Abstract

Innate immunity can induce spontaneous hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance (SC) of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection or transition towards an inactive carrier state. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 3 signalling has been linked to these processes. Alterations in the TLR3 gene might impair immune responses against HBV. In our study, we analysed the impact of the TLR3 polymorphisms rs3775291 and rs5743305 on the natural course of HBV infection. In this retrospective study, a Caucasian cohort of 621 patients with chronic HBV infection (CHB), 239 individuals with spontaneous HBsAg SC, and 254 healthy controls were enrolled. In the CHB group, 49% of patients were inactive carriers, and 17% were HBeAg-positive. The TLR3 rs3775291 A allele was associated with a reduced likelihood of spontaneous HBsAg SC and HBeAg SC, and an increased risk of developing chronic hepatitis B. In haplotype analysis, the haplotype including both risk variants rs3775291A and rs5743305A had the lowest likelihood of HBsAg SC. Further research in larger cohorts and functional analyses are needed to shed light on the impact of TLR3 signalling.

Introduction

The risk of developing chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and its complications correlate with the disease stage, which reflects the degree of immune control. Thus, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occur more often in the active phase of the disease, but their prevalence is reduced if hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion, inactive carrier (IC) state and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss occurs1. The mechanisms underlying this immune control over the HBV infection have not been fully explained. It is, however, known that adaptive immune responses are required to resolve the infection, especially HBV specific T cells2,3. In contrast, the role of innate immunity in the control of HBV infections remains controversial. Recent studies showed the effect of Toll-like receptors (TLR) on HBV infection by initiating antiviral responses and stimulating adaptive immune responses4–6. Furthermore, TLR-mediated immune responses are shown to inhibit HBV replication in hepatocytes and animal models7–9. Interactions between TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, TLR7 and TLR9 and HBV have been reported previously5,6,10.

TLR3 detects double-stranded (ds) RNA from viruses, endogenous dsRNA and synthetic polyinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid (poly I:C). TLR3 signalling leads to activation of transcription factors such as interferon-regulatory factor-3 (IRF3) and nuclear factor (NF)-кB and induces the production of interferon-β and inflammatory cytokines11. The receptor is expressed in hepatocytes as well as in macrophages, natural killer (NK) cells and biliary epithelial cells, and is located in the plasma membrane or acidic endosomes5. Macrophages and NK cells are essential for immune recognition and virus eradication in innate and early adaptive immune responses against HBV12,13. Furthermore, TLR3 can activate hepatic non-parenchymal cells (NPCs) such as Kupffer cells, liver sinusoidal endothelial cells to produce interferon-β during HBV infection8.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the TLR3 gene may cause changes in the protein or gene expression, which affects the function and efficacy of signal transduction and thus an altered immune response. In previous reports, TLR3 polymorphisms rs1879026, rs3775296, rs3775291, rs5743305 have been associated with the outcome of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HBV infection, and the development of consequential liver cirrhosis and HCC primarily in Asian populations14. Similarly, Al-Qahtani et al. showed a significant effect of the haplotype GCGA, composed of the four SNPs rs1879026, rs5743313, rs5743314, and rs5743315, on the susceptibility of HBV infection in persons from Saudi Arabia15. Huang et al. also identified the SNP rs3775290 as a protective factor against the development of chronic HBV infection and advanced stages of liver disease in the Chinese population16. Thus, evidence suggests that a link exists between TLR3 variants and immune control over HBV infections but to date, a clear association in a large Caucasian patient population is lacking.

This study investigates the presence of the TLR3 SNPs rs3775291 and rs5743305 in a large multicentre cohort of patients with HBV infection and healthy controls of Caucasian ethnicity. We selected these SNPs as they have recently been found to represent new risk factors of HBV-related diseases in an Asian population14 and affect TLR3 signalling17–19. We aimed to assess the impact of these SNPs on the susceptibility of chronic HBV infection (CHB), spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance (SC) and the occurrence of different disease stages of CHB such as HBeAg SC and inactive carrier (IC) state.

Results

Patient characteristics

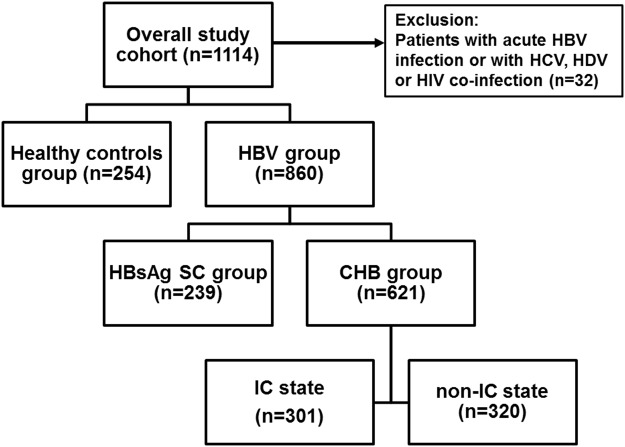

The subdivision of the overall study cohort is presented in Fig. 1. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort (n = 1114) are shown in Table 1. Individuals in the CHB group were significantly younger (Man-Whitney U = 4830.5, p = 1.29 × 10−22) and included more females (χ2 = 4.72 p = 0.03) as compared to the group of patients with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance (HBsAg SC) group. The HBsAg SC group had significantly more patients with liver cirrhosis (χ2 = 4.94 p = 0.031) and elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) levels (Mann-Whitney U = 52578.5, p = 0.002) than the CHB group. However, cirrhosis development and elevated ALT levels in the HBsAg SC patients was primarily caused by excessive alcohol consumption (44%), followed by idiopathic (32%) causes, autoimmune (12%) and non-alcoholic liver diseases (12%).

Figure 1.

Overview of the investigated study population. The overall study population included healthy controls and the HBV group. Patients with acute HBV infection or HCV, HDV or HIV co-infection were excluded from the study. Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) was characterized by the presence of HBsAg and HBV DNA for more than six months and spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance (HBsAg SC) was defined by undetectable HBsAg and detectability of anti-HBs and total anti-HBc antibodies. The CHB group was further divided into an inactive carrier (IC) state and in a non-IC state according to the current European guidelines1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the (a) overall HBV cohort and the control group and (b) the CHB patients in inactive carrier (IC) state or non-IC.

| Parameter | (a) HBV cohort | Control | (b) CHB | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg SC (n = 239) | CHB (n = 621) | P-value | Controls (n = 254) | P-value† | IC state (n = 301) | non-IC state (n = 320) | P-value | HBeAg + (n = 103) | HBeAg- (n = 518) | P-value | |

| Age (years)* | 64.9 ± 14.3 | 53.6 ± 13.9 | 1.29 × 10−22 | 63.5 ± 2.8 | 3.10 × 10−28 | 52.4 ± 13.5 | 54.7 ± 14.3 | 0.088 | 53.4 ± 14.2 | 53.6 ± 13.8 | 0.675 |

| Male gender | 128 (53.6%) | 383 (61.7%) | 0.03 | 45 (17.7%) | 5.62 × 10−34 | 164 (54.5%) | 219 (68.4%) | 0.0004 | 79 (76.7%) | 304 (58.7%) | 0.001 |

| Inactive carriers | n.a. | 301 (48.5%) | n.a. | 4 (3.9%)** | 297 (57.3%) | 3.89 × 1026 | |||||

| HBeAg-positive | n.a. | 103 (16.6%) | n.a. | 4 (1.3%)** | 99 (30.9%) | 4.17 × 10−27 | |||||

| Cirrhosis | 50 (20.9%) | 92 (14.8%) | 0.031 | n.a. | 28 (9.3%) | 63 (19.7%) | 0.0003 | 22 (21.4%) | 69 (13.3%) | 0.046 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 9 (3.8%) | 41 (6.6%) | 0.142 | n.a. | 10 (3.3%) | 31 (9.7%) | 0.002 | 8 (7.8%) | 33 (6.5%) | 0.663 | |

| Previous or current antiviral treatment | n.a. | 352 (56.7%) | n.a. | 87 (28.9%) | 264 (82.5%) | 2.76 × 10−43 | 99 (96.1%) | 252 (48.5%) | 7.77 × 10−20 | ||

| HBV DNA (log10 IU/ml)* | n.a. | 3.4 ± 2.4* | n.a. | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 2.5 | 2.15 × 10−47 | 6.04 ± 2.22 | 2.85 ± 2.04 | 7.15 × 1029 | ||

| ALT (IU/L)* | 69.3 ± 327.15 | 61.6 ± 140.1* | 0.0002 | n.a. | 31.8 ± 23.3 | 89.9 ± 190.3 | 7.53 × 10−19 | 85.32 ± 107.4 | 56.95 ± 145.2 | 1.47 × 10−9 | |

†p-value from the comparison of the CHB group with the controls, CHB: chronic hepatitis B, SC: seroclearance, *mean ± SD, n.a. not applicable. **HBeAg loss during observation time.

Comparisons of continuous variables were made using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared with the Pearson’s χ2 test.

In the CHB group, more females developed an IC state (χ2 = 12.77 p = 0.0004) than males. And within the non-IC group, there were significantly more patients with liver cirrhosis (χ2 = 13.38 p = 0.0003) and fewer patients with HCC (χ2 = 10.19 p = 0.002). Moreover, baseline HBV DNA (Mann-Whitney U = 14864.0, p = 2.15 × 10−47) and ALT levels (Mann-Whitney U = 27722.5, p = 7.53 × 10−19) were significantly lower in the IC group.

Prevalence of TLR3 SNPs in individuals with and without HBV infection

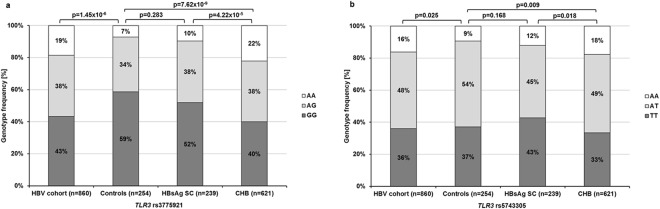

The genotype distributions of both TLR3 SNPs rs3775291 and rs5743305 differed significantly between the healthy controls and the HBV cohort (Fig. 2). The A allele of rs3775291 (χ2 = 18.69 p = 1.69 × 10−5) and the AA genotype of rs5743305 (χ2 = 7.08 p = 0.008) were overrepresented in the HBV cohort.

Figure 2.

Genotype distributions of the TLR3 SNPs rs3775291 (a) and rs5743305 (b) in the overall cohort and in the sub-groups. Frequencies were compared with Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables. The genotype distribution of both SNPs differed significantly between the study cohort and healthy controls and between the CHB and HBsAg SC groups (HBsAg: hepatitis B surface antigen, SC: seroclearance and CHB: chronic hepatitis B).

When the HBV cohort was further divided into the HBsAg SC and CHB group, the differences in TLR3 SNPs genotype distribution only remained significant between the controls and the CHB group (Fig. 2). Thus, univariate logistic regression analysis revealed a higher likelihood of CHB for the TLR3 rs3775291 A allele (odds ratio [OR] = 2.13 [95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.59–2.87] p = 5.60 × 10−7) and the rs5743305 AA genotype (OR = 2.06 [95% CI: 1.29–3.30] p = 0.002). In adjusted multivariate logistic regression analysis, both SNPs remained significantly associated with CHB (rs3775291A: OR = 2.45 [95% CI: 1.69–3.48] p = 1.65 × 10−6 and rs5743305A: OR = 3.031 [95% CI: 1.74–5.29] p = 9.55 × 10−6). Furthermore, age-matched analysis revealed an increase in power regarding the association of the risk variants with CHB (rs3775291A: OR = 3.26 [95%CI: 1.96–5.42] p = 5.18 × 10−6 and rs5743305A: OR = 3.59 [95% CI: 1.80–7.18] p = 0.0003).

Association of TLR3 SNPs with spontaneous HBsAg SC of HBV infections

Genotype distributions of both TLR3 SNPs differed significantly between the HBsAg SC and the CHB groups (Fig. 2). In univariate logistic regression analysis, the rs3775291 AA genotype was associated with a reduced likelihood of spontaneous HBsAg SC with an OR of 0.38 (95% CI: 0.24–0.60, p = 4.54 × 10−5) under a recessive model and the A allele (risk variant) with an OR of 0.62 (95% CI: 0.46–0.83, p = 0.002) under a dominant model; the TLR3 rs5743305 A allele (risk variant) was associated with an OR of 0.67 (95% CI: 0.50–0.91, p = 0.011) under a dominant model, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Genotype distribution of the TLR3 SNPs and the association with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance (SC) using logistic regression analysis.

| TLR3 | CHB (n = 621) | HBsAg SC (n = 239) | Unadjusted OR (CI 95%) | P-value | Adjusted OR (CI 95%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3775291 | GG | 248 (39.1%) | 124 (51.9%) | ||||

| AG | 236 (38.0%) | 92 (38.5%) | |||||

| AA | 137 (22.1%) | 23 (9.6%) | |||||

| MAF | 0.41 | 0.29 | |||||

| AA/AG vs. GG | 0.62 [0.46–0.83] | 0.002 | 0.58 [0.42–0.80] | 0.001 | |||

| AA vs. AG/GG | 0.38 [0.24–0.60] | 4.54 × 10−5 | |||||

| rs5743305 | TT | 207 (33.3%) | 102 (42.7%) | ||||

| AT | 304 (49.0%) | 108 (45.2%) | |||||

| AA | 110 (17.7%) | 29 (12.1%) | |||||

| MAF | 0.42 | 0.35 | |||||

| AA/AT vs. TT | 0.67 [0.50–0.91] | 0.011 | 0.66 [0.48–0.93] | 0.016 | |||

| AA vs. AT/TT | 0.64 [0.41–0.99] | 0.048 | |||||

CHB: chronic hepatitis B, SC: seroclearance, OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval.

Since age, gender and patient origin are important risk factors for the development of chronic HBV infection, we performed adjusted multivariate logistic regression analysis and confirmed the strength of the association of both risk variants of TLR3 rs3775291 (OR = 0.58 [95% CI: 0.42–0.80] p = 0.001) and rs5743305 (OR = 0.66 [95% CI: 0.48–0.93] p = 0.016) with HBsAg SC (Table 2). An increase in power was detected using age-matched groups (rs3775291A: OR = 0.47 [95%CI: 0.30–0.72] p = 0.001 and rs5743305A: OR = 0.55 [95% CI: 0.35–0.86] p = 0.008).

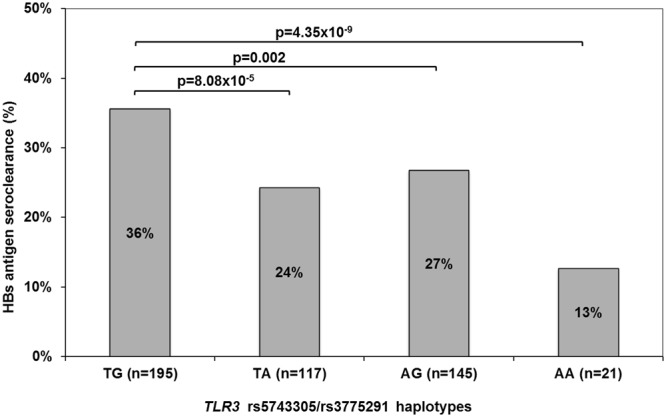

Haplotype analysis of TLR3 rs5743305 and rs3775291

In our cohort, the TLR3 SNPs rs5743305 and rs3775291 are in weak linkage disequilibrium (LD) (D’ = 0.058, r2 = 0.001). Therefore, four haplotypes exist: rs5743305T/rs3775921G (36.4%), rs5743305T/rs3775921A (25.9%), rs5743305A/rs3775921G (23.4%) and rs5743305A/rs3775921A (14.2%). Carriers of at least one A allele of the TLR3 SNPs had lower chances of HBsAg SC than carriers of the wild-type genotypes, for example, 24% TA vs. 37% TG χ2 = 15.54 p = 8.08 × 10−5 (Fig. 3). The lowest likelihood of HBsAg SC was assessed for the AA haplotype comprising both risk variants with an OR of 0.26 (95% CI: 0.16–0.43, p = 8.51 × 10−8) compared to the TG haplotype (Table 3).

Figure 3.

HBsAg seroclearance rates of the TLR3 rs5743305/rs3775291 haplotypes.

Table 3.

Haplotypes of TLR3 rs5743305/rs3775291 associated with spontaneous HBsAg seroclearance in the study cohort using logistic regression analysis.

| TL3 rs5743305/rs3775291 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Haplotype | Frequency | OR [95% CI] | p-value |

| TG | 0.364 | REF | |

| TA | 0.259 | 0.58 [0.44–0.76] | 8.75 × 10−5 |

| AG | 0.234 | 0.66 [0.51–0.86] | 0.002 |

| AA | 0.142 | 0.26 [0.16–0.43] | 8.51 × 10−8 |

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, REF = reference.

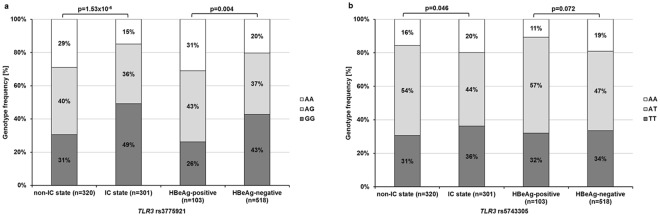

Association of the TLR3 SNPs with hepatitis B disease stages

We examined the association of both TLR3 SNPs with the disease stages of chronic HBV infection, specified through the following analyses: 1) HBV DNA levels, 2) ALT levels; 3) the IC state vs. non-IC state; 4) HBeAg-negative vs. HBeAg-positive CHB; and the presence or absence of 5) cirrhosis and 6) HCC across the CHB cohort.

Patients carrying the TLR3 rs3775291 or rs5743305 risk variants had higher HBV DNA and ALT levels than carriers of the GG or TT genotype (rs3775291: HBV DNA log10 IU/mL: p = 8.55 × 10−8 and ALT IU/mL: p = 0.001; rs5743305: p = 0.006 and p = 0.017, respectively) using Mann-Whitney U test.

The genotype distribution of TLR3 rs3775291 was significantly different between all groups, and the distribution of rs5743305 only between the IC and non-IC groups, respectively (Fig. 4). Univariate logistic regression analysis revealed a significant association of the TLR3 rs3775291 risk variant with a higher likelihood of development of active chronic hepatitis B (OR = 2.13 [95% CI: 1.54–2.95] p = 6.00 × 10−6) and with HBeAg positivity (OR = 2.10 [95% CI: 1.31–3.36] p = 0.002). By using Bonferroni correction, the rs3775291 risk variant remained significantly associated with non-IC, with an OR of 2.16 (95% CI: 1.55–3.01, p = 5.50 × 10−6) and HBeAg presence, with an OR of 2.06 (95% CI: 1.28–3.33, p = 0.003). For both SNPs, there was neither an association with the presence of cirrhosis nor the development of HCC.

Figure 4.

Genotype distributions of the TLR3 SNPs rs3775291 (a) and rs5743305 (b) in the CHB group. Frequencies were compared with Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables. The genotype distributions of both SNPs significantly differed between patients with non-IC and IC states. Only the SNP rs3775291 was significantly different between HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients. IC: inactive carrier.

Discussion

In this large multicentre Caucasian population study, we showed for the first time a strong association of the common SNP rs3775291 in the TLR3 gene with different stages of immune control over chronic HBV infections and with spontaneous HBsAg SC.

To date, the functional relevance of SNPs in the TLR3 gene is not entirely known. The substitution of G to A at position rs3775291 leads to an amino acid change from leucine to phenylalanine at position 412 of the protein. This alteration reduces the localisation of the soluble ectodomain and the dimerization of TLR3 at membranes, resulting in its decreased binding capacity to dsRNA and a lower signalling activity compared to the wild-type17,18. The polymorphism rs5743305 is located in the promotor region of the TLR3 gene and is suggested to influence transcriptional activity. However, Askar and colleagues detected no impaired TLR3 gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PMBCs) of heterozygous or homozygous rs5743305 variants compared to wild-type19. Although their effect on transcriptional activity is not completely clear, both SNPs are shown to be associated with low humoral and cellular response to measles vaccination. For example, the heterozygous variants of both SNPs were associated with lower levels of measles-specific antibodies (wild-type vs. variant: rs3775291 p = 0.02, rs5743305 p = 0.004), and the heterozygous variant of rs5743305 showed a lower lymphoproliferative response compared to the wild-type (p = 0.003)20.

In our study, the risk variants of rs3775291 and rs5743305 were more prevalent in CHB group compared to healthy controls (Fig. 2), a difference that may have been influenced by a lower risk exposure of the control group. However, those patients who achieved spontaneous HBsAg SC showed a similar distribution of the risk variants as controls. Interestingly, the difference between the HBsAg SC and the CHB groups was similar to the difference between the CHB group and control, suggesting an influence of both risk variants on the immune control of HBV infections.

Another marker of immune control over HBV infections is the occurrence of HBeAg SC. In our study, the incidence of the GG genotype of TLR3 rs3775291 was higher in patients who had achieved HBeAg SC in comparison to HBeAg-positive patients. The AA genotype was more frequent in HBeAg-positive patients, which further supports an association of the rs3775291 variants with an altered innate immune response during HBV infection. Similar to the rs3775291 SNP, the risk variant of rs5743305 was also associated with disease stages in CHB. However, the associations were not independent of the rs3775291 SNP, suggesting a possible relationship between both TLR3 polymorphisms.

Because haplotypes are considered to be more informative than single-locus analyses with regard to associations with complex diseases21, we performed haplotype analyses for TLR3 rs3775291 and rs5743305. We detected an additive effect of both SNPs. The presence of at least one risk allele reduced the likelihood of HBsAg SC rates by ~40% compared to wild-type, and the presence of two risk alleles up to 75%, respectively.

Our observation regarding the association of TLR3 risk variants with HBsAg SC contradicts findings of previous studies16,22–24. Sa et al. observed no difference of both SNPs between chronically infected patients (n = 35) and healthy subjects (n = 299) from Brazil23. In Asian population, HBV is mainly passed by perinatal transmission, whereas HBV in Caucasians is primarily adult-acquired by exposure to infected blood and various body fluids25. Therefore, both rates of HBsAg SC and epidemiology of CHB differ between the populations. Nevertheless, this study and other previous reports show a link between TLR3 SNPs and HBV susceptibility16,23,24, and our study is the first to show an association of the risk variants of rs3775291 and rs5743305 with decreased HBsAg SC in Caucasian patients.

Other TLR3 variants that have not been analysed in our study may also play a role in the immune control of HBV infection. Interestingly, Goktas et al.26 reported that in Turkish patients with active CHB there was a higher prevalence of the CC genotype of the TLR3 SNP rs3775290, which is located close to rs3775291. They suggest that the wild-type might lead to a stronger immune response against HBV. Conversely, in our study, the TLR3 rs3775291 risk variant presented higher baseline HBV DNA and ALT levels as well as an association with active CHB. This might be due to the impaired functional activity of TLR3 with subsequent decreased HBV recognition and increased HBV propagation in the liver.

We were unable to detect any association between TLR3 risk variants and liver cirrhosis or HCC, which is contrary to findings by Li et al.27 and Chen et al.22 in Asian patients. Their studies suggest that the TLR3 SNP rs3775291 is a novel risk factor for HBV-related HCC. The lack of an association with HCC might be due to the limited number of patients with advanced liver disease or HCC in our cohort, or the different ethnic background. Therefore, further investigations are needed in large cohorts of patients with HBV-related HCC.

One limitation of our study is the yet unproven functional relevance of TLR3 in HBV infections. Although HBV is known to be a “stealth” virus which does not trigger an interferon response in infected hepatocytes28–30, innate immunity of liver-resident macrophages, Kupffer cells and NPCs can be activated4,8,31,32. The HBV replication phase with increased production, assembly and release of HBV particles from hepatocytes results is a higher local exposure to these immune cells30. Future studies need to confirm if TLR3 signalling can be activated by the internalisation of the immature RNA-containing virions, which are being secreted during HBV production33, or if other mechanisms are involved. However, recent investigations show that stimulation of TLRs with exogenous ligands improves immune responses against HBV5,7–9,34–37, and can induce the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in chronically infected HBV patients36. Furthermore, TLR agonists also activate cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses and inhibit HBV propagation7–9,37. Triggering of TLR-mediated pathways will become critical in approaching host factor-targeted treatment strategies to cure HBV infection35,38. Thus, polymorphism in genes of key components of the TLR-signalling pathways might also affect individual therapy outcome.

In conclusion, the current study shows for the first time that the TLR3 gene GG genotype of the SNPs rs3775291 and the TT genotype of rs5743305 are associated with HBsAg SC and IC state, and the GG genotype of rs3775291 is linked to HBeAg SC in Caucasians. Thus, TLR3 may represent an important factor in immune control over HBV infection. Nonetheless, large population-based studies in HBV populations with different genetic backgrounds, as well as testing for additional TLR3 variants and functional analyses, are needed to understand the effect of genetic variations in the complex mechanisms on immune control during the different phases of HBV infection.

Patients and Methods

Patients

A total of 1114 patients with HBV infection and healthy controls of Caucasian origin from two academic hepatology centres in Germany (Section of Hepatology, University Hospital of Leipzig, Germany and Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, University Hospital Charité, Berlin, Germany) and one primary health provider (Liver and Study Center Checkpoint, Berlin, Germany) were enrolled onto the study between 2003 and 2015. Patients with acute HBV infection or HCV, HDV or HIV co-infection were excluded from the study.

The overall study population included: a control group of 254 unrelated healthy blood donors (all with undetectable HBsAg and total anti-HBc antibodies) and 860 patients in the HBV group, which included the CHB group (n = 621) with the presence of HBsAg and HBV DNA for more than six months, and the HBsAg SC group (n = 239 patients) with spontaneous HBsAg SC, defined by undetectable HBsAg and detectability of anti-HBs and total anti-HBc antibodies. The patients in the CHB group were further divided into those in an IC state (n = 301, HBeAg-negative and HBV DNA levels <2,000 IU/mL, persistently normal serum ALT levels) and those with non-IC state (n = 320, HBV DNA level >2,000 IU/mL or elevated serum ALT levels in the absence of secondary liver disease), according to the current European guidelines1 (Fig. 1). Caucasian was defined as patients descended from Northern/Central or Eastern Europe (n = 859), the Mediterranean region (Turkey, Greece or Italy, n = 229) or the Middle East (Iran, Afghanistan, n = 26).

Since HBV infection often presents entirely asymptomatic during the acute phase, and the infection goes unrecognised in a large proportion of affected patients39, the age at first infection and the route of transmission were not available for numerous patients, especially for those who spontaneously cleared the virus. Moreover, the chronic patients were from academic liver centres, and selection bias cannot be excluded.

Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed by radiological evidence and/or a liver biopsy. The diagnosis of HCC was based on histological examination of tumour tissue or evidence on imaging40.

Genotyping

The DNA samples were analysed from whole blood samples stored at −20 °C for the TLR3 SNPs rs3775291 and rs5743305. DNA was extracted from whole blood samples with an extraction kit from QIAGEN (Hilden, Germany). Genotyping was performed by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and melting curve analysis in a Light Cycler 480 System (Roche) using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) probes (TIB MOLBIOL, Berlin, Germany). PCR conditions and primer/probes sequences are shown in the Supplementary Material. Sequencing was performed with BigDye Terminator and a capillary sequencer from Applied Biosystems (Darmstadt, Germany).

Statistics

Statistical analyses of epidemiological associations were performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., version 24.0, Chicago, IL, USA). The genotype distributions of the two SNPs were tested for deviations from the HWE41 using the DeFinetti program with a cut-off p-value of 0.01.

Comparisons of the distributions of demographical characteristics between the different groups were made using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables (each when adequate) and the Pearson’s χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the association between the SNPs and the disease status under dominant and recessive genetic models.

All tests were two-sided and p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The OR and the 95% CI were calculated. We aimed to estimate both the recessive and additive effects of the SNPs. Structure of LD was analysed with Haploview 4.2 (Broad Institute, Cambridge, USA) by using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm. The LD present between the single SNPs. D’ varies from 0 (complete equilibrium) to 1 (complete disequilibrium). R2 shows the correlation between SNPs. When r2 = 1, two SNPs are in perfect LD, and allelic frequencies are identical for both SNPs41.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Medical Research of the University of Leipzig and Berlin in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from 1975 (revision 2013) and the International Conference on Harmonization/Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products “Good Clinical Practice” guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Peter Bugert, Medical School of Mannheim, for providing the blood samples of the persons included in the healthy control group, further thanks to the technical staff and patients involved in this study. We would like to thank Laura A. Kehoe, Medical Communications, for proofreading and editing. This study was supported by a research grant of GILEAD Sciences GmbH.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the acquisition of data, review and critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. J.F.: overall coordination of the study, study design, experiments and procedures, interpretation of data, manuscript writing; E.K.: study design/conception, experiments and procedures, interpretation of data; F.v.B. and T.B.: study design/conception, interpretation of data, R.H., F.B. and E.S.: sample and data provision.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the public repository of the University Leipzig under, http://ul.qucosa.de/.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-31065-6.

References

- 1.EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology. 2017;67:370–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer T, Sprinzl M, Protzer U. Immune Control of Hepatitis B Virus. Dig Dis. 2011;29:423–433. doi: 10.1159/000329809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isogawa M, Tanaka Y. Immunobiology of hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology Research: The Official Journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology. 2015;45:179–189. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busca A, Kumar A. Innate immune responses in hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Virology Journal. 2014;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Z, Zhang E, Yang D, Lu M. Contribution of Toll-like receptors to the control of hepatitis B virus infection by initiating antiviral innate responses and promoting specific adaptive immune responses. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2015;12:273–282. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nosratabadi R, Alavian SM, Zare-Bidaki M, Shahrokhi VM, Arababadi MK. Innate immunity related pathogen recognition receptors and chronic hepatitis B infection. Molecular Immunology. 2017;90:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luangsay S, et al. Early inhibition of hepatocyte innate responses by hepatitis B virus. Journal of Hepatology. 2015;63:1314–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu J, et al. Toll-like receptor-mediated control of HBV replication by nonparenchymal liver cells in mice. Hepatology. 2007;46:1769–1778. doi: 10.1002/hep.21897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isogawa M, Robek MD, Furuichi Y, Chisari FV. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Inhibits Hepatitis B Virus Replication In Vivo. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:7269–7272. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.7269-7272.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kataki K, et al. Association of mRNA expression of toll-like receptor 2 and 3 with hepatitis B viral load in chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Med. Virol. 2017;89:1008–1014. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vercammen E, Staal J, Beyaert R. Sensing of Viral Infection and Activation of Innate Immunity by Toll-Like Receptor 3. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2008;21:13–25. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00022-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura K, Kakimi K, Wieland S, Guidotti LG, Chisari FV. Activated Intrahepatic Antigen-Presenting Cells Inhibit Hepatitis B Virus Replication in the Liver of Transgenic Mice. J. Immunol. 2002;169:5188. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knolle PA, Gerken G. Local control of the immune response in the liver. Immunological Reviews. 2000;174:21–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geng P-L, et al. Toll-Like Receptor 3 is Associated With the Risk of HCV Infection and HBV-Related Diseases. Medicine. 2015;95:e2302. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Qahtani A, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 polymorphism and its association with hepatitis B virus infection in Saudi Arabian patients. Journal of Medical Virology. 2012;84:1353–1359. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang X, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in Toll-like receptor 3 gene are associated with the risk of hepatitis B virus-related liver diseases in a Chinese population. Gene. 2015;569:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou P, Fan L, Yu K-D, Zhao M-W, Li X-X. Toll-like receptor 3 C1234T may protect against geographic atrophy through decreased dsRNA binding capacity. The FASEB Journal. 2011;25:3489–3495. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-189258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranjith-Kumar CT, et al. Effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms on Toll-like Receptor 3 Activity and Expression in Cultured Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:17696–17705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Askar E, et al. TLR3 gene polymorphisms and liver disease manifestations in chronic hepatitis C. J. Med. Virol. 2009;81:1204–1211. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhiman N, et al. Associations between SNPs in toll-like receptors and related intracellular signaling molecules and immune responses to measles vaccine: Preliminary results. Vaccine. 2008;26:1731–1736. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, N., Zhang, K. & Zhao, H. In Haplotype‐Association Analysis, pp. 335–405 (Academic Press 2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Chen D, et al. Gene polymorphisms of TLR2 and TLR3 in HBV clearance and HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese male population. The International Journal of Biological Markers. 2017;32:e195–e201. doi: 10.5301/jbm.5000238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sa KSD, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 gene polymorphisms are not associated with the risk of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2015;48:136–142. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0008-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rong Y, et al. Association of Toll-like Receptor 3 Polymorphisms with Chronic Hepatitis B and Hepatitis B-Related Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. Inflammation. 2013;36:413–418. doi: 10.1007/s10753-012-9560-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Croagh CMN, Lubel JS. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: Phases in a complex relationship. World Journal of Gastroenterology: WJG. 2014;20:10395–10404. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goktas EF, et al. Investigation of 1377C/T polymorphism of the Toll-like receptor 3 among patients with chronic hepatitis B. Can. J. Microbiol. 2016;62:617–622. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2016-0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li G, Zheng Z. Toll-like receptor 3 genetic variants and susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma and HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumor Biology. 2013;34:1589–1594. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0689-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ait-Goughoulte M, Lucifora J, Zoulim F, Durantel D. Innate antiviral immune responses to hepatitis B virus. Viruses. 2010;2:1394–1410. doi: 10.3390/v2071394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lebossé F, et al. Intrahepatic innate immune response pathways are downregulated in untreated chronic hepatitis B. Journal of Hepatology. 2017;66:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng X, et al. Hepatitis B virus evades innate immunity of hepatocytes but activates cytokine production by macrophages. Hepatology. 2017;66:1779–1793. doi: 10.1002/hep.29348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boltjes A, Movita D, Boonstra A, Woltman AM. The role of Kupffer cells in hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. Journal of Hepatology. 2014;61:660–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heydtmann M. Macrophages in Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Virus Infections. Journal of Virology. 2009;83:2796–2802. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00996-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu J, Liu K, Protzer U, Nassal M. Complete and Incomplete Hepatitis B Virus Particles: Formation, Function, and Application. Viruses. 2017;9:56. doi: 10.3390/v9030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suslov A, Boldanova T, Wang X, Wieland S, Heim MH. Hepatitis B Virus Does Not Interfere With Innate Immune Responses in the Human Liver. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1778–1790. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lucifora J, et al. Direct antiviral properties of TLR ligands against HBV replication in immune-competent hepatocytes. Scientific Reports. 2018;8:5390. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23525-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tjwa ETTL, et al. Restoration of TLR3-Activated Myeloid Dendritic Cell Activity Leads to Improved Natural Killer Cell Function in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Journal of Virology. 2012;86:4102–4109. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07000-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwarz K, et al. Role of Toll-like receptors in costimulating cytotoxic T cell responses. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33:1465–1470. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bertoletti A, Rivino L. Hepatitis B: future curative strategies. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2014;27:528–534. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang TJ. Hepatitis B: The Virus and Disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2009;49:S13–S21. doi: 10.1002/hep.22881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.European Association for the Study of the Liver & European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. EASL–EORTC Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology56, 908–943 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Weir BS. Linkage Disequilibrium and Association Mapping. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2008;9:129–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the public repository of the University Leipzig under, http://ul.qucosa.de/.