Abstract

MRSA is an increasing problem in humans as well as livestock. The bacterial co-colonization of the skin in MRSA carriers has been poorly investigated and moreover, there have been no methods for high resolution investigations of the Staphylococcus genus apart from tediously culturing or doing multiple PCRs. On 120 samples from pig ear, skin and nose, we generated amplicons from the V1-V2 region of the 16S rRNA gene to gather an overview of the genus-level microbiome, along with using MRSA specific plates to count MRSA. In parallel with this, amplicons of the tuf gene were generated, targeting only a region of the tuf gene found only in the Staphylococcus genus. Using these methods, we determined a core microbiota across the healthy pig and determined the Staphylococcus genus to be dominated by S. equorum. Moreover, we found Streptococcus to be inversely associated with Staphylococcus and MRSA, suggesting a role for this genus in combating MRSA. In this work, we have thoroughly investigated the skin and nose microbiome of the pig and developed a high throughput method for profiling the Staphylococcus genus which we believe will be useful for further investigations.

Introduction

During the last decade, a new strain of livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (LA-MRSA) has emerged worldwide in many different animal species e.g. cattle, poultry, mink, horses and especially pigs1–3. This strain, LA-MRSA CC398, is now widespread in Europe as well as in the Danish pig production4,5. At this point in time, the main issue of having LA-MRSA in production animals is the zoonotic risk it constitutes to farm workers6, although a spill-over to the general population may also occur4. It is unlikely that a complete elimination of LA-MRSA from the farm environment is possible without culling herds4, but an achievable ambition is perhaps to lower the level of LA-MRSA in farms. Previous studies have assessed the potential of possible interventions strategies, such implementation of disinfection and hygiene control measures7 or reduced usage of antimicrobials8, with inconclusive results. Radical measures have been implemented in the Norwegian pig production, which included a “search-and-destroy” policy, with depopulation and restocking of MRSA-free pigs. This method has shown to be effective in Norway, a country with low prevalence of MRSA in their pig production9, however impossible to implement in countries with high prevalence of LA-MRSA in pig farming such as Denmark10.

An alternative approach as intervention against LA-MRSA could be manipulation of the natural microbiome. It is known that the microbiome plays an important role in the health and disease of the host, and probiotics can in, the right amounts, confer considerable benefits to the host11,12. A study by13 found the human nasal microbiota not to be fixed by host genetics, and susceptible to environmental modifications. As concluded in the study, this perhaps allows for probiotics to be used in elimination of S. aureus nasal colonization or that a certain dermobiome selects for MRSA whereas another does not. A few animal studies have investigated the nasal microbiome in pigs. One study found a promising 20 bacterial candidates associated with non-carriage of S. aureus in the porcine nasal microbiome, including species from the family of Leuconostocaceae and Lachnospiraceae14. Another study found no significant difference in the microbiota of MRSA positive and negative pigs. However, they saw increased operational taxonomic units (OTUs) belonging to Firmicutes as main indicator of MRSA non-carriage, including Staphylococcus among others15. The approach used by Weese et al.15 did not allow for in depth resolution of the different staphylococcal species which, as pointed out by the authors, could be necessary to gain information regarding the potential protective effect against MRSA.

The use of the 16S rRNA gene is routinely used for profiling microbiotas due to its ubiquity and discriminatory power, but other genes, such as the Elongation Factor Thermo unstable (EF-Tu) gene (tuf), may be useful for more targeted investigations. This gene universally conserved in bacteria, and codes for a protein that binds tRNA in the cytoplasm and mediates entry into the ribosome16. It has previously been used to distinguish Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium17 as well as Staphylococcus18,19, but not yet in a high-throughput context.

In this study, we aimed to investigate the staphylococcal community in high resolution to identify which species dominate the pig nasal and skin microbiota and if any are associated with MRSA. As part of the instigation we have developed a high-throughput method based on selective primers targeting the tuf gene, e.g. an extension of the tuf-based classification used previously18,19. This enables one to achieve a large number of reads within the Staphyloccocus-genus, i.e. a large quantum of information, even at very low abundance. Swabs from clinical mink samples were included in the study as verification of the versatility of our approach. For cross-host verification, we included samples from both mink and pigs, as the major staphylococcal pathogens in mink are separate from the ones in pigs.

Results

The core microbiota of the skin, nose and ear

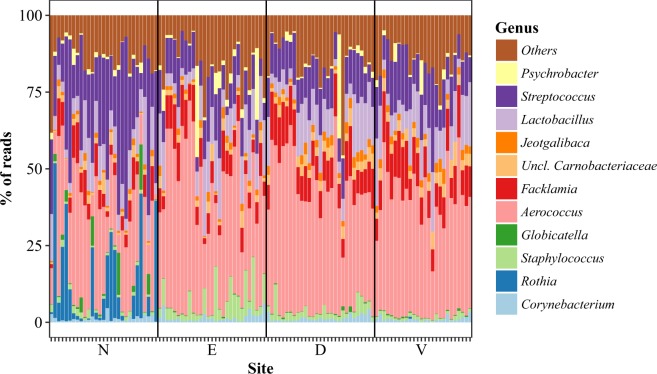

The overall microbiota was assayed by sequencing of the V1-V2-amplicons, which after the entire bioinformatics pipeline, contained 32,857 classified reads per sample on average. The samples were fairly similar across sites and were dominated by the genera Aerococcus (36.2%), Streptococcus (15.9%), Lactobacillus (10.4%), Facklamia (8.7%), Rothia (3.2%) and Staphylococcus (2.7%) forming a core microbiota (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Barplot of amplicons from 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Each column corresponds to a single sample in which the relative abundance of bacterial genera is shown through color coding. N: nose, E: ear, D: dorsal skin surface, V: ventral skin surface.

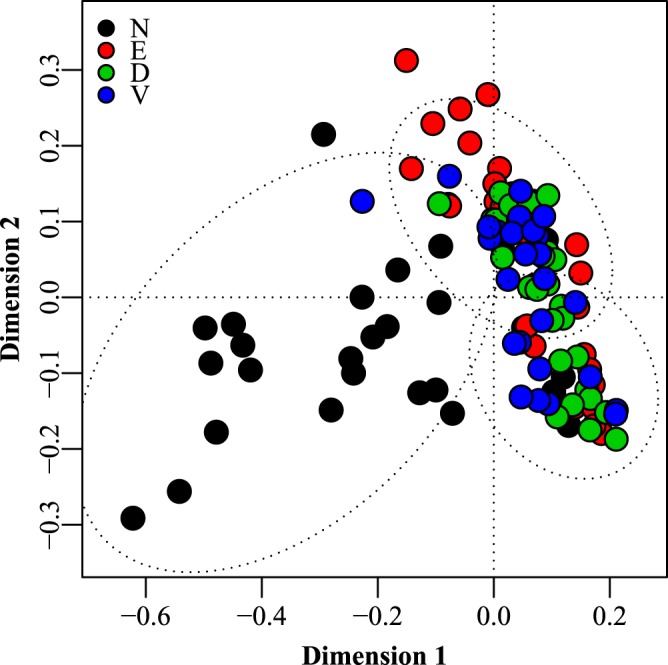

There were significant differences between sites according to multivariate analysis (P < 0.001 for ANOSIM, Adonis and PERMANOVA), as indicated in Figs 1 and 2. Pairwise comparisons using PERMANOVA showed that the ventral and dorsal surfaces were not significantly different, whereas the nose and the ear was significantly different from all other sites, the nose being the most dissimilar site (Figs 1 and 2). Canonical analysis of principal coordinates revealed that the genera separating the nose from the other sites were higher levels of Streptococcus, Rothia and Globicatella and lower levels of Aerococcus and Facklamia, whereas the ear was separated by higher levels of Staphylococcus and lower levels of Facklamia and Streptococcus.

Figure 2.

Principal coordinates analysis of amplicons from 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The multivariate ordination is based on the dissimilarity matrix derived from the relative abundance of bacterial genera across the samples. N: nose, E: ear, D: dorsal skin surface, V: ventral skin surface.

In univariate analysis, the nose uniquely harbored Rothia and had higher levels of Streptococcus and Moraxella, while levels of Aerococcus, Facklamia and Jeotgalibaca were lower (Fig. 3). The ears had the highest levels of Staphylococcus, but correspondingly lower levels of Streptococcus and Prevotella. The dorsal and ventral skin surface had higher levels of bacteria normally associated with the gut, such as Prevotella, Bacteroides and Enterococcus, although the dorsal surface was higher in Staphylococcus. The species within the Staphylococcus genus mapped almost exclusively to S. equorum or were unclassifiable beyond the genus level.

Figure 3.

The most abundant and otherwise interesting bacterial genera from 16S rRNA gene sequencing. N: nose, E: ear, D: dorsal skin surface, V: ventral skin surface. Differences are tested with Kruskal-Wallis and, if significant, different medians are denoted by different letters. P-values are adjusted for multiple comparisons.

The Shannon index, a measure of diversity, was not different across groups (P = 0.95). The Streptococcus genus was inversely correlated with Staphylococcus (pearsons ρ = −0.38, P < 0.001).

The Staphylococcus genus profiled by the tuf-gene

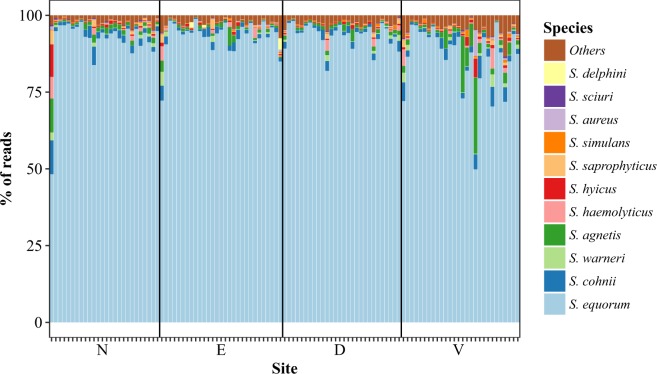

To gain a higher understanding of the species composition of the Staphylococcus genus in the samples, amplicons were generated from the tuf gene. The amplicons consisted exclusively of DNA classifiable to the Staphylococcus genus and primers were capable of amplifying the DNA of all tested species in the positive control, albeit with very different effectivity, e.g. S. equorum was positively biased and especially S. sciuri, S. haemolyticus and S. epidermidis was very negatively biased (See Supplementary Table S1). Using 16 S rRNA gene amplicons on the positive control did not find S. delphini, S. xylosus or S. sciuri and incorrectly found S. saprophyticus. 16S rRNA gene amplicons did however estimate more realistic proportions of the species herein, but when the Staphylococcus genus is a minority constituent, the species differentiation is low or non-existent.

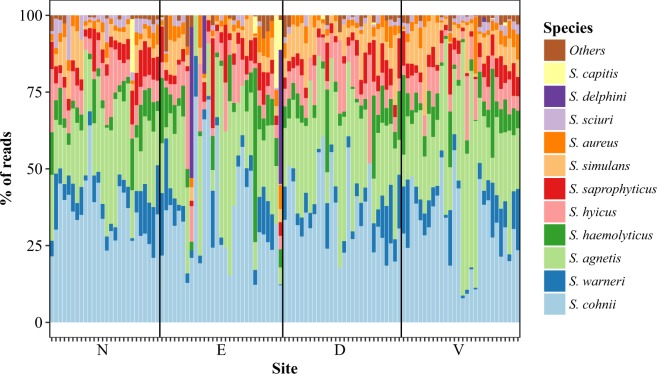

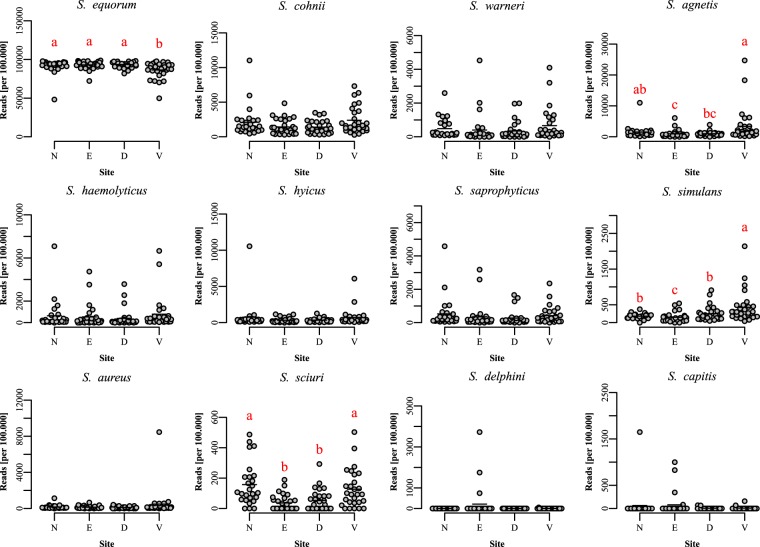

In the animal samples, 31,508 reads were available for classification per sample on average, and 95–99% of these reads were classifiable to an unambiguous single species using blastn. Several Staphylococcus species were found in all samples (Figs 4 and 5), but all were heavily dominated by S. equorum followed by varying proportions of most species included in the positive control. S. aureus was detected in all samples. Overall, the ear was the most dissimilar site (Fig. 6), as S. schleiferi, S. microti, S. simulans, S. hominis, S. lentus, S. sciuri and S. succinus were relatively lowered here. Moreover, the ventral skin surface was lower in S. equorum, and correspondingly higher in S. agnetis, S. simulans and S. sciuri. Using a qPCR targeting the S. equorum SodA gene, the presence of S. equorum was confirmed in all samples. There was a linear correlation between qPCR estimates of S. equorum (pearsons ρ = 0.35, P < 0.001), although several ear samples were poorly described by this relation. Omission of ear samples showed a substantially higher correlation (pearsons ρ = 0.75, P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

Composition of pig samples using tuf gene primers. Each column corresponds to a single sample in which the relative abundance of bacterial genera is shown through color coding. N: nose, E: ear, D: dorsal skin surface, V: ventral skin surface.

Figure 5.

Composition of pig samples using tuf gene primers with S. equorum subtracted. Each column corresponds to a single sample in which the relative abundance of bacterial genera is shown through color coding. N: nose, E: ear, D: dorsal skin surface, V: ventral skin surface.

Figure 6.

The most abundant and otherwise interesting staphylococcal species from tuf sequencing. N: nose, E: ear, D: dorsal skin surface, V: ventral skin surface. Differences are tested with Kruskal-Wallis and, if significant, different medians are denoted by different letters. P-values are adjusted for multiple comparisons.

MRSA levels on pig and mink

The presence of MRSA was assayed using MRSA selective plates. MRSA was present in all samples with levels around 103 cfu/sample in ear and skin swab samples, whereas slightly lower levels, generally between 102 and 103 cfu/sample were recorded in nasal swab samples (Fig. 7A). MRSA plate counts was negatively correlated with Streptococcus (pearsons ρ = −0.42, P < 0.001) (Fig. 7B), but poorly related to total Staphylococcus, possibly reflecting that most of the staphylococci are S. equorom. We did not find any large correlations (pearsons ρ > 0.2) between the bacteria found using the tuf-primers and MRSA counts.

Figure 7.

(A) MRSA counts by plating and the association to Streptococcus by V1-V2 sequencing. (B) Correlations of Streptococcus and MRSA CFU. N: nose, E: ear, D: dorsal skin surface, V: ventral skin surface. Differences are tested with Kruskal-Wallis and, if significant, different medians are denoted by different letters.

For mink, included for cross-validation of the used methods, the V1-V2 primers showed a diverse group of bacterial families, including Staphylococcus. The staphylococci in these V1-V2 samples were not classifiable at a species level or classified mainly as S. pseudintermedius. The tuf primers generated amplicons in most of the samples, mainly classified as S. delphini which is in agreement with classification by MALDI-TOF (data not shown). S. delphini was not detected using V1-V2 primers.

Discussion

In this set of data, the microbiota of the nose, the outer ear and two sites of the skin were investigated using three different methods in order to investigate associations between the microbiota, MRSA and individual species of the Staphylococcus genus.

The overall skin and nasal microbiota was rich in Aerococcus, Staphylococcus, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Facklamia and Rothia (nose only), which is in some contrast to previous studies where bacteria belonging to the phylum Proteobacteria have dominated. One paper found a high abundance of the phylum Proteobacteria (including Moraxella, Psychrobacter and Pseudomonas) in the nose, whereas the present results are much higher in Firmicutes. The authors also found negative associations with MRSA for Lactobacillus and Staphylococcus, and proposed a more thorough investigation using specific primers15. A study looking at the tonsil microbiota of pigs also found high levels of Proteobacteria, especially Pasteurella, and an overall composition substantially different than in the present data, possibly explained by the different body site investigated20. A more recent paper reported high nasal levels of Gammaproteobacteria, mainly mapped to the genus Moraxella, which we also found abundantly in the nose. Compared to the present data, the paper also found similar levels of Lactobacillus and Staphylococcus21. Moraxella is well known as an inhabitant of mucosal surfaces22, and consequently, its dominance in nasal samples is not unexpected. Swe et al.23 investigated the microbiota of the ear thoroughly and found high levels of Streptococcus, Lactobacillus and Corynebacterium, but less Aerococcus and in contrast to our results, Rothia was found in the ear. Rothia nasimurium is a gram positive coccoid bacterium that was first described from the nose of healthy mice24, but it is found frequently in nasal swab samples from healthy pigs in our lab. It grows on MRSA2 agar with colonies similar to MRSA and thus constitutes a differential diagnostic issue. Regarding the dorsal and ventral skin of the animal, this has been investigated recently in a study by McIntyre et al.25, where high levels of Firmicutes, including Ruminocococeae, Lachnospiraceae, Streptococcus and Prevotellaceae were found and similar compositions were seen in the ventral and dorsal sites. Espinosa-Gongora et al.14 specifically investigated the nasal microbiota of MRSA carrier pigs vs. non-carriers, and apart from a core microbiota dominated by Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, species within Lachnospiraceae and Leuconostoc were shown to be differentially abundant in these animals. A differential analysis of carriers vs. non-carriers could not be carried out in the present data, as all animals were positive for MRSA in agreement with estimates of MRSA prevalence in Danish pigs10. The inverse relation of Streptococcus to MRSA and Staphylococcus observed in our data has previously been reported in Bessesen et al.26 where a significant negative relation between Streptococcus mitis and MRSA was found in human samples through 16S rRNA gene sequencing and confirmed with in vitro inhibition assays. In future work, individual strains of Streptococcus from the samples of interest should be isolated and assayed for possible antagonistic effects towards MRSA.

MRSA specific plates were used to enumerate MRSA as there currently is no reliable molecular technique to quantify MRSA in mixed samples. The use of plates unfortunately is sensitive to the load of bacteria in the samples, which may explain why MRSA loads were lower in the nose.

We sought to further elucidate the composition of the staphylococcal genera by the use of primers specific for the tuf gene, an approach already considered for Staphylococcus by previous papers18,19. The primers used by Martineu et al.18 were chosen for a metataxonomic approach as their product length was better suited for the 2 × 250bp MiSeq platform. The primers were entirely specific for staphylococci and were successful in amplifying all species tested, albeit with differing specificity. In contrast to non-specific primers, such as for the 16 S rRNA gene, the tuf primers will selectively amplify and provide resolution in samples very low in staphylococci, even to the degree where these are undetectable by 16S rRNA gene primers. The use of tuf primers also allows detection S. delphini as in mink. The primers cannot, though, distinguish between MRSA or methicillin sensitive S. aureus, as these differentiated by the presence of a mecA cassette and not a variation in the tuf gene. Inspection of the tuf gene of the negatively biased species revealed various levels of mismatch in the primers, e.g. 2 out of 5 sequences classified as S. haemolyticus in the database generated from NCBI had a single mismatch in both the forward and reverse primer. On the other hand, all 5 sequences classified as S. saphrolyticus were perfectly matched by both primers, although these were biased against in the sequencing. The reasons for the positive bias of S. equorum are less clear, as the region of the primer binding site of other negatively biased species such as S. cohnii or unbiased species such as S. aureus were identical to those in S. equorum. Ideally, the primers would amplify all staphylococcal species equally, which will require further development. Alternative tuf primers or use of the SodA gene as in Blaiotta et al.27 should be investigated. Further degeneration of the primers could be beneficial to encompass all species, although it is doubtful if all bias can be completely removed. The issue of different sequences classified as the same species (e.g. as for S. haemolyticus) further complicates intelligent primers design.

In the pigs, we observed very high levels of S. equorum, a species first found on the skin of healthy horses28 and described in the nose of pigs29, followed by S. schleiferi, S. cohnii and S. microti, as well as S. aureus in all samples, whereas the mink samples were dominated by S. delphini. The high prevalence of S. equorum, a species hitherto not having received much attention, was further investigated with a specific qPCR, showing that all samples were positive for S. equorum and that the relative abundance estimated from sequencing was in agreement with the relative abundance estimated by qPCR.

In conclusion, we have conducted a thorough investigation of the skin, nose and ear microbiota of the pig and implemented a high resolution method for elucidation of the Staphylococcus genus. The use of tuf-specific primers, despite not being entirely quantitative, allows for detection of individual Staphylococcus-species even in very low abundance, making future investigation of staphycoccal populations more straightforward.

We found that the microbiota of the nose differed significantly from the microbiota at the skin sites. The microbiome in all sites was dominated by Aerococcus, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Facklamia, Rothia and Staphylococcus, whereas the nose was enriched with Streptococcus and Moraxella and uniquely harboring Rothia. The staphylococcal population was heavily dominated by S. equorum followed by S. schleiferi, S. cohnii and S. microti, as well as S. aureus. In the nose, the level of MRSA was negatively correlated with the level of Streptococcus which makes Streptococcus a possible target of interest regarding manipulation of the natural microbiota towards an anti-MRSA environment.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

Pig samples were obtained at a commercial slaughterhouse (Danish Crown, Ringsted, Denmark), immediately following controlled atmosphere stunning by CO2 but prior to euthanasia. Each animal (n = 30) was sampled behind one ear, in the nose and on the ventral and dorsal skin surface by use of individual ESwabs (Copan Diagnostics Inc., Murrieta, CA, USA) for a total of 120 samples. The ear was sampled by three gliding motions behind the pinna, the nose by a rotary motion ~1 cm inside each of the nares and on the two skin surfaces by three consecutive ~3 cm strokes in the same location. All handling of animals was in accordance with regulations from the Danish Ministry of Justice.

Mink samples, some positive and some negative for MRSA were acquired from routine diagnostics of clinical mink sent to DTU-VET. Swab samples from throat were obtained as described by Hansen et al.2.

A Staphylococcus control was made by a mixing cultures of S. aureus (both resistant and sensitive to methicillin), S. cohnii, S. delphini, S. equorum, S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus, S. hyicus, S. schleiferi, S. sciuri, S. succinus, and S. xylosus equally, which subsequently was subjected to the same purification, PCR-amplification and sequencing procedure as the pig and mink samples.

MRSA enumeration by culturing

Samples were processed within 2 hours of sampling and were not centrifuged or filtered due to concerns regarding flocculation of staphylococci and/or adhesion to skin cells and dust particles. For direct quantification of MRSA, 100 µL sample material, undiluted and in 10−1 dilution, was plated on MRSA-selective plates (Brilliance MRSA2 agar, Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK). Plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight and suspected MRSA colonies were counted after 18–24 h. One colony from each positive sample was confirmed as MRSA by MALDI-TOF and PCR detection of the mecA and nuc genes30.

Microbiota analysis and preparations

DNA from each sample was purified with a Maxwell® LEV Blood DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). First, the swab was vigorously shaken at high speed to loosen the cells from the swab. The whole sample was then transferred to a 2 ml Eppendorf tube and centrifuged for 15 min at 20.000 g. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was incubated for 60 min at 37 °C with 100 µl of lysozyme mixture (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 2 mM EDTA, 1.2% Triton X, 200 µg/ml lysostaphin and 25 mg/ml lysozyme). Subsequently, the samples were mixed with 350 µl lysis buffer, and one 5 mm stainless steel bead (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) was added to the samples followed by shaking on a Qiagen TissueLyser II (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) for 2 min at 20 Hz. Samples were then incubated for 1 h at 56 °C with 30 µl proteinase K, 20 mg/ml. The DNA was then extracted on a Maxwell®16 Research Instrument System (Promega Corporation, Wisconsin, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of the DNA was quantified on a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Negative controls were included for purification to control background contamination.

The V1-V2 regions of 16 S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR and sequenced as described by Strube et al.31 using primers V1V2Fw: 5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′ and V1V2Rv: 5′-CTG CTG CCT YCC GTA-3′ tagged with hexameric barcodes and PCR conditions including 94 °C for 6 min; 30 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 57 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 90 s; and 72 °C for 10 min. The tuf gene amplicons were prepared using primers adapted from Martineau et al.18, TufFw: 5′-GGC CGT GTT GAA CGT GGT CAA ATC A-3′ and TufRv: 5′-TIA CCA TTT CAG TAC CTT CTG GTA A-3′, but were tagged with unique hexameric barcodes to allow for multiplexing of samples. The PCR program included 94 °C for 5 min and 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 45 s, 72 °C for 90 s, and 72 °C for 10 min (final extension). The negative controls from the DNA purification, were included in both PCRs. Specificity of the primers were tested by PCR on pure culture of Rothia nasimurium, Corynebacterium sp., Clostridium perfringens, Propionibacterium acnes, Streptococcus suis, Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus casei, all of which were negative. The resulting PCR products for both primer sets, included negative controls, were then analyzed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using an AgilentDNA1000 kit (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) and further pooled in equimolar ratios (50 ng per barcoded sample). The pooled DNA was then purified of primers and detergents using a Qiagen MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Amplicons were submitted to The National High-Throughput DNA Sequencing Centre at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, for sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq 250PE platform. The V1-V2 amplicons were then merged, quality filtered, chimera-checked and mapped against the RDP-II SSU database using the BION-meta software (Danish Genome Institute, Aarhus, Denmark). The tuf gene amplicons were merged and quality filtered using BION-meta, clustered at 97% similarity with USEARCH32, de-novo chimera checked with UCHIME33 and taxonomically assigned using the blastn algorithm from command line BLAST with a custom made tuf database, using a word length of 22 and a minimum similarity of 90%. An alternative workflow using only USEARCH was also investigated, but was abandoned due to lower sensitivity. The tuf database was built by downloading all Staphylococcus genomes being either classified as “Complete genome” or “Scaffold” from NCBI Genbank (as indexed in ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/genbank/bacteria/assembly_summary.txt) followed by extraction of all CDS annotated as tuf genes using an in-house Perl- and bash-based script (available upon request). The tuf genes were then checked for correct length (between 1150 bp and 1200 bp) and used as a database for blastn. The tuf gene from S. delphini was added manually.

An S. equorum specific qPCR targeting the S. equorum sodA gene was carried out as described in Blaiotta et al.27 with the addition of QuantiTect SYBR Green (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) using 25 ng DNA for each reaction. A standard curve of serial dilutions of S. equorum DNA was used to ensure amplification efficiency. The estimates of S. equorum from the qPCR, expressed in S. equorum DNA per 25 ng total DNA, was compared to the estimates of total Staphylococcus from 16S rRNA sequencing to further investigate the levels of S. equorum.

Statistical analysis

All samples were normalized to 100,000 reads before further analysis and data is presented in its entirety when plotted. To avoid issues of normality, individual OTUs were compared using Kruskal-Wallis followed by Conover-Iman test if significant as implemented in the agricolae package34. The Shannon-index was used to estimate diversity and was tested with ANOVA. Multivariate patterns were visualized by principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) and tested for groupwise differences with ANOSIM, Adonis and PERMANOVA from the vegan package35, all using Bray-Curtis distances. Canonical analysis of principal coordinates was used to evaluate bacteria of interest. Correlations are calculated and plotted as log10 using Pearson correlations. P-values below 0.05 were considered significant, and were adjusted for multiple comparisons using Sidak-corrections36 when doing multiple univariate analyses. All tests were two-tailed.

Ethics Approval and Consent To Participate

All handling of animals was in accordance with regulations from the Danish Ministry of Justice.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Ms. Margrethe Carlsen for assistance with the mink samples. The work in this paper has been supported by a grant from The Danish Agrifish Agency (grant no. 33010-NIFA-14-612).

Author Contributions

M.L.S., J.E.H. and K.P. conceived the idea, M.L.S. and J.E.H. collected the samples and wrote the manuscript, S.O.P.R. and J.E.H. performed the laboratory work, S.O.P.R. validated the primers, M.L.S. performed the bioinformatics and data analysis. All authors interpreted the data and read and approved the manuscript.

Availability of Data

All sequence files, de-multiplexed, merged and quality-filtered, are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) as part of the Bioproject found at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA399517. Metadata is given in supplementary file 1.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-30689-y.

References

- 1.Petinaki E, Spiliopoulou I. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among companion and food-chain animals: impact of human contacts. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:626–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen JE, et al. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is widespread in farmed mink (Neovison vison) Vet. Microbiol. 2017;207:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuny C, et al. Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in different animal species. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010;300:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone, K. Risk Assessment on Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), with a focus on Livestock-Associated MRSA, in the UK Food Chain. Food Standards Agency (2017).

- 5.DANMAP. Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, food and humans in Denmark. ISSN 1600-2032 (2015).

- 6.Köck R, et al. The impact of zoonotic MRSA colonization and infection in Germany. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2014;127:384–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espinosa-Gongora C, Panduro P, Saxmose S. Effect of a disinfectant powder on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in pigs, bedding and air samples under simulated farm conditions. Pig J. 2013;68:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorado-García A, Graveland H, Bos MEH, Verstappen KM. Van Cleef BAGL, Kluytmans JAJW, et al. Effects of reducing antimicrobial use and applying a cleaning and disinfection program in veal calf farming: experiences from an intervention study to control livestock-associated MRSA. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grøntvedt CA, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC398 in humans and pigs in Norway: a “One Health” perspective on introduction and transmission. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63:1431–1438. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Environment and Food of Denmark. MRSA Risiko og håndtering Rapport ved MRSA-ekspertgruppen. http://mfvm.dk/fileadmin/user_upload/MFVM/MRSA_rapport.pdf (2017).

- 11.Ouwehand AC, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Probiotics: an overview of beneficial effects. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2002;82:279–289. doi: 10.1023/A:1020620607611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho JH, Zhao PY, Kim IH. Probiotics as a dietary additive for pigs: A review. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2011;10:2127–2134. doi: 10.3923/javaa.2011.2127.2134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu CM, et al. Staphylococcus aureus and the ecology of the nasal microbiome. Sci. Adv. 2015;1:e1400216–e1400216. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1400216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espinosa-Gongora C, Larsen N, Schønning K, Fredholm M, Guardabassi L. Differential analysis of the nasal microbiome of pig carriers or non-carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weese JS, Slifierz M, Jalali M, Friendship R. Evaluation of the nasal microbiota in slaughter-age pigs and the impact on nasal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carriage. BMC Vet. Res. 2014;10:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lathe WC, Bork P. Evolution of tuf genes: Ancient duplication, differential loss and gene conversion. FEBS Lett. 2001;502:113–116. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02639-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ventura M, Canchaya C, Klaenhammer TR, Zink R. Analysis, characterization, and loci of the tuf genes in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species and their direct application for species identification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:6908–6922. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.11.6908-6922.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martineau F, et al. Development of a PCR assay for identification of staphylococci at genus and species levels. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001;39:2541–2547. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2541-2547.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang SM, Kim MS, Park KU, Song J, Kim EC. tuf gene sequence analysis has greater discriminatory power than 16S rRNA sequence analysis in identification of clinical isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:4142–4149. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05213-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe BA, et al. Defining the “core microbiome” of the microbial communities in the tonsils of healthy pigs. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slifierz, M. J., Friendship, R. M. & Weese, J. S. Longitudinal study of the early-life fecal and nasal microbiotas of the domestic pig. BMC Microbiol. 15(184) 1–12 8 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Quinn, P. J. et al. Veterinary Microbiology and Microbial Disease, 2nd Edition. (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

- 23.Swe PM, Zakrzewski M, Kelly A, Krause L, Fischer K. Scabies mites alter the skin microbiome and promote growth of opportunistic pathogens in a porcine model. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8:11–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins MD, Hutson RA, Båverud V, Falsen E. Characterization of a Rothia-like organism from a mouse: Description of Rothia nasimurium sp. nov. and reclassification of Stomatococcus mucilaginosus as Rothia mucilaginosa comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000;50:1247–1251. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-3-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McIntyre MK, Peacock TJ, Akers KS, Burmeister DM. Initial characterization of the pig skin bacteriome and its effect on in vitro models of wound healing. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bessesen MT, et al. MRSA colonization and the nasal microbiome in adults at high risk of colonization and infection. J. Infect. 2015;71:649–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blaiotta G, Ercolini D, Mauriello G, Salzano G, Villani F. Rapid and reliable identification of Staphylococcus equorum by a species-specific PCR assay targeting the sodA gene. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2004;27:696–702. doi: 10.1078/0723202042369901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schleifer KH, Kilpper-Bälz R, Devriese LA. Staphylococcus arlettae sp. nov., S. equorum sp. nov. and S. k1oosii sp. nov.: Three new coagulase-negative, novobiocin-resistant species from animals. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1984;5:501–509. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(84)80007-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tulinski P, et al. Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci on pig farms as a reservoir of heterogeneous staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:299–304. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05594-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maes N, Magdalena J, Rottiers S, De Gheldre Y, Struelens MJ. Evaluation of a triplex PCR assay to discriminate Staphylococcus aureus from coagulase-negative staphylococci and determine methicillin resistance from blood cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002;40:1514–1517. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.4.1514-1517.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strube ML, Ravn HC, Ingerslev H-C, Meyer AS, Boye M. In situ prebiotics for weaning piglets: in vitro production and fermentation of potato galacto-rhamnogalacturonan. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:1668–1678. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03582-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Mendiburu, F. agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/package=agricolae (2016).

- 35.Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan (2016).

- 36.Šidák Z. Rectangular confidence regions for the means of multivariate normal distributions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1967;62:626–633. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All sequence files, de-multiplexed, merged and quality-filtered, are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) as part of the Bioproject found at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA399517. Metadata is given in supplementary file 1.