) during histologic review of archived hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) slides from BBD diagnosis. Benign breast lesions were categorized using the criteria of Dupont and Page into NP, PDWA, or AH13–15.

If there were multiple diagnoses on a single biopsy or multiple biopsies were performed, the most severe diagnosis was assigned. Individual histologic components were also determined, including SA, CCA, radial scars (presence or absence), and number of AH foci. Extent of lobular involution was evaluated in the normal background breast lobules and classified as no involution (0% terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs) involuted), partial (1–74% involuted), or complete (>75% involuted).16

Breast Density

The clinical BI-RADS four-category tissue composition assessment was obtained from mammograms within twenty-four months prior to BBD diagnosis. Over the 1997–2001 period, the 3rd edition of the American College of Radiology BI-RADS was used, classifying the breast density into one of four categories: entirely fat; scattered fibroglandular densities; heterogeneously dense; and extremely dense.12 This rating has shown moderate interobserver reliability.17

Statistical Analysis

Variables from both models were summarized using frequencies and percent’s for categorical variables, and medians and ranges for continuous variables. We compared subjects in the BBD cohort during the study period (1997–2001) with and without a mammogram, using chi-square and Kruskal-Wallis tests of significance for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Similar comparisons were made across unaffected women, those with invasive BC, and those with DCIS.

Follow-up was calculated as the number of days from benign biopsy to the first occurrence of invasive BC, DCIS, death, prophylactic mastectomy, reduction mammoplasty, LCIS, or last contact. To be consistent with the methods used during each model’s development, DCIS was treated as a censoring event when estimating risk using the BCSC model, but as an outcome when using the BBD-BC model.

Both models were examined on the sample of women with a screening mammogram. For the BBD-BC model, the entire cohort over the 1997–2001 period was also examined since breast density is not required in this model. Individual 5 and 10 year risk predictions were calculated using both models. Each model’s ability to predict the total number of events (calibration) and distinguish future cases from controls (discrimination) was assessed.

Calibration was defined as the ratio of predicted-to-observed events, with the number of observed equaling the total number of events. The number of predicted events was estimated using methods described by Crowson18, et al. Briefly, the predicted risk was transformed using the formula

The number of predicted events was estimated by taking the sum of the transformed risk value on the study sample, and the confidence interval was calculated using bootstrapping19 methods on the number of predicted events. Discrimination was evaluated using the concordance statistic (c-statistic), a measure from 0 to 1.0 which evaluates the probability that a random case has a higher estimated risk than a random control. A value of 0.5 means the model predicts the outcome no better than chance; 1.0 means perfect discrimination. Time to event was modeled two ways: 1) right censoring BC events at 5 and 10 years and 2) using Cox proportional hazards regression with the predicted risk from each model as the independent variable. The proportional hazards assumption was verified for each model.

The proportion of women classified with high absolute risk was estimated using each of the two models, with an a priori selected threshold of 3% for 5-year risk20 and 8% for 10-year risk.21 The c-statistic and corresponding confidence interval were obtained from the ‘coxph’ function using the ‘survival’ package in R.22 All remaining analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.4.

Results

Study Population

Of 2,142 women from Mayo Clinic’s BBD Cohort years 1997–2001, 1211 (56.5%) had a screening mammogram 24 months prior to BBD, 409 (19.1%) had only a diagnostic mammogram during this period, 15 (0.7%) had a mammogram greater than 24 months prior to BBD, 240 (11.2%) had a screening/diagnostic mammograms only after BBD diagnosis, and 267 (12.5%) had no mammogram available. Of the 1211 with a screening mammogram 24 months prior to BBD, 1089 were aged 35–74 and eligible for the BCSC model. Women with a screening mammogram had longer follow-up (median 13.5 yrs. vs 11.4 yrs.), were older at initial biopsy (median 53 yrs. to 47 yrs.), and had higher proportions of AH (11.9% vs 6.8%), complete involution (42.1% vs 36.9%), and CCA/SA (49.5% vs 37.6%) than those without (Table 1).

Table 1.

Model Input Characteristics by Presence In The Screening Mammogram Cohort

| Characteristic | Women Without A Screening Mammogram 2 Years or Less Prior to BBD or Not Aged 35–74 N=1055 | Women Aged 35–74 With A Screening Mammogram 2 years or less prior to BBD N=1089 | Total N=2142 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of follow-up | <0.001 † | |||

| N | 1053 | 1089 | 2142 | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 11.4 (8.3, 14.8) | 13.5 (9.5, 15.3) | 12.4 (8.9, 15.1) | |

| Range | 0.5, 18.4 | 0.5, 18.4 | 0.5, 18.4 | |

| Year of BBD | 0.071 ‡ | |||

| 1997 | 215 (20.4%) | 218 (20.0%) | 433 (20.2%) | |

| 1998 | 245 (23.3%) | 206 (18.9%) | 451 (21.1%) | |

| 1999 | 211 (20.0%) | 219 (20.1%) | 430 (20.1%) | |

| 2000 | 200 (19.0%) | 220 (20.2%) | 420 (19.6%) | |

| 2001 | 182 (17.3%) | 226 (20.8%) | 408 (19.0%) | |

| Age of BBD | <0.001 † | |||

| N | 1053 | 1089 | 2142 | |

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 47 (36, 62) | 53 (45, 63) | 50 (42, 62) | |

| Range | 18, 85 | 35, 74 | 18, 85 | |

| Race | 0.233 ‡ | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 982 (93.3%) | 1033 (94.9%) | 2015 (94.1%) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 9 (0.9%) | 13 (1.2%) | 22 (1.0%) | |

| Asian * | 14 (1.3%) | 8 (0.7%) | 22 (1.0%) | |

| American Indian ** | 4 (0.4%) | 1 (0.1%) | 5 (0.2%) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (0.7%) | 8 (0.7%) | 15 (0.7%) | |

| Other/Mixed/Unknown *** | 37 (3.5%) | 26 (2.4%) | 63 (2.9%) | |

| No. First degree relatives w/BC | 0.126 ‡ | |||

| No FDR relatives | 651 (61.8%) | 669 (61.4%) | 1320 (61.6%) | |

| 1+ FDR relatives | 185 (17.6%) | 223 (20.5%) | 408 (19.0%) | |

| Unknown | 217 (20.6%) | 197 (18.1%) | 414 (19.3%) | |

| Family History of BC (1–3 degree) | 0.403 ‡ | |||

| Missing | 0 | 197 | 197 | |

| None | 510 (48.4%) | 449 (50.3%) | 959 (49.3%) | |

| Any | 543 (51.6%) | 443 (49.7%) | 986 (50.7%) | |

| Overall impression | <0.001 ‡ | |||

| NP | 636 (60.4%) | 543 (49.9%) | 1179 (55.0%) | |

| PDWA | 345 (32.8%) | 416 (38.2%) | 761 (35.5%) | |

| AH | 72 (6.8%) | 130 (11.9%) | 202 (9.4%) | |

| Number of atypical foci | <0.001 ‡ | |||

| 0 | 981 (93.2%) | 959 (88.1%) | 1940 (90.6%) | |

| 1 | 31 (2.9%) | 76 (7.0%) | 107 (5.0%) | |

| 2 | 21 (2.0%) | 30 (2.8%) | 51 (2.4%) | |

| 3+ | 20 (1.9%) | 24 (2.2%) | 44 (2.1%) | |

| Involution | <0.001 ‡ | |||

| Missing | 192 | 153 | 345 | |

| None | 176 (20.4%) | 127 (13.6%) | 303 (16.9%) | |

| Partial | 367 (42.6%) | 415 (44.3%) | 782 (43.5%) | |

| Complete | 318 (36.9%) | 394 (42.1%) | 712 (39.6%) | |

| Radial scars | 0.086 ‡ | |||

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Absent | 1014 (96.3%) | 1031 (94.8%) | 2045 (95.5%) | |

| Present | 39 (3.7%) | 57 (5.2%) | 96 (4.5%) | |

| SA/CCA | <0.001 ‡ | |||

| Neither | 657 (62.4%) | 550 (50.5%) | 1207 (56.3%) | |

| SA and/or CCA | 396 (37.6%) | 539 (49.5%) | 935 (43.7%) | |

| Age first live birth/No. Children | 0.550 ‡ | |||

| Missing | 265 | 237 | 502 | |

| <21, 1+ | 165 (20.9%) | 183 (21.5%) | 348 (21.2%) | |

| >=21, 3+ | 196 (24.9%) | 235 (27.6%) | 431 (26.3%) | |

| >=21, 1–2 | 303 (38.5%) | 304 (35.7%) | 607 (37.0%) | |

| Nulliparous | 124 (15.7%) | 130 (15.3%) | 254 (15.5%) |

BBD=benign breast disease; FDR=first degree relative; BC=breast cancer; NP=non-proliferative disease; PDWA=proliferative disease without atypia; AH=atypical hyperplasia; SA=sclerosing adenosis; CCA=columnar cell alterations.

The statistics are frequency (percent) for categorical variables and median (quartile 1, quartile 3) for continuous variables.

includes Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander

includes Alaska Native

treated as white

Wilcoxon

Chi-square

In the overall cohort, 162 invasive or in situ cancers were observed over 6.7 years median follow-up. The median follow-up of unaffected and BC cases was 12.4 years. In the screening cohort, 74 invasive BCs were observed over a median follow-up of 6.9 years, and 98 invasive BCs or DCIS occurred over a median follow-up of 7.1 years. The distribution of risk factors was similar to previously published reports of the overall Mayo Clinic BBD Cohort.2,7 Compared to women without invasive BC, women with invasive BC were more likely to have had AH (29.7% to 10.6%) and a greater number of AH foci (16.2% two or more foci to 4.2% two or more foci) (Table 2). The same associations were observed when women with DCIS were grouped with the invasive BCs and compared to the unaffected.

Table 2.

Model Input Characteristics by Invasive or In Situ Breast Cancer In The Screening Cohort

| Unaffected or DCIS N=1015 | Invasive Breast Cancer N=74 | p-value | Unaffected N=991 | DCIS or Invasive Breast Cancer N=98 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||

| Duration of follow-up, Median | 13.7 (9.8, 15.6) | 6.9 (4.8, 10.5) | <0.001 † | 13.8 (10.0, 15.6) | 7.1 (4.7, 10.5) | <0.001 † |

| Year of BBD | 0.210 ‡ | 0.380 ‡ | ||||

| 1997 | 199 (19.6%) | 19 (25.7%) | 196 (19.8%) | 22 (22.4%) | ||

| 1998 | 194 (19.1%) | 12 (16.2%) | 189 (19.1%) | 17 (17.3%) | ||

| 1999 | 202 (19.9%) | 17 (23.0%) | 195 (19.7%) | 24 (24.5%) | ||

| 2000 | 212 (20.9%) | 8 (10.8%) | 207 (20.9%) | 13 (13.3%) | ||

| 2001 | 208 (20.5%) | 18 (24.3%) | 204 (20.6%) | 22 (22.4%) | ||

| Variables in both BCSC and BBD-BC models | ||||||

| Age of BBD, Median | 53 (45, 63) | 54 (47, 64) | 0.452 † | 53 (45, 63) | 55 (47, 64) | 0.437 † |

| Overall impression | <0.001 ‡ | <0.001 ‡ | ||||

| NP | 513 (50.5%) | 30 (40.5%) | 506 (51.1%) | 37 (37.8%) | ||

| PDWA | 394 (38.8%) | 22 (29.7%) | 383 (38.6%) | 33 (33.7%) | ||

| AH | 108 (10.6%) | 22 (29.7%) | 102 (10.3%) | 28 (28.6%) | ||

| BCSC model specific variables | ||||||

| BI-RADS | 0.297 § | 0.239 § | ||||

| Entirely fat | 48 (4.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | 47 (4.7%) | 2 (2.0%) | ||

| Scattered fibroglandular densities | 376 (37.0%) | 23 (31.1%) | 369 (37.2%) | 30 (30.6%) | ||

| Heterogeneously dense | 426 (42.0%) | 34 (45.9%) | 415 (41.9%) | 45 (45.9%) | ||

| Extremely dense | 165 (16.3%) | 16 (21.6%) | 160 (16.1%) | 21 (21.4%) | ||

| Race | 0.788 ‡ | 0.662 ‡ | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 961 (94.7%) | 72 (97.3%) | 937 (94.6%) | 96 (98.0%) | ||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 13 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Asian * | 8 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| American Indian ** | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Hispanic | 7 (0.7%) | 1 (1.4%) | 7 (0.7%) | 1 (1.0%) | ||

| Other/Mixed/Unknown *** | 25 (2.5%) | 1 (1.4%) | 25 (2.5%) | 1 (1.0%) | ||

| Number First degree relatives w/BC | 0.033 ‡ | 0.003 ‡ | ||||

| No FDR relatives | 622 (61.3%) | 47 (63.5%) | 607 (61.3%) | 62 (63.3%) | ||

| 1+ FDR relatives | 202 (19.9%) | 21 (28.4%) | 194 (19.6%) | 29 (29.6%) | ||

| Unknown | 191 (18.8%) | 6 (8.1%) | 190 (19.2%) | 7 (7.1%) | ||

| BBD-BC specific variables | ||||||

| Number of atypical foci | <0.001 ‡ | <0.001 ‡ | ||||

| 0 | 907 (89.4%) | 52 (70.3%) | 889 (89.7%) | 70 (71.4%) | ||

| 1 | 66 (6.5%) | 10 (13.5%) | 62 (6.3%) | 14 (14.3%) | ||

| 2 | 24 (2.4%) | 6 (8.1%) | 22 (2.2%) | 8 (8.2%) | ||

| 3+ | 18 (1.8%) | 6 (8.1%) | 18 (1.8%) | 6 (6.1%) | ||

| Involution | 0.619 ‡ | 0.472 ‡ | ||||

| Missing | 137 | 16 | 131 | 22 | ||

| None | 119 (13.6%) | 8 (13.8%) | 115 (13.4%) | 12 (15.8%) | ||

| Partial | 386 (44.0%) | 29 (50.0%) | 378 (44.0%) | 37 (48.7%) | ||

| Complete | 373 (42.5%) | 21 (36.2%) | 367 (42.7%) | 27 (35.5%) | ||

| Radial scars | 0.251 ‡ | 0.375 ‡ | ||||

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Absent | 963 (95.0%) | 68 (91.9%) | 940 (94.9%) | 91 (92.9%) | ||

| Present | 51 (5.0%) | 6 (8.1%) | 50 (5.1%) | 7 (7.1%) | ||

| SA/CCA | 0.292 ‡ | 0.245 ‡ | ||||

| Neither | 517 (50.9%) | 33 (44.6%) | 506 (51.1%) | 44 (44.9%) | ||

| SA and/or CCA | 498 (49.1%) | 41 (55.4%) | 485 (48.9%) | 54 (55.1%) | ||

| Age first live birth/No. Children | 0.535 ‡ | 0.312 ‡ | ||||

| Missing | 235 | 2 | 235 | 2 | ||

| <21, 1+ | 169 (21.7%) | 14 (19.4%) | 168 (22.2%) | 15 (15.6%) | ||

| >=21, 3+ | 210 (26.9%) | 25 (34.7%) | 202 (26.7%) | 33 (34.4%) | ||

| >=21, 1–2 | 282 (36.2%) | 22 (30.6%) | 270 (35.7%) | 34 (35.4%) | ||

| Nulliparous | 119 (15.3%) | 11 (15.3%) | 116 (15.3%) | 14 (14.6%) | ||

| Family History of BC (1–3 degree) | 0.020 ‡ | 0.002 ‡ | ||||

| Missing | 191 | 6 | 190 | 7 | ||

| None | 424 (51.5%) | 25 (36.8%) | 417 (52.1%) | 32 (35.2%) | ||

| Any | 400 (48.5%) | 43 (63.2%) | 384 (47.9%) | 59 (64.8%) | ||

| 5-year risk, Median | ||||||

| Expected (from Iowa SEER) | 1.6 (1.1, 2.2) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.3) | 0.452 † | 1.6 (1.1, 2.2) | 1.7 (1.2, 2.3) | 0.437 † |

| BCSC | 2.2 (1.3, 3.3) | 2.7 (1.8, 4.0) | 0.002 † | 2.1 (1.3, 3.3) | 2.7 (1.9, 3.7) | <0.001 † |

| BBD-BC | 2.1 (1.5, 3.2) | 3.0 (1.7, 5.8) | 0.001 † | 2.1 (1.5, 3.2) | 3.0 (1.7, 5.8) | <0.001 † |

| 10-year risk, Median | ||||||

| Expected (from Iowa SEER) | 3.4 (2.5, 4.7) | 3.6 (2.7, 4.8) | 0.452 † | 3.4 (2.5, 4.7) | 3.7 (2.7, 4.8) | 0.437 † |

| BCSC | 4.7 (3.0, 6.6) | 5.6 (4.0, 8.0) | 0.001 † | 4.7 (3.0, 6.5) | 5.7 (4.1, 7.7) | <0.001 † |

| BBD-BC | 4.4 (3.1, 6.5) | 6.0 (3.5, 11.1) | 0.001 † | 4.3 (3.1, 6.5) | 5.9 (3.5, 11.1) | <0.001 † |

DCIS=ductal carcinoma in situ; BBD=benign breast disease; No.=Number; FDR=first degree relative; BC=breast cancer; NP=non-proliferative disease; PDWA=proliferative disease without atypia; AH=atypical hyperplasia; BI-RADS=Breast Imaging and Reporting System; SA=sclerosing adenosis; CCA=columnar cell alterations; BCSC= Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; BBD-BD= Benign Breast Disease to Breast Cancer.

The statistics are frequency (percent) for categorical variables and median (quartile 1, quartile 3) for continuous variables

includes Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander

includes Alaska Native

treated as white

Wilcoxon

Chi-square

Fisher exact

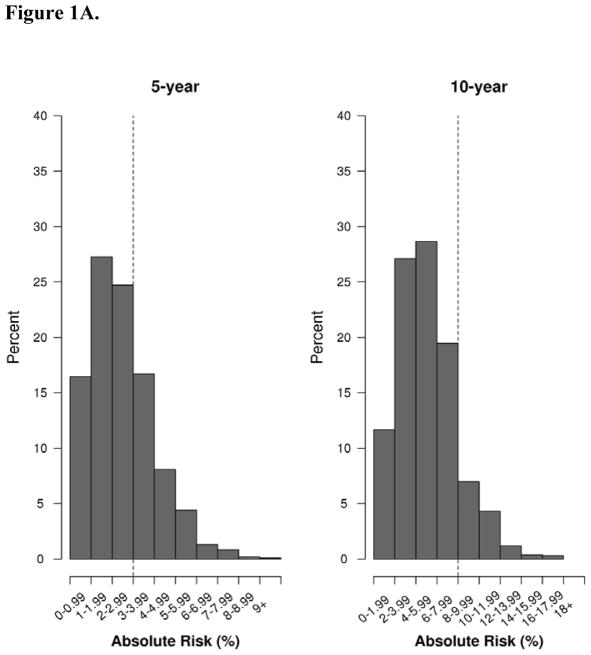

Performance of the BCSC Model

Fifty-four invasive BCs were diagnosed within 10 years of follow-up, with 20 occurring within 5 years and the remaining 34 between 5–10 years (Table 3). The median 5-year risk predicted using the BCSC was 2.7% for invasive cancers and 2.2% for the unaffected/DCIS (Table 2, Figure 1A). At 10 years, median BCSC predicted risk for invasive cancers and unaffected/DCIS were 5.6% and 4.7%. At 5-years post biopsy, the BCSC model achieved a discrimination that was not statistically better than chance (c-statistic = 0.59; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.71) and slightly over-estimated the number of events by 31% (predicted-to-observed ratio=1.31; 95% CI0.94 to 2.25), although there was no statistical difference as the confidence interval contained 1.0. At 10 years, the calibration was excellent (0.94; 95% CI, 0.85 to 1.43) and the c-statistic was now significantly better than 0.5 (0.63; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.71), indicating improved performance compared to 5 years.

Table 3.

Model Performance of the BCSC and BBD-BC Models

| BCSC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | N | Concordance Invasive BC (%) | C-statistic (95% CI) | Observed Events | Calibration Predicted Events | Pred./Obs. (95% CI) |

| Screening Cohort* | ||||||

| 5 years | 1089 | 20 (1.8%) | 0.59 (0.46, 0.71) | 20 | 26.12 | 1.31 (0.94, 2.25) |

| 10 years | 1089 | 54 (5.0%) | 0.63 (0.56, 0.71) | 54 | 51.02 | 0.94 (0.85, 1.43) |

| BBD-BC | ||||||

| Endpoint | N | Concordance Invasive or DCIS BC (%) | C-statistic (95% CI) | Calibration Observed Events | Predicted Events | Pred./Obs. (95% CI) |

| Screening Cohort* | ||||||

| 5 years | 1089 | 27 (2.5%) | 0.69 (0.58, 0.80) | 27 | 29.93 | 1.11 (0.84, 1.77) |

| 10 years | 1089 | 69 (6.3%) | 0.66 (0.59, 0.73) | 69 | 57.54 | 0.83 (0.77, 1.20) |

| Full BBD Cohort** | ||||||

| 5 years | 2142 | 56 (2.6%) | 0.68 (0.60, 0.75) | 56 | 49.70 | 0.89 (0.71, 1.21) |

| 10 years | 2142 | 118 (5.5%) | 0.66 (0.60, 0.71) | 118 | 95.34 | 0.81 (0.70, 1.00) |

BCSC= Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium; BBD-BD= Benign Breast Disease to Breast Cancer; DCIS=ductal carcinoma in situ; BC=Breast Cancer; Pred. = Predicted; Obs. = Observed;

Screening cohort, n=1089 ages 35–74 and with mammogram;

Full cohort, n=2142, ages 18 and up

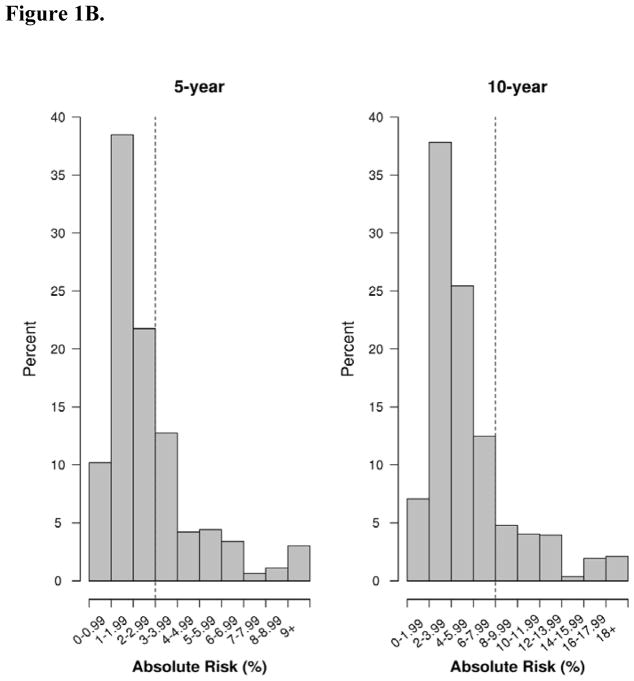

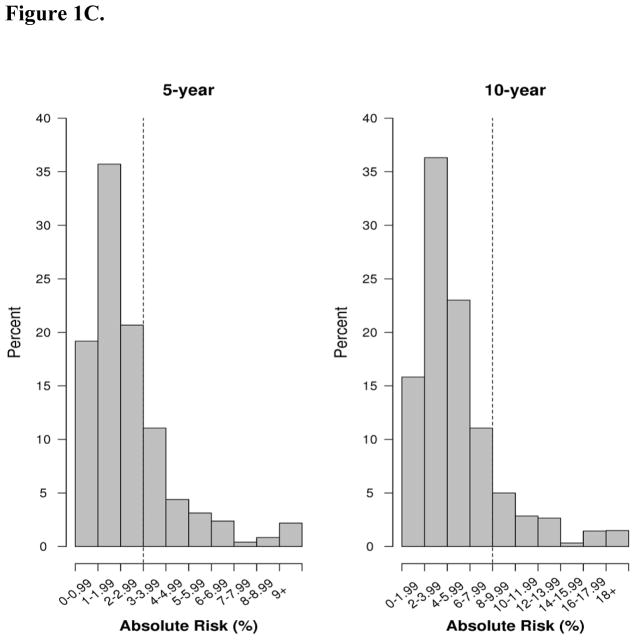

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Distribution of predicted absolute risk (%) at 5 and 10 year endpoints for the BCSC model in the screening cohort, 1997–2001. BCSC= Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Dotted lines reflect thresholds for risk of 3% for 5-year risk models and 8% for 10-year risk models.20

Figure 1B. Distribution of predicted absolute risk (%) at 5 and 10 year endpoints for the BBD- BC model in the screening cohort, 1997–2001. BBD-BD = Benign breast disease to breast cancer. Dotted lines reflect thresholds for risk of 3% for 5-year risk models and 8% for 10- year risk models.20

Figure 1C. Distribution of predicted absolute risk (%) at 5 and 10 year endpoints for the BBD- BC model in the full BBD cohort, 1997–2001. BBD-BD = Benign breast disease to breast cancer. Dotted lines reflect thresholds for risk of 3% for 5-year risk models and 8% for 10- year risk models.20

Performance of the BBD-BC Model in the Screening Cohort and Full Cohort

The BBD-BC model performed similarly well in the mammographic screening cohort at 5 and 10 years post-biopsy (Table 3). There were 27 events (DCIS and invasive cancer) at 5 years and an additional 42 cancers between 5–10 years. The calibration was 1.11 (95% CI, 0.84 to 1.77) at 5 years, with a c-statistic of 0.69 (95% CI, 0.58 to 0.80). At 10 years, the calibration was slightly underestimated at 0.83 (95% CI, 077 to 1.20) but not statistically significant, and the c-statistic was 0.66 (95% CI, 0.59 to 0.73) (Table 3). Median 5-year predicted risk using the BBD-BC model was 3.0% for women who developed DCIS/invasive cancer and 2.1% for unaffected women. Median 10 year predicted risk estimates were 5.9% and 4.3% (Figure 1B, Table 2).

Among the entire cohort of 2,142 with BBD between 1997–2001, there were 56 cancers within 5 years and 62 additional between 5 and 10 years (for 118 total). Performance of the BBD-BC model in the overall cohort was generally similar to that screening cohort, however, the calibration for ten-year risk showed greater evidence of underestimation of predicted risk in the overall cohort. In the overall cohort, the calibration of the BBD-BC model was 0.89 (95% CI 0.71 to 1.21) at 5 years, and the c-statistic was 0.68 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.75). At 10 years, the calibration was 0.81 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.00) and the c-statistic was 0.66 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.71) (Table 3). Median 5-year predicted risk using the BBD- was 2.5% for women who developed DCIS/invasive cancer and 1.8% for unaffected women. Median 10 year predicted risk estimates were 5.0% and 3.8% (Figure 1C).

Estimated Absolute Breast Cancer Risks Predicted by BCSC and BBD-BC Models

Thresholds of absolute risk of cancer can be used to classify women at the greatest risk of BC as well as define who may receive the greatest benefit from prevention strategies.20 The BCSC model predicted that 31.6% (344 women) exceeded a 5-year risk of 3% and 13.1% (143 women) were above a 10-year risk of 8% (Fig 1: Supplemental Table 1). Of the 344 with 5-year risk above the 3% threshold, 2.6% developed invasive BC within 5 years; 10.5% of the 143 with 10-year risk above 8% developed invasive BC within 10-years. When using the BBD-BC model on the screening cohort, a similar proportion of women (31.1% or 339) exceeded 5-year risk of 3%, and of the 339 predicted to be at high risk, 4.4% developed DCIS or invasive cancer during the five years. Using 10-year risk predictions, 194 women (17.8%) were at high risk, of which 12.4% of these developed cancer.

When examining the BBD-BC model on all women with BBD diagnosed between 1997–2001, 523 women (24.4%) had predicted risk above the 3% threshold. Of these 523, 4.8% developed DCIS or invasive BC within 5 years. Similarly, at 10 years 295 women (13.8%) had predicted risk above the threshold of 8%, of which 10.5% were diagnosed with cancer within 10 years.

Discussion

Over 1 million women have BBD each year, which places them at a greater risk of breast cancer relative to the general population.2 Women with BBD require counseling regarding their risk and models appropriate to the BBD population are needed. We evaluated the updated BCSC and BBD-BC models for prediction of breast cancer risk at 5 and 10 years of follow-up in women with BBD. We found that the BCSC model correctly predicted the number of events at 5-years post biopsy but had low discrimination (no different than chance). However, at 10 years, discrimination was higher, and the calibration remained accurate. In the overall cohort and the screening cohort (with mammograms), the BBD-BC model performed well at five years, but under estimated events at ten years in the entire cohort, although this was only borderline statistically significant. Importantly, this study was performed on a subset of the Mayo Clinic BBD cohort that was mutually exclusive of the prior BBD-BC model development and validation sets. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the performance of these models in a cohort of women with BBD.

Other than age and BBD diagnosis, the BCSC and BBD-BC models share few risk factors. The BBD-BC model includes four histologic assessments of the biopsy based on expert review, whereas the BCSC includes the final pathologic diagnosis from reports. The BCSC includes BI-RADS density and race while the BBD-BC incorporates neither, although the Mayo population is primarily Caucasian.10 Further, BBD-BC includes more extensive family history of BC (first- through third-degree) than the BCSC (first degree). Finally, the treatment of LCIS differed.

In addition to risk factors, the models differ based on their initial development population. The BBD-BC was developed and validated on women with a confirmed BBD diagnosis, regardless of prior breast screening or breast density availability. It is intended for use in the woman with a benign biopsy resulting from a screening abnormality or palpable concern and at the time of BBD diagnosis.7 The BCSC model, though, was initially developed for women with screening mammography and later expanded to include findings on benign biopsies, but was never validated in this latter population.8 Due to the requirement for a breast density measure, the BCSC cannot be used for women without an available mammogram.

The two models performed differentially at five and ten years. At 5 years post-biopsy, the BCSC model had lower discrimination than at ten years; while at ten years, the BBD-BC model showed underestimation of observed events (calibration) in the entire cohort. Although we cannot make a direct comparison of the models due to the differential treatment of LCIS and DCIS in the development of the models, the higher model discrimination and calibration for the BBD-BC at 5 years could suggest that histologic aspects might better inform shorter term risk and/or contribute to DCIS prediction for women with BBD.

Using the 5-year risk prediction from the two models, approximately 31% of women having screening mammograms exceeded our a priori defined threshold of 3%, as defined by the United States Prevention Services Task Force as the threshold for women who receive maximum benefit from chemoprevention.20 Of the 31% identified as high risk, between 2–4% developed cancers that may have been avoided with chemoprevention. At 10 years of follow-up, 13%-18% of women would have been offered prevention, and 11–12% of such women would have developed cancer. However, 1–5% of women at lower risk (under 3% 5-year risks or under 8% 10-year risk), comprising the majority of women, also developed cancer. Clearly, improvement in models for women with BBD is necessary.

There are several strengths to this study, including the evaluation of these models in a well-annotated cohort with long-term follow-up. All women had their pathology reviewed by the same experienced breast pathologist who was masked to later BC status. Additionally, the subcohort used in this study was independent of the development sets for both models, thus providing an external validation. Mayo Clinic’s unified medical record, tumor registry database, and questionnaires of study participants provided detailed information on clinical and demographic attributes, and post-biopsy follow-up for cancer events. This work provides external evaluation for two recently published models.7–9

We also recognize there are limitations to this work. First, we were unable to directly compare the two models due to differences in BC outcomes, i.e. DCIS was not included in BCSC model. Next, our work focused on examining the BCSC and BBD-BC models due to their inclusion of histologic findings on biopsy, and did not examine other risk models in this setting. Further, only women aged 35–74 with a screening mammogram prior to BBD up to 24 months (51% of the entire cohort) were included when analyzing the screening cohort due to BCSC eligibility. We had incomplete ascertainment as 9% of our sample left the Mayo Health Care system or did not respond to a questionnaire over the ten year follow-up period.

However, 95% of women had at least five years follow-up, so misclassification of endpoints should have minimally affected model performance at 5-years. Importantly, the BCSC was developed in a multi-ethnic population while the BBD study sample was not racially diverse.

Finally, we acknowledge that the women in this study were more similar to the development set of the BBD- BC model than the BCSC, as they were sampled from the same population cohort, using the same eligibility criteria and at the time of biopsy. While the study sample in this work was mutually exclusive from the women used to develop the BBD-BC model, the samples were read by the same pathologist (DWV) in this more recent cohort. Demographic characteristics are likely more similar to samples used to develop the BBD-BC model than the study sample used to create the BCSC model. If the same examination were made using the same population, biopsies and pathologies from the BCSC model, it is possible that the BCSC would have had a higher discrimination.

Conclusion

The BCSC model was validated in the Mayo BBD Cohort, and performed well at 10 years post-biopsy while the BBD-BC model showed better performance at the five-year time point. More study is needed to more accurately predict BC risk in women with BBD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the participants within the Mayo BBD study and Ms. Michelle Lewis for her editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: Each author has completed their disclosure and contribution forms.

Conflicts of Interest: No authors report conflicts of interest

Research Support: Mayo Clinic Cancer Center; Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer SPORE P50, CA116201; National Cancer Institute R01 CA187112; National Cancer Institute R21 CA186734.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: RF, MF, KG, KB, DV and CV. Methodology: RF, RV, MF, KG, DV, AD, and CV. Software: RF. Validation: RF and CV. Formal analysis: RF, SW and RV. Investigation: RV, MF, DV, AD and CV. Resources: RF, MF, DV, LH, AD and CV. Data Curation: RF and RV. Writing-original draft: RF, SW, RV, and CV. Writing-review and editing: MS, RF, SW, RV, MF, DR, KG, KB, DV, LH, AD, and CV. Visualization: RF and CV. Supervision: SW, MF, AD, and CV. Project Administration: CV, MF. Funding acquisition: DV, AD and CV.

References

- 1.Silverstein M. Where’s the outrage? Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2009;208(1):78–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams-Campbell LL, Makambi KH, Frederick WA, Gaskins M, DeWitty RL, McCaskill-Stevens W. Breast Cancer Risk Assessments Comparing Gail and CARE Models in African-American Women. Breast J. 2009;15(s1):S72–S75. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2009.00824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(24):1879–1886. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.24.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockhill B, Spiegelman D, Byrne C, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA. Validation of the Gail et al. model of breast cancer risk prediction and implications for chemoprevention. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(5):358–366. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.5.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pankratz VS, Hartmann LC, Degnim AC, et al. Assessment of the accuracy of the Gail model in women with atypical hyperplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5374–5379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pankratz VS, Degnim AC, Frank RD, et al. Model for individualized prediction of breast cancer risk after a benign breast biopsy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(8):923–929. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Kerlikowske K. Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148(5):337–347. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tice JA, Miglioretti DL, Li C-S, Vachon CM, Gard CC, Kerlikowske K. Breast density and benign breast disease: risk assessment to identify women at high risk of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(28):3137–3143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vachon CM, Pankratz VS, Scott CG, et al. The contributions of breast density and common genetic variation to breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(5):dju397. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visscher DW, Nassar A, Degnim AC, et al. Sclerosing adenosis and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2014;144(1):205–212. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2862-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American College of Radiology. The American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data Systems (BI-RADS) 3. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dupont WD, Page DL. Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(3):146–151. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Page D. Atypical hyperplastic lesions of the female breast: A long-term follow-up study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;77(4):688. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Page DL, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, Jensen RA, Plummer WD, Simpson JF. Atypical lobular hyperplasia as a unilateral predictor of breast cancer risk: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2003;361(9352):125–129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milanese TR, Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, et al. Age-related lobular involution and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(22):1600–1607. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spayne MC, Gard CC, Skelly J, Miglioretti DL, Vacek PM, Geller BM. Reproducibility of BI-RADS Breast Density Measures Among Community Radiologists: A Prospective Cohort Study. Breast J. 2012;18(4):326–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2012.01250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crowson CS, Atkinson EJ, Therneau TM. Assessing calibration of prognostic risk scores. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25(4):1692–1706. doi: 10.1177/0962280213497434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haukoos JS, Lewis RJ. Advanced statistics: bootstrapping confidence intervals for statistics with “difficult” distributions. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(4):360–365. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moyer VA Force USPST. Medications to decrease the risk for breast cancer in women: recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):698–708. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans DG, Brentnall AR, Harvie M, et al. Breast cancer risk in young women in the National Breast Screening Programme: implications for applying NICE guidelines for additional screening and chemoprevention. Cancer Prevention Research (Philadelphia, Pa) 2014;7(10):993–1001. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Therneau TM, Lumley T. Package ‘survival’. Verze: 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.