Abstract

Background

Patients with cancer experience many stressors placing them at risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, yet little is known about factors associated with PTSD symptoms in this population. We sought to explore relationships among patients’ PTSD symptoms, physical and psychological symptom burden, and risk for hospital readmissions.

Methods

We prospectively enrolled patients with cancer admitted for an unplanned hospitalization from August 2015-April 2017. Upon admission, we assessed patients’ PTSD symptoms (Primary Care PTSD Screen), as well as physical (Edmonton Symptom Assessment System [ESAS]) and psychological (Patient Health Questionnaire 4 [PHQ-4]) symptoms. We examined associations between PTSD symptoms and patients’ physical and psychological symptom burden using linear regression. We evaluated relationships between PTSD symptoms and unplanned hospital readmissions within 90-days using Cox regression.

Results

We enrolled 954 of 1,087 (87.8%) patients approached, and 127 (13.3%) screened positive for PTSD symptoms. The 90-day hospital readmission rate was 38.9%. Younger age, female sex, greater comorbidities, and genitourinary cancer type were associated with higher PTSD scores. Patients’ PTSD symptoms were associated with physical symptoms (ESAS-physical: B=3.41, P<0.001), total symptom burden (ESAS-total: B=5.97, P<0.001), depression (PHQ4-depression: B=0.67, P<0.001) and anxiety symptoms (PHQ4-anxiety: B=0.71, P<0.001). Patients’ PTSD symptoms were associated with lower risk of hospital readmissions (HR=0.81, P=0.001).

Conclusions

A high proportion of hospitalized patients with cancer experience PTSD symptoms, which are associated with greater physical and psychological symptom burden, and lower risk for hospital readmissions. Interventions to address patients’ PTSD symptoms are needed and should account for their physical and psychological symptom burden.

Keywords: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Symptoms, Mood, Cancer, Outcomes Research, Hospital Readmissions

Introduction

Patients with cancer often experience numerous stressors, including the sudden and unexpected threat of a life-altering illness, uncertainty regarding their future, and perceived loss of control.1–3 In addition, the anticipation of facing adverse consequences associated with cancer and experiencing debilitating side effects from treatment can have traumatic repercussions for patients.4, 5 Notably, a cancer diagnosis may embody both an external and internal threat, which patients can perceive as inescapable and/or hopeless.6, 7 Therefore, patients with cancer represent a population uniquely vulnerable to experiencing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or suffering an exacerbation of pre-existing PTSD symptoms.

Previous research suggests that a substantial proportion of patients with cancer experience PTSD symptoms.8 For example, studies involving patients with breast cancer demonstrate that approximately 10% of patients experience PTSD symptoms, which are associated with worse quality of life.9–12 Among patients with hematologic malignancies who undergo stem cell transplantation, studies suggest that over 20% may report PTSD symptoms, which are associated with worse patient outcomes.13, 14 However, research is lacking regarding the rates of PTSD symptoms among patients with other types of cancer. In addition, despite evidence linking PTSD symptoms with patients’ psychological distress,8, 14–16 we lack information regarding associations between PTSD symptoms and patients’ physical symptom burden. Moreover, little data currently exist about the relationship between PTSD symptoms and healthcare utilization, such as hospital readmissions. Importantly, symptom flare-ups and the need for hospital-level care may serve as a reminder of the life-threatening nature of cancer, and thus may trigger a traumatic stress response among patients with cancer.5, 17

Although hospitalized patients with cancer often experience substantial physical and psychological symptom burden, information about PTSD symptoms among these patients is scarce.18 Therefore, in the present study, we prospectively collected patients’ self-reported PTSD symptoms to better understand the prevalence and associated factors of PTSD symptoms among hospitalized patients with cancer. We also sought to examine relationships between patients’ PTSD symptoms and their physical and psychological symptom burden. We hypothesized that patients who experience PTSD symptoms would report worse physical and psychological symptom burden. Additionally, we explored for associations between patients’ PTSD symptoms and their healthcare utilization (i.e. unplanned hospital readmissions). By studying the relationships among patients’ PTSD symptoms, physical and psychological symptoms, and healthcare utilization, we sought to understand the importance of PTSD symptoms in patients with cancer.

Methods

Study procedures

This study was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board. From 8/1/2015 to 4/20/2017, we enrolled patients with cancer and an unplanned hospital admission at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in a longitudinal cohort study. We identified and recruited consecutive patients who had an unplanned hospital admission (index hospitalization) during the study period by screening the daily inpatient oncology census. Each participant contributed one unique hospitalization. We obtained written, informed consent from eligible patients on the first weekday following admission (within 2-5 days of hospitalization). Following consent, participants completed a symptom burden questionnaire.

Participants

Patients eligible for study participation included those who were at least 18 years old and admitted to MGH with known diagnosis of cancer. Study participants also had to be able to read and respond to study questionnaires in English or with minimal assistance from an interpreter. We excluded patients with elective or planned hospital admissions, defined as hospitalizations for chemotherapy administration, scheduled surgical procedures, chemotherapy desensitization, or stem cell transplantation.

Study Measures

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

To obtain information about participants’ date of birth, sex, race, relationship status, education, and religion, we reviewed the demographics section of the EHR. Additionally, we used the EHR to review patients’ oncology clinic notes to determine the Charlson Comorbidity Index, date of cancer diagnosis, cancer type, and whether the patient had incurable or curable cancer. We defined patients with incurable cancer as those not being treated with curative intent based on the chemotherapy order entry treatment designation (palliative vs. curative) or per documentation in the oncology clinic notes for those not receiving chemotherapy.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms

We used the Primary Care-PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) to assess symptoms of post-traumatic stress, which has been utilized in both primary care and oncology populations.12, 19–21 The PC-PTSD is a 4-item screen with a binary (yes or no) response pattern designed to evaluate symptoms of PTSD.19 We asked patients, “When thinking about your illness with cancer, have you ever had any experience that was so frightening, horrible, or upsetting that, in the past month, you… a) Have had nightmares about it or thought about it when you did not want to?, b) Tried hard not to think about it or went out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of it?, c) Were constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled?, d) Felt numb or detached from others, activities, or your surroundings?” The PC-PTSD screen can be interpreted both continuously and dichotomously, with an affirmative response to any three or more questions, generating a score of ≥3, indicating a positive screen for PTSD symptoms.

Physical and Psychological Symptom Burden

We used the self-administered revised Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS-r) to assess patients’ symptoms.22 The ESAS-r assesses pain, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, appetite, dyspnea, depression, anxiety, and well-being over the previous 24-hours. We also included constipation, as this is a highly prevalent symptom among patients with cancer.23 Each individual symptom is scored on a 0-10 scale (0 reflecting absence of the symptom and 10 reflecting the worst possible severity). We categorized the severity of ESAS scores as none (0), mild (1-3), moderate (4-6), and severe (7-10), consistent with prior research.24 Additionally, we computed composite ESAS-physical and ESAS-total symptom variables, which include summated scores of patients’ physical (pain, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, appetite, dyspnea, constipation) and total symptoms (pain, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, appetite, dyspnea, depression, anxiety, wellbeing, constipation). These ESAS-physical and ESAS-total symptom variables are well-validated and have been utilized previously in the oncology setting.22, 25

We used the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) to assess participants’ psychological symptoms.26 The PHQ-4 is a 4-item tool with two 2-item subscales that evaluate depression and anxiety symptoms. Both subscales and the composite PHQ-4 can be evaluated continuously with higher scores indicating worse psychological distress.26

Healthcare Utilization

We sought to explore the relationship between patients’ PTSD symptoms and their risk of unplanned hospital readmissions. For this outcome, we used time to first unplanned hospital readmission within 90-days of hospital discharge. We used the 90-day time frame to account for possible mortality, recognizing that patients who die after their index hospitalization have less time at risk for hospital readmissions. We defined time to first unplanned hospital readmission as the number of days from hospital discharge to first unplanned hospital readmission within 90-days. We censored patients without a hospital readmission at their 90-day post-discharge date and those who died within 90-days at their death date.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to evaluate the frequencies, means, and standard deviations (SDs) for participants’ characteristics, PTSD symptoms, physical and psychological symptom burden, and their healthcare utilization measures. To explore relationships between participant characteristics and continuous PTSD scores, we used linear regression modeling with purposeful selection of covariates.27 For purposeful selection, we included covariates that were associated at a significance level <0.10 and any confounders (defined as any variable that changed the parameter estimate of another variable by >20% when removed from the model) into the final model. To examine relationships between continuous PTSD symptoms and patients’ physical and psychological symptom burden, we used linear regression models, adjusted for potential confounders, including age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index), cancer type, presence of incurable cancer, and time since cancer diagnosis.10, 28–34 We also used Fisher’s exact test to compare the rates of moderate/severe ESAS symptoms for patients with and without a positive screen for PTSD symptoms. To investigate the relationship between continuous PTSD symptoms and time to hospital readmission within 90-days, we used Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for potential confounders, including age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities, cancer type, presence of incurable cancer, time since cancer diagnosis, length of stay during the index hospital admission, PHQ4-depression symptoms, PHQ4-anxiety symptoms, and ESAS-physical symptoms.10, 28–34 All reported p-values are two-sided with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. We used SPSS for Windows version 20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) for statistical analyses.

Results

Participant Sample

We screened a total of 2,610 patients for eligibility (Figure 1). We approached 1,087 eligible patients, and 954 (87.8%) participants enrolled and provided data about PTSD symptoms (Figure 1). Only four participants did not complete the PC-PTSD screen. Participants (mean age=62.80 ± SD=13.50 years; median age=65.00, interquartile range=55.00-72.00) were primarily white (91.6%), married (63.1%), and educated beyond high school (55.5%) (Table 1). Gastrointestinal cancers (22.2%), lymphomas (19.0%), and leukemias (16.0%) were the most common cancer types. Participants had a median time since diagnosis of cancer of 11.79 months (interquartile range, 3.31-41.03) and approximately half (49.5%) had incurable cancer. The hospital readmission rate within 90 days was 38.9% in the sample.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Overall Cohort

|

|

|---|---|---|

| N = 954 | % | |

| Age - mean (SD) | 62.80 | 13.50 |

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 419 | 43.9 |

| Male | 535 | 56.1 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 874 | 91.6 |

| African American | 40 | 4.2 |

| Asian | 25 | 2.6 |

| Hispanic | 13 | 1.4 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 | 0.1 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.1 |

|

| ||

| Relationship status | ||

| Married or living with someone as if married | 602 | 63.1 |

| Single | 165 | 17.3 |

| Divorced | 111 | 11.6 |

| Widowed | 76 | 8.0 |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

| High school and below | 308 | 32.3 |

| Beyond high school | 529 | 55.5 |

| Declined to provide | 117 | 12.3 |

|

| ||

| Religion | ||

| Catholic | 466 | 48.8 |

| Non-Catholic, Christian | 294 | 30.8 |

| None | 133 | 13.9 |

| Jewish | 43 | 4.5 |

| Muslim | 5 | 0.5 |

| Other | 13 | 1.4 |

|

| ||

| Insurance | ||

| Government-sponsored | 490 | 51.4 |

| Private | 460 | 48.2 |

| None | 4 | 0.4 |

|

| ||

| Cancer Type | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 212 | 22.2 |

| Lymphoma | 181 | 19.0 |

| Leukemia | 153 | 16.0 |

| Lung | 106 | 11.1 |

| Genitourinary | 66 | 6.9 |

| Head and Neck | 62 | 6.5 |

| Breast | 53 | 5.6 |

| Skin | 49 | 5.1 |

| Sarcoma | 37 | 3.9 |

| Gynecologic | 32 | 3.4 |

| Unknown Primary | 3 | 0.3 |

|

| ||

| Diagnosed with incurable cancer | 472 | 49.5 |

|

| ||

| Months since cancer diagnosis – mean (SD) | 34.19 | 53.40 |

|

| ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index - mean (SD) | 0.87 | 1.27 |

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms

Participants had a mean PC-PTSD score of 0.99 (SD=1.19), and 13.3% (n=127) screened positive for PTSD symptoms. On the individual items, tried hard not to think about it or avoid situations that reminded you of it (30.6%) was most commonly endorsed, followed by nightmares about it or thought about it when you did not want to (26.5%), felt numb or detached (26.3%), and constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled (15.8%). Using linear regression, we found that younger age (B=−0.02, 95% CI: −0.02 to −0.01, p<0.001), female sex (B=0.21, 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.36, p=0.008), greater number of comorbidities (B=0.09, 95% CI: 0.03 to 0.15, p=0.005), and genitourinary cancer type (B=0.39, 95% CI: 0.09 to 0.69, p=0.011) were associated with higher PC-PTSD scores (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptoms

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariable* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% CI | P | B | SE | 95% CI | P | |

| Age | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 to −0.01 | <0.001 | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.02 to −0.01 | <0.001 |

| Female Sex | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.02 to 0.32 | 0.028 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.06 to 0.36 | 0.008 |

| White Race | −0.12 | 0.14 | −0.39 to 0.16 | 0.398 | ||||

| Married | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.19 to 0.12 | 0.668 | ||||

| Education Beyond High School | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.16 to 0.14 | 0.908 | ||||

| Government-Sponsored Insurance | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.28 to 0.02 | 0.087 | ||||

| Incurable cancer | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.07 to 0.23 | 0.314 | ||||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index Score | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 to 0.09 | 0.246 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.03 to 0.15 | 0.005 |

| Months Since Cancer Diagnosis | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.00 | 0.151 | ||||

| Cancer Type | ||||||||

| Gastrointestinal | −0.12 | 0.09 | −0.31 to 0.06 | 0.180 | ||||

| Lung | −0.26 | 0.12 | −0.50 to −0.02 | 0.035 | −0.23 | 0.12 | −0.47 to 0.01 | 0.063 |

| Breast | 0.23 | 0.17 | −0.10 to 0.56 | 0.175 | ||||

| GU | 0.27 | 0.15 | −0.03 to 0.57 | 0.076 | 0.39 | 0.15 | 0.09 to 0.69 | 0.011 |

| Head and Neck | 0.15 | 0.16 | −0.16 to 0.45 | 0.350 | ||||

| Lymphoma | −0.07 | 0.10 | −0.27 to 0.12 | 0.458 | ||||

| Leukemia | 0.05 | 0.11 | −0.16 to 0.25 | 0.649 | ||||

| Other¥ | 0.12 | 0.12 | −0.11 to 0.35 | 0.291 | ||||

Included all variables with p<0.30 from univariate.

Purposeful selection

Includes skin cancers, sarcomas, gynecologic malignancies, and cancer of unknown primary.

Relationship between PTSD Symptoms and Physical and Psychological Symptom Burden

Table 3 depicts the relationship between patients’ PTSD symptoms and their physical and psychological symptom burden after adjusting for age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities, cancer type, presence of incurable cancer, and time since cancer diagnosis. Patients’ PTSD symptoms were significantly associated with worse physical symptoms (ESAS-physical: B=3.41, 95% CI: 2.61 to 4.21, SE=0.41, P<0.001), total symptom burden (ESAS-total: B=5.97, 95% CI: 4.95 to 7.00, SE=0.52, P<0.001), depression symptoms (PHQ4-depression: B=0.67, 95% CI: 0.58 to 0.77, SE=0.05, P<0.001), and anxiety symptoms (PHQ4-anxiety: B=0.71, 95% CI: 0.62 to 0.80, SE=0.05, P<0.001).

Table 3.

Associations between Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Symptom Score and Patients’ Physical and Psychological Symptom Burden

| PTSD Symptom Score | B | 95% CI | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESAS Physical* | 3.41 | 2.61 to 4.21 | 0.41 | <0.001 |

| ESAS Total* | 5.97 | 4.95 to 7.00 | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-4 Depression* | 0.67 | 0.58 to 0.77 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-4 Anxiety* | 0.71 | 0.62 to 0.80 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

All models adjusted for age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities, cancer type, presence of incurable cancer, and time since cancer diagnosis.

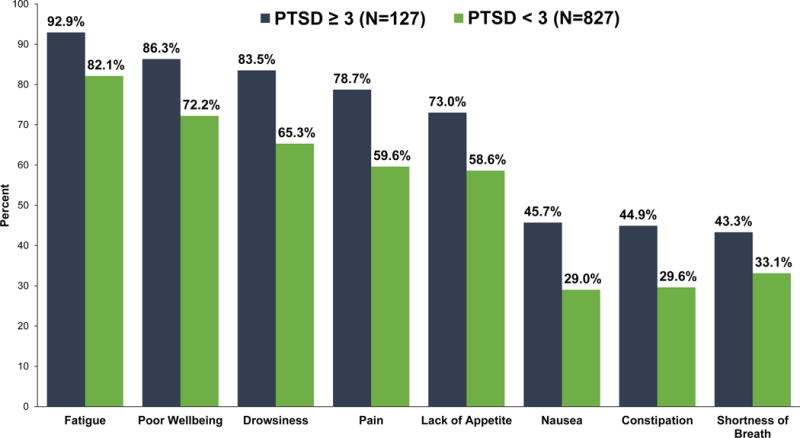

As shown in Figure 2, patients who screened positive for PTSD symptoms had higher rates of moderate/severe symptom burden. For example, patients who screened positive for PTSD symptoms had higher rates of moderate/severe fatigue (92.9% vs 82.1%, P=0.001), drowsiness (83.5% vs 65.3%, P<0.001), pain (78.7% vs 59.6%, P<0.001), and lack of appetite (73.0% vs 58.6%, P=0.002).

Figure 2.

Rates of Moderate to Severe Symptom Burden for Patients With and Without a Positive Screen for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms

P-value < 0.05 for all symptoms.

The Relationship between PTSD Symptoms and Healthcare Utilization

Patients’ PTSD symptoms were associated with lower risk of unplanned hospital readmissions within 90-days (HR=0.81, 95% CI: 0.72 to 0.91, SE=0.06, P<0.001) in Cox regression models adjusted for age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities, cancer type, presence of incurable cancer, time since cancer diagnosis, length of stay during the index hospital admission, PHQ4-depression symptoms, PHQ4-anxiety symptoms, and ESAS-physical symptoms.

Discussion

In this prospective study of hospitalized patients with cancer, we demonstrated that a substantial proportion of patients experience PTSD symptoms, and we identified participant characteristics associated with greater likelihood of experiencing these symptoms. Importantly, we also found that patients’ PTSD symptoms were significantly associated not only with their physical and psychological symptom burden but also with their healthcare utilization. Collectively, these findings provide important new evidence regarding the rates and correlates of PTSD symptoms, while also highlighting associations between these symptoms and other important patient outcomes.

Our work underscores the remarkably high rates of PTSD symptoms experienced by hospitalized patients with multiple types of cancer. Over 13% of patients met criteria for PTSD symptoms, which is higher than much of the prior work involving patients with cancer,10–12, 16, 35–37 and may be related to the study setting and the fact that we recruited patients with various types of cancer, including hematologic malignancies. A more complete understanding of the frequency and impact of PTSD symptoms among patients with cancer can be instrumental in: (1) identifying patients at higher risk for experiencing PTSD symptoms; (2) understanding how PTSD symptoms may influence patient outcomes; and (3) providing additional services targeted at the specific supportive care needs of these patients. Prior work suggests a relationship between patients’ PTSD symptoms and their quality of life, psychological distress, and coping strategies, and thus by not diagnosing and managing PTSD symptoms we miss an opportunity to enhance important patient outcomes.9–16, 38, 39 Additionally, by demonstrating the significant associations between PTSD symptoms and patients’ physical and psychological symptom burden, our work provides compelling evidence supporting the need for efforts to address PTSD symptoms when seeking to comprehensively manage patients’ symptom burden.

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to report that patients’ PTSD symptoms are associated with both their physical and psychological symptom burden, as well as their healthcare utilization. Although prior studies have highlighted that PTSD symptoms often correlate with psychological distress in patients with cancer,14–16 information about the relationship between PTSD symptoms and physical symptom burden was lacking. Patients’ physical symptoms may serve as a reminder of their cancer diagnosis, and in turn, this re-experiencing of symptoms may trigger PTSD symptoms such as intrusive thoughts, distress, and increased arousal.5, 17, 36, 37 Alternatively, greater endorsement of PTSD symptoms among patients with cancer may indicate a continued preoccupation with the illness and/or hypervigilance regarding physical symptoms as a sign of potential disease recurrence.17 Interestingly, we found that patients’ PTSD symptoms were associated with lower risk of unplanned hospital readmissions. This finding, although hypothesis-generating, may be related to the avoidance component of PTSD symptoms,14, 37, 40 as patients may seek to avoid places and circumstances that can arouse recollections of the trauma surrounding their cancer diagnosis. Clinically, the tendency of patients with greater PTSD symptoms to avoid hospitalizations may result in delayed care, which could also help explain why these individuals reported greater physical and psychological symptom burden upon presentation to the hospital. By demonstrating these novel findings regarding the associations among PTSD symptoms, patients’ physical and psychological symptom burden, and their healthcare utilization, we hope to highlight the need to develop interventions tailored to patients with cancer who report PTSD symptoms.

Of note, we identified patient characteristics associated with PTSD symptoms. Consistent with prior studies, younger and female patients had greater PTSD symptoms.10, 28 Research suggests that younger and female patients with cancer report greater unmet supportive care needs, and older patients may experience less emotional variation compared to younger patients.41–46 We also demonstrated a relationship between the number of patients’ comorbid conditions and greater PTSD symptoms, which may indicate the need to screen for these symptoms among patients with cancer and additional comorbid illnesses.47 Education level did not correlate with PTSD symptoms in our sample, in contrast to prior work, underscoring the importance of screening for PTSD symptoms, even in highly educated patients.10, 40 Intriguingly, we identified an association between PTSD symptoms and patients with genitourinary cancers. Additional research is warranted to help understand the mechanisms underlying this finding, and investigators should explore whether the types of treatments patients receive and/or the potential trauma related to the diagnosis and management may play a role. Ultimately, these findings help identify individuals at greater risk for PTSD symptoms and should inform future efforts to target these patients with supportive care interventions to address these symptoms.

This study has several limitations that merit discussion. First, we performed the study at a single, tertiary care site in a patient sample with limited socioeconomic diversity, and thus the findings may not generalize to more diverse populations or patients in different geographic areas. Additionally, most patients who receive their cancer care at our institution are admitted within our health system, and we tracked all hospital readmissions to any hospital within our health system. However, for the few patients who required hospitalization outside of our health system, we may be underestimating readmission risk. We also do not have data on whether patients were discharged to hospice bridge programs, which could impact readmission risk. Second, we lack information about patients’ coping strategies, social supports, baseline psychiatric disorders, cognition and delirium, and PTSD prior to their cancer diagnosis; such factors may affect the risk of PTSD symptoms among patients with cancer. Also, we used a PTSD screening instrument and do not have data on formal diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Third, we investigated associations among PTSD symptoms, symptom burden, and healthcare utilization in a sample with varying cancer types and stages, and thus we cannot comment on causality or determine the mechanisms of these associations. Finally, we obtained information about patients’ PTSD symptoms and their physical and psychological symptom burden within five days of hospital admission, but we lack information regarding changes in these symptoms over time. Future research should include longitudinal assessments to better understand how patients’ PTSD symptoms vary over time and in response to changes in other important factors, such as their physical and psychological symptom burden.

Our study provides innovative findings regarding the rates and correlates of PTSD symptoms among patients with cancer. In addition, by demonstrating associations between patients’ PTSD symptoms and greater physical and psychological symptom burden, we highlight the importance of addressing PTSD symptoms among this highly symptomatic population. Notably, the relationship we discovered between patients’ PTSD symptoms and lower risk of unplanned hospital readmissions underscores the need for investigators to study how PTSD symptoms may influence patients’ decision about when to pursue hospital-level care. Future research should focus on developing and testing interventions to address patients’ PTSD symptoms, in addition to their physical and psychological symptom burden, while empowering them to seek help appropriately and utilize healthcare services when needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: NCI K24 CA181253 (Temel), MGH Cancer Center Funds (Temel), Scullen Center for Cancer Data Analysis (Hochberg)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: No authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. All were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All provided final approval of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Submitted for the 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting in Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.Hirose T, Yamaoka T, Ohnishi T, et al. Patient willingness to undergo chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:483–489. doi: 10.1002/pon.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller LE. Sources of uncertainty in cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:431–440. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong ST, Butow PN, Tong A, et al. Patients’ experiences and perspectives of multiple concurrent symptoms in advanced cancer: a semi-structured interview study. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:1373–1386. doi: 10.1007/s00520-015-2913-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer SC, Kagee A, Coyne JC, DeMichele A. Experience of trauma, distress, and posttraumatic stress disorder among breast cancer patients. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:258–264. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116755.71033.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurevich M, Devins GM, Rodin GM. Stress response syndromes and cancer: conceptual and assessment issues. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:259–281. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldzweig G, Hasson-Ohayon I, Alon S, Shalit E. Perceived threat and depression among patients with cancer: the moderating role of health locus of control. Psychol Health Med. 2016;21:601–607. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1140902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gheihman G, Zimmermann C, Deckert A, et al. Depression and hopelessness in patients with acute leukemia: the psychological impact of an acute and life-threatening disorder. Psychooncology. 2016;25:979–989. doi: 10.1002/pon.3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan CMH, Ng CG, Taib NA, Wee LH, Krupat E, Meyer F. Course and predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder in a cohort of psychologically distressed patients with cancer: A 4-year follow-up study. Cancer. 2018;124:406–416. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koopman C, Butler LD, Classen C, et al. Traumatic stress symptoms among women with recently diagnosed primary breast cancer. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15:277–287. doi: 10.1023/A:1016295610660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cordova MJ, Andrykowski MA, Kenady DE, McGrath PC, Sloan DA, Redd WH. Frequency and correlates of posttraumatic-stress-disorder-like symptoms after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:981–986. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitman RK, Lanes DM, Williston SK, et al. Psychophysiologic assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder in breast cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:133–140. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegel MT, Moore CP, Collins ED, et al. Distress, psychiatric syndromes, and impairment of function in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:2924–2931. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SJ, Loberiza FR, Antin JH, et al. Routine screening for psychosocial distress following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:77–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Jawahri AR, Vandusen HB, Traeger LN, et al. Quality of life and mood predict posttraumatic stress disorder after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2016;122:806–812. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deimling GT, Kahana B, Bowman KF, Schaefer ML. Cancer survivorship and psychological distress in later life. Psychooncology. 2002;11:479–494. doi: 10.1002/pon.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Widows MR, Jacobsen PB, Fields KK. Relation of psychological vulnerability factors to posttraumatic stress disorder symptomatology in bone marrow transplant recipients. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:873–882. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200011000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holland JC, Reznik I. Pathways for psychosocial care of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;104:2624–2637. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brooks GA, Abrams TA, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Identification of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in patients with GI cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:496–503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouimette P, Wade M, Prins A, Schohn M. Identifying PTSD in primary care: comparison of the Primary Care-PTSD screen (PC-PTSD) and the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ) J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wachen JS, Patidar SM, Mulligan EA, Naik AD, Moye J. Cancer-related PTSD symptoms in a veteran sample: association with age, combat PTSD, and quality of life. Psychooncology. 2014;23:921–927. doi: 10.1002/pon.3494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry. 2003;9:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhondali W, Nguyen L, Palmer L, Kang DH, Hui D, Bruera E. Self-reported constipation in patients with advanced cancer: a preliminary report. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selby D, Cascella A, Gardiner K, et al. A single set of numerical cutpoints to define moderate and severe symptoms for the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hui D, Shamieh O, Paiva CE, et al. Minimal Clinically Important Difference in the Physical, Emotional, and Total Symptom Distress Scores of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuba K, Esser P, Scherwath A, et al. Cancer-and-treatment-specific distress and its impact on posttraumatic stress in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) Psychooncology. 2017;26:1164–1171. doi: 10.1002/pon.4295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manzano JM, Gadiraju S, Hiremath A, Lin HY, Farroni J, Halm J. Unplanned 30-Day Readmissions in a General Internal Medicine Hospitalist Service at a Comprehensive Cancer Center. J Oncol Pract. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.003087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:211–219. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306:1688–1698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmermann C, Burman D, Follwell M, et al. Predictors of symptom severity and response in patients with metastatic cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:175–181. doi: 10.1177/1049909109346307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stuber ML, Kazak AE, Meeske K, et al. Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms in childhood cancer survivors. Pediatrics. 1997;100:958–964. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamibeppu K, Murayama S, Ozono S, et al. Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Among Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Childhood Cancer: Importance of Monitoring Survivors’ Experiences of Family Functioning. J Fam Nurs. 2015;21:529–550. doi: 10.1177/1074840715606247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akechi T, Okuyama T, Sugawara Y, Nakano T, Shima Y, Uchitomi Y. Major depression, adjustment disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder in terminally ill cancer patients: associated and predictive factors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1957–1965. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cordova MJ, Studts JL, Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Andrykowski MA. Symptom structure of PTSD following breast cancer. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:301–319. doi: 10.1023/A:1007762812848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuoka Y, Nakano T, Inagaki M, et al. Cancer-related intrusive thoughts as an indicator of poor psychological adjustment at 3 or more years after breast surgery: a preliminary study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;76:117–124. doi: 10.1023/a:1020572505095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrill EF, Brewer NT, O’Neill SC, et al. The interaction of post-traumatic growth and post-traumatic stress symptoms in predicting depressive symptoms and quality of life. Psychooncology. 2008;17:948–953. doi: 10.1002/pon.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson AE, Morton RP, Broadbent E. Coping strategies predict post-traumatic stress in patients with head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:3385–3391. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-3960-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobsen PB, Widows MR, Hann DM, Andrykowski MA, Kronish LE, Fields KK. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after bone marrow transplantation for breast cancer. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:366–371. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199805000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rose JH, O’Toole EE, Einstadter D, Love TE, Shenko CA, Dawson NV. Patient age, well-being, perspectives, and care practices in the early treatment phase for late-stage cancer. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:960–968. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.9.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cassileth BR, Lusk EJ, Strouse TB, et al. Psychosocial status in chronic illness. A comparative analysis of six diagnostic groups. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:506–511. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408233110805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hurria A, Gupta S, Zauderer M, et al. Developing a cancer-specific geriatric assessment: a feasibility study. Cancer. 2005;104:1998–2005. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blank TO, Bellizzi KM. A gerontologic perspective on cancer and aging. Cancer. 2008;112:2569–2576. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Champion VL, Wagner LI, Monahan PO, et al. Comparison of younger and older breast cancer survivors and age-matched controls on specific and overall quality of life domains. Cancer. 2014;120:2237–2246. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, Bonevski B, Burton L, Cook P. The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Supportive Care Review Group. Cancer. 2000;88:226–237. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000101)88:1<226::aid-cncr30>3.3.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andrykowski MA, Cordova MJ. Factors associated with PTSD symptoms following treatment for breast cancer: test of the Andersen model. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11:189–203. doi: 10.1023/A:1024490718043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]